By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

The sixth and latest IPCC assessment report on climate change is out; and prominent in its most optimistic scenario is Carbon Removal (CR), which is planned or fantasized to happen predominantly on an industrial scale with BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage), and to a lesser extent with “natural” solutions like reforestation and tree planting. The title of the post describes my views on the “natural” solutions; I will cover those in detail first, and then briefly look once more at BECCS (which strikes me as just as loony a scheme as it was when I first wrote about it, unfortunately for us all).

Tree planting — erasing a lot of distinctions I am about to make — is a timely topic. From The Applied Ecologist:

Tree planting will receive unprecedented financial, political and societal support in the next few years during the upcoming United Nations’ Decade on Ecosystem Restoration [2021–2030] and as consequence of ambitious initiatives such as the Bonn Challenge and 1t.org. We should not miss this unique opportunity with poorly planned initiatives that may do more harm than good or waste resources without delivering expected outcomes.

Exactly. Before diving into “poorly planned initiatives,” however, let’s ask: What is a forest? Definitions vary[1]. I cannot, perhaps suggestively, find a glossary definition of “forest” at the United States Forest site. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s definition is a little dry:

Land spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ. It does not include land that is predominantly under agricultural or urban land use

Fascinatingly, the FAO qualifies its definition with two notes:

7. Includes rubber-wood, cork oak and Christmas tree plantations.

10. Excludes tree stands in agricultural production systems, such as fruit tree plantations, oil palm plantations, olive orchards and agroforestry systems when crops are grown under tree cover. Note: Some agroforestry systems such as the “Taungya” system where crops are grown only during the first years of the forest rotation should be classified as forest.

Tosh. A Christmas tree plantation isn’t a forest any more than a palm oil plantation is a forest; I can’t think of any reason for the FAO to make this distinction other than, putting it politely, political economy. This is a forest:

Note the fractal complexity.

And this is a tree plantation:

Note the grid-like, profit-optimized uniformity. Or, if you prefer me to demonstrate the same distinction in prose, here is J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the forest of Fangorn in The Two Towers, right before the two Hobbits meet the Ent, Treebeard. I love Tolkien in his travelogue mode:

Meanwhile the hobbits went with as much speed as the dark and tangled forest allowed, following the line of the running stream, westward and up towards the slopes of the mountains, deeper and deeper into Fangorn. … [Pippin] clambered on to a great tree-root that wound down into the stream, and stooping drew up some water in his cupped hands…. The water refreshed them and seemed to cheer their hearts; for a while they sat together on the brink of the stream, dabbling their sore feet and legs, and peering round at the trees that stood silently about them, rank upon rank, until they faded away into grey twilight in every direction… ‘Look at all those weeping, trailing, beards and whiskers of lichen! And most of the trees seem to be half covered with ragged dry leaves that have never fallen. Untidy.’… Just then they became aware of a yellow light that had appeared, some way further on into the wood: shafts of sunlight seemed suddenly to have pierced the forest-roof. ‘Hullo!’ said Merry. ‘The Sun must have run into a cloud while we’ve been under these trees, and now she has run out again; or else she has climbed high enough to look down through some opening. It isn’t far – let’s go and investigate!’… [S]oon they saw that there was a rock-wall before them: the side of a hill, or the abrupt end of some long root thrust out by the distant mountains. No trees grew on it, and the sun was falling full on its stony face…. There, near the fringe of the forest, tall spires of curling black smoke went up, wavering and floating towards them.”

(The “tall spires of curling black smoke” reminds me of Amazonia.) I have helpfully underlined features of a forest that you would never see in a tree plantation, but would see in a forest. Perhaps one useful definition by exclusion: A forest is a system of trees that is not a plantation. We know one when we see one!

Why does the distinction between forests and tree plantations matter? Because forests are a far superior form of carbon removal. From Yale360:

Long-maturing natural forests will eventually store typically 40 times more carbon than a plantation harvested once a decade. “Plantations hold little more carbon, on average, than the land cleared to plant them,” says [geographer Simon Lewis of Leeds University]. The same would apply to proposed plantations of forest to provide biomass for burning in power stations.

That’s because plantations are grown to provide product for profit. From the Guardian:

Commercial tree plantations in Britain do not store carbon to help the climate crisis because more than half of the harvested timber is used for less than 15 years and a quarter is burned, according to a new report.

While fast-growing non-native conifers can sequester carbon more quickly than slow-growing broadleaved trees, that carbon is released again if the trees are harvested and the wood is burned or used in products with short lifespans, such as packaging, pallets and fencing.

“There is no point growing a lot of fast-growing conifers [or eucalyptus or whatever] with the logic that they sequester carbon quickly if they then go into a paper mill because all that carbon will be lost to the atmosphere within a few years,” said Thomas Lancaster, head of UK land policy at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), which commissioned the report. “We should not be justifying non-native forestry on carbon grounds if it’s not being used as a long-term carbon store.”

And then of course there’s the additional carbon used to feed and run the mill, and distribute the product.

Forests, by contrast, grow…. to be forests. From Terraformation:

Trees aren’t the carbon sink. The forest is.

A common objection to tree planting as a carbon capture solution is that the carbon storage is only temporary: supposedly, when trees die, they release their carbon back into the atmosphere. And if it’s temporary, why do it?

As it turns out, this is only (somewhat) true for individual trees, but not for forests.

First, trees don’t release all of their carbon back into the atmosphere. A large portion cycles into the soil as the tree decomposes. Roughly speaking, this is how carbon moves from the air into the soil.

But even more important is that a tree is not an individual, it is part of a system. During a single tree’s lifetime, it seeds many children. By the time that tree dies, there could be many younger ones growing to take its place. The decomposing tree also feeds the soil, making way for other understory growth and eventually an entire food chain.

Together, this ongoing growth takes up all of the CO2 released by the dead parent, and often much more. Decomposition is a slow process, which means that most of the CO2 is either cycled into the soil, or taken up by new plants. All of this new growth contains carbon. Over decades, and even centuries, forests grow denser and continue to multiply their carbon sequestration capacity.

Forests are complex ecosystems, anchored by specific tree species suited to their biomes, and filled out by a web of life dependent on those trees—from bacteria to fungi, insects, other plants, and animals. While it’s tempting to accelerate carbon drawdown by planting swaths of the fastest-growing tree species, plantation-style stands hold far less carbon than forests composed of diverse native species.

…It is the whole system—not just the anchor trees—that is the carbon sink. So while trees alone don’t necessarily offer a durable carbon drawdown solution, forests do.

And now we arrive at “poorly planned initiatives.” Unfortunately for us all, international tree-planting initiatives focus on tree plantations (ka-ching) rather than forests (CR). From Nature:

Plantations are the most popular restoration plan: 45% of all commitments involve planting vast monocultures of trees as profitable enterprises. The majority are planned in large countries such as Brazil, China, Indonesia, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Table S1). Brazil, for example, has pledged 19 Mha to wood, fibre and other plantations, more than doubling its current 7.7 Mha.

Agroforestry accounts for the rest (21%). This practice is used widely by subsistence farmers, but rarely at large scales. Some crops benefit from trees, such as coffee grown under their shade or maize (corn) interspersed with trees that enhance nitrogen in soils. The trees themselves supply fuel, timber, fruit or nuts.

Hence, two-thirds of the area committed to global reforestation for carbon storage is slated to grow crops. This raises serious concerns.

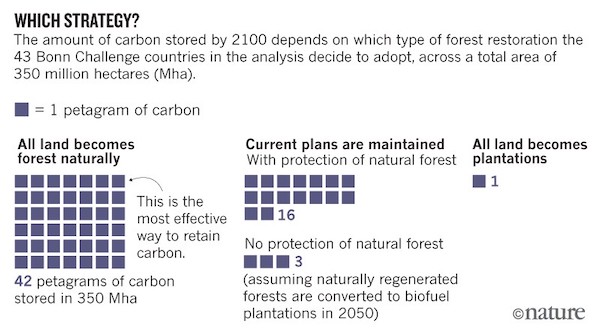

The authors summarize their concerns in this chart:

(By “all land” at left is meant the 350 hectares covered by the Bonn Challenge.) Their solutions are to deprioritize tree plantations and prioritze forests

First and foremost, countries should increase the proportion of land that is being regenerated to natural forest. Each additional 8.6 Mha sequesters another 1 Pg C by 2100. That is an area roughly the size of the island of Ireland, or the state of South Carolina.

Second, prioritize natural regeneration in the humid tropics, such as Amazonia, Borneo or the Congo Basin, which all support very high biomass forest compared with drier regions. International payments to recreate and maintain new forests from carbon sequestration, climate adaptation or conservation funds could mobilize action.

Third, build on existing carbon stocks. Target degraded forests and partly wooded areas for natural regeneration; focus plantations and agroforestry systems on treeless regions and, where possible, select agroforestry over plantations.

Fourth, once natural forest is restored, protect it. This could be by expanding protected areas; giving title rights to Indigenous peoples who protect forested land; changing the legal definition of how land may be used so it cannot be converted to agriculture, or encouraging commodities companies to commit to not clearing restored natural forests.

(Another way to protect forests would be to define them as natural persons, like Lake Erie.)

With regard to natural regeneration of existing forests, this already happens spontaneously. From Yale 360:

Largely unnoticed, many degraded forests are regrowing, capturing carbon and often retaining much of their old biodiversity. [Edward Mitchard of Edinburgh University] has tracked how, as African farmers head for jobs in cities, their old fields are consumed by jungle. ‘If deforestation could be reduced, Africa could quickly become a significant carbon sink,’ he told Yale e360.

Other researchers take a similar line. Philip G. Curtis, a consultant with the non-profit Sustainability Consortium, has estimated that only about a quarter of annual deforestation is permanent. Much of the rest — whether lost to fires, shifting cultivation, or logging — will eventually recover. One assessment estimates that the world contains some 7.7 million square miles of degraded land suitable for forest restoration, a quarter of it for closed forests and the remainder for “mosaic” restoration in which forests are embedded into agricultural landscapes.

Further, protecting and developing actually existing forests is more efficient than starting from the bare earth. From Environmental Health News:

In 2019, [Bill Moomaw, co-author on five IPCC reports ] and his co-authors published a scientific review finding that the capacity of forested lands to sequester carbon dioxide could be increased significantly. They say the fastest way to do this is through what they call “proforestation,” the natural growth and development of standing forest ecosystems.

One reason for this is that newly planted forests may take “decades to a century before they sequester carbon dioxide in substantial quantities,” according to the proforestation review.

Older trees are typically more efficient carbon extractors than younger trees (in comparable environmental conditions) because, as trees get larger, they add more carbon rich mass each year than the year before. For example, one study found that, on average, a 100 cm diameter tree added biomass at three times the rate of a 50 cm diameter tree of the same species.

Moomaw advocates for an expansion of protected lands where forests are allowed to grow and develop, uninterrupted by resource extraction, as soon as possible.

“Proforestation will sequester more total carbon in the near term, when…it’s most important to do it, than anything else that is out there,” he said.

A good test for what Biden does with public lands, assuming public lands haven’t gone the way of public health.

Before turning to BECCS, a sidebar on pricing. From MIT Technology Review:

We know forests, soil, peatlands and other natural systems absorb significant levels of carbon dioxide, but it has proved challenging to develop markets and systems that reliably incentivize, measure and verify it.

I don’t think it’s challenging. I think it’s impossible (as I argue here). Similarly, from the Financial Times:

The scientists called on governments to end subsidies for activities that harmed nature, such as deforestation and overfishing, and said “clear accounting standards” for carbon offsets — which vary in quality and legitimacy — should be agreed at an international level.

We don’t even have clear accounting standards for business; what we have is the Big Four. So we’re going to be able to audit nature? I don’t think so. End sidebar.

And now BECCS. BECCS is tree plantations on steroids, and BECCS seems to be where the IPCC has placed all its chips. From the MIT Technology Review:

The model used to create the most optimistic scenario [SSP1-1.9] in the report [ which limits warming to 1.5 ˚C, assumes the world will figure out ways to remove about 5 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year by midcentury and 17 billion by 2100.

That requires ramping up technologies and techniques capable of pulling as much CO2 out of the atmosphere every year as the US economy emitted in 2020. In other words, the world would need to stand up a brand-new carbon-sucking sector operating on the emissions scales of all America’s cars, power plants, planes, and factories, in the next 30 years or so.

In the model above, nearly all the carbon removal is achieved through an “artificial” approach known as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, or BECCS. Basically, it requires growing crops that consume CO2 and then using the harvested biomass to produce heat, electricity, or fuels, while capturing and storing any resulting emissions. But despite the billions and billions of tons of carbon removal that climate models are banking on through BECCS, it’s only been done in small-scale projects to date.

“Only been done in small scale projects” was also true in 2018, when I wrote:

BECCS is going to require a lot of land for a lot of crops. First, let’s look at the requirements for land. Again from the EASAC:

Given the need to remove several gigatonnes of CO22 from the atmosphere using BECCS, very large amounts of biomass would be required. In their 2015 review of [Negative Emission Technology (NET) like carbon removal], the National Academy of Sciences (National Research Council, 2015) assessed the land, water and nutrient requirements of dedicated energy crops. They estimated that producing 100 EJ/year (EJ, exajoule: 1018 joules) (approximately 20% of global energy production) could require up to 5% of the current land surface (excluding Greenland and Antarctica) – 500 million hectares22 – on the assumption that approximately 10 tons of dry biomass are produced per hectare annually.

22 500 million hectares: 1.5 times the size of India.

That’s a lot of land. Where does it come from? That’s a problem. From Nasim Pour’s 2018 thesis, “BECCS: Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and StorageSustainability, Challenges,and Potential” (PDF):

Most assessments for sustainable bioenergy crop production use abandoned agriculturalland, degraded land, marginal land and waste land unused agricultural lands, which is estimated to be between 320 and 580 Mha of low productivity land. Chum et al. argued that although using marginal lands for bioenergy production is often seen as an option to avoid land use change, its low productivity, long distance to bioenergy plants, loss of biodiversity and the competitive use of land by the local communities, could be a challenge. In addition, remoteness of marginal lands and their long distance from the centralised bioenergy facilities may result in logistic and economic challenges.

So it’s not like we can simply turn the subcontinent of India into a sacrifice zone for biomass. And what if we did? To begin with — at least under current politico-economic constraints — we’d grow our biomass on plantations as monoculture. (Leaving aside the notion that biomass plantations will be in direct competion with food crops for arable land, moncultures are not resilient. Take for example the eucalyptus trees of Portugal, imported to be used for as a cash crop for paper and pulp. (Hello, Unorganized Territories!) From Geoengineering Monitor, “Fire and Plantations in Portugal“:

2017 in Portugal will be remembered for extreme heat waves, severe drought, and catastrophic forest fires. Half a million hectares of land burned, equivalent to 5 percent of the national territory the greatest yearly total in the country’s history. [Portugal] has more land planted with eucalyptus than any other EU country. Concentrated in the northern and central regions, roughly 10 percent of Portugal’s land area is planted with Eucalyptus globulus, an exotic, highly invasive, fast-growing subtropical tree…. The harm caused by fires in Portugal in 2017 was unprecedented. …. Satellite mapping of the infamous Pedrogão fire has shown that eucalyptus and pine plantations covered around 70% of the burned area, and that these areas experienced high fire severity.

OK, you say, we’ll plant trees that don’t catch on fire, even with high(er) winds and hot(ter) temperatures. Fine, but monocultures are also not resilient against birds, bugs, fungus, bacteria, viruses, you name it, because when one individual goes, they all go (absent toxic chemicals from Monsanto, and so forth.). Not enough land, bio-energy crops that could end up like your tomatoes when blight hits. So the input side of BECCS looks like an enormous and extremely vulnerable single point of failure.

Because that’s what a monoculture is. So naturally, we’re betting on BECCS. From the Financial Times:

Planting single species crops that are used as the fuel for bioenergy — renewable energy that produces heat and power — is “detrimental to ecosystems when deployed at very large scales,” the researchers said.

Yet bioenergy as a replacement for fossil fuels is being written into emissions reduction blueprints by groups including the influential International Energy Agency and the UK’s Climate Change Committee, which advises policymakers.

Anyhow, one thing at a time. If we can at least mentally distinguish forests from tree plantations, and discredit tree plantations for the greed-driven and anti-CR schemes that they are, that will be good. BECCS strikes me as an enormous Rube Goldberg ex machina, bound to collapse from its own flimsiness, useful as a forcing device, and nothing more. So we’d better think of something else. And if we can’t, well, a world with more forests in it is better than a world with less forests in it, no matter the temperature.

NOTES

[1] There are many, many definitions of forest, perhaps as many as the uses to which forests are put. Out of scope for this post are individually planted trees, urban trees (as problematic as tree plantations but for different reasons), and food forests (see NC here, here, and here). I am also not going to worry about edge cases like copses, thickets, hedgerows, or groves.

Here is a pdf of the travesty that happened in Vermont. The Abenaki were stewards of a primeval forest-covered land for thousands of years. Then came the Europeans. We are back to mostly forest cover now, but the species of animals and plants lost will never return.

https://glcp.uvm.edu/landscape_new/learn/Downloads/scrapbooks/forests2.pdf

This “scrapbook” made me want to throw up a little, but it tells the tale.

That travesty happened all over the U.S. in the last two centuries. In my Southeast there are only a few patches of old growth left. But here at least the forests do come back fast. This year’s summer growth is incredibly lush.

@Carolinian

August 15, 2021 at 7:50 pm

——-

It’s also been a very good year along the Alabama Gulf Coast for growing practically anything. All of my plants, both in the yard and potted have been thriving since the end of winter (late Feb.).

The pine “plantations” in the flats of the Coastal Plain of Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina look like forests from the road, but “growth” is indeed a better term. We called them “woods” as kids, and they were full of snakes, ticks, chiggers, feral pigs, and the occasional bobcat and whitetail deer. The more growth the better, though! The banks along the blackwater rivers are especially magical, and alligators are common again. The understory of the plantations is ecologically unnatural and these woods are much less than the longleaf pine forests of the sandy flatlands or the mixed pine-hardwood upland forests above and below the fall line that preceded them, in both flora or fauna. The saying is that a squirrel could travel from eastern NC to the Mississippi River without touching the ground before the 19th century, except for the rivers, of course. One encouraging thing is that tree farmers in Georgia are planting longleaf again! Probable proximate cause is tax breaks, but who cares?

US and Canada, Carolinian and AE90. The settler Europeans did the same in both territories. I’m reminded of a comment by John Ralston Saul, that it was not the indigenous tribes, but the settlers who were the nomads. Many tribes had a summer home and a winter home, something we consider a sign of wealth. Both the mythologies and the practices were indicative of the humans being a part of the system, not a lord over that system. We just use up the earth and its bounty, then move on. That’s over. Now there is no more “on” to move to.

“China’s forest coverage rate rose sharply from a mere 8.6 percent in 1949 to 23.04 percent by the end of 2020, a sharp increase of 1.6 times, according to the latest statistics.“

http://en.people.cn/n3/2021/0629/c90000-9866358.html

I was pretty surprised to read about their efforts.

https://unravel.ink/lessons-from-china-on-increasing-forest-cover/

Thanks for te Unravel link. I simlpy cannot imagine any neoliberal ‘democracy’ doing anything like this, even wanting too (or is that ‘to’?) – let alone doing it.

There is a huge problem with Chinese afforestation in that they’ve historically had a poor understanding of the correct ecology of forests. A vast amount of Chinese plantation has been on land which is ecologically probably natural semi-arid grassland and prairie. Its questionable whether those forests will survive without intense management and they may well actualy make water management worse in that forestry will lower natural ground water levels, increasing the desertification they are trying to prevent. They are learning (the hard way) that afforestation is not really something you can plan by decree from an office in Beijing. Much of the problems with desertification in the northern fringes of China come from the destruction of the natural herding way of life there with its replacement with Han populations who try to make arable land where such cultivation is entirely unsustainable.

Plus there is the usual problem that any official statistics from China should be taken with a very large grain of salt.

It seems to me that BECCS is two different ideas stitched together for no good reason – we either can directly capture the CO2, at which point why don’t we just continue burning coal/gas? Bound to be simpler and more efficient.

And on the other side, if we want to scrub the air, why bother burning the biofuels in the first place?

Just dig a hole, put the biomass in it, put a clay liner ontop to stop methane leakage, and then soil and whatever until it looks like it did before.

The area where I live was clear cut of redwoods shortly after SF burned in 1906.

It’s a mess, Redwood top canopy, Bay and Maple beneath and saplings and shrubs on the lowest level.

None of it cared for for more than 100 years except here and there.

When I moved in I took out 18 Bay trees and two Maples that were scraggly and much too crowded.

Redwood mulch is free in my neighborhood so I initially brought in 12 yards , planted 70 native ferns and a dozen tree ferns.

And I’ve added 6 yards of mulch a year for the last 4 years

There’s not much sun so my garden is trees, ferns and forget me nots.

The trees are drought stressed throughout the County and most of the Redwoods are showing brown tips on their branches.

The idea of planting forests is nice, but in a lot of areas the changing climate is going to make the choice of which trees to plant crucial.

Redwood forests are dear to me. I don’t think many know that Northern California, especially the San Francisco Bay Area, has clay for soil even though the weather is good. Even when it rains, without forest, all that water washes down the hills to the ocean, which is why the soil here, like in the Amazon, is awful. The local forests, especially the Redwood forests, recycle everything as well as acting as a sponge for the rainfall. That is how they can survive at all. This is not to mention how much carbon goes into a single three hundred foot tree.

Cutting down so much of the local forests has made the remaining trees more susceptible to everything including drought. Forest do help to create the conditions favorable to them, but having larger forests must be more effective than smaller ones, and most of the Redwoods have been cut down. It must have been awesome to see the vast forest that covered Oakland, San Francisco, Marin County, and beyond.

So not only is the choice of what kind of trees to plant important, but also (re)introducing all the complimentary species like the ferns, mosses, insects, animals, even other tree species that live in a Redwood forest, and make living in such a difficult environment possible. There is a reason why even with with poor soils and unpredictable water as in coastal California, Redwood forests have thrived or away from the coast, oaks, and it is not just the trees themselves. The Amazon jungle and the Redwood forests have thrived because of the efforts of the forests themselves and not, or sometimes despite, the local environment, which does make things harder and easier. It can be harder to create a successful forest, but the areas where they can be create is greater than it first looks.

I have read that a lot of the water-input the redwood forests receive is from fog condensing on redwood leaves and finally falling to the forest floor. A 300 foot tall redwood can scrape a lot of water out of foggy air.

yes, its what thatcher did to the u.k unions when she forced the u.k. into the E.U.

but also the democrats had turned on mcgovern types as well. volker and another idiot jimmy carter put into power alfred khan, i called him the great con. both volker and khan hated union’s and viewed them as impediments to corporate profits, which the idiots thought was a great contribution to GDP, and union wages were inflationary.

of course anyone who understands capitalism knows that wages drive consumption.

so by the time of bill clinton came along, that mis-understanding of how capitalism works, had degenerated completely into pummeling the deplorable for all of the ills wrought on americans by government officials that worship the role of the wealthy in our economy.

they simply are to stupid to understand what they wrought, so they place the blame onto others.

bill clinton scolded the deplorable when they complained he was over turning the new deal, billy said how long do you think you can live under the new deal?

well since it was the best interpretation of the constitution, then i would say as long as we have america.

that dim wit thinking was echoed loudly by hillary clinton in 2016.

bill clinton knew exactly what he was doing, and he should be called out for it and made a pariah.

@lance ringquist

August 15, 2021 at 10:40 pm

——-

Respectfully, lance, is this the post you actually wanted to comment on? Your comment seems way off topic.

Not only is this post seemingly irrelevant to the article, its first sentence is historically inaccurate. When the UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973 after a public referendum, Margaret Thatcher was Secretary of State for Education and Edward Heath was Prime Minister.

Lambert – Thank you once again for a most excellent learning experience. I had a feeling that tree plantations weren’t going to be all that great, and you’ve shown the evidence.

I don’t want this to sound like an assignment, but your posts on living in harmony with the natural world are invaluable and I hope you’ll continue writing them.

I’ve let an oak tree sapling keep growing next to my driveway and I hope it will mature into a great tree in the next 50 years or so. Not a forest, but with all the 70-80 year-old oak trees my neighbors have been cutting down, it’s the least I can do.

1. No really substantial reforestation is going to happen.

2. The scheme wouldn’t work in any event.

Try curing measles by painting the spots.

I know the subject is “forests” and not “trees”. But you can’t have a forest without trees.

Here is a French film ( a French ” documentary art-film” if such a category may be said to exist) about the founding past, neglected present, and re-emerging future of pollarded trees and pollarding of trees in France.

It was presented on Colonel Lang’s Sic Semper Tyrannis blog which is usually political one way or another, but this was something completely different.

The film is called ” Des Trognes — Trees of a Thousand Faces”. It is in French without even subtitles. And it shows much footage within the semi-wild semi-managed forests and wood-edges and so forth of France. It is only mildly didactic. Rather, it is at least as much “aprehensionogenic”, that is, it quietly offers things which may be apprehended if you already have enough knowledge to be able to apprehend them, Some of these things only appeared to me after 2 or 3 viewings, which never became boring.

Here is the link to the relevant blogpost, which itself contains links to the watchable movie.

https://turcopolier.com/des-trognes-trees-with-many-faces/

Soooo…. I recall that another source of carbon sequestration is blue green algae.

Cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue green algae or bacteria, are unlike most bacteria. … Cyanobacteria account for 20–30% of earth’s photosynthetic productivity. The bacteria have a phenomenal carbon-absorption rate, with each hectare soaking up one ton of CO2.

SURELY the report mentioned this as a possibility.

BG algae can grow in fresh, salty or brackish water. They produce a lot

of oxygen as well.

our old cowboy pool(6’diameter, 2′ deep steel water trough) retired a couple of years ago as a cattail pond.

2 big tubs that used to contain cow minerals, liberated from the dump, filled with that woody city produced mulch…and planted with cattails i dug up at the river.

but i dug them up downstream from where the creek that the city’s “wastewater treatment plant”(some ponds and stuff) discharges into the river.

so some of the abundant blue-green algae spores(?) came along for the ride.

i haven’t had time to investigate what i can do to knock that back without harming the cattails, frogs, dragonfly larvae, etc etc….so i’ve been using a leaf rake to remove the abundant cyanobacter mats(similar, it turns out, to the stromatolites found along that same river, representing billion year old life)…and composting them in a bed that’s right there.

too soon to tell anything, since i only started this in may, concurrently with my ongoing and layered chaostimes.

but it does seem to have some aleleopathic quality….suppressing weed and grass growth/germination.

i’ll plant something in it next spring and see how it goes.

I don’t think we have the luxury of devoting ourselves to one ideologically preferred approach as against another to planting trees. There are too many people and there is too little unspoken-for land to be able to re-devote large amounts of it to “set and forget” forests. We can certainly try to establish or re-establish set-and-forget forest wherever such centuries-long commitment of certain land areas can be permitted or tolerated. Elsewhere, we will have to make do with “planting trees” in such a way that more-than-zero skycarbon is sucked down and held down by the planted tree zones.

And with climate violently shifting faster and faster, we may have to try all kinds of new combinations of trees in new places. A visible model of that sort of thing happening by accident has been seen to happen on Ascension Island. It can be studied and perhaps versions of that approach tried on purpose in other places where a self-maintaining forest is desired. Here is a link to an article about the accidental neo-forest on Ascension Island.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18324656-100-the-accidental-rainforest/

Where in America specifically might a non-tropical version of such a mix-and-shake grab-bag-of-species neo-forest be tried? Perhaps on the hundreds of thousands of acres of lunarized abandoned strip mine land throughout Appalachia? Perhaps spread and mix just enough broad spectrum fertility minerals on some targeted abandoned strip-mine land-wreckage and plant bunches of fast and ultra-fast growing trees and weedy trees and trashy trees to see if they take hold and begin forming an accidental forest which might eco-remediate the habitat just enough to allow other kinds of trees to get established by naturally incoming seeds . . . on the wind, in mammal fur, in bird poop, etc.

It turns out the Ascension Island link is mostly non-visible. So here is link to another article somewhat about creating that grab-bag forest on Ascension Island.

https://unbelievable-facts.com/2018/04/ascension-island.html

One problem with estranging people from nature is that they can no longer tell the difference between a natural forest and a plantation. The trailer for a new movie, The Green Knight shows a few forests I’m pretty familiar with – the film is supposed to be set in Arthurian Britain, but the forest scenes are mostly in Irish conifer plantation forest. Some of the scenes were shot a few miles away from real oak/holly forest that would have been close to reality. I wonder if the director simply felt that the bareness and geometry of a plantation looked more ‘real’. This isn’t the only example, there are numerous similar examples from Game of Thrones, the Vikings, Excaliber, etc. One of the places shown in that film is a big Instagram hit, such that recently I’ve been twice asked by friends to bring me to see it. It does look good, but its still plantation (its actually the parallel geometry that seems to make it so photogenic).

I think another element is the human obsession with control. We seem to resist the notion that it can make sense to just let land be. In Britain and Ireland, and I’m sure in most countries, there are vast areas of low grade land which is only marginally profitable for farming or plantation – and often only then with government subsidies. So the cost of just fencing them off from grazing animals for a few years and just let nature take its course would be miniscule in overall terms. But we still just can’t help trying to ‘extract value’ in one way or another by imposing increasingly complex schemes for ‘integrating harvesting with ecology’ or some such nonsense. We just can’t help ourselves.

I’m not sure it’s always been this way. Maybe it goes back to the closing of the commons or with industrialization and taking so many people off the farms. But even farmers these days don’t even remember what farming is, they really just operating industrial factories that look different from traditional manufacturing plants. Traditional farms generations ago lived cyclically with their soil. They planted a variety of crops on rotation and had livestock mixed in that rotation as well. A traditional dairy farmer isn’t farming cows for milk, he’d farming grass which is converted by the cow into milk. His farming focus was on insuring healthy pasture for his cows. Most modern dairies don’t even have pastures and some don’t even grow anything, it’s all just shipped in. There’s no connection between the output and the soil anymore.

When you see cows let out to pasture in the spring, after that long wet winter, they kick up their heels and frolic. That is one of the spontaneous joys on a farm, where nature reminds us of rhythms that might otherwise escape our notice. I recommend more school field trips and less cell phone coverage.

The Swedes have a word for it: kosläpp. It’s the day the cows are let out of the barn after the long long winter. Don’t stand in the barn door, because you will be flattened by an ecstatic cow rushing to pasture!

Ko is cow. Släppa ut is to let out.

around 20 years ago, during a local/regional farm crisis precipitated by the late-clinton farm bill, local ranchers suddenly discovered “Grass Fed Beef”…and, to their credit, made a pretty good(and more or less sincere) go of it.

as the local organic hippy dippy sustainability guru in these parts, i was asked by all and sundry about all this….my idiosyncrasies suddenly forgotten.

my advice:” you’re not growing cows…you’re growing grass…focus on the grass, and the soil that makes it possible”.

there are still a few local rancher types who are doing this, today…but they’re apparently having difficulties with access to markets…can’t seel in grocery stores, because of the regs and “industry standards” that are geared towards IBP and Cargill.

they are mostly rather well off…having much income from elsewhere(they ain’t making a living from grass fed beef)…so a few got together to open a storefront on the square.

been there since the beginning of the pandemic…so i assume they have enough extra jack to keep it going without hordes of peasants beating down their doors to buy high priced lean beef.(their prices are almost double what you pay for the CAFO beef in the regular grocery store.)

if they’re still around next spring and summer, when i hope to be a mere farmer, again(instead of an infrastructure/construction guy), they’ll take my produce on consignment.

Here in Ann Arbor, there are venues outside the Cargill/Conagra/Etc. channels for cattle-on-pasture mini-growers to sell their strictly-grassfed beef. Perhaps it takes a community at or over a size-and-wealth threshhold to have enough people willing to pay a shinola price for grassfed shinola beef. Is there such a just-large-enough customer base for shinola beef within reach of the ranchers you write about? Is such a thing as possible in Texas as it is here in Michigan?

not that i can see,lol.

majority around here are at best lower middle class.

and that’s increasing.

i suppose the handful of rich folks around here could absorb a lot of beef at their soirees….which never ceased during all this time, btw.

pandemic and all i haven’t talked to those guys at length since they opened…just in passing with the 2 i’ve known a long while.

i’ll bet a dollar that they freeze and ship.

As long as they have a customer base who can/will pay for frozen-and-shipped, they can afford to keep standing on the land and growing eco-correct pasture beef.

If eventually the freezing and shipping parts of the process can be powered totally by renewable energy electricity, then their business model can continue. If renewable electricity never becomes affordable and available enough to freeze and ship beef to customers, then they will have to find another way.

Even if reforestation projects plant the best species, land availability is a significant problem:

https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/08/05/news/oxfam-reforestation-hopes-threaten-global-food-security

throughout all this, i’m of course looking at it through the lens of my place, in the (formerly) arid NW Texas Hill Country.

all my raised beds are…or will be…in partial shade…because it generally gets so dern hot here(and always has…last 3 years are the exception)

plant things in “full sun” like all the seed packets say, and you’ll be either watering every day, or looking at dry, brown desiccation.

i do shade cloth while the fruit trees are getting big enough to matter in this regard…and the bigger trees will take much longer:native pecans(mostly squirrel planted) and native oaks, with a few cottonwoods and 2 pine trees(because i’m from East Texas)…as well as several potted Xmas Trees we’ve planted after the lights came down.

I’m also allowing numerous mesquites to grow(mom hates this:ocd about mesquites)…for shade and eventual coppicing. the latter are aleleopathic, so i plant kushaws and cukes in pots elsewhere, and move them under the mesquites after they germinate…grow all up in the tree,lots of air movement, so few issues with mold…and the squash/cukes hang down for picking. orchard ladder with a pointy hook for those out of reach.

my point is that “crops” vs “trees” is not necessarily a thing…and “agroforestry” need not be cereals and other tractor driven crops…but can be horticulture, too.

Are mesquite trees able to live in your part of Texas? If they are, have any selections been made for best most-edible-pod mesquite trees? If so, would it make long run sense to plant just enough mesquite trees in just the right orientation to your raised beds that eventually their feathery-leaflet branches would cast a shade-cloth type shade over the beds? While yielding edible pods too?

they’re all edible…just some are sweeter…”honey mesquite”. can’t tell them apart visually.

and yeah…dominant tree hereabouts, since the spanish cattle shat them out on their way …and fire suppression got going in earnest.

the pods make a nice flour…gluten free, with complex, diabetic friendly carbs and sugars(per my research)…good for pancakes and cornbread(mixed with flour and corn respectively)

high fiber, though, so watch out, and keep a clear path to the bog.

high efficiency firewood, amenable to severe coppicing…and the sticks make great charcoal(for tiera prieta)

A friend worked for Tulare County, and told me the higher ups in politics here described the vast forests in the Sierra as ‘Straws’ for they take away for their own use, water that could be more appropriately used for Big Ag.

Walked up to the Arm Tree yesterday and our forests which in the 19th century it was said a person on horse could easily ride between trees that were typically 15 feet apart, now have the look of a mad gardener who planted 1000 carrots where 100 should’ve been in terms of spacing.

A great book on the subject came out in the 1990’s, a fellow found the exact locations of where photos were taken from 1849 to around 1900, and duplicated the photos now, it was stunning-the difference. The reason being that we suppressed all fires since as much as possible, a major blow it!

Fire in Sierra Nevada Forests: A Photographic Interpretation of Ecological Change Since 1849 by George Gruell

Maybe the political higher ups will get legislation calling for cutting down all the straws on certain dam-filling watersheds, so the water not wicked away will fill the dams more.

And if the de-strawed watershed mountainsides all landslide and erode all their soil and subsoil into the dams with every raindump waterbomb rain event, well . . .”oops”.

If you are interested in forest managment, this is a good guy to follow. Convincingly promotes letting forests do their thing and criticizes the various arguments about why we need to involve ourselves by lumbering, prescribed burning, thinning.

https://youtu.be/xeVLy3gfUhw

Maybe we need, or at least want, some lumber from time to time. And didn’t the Indians do their own prescribed burning? Wasn’t it Indian Burning which created the forests which the first EuroInvaders found so delightful?

In India, there are many ‘sacred forests’ . People in and around protect a forest as god’s forest by following traditions and practices that facilitate protection. Here is one link to photos from such a forest.

https://wanderingmaharashtra.com/2020/08/18/devrai-sacred-grooves-articles/

Unfortunately, media and politicians in the West seem to have an unwritten rule of not mentioning these things because there is a certain religious angle to their thinking. In some cases, where some corporate raider wants the land, the media can easily scapegoat the traditions by claiming some modern moral stuff like women’s rights or whatever. I bring it up here just to make you aware that there are non-legal ways of protecting a forest.