Yves here. This study provides a tidy way to respond to moralistic family members and colleagues who are of the “Are there no workhouses?” school of dealing with poverty. One way of being less frontal might be to invoke that great philosopher, Yogi Berra: “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.”1

Of course, the work requirement fans might admit that the point was to limit participation in these programs; the work rule was simply one of many possible ways to achieve that end.

By Colin Gray, Senior Economist, Wayfair: Adam Leive, Assistant Professor, Batten School of Leadership & Public Policy, University of Virginia; Elena Prager, Associate Professor of Strategy, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University; Kelsey Pukelis, Ph.D. student in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School; and Mary Zaki, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics, University of Maryland. Originally published at VoxEU

Proponents of work requirements for social safety net programmes argue that they promote self-sufficiency by encouraging work, while opponents contend that they reduce benefits for the most vulnerable recipients in times of need. This column looks at the impact of the reinstatement of work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the US following a hiatus during the Great Recession. The authors find that work requirements do not appear to improve economic self-sufficiency, while substantially reducing benefits paid to programme recipients.

The US government responded to the Covid-19 pandemic with an unprecedented expansion of the social safety net. This effort is estimated to have kept 17 million people out of poverty in 2020 (Census Bureau 2021, Han et al. 2020). However, the unwinding of these temporary measures has reopened questions about the appropriate generosity of the social safety net.

At the heart of these debates is whether unconditional government aid harms society by discouraging work. Because government resources are finite, policy design must contend with how to best target support to households in times of need. Existing economic research has documented both benefits and costs of government programmes that do not make aid conditional on work (Corman et al. 2018, Dahl and Gielen 2018, Mosley 2021). In the 1990s, economists theoretically analysed how imposing barriers to receiving benefits can have the effect of steering programme dollars to those who benefit the most because they will try the hardest to overcome the barriers (Nichols and Zeckhauser 1982, Besley and Coate 1992). But this conclusion requires certain assumptions that may not hold in practice, such as assuming that the barriers are no higher for low-income people than for high-income people. Until recently, there has been little research testing these assumptions, but recent advances have shown that the assumptions often fail to hold (Deshpande and Li 2019, Homonoff and Somerville forthcoming).

Barriers to benefit receipt often take the form of work requirements, which make benefits conditional on employment. Since 1996, some form of work requirement has existed in many US means-tested programmes. Proponents argue that work requirements promote self-sufficiency by encouraging work (Editorial Board 2021). Opponents contend that the primary effect of work requirements is to reduce benefits for the most vulnerable recipients in times of need (Bernstein and Spielberg 2017).

In new work, we evaluate the competing narratives about the effects of work requirements for receipt of safety net benefits (Gray et al. 2021). We focus on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly known as Food Stamps), which reached 39.9 million Americans in 2020 (USDA 2021). We examine the effect of SNAP’s work requirements on benefit receipt and labour market outcomes when work requirements were reinstated following a multi-year hiatus during the Great Recession.

In SNAP, certain adults are required to work in order to receive benefits for more than a few months. The work requirement can be satisfied by engaging in paid employment, participating in qualifying job training programs, or doing approved community service for at least 80 hours each month. These requirements apply to childless adults who are able-bodied and younger than 50. If they do not meet these requirements, they can only receive benefits for a maximum of three months within a three-year period. The requirements disappear for people aged 50 or older, who do not have time limits on how long they can receive SNAP benefits.

Our research design leveraged this sharp change in time limits at age 50. Our analytic sample included childless adults both younger and older than 50 who were on SNAP in Virginia during the 2009–2013 period, when work requirements were suspended for everyone. When requirements were reinstated in 2013, nothing changed for SNAP recipients who were already 50 or older. Younger recipients, however, now stood to lose their benefits after just a few months unless they met the work requirements. We therefore compared what happened to recipients just under age 50 and just over age 50 following the reinstatement of work requirements until the end of 2015. The difference in outcomes between these groups reveals the effects of the policy.

Critics of work requirements claim that the primary effect of this policy is to take away government assistance from vulnerable people. To evaluate this claim, we examined how many people continued to receive SNAP benefits after work requirements were reinstated. In this and other analyses, we used administrative data from the state of Virginia. The state allowed us to link individuals’ longitudinal SNAP program records to their employment and wage records.

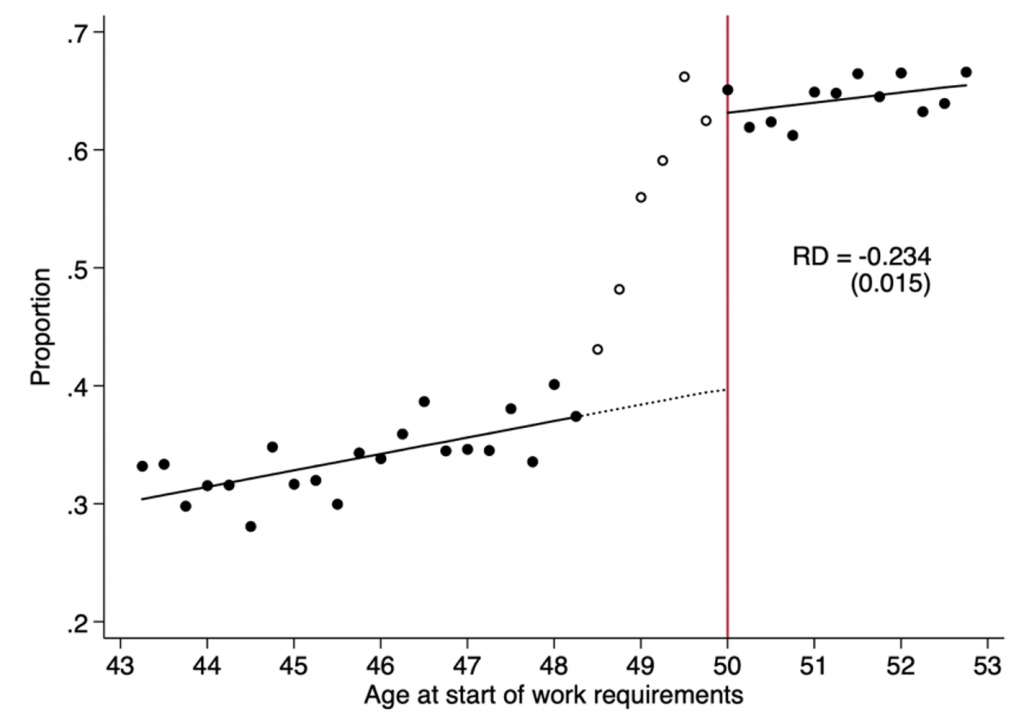

We found that recipients who faced work requirements in 2013 were substantially more likely to leave SNAP within 18 months than their older counterparts who did not face work requirements. Figure 1 displays this result graphically. The vertical axis shows the fraction of recipients still receiving SNAP, as a function of their age when work requirements were reinstated. Among recipients who had just turned 50, 63% were still receiving SNAP benefits 18 months later (solid line to the right of the red vertical line). By contrast, we estimate that fewer than 40% of their counterparts just under age 50 were still receiving benefits at that time (dotted line to the left of the red vertical line).1,2 These results are estimated by analysing only incumbent programme participants. When instead analysing aggregate programme use, we estimate that work requirements reduced the overall number of people receiving benefits by 53%.

Figure 1 Effect of work requirements on receipt of SNAP benefits

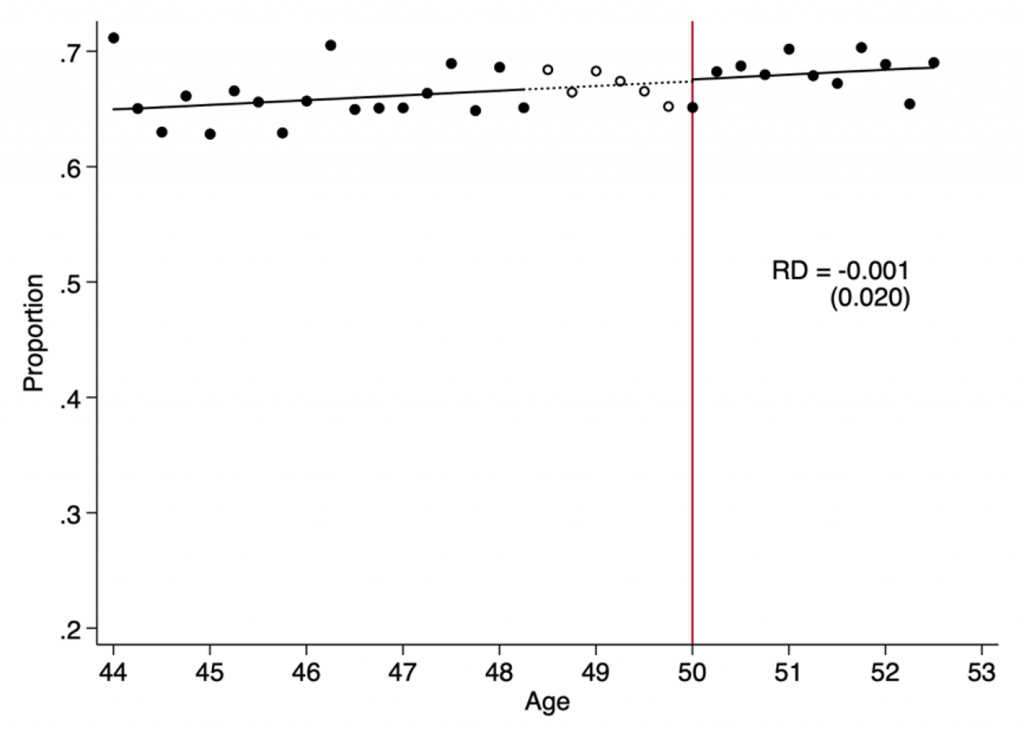

The validity of these estimates would be called into question if recipients who were just under age 50 were substantially different from recipients slightly older than 50. For example, eligibility criteria for disability insurance also loosen at age 50. Receipt of disability benefits changes labour market opportunities and income, and may therefore indirectly affect SNAP utilisation independent of the work requirements. To check whether the large difference in SNAP benefit receipt (see Figure 1) could be explained by such factors, we repeated our analysis using data from 2011 instead of 2013. During this time period, all SNAP recipients were exempt from work requirements regardless of age, so we can measure the differences in benefit receipt around age 50 caused by factors other than work requirements. Figure 2 shows there was no difference in benefit receipt across the age 50 threshold during this time period.3

Figure 2 Placebo test for work requirements

Our findings that work requirements remove government aid from many would-be recipients are exactly the concerns raised by critics of the policy. However, proponents of work requirements would point out that losing benefits may be a good thing for former recipients. The purpose of work requirements is to encourage people to become economically self-sufficient by incentivizing work. It is possible that recipients under age 50 leave SNAP not because they are unable to meet work requirements, but because responding to work requirements causes their employment income to rise above the SNAP eligibility income cut-off. If that is the case, then work requirements could be helpful to both recipients and taxpayers.

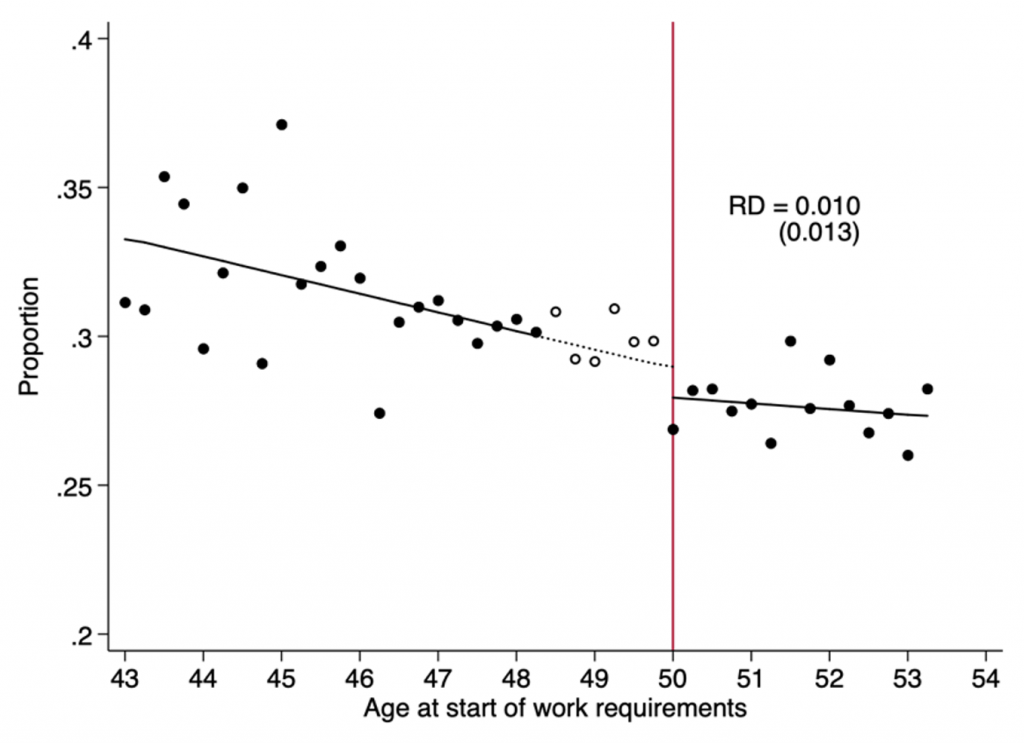

We found little support for this hypothesis. First, our analyses suggest that loss of benefits is disproportionately higher among those recipients under 50 who face the largest barriers to working. Specifically, work requirements cause homeless people to lose benefits at a higher rate than other SNAP recipients.4 Second, we checked directly whether work requirements caused the recipients under 50 to work at higher rates than the older recipients. We found no detectable difference in the fraction of recipients who have jobs on either side of the age 50 threshold. Figure 3 shows this result graphically. In contrast to our findings for benefit receipt, the impact on having a job is either quite small or zero. The only potential improvement in labour market outcomes that we observed was an increase in earnings for a small fraction of recipients near a key income eligibility threshold, but even this result was statistically fragile. In sum, we found little to no effect of SNAP work requirements on economic self-sufficiency, but large negative effects on benefit receipt.

Figure 3 Effect of work requirements on employment

As currently designed, SNAP work requirements do not appear to improve economic self-sufficiency while substantially reducing benefits paid to SNAP recipients. On one hand, this makes work requirements costly to society. On the other hand, work requirements save taxpayers money by reducing the number of people receiving benefits. This sets up a trade-off between savings to taxpayers and harm to would-be SNAP recipients. We analysed this trade-off, accounting for the impact on government budgets.5 The analysis showed that SNAP without work requirements would likely be more effective than other existing programmes at channelling public spending to low-income adults.

Debates are likely to continue regarding the shape and scope of the safety net. In designing off-ramps from the Covid-19 expansions, policymakers should consider the evidence: work requirements do more to remove people from benefits than to bolster employment.

Authors’ note: Mary Zaki is an Assistant Research Professor at the University of Maryland and Financial Economist at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Work on this paper was conducted while Mary Zaki was employed by the University of Maryland. The analysis, conclusions, and opinions set forth here are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or Wayfair.

See original post for references

____

1 It appears Yogi Berra didn’t say this, but it’s so widely attributed to him that for most purposes, it’s not worth cleaning up the origin.

What’s behind the “are there no workhouses?” mindset.

If you are self employed and get to make your own schedule and calendar, you quickly get an earful of how much many of the employed resent their jobs, see it as a kind of hazing, and resent anyone who manages to escape it as not paying their dues.

The amazing thing that is missing from this debate is the importance of intrinsic motivation. People really do *want* to work to some extent and if they aren’t working there is something keeping them from it like degrading work conditions, disability, lack of transportation, or more likely, lack of work.

Intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation has been a big focus of psychology research, filtering into education and human resources but apparently not economics. Here is one study among many.

The idea that one’s economic contribution has to be tied to pay and therefore inequality is good and inevitable is one of the strongest myths of our society. But it is a myth without empirical support. A society where everyone was paid the same could work well.

I’d correct your statement “People really do *want* to work to some extent” to “People usually want to contribute to something tangible and constructive”.

Service work is largely unsatisfying because there’s no visible cumulative result. Ditto screwing wheels on cars… but assembling much more of a car is much better.

Before our society became so exploitative, there were many happy cashiers, restaurant servers, secretaries, etc. I remember that world from my childhood and my parents remember it from working in it.

So I stand by my statement. Work is its own reward if it is not exploitative or demeaning, which it overwhelmingly is now in the US.

I am self employed, work from home, and have sometimes fantasized about taking a part time job just to get out of the house except I know how all workers are treated now.

On your last para… I heard that British PMC in the 1950’s and 60’s, so high street bankers, doctors etc used to not live long on retirement because their “self” was so oriented on their previous position that they had nothing to do.

I always ask my “They’re too lazy to work hard” relatives and acquaintances (many of whom are Dems) there three questions:

Do you want to hire these people?

Do you want to work with these people?

Would you want to be their customer?

I firmly believe that some people just shouldn’t be in the work force, and that we should provide these people an income without any shaming. Maybe their contribution to the economy is creating demand and caring for those that need it.

Plenty of people were born to work anonymously and quietly on a shop floor and they would have been happy in decades past before all those jobs got shipped to low wage countries.

Work= 1099, our gig serfdom. Devoid: ACA health insurance, sick leave, Social Security, Medicare or income tax withholding, OSHA mandated PPE, HVAC or protocols, any SAY in any capricious choice of duties, schedule or remuneration. “Essential,” was the new Black, as scores-of-thousands were forced to work, infecting loved-ones, co-workers, commuters, teachers, healthcare & first-responders… NASDAQ equities BOOMED during catastrophe capitalism’s FIRE & PHARMA feeding frenzy. I’m not saying this business model was given that much thought. But, none of this hasn’t been recorded, during previous “disruptive” plagues? Narziß und Goldmund & La Peste come to mind?

If we had a jobs guarantee program it would solve the whole stigma. It would provide everyone who needed one a job, at a decent wage. It would not interfere with entitlements for older and less able people, etc.

I guess I wonder why an economic study with scatter plots is needed to conclude: “… work requirements do not appear to improve economic self-sufficiency, while substantially reducing benefits paid to program recipients.”

As I recall, the SNAP-type programs were introduced at a time following the successful consolidation of u.s. Agriculture when excess agricultural production impacted agricultural price supports. I thought the purpose for the SNAP program was partly an effort find a better use of Big Ag’s excess produce than dumping it. Feeding children and the poor was a nice selling point for the program. Is it too cynical to suggest that the work requirements are introduced as a way to throttle back the program now that foreign markets have been ‘adjusted’ by Globalization to absorb a larger share of our farm produce.