Yves here. VoxEU regularly runs research that demonstrates the long tail of historical events. One has to wonder what the causal link is between slower economic development and religious tolerance v. persecution. While it’s easy to see deeply religious areas as conservative and therefore resistant to change, the authors put weight on the idea that persecution weakened trust.

By Mauricio Drelichman, Associate Professor, Vancouver School of Economics, University of British Columbia; Jordi Vidal-Robert Lecturer, School of Economics, University of Sydney; and Hans-Joachim Voth,UBS Professor of Macroeconomics and Financial Markets, Department of Economics, Zurich University. Originally published at VoxEU

Throughout history, religion has influenced growth and per capita output, and its effects are felt even in modern times. This column investigates the effect of one of history’s longest-running and most intrusive forms of religious persecution – the Spanish Inquisition. In areas without measured persecution, annual GDP per capita is significantly higher than in areas where the Inquisition was most active. Local levels of persecution continue to influence economic activity and basic attitudes some 200 years after the abolition of the Inquisition, undermining trust, reducing investments in human capital, and impoverishing hardest-hit areas.

In Monty Python’s famous sketch, “nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition” – an institution so brutally backwards, so anachronistically cruel that it can only serve as a butt for jokes. While Western audiences today may chuckle, religion was no laughing matter to rulers for most of human history; from the days of Nero to North Korea today, religious persecution has been frequent and often severe. Johnson and Koyama (2019) recently argued that religious freedom only emerged once rulers could be legitimate without being divine or heads of the church. What are the economic consequences of religious persecution?

A rich tradition in economics, going back to the work of Max Weber, has already investigated how religion can influence growth and per capita output. Recent research in the economics of religion has increasingly married micro-data with rigorous quantitative analysis: while Cantoni (2015) showed that Protestant areas of Germany did not outperform after the Reformation, Becker and Woessmann’s work (2009) demonstrated that Protestant areas of Prussia were richer largely because education levels were higher. Squicciarini (2020) has recently found that Catholic areas of France only began to lag during the Second Industrial Revolution when human capital grew in importance.

The effects of religious persecution are less clear. While the expulsion of economically useful minorities cast a shadow and Chinese persecution of intellectuals may have reduced human capital accumulation (Koyama and Xue 2015), reducing population pressure in other settings may have been beneficial (Chaney and Hornbeck 2016). Becker et al. (2021) examine whether the ban on book printing in Catholic areas during the Renaissance was economically harmful, and Hornung (2014) demonstrated that Huguenot emigrants from France provided a boost to Prussian growth.

Measuring the Inquisition’s Impact

In our recent paper (Drelichman et al. 2021), we investigate the effect of one of history’s longest-running and most intrusive forms of religious persecution. The Spanish Inquisition was founded in 1478 and operated until 1834. It aimed to root out all manners of heresy, from crypto-Judaism to sorcery, from blasphemy to sodomy, from the possession of forbidden books to hiding a wanted person, and a whole range of other behaviours and beliefs in between. It persecuted tens of thousands of Spaniards and foreigners, handing out sentences ranging from mild punishments like imprisonment to spectacular public executions. It had the rank of Crown ministry – notably independent from the ecclesiastical hierarchy – and financed its operations from the fines and confiscations it imposed.

Denunciations were the fuel on which the Inquisition ran. Neighbours, business partners, family members, and local notables were essential to identify potential targets. Those accused of major heresies were often subjected to torture. The modus operandi of the Inquisition created strong incentives to limit social interactions to a close circle of friends and family; its focus on persecuting new ideas and its incentive to persecute wealthy citizens to self-finance discouraged entrepreneurship, education, and innovation.

To examine the long-run impact of the Inquisition, we construct a new, comprehensive database of the geography of religious persecution in Spain for the entire duration of the Inquisition’s operation. While many of the rich files on local trials have been lost, Inquisition tribunals sent annual summaries to Madrid between 1540 and 1700, which have largely survived. As part of a collaboration with the Early Modern Inquisition Database, we digitised the universe of these records and merged them with existing secondary sources to obtain over 67,000 trial observations.

We then geo-reference the location of persecution – either the accused’s place of birth, his or her place of residence, or the location where the offence was recorded. We measure the Inquisition’s impact as the proportion of years during which a trial was initiated against at least one member of the community.

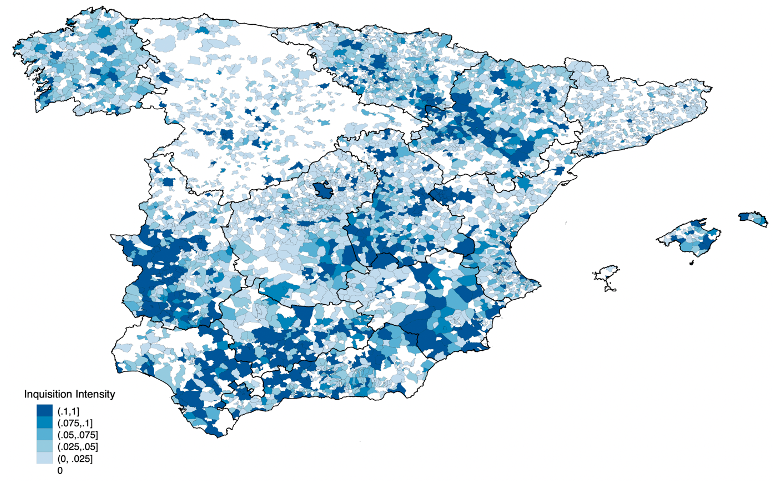

Figure 1 shows a map of the Inquisition’s local impact. The geography of religious persecution in Spain reveals sharp differences, often over short distances – but not a clear North-South gradient.

Figure 1 Inquisitorial intensity in Spain

Notes: The map gives values for inquisitorial intensity by municipality, for the period 1478–1834. Intensity is defined as the number of years a municipality experienced at least one inquisition trial divided by the number of years for which municipality-level data is available. The largely white area in the Northwest – the tribunal of Valladolid – is the result of unusually high levels of missing data, and not of lower persecution. Source: Drelichman et al. 2021.

In order to measure the economic impact of the Inquisition on today’s world, we turn to nightlight. Reliable measures of GDP at the local level only exist for municipalities with over 1,000 residents (25% of all municipalities). Estimates for smaller towns, based on income tax receipts, are unreliable because of widespread tax avoidance (Domínguez Barrero et al. 2014). We therefore estimate the relationship between nightlight and GDP for the larger municipalities and then extrapolate to the rest.

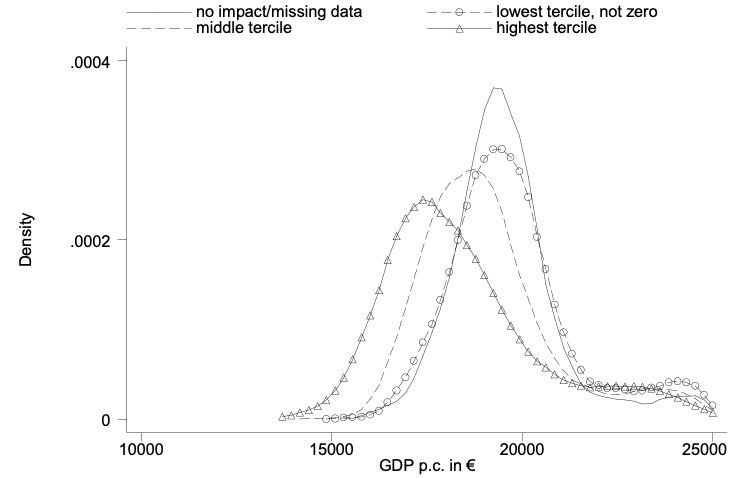

Doing so suggests stark differences in income today, almost 200 years after the end of the Inquisition. Figure 2 shows distributions of income for areas with no recorded persecution, as well as for the three terciles of the Inquisition’s impact. In areas without measured persecution, annual GDP p.c. is €19,450; in areas where the Inquisition was active in three years out of every four (highest tercile of persecution), the average is €18,000.

Figure 2 Inquisitorial intensity and economic performance

Source: Drelichman et al. (2021).

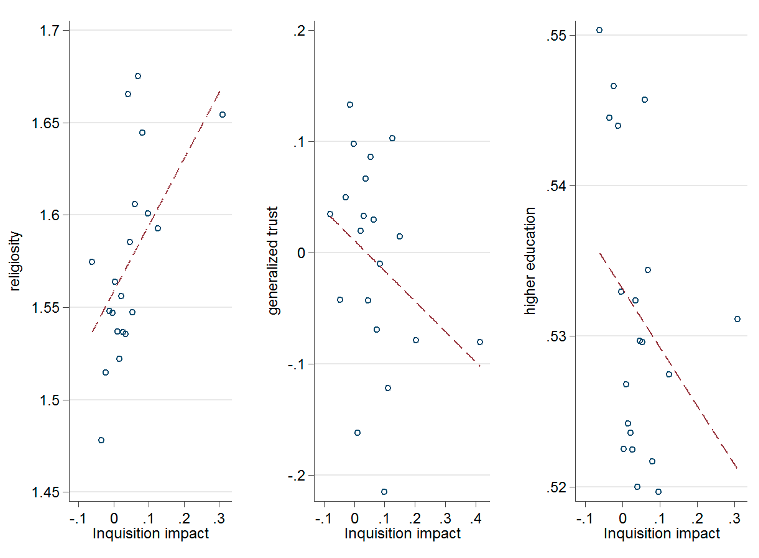

Why does the Inquisition cast such a dark shadow over economic performance – even today? We use data from the barometer surveys conducted by the Spanish Centre for Sociological Research (CIS). On average, areas that suffered more from religious persecution are today more religious and less educated, and they exhibit less generalised trust. The adverse impact on output, education, and trust is robust to a wide variety of additional controls.

To account for the possibility that the Inquisition targeted poorer, more religious, and less educated areas to begin with, we use three strategies. First, we form comparison groups of closely-matched municipalities with near-identical characteristics; we still find consistent, large differences between those that suffered more and those that suffered less religious persecution.

Second, we show that municipalities that attracted larger inquisitorial activity were less likely to produce prominent religious figures. Finally, we use data on the presence of early modern hospitals as proxies for wealth and social capital to show that the Inquisition was more active in richer areas (which is also consistent with the Inquisition’s need to self-finance).

Figure 3 Inquisitorial intensity, religiosity, trust, and education

Conclusion

The Inquisition’s persecution of perceived heretics is only one example of authoritarian intervention in people’s private lives; other institutions, such as Stalin’s NKVD and Hitler’s Gestapo, instituted similarly intrusive regimes of thought-control (Saxonberg 2019). While the suffering of the accused and convicted is the single most important result of persecution, our results suggest its shadows can be long indeed. In the case of the Spanish Inquisition, the local level of persecution continues to influence economic activity and basic attitudes some 200 years after its abolition, undermining trust, reducing investments in human capital, and impoverishing the hardest-hit areas.

See original post for references

Thank you, Yves.

From 2008 – 14, I was often seconded to the Swiss Bankers’ Association and got to know the Lombard and Odier families, the former from the Italian lakes and the latter from the Rhone valley. They talked about this sort of thing and how Geneva and what became the U.K. benefited from such persecution.

This said, what became Northern Ireland prospered for a time with such discrimination.

I didn’t do the numbers, but the regression lines on those plots look pretty dubious.

Agreed, those plots mostly look like noise that just happens to skew very slightly toward the authors’ thesis. Even if the line fit is meaningful, is there really a significant difference between a religiosity score of 1.55 and 1.65?

I’m looking if you remove the single outlying points, the regression line shows an inquisition impact of ~0.

It would be interesting to perform the same analysis on US satraps.

Starting with Canada and Great Britain, Great Britain’s performance since WW 2 (which includes the lease/lend process) would very illuminating.

And even some US states.

Also to compare it with Spain under the Moors who were for the most part tolerant of other religions, including Sephardic Jews of whom about a 100,000 were expelled from Spain in 1492 at the edict of that delightful couple Isabella & Ferdinand. Muslims then rescued many by dispatching the Ottoman fleet to pick them up & deliver them to Greece & Turkey.

The Ottoman sultan of the time, Bayezit II, is quoted to have remarked about Spain’s 1492 expulsion of Sephardic Jews, “You call Ferdinand a wise king, he who impoverishes his country and enriches our own.”

The Spanish king repeated the procedure with the expulsion of the muslim population in 1609; some 300000 moriscos fled to North Africa. In the regions of Spain where they had still been present (mainly Aragon and Valencia), the expulsion led to a collapse of the agriculture and a massive drop in tax receipts, with a long-lasting depressing effect on the local economy of those regions.

They did however leave an amazing long term legacy that has since swelled Spain’s coffers with probably No.1 on a long list of amazing sites being the Alhambra & I believe that flamenco has it’s roots in the Maghreb as most definitely does the vernacular architecture in the South, all of which Spain would be a much poorer place without.

It could perhaps have been worse if Isabella had been short sighted as one of her suitors was Richard III.

The sultan, like the authors of this report, clearly thought only in terms of cash. For Ferdinand the rewards were in Heaven!

An interesting idea, though I’m sure the robustness of the study could be debated (those regression lines do indeed look a bit… jazzy).

Interestingly, a few years ago Spain passed a (temporary) right of return law for those who could prove descent from Jews expelled by the inquisition (which I was eligible for, but it would’ve been legally difficult to satisfy). Some wondered whether this was really an attempt at righting an historic wrong, or an attempt to stimulate the economy even in a relatively minute way.

I theoretically could have been eligible for that, but legally it would have probably been impossible for me, but I always thought exactly the same thing. Win-win for Spain really no matter what.

Persecution need not be solely on a religious basis.One wonders what the effect of the increasing Vaccine Persecution will be. Certainly, another persecuted underclass is being created in the US and globally. Societies always seem to have a demand for scapegoats.

or other methods of exclusion….because of weed, the general antiintellectual, anti-different hegemony in all the places i’ve been(texas and the broader south.), i’ve never felt necessarily at home anywhere.

one gets used to such Ur-Homelessness…and my place is a monument to stubbornness in the face of that manner of being in the world.

this: “…. On average, areas that suffered more from religious persecution are today more religious and less educated, and they exhibit less generalised trust. The adverse impact on output, education, and trust is robust to a wide variety of additional controls.”

my county, and surrounding areas, were settled by the Adelsverein…a society of German Intellectuals and Freethinkers who came way out here specifically to abandon all the strictures and trappings of both religion and monarchy…backwardsness in general, by their words…and try something new: a society built on Reason and Inquiry and Toleration.

it’s all right there in their own words, in all the libraries out this way.

and yet, when descendants of these freethinking folk….the pioneer families in the area, mind you(usually, that get’s you a pass)…tried to erect a granite marker in Comfort Texas to commemorate the history of all this, they were met with a crusade of persecution, rapine and violence…and success in the public courts in removing the monument(google: ‘comfort texas cenotaph).

similarly, one must just generally at least pretend to adhere to the dominant religion in order to be …taken seriously, have a business, etc.

i’ve got an hundred more local-ish anecdotes like that that at the very least calls the authors’ conclusions into question.

my little corner of the Adelsverein….more isolated and therefore clannish than the others….is the picture of cultural inertia, tech inertia…just inertia, in general…the way grandaddy did it, etc.

first job as a cook out here, going on 30 years ago, i made a big pot of real cajun gumbo…my grandma’s recipe…and a redneck ventured into the kitchen to inform me that my “soup” had “oakleaves in it”…and he just couldn’t understand how that could have happened.

of course, they were Bay Leaves,lol.

there are few who remember the Freethinking History of this place…nor one of the only treaties between white folks and red folks that was never broken(until a few years ago, due to the Texas Ranger Museum in Fredericksburg..look it up…a real example of purposeful assholery if ever there was one)

https://medium.com/k%C3%BChner-kommentar/the-kidnapped-monument-to-german-freethinkers-in-the-texas-hill-country-4aee0c1f518c

Well, while giving full credit to the richness of Islamic scholarship, science, art and commercial acumen, let’s not get too warm and gooey over the superior enlightenment and harmonious cosmopolitanism of the Darul Islam as opposed to horrid witch-hunting Christians, and (sigh) wishing that Charles Martel hadn’t stopped them at Poitiers.

The Islamic world, whose economic base remained almost entirely feudal (i.e. involuntary servitude in various forms) across its entire extent for a thousand years (in spite of the popular notion that it was all caravans and dhows and airy domes) has been punctuated by appalling dynastic and sectarian wars and pogroms for that entire time, much like Christendom.

Cordoba itself was originally a refuge for scholars fleeing the Abassid civil wars (yes, that would be Other Muslims). While the collapse of al-Andalus owes as much to infighting among the various Muslim rulers and satraps as it does to Christian resurgence.

Effective and durable central administration lasting more than 1 or 2 rulers is the exception rather than the rule. Especially since the new ruler purges (often fatally) his predecessor’s officials to install his own (semi-loyal) hacks. All it takes is one Omar, Mamoun, Selim or Aurangzeb to undo the good works of their predecessors.

So offsetting gains from commerce and intercourse along the East-West axis (or crescent) of Islam, you get discontinuities of Big Man rule by individuals and their webs of cronies, rather than the continuity of institutions (our much hated Blob). One thousand year long War of the Roses, if you will, while I’m hugely overgeneralizing. :-)

It was only in the mid 1600s that the Ottomans and Persian Safavids began imitating Western nation states and creating durable institutions (unless you count military orders like Mamluks and Janizeri).

Golden ages of widely distributed prosperity, tolerance and open inquiry are rare and transitory in any civilization, and Islam was no exception.

Progress is not in everyone’s interests.

Progress isn’t natural at all, and successful elites will put a halt to it if they can.

Russian Czar’s were very successful, and serfdom still existed in Russia into the early 20th century. The Russian aristocracy wanted for nothing, and there was no reason to change a thing.

“Why Nations Fail” is a good book on how those at the top don’t like progress.

Even in the poorest countries, those at the top are quite happy with the way thing are. You will find they still live in luxury and leisure and everything is working fine for them.

Progress is always a struggle between those below and those at the top.

The Magna Carta represents the triumph of those below, the Barons, over those at the top, the Absolute Monarch, who was quite happy with the way things were. Royalty spent centuries trying to get back the power they had lost with the Magna Carta.

Progress involves wealth and power becoming less concentrated.

Those at the top often like progress in the reverse direction, back to when wealth and power were more concentrated.

The Enlightenment revealed far too much.

Any serious attempt to study the capitalist system always reveals the same inconvenient truth.

Many at the top don’t create any wealth.

The classical economists identified the constructive “earned” income and the parasitic “unearned” income.

Most of the people at the top lived off the parasitic “unearned” income and they now had a big problem.

This problem was solved with neoclassical economics, which hides this distinction.

Our knowledge of banking has been going backwards since 1856.

Credit creation theory -> fractional reserve theory -> financial intermediation theory

“A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence” Richard A. Werner

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

Richard Werner started early as he was In Japan when things went wrong in the 1980s.

Studying their financial crisis he had come to the conclusion banks create money,

He eventually got to prove this empirically at a small bank in Germany.

This seems to have spurred the central banks into action and at long last they revealed the truth.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Let’s not forget about colonization and the persecution of indigenous peoples and their ways all over the world – there is a saying that it takes seven generations to leave that kind of trauma behind.

I think there are even more powerful examples — in how people of color have been treated with segregation, exclusion, and violence in the United States.

The opening comments by Steve et al enocurage me to write the following.

Though the book’s title How not to be Wrong: The Power of Mathematicl Thinking is wrong, it is the only thing wrong in a beautifully written book by Jordan Ellenberg that includes a discussion of things such as linear regression, inference, etc.

Whenever one sees a linear regression just remember – a completly random collection of points has a linear regression – and any data set has a correlation.