This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 929 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year,, and our current goal, expanding our reach.

Yves here. It is no doubt obvious to those who understand that this inflation isn’t the result of excess demand but shortages, supply chain disruption, and Covid reducing the size of the workforce, now compounded by sanctions blowback greatly increasing inflationary pressures through energy and other commodity price increases. So this latest development, demand destruction in gasoline, which is likely being paralleled by a contraction in demand for leisure and travel, is occurring even as overall inflation rises. The Fed will have to do considerable harm to lower demand enough to counteract the fundamentals driving this inflation.

By Wolf Richter. Originally published at Wolf Street

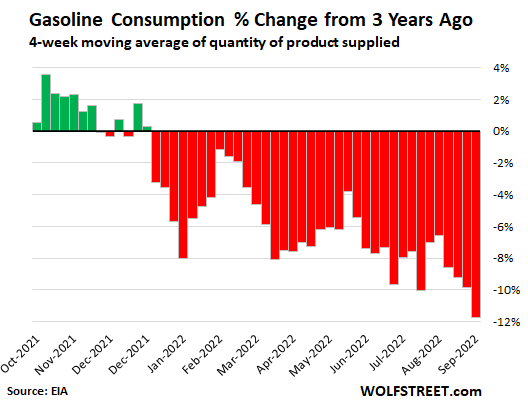

Over the four weeks through September 9, gasoline consumption dropped by 11.7% from the same four-week period in 2019, to 8.56 million barrels per day on average, below the same periods in 2020 and 2021, according to EIA data today.

The EIA measures gasoline consumption in terms of barrels supplied to the market by refiners, blenders, etc., and not by retail sales at gas stations. On this moving four-week average basis, it was the steepest decline so far this year, that has seen nothing but declines from the same periods in 2019.

The decline accelerated even as gasoline prices have plunged from the top of the spike in mid-June. This may indicate that the classic economic principle of “demand destruction” – where a price spike triggers a decline in demand that then causes the price to back off – may not just be a blip, but that this demand destruction may have become in part structural.

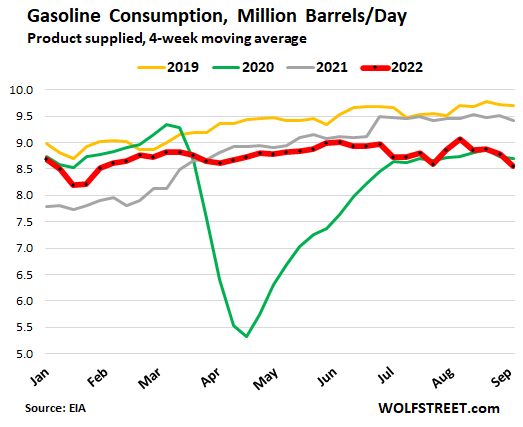

Peak driving season is in the summer. But this year, gasoline demand in the summer (red line in the chart below) was substantially below the summer driving season in 2019 (yellow line) and in 2021 (gray line), and roughly even with the beaten-down levels of 2020 (green line). And then in August and September, demand fell further, and ended below the levels of 2020:

This demand destruction caused by sky-high gasoline prices is happening on a global scale. It’s where price resistance has set in, and people have changed their behavior a little here and there. They cut out unnecessary trips. They’re prioritizing their most fuel-efficient vehicle in the garage. When they buy a vehicle, fuel economy is moving up as a decision factor. Working from home has become sticky, and fewer people are commuting to work every day. And for vacations, people might have chosen to go places that involve less driving.

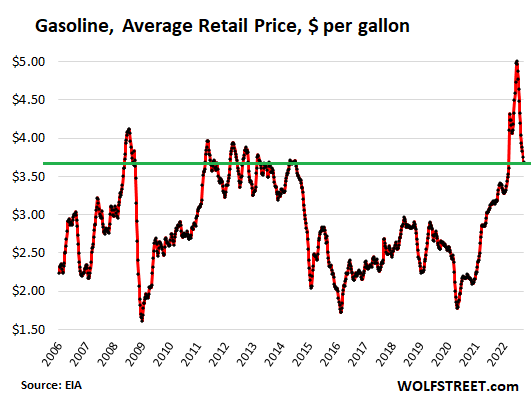

Demand Destruction Pushed Down the Price

The average price of gasoline in the US, all grades combined, had spiked to $5.00 a gallon by June 13, according to EIA data. This type of price spike – up 63% year-over-year – sent shock waves through wallets and minds. Everyone was talking about the price of gasoline. But the average price has now dropped to $3.69, which is where it had been for years in the past – and yet, demand destruction accelerated:

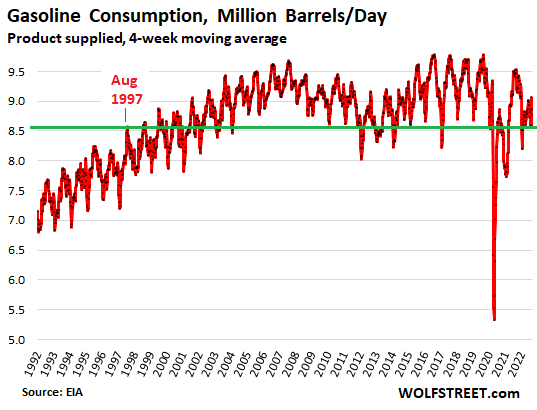

Gasoline Consumption Has Been Stagnant Since 2007.

Over the long term, the four-week average gasoline consumption of 8.56 million barrels per day was first exceeded in August 1997:

EVs are still only a minuscule part of the 284 million vehicles in operation. There are only 1.8 million EVs on the road, for a minuscule share of 0.63% of all vehicles in operation (my discussion on what Americans are driving). EVs are being prioritized for driving in two-vehicle households to dodge high gasoline prices. And EV sales are booming, with long wait lists and consumers willing to pay whatever. So EVs are starting to have some impact on gasoline demand, but it’s still very small.

Improvements in fuel-efficiency across the spectrum over the past 20 years have largely been responsible for the stagnation in demand through 2019.

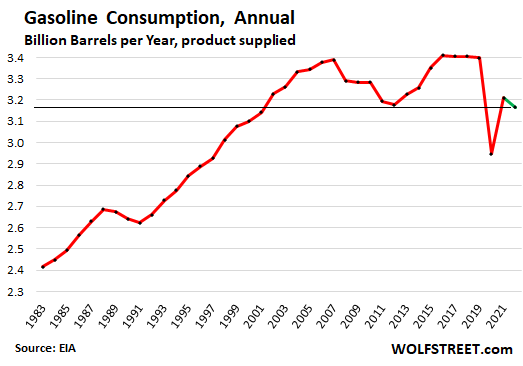

On an annual basis, gasoline consumption hit a ceiling in the year 2007 at about 3.4 billion barrels per year, and re-hit that same ceiling in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019, with a big trough from 2008 through 2015, and then another trough, but deeper, in 2020 and 2021.

Consumption this year is shaping up to be below 2021. There is a good chance that gasoline consumption may never again hit that ceiling of 3.4 billion barrels per year again (green = my estimate for 2022):

Refineries Have Long Seen This Demand Trend

If US refiners have not been investing in the construction of new refineries, it’s because they too have long seen this long-term stagnation and now decline in the demand for gasoline.

Rather than relying on growth in the US, refineries turned into big exporters of gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other petroleum products. Even the refineries in the San Francisco Bay Area are importing crude oil and are exporting refined product to Mexico and further south.

We here in San Francisco could see those tankers head out the Golden Gate fully loaded, while we paid over $6 a gallon, and there is nothing like putting $100 into a tank every two weeks to persuade someone to look for alternatives.

Which – following the principle of demand destruction – caused sales of EVs to soar to a share of 15% of all new vehicles sold in California in the first half of this year, from a share of 9.5% in 2021 and 6.2% in 2020.

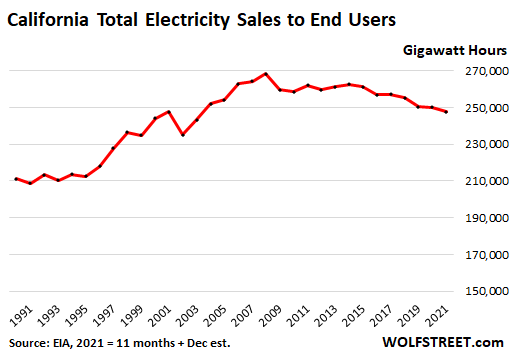

In the middle of the night, electric utilities sit on huge amounts of idle and very costly capacity, and this is when EV owners are encouraged to charge their vehicles because electricity prices are lower and people with garages can just plug them in overnight. Utilities are licking their chops because they too, like refiners, have been stuck in a stagnating business, as consumers, businesses, and municipalities have invested in more efficient lights, appliances, HVAC systems, and equipment.

And those utilities, by selling electricity to EV owners in the middle of the night, are making money off what was their costly idle capacity, and someday this might even get their business to grow again, which would be a godsend for them, but there were still no signs of growth in electricity sales:

I have been comparing with Spanish data and there is somehow a different pattern in Spain in the latest years. I compared gasoline US consumption with diesel consumption in Spain (diesel takes the role of gasoline here). Looking at moving annual consumption, as per the graph before the last one, in the US, the after Covid recovery is not total and never resumes to pre-Covid levels whereas In Spain, you see total post-Covid recovery to levels a little bit higher than pre-Covid in 2022. This suggests more durable Covid impact in the US than in Spain. Regarding the magnitude of the impact, it was only slightly higher in the US (a loss of about 13,2% in consumption from 2019 peak to Covid valley against a loss of 12,6% in Spain in the same period.

Why is it? More people in the US decided to stay working from home?

> More people in the US decided to stay working from home?

There’s also, per items linked at NC in recent days (I don’t have links handy) a significant number of people not returning to work due to COVID sequelae; IIRC the number reported was in the range 2-4 millions. To the extent that these had previously been commuting to work in their own vehicles, this may be a progressively growing brake on fuel demand.

(this point is also made by thoughtfulperson below @7:35, which appeared after I started this comment.)

Post-coronavirus public transport aversion!

In the UK, the number of train and bus commuters who have switched to driving for their occasional commute plus home working is huge. And the towns are largely empty of traffic still so this is not exiguous.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the existing public transport provision continues (the trains and buses have to run to the timetable) so public transport fuel demand is incompressible (at extreme fuel prices or extreme passenger boycotts like Q2 2020,, demand may fall more sharply as the network is turned off…)

Europe had high public transport share of journeys. The car is substituting for public transport in Europe so the increase in private mileage adds fuel demand in Europe whereas in the US the pure-car model shows only price-driven demand destruction (possibly among the poorest, who are still on public transport in Europe).

Dont worry though, Davis man has a plan. You will own nothing and be happy: we will all be back on the bus if the fuel prices dont go down….

Oh the irony, that the west mounts its push bike and its electric trolleybus while the evil communists petrolheads tool around in the cars.

I wrote a comment but skynet ate it.

A much condensed version: commuters are averse to public transport mis-pandemic and drive in when they work from the office (because traffic levels are still down). In the US, this was the status qui ante in Europe, we had a lot of public transport. So the switch makes Europe look like demand is crowing. EU and US public transport fuel demand will not go down to balance because the syste m has to run in full for even low passenger numbers).

I think this is part of the answer….

If there are 1 million workers out with long covid, they are not commuting. Add in EVs and use of more fuel efficient vehicles due to high prices. Plus more working from home (certainly compared to pre pandemic). Thus the drop in the usa seems reasonable?

There are definitely fewer commuters on the road these days. I live on the edge of a suburban village near a traffic light and the high school. Pre-covid, on the worst evenings traffic could back up a mile down the road as commuters navigated the light and the left turn traffic going to the HS. I haven’t seen it back up more than maybe a 1/4 mile in the past 2 years.

I can also personal say my wife and I swapped cars because I work from home 2 days a week and she drives many more miles for her job than I do. Now she’s driving the more fuel efficient car.

While not related to gasoline sales, but would definitely translate into lower diesel consumption… because of the difficulty in finding bus drivers our district has upped the distance where students are required to walk to school and virtually eliminated individual home pick-up – most youth riding the bus have community pick-up spots. My assumption is that this is to speed-up route times so that they can turn buses around faster thereby reducing the number of busses (and bus drivers) needed to get kids to school. It should also translate into less diesel consumed.

Our Prius is nine years old and I’d set a limit on reselling it at 10, old enough to have gotten plenty of use out of it and still in good enough shape for resale, but alot a has happened in nine years and now maybe we hold onto it for an extra year.

Pre-Covid I might have seen three Tesla’s on the road. Now they seem to be everywhere, and some Toyota hybrid SUV I haven’t identified yet. Also solar panels on roofs, once rare now increasingly more common in every neighborhood.

The price of gasoline briefly exceeded $4 a gallon this summer but for the most part has stayed below $4, yet traffic was gloriously sparse and the stores were quiet with few customers. As for that I reasoned that given the heat, customers had just decided to stay home more, or bundle their errands for completing in the cooler temps of early morning and evening.

This is a university town, schools are back in session, and the daily temps are much cooler. Yesterday I was driving mid-day grumbling about the traffic. It seemed worse that ever!

My late model Elantra which is not their smallest car or engine gets over 40 mpg on the highway due to its “Atkinson cycle” engine (same type as on the Prius) and 6 speed transmission. Long ago when I had a Volkswagen–a tiny tin can by comparison–it got maybe 27 mpg max. Newer cars than mine use the somewhat controversial CVT transmission to further smooth out engine rpm to the maximum efficiency level. These changes do tend to suppress the hot rod potential of these cars so car makers have been moving in a practical direction compared to the old days or perhaps are only doing so to justify their high margin trucks and SUVs.

But the efficiency improvements due to weight savings and engine tweaking may have reached their limit and driving less or not at all may be the way forward. In the last couple of years my town has brought in rental electric scooters such as those that clog big city (San Francisco) sidewalks and perhaps we will be zipping around on those. They do seem more popular than the preceding and now gone bicycle rentals. Me, I still bike on the town’s expanding network of trails.

I get 40+ MPG with my 2016 Golf (1.8t) easily on a modest run by keeping to 75MPH max. No electric motors involved. 6 speed auto.

And I’ll never buy a car with a CVT – they don’t last anywhere near as long as manual or auto.

Seen anyone over the age of 40 on those scooters yet? Here… not so much. Seems to be mostly for the young, the lean, the cool… the better able to heal from broken bones, sprains, road rashes, and maybe loss of face.

By “scooters” I assume you mean “e-scooters”? Or “app-scooters”? Or whatever we want to call them?

I would like to see e-scooters evolve towards user-safety the same way the bicycle evolved towards user-safety over time. The bicycle started out as the giant front-wheel dare-devil life-in-your-hands danger bicycle and evolved over time to the safety bicycle we know today.

In a similar way, the dare-devil life-in-your-hands danger e-scooter of today could evolve into s Safety E-Scooter of tomorrow. I imagine it having a more-nearly-bicycle-sized front wheel for eating bumps and potholes without throwing the rider off, a shorter standing platform to give that front wheel room to function and steer and etc., a wider standing platform to make up for its being shorter, a tall narrow cargo cage perched over the rear wheel with its center-of-contained-cargo being ahead of the rear wheel’s center-of-support, maybe a built-in top-speed-limiter to keep it from going faster than a pre-determined safe-ish speed, etc.

People over 40 are not dare-devils and may not mind these changes. And there could be combined bike-and-safety-e-scooter lanes for these things to ride safe-ishly in.

Yves states, accurately: “So this latest development, demand destruction in gasoline, which is likely being paralleled by a contraction in demand for leisure and travel…”

My comment is about the use of the two terms “demand destruction” and “contraction in demand”. I’m uncomfortable with demand distruction because “destruction” is a term usually reserved for negative activity and is usually applied to an act which can’t be reversed without “reconstruction” while “contraction in demand” is a more neutral term matched by “expansion”.

My guess is that “demand destruction” has a history in economic writing but it seems like an odd usage to me.

My amateur layman’s guess is that demand-reduction forced upon the unwilling by brute-force economic events was called demand destruction. It often involved people becoming so dis-employed from their former jobs that they no longer had any money to buy any gasoline at all.

Perhaps demand reduction or demand moderation might be a kinder and gentler phrase for what we hope would be a kinder and gentler process of people who still have their jobs and revenue trickles being gently nudged, elbowed, perhaps gently slapped and kicked just a little, into using less gasoline than they would like while not having their basic survival activities compromised or limited.

For example, some people might decide to try figuring out just where their own car’s speed of hitting-the-airwall is . . . and learning to drive just under that speed so as not to reduce their own miles per gallon by not causing their own moving wall of air resistance against their own car going forward.

There has definitely been a slowdown in air travel which has to be contributing to this post. I live around 20 minutes from a major international tourist trap airport. The traffic has picked up somewhat but still is not like 2019. Plus, people like me are hesitant to get on “CV tubes” if we can avoid it.

This statement is only true with conventionally-powered grids in temperature weather. If you’re in the middle of a cold winter night and your grid includes large amounts of solar, the phrase “huge amount of idle capacity” does not apply.

Heck, we’ve even seen problems during heat waves, even though solar production more closely (but alas, not perfectly) aligns with electrical demand. The challenge, of course, comes during that period of misalignment immediately after sunset, when solar arrays go idle but the air is still hot. Plugging your car into the charger as soon as you get home is unhelpful here, which is why California recently asked EV users not to charge their vehicles: https://www.newsweek.com/californians-told-not-charge-electric-cars-gas-car-sales-ban-1738398.

High prices lead to demand destruction. This is desperately necessary. If the sanctions on Russia have a large role in raising energy prices, then they are a net positive for the world.

my wife and i decided to limit our travel to one day a week, wednesday, that is a day where we ship, buy, and eat out.

the high price of fuel has sent shipping prices through the roof. its affected our business, plus the price we pay also to go out.

wednesday like friday is a pay day for a lot of people. wednesday the highways and roads were always busy, stores full, same with eating establishments.

that is no longer the case. inside stores its so quite, you can hear a pin drop. no lines at the post office to ship, no long waits for food.

just think, the idiot hedge funds that control general motors dumped the volt for pickups, once again. so much for the vaunted efficient corporations.

michael hudson is correct, we are still in the obama depression, but it really should be called the clinton/obama recession. because all obama did was bail out bill clintons policies, then doubled down on them.

it was obvious we were heading into a depression before clinton had even left office. bush the dim wit did drop helicoptor money and said go shopping. but once that wore off, it was all down hill from there.

Higher prices on just about everything cause most of us to clamp down on our variable costs. Recently, gas prices have dropped but they still aren’t back to last winter”s prices here. So to pay for your electricity, water, insurance ( both my car and homeowners have gone up more than normal), etc., you try to cut buying stuff, eating out, optimize your gasoline use, and really work the food budget.

On a personal note, we were basically forced to retire early by a combination of vaccine mandates and the caregiving needs of my elderly parents so we aren’t commuting on a daily basis anymore. We have a shopping day where we do all our errands and have several days a weeks where we don’t leave the house at all.

We could even call it the “Clintobama” recession if “Clintobama” sounds catchier than Clinton/Obama.

100%

I even came up with a word for mushing the Clinton-Bush-Obama presidencies together into one putrid bowl of moldy oatmeal and sour milk . . . Clintobusha. The Clintobusha recession.

If “Clintobusha” is a step too far, I imagine it will be quietly forgotten.

I don’t drive a car. I now commute to the big city for medical treatment once a week. The buses are increasingly packed. I sometimes take the commuter train that runs only in the morning and evening. Recently the train I was on had a mechanical problem and we had to detrain and wait for the train behind us. I was astonished at the size of the crowd and we all fitted into the next train.

My point is that public transport is the only solution for minimum wage workers that don’t have the option of working at home. With costs increasing in every area, transport is a good choice to help reduce one’s cost of living as is selling one’s car. I decided not to replace my vandalized car. It’s a major chunk of a low income budget when factoring in the costs of insurance, maintenance and repair. If it’s a choice between a roof over one’s head, less food and/or light and heat, the car will lose, unless, if course, it already IS your home. Sigh. I am lucky to live in an area with lots of public transportation choices. People in rural areas don’t have as many options.

When I lived in the Philippines(two years) there was Public Transportation everywhere I went. Even in the rural area’s. Buses, tricycles, vans or the famous Jeepneys. Many people are able to make a descent living owning vehicles for public transportation. I have a brother-in-law there that owns several vans and makes a living doing it. Poverty is high so a lot of people don’t own cars, a cheap motorcycle is about it for a lot of family’s or nothing at all. Ever seen a family group of 5 people on a Honda 150? I did.

I was just thinking what if the high cost of vehicle ownership, insurance, gas, etc. will drive the same thing happening here in rural USA like were I live.

Then I wake up and think “Uber”

I forgot to make my point which is that perhaps some of the demand reduction is due to people ditching their cars completely. TINA.

Economists talk about “animal spirits” when it comes to investing. When it comes to every day life these days I’m of the view that the animal spirits have been greatly subdued for a variety of reasons. Everything seems to be less enjoyable these days. Traveling is often a nightmare. The cost of living is increasingly expensive. The saber rattling by the United States (and NATO) is unsettling people. COVID is still with us. The economy feels as if it may collapse at any moment. And so on. Rather than getting out there, traveling hither and yon, shopping until they drop, and consuming like all get out many Americans have decided to hunker down and wait out the storm(s). This may explain at least partly gasoline demand destruction as well as the decline in electricity demand.

Plants have to survive in place. As more of us have to try surviving in place, and enhancing our chances of being able to survive in place, we may start thinking in terms of “vegetable spirits”.

I have read that Palestinians and perhaps other East-Mediterranean Arabs view the prickly pear cactus, the “sabra” ( which is a Arabic word) as displaying the quality of patient and persistent survival-in-place. I believe their word for “survival in place” is “sumud” which I understood as something like “hang-tough-itude”

but is probably better defined and explained here . . .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumud

Perhaps such an attitude could be reworded for the American context and could lead its adherents to use as little gasoline as feasible without compromising their own minimal health-and-life-maintaining survival-in-place.

Perhaps enough demand destruction might lead to enough supply destruction that further price-rises are forced, leading to more demand destruction which would lead to more supply destruction , and round and round down to a more time-buying level of gasoline use.