Yves here. Classic studies by David Card and Alan Krueger on the impact of minimum wage increases on the income and employment levels of fast food workers came to similar conclusions as this paper: increasing minimum wages does not in fact produce unemployment, and so winds up in a net increase in the income of low wage workers. From Vox after Krueger committed suicide:

In introductory economics courses, students are typically taught that setting price floors — on milk, oil, or, perhaps most importantly, labor — causes supply to exceed demand.

In the case of labor, what that means is that if there’s a minimum wage, employers’ demand for workers falls (because they cost more), and the supply of workers increases (because they’re promised more money), meaning there’s unemployment, with all the costs and suffering that entails.

This conclusion was largely based on abstract theory, but it held sway for decades….

In a paper first published by the National Bureau of Economic Researchin 1993, Krueger and his co-author Card exploded that conventional wisdom. They sought to evaluate the effects of an increase in New Jersey’s minimum wage, from $4.25 to $5.05 an hour, that took effect on April 1, 1992. (At 2019 prices, that’s equivalent to a hike from $7.70 to $9.15.)

Card and Krueger surveyed more than 400 fast-food restaurants in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania to see if employment growth was slower in New Jersey following the minimum wage increase. They found no evidence that it was. “Despite the increase in wages, full-time-equivalent employment increased in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania,” they concluded. That increase wasn’t statistically significant, but they certainly found no reason to think that the minimum wage was hurting job growth in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania.

Card and Krueger’s was not the first paper to estimate the empirical effects of the minimum wage. But its compelling methodology, and the fact that it came from two highly respected professors at Princeton, forced orthodox economists to take the conclusion seriously. New York Times reporter Binyamin Appelbaum lays out some of the vitriolic reaction to the paper in a Twitter thread:

The Nobel laureate James Buchanan wrote in the Wall Street Journal that Card and Krueger were undermining the credibility of economics as a discipline. He called them and their allies “a bevy of camp-following whores.”

— Binyamin Appelbaum (@BCAppelbaum) March 18, 2019

Card and Krueger expanded their results into a well-regarded book, Myth and Measurement, and then largely left the debate. “I’ve subsequently stayed away from the minimum wage literature for a number of reasons,” Card said in an interview years later. “First, it cost me a lot of friends. People that I had known for many years, for instance, some of the ones I met at my first job at the University of Chicago, became very angry or disappointed. They thought that in publishing our work we were being traitors to the cause of economics as a whole.”

Now to the study from Germany, which adds a new finding on company performance.

By Christian Dustmann, Professor of Economics, University College London and Director of the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration; Attila Lindner, Assistant Professor, University College London; Uta Schӧnberg, Professor of Economics, University College London; Matthias Umkehrer, Researcher, Federal Employment Agency, Institute for Employment Research; and Philipp vom Berge, Deputy Head, Research Data Center of the Federal Employment Agency, Institute for Employment Research. Originally published at VoxEU

In January 2015, Germany introduced a uniform minimum wage of €8.50. Many economists and media outlets predicted that this would have dire consequences for the German economy and result in substantial job losses. This column shows that, in fact, the introduction of the minimum wage boosted pay for low-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects. It also prompted a reallocation of staff towards more productive firms. Overall, the minimum wage helped reduce wage inequality while improving the quality of firms operating in the economy.

Germany introduced a minimum wage in January 2015, setting it at a uniform national level of €8.50. The minimum wage cut deep into the wage distribution, with 15% of workers having earned an hourly wage below €8.50 six months before the minimum wage came into effect. The reform was triggered by falling wages at the bottom of the wage distribution (Dustmann et al. 2009, Marin 2010) and the dwindling importance of trade unions (Dustmann et al. 2014). In the period leading up to its introduction, the minimum wage was viewed critically by many economists and segments of the media (Sachverständigenrat 2013, Der Spiegel 2013, FAZ 2013, Die Welt 2013), with two early studies predicting that it would cause up to 900,000 job losses (Knabe et al. 2014, Müller and Steiner 2013).

Our analysis (Dustmann et al. 2021) shows that the minimum wage significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects. The lack of employment responses, however, masks some important structural shifts in the labour market. Specifically, we show that the minimum wage led to a reallocation of workers from smaller to larger establishments, from lower-paying to higher-paying establishments, and from less to more productive establishments, thereby helping to improve the quality of establishments operating in the economy.

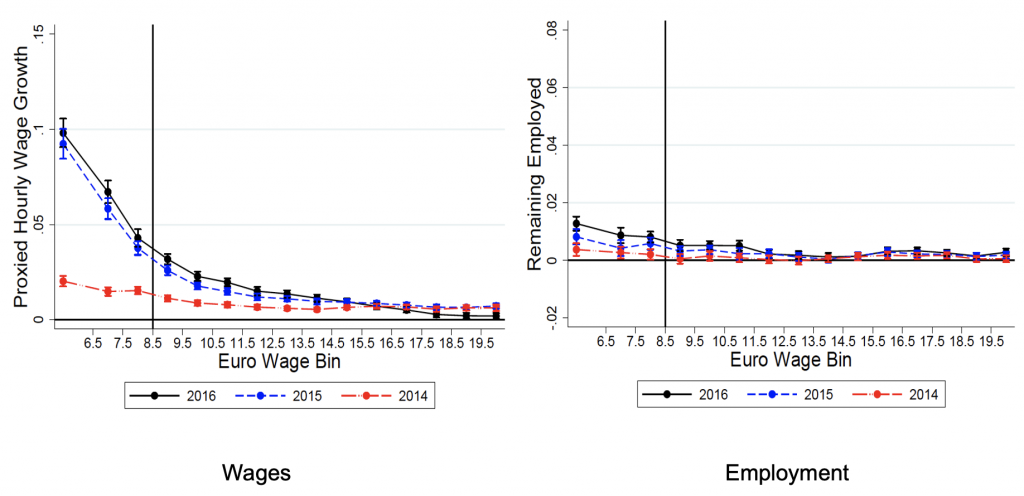

The Effect of the Minimum Wage on Wages and Employment

To examine the labour market effects of Germany’s first-time introduction of the minimum wage, we follow individuals over time and contrast individual wage growth and employment changes in periods before the introduction of the minimum wage to those after. The analysis finds that the minimum wage significantly increased wages of low-wage workers. This is illustrated in the left panel of Figure 1, which plots the two-year excess wage growth by initial wage bin (horizontal axis) in the periods 2012 versus 2014 to 2014 versus 2016 against the 2011 versus 2013 pre-policy period, controlling for individual characteristics. The figure clearly highlights that hourly wage growth in the post-policy periods considerably surpasses hourly wage growth over the 2011 to 2013 period for wage bins below the hourly minimum wage of €8.50. Moreover, wage growth also exceeds pre-policy (2011 versus 2013) hourly wage growth for wage bins slightly above the minimum wage, in line with spillover effects of the minimum wage to higher wage bins. In contrast, wage growth for wage bins higher than €12.50 has not been affected by the introduction of the minimum wage.

The right panel of Figure 1 illustrates that there is no indication that the introduction of the minimum wage lowered employment prospects of low-wage workers. Workers directly exposed to the minimum wage (earning less than €8.50 per hour at baseline) are even slightly more likely to remain employed after (i.e. in 2015 and 2016) than before (i.e. in 2013) the introduction of the minimum wage. The small positive employment effects are consistent with the idea that wage increases induced by the minimum wage has made employment a more attractive option for low-wage workers.

In summary, this analysis follows individuals’ wages and employment status over time, and shows that the minimum wage raised wages for minimum-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects. In consequence, the minimum wage policy reduced wage inequality, as intended.

Figure 1 Wage and employment effects of the minimum wage: Individual approach

Notes: The left panel plots two-year excess wage growth by initial wage bin in the periods 2012 vs 2014 to 2014 vs 2016 relative to the 2011 vs 2013 pre-policy period. The right panel plots the probability that an employed worker is employed two years later against her initial wage bin for the periods 2012 vs 2014 to 2014 vs 2016 relative to the 2011 vs 2013 pre-policy period. Underlying regressions control for individual characteristics at baseline.

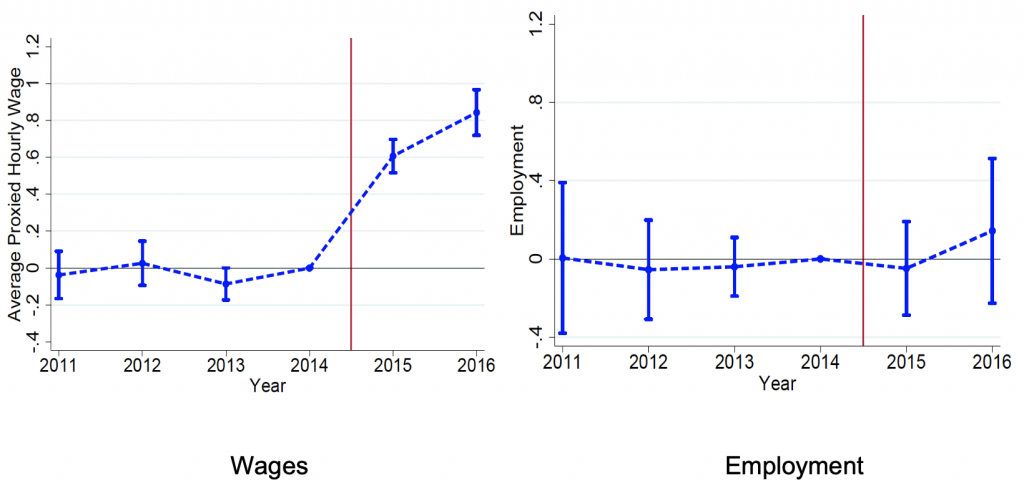

In a next step, we exploit the considerable variation in the exposure to the minimum wage across 401 local areas in Germany, by tracing how (log) local average hourly wages and (log) local employment evolve in districts (‘Kreis’) differentially exposed to the minimum wage, due to differences in pre-policy local wage levels (see Ahlfeld et al. 2018 for a related analysis that uses variation in the minimum-wage bite across regions in Germany). The left panel of Figure 2 shows that relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend, wage growth in highly affected districts strongly picks up relative to wage growth in less affected districts after the introduction of the minimum wage. The right panel of Figure 2 provides a corresponding analysis for the employment effects of the minimum wage and illustrates that the minimum wage had no discernible impact on local employment, in line with our findings from the individual analysis.

Figure 2 Wage and employment effects of the minimum wage: Regional approach

Notes: The panels show how log local average hourly wages (left panel) and log local employment (right panel) evolve in regions differentially exposed to the minimum wage, relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend.

Adjustment of the Labour Market to the Minimum Wage Introduction

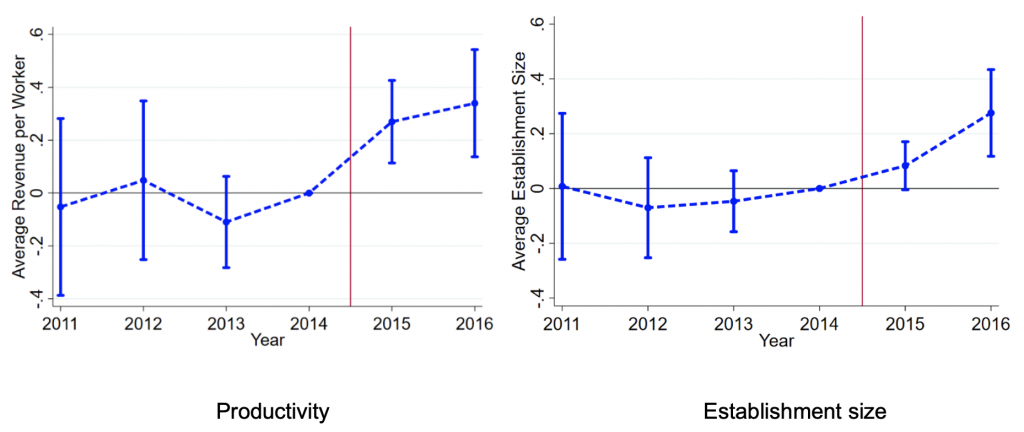

The absence of an employment response, despite a strong wage response, potentially masks structural shifts in the labour market, such as the exit of low-productivity establishments from the market and a shift in employment toward more productive establishments. We present evidence consistent with reallocation at both the individual and regional level. At the individual level, we show that after the introduction of the minimum wage, low-wage workers – but not high-wage workers – are more likely to upgrade to establishments that pay higher wages on average, offer more full-time and more stable employment relationships, pay higher wage premiums to the same type of worker, are larger, and are more productive (as measured by their predicted revenues per worker).

At the regional level, we show that after the introduction of the minimum wage, the quality of establishments improved in local areas highly exposed to the minimum wage, an effect that is driven by the reallocation of workers to more productive establishments within the local area. Figures 3 illustrates this point in terms of productivity (left panel) and average establishment size (right panel), both of which strongly increase in areas heavily exposed to the minimum wage after the introduction of the reform, relative to less exposed areas and 2011–2014 pre-policy trends. In a similar vein, we show that the minimum wage induced some small businesses with fewer than three employees to exit the market, signalling a shift toward establishments that pay higher wage premiums to the same type of worker in more- relative to less-exposed areas.

Figure 3 Reallocation effects of the minimum wage: Regional approach

Notes: The panels show how (predicted) log mean revenue per worker (left panel) and log mean establishment size (right panel) evolve in regions differentially exposed to the minimum wage, relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the concerns among many economists that the introduction of the minimum wage in Germany in 2015 would cause substantial job losses were unfounded. Rather, we show that the introduction of the minimum wage boosted wages of low-wage workers, did not lower employment, and induced a reallocation toward more productive establishments. As such, the minimum wage has helped to reduce wage inequality, across workers and local areas. These results do not imply that no establishments or workers lost out as a result of the introduction of the minimum wage. For example, the minimum wage caused some small businesses to exit the market. Moreover, the reallocation of low-wage workers to higher paying establishments came at the expense of increased commuting time, which might have left some workers worse off despite earning a higher wage. Nevertheless, even though there might be some losers from the minimum wage policy, we conclude that the overall welfare of low-wage workers likely increased in response to the introduction of the minimum wage.

See original post for references

‘The Nobel laureate James Buchanan wrote in the Wall Street Journal that Card and Krueger were undermining the credibility of economics as a discipline. He called them and their allies “a bevy of camp-following whores.” ‘

Yeah, I can fully believe that he said something like that-

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2018/05/meet-economist-behind-one-percents-stealth-takeover-america.html

he won a fake nobel. and if these frauds running the pulitzer, nobel and other prize givers are not run out of those organizations, they will be viewed as shills, and destroyed in the eyes of civil society.

buchanan should have been given the prize for advancing fascism. a long walk off of a short dock.

When Buchanan says “discipline”, he means economics as a *discipline*ary tool for the rabble, to preserve inequity.

Buchanan and his ilk are jealous palace concubines.

That’s a fascinating piece of history, Yves. I can understand someone like Buchanan more easily now that I’ve been exposed to another piece of the context. The second “semester” of my Common Earth course does a quick tour of neoliberalism before moving to Kelton’s The Deficit Myth. To give us some historical context, we were introduced to the illustrated version of The Road to Serfdom. Suffice it to say that its argument is not exactly understated. My response in class was that when you connect the workplace and firing squads, my mind moves to Joe Hill, a victim of the capitalist mine owners, not the “planners.”

It does remind us that one of the underlying aspects of neoliberalism is “the businessman decides.” Not the state. Certainly not the people. Not bureaucrats or planners. Businessmen. So we can look around and see what happens when business persons make all the important decisions about how a society will be structured, what projects it will undertake, what risks it will accept, etc. It doesn’t seem to be working out all that well.

Wasn’t it in the Eighties that the complaint “politicians have never run a business” really took off?

“Elect me because I’ve run a business and know how the world works.”

I wish the authors had been clearer about the fundamental economic (theory) point made by the analysis, which has been demonstrated over and over again by history (even if that history is studiously avoided by mainstream economists): conventional economic theory assumes that workers are paid (more or less) in line with their productivity – what their work is “worth” – so that raising their wages will lead to unemployment because employers won’t pay people more than the value of what they produce. But the record of the last hundred years shows this is inaccurate in two fundamental ways:

1. Power disparities mean that many, probably most, working people are paid less than the value of what they produce, and so raising wages does not lead to unemployment because employers are still net better off (i.e. make more money) by having to pay workers a bit more rather than firing them and shrinking the business. To the extent workers are paid closer to (or, in the case of our overlords, much more than) the value of what they produce, it is due to explicit institutional arrangements (strong unions and worker-friendly gov’ts for working people; social mores and class solidarity for the overlords), not any magic of the market.

2. The (dynamic) evidence over time shows that raising wages leads to productivity growth, not the other way around. This was conventional wisdom 75 years ago and is still admitted by the occasional labor economist, just not loud enough to ruffle any mainstream feathers, lest one get the Krueger treatment.

If profits are being taken by a company and distributed to shareholders, it would seem that by definition all the working people in that company are being paid less than what they are worth.

And if a company is not profitable, the first place I’d look is at bloated management salaries. How many multimillionaires and billionaires have the likes of Uber, etc. minted even as they set cash on fire?

lyman,

You missed the bit where a firm owns assets. Whether it is physical assets, intellectual property, or intangible assets. They also take on RISK. If I pay a bunch of virologists to develop a vaccine I need capital and I am taking on risk that they might not succeed. My profits come from the success, skill and productivity of SOME of my virologists. The profit comes from my capital invested and the risks I took.

(Picking pharmaceuticals probably wasn’t the best example because they are no shining beacon of ethical capitalism. But I hope you get the point.)

Sorry, but having an idea, borrowing other people’s money, and then getting others to do the work is not well, work. Not by my definition at least.

I really dislike this idea that risk should be remunerated, often to excess, by those in the C suites who made a decision. That didn’t take much work either. And by making those decisions were they risking their own money from their own bank account, or were they maybe risking someone;s pension instead? And don’t workers take on risk too every day they show up for work for a company that might not pay them for their wages? Or cheat them out of their fair share?

I think it is completely possible to have a company that does not have owners where all the people who work there share equally in any “risk” and financial gain.

One way of looking at things is that if a company turns a profit after paying everybody who works there a decent salary, then they’ve charged the rest of society too much for their goods and services.

Thank you lyman alpha blob, I was stressing over how much work it would be to correct all of “Mark” the sock puppet’s mistakes, and you did it with no effort at all.

As a mining engineer in Zambia some 20 years ago I was put in charge of part of the underground mine were the development miners were working 9 hours a day 7 days per week for months. They were using hand held rotary hammer drills weighing about 60 pounds and the productivity was very low. I immediately enforced 6 day a week working and the productivity increased so much that the distance developed in the first month, with 4 less working days, was higher than when working 7 days per week.

The Chinese were trying to increase internal consumption, but they were using neoclassical economics.

Davos 2019 – The Chinese have now realised high housing costs eat into consumer spending and they wanted to increase internal consumption.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MNBcIFu-_V0

They let real estate rip and have now realised why that wasn’t a good idea.

The equation makes it so easy.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

The cost of living term goes up with increased housing costs.

The disposable income term goes down.

They didn’t have the equation, they used neoclassical economics.

The Chinese had to learn the hard way and it took years, but they got there in the end.

Why is neoclassical economics like that?

The early neoclassical economists hid the problems of rentier activity in the economy by removing the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income and they conflated “land” with “capital”.

They took the focus off the cost of living that had been so important to the Classical Economists as this is where rentier activity in the economy shows up.

It’s so well hidden that everyone trips up over the cost of living, even the Chinese.

What does the equation do?

The equation puts the rentiers back into the picture, who had been removed by the early neoclassical economists.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees want more disposable income

Employers want to maximise profit by keeping wages as low as possible

The rentiers gains push up the cost of living.

Governments push up taxes to gain more revenue.

What is the minimum wage?

Let’s set disposable income to zero.

The minimum wage = taxes + the cost of living

As housing costs rise, we drive up the minimum wage.

That sounds like economics is a not science but a religion.

In an earlier life I naively entered economics thinking it was a science. I left as I became disillusioned when I realised just how closed minded most academic orthodoxy was.

I’m an engineer now. I build plants and equipment that process food. I can sleep better at night knowing that I’m actually doing something productive that the world needs.

(The world also needs good economists. But it does seem that economics often doesn’t WANT good economists.)

That account of ostracizing is breathtaking. Proper science is “when the facts change, I change my mind”. Card and Krueger didn’t just have ‘heretical’ thoughts; they brought along a substantial body of evidence. And the reaction of many of their colleagues wasn’t to consider that the conventional understanding had been in error, instead it was to throw a giant hissy fit and socially shun Card and Krueger. Whatever their pretensions, they weren’t behaving like scientists. They were behaving like Jehovah’s Witnesses.

I would think poor old common sense, so often misled, would nevertheless say that increasing the minimum wage would increase, not decrease, employment, at least in a situation where there were a substantial number of workers employed at the minimum wage. Their incomes would rise, given them money to spend, which they would be likely to do because they would be likely to be living hand to mouth, and so they would spend it, increasing business, and thus an immediate need for additional employees. This would work at least for small-to-modest increases. Inflation, not unemployment, would follow, but would lag by a few months to a few years because it would take time to bid up prices.

In view of this theory, I examined the changes in minimum wage levels in various places, long with employment, average wages, prices, interest, etc. etc., using some crude signal-processing math I had at hand, but I regret to say I could not find any significant correlation. I think this means the signal, if any, was drowned by the noise of competing influences on employment and so forth, or that I didn’t know what I was doing, also a possibility.

This enraged the libbits I was discussing the question with because I used numbers and empirical evidence as described above.

It is astonishing to me that it seems to have taken Card and Krueger and the economics industry, a long time to figure this out, when I, without training or study, did it in an afternoon. Poor common sense, a wallflower as ever! Well, that’s what happens when you’re not the prettiest girl at the party.

Incidentally, none of the reasoning above is likely to work when the predominant form of currency is funny money, as seems to be the case at present. ‘Enraging the libbits’ is a pastime from yesteryear.

Higher min wage can make more (low wage) jobs

Imagine a world where buying consumer goods takes place only on Mon-Tue-Wed-Thur-Fri — and — cashing pay checks done only on Sat-Sun. (I just viewed Dark City, so I am in the mood for such a model.)

Typical employers like Target and Walgreens average 12.5% labor costs — outliers WalMart and fast food have 7% and 25% labor costs. Say, in one-single Mon-thru-Fri week, lower 40% pay employees double wages on average — up 50% at fast food, up 2 1/2 X at Walmart.

Consumer prices for goods produced by lower income workers have to rise about 12.5% across the board — demand falls 12.5% for lower pay produced goods …

… on that particular Mon-thru-Fri.

Sat comes; lower cost workers pick up their doubled pay — for producing possibly fewer goods — Mon-thru-Fri haven’t dawned yet.

Mon comes; lower pay workers take the extra money squeezed from consumers to market to purchase goods and services — probably proportionately more on goods produced by lower wage workers. Demand for lower pay produced goods rises more than 12.5%.

****************************

Put this eight-grade, market math to work for everybody whose labor the consumer might agree is worth more:

https://onlabor.org/why-not-hold-union-representation-elections-on-a-regular-schedule/

I have long believed that the minimum wage is kept low in order to make the military an attractive option for young people.

We need an economy that over a decade creates 100 million people making $100,000/year. Instead we think creating 10 million people making $1,000,000/year over a decade is the measure of success.

NOT!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Another massive “allocation effect” is that under a regime of having flat or regressive income taxation, company managers loot the companies and pay themselves- because they can keep it.

The core truth is that executives really do not care about salary- they care about status. In The Olde Dayes, big corporations gave out visible status symbols. Executive perks were a small salary bump and then subsidized services for prestige- company car, country club membership, the annual convention, etc. The movie “How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying” is a great portrait of this culture. And fun!

A point not often remarked on is that places with low (minimum) wages are poor. People have to work two jobs and a gig to survive. Raise the minimum wage and they can have a life, and spend the additional money, often in places that employ minimum wage workers.

Setting the minimum wage at a reasonable fraction of the median wage (1/2 or 2/3) is reasonable.