By Steve Roth, the Publisher of Evonomics. He is a Seattle-based serial entrepreneur, and a student of economics and evolution. He blogs at Asymptosis, Angry Bear, and Seeking Alpha. Twitter: @asymptosis. Originally published at Evonomics

You hear a lot about bottom-up and middle-out economics these days, as antidotes to a half-century of “trickle-down” theorizing and rhetoric. You’re even hearing it, prominently, from Joe Biden.

They’re compelling ideas: put more wealth and income in the hands of millions, or hundreds of millions, and you’ll see more economic activity, more prosperity, and more widespread prosperity. To its proponents, it seems deeply intuitive or even obvious, a formula for The American Dream.

But curiously, you don’t find much nuts and bolts economic theory supporting that view of how economies work. There’s been lots of research on the sources and causes of wealth and income concentration. There’s been a lot of important work on the social and political effects of inequality — separate (though tightly related) issues. But unlike the steady stream of “incentive” theory from Right economists over decades, Left and heterodox economists have largely failed to ask or answer a rather basic theoretical (and empirical) question: what are the purely economic effects of highly-concentrated wealth, held by fewer people, families, and dynasties, in larger and larger fortunes?

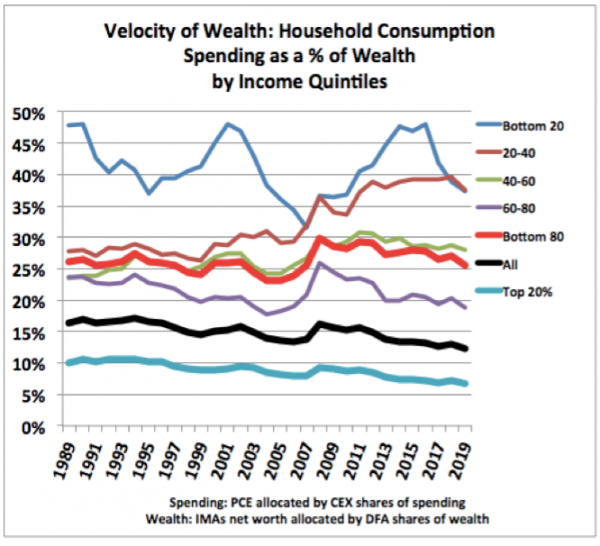

In a new paper and model published in Real-World Economics Review, I try to tackle that question. The model takes advantage of national accountants’ wealth measures that have only been available since 2006 or 2012 (with coverage back to 1960), and measures of wealth distribution that were only published in 2019. Combined with thirty+ years of consistent survey data on consumer spending at different income levels, the paper derives a novel economic measure: velocity of wealth.

The bottom 80% group turns over its wealth in annual spending three or four times as fast as the top 20%. The arithmetic takeaway: at a given level of wealth, more broadly distributed wealth means more spending: the very stuff of economic activity, which is itself the ultimate source of wealth accumulation.

The details of the model are somewhat more complex, but it only employs five easy to understand formulas — all basically just arithmetic, and all expressed without resort to abstruse symbols; they use plain language.

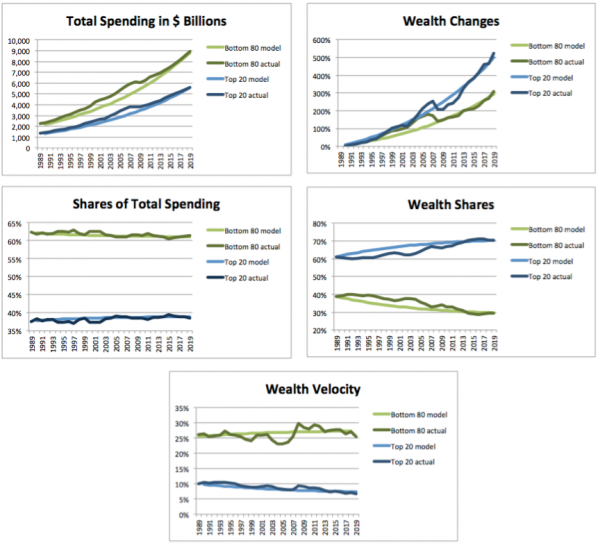

How good are the model’s predictions? It starts with just two numbers in 1989 — the wealth of the top 20% and the bottom 80% — and extrapolates forward using those few formulas to predict levels of wealth, spending, and shares of wealth and spending, thirty years later.

Compare the model’s predictions for 2019 to actual results; in each case they’re almost identical.

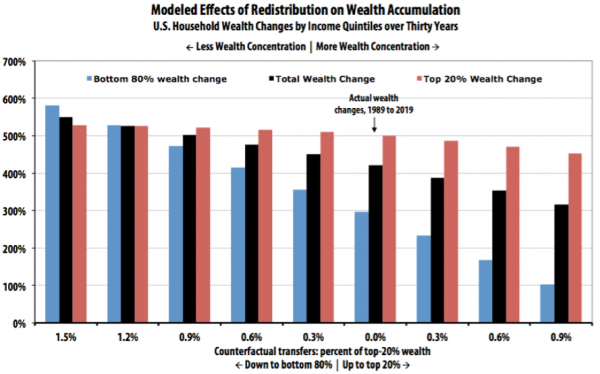

It’s easy to add counterfactuals to this model: what would have happened if some percentage of top-20% wealth was transferred, redistributed, to the bottom 80% every year over those three decades. The results are pretty eye-popping.

Downward redistribution appears to make everyone quite a lot wealthier, faster – especially (no surprise) the bottom 80%. Economic activity, annual spending, increases even faster. Taking the leftmost bars as an example: with an annual 1.5% downward transfer, greater spending would have resulted in a 549% total wealth increase, versus actual 421%. (To put that 1.5% downward transfer in context: the compounding annual growth rate on a passive wealthholder’s 60/40 stock/bond portfolio over that thirty years was about 7.5%. That’s all unearned income, received simply for holding wealth.)

Most of that extra wealth growth would have gone to the bottom 80% (wealth growth of 527% vs actual 295%), while top-20% wealth growth would also have been slightly higher than actual (526% vs 499%). The top-20% share of wealth would have remained unchanged, versus the actual share increase, from 61% to 71%.

With 1.5% in downward redistribution, 2019’s total consumption spending — a pretty good index or proxy for GDP — would have been 52% higher. Total wealth would have been 16% higher.

It’s worth noting: excepting the two leftmost scenarios (1.5% and 1.2%), the top 20% keep getting relatively richer than the bottom 80%. Avoiding the increased wealth concentration that we’ve seen since 1989 (or even reducing the 1989 concentration) would have required at least an annual 1.2–1.5% downward wealth transfer from the top 20%.

The very richest percentile groups, of course, might not have gotten richer with downward redistribution. It would depend on the mechanics and progressivity of the transfers. The data available here don’t let us determine that using this model. But the transfers would have to be far larger than envisioned here before top-percentile wealth levels (vs their relative share) actually stagnated or declined. Absent quite extreme redistribution, the rich keep getting richer as the economy grows. But with adequate redistribution to counter the ever-present trend toward economy-crippling wealth concentration, everybody else prospers as well.

The paper, model, data, and all calculations are available here.

The wealthy and even the not-wealthy seem to resist this kind of thinking. Their principles of lack and finite resources tell them that they can only achieve wealth by paying out as little as possible to the working class, and keeping them “hungry.” A large “disposable” population has kept the wealthy from having to adjust their thinking. Now that people have had time to think during lockdowns, and fertility is down, is this the only way this will change? People aren’t “agreeing” on a large enough scale lately, will they be starved into submission? When will the concepts of “enough” and “sharing” support distribution of wealth? (I am not expecting anyone to answer me). Economics models never seem to take into account the human behavior aspects.

I wouldn’t ascribe this to the bosses’ “principles of lack and finite resources” so much as to their desire for dominance. As to “economic models” a Kalecki quote that Yves has cited comes to mind:

The maintenance of full employment would cause social and political changes which would give a new impetus to the opposition of the business leaders. Indeed, under a regime of permanent full employment, the “sack” would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow. Strikes for wage increases and improvements in conditions of work would create political tension.

by “principles of lack and finite resources” I meant these are enforced upon us by “the bosses” as the means to get and maintain dominance. this model above shows the fallacy, which will just be mental gymnastics, not anything that will be considered to be put into practice, for the reasons you give in your second paragraph.

Thank you, GramSci, I was trying to remember the Kalecki quote because it agrees with my experience.

The emotional need to dominate is very powerful indeed and it is relative status and wealth that matter to those with this particular insecurity ( Madness?).

Interesting paper and you’re right, you don’t see this laid out so plainly.

I wonder if it’s possible to extrapolate what current distributions will look like in 20 years using past 20 years of data.

@Cocomaan: “I wonder if it’s possible to extrapolate what current distributions will look like in 20 years using past 20 years of data.”

Check out the little table, “Projections extrapolated…” Redistribution appears to have little effect on future wealth concentration. Seems to suggest that we’re at or near something like a natural limit, where the concentration itself makes it progressively harder to achieve further concentration.

This is one of the most bigoted and factually false comments I have ever read. Warren Buffett and Bill Gates LOVE fast food hamburgers and eat them all the time. Buffett also eats his breakfast every day at McDonald’s. Zuck eats McDonald’s burgers too. So are they “retarded”?

The reason low income people eat fast food (which is not necessarily junk food; chains increasingly offer healthier stuff along with the traditional fatty/high carb stuff; some fast food chains like Zoes offer only healthy food) is that all in it often costs no more than a prepared meal. And they are typically time stressed and also often live in food deserts.

Take your ignorant prejudice elsewhere.

I run into Bill Gates twice. One on a large SW conference, and one in a Wellington, New Zealand, Starbucks. He looked out of place there, not because “Bill” was at Starbucks, but because few Kiwis (at least then) went to Starbucks in CBD wearing a tracksuit with their wife (who wasn’t in a tracksuit).

It looks like this comment got moved from its correct location. Clearly it’s a response to another comment … was the original removed?

It looks like Jules removed it without seeing that I had replied.

Here it is:

This looks like Hicks’ version of Keynes.

The Marginal Propensity to Consume has been trotted out in every recession since the 1930s.

Poor people spend more of each additional dollar of income than do the rich.

Therefore, transfers from rich to poor will boost aggregate consumption.

The limiting factor is inflation. If transfers cause demand to exceed supply, the price level rises.

Raising the minimum wage would have accomplished this outcome.

Too bad this wasn’t done when Mr. Biden had the opportunity to do it.

before the election….

2000 checks, 50,000 student loan break, wait 10,000, we have to be realistic here…and 15min wage!

Vote for biden he’s going to do some things for you!

After the election

1400 checks…from trump…student loans, huh? Let me look at my notes..um, no, don’t see anything there, next question…15/hr min wage? Inflation ACK!!! They can’t even raise the min wage to 8/hr.

I’m not sure raising the minimum wage is a particularly effective way of redistributing income. I think that it does some good, but there are reasons for doubt, like to my understanding the CBO estimates that the minimum wage hike recently discussed would lift a million people out of poverty but eliminate 1.5 million jobs IIRC. That may be a good deal, I don’t know, and it may be a pessimistic estimate, it seems that way to me and many economists, I think. But it places the burden for helping minimum wage employees (which isn’t necessarily a great proxy for poverty) on people who employ minimum wage workers (which isn’t a great proxy for wealth). I think that most minimum wage workers work in restaurants and brick and mortar retail, neither of which seem very well positioned to bear huge burdens at the moment. Although both would benefit from the additional demand, so it’s hard to say. Carbon Tax funding a UBI would in my opinion elegantly redistribute wealth from polluters(which is a pretty good proxy for wealth, for example Bill Gates private jet was estimated to have burned 1500 tons of fuel in one year and would count his share of Microsofts emissions) to everyone whether they earned minimum wage or not so helping kids and the un/underemployed and disabled as well.

so there are 1.5 million jobs that greedy capitalists are unnecessarily paying for? Say it ain’t so!

If they are jobs that need to be done what happens then?

This kind of “thinking” is little more than hearsay, a repetition of the same tired and phony hand-wringing about how you can’t pay people a living wage or we’d have no jobs. On its face this notion is nonsense. History bears this out. When Seattle approved a $15/hour minimum in wage — by *referendum* — one of the scare tactics from opponents was the Job-Killing Boogeyman. Restaurants will close, business will tank, food servers will be unemployed and the situation will actually worsen, they said.

After the law took effect, the exact opposite happened. The restaurant business *boomed*. Why is that? Because suddenly all those people had more disposable income, and so they started going out to eat more.

@Rob Urie:

If you read the paper you’ll see that while “marginal propensity” does indeed factor large, it’s marginal propensity relative to wealth (velocity), not income. The latter construct actually explains why econs don’t think distribution matters (much). (See the Bernanke quote.) It really can’t, because “saving rate” can’t/doesn’t change much, or actually have the effects that econs vaguely imagine.

“Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities…”

By contrast: “The large, persistent observed differences in wealth velocity across the wealth/income distribution provide one straightforwardly transparent mechanism to explain such effects.”

Keynesian economics was bad.

I remember that.

Neoclassical economics was bad.

No one could remember that.

“That’s handy Harry!” the globalists

The globalists found just the economics they were looking for.

The USP of neoclassical economics – It concentrates wealth.

Let’s use it for globalisation.

Mariner Eccles, FED chair 1934 – 48, observed what the capital accumulation of neoclassical economics did to the US economy in the 1920s.

“a giant suction pump had by 1929 to 1930 drawn into a few hands an increasing proportion of currently produced wealth. This served then as capital accumulations. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied themselves the kind of effective demand for their products which would justify reinvestment of the capital accumulation in new plants. In consequence as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When the credit ran out, the game stopped”

This is what it’s supposed to be like.

A few people have all the money and everyone else gets by on debt.

This is why Keynes added redistribution to the system.

It stopped all the wealth concentrating at the top and gave rise to a strong healthy middle class.

Neoclassical economics was bad.

No one could remember that.

In the 1930s, the Americans found margin lending and share buybacks had artificially inflated the markets and this had lead to the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

What lifted US stocks to 1929 levels in 1929?

Margin lending and share buybacks.

What lifted US stocks to 1929 levels in 2019?

Margin lending and share buybacks.

A former US congressman has been looking at the data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zu3SgXx3q4

We relied on price signals from markets, but forgot what had been discovered in the 1930s after last time.

The markets can be artificially inflated, by things like margin lending and share buybacks.

Now we’ve got a ponzi scheme of inflated asset priced prices that could come crashing down, just like last time.

Oh yeah, I remember now.

It’s all coming back to me.

Being an idiot, I listened to a fair bit of that youtube thing. So, “Peter Gunther” posted it, but presumably the speaker is former Congressman Robert E. Bauman(?). (I think he was my Representative way back when, and you don’ wanna know about him, really.) It certainly is a a fine example of a “Buy this book and get rich off the coming misery” sales pitch. I imagine the 70% stock market drop, and 50% housing price drop, must already have taken place, since the video was posted nearly two years ago.

A ponzi scheme of inflated asset prices is just that.

Guessing when it will collapse is the hard bit.

This is what the book “The Big Short” is about.

They knew it was going to collapse, they didn’t know when.

They found CDSs allowed them to make low cost bets on the collapse, until it happened.

I’m a little surprised that this is supposed to be surprising — hasn’t this been understood since the recognition of differing marginal propensities to spend (or its obverse, to save) across the income and wealth distributions? I suppose the busy apologists for neoliberalism have been doing their best to obscure what I take to be obvious, so perhaps I shouldn’t be quite so surprised.

I find it helpful to think of this issue as analogous to metabolic dysregulation — the rich are like the obese whose appetite is never assuaged despite the surfeit of calories they continue to consume, and their mountain of assets like adipose deposits unavailable to healthy circulation. There are, of course, morbidities associated with both conditions; social ones where circulation of wealth is concerned, and physical ones with metabolic dysregulation.

@eg:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2021/05/how-redistribution-makes-america-richer.html#comment-3552382

I recall near the end of Lula’s Presidency in Brazil even The Economist magazine acknowledged the positive impact of redistribution (I wish I’d kept the article, it was written in a tone of such surprise). His policies had brought millions of Brazilians from hand to mouth existence into regular earnings and so created a vast new sector to the economy.

The fact that he was deposed in what looks with hindsight to have been essentially a coup, shows that most of the wealthy classes (in Brazil anyway) are at least as interested in their relative wealth as to their absolute wealth.

Perhaps this is too general and too cynical a take, but Ellen left her show once she got called out on abusing employees. She probably could have kept the slot and kept making oodles of money, but it lost its flavor once the cruelty was gone. Perhaps this is a similar phenomenon, no amount of added wealth can compensate for losing the je ne said quoi of hurting the plebs.

If only someone had had a wealth tax in their platform in 2020. Oh, wait …

And it would be interesting, if the underlying time series were available,

to see the numbers with higher resolution at the top end,

breaking out the 5% minus the 1%, the 1% minus the 0.1%, the 0.1% minus the 0.01%, etc.

New Scientist in the UK had an exchange of reader correspondence on this kind of thing a few years ago. The final word was to the effect that, if you hand spending power to the more modestly placed people in society, it will be in the hands of the rich again by nightfall, so why not just maintain that circulation either by taxing the rich or printing money as seems appropriate? The model here would seem to confirm that approach.

@Psalamanazar: “it will be in the hands of the rich again by nightfall”

A very reasonable concern. This is why the modeling here envisions ongoing, constant downward redistribution. Should probably add “ongoing” to the final sentence of the paper:

“But with adequate redistribution to counter the ever-present trend toward economy-crippling wealth concentration, everybody else prospers as well.”

That’s what was achieved, arguably for the first time in history, in the US 1932-1980. Since then, the eternal tendency toward concentration (with some mind of natural upper limit) has re-emerged.

Even if you could justify unbridle wealth accumulation. You can’t justify what the wealthy do with their money after they make it. You hear the old Neoliberal line “the middle and lower class have never created a job”. The fact is 99% of the upper class haven’t either. What the wealthy do with their money can only be consider a grotesque misappropriation of resources. From the Gilded Age to Larry Ellison its remained the same. Ava Vanderbilt spent $250,000 on a single party in 1883. Larry Ellison currently owns and maintains over 20 homes with an average price of $50 million. 18 of the homes are rarely occupied.

The math is very simple. Which economy is more vibrant. One that creates 10 million millionaires or one with 100 million people making $100,000/yr. We currently have the former

but the latter will be necessary if wealth at any level can be sustained.

Excellent.

I would love to see this kind of analysis conjoined with Figure 6. Mean Income per Adult, Select Percentiles, 1913-2019 –from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44705.pdf (page 19) despite the differences in income data sets.

The shaping of economies and their growth trajectories is very much dependent upon the incomes distribution that exists in any period.

And, yes, your approach reflects some of Keynes thought regarding the Multiplier. Indeed, further development would probably show that what is produced and for whom in domestic and global economies is very much a function of the incomes distribution {as is how resources are used}.

If the oligarchic class were rational in their pursuit of power, they wouldn’t be oligarchs. It’s about a sociopathic will to power, and wealth is the ultimate bludgeon with which to discipline the sub-altern classes.

Interesting artifact of successful neoliberal brainwashing that this data is presented as some sort of hypothetical thought experiment vs a description of the real world that actually existed until the 1970s due to Roosevelt era policies of high marginal tax rates, estate taxes, real tax enforcement etc

V true. Unfortunately the necessary data for this modeling is only available starting in 1989.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2021/05/how-redistribution-makes-america-richer.html#comment-3552385

National Income Accounting

Michael Hudson revealed how national income accounting had been removed from the syllabus of universities.

Richard Werner revealed why this is so significant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EC0G7pY4wRE&t=3s

This is RT, but this is the most concise explanation available on YouTube.

Professor Werner, DPhil (Oxon) has been Professor of International Banking at the University of Southampton for a decade.

The UK’s national income accountants couldn’t see how the financial sector added any value (created wealth).

They must do something, but they didn’t know what, so they bunged a lump sum onto GDP to cover their contribution.

The UK’s national income accountants didn’t know how banks really worked, and how they created money from bank loans, so couldn’t see what they were really doing.

(Different people have different parts of the story)

Banks can add value and create wealth.

Banks – What is the idea?

The idea is that banks lend into business and industry to increase the productive capacity of the economy.

Business and industry don’t have to wait until they have the money to expand. They can borrow the money and use it to expand today, and then pay that money back in the future.

The economy can then grow more rapidly than it would without banks.

Debt grows with GDP and there are no problems

The banks create money and use it to create real wealth

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf