This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 917 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year,, and our current goal, expanding our reach.

Yves here. This post by Tom Neuburger is ultimately about the coercive power of capitalism, or more specifically, a system which requires non-capital-owners to sell their labor as a condition of survival. It’s not as if pre-modern societies don’t wind up having most engage in labor to live…think of subsistence farmers. It’s tgat the power dynamics that are different. And that’s where politics and political positions like conservatism and liberalism come into play: they can have some impact on the rules and informal practices under which capitalism operates.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

In the capitalistic hierarchy of values, capital stands higher than labor, amassed things higher than the manifestations of life. Capital employs labor, and not labor capital. The person who owns capital commands the person who “only” owns his life, human skill, vitality and creative productivity. “Things” are higher than man.

—Erich Fromm, The Sane SocietyThere must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, and out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.

—Frank Wilhoit, defining conservatism as a political philosophy

By a roundabout route — starting with a very good piece from The Lever on the next abortion battle, to Cory Doctorow’s reflections on the latest poisonous modern aristocrat (Barre Seid), to a reflection on modern liberalismat Crooked Timber — I landed in my reading on a brilliant comment by composer Frank Wilhoit. This piece is about his comment.

Let me set the stage. The latest conventional wisdom is that America is a divided nation, and those divisions are best expressed as those on the Right (Republicans and their supporters) opposing those to the left of the Right (Democrats and their supporters). The former are usually called “conservatives” — when they’re not being called “fascists” — and the latter are usually labeled “liberals,” or sometimes “progressives” if “liberal” is deemed too tame.

The True Definition of “Conservatism”

An earlier essay on conservatism by UCLA professor Philip Agre, an essay much read in Bush II years, held that “Conservatism is the domination of society by an aristocracy,” and thus conservatives seek to make the status quo “seem permanent and timeless” and “to pass on their positions of privilege to their children.”

This definition conflicts, of course, with the self-declared notions of conservatism as protector of “freedom.” But the notion of freedom in conservatism is confused and the identification is easy to refute, starting with the arguments in Agre’s essay itself, and ending with the actions of our “conservative” Supreme Court, whose definition of freedom seems to start with their freedom to tell you what do, and ends … right there.

Which leads to Wilhoit’s comment, written as a reader reply to a post at Crooked Timber. Wilhoit’s main point (lightly edited; emphasis mine):

Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit:

There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.

There is nothing more or else to it, and there never has been, in any place or time.

So far, we’re more or less in agreement with Agre. But Wilhoit has more. He opens this way:

There is no such thing as liberalism — or progressivism, etc. There is only conservatism. No other political philosophy actually exists; by the political analogue of Gresham’s Law, conservatism has driven every other idea out of circulation.

There might be, and should be, anti-conservatism; but it does not yet exist. What would it be? In order to answer that question, it is necessary and sufficient to characterize conservatism. Fortunately, this can be done very concisely.

Stop here, dear reader, and ask yourself the question Wilhoit asked. If there is a thing called “conservatism,” and if it is well defined by Agre and Wilhoit, what’s its opposite? Liberalism? Progressivism? Socialism? FDR socialism? Social democracy?

What is the genuine opposite of conservatism, if conservatism is the regime by which money is converted to power and control over others (as David Graeber put it many times in The Dawn of Everything)?

The dominance of man by man. Here the agents of the ruling order impose their will on those that presume to be resisting. In what country did this take place? Does it matter?

What is the true, mathematical opposite of the conservative position? What is anti-conservatism at its core?

Give up? Read on.

The Definition of “Anti-Conservatism”

The answer is in the definition of conservatism itself, and is indeed its mathematical (actually, logical) opposite.

If conservatism is a regime where, under law, some are bound and not protected, and others are protected and not bound, then anti-conservatism must be

the proposition that the law cannot [be allowed to] protect anyone unless it binds everyone, and cannot [be allowed to] bind anyone unless it protects everyone.

Simple, yes? Yet no, not simple at all.

Which of our proposed better-than-conservative societies — liberal democracy, socialism, social democracy, “FDR socialism” — does not enshrine the inherent right of those with wealth to exercise power over others?

All these alternatives are flavors of capitalism, all are sweetened subjugation, modified despotism. All soften the destructive effects of billionaire-controlled corporations and institutions — like “charities” (search for “Take Bill Gates”) and often government — so that many suffer less than they would otherwise have done, and few suffer more.

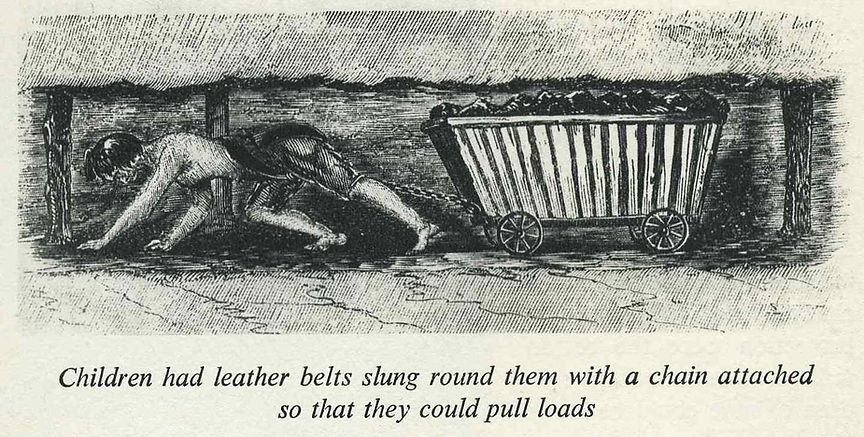

Child labor, Carolina cotton mill, 1908 (source)

MacDonald’s fast food worker, 2018 (source)

Does that make these institutions — social democracies; liberal democracies — better? Does it make them, like conservative regimes, bad, or evil? As Graeber and Wengrow replied in The Dawn of Everything, when answering the question “Are humans innately good or innately evil?”:

‘Good’ and ‘evil’ are purely human concepts. It would never occur to anyone to argue about whether a fish, or a tree, were good or evil, because ‘good’ and ‘evil’ are concepts humans made up in order to compare ourselves with one another.

None of these institutions is good nor bad. Do some cause less pain than others? Obviously yes. But to call socialism or any of its cousins “the answer” or “the antidote” to conservatism is to mistake these regimes for what they are not, and to mislead others to make the same mistake.

All of these regimes are flavors of capitalism. And this, from Erich Fromm, is capitalism at its core, modified or not, softened or not, sweetened or the bitter root:

The use of man by man is expressive of the system of values underlying the capitalistic system. Capital, the dead past, employs labor―the living vitality and power of the present. In the capitalistic hierarchy of values, capital stands higher than labor, amassed things higher than the manifestations of life. Capital employs labor, and not labor capital. The person who owns capital commands the person who “only” owns his life, human skill, vitality and creative productivity. “Things” are higher than man. The conflict between capital and labor is much more than the conflict between two classes, more than their fight for a greater share of the social product. It is the conflict between two principles of value: that between the world of things, and their amassment, and the world of life and its productivity. [bolded emphasis mine]

That those who control things command those who control life … is an abomination. The opposite should be true, yet hasn’t been since the earliest temple-states, the very first city-state days.

The Natural Order or an Unnatural ‘Sticking Place’?

Is it a natural condition, a natural state, the domination of man by man, of humans by their equals? Our species has been on this planet for 200,000 years, give or take. The earliest oppressor states, less than 5,000. Ninety-eight percent of human history is lost, so it’s a separate project to answer that question well.

But if this is not our species’ natural state — and I’m inclined, positive soul that I am, to believe that humans have simply become simply “stuck” (Graeber’s term) in just one of a large variety of alternative structures — then we could become “unstuck,” could “unstick” ourselves, could rise as easily as we made ourselves fall.

If “stuck in the current ugly social order” is not our natural state, we could free ourselves indeed of rule that hands power to money. We could relaunch our destiny, reboot our social OS to a saner state, and live in a way that’s truly anti-conservative.

Older others have lived far better than us — Stone Age others if Graeber is correct. If they, “mere cavemen,” could retain their freedom through most of our hidden past, why not their putative smarter cousins, we? I ask in all sincerity.

I work with modernized indigenous people from various parts of the world and have come to find the inability to define an alternative quite silly, since it’s right there. Many indigenous are great at showing those who will listen, so we don’t have that excuse either.

What I see is complex but I’ll do my best to share what I’ve learned.

1) the power axis is structure vs source.

Non-indigenous are obsessed with who has power and what rules they can make. I haven’t seen this in indigenous very much.

Different groups have different power structures but they all focus on the same goal: giving power to those who demonstrate commitment to providing for the whole. The focus is on outcomes and principles.

2) the relationship axis is transactional vs reciprocal.

As one friend put it, “rather than using our strength to increase our own position, we use it to increase our partners’ position. That way they gain strength and can use it to increase our position in the ways we need ”

3) the worldview axis is anthrocentric vs ecological

If we believe that human life is more valuable than other life, isn’t it natural that will play out in our social systems? Everything changes when relating to the world as a whole, including honoring the “inanimate” as family.

4) the space axis is universal vs local.

In both physical and spiritual/ideological space, the indigenous see that reality is rooted in concrete experience which will differ between places. Truth is neither Platonic nor relativistic, but built over time layer upon layer specific to location

—-

With these four axes in place, vastly different social systems arise…ones much more compatible with flourishing life. And from my perspective, much more compatible with scientific truths.

That said, there are definite trade-offs, such as conflicted relationship to individuality, difficultly organizing at scale and strong in vs out group bias. But as newer generations reclaim their indigenous heritage they are seeking to integrate modernity in a way that lessens those pitfalls. And they love to dialogue about it.

I would counsel anyone interested in this stuff that the dialectics in the Western world are totally played out and at a dead end. The dialectics between West and East still are fertile but the dialectics between indigenous and non is by far the most fruitful

I’m curious how this leads to in vs out group bias. Not arguing with any of what you said, as it’s in agreement with my understanding of different indigenous perspectives I’m aware of, and also in vs out group bias is definitely something that’s been the case for many indigenous peoples at different times.

These days it seems like a lot of indigenous people do feel a collective sort of global group identification as indigenous maybe, I’m not sure if this is an expanded in vs out group bias though?

Also I’m thinking that in vs out group bias is super present along different lines of separation in western societies, maybe all societies. But it seems like a lot of the values you discussed would possibly lend themselves to obviating this bias, so I’m just curious your (or others’) thoughts about it all.

Great question. I’m hesitant to answer much specifically because it’s so complex and also particular to different groups but my broad observation is it comes from a focus on group success, reciprocity and shared principles. Since the emphasis is on having the same intentions as well as demonstrated history then it is easy to be inward looking.

That might sound vague but it’s really hard to get specific without writing a ton. So I’ll just comment on your other points, particularly in contrast to western societies.

You’re totally right that western societies have group bias of course. The liberal idea that we are all one giant group is in the minority today and total historical anomaly. The explicit purpose of nationalism is to try to destroy this historical separation based on relating and rise it to the nation level based on bureaucracy. Capitalism also relies on it. This is the source of so much resentment today.

That said, I see western society as obsessed with rationalizing this bias through moralizing. It’s not enough to just be different, the other has to be evil or less than in some way. By contrast I’ve never heard any indigenous person dehumanizing or judging others. Even when I’ve been told about headhunting ancestors wiping out other villages (or modern equivalents) it wasn’t because the enemies were less worthy. It was simply because it resolved some conflict. I’ve also never heard them dehumanize those who oppress them. Perhaps some do, but I haven’t witnessed it.

Also, you’re totally right that there is global affinity for other indigenous but it’s not just because those people have the same identity but also that they relate in the same way. I’ve found that anyone who relates in that style will be accepted by many indigenous people as equals, although it takes a very long time to demonstrate it. The specifics of that style is beyond what I can summarize.

And then there is an interesting inbetween category, where many indigenous I’ve met feel ease when interacting with Arabs because they are tribal and East Asians because of their worldview/social protocols.

All this said, I totally agree with your point that the values lend themselves to obviating the bias and I don’t fully understand why they don’t. I’ve point blank asked friends about this and they don’t know either. They just say they focus on (a very broad definition of) family and their land and welcome anyone who wants to help with that. However, the young people who grow up in a modern context and so don’t have strong family/land connections do see it more on an identity and perspective level so I think that’ll change.

White liberals’ strong out-group idealization is sociologically unusual. In-group preference isn’t a bad thing in itself; the very constitution of a group depends on some preference for the existence of relations within and to the group over the absence of those relations. The variation in sufferability of any given society is determined by how that society discounts out-groups: are they part of nature (and therefore inferior objects, subordinate to us, and of only potential value, like material stock) or are they cousins “of mind” like us, just not “of us”?

Conservative societies, those who are self-consciously concerned with the fidelity of their social reproduction, tend toward the former. They tend to see all things narrowly in terms of the system of values their societies are reproducing. Those values inevitably celebrate some kind of general subjection of nature to human will, covering the gamut from such mundane materialities as chemistry or agriculture, to idealism as particle physics or the circulation of souls among predators and prey. Thus, two definitions of state, the total description of a system and the continuous process of creating order, converge in a wild tangle of ontological hackery. It is when such conservative societies, adapted to the certainty of their own self-replication under austere conditions, stumble into material abundance, and leverage that abundance to deliberately construct persons out of the aforementioned material stock, that the invasive weeds of empire propagate.

IMO, the healthiest organizational principle of the four is the last: universal vs. local. I offer the half-baked concept that electromagnetism seems to offer a fertile source of metaphor on which to build the mythos of a collectively oriented, appropriately technological society, with an eye to soft de-industrialism and de-commercialism. The inverse square law generates fuzzier theories of property based on proximity, guarding against the sort of absentee rule enabled by neo-Platonism and capitalism. It inspires an ethic of “intentional community”: if you’re going to commune, have intent, avoiding all this face-time rubbish. Rather than seeking immunity to mystification, such Maxwellian mysteries (incomplete, as they do) would circle back to materiality. It seems fairly resistant to eschatology, and lacks very much space for charisma (but I’m sure some hack could make something up). Rather than universalism, Maxwellian moral theologies might offer cautionary critiques of “moral entanglement” and other “non-local” social phenomena. If I were more of a fiction writer, I would explore this line of thinking more deeply. I half hope someone already has.

It seems to me that in group bias for indigenous system is less pronounced because at local levels, they all consider themselves in the same group. Albeit, from what I have heard, in western Canada first nations communities, sometimes hereditary leadership becomes an in-group by itself…

I have come to view liberalism as a theology. Specifically one that provides (incoherent) theoretical justification for capitalism. Unlimited wealth accumulation, transferability, and free conversation into power and back again are sacred in this theology.

John Gray writes frequently of notions of progress and human perfectibility as tenets of something very like religion. I enjoy him enormously, and learning to discount those ideas certainly removed a lot of cognitive dissonance from my life.

I was unfamiliar. Thanks for the tip. Maybe I’ll put Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals into my reading list. An antidote to Vonnegut?

Mikkel,

I am confused by what you mean by “Truth is neither Platonic nor relativistic”. To see the world “built over time layer upon layer specific to location” is a relativistic perspective.

Conservatives are more absolutist with a static world view. Non-conservatives have more consideration for context, time, and the limits of abstraction.

I think there is an important difference between meaning and truth. Truth is sought by method, and is presumably replicable regardless of who replicates it. Meaning is established by custom, and meaning only remains stable so long as customs persist in the same pattern going forward. Conservatives tend to value meaning over truth, and tend to want to protect the sphere of meaning from liberal encroachments, which I suppose you could call static. It can come to look like what we call fundamentalism, although why should truth have priority over meaning?

As far as consideration of context, time and the limits of abstraction, I’m not sure on what basis you make that statement. A lot of the post-war conservatives came out of Trotskyite groups, had studied Hegel, Marx and had familiarity with German historicism, and weren’t nearly as stupid as you make them out to be. You can take a figure like James Burnham, who has lots of consideration for context, time and the limits of abstraction. Or Mary Harrington now.

Truth is simply reference to the world outside the mind. Not having your mental models aligned with reality is insanity and what leads to the worst outcomes. So yes, I think being slavishly devoted to meaning without constantly tracking real world outcomes is pretty stupid.

I’m not familiar with Mary Harrington, but I just read a piece titled “Am I really a threat to democracy?”. Hopefully that’s the Mary you’re talking about. I think of conservatism as a short-circuit problem of the mind. Related ideas are conflated and made to be equivalent when in fact a full examination will show them to be quite distinct. That article is an example of this sort of thinking.

I rather liked that article. Also, all about context, time and the limits of abstraction. . . and any person who is public enemy number one from the standpoint of the National Review is probably doing something right.

I also disagree that truth is necessarily more important than collective meaning, because people are willing to fight for meaning, whereas even Galileo was willing to recant over a simple matter of truth.

Is there a benefit of talking about “conservatism” or “liberalism” or any other political ideology outside of a particular historical and institutional context? Second, is there a distinction between say, conservatism, understood as a disposition, and for example, Conservatism as understood by the Republican Party in 1984?

If conservatism is “the domination of society by an aristocracy”, this sounds like a European framework, of a class of aristocratic landowners fighting to maintain domination in the face of state centralization, fiat currency, standing armies and early industrialization. There certainly were, historically, European political movements in prior eras that meet that description. However, those social forces have been washed away in history in Europe (to the extent that the Aristocracy survives in Europe, it has intermarried with capitalist classes and rests on a very different power base than in the 14th century). Further, the only thing approximating the European experience in North America would be the slave plantations, and they were regional and were wiped out in 1865.

If conservatism if restricted to aristocracy, then conservatism as a political force was washed away by the close of the end of the 19th century, or 1918 at the latest, and there is no American conservatism, outside of nostalgic Southern reactionaries.

If we broaden the framework with the observation that complex societies are hierarchical, drawing on Robert Michels insight and others, and we define “conservatism” as a philosophy intended to legitimate and perpetuate the status quo elites at the top of the hierarchy, you can do that, but it immediately raises the problem of the way this understanding conflicts with existing political lexicon. If we ask the question whether Marjorie Taylor Greene or Hillary Clinton ideologically reflects the interests of status quo elites in America, it is pretty clear that MTG is basically a freak from the standpoint of elites, and elites are very comfortable with Clinton, even if they disagree with some of her priorities. From this standpoint, MTG appears to be the anti-conservative, and Clinton the conservative. Indeed, the Democratic Party’s invocation of “extremism” seems to overlap with what we would call “anti-conservatism” here.

Another way of looking at conservatism is on identitarian grounds and attitudes regarding human flourishing. Conservatives tend to see embracing and recognizing historically-rooted identities as integral to human flourishing, whereas liberals see repudiation of historically-rooted identities as liberating for both individuals and society. In substitution for a historically received identity, liberals seek to construct their own identity, in keeping with a social ethos of consumerism. In terms of Dasein, a person is thrown into the world, and into a concrete and historically bounded context due to factors beyond their control. The conservative flourishing involves accepting the limits imposed beyond the self, and understanding the self as bounded by ancestors and by descendants. In contrast, the liberal project, the trans project, is to transcend the bounds of the self, denying the historically given, and seeking immortality over posterity, whether immorality is achieved through scientific conquest or through (more often) fame. In terms of consumer capitalism, liberalism is connect to consumerist ideologies, utopian conceptions of the world as an undifferentiated ego or a workforce of interchangeable parts. Unsurprisingly, liberal advances politically tend to lead to the creation of markets and wage labor in areas that previously remained outside of the ambit of markets and wages. In this respect, conservatism is anti-capitalist, or at least, anti-consumer capitalist, but perhaps open to a critique that it is reactionary–certainly feudalism was anti-capitalist as well. This flavor of conservatism tends to run petti-bourgeois, and may be understood in terms of the class orientation of the petti-bourgeois to some extent (and also connected to the French anarchist tradition, Proudhon and Sorel).

On a related note, it makes sense to consider attitudes toward the French Revolution. One way of regarding customs and traditions is as the result of a process of social evolution, that customs have survived because they have worked for peoples in the past, without necessarily being self-evidently rational (lots of people have historically had taboos about cannibalism without understanding prion disease). From this perspective, custom and tradition are presumptively correct. A contrary framework is that traditions and customs are based in superstition, oppressive and serve no useful function, and that society should be ordered rationally, in a way resembling a geometric proof. The locus of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment is very much that of geometry, you can almost see it growing from Descartes’ unity of geometry and algebra. Geometrical proofs are derived from entirely abstract and non-empirical set of first principles, and are universal. They are completely divested from historical givens. The basic conflict is between an evolutionarily-based and historically-based conservatism and a context-free universal liberal rationalism, and this sets up a lot of the contested ideological space of the current day.

Another view of conservatism is associated with libertarianism and laissez-faire economics, seeking to keep the state out of interfering with business. This is not about a battle between elites and a counter-elite usurping power, nor is it about egalitarian battles, it is primarily about a battle between elites in government and elites in the private sector. Nor is it particularly consistent, as the state is desirable when it is necessary to bail out financial institutions or enforce drug patents, but undesirable when regulating carbon emissions or offshore drilling. One can even ask the question of whether such a position is actually authentically conservative, or simply an outdated version of liberalism, as the exponents of this strain of ideas often call themselves “classical liberals,” not conservatives.

In sum, there is not much benefit to political generalizations outside of a real political context, they are generally empty, as are their Manichean opposites. Further, if someone describes themselves as a conservative, it can have all manner of a meaning, in the same way liberalism is fundamentally ambiguous. That being said, it is hard to view capitalism as anything other than a product of Enlightenment liberalism, even if a successor ideology like communism is also a product of the Enlightenment.

Great comment! This was my immediate reaction too but didn’t think it could be captured as succintly as you have put here.

Ditto for me. “Conservatism” must always be socially and historically contextualized. I also loved the Marjorie Taylor Greene vs. Hillary Clinton example. It so nicely illustrates how such terms as “conservative,” “liberal,” or “progressive” are used as ideological fog machines to mask actual relations of power.

I do think Neuburger is on the right track, however, in emphasizing that with capitalism, the relationship between people and things as relates to systems of power undergoes a fundamental change. It is a uniquely de-humanizing system. Whatever his deficiencies, Marx got that right.

It was my impression that conservatism was a (pre)disposition to try to keep things the same, to resist change, which for many people is a rational strategy given their circumstances, information, and capabilities. I refer not just to elites but to ordinary people. For example, a reasonably informed working-class person in the US might wish to be conservative about the New Deal and similar projects, not seeing anything better coming down the road. Liberalism, on the other hand, is a specific political philosophy or ideology associated with Locke, Jefferson, and other usual suspects, usually adapted in various ways to modern conditions. You could, therefore, be conservative about liberalism, although this seems to be an almost reactionary harkening back to ancient, fabulous ways of rugged individualism and free enterprise which for the most part seem to have never existed. Mostly, though, I think the words have become useless because they are used in such confused ways, to which my observations have no doubt contributed. But it is especially interesting to observe that many who describe themselves as “conservatives” favor not keeping things the same but plunging into the most radical, dubious schemes imaginable inspired by worship of capitalism and imperialism.

So much of value in your comment, KD. The penultimate paragraph reminded me of Mark Blyth’s pithy description of the neuralgic anxiety which has afflicted Liberalism (due to its core contradiction) from the very beginning — the problem with the state: “can’t live with it, can’t live without it, don’t want to pay for it.”

I like the framing of this one. People often chafe when you say the Republicans and Democrats are more or less the same. Maybe labeling both parties as factions of conservatism will make some on the ostensible “left” think a little bit more about what it is they are voting for when they pull the lever for the likes of Joe Biden. Maybe. I won’t hold my breath though.

The “lever pulling” problem in a First Past the Post ‘two’ party system is that rational Progressives know they cannot get from Here to Their Own Peculiar Golden Sunlit Uplands without moving incrementally in the correct direction and ‘conservative’ Democrats, or DINOs, know that about the Progressives, and traduce them into voting for the promise of change without it ever developing into something threatening to the status quo.

It’s a problem that anyone who wants real change (at least in the Anglo-American capitalist sphere, that has amassed much of the power) has yet to solve.

I’m writing this while sitting in Slovenia, within the EU, which seems to have many of the good things we would like in the US and UK. The European method seems to be better for a broad mass of people, for the time being.

I guess a handy historical comparison is Whigs and Tories in the UK: divided over divine right and the state of nature, Deism and Providence, free trade and protectionism – but united on the protection of property at the expense of those whose only asset is their labour. Meanwhile, the machine of accumulation grinds away – until constrained by state action in the face of worker unrest and war.

In the West these days all parliamentary parties are mere factions. Factions of extreme capitalism or conservatism in the article’s terms. In the US we have a corporate, russophobic faction versus a Christian, sinophobic faction.

I’m currently reading “The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order” by Gary Gerstle (because I saw it mentioned on NC) and it is fascinating to see the overlap between Republicans and Democrats as both “sides” wholeheartedly embraced the ideology. The lines between liberal and conservative get awful blurry.

I’m not finished with it yet so I haven’t gotten to the”fall” part, but from looking around it sure looks a bit premature to be talking about.

Gerstle’s book is great — I’m pretty sure he avers that the “fall” is a process, and that we are still in its relatively early stages.

in the usa, at least, this dichotomy has had very little use-value for some time.

folks i interact with out here are always confused by the “contradictions” i appear to represent…liberal, socialist, anarchist, small-c conservative, , all rolled up into me.

“do i contradict myself? verily, i contradict myself: i am large…i contain multitudes”-Whitman.

from my own internal perspective(Rumi-“who looks out from these eyes?”), i am sufficiently consistent.

and that’s what matters to me.

last year or so…due to comments found here, at NC…i’ve been leaning more towards Humanist vs Anti-Humanist…as long as a dichotomy…a black/white manichean binary is necessary for ordinary rural texans…i think that sums my view up better than the tired old L vs R, D vs R, etc.

after all, the politically aware out here(sic) think that hillary and the mainstream neolib dems are “far left”.

i think we’ve been well into a Nimrodian agnosis crisis since at least reagan(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raph%C3%A8l_mai_am%C3%A8cche_zab%C3%AC_almi )…and i don’t think it’s an accident of history…nor some natural evolutionary feature of late capitalist civilisation.

i think that, rather, the various cliques within the PTB have taken certain human habits of mind and assorted common biases, and ramped them up(see:the classic conspiracy theory derived from “quet weapons for silent wars”-society as a circuit board, with diodes and capacitors that can be manipulated).

the cia’s (as a stand in for a broader mindset) fundamental purpose is the sowing of confusion.

people like MTG and Boebert are merely created out of habit by a certain faction within the Imperial Project Manager Class.

…and, related, i’ve lately been encouraging cousin to read the first six Dune books…so that he can eventually get to God Emperor…because it contains many odd flowers that help in thinking about these things.

Pauline Kael, who grew up on a chicken farm near SF, once wrote a review titled “Here comes that clean, healthy peasant again.” Here’s suggesting those who glamorize indigenous and back to the land haven’t really tried it or the grinding and often gross hard work that goes with it. If those indigenous societies seem less obsessed by power and more communitarian it likely has to do with them being much more on the edge of survival. In other words it’s their environment that is different, not the people themselves. Change that environment and they turn into us.

I was about to elaborate on a related concept that addresses the point of “what is conservatism.”: It takes a fairly complex society, with a fair amount of surplus to go around, among other things, to develop an “aristocracy,” ie a professional governing class in whom power will be concentrated. Less complex societies, without enough surplus to support an aristocracy or complexity to justify it’s existence, would necessarily be “anti-conservative” by definition. But this also means that virtually every complex society would necessarily be “conservative” in some form, though.

I think there is a big difference between a traditional aristocracy, which obtains land, slaves and/or peasants by force, and maintains it power by threat of force, and elites in a political economy based on financial capitalism, where power is held by those who possess large amounts of capital, and workers are paid wages, consistent with Marxist dialectical materialism. Very different social relations, even if they may both be examples of systems of domination and exploitation. True aristocracies are paternalistic, and wage labor tends toward purely transactional social relations.

the latter of your examples has more abstraction baked in…both where power lies, as well as how that power operates upon the individual.

but for hyperabstraction, the promised hobbseian revolution* would have happened circa 1976.

*-see: gop state platforms, over time.

And change the environment again, as in the end stages of overshoot that we are approaching and we become them.

I would posit that Pauline’s chicken farm was more about an industrialized monocropping agriculture than any peasant or indigenous mixed farming that includes a few chickens running around.

Her chicken farm is more like the ones today with their indentured serf owners/operators.

That’s capitalism and the conservatism he’s describing.

Pauline’s experience was in the 1920s and her father owned the farm. She is long gone from us. I’m sure it was more like the family farm my mother grew up on.

Kael went on to Berkeley and then dropped out a half a year from her degree in philosophy. But her outsider status (then true of almost all West Coasties) is a big part of her celebrated writings.

I’ve never liked Neuberger’s spouting of conventional wisdom. “Conservative” and “Liberal” are framings which have lost all meaning as KD’s excellent comment explains.

In my personal world-view Bernie Sanders is the only true “conservative” in American political life, since he wants to “conserve” the dignity of all persons and to “conserve” the natural environment to which we owe our very existence. He is the embodiment of the Talmudic account of Rabbi Hillel summarizing the Torah in the time he could stand on one foot: “Do not do unto others that which is repugnant to you. Everything else is commentary.”

All human societies suffer from the problem of Elite Impunity that has taken hold in ours. There is no “noble savage.” Ever heard of the Gran Tzompantli de Tenochtitlàn?

I have raised children (with mixed success — but a .500 hitter would merit the Hall of Fame). Children are born helpless and must learn empathy or they will fundamentally experience the world as a struggle for power and control. It is the unsocialized child’s struggle for power and control that is at the core of what I see as “liberalism” expressed in the Elite Impunity of both the Clintons and Trump.

Is the notion of Elite Impunity, the notion that “There must be in-groups whom the law protectes but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect” conservatism? I personally think not. The lived experience of Elite Impunity and the mis-labeling of “conservatism” and “liberalism”are the core of our society’s current “divide.” The BLM Movement and the January 6th Movement are two sides of the same coin.

american liberalism was different than european liberalism. american liberalism was born out of the enlightenment.

european liberalism has much in common with fascism.

bill clinton killed american liberalism. american liberlism is now european liberalism.

https://www.rawstory.com/2016/03/how-bill-clinton-and-the-democratic-party-killed-an-essential-part-of-liberalism/

“To Frank, though, Clinton was responsible for the death of an essential part of liberalism. “Erasing the memories and the accomplishments of Depression-era Democrats was what Bill Clinton and his clique of liberals were put on earth to achieve.” One of the president’s favorite sayings was that “the world we face today is the world where what you earn depends on what you can learn.” This reflects, in Frank’s interpretation, the core New Democratic principle that “you get what you deserve, and what you deserve is defined by how you did in school.” Given such a premise, which is “less a strategy for mitigating inequality than it is a way of rationalizing it,” it is hardly surprising that Democrats have little interest in championing the cause of workers.

Frank is critical of Clinton-era developments such as the president’s emphasis on balancing the budget in the face of a recession, the appointment of Goldman Sachs alum Robert Rubin and Ayn Rand acolyte Alan Greenspan to prominent positions, the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994), the draconian crime bill that both Bill and Hillary Clinton now disavow (1994), welfare reform (1996) and the termination of Glass-Steagall (1999).

He is also displeased by President Obama’s decision to continue and expand the Bush bailouts in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Despite the hopes of many of his liberal supporters, Obama has turned out to be a moderate on inequality. Taking office in a turbulent atmosphere in which a large constituency wanted banks (and bankers) to be punished for their role in ruining the economy, Obama did little on this front.

Frank’s interpretation of contemporary Democrats as those committed to the interests of the professional class explains why. “We must acknowledge the possibility that Obama and his team didn’t act forcefully to press an equality-minded economic agenda in those days and in the years that followed because they didn’t want to.”

Over the last several decades, many liberals and leftists have expressed dissatisfaction with the Democratic take on economic issues. What makes Frank’s book new, different and important is its offer of a compelling theory as to how and why the party of Jefferson, Jackson and Roosevelt is now so unlikely to champion the economic needs of everyday people.

The Democratic abandonment of economic issues, Frank helps us understand, is due neither to cowardice nor to corruption. It is instead an expression of a coherent and consistent philosophy, albeit one that might not be terribly progressive.”

“There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, and out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

What does the law protects? First and foremost their private ownership of physical (slaves included) and more an more immaterial assets and ideas, and then through the influence of wealth and being anchored in the various networks of power, they are protected from their own unlawful actions in the courts and by those that hold the “lawful” baton and gun.

Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have some interesting takes in their book “Capital as Power A Study of Order and Creorder”.

Myself, I am reverting always to the Aristotelian description of political systems: democracy, with many a times random selection of representatives from the citizens, oligarchy and tyranny. With oligarchy the most stable and persistent. Because the in-group, the present network of networks of corruption as described by Zephyr Teachout in her work “Corruption in America From Benjamin Franklins Snuff Box to Citizens United” has developed tools and techniques to protect and magnify the wealth.

And with the Tyrant as the potential arbiter. The Tyrant (monarch) being the most hated by the Oligarchs throughout history – unless it serves them and unless they select her/him to protect them. This sentiment has been mostly reciprocated by independent tyrants, which tended to be populists…

Another problem we have is that intellectual resources in humans are following a normal distribution curve.

The Honourable Leader of the Conservatives and His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, ———-

Sir

Congratulations on your election to the leadership of the Conservative Party of Canada.

I really appreciate your new calmer tone when asking questions in Parliament.

I thought you might be interested in a definition of Conservatism which can help you in carrying out your work in our Parliament. Here’s a quotation from the article linked: https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2022/09/liberalism-is-not-the-opposite-of-conservatism.html

Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit:

So far, we’re more or less in agreement with Agre. But Wilhoit has more. He opens this way:

There might be, and should be, anti-conservatism; but it does not yet exist. What would it be? In order to answer that question, it is necessary and sufficient to characterize conservatism. Fortunately, this can be done very concisely. ( End of Quote.)

So you can see that you have a big job ahead of you confronting the conservatism that we are already enjoying in our current Prime Minister. It will be a battle with which the Conservative Party will win the next election in 2025. You see the problem, do you not?

We Canadians know the game is rigged by those in-groups who are protected by law and the rest of us are “the out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

Just take a good look at the financialization of our economy since 2008 after the Great Financial Crisis when the banks were bailed out and the elite created yet more billionaires and were given access to QE while the rest of our society did not gain any appreciable increase to aid in their existence. Look carefully at what has helped create inflation and I suggest you look at all the corporations and organizations that actually made huge profits during the Pandemic. (Hint: oil companies)

You will have a huge job convincing people that you understand the economy if you don’t stop saying you are going to “fire” the Governor of the Bank of Canada. You are in the right area but have the wrong persons in your sights.

I shall follow your progress with much concern.

Sincerely,

JEHR

“How can we get back what we have lost without confronting those who took it?”

https://ilsr.org/post-2359/

We Forget What It Was Really Like Under the Clintons

by David Morris | Date: 31 Dec 2008 | Facebooktwitterredditmail

Socialism is the project of restoring labor’s power over capital, so it’s a bit slanderous the way it’s treated here. You can claim it doesn’t work (even though actually existing socialism did achieve great material benefits for workers despite stalinism/etc.) but not that it isn’t opposed ideologically. Claiming anti-conservatism doesn’t exist is moronic. He’s right that both so-called conservatives and liberals are both in agreement on liberalism/neo-liberalism as the fundamental framework, but wrong that anarchists, socialists, and communists don’t represent real opposition. His conclusion seems to be anarcho-primitivist, essentially saying the problem is civilization itself, but he doesn’t appear to know about that position’s existence either which is kinda pathetic.

Debt is the shadow of profit.

The capitalist system controls technical advance in order accrue the debt of others to it and its guardians, as to their primacy. When capitalist production is convincingly producing “progress” the burden of this debt is acceptable. As that illusion increasingly fails, capitalists will amplify fraud and force to maintain their “credit”.

People really do seem to take umbrage with the term “aristocracy”.

Makes one think of Upton Sinclair and his lament that Americans will take socialism in action but not in name.

The opposite of conservatism is civic republicanism. One of great tragedies of USA history is the diminution of civic republicanism and its displacement by liberalism. Some historians have argued that without liberalism displacing republicanism, capitalism would not have developed the way it did.

“..if conservatism is the regime by which money is converted to power and control over others”

Civic republicanism (“a republic, if you can keep it”) has always stood in suspicion and hostility to concentrated wealth. Machiavelli (who is smeared and misrepresented as a soulless advocate of real politick) explained in Discourses on Livy how the Romans created the system of tribunes to oppose the power of the rich, who had corrupted and seized control of the Senate. And Machiavelli recounts how, a few hundred years later, the rich finally killed off the republic and raised the empire on its grave.

Only civic republicanism does not “enshrine the inherent right of those with wealth to exercise power over others.” Why is civic republicanism not much mentioned or discussed anymore? is it because USA has degenerated into an oligarchy, and an oligarchy cannot tolerate the precepts and principles of republicanism? Why is this the most famous saying of Benjamin Franklin

and not this?

In The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787, Gordon Wood wrote:

A bit later, Wood wrote:

Note the formulation in the last sentence: a constitution within its subjects, the citizens. This is not the conservative and libertarian “originalist” wet dream of a national government bound, tied and gagged by a strict adherence to the enumerated powers of a written constitution. This is an unhesitating embrace of the noble qualities of humanity to share and cooperate. It requires community to pursue collective goals. Cutting a canal. Building a railroad. Landing people on the moon. Building a highway. Providing electricity to an city or town. The model was established by Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia in the 1740s with his Junto of young men dedicated to improving themselves so that they could improve the human condition in general. Just read the founding documenst of the American Philosophical Association, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Agricultural Society, or any of the dozens of manufacturing societies that were established in the same cast. [See Peskin, Lawrence A., Manufacturing Revolution: The Intellectual Origins of Early American Industry, Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.]

In Philadelphia’s Philosopher Mechanics: A History of the Franklin Institute 1824-1856 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), Bruce Sinclair writes

“the majority of Americans in those years placed their faith in democratic ideals and the applications science. They saw in that combination the potential for political freedom, the end of class privilege, and a basis for equal economic opportunity…. science also had ideological implications for Americans of the early nineteenth century. Science was almost always thought about in terms of education, and there it became intertwined with democratic ideals. Science was “useful knowledge,” a term widely popular in the 1820’s and used consciously in opposition to that idle learning which characterized the aristocracies of the Old World, where education was restricted by class lines. If it were made widely available, useful knowledge—training in science and its applications—would give any individual the chance to advance as far as his talents would take him. That was not only democracy’s goal but its best warranty for survival. Since useful knowledge was also the key to the country’s natural abundance, it would become America’s mission to the world to demonstrate that democracy was the political system best designed to produce wealth and freedom for its citizens. Technology, as Hugo Meier has persuasively argued, “proved to be a catalyst, blending the ideas of republicanism with the rising democratic spirit in the early national period.”

A key often overlooked is that the United States government was founded with a Constitutional mandate to promote the General Welfare. This proved, at times, to be an ideal more than the reality, but the point remains: from the very beginning of the United States under the Constitution, all economic activity was supposed to directed in the public interest. That this is no longer the case is a searing indictment of our own neglect and our own mismanagement of our government. (And it is pertinent to note that conservative legal scholars have long dismissed the Constitution’s Preamble as having no legal power; conservatives regularly trot out this argument whenever someone argues that “to promote the General Welfare” gives sanction to a “welfare state.”)

Today, the idea of progress is mostly about increasing and extending individual consumer choice. In the founding era, by contrast, the idea of progress centered on increasing the power of humanity over nature, to free humanity from hard physical labor and allow more people more time to engage in intellectual and cultural advancements. As John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail:

Unlike today, the idea of progress In the founding era was focused not in the individual gaining access to a better or cheaper item of consumption, but on general improvements in agricultural and industrial processes and technologies that increased the productive power of society as a whole. The goal was not the bowdlerized neoliberal understanding of today, to merely make commodities cheaper and more profitable. It was lessening and even relinating the need for physical labor, by introducing machinery to produce what hundreds of men and women previously produced. This technological progress elevated humanity from mere brutes exerting muscle power similar to horses, oxen, or mules. This strengthened and deepened the radical claim of civic republicanism that the lowest-born person, working in mud dawn to dusk, was the full equal of any nobleman, or even duke, duchess, queen or king.

Moreover, the cornucopia of increased production began to significantly lessen the differences in the material conditions of life between citizens, and monarchs, oligarchs, ad ruling elites. Where once books were possessed solely by ruling elites and ecclesiastical orders, every family came to own a “family bible,” then an assortment of books. Benjamin Franklin’s founding of a public library – not a college library or a monastery library, but a public library – was a revolutionary incursion on a traditional preserve of elites. Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia was founded in November 1731 – why had no such institution been created in Britain or elsewhere in Europe in the three centuries since Gutenberg’s invention of the moveable type printing press in the 1440s? The answer is that the ideology of civic republicanism had not yet found a land in which to reign. Nor had there been a government dedicated at its founding to promoting the General Welfare.

In Civilizing the Machine, Technology and Republican Values in America, 1776-1900 [New York, Grossman, 1976; Penguin 1977] John E. Kasson argues that

The concept of civic virtue is reviled by liberalism, with its insistent focus on the rights of the individual. Here is where what makes a republic different can be clearly seen: while the inalienable natural rights of a human being are central to both liberalism and republicanism (with its insistence on rule by law, not just men), only republicanism counterbalances this focus on individual liberty with the right and needs of the community. The classic statement of this is Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1876), the Supreme Court decision upholding the power of state governments to regulate private industries that affect “the common good.” (Munn came under sustained attack by corporate lawyers — dominated in those days by the railroads — which had been created using vast grants of public lands — eventually leading to the legal fiction of corporate personhood and the dreadful Lochner era of jurisprudence.)

So let’s be very clear here: capitalism and the importance it places on self-interest, which not only enables but glorifies selfishness (Ayn Rand merely took things to their logical conclusion) is a fundamental rejection of republicanism. Let me repeat that: capitalism is a fundamental rejection of republicanism.

“In the capitalistic hierarchy of values, capital stands higher than labor”

In response to Erich Fromm’s dishearteningly accurate observation that

we have Abraham Lincoln’s First Annual Message, December 03, 1861, in which Lincoln deplored

And Lincoln was not stating anything new or novel — he was merely repeating the founding principles of republicanism, stretching back to Franklin’s Benjamin Franklin’s 1783 essay “Reflections on the Augmentation of Wages, Which Will Be Occasioned in Europe by the American Revolution.”

And, why is it that Alexander Hamilton is repeatedly smeared a mere tool of rich patriarchal elites, but we seldom hear of Hamilton’s argument that banking is largely a public utility and ought be regulated as such; or Hamilton’s scheme for corporate stock voting, in which no one would be allowed more than 30 votes, not matter if they owned thousands of even millions of shares? Why do we seldom hear of Hamilton’s explanation to Congress that paying only the original holders of Revolutionary War debt (instead of the admittedly unsavory bunch of speculators who had bought that debt for pennies on the dollar) “would be a bonanza for pettifogging lawyers, the courts would clog, sub rosa secondary markets in disputed debt would spread like mold, and government debt would be sucked away from productive investment into endless adjudication [and] public mistrust and hostility towards the new government would metastasize into a culture of scamming.” (Parenti, Christian, Radical Hamilton: Economic Lessons From a Misunderstood Founder, New York, London, Verso, 2020, p 161.)

“Are humans innately good or innately evil?”

Neuberger quotes Graeber and Wengrow, “Are humans innately good or innately evil?”

The answer of a republican — by which I mean someone who promotes or at least appreciate civic republicanism, not a member of today’s (anti)Republican Party) — is not one or the other, but both: humanity has a dual nature. While this nature is unchangeable (unlike sociialists and many on “the left” who believe that human nature will be thoroughly transformed by the elimination of private property), human nature is malleable. This is why the Constitution of the American republic is designed with checks and balances. The negative aspects of human nature can be corralled and discouraged by the institutional design of governments. That’s what the Enlightenment was about, as well as the prolonged and deep inquiry by Americans leading up to and during the Constitutional Convention,, and afterwards, during the ratification debates. Yes, some people are greedy, avaricious, power hungry, and some even narcissistic to some degree or other, but people are also intelligent, compassionate, and desirous of doing good (see Ian Welsh yesterday, Lazy V.S. Uninterested & Quiet Quitting, or Thorstein Veblen’s explanation of why most people want to do good work in Veblen’s 1914 book, The Instinct of Workmanship and the State of the Industrial Arts.

AND, the positive aspects of human nature can be encourage and nurtured by governments. in an explicit repudiation of the laissez faire ideas of Adam Smith and the British, Hamilton emphasized the importance of having active government interests and investment in developing and promoting new knowledge and technology. In his December 1791 Report to Congress on the Subject of Manufactures, Hamilton wrote:

“The left” misses this crucial point about the structure of government Hamilton helped design. Rather than the Marxist model of the means of production determining the political superstructure, what actually happens under Hamilton’s system is government support for new science and technology creates new means of production. The machine tools and machining techniques developed at the Springfield Armory after the War of 1812, became the basis for the manufacture of interchangeable parts, laying the foundation for industrial mass production. In 1843, Congress directly funded Samuel B. Morris’s development of the telegraph. In the Civil War era, it was US Navy research that introduced the science of thermodynamics to steam engine design and created the profession of mechanical engineering. In the 1930s, the Bonneville Power Authority and the Tennessee Valley Authority promoted rural electrification. Computers come entirely out of the USA government research during World War Two to create calculating machines for artillery and naval gunfire ballistics, cryptography and code breaking, flight simulation, the physics calculations of the Manhattan Project, and more. All the underlying technologies of today’s cell phone and smart phones were originally developed in government research programs. The three major developments in aerodynamics of the post war-period — the area rule, supercritical wings, and winglets — were developed by a government scientist named Richard Whitcomb using the wind tunnels at the NASA Langley Research Center. These are just a handful of the hundreds of examples I know of in which federal government sponsorship and funding fundamentally altered the means of production.

Anthony. Wow. I learned more in your comment than in the referenced article itself. The meaning of the terms has certainly changed – much of which is due to the same money power also controlling much of modern mass media which influences our understanding. Much appreciate the juxtapose of the Fromm and Lincoln quotes on labor vs. capital and the reminder how Hamilton has been “smeared”. My political science education in the 1970’s taught that “politics is a circle”. Interested readers can learn more by doing a search of this term. This is a better way to look at politics IMO than the dominate left-right characterization.

I may be commenting too late to be relevant, but I’ve been thinking about this overnight. It seems to me that the United States and its “rules-based international order” is an example of “There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

The US asserts the right to define who is in which group, and is attempting to punish Russia for refusing to accept these assertions. The people of the Donbass, dying by the thousands since 2014 from Ukraine’s shelling of their cities: out-group. Ukraine, far-right factions of which are killing wantonly: in-group.

We are seeing the rest of the world starting to refuse to accept this diktat. And we are seeing signs of change here inside the US, or at least awareness. Change is required. I hope the path does not become more bloody.