By Kenneth Rogoff, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics Harvard University. Originally published at VoxEU.

After decades of building at a breakneck pace, the stock of real estate in China is now quite large for what is still a lower-middle-income country. Studies of the country’s real estate industry tend to focus either on national aggregates or on the largest ‘tier 1’ and ‘tier 2’ cities. This column uses new data to show that China’s ‘tier 3’ cities, which account for more than 60% of its GDP and about 50% of the market value of its housing stock, seem to be the major locus of overbuilding problems that very recently have been spilling into China’s construction companies.

For all the recent attention paid to the outsized share of real estate and construction in China’s GDP, the more fundamental issue is that the sector has been racing ahead for several decades now, so much so that China already has, or is nearing, comparable square meters per capita of housing to many wealthy advanced economies. If real estate investment is running into diminishing returns, the implication is that the sector may need to shrink significantly over the coming decade, potentially exposing vulnerabilities in finance, government revenue, and employment. A fundamental question, however, that has only been touched on in the academic literature, is how the allocation of housing and construction imbalances extends across different regions, and how this might matter for any subsequent adjustment. Regional disparities may also help explain why the apparent health of the real estate sector in the largest and most prominent cities, where the data are easier to obtain, may not be representative of a large fraction of the country.

There have been a number of important papers on China’s real estate industry over the past decade, but they generally focus either on national aggregates, or on the largest ‘tier 1’ and ‘tier 2’ cities (e.g. Fan et al. 2015, Chen and Wen 2017, Glaeser et al. 2017, Chang and Xiong, 2018, Liu and Xiong 2020.) Building on earlier work on China’s growing real estate problems with Yuanchen Yang (Rogoff and Yang, 2021a, 2021b), we develop new data that allows one to analyse imbalances by city tier (Rogoff and Yang 2022). We show that the problems are much more acute in in the generally smaller and lower-income tier 3 cities. Tier 3 city real estate has been much less studied than real estate in the wealthier and more prominent tier 1 and tier 2 cities. Most previous discussion has been largely anecdotal. Nevertheless, China’s tier 3 cities account for more than 60% of its GDP and about 50% of the market value of its housing stock (70% by square meters living space); Tier 3 cities very much seem to be the major locus of overbuilding problems that very recently have been spilling into China’s construction companies.

The problem in China is not simply the size of the real estate sector, which for 2021 has direct value added of 11.8% of GDP but, including direct and indirect final demand, accounts for 25.4%. Obviously, should the real estate demand contract, say, because of slower future growth in China, the knock-on effects to GDP could be quite substantial, depending on how easily resources could be shifted to other sectors. In fact, the larger issue is that after decades of building at a breakneck pace, the stock of real estate in China is now quite large for what is still a lower-middle-income country, with per capita floor space per capita comparable to France and Germany.

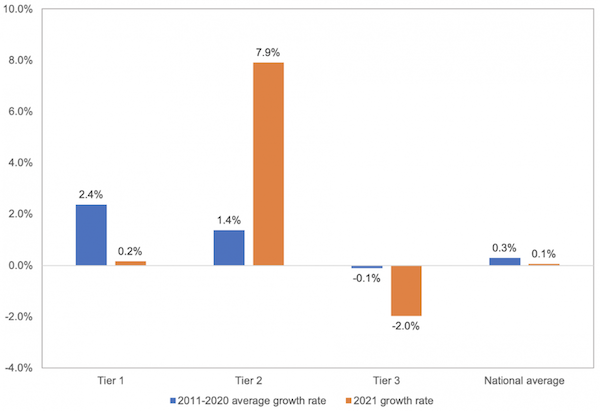

The buildup of housing in tier 3 cities, which we show is matched by commercial real estate and infrastructure construction, may have been an attempt to fight Zipf’s law; in most countries, this leads to having the largest cities absorb an outsized fraction of population and economic activity. However, the fact that the tier 3 cities have actually been collectively losing population as the tier 1 and tier 2 cities have still been gaining suggests that the attempt to “build it and they will come” (to quote the 1989 American movie Field of Dreams) has not been successful. Real estate imbalances are so significant that they are likely to weigh on growth even if they do not lead to financial crisis (Rogoff and Yang 2021a), but of course financial stress is a potential multiplier.

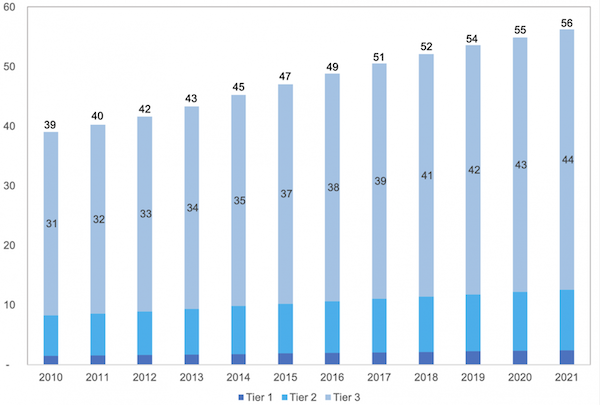

Figure 1, based on the annual data of housing stock by city tier we construct, shows the outsized weight of tier 3 cities in construction.

Figure 1 Total housing stock by city tier (million square metres)

Sources: Official website of National Bureau of Statistics of China, China Statistical Yearbook, 2010 Chinese National Census, 2020 Chinese National Census, 2010 Chinese Provincial Censuses.

Notes: The label in the centre of the bar indicates the number for tier 3 cities. The label at above the bar indicates the total number.

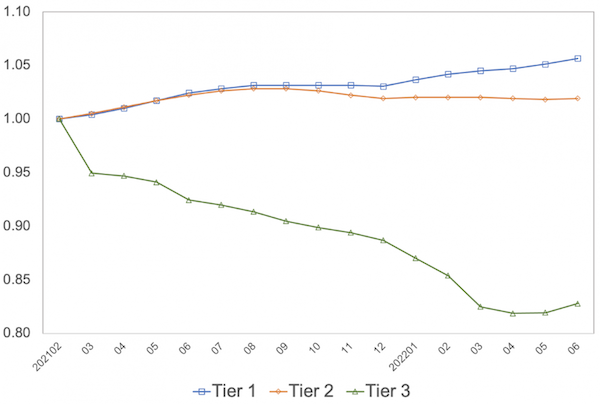

Although China does not publish statistics on housing price developments for most tier 3 cities, it does publish price indices for tier 1 and tier 2 cities, as well as for a national average. Making use of our calculations on the size of the housing stock in each of the groupings, we are able to infer price developments in tier 3 cities. As Figure 2 illustrates, recent prices have been much weaker in tier 3 cities compared to, say, the tier 1 cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou), consistent with our observations on demand and supply.

Figure 2 Housing price change by city tier

Source: Official website of National Bureau of Statistics of China

Notes: The month of February 2021 is used as the base month and the indices measure cumulative change relative to the base month.

Population outflows, compounded by a rapidly ageing overall population, point to a declining housing demand in the foreseeable future, especially for tier 3 cities. Until now, tier 3 cities have kept adding more homes despite already spacious per capita residential floor space. It is true that the real estate industry can shift away from construction of new homes and office buildings to replacement. In fact, if, following the central UN population projection estimates for China, the demand for new urban housing declines by about 3% annually through 2035, then replacement needs will account for 60% of construction. However, given that much of China’s urban real estate is relatively new, built after 2000, this will still require a considerable downward adjustment in industry size, with knock on effects to the economy.

Figure 3 Population growth by city tier

Source: Official website of National Bureau of Statistics of China.

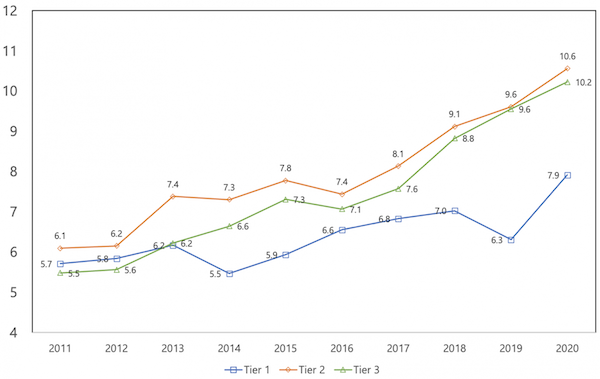

One of the key measures of distress is the number of unfinished construction projects, which has been expanding as demand shrinks and construction firms have difficulty both completing projects that are presold and offloading projects that are not. There has been much discussion of this recently in the press, but Figure 4 gives a concrete quantitative measure – the ratio of housing under construction over housing completed, which reflects the scale of uncompleted buildings relative to the existing building capacity. A typical real estate construction project, which took five to six years to be completed in the early 2010s, would take more than ten years now and run the risk of being left unfinished. As the figure illustrates, the problem is acute not only in tier 3 cities, but also in tier 2 cities.

Figure 4 Housing under construction versus housing completed by city tier

Source: Official website of National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Commercial real estate problems are quite parallel to housing. Although we are not able to produce similarly complete disaggregated data on infrastructure, we do have provided estimates for a number of important subcategories. For example, despite the fact that tier 3 cities account for roughly 60% of national GDP, they account for 88% of all roads and 92% of new road construction; the same is true for pipelines. China famously has the world’s largest high-speed rail system and continues construction at a rate that far exceeds passenger miles, particularly in the large share devoted to tier 3 cities.

All of this helps explain the apparent disconnect that persisted for some time between aggregate estimates suggesting ‘peak China housing’ (Rogoff and Yang 2021), and journalistic accounts of still strong price performance in the large cities. Today, there is much broader understanding that China’s real estate sector is in trouble, but the important point we make here is that epicentre is in the tier 3 cities, which are collectively far more important than is commonly realised. Lastly, although it is true that the Chinese government has enormous leverage over real estate through financial regulation and myriad other instruments, it is wrong to argue the current malaise is simply due to excessive tightening of lending regulations. After the heady days in which construction was at the core of China’s growth strategy, decreasing returns are setting in just as they did for Russia railways and steel plants in the 1970s, and for Japanese infrastructure in the 1980s. Given the many factors pointing to slower long-term Chinese growth, including adverse demographics, excessive centralisation, slowing benefits from catching up with Western technology, not to mention the costs of transition to a low-carbon economy, it appears that a major adjustment is needed in Chinese real estate, particularly in the tier 3 cities.

One of the strengths and weaknesses of the Chinese system is the financial independence of its provincial and county level governments – this has allowed for a very competitive and successful system of regional development. The houtou system, while cramping for the biggest urban areas, has also prevented depopulation in many poorer areas. China has managed a remarkably even level of urban development over the past 30 years.

However, this may prove an Achilles heel at a time of oversupply of housing. Local government finances are heavily dependent on property sales and related taxes. This is having the effect that already strong regions/cities are finding it much easier to deal with the myriad financial problems around the popping of the bubble, while in poorer regions the impacts are self reinforcing. As poorer local governments struggle to pay the bills or rescue local businesses, the areas lose jobs and political influence, potentially leading to a spiral of decay. For the weakest Tier III cities, there maybe no way out of this spiral. Add in a sudden demographic shift with fewer young people, and its likely to get even worse in the longer term.

The solution is obvious – more active intervention by Beijing. But identifying a problem and acting on it are not the same thing. There seems little evidence of any momentum behind the type of fundamental change to China’s tax/expenditure system that would be required to balance things up.

For context – there’s this nice American girl fluent in Mandarin that AFAIK has spent last couple of years travelling China and putting videos on the Internet. Commenter ChrisRueCon had mentioned her some time ago and I spent a good few evenings watching her content since (which I recommend).

Here’s her video relation from a small town in China that is said to be an “18th tier city”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uPUF7P5enck

I enjoy that type of video – it replicates the type of nosing around I love to do when travelling. Its a little like the ADVChina guys used to do before they went off the rails. I do find the lack of analysis really irritating though, with her formidable mandarin skills she would be able to say a lot more about the how’s and why’s of what she’s seeing but i guess there isn’t a market for that.

Its unfortunate that while that town looks lovely, and seems to have a much better local government than most (that attention to detail with public space is quite rare in China in my experience), its most likely that the funding is directly tied to all those apartments being built, and they are almost certainly a major off-shoot of the bubble. Reminds me a little of the jaw-dropping residential developments (commercial estates and personal homes) built in Ireland in little remote towns in Ireland during the Celtic Tiger. Many are still very sad looking now.

Really nice find, thank you!

Thanks. This is a really important topic. In a similar vein, I’ve tried to pull together a picture of the (economic) geography of the Chinese auto industry, without much success. Provincial governments and major cities have all attracted auto producers, even the island province of Hainan (the exceptions are Tibet and a couple other poor, remote areas). So China’s decentralization, and the power of local governments to counteract government policy that sought to concentrate production stand out.

Most New Energy Vehicle sales are in Tier I and the larger Tier II cities, but I don’t have data on the overall market by city tier. I do have data on suppliers, which account for most of the industry’s employment. They are clustered above all in the lower Yangtze area, and more generally in an “auto zone” of about comparable size to the “auto alley” and “auto corridors” of Europe and the US (work on those by Thomas Klier and James Rubenstein). But seating and instrument panel plants – bulky and vehicle-specific – are near assembly plants, as in North America and Europe.

To tie this back to the article, we need to know more of the economic geography of China, particularly as the overall population starts to fall, which will amplify many geographic disparities.

The hukou system hasn’t been a real constraint in recent years, except for migrant workers. The main constraint on population growth in Tier 1 cities is still housing. That problem should be familiar to anyone looking at housing in Vancouver, New York City or SF Bay Area.

How much of the housing in the top tier cities is investment housing, not unlike what has been going on with in Vancouver or Toronto? How many investors are there for Inner Mongolia or the rust belt Northeast? China has its own PMC, where they cluster not just along the coast but in the Yangtze river basin.

May I gently point out that if China is building high-speed rail connecting Tier 3 cities at breakneck pace, then these are not really Tier 3 cities but suburbs of Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities? And their overbuilt condition is just future provision.

The economic geography needs to be tied to physical geography and the cities decomposed into travel pattern clusters.

My understand is that Tier 3 is a crude measure based on population size.

I would also point out less gently that Rogoff has form in pushing shoddy analyses with basic spreadsheet errors in pursuit of ideological hypotheses. See Reinhart-Rogoff GDP-debt “findings”. Criticising China for delivering (literally) concrete material benefits for its citizens seems to be a reskinning of his previous anti-state nonsense. The tell is his pearl-clutching at the temerity that the Chinese might aspire to better housing standards than the French or Germans!

In his defence, I would note that quality us not quantity: I opener the window in a five star hotel in Chongqing in 2001 and the handle promptly dropped thirty stories to the ground. I hope nobody was underneath….

Your point about HSR is a very interesting one. The research on HSR indicates very mixed results. What seems to occur in China (and this follows patterns elsewhere) is that when cities of roughly equal strength are connected, and journey times become ‘reasonable’, then there is an important agglomeration impact which significantly benefits both cities. Unfortunately, when struggling cities are connected to more prosperous ones, the benefits are one-way – the big city gets a bigger market/labour source, the weaker area sees itself turned into a commuter town. This replicates many studies of the extension of railways in the 19th Century (it used to be called the Appalachian Effect, a term I remember from my student days but seems to have fallen out of use).

It should be noted though that ironically enough, China’s railways are probably too slow to have a real national effect. Super high speed railways like Japans chuo shinkensen are probably a better option for some of the Chinese Tier 1 cities. China is very, very large, so most well off Chinese opt for flying for many intercity trips, and poorer Chinese can’t afford HSR.

I’ve commented before that China, along with quite a few countries, has heavily overinvested in HSR to the point where it is potentially a significant drag on some economies – if rumours are correct, some of the fare revenue from some newer lines in China can’t even cover their electricity bill. HSR is very beneficial in very specific corridors (think Paris/Bordeaux or Tokyo/Osaka or, for that matter, Beijing/Shanghai), but are probably not worth the direct investment in most others. In my opinion, the evidence points to urban metros and dedicated goods railways as generally better bang for the buck investments for growing economies. Ironically, this is an area the US does better than China – thanks to 19thC bubble economics it has a far better network of goods transporting railways than China.

As for hotel handles, I had very similar experiences in China. I’ve always been very careful in turning any handle or switch in a new hotel there, you never know what will come off, or come out. I’ve been in one or two Mao era hotels built for the cadres and they were notably better built than many of the most up to date, and expensive hotels. I’m told its improved a lot the past few years, since my last visit.

Yes, becoming a high speed rail dormitory town is the likely fate of these Tier 3 cities but the same can be said of much of the Tokaido and Chuo lines in Japan or of anywhere peripheral on a lovely integrated transport network.

However, we should remember that:

& we are talking about big cities by any other standard, 1m+ populations, so even a subdued local economy may be quite a well developed place.

– I seem to remember the Chinese definition of a city is curious and bureaucratic. It either includes or excludes rural land within its confines. Do you remember the issue, PK? It gas been discussed in NC along with Hukou

This is why we need to see the actual linkage data. There is a difference between a smoothly dense and dispersed conurbation like the Ruhrgebiet (and seemingly the Donbass) and the Liverpool-Manchester-Leeds and the Tokyo-Yokohana-Nagoya conurbations and somewhere like Spain with urban oases amid the plains. Some of these small cities may be distinguishable only to their local governments rather than from space!

(Trainspotter point: the shinkansen is optimised for short distance high-speed running (single dense population arc) with fast braking and acceleration whereas the TGV is optimised for long-distance running (empty France) with slow braking and acceleration. China chose the shinkansen as the technology it, er, flattered….)

I’m not sure about the precise definition of a city in China – in much of China the terrain is such that cities are very tightly contained in valleys, so they have nice natural boundaries – there are exceptions of course. Its not quite like Japan where cities are essentially bureaucratic inventions (I always find it ironic that the USAF failed to destroy the city of Kokura with a nuclear bomb because of bad visibility, but it was wiped out of existence years later with the swipe of a pen by some Tokyo bureaucrats). I’ve read very contradictory things about hukou, not least because I think the figures get fudged by local governments according to whatever message they are trying to get across at any given time. But one thing is sure and that is that most Chinese cities have excellent internal public transport nodes, they rarely stinted when it came to integrating their transport systems. Even the Taiwanese screwed up a little with their HSR in that they avoided the centres to make it cheaper, but this led to the stations being hard to access.

You are right of course that it makes a huge difference if your city has a nice dense node, or just sprawls, which is one of the reasons why HSR would probably never work for so many US cities.

Thats an interesting point about the French vs Japanese systems, although I was told (possibly in a self serving manner) by a number of French railway engineers that they refused to sell the TGV to China as they knew it would be reverse engineered, as indeed they did with the Shinkansen. The French are probably the best when it comes to not getting ripped off by the Chinese – so far even Airbus has kept most of its technical secrets. It takes a mercantilist to know a mercantilist.

As I thought, there was a bureaucratic. Wheeze. China reclassified rural areas as part of a city (no doubt local govt wanted expansion) but various measures then omit the peasant from the urban population and they cannot get urban registration.

https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/95_02_01.pdf

I think the outcome is that the rural population is stuck with no hukou, being in the city but not if it. They can wait for industrisation or flee to the nearest place as an undocunented migrant.

Thanks for that link, very interesting. A good reminder to be very cautious when using terms like ‘city’, ‘urban’ ‘rural’, etc. They are almost always arbitrary definitions. There are still plenty of ‘rural’ areas in Asia that probably have higher densities of population than LA or Phoenix. For that matter, parts of rural Ireland in the early 19th century had densities greater than a typical modern US suburb.