Lambert here: As the holiday season begins….

By Ania Jaroszewicz, Postdoctoral researcher Harvard University, George Loewenstein, Herbert A. Simon University Professor of Economics and Psychology Carnegie Mellon University, and Roland Benabou, Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Princeton University. Originally published at VoxEU.

The economic consequences of receiving essential help from a friend, relative, or colleague can be momentous. But there are countless situations in which people don’t ask for help or, conversely, in which people with the ability to help don’t offer it. This column examines the factors that determine the offering, asking, and granting of help. Asking entails the risk of rejection, which can be painful, generating a trap wherein those in need hope – but don’t ask – for an offer, while willing helpers wait for a request, resulting in significant inefficiencies.

Imagine a not unusual COVID scenario. A friend who lives alone catches COVID, and you suspect she would benefit from some assistance – perhaps a grocery or drugstore delivery. You are very busy and would prefer not to help, but suspect she might know that you know she would benefit from it. If you knew that she knew that you were aware of her need, or if she explicitly asked for help (in which case you would clearly know she needed it), you would certainly help. However, she fails to ask because she is afraid to. If she asked and you turned her down, she would be devastated by the rejection. Although asking for help might seem like a trivial matter, as suggested by the common exhortation “It can’t hurt to ask”, the example illustrates that asking for help and providing it often involve complex calculations. In particular, it very much can hurt to ask, because asking exposes one to the possibility of a painful rejection.

The economic consequences of receiving needed help – or not – from a friend, relative, colleague, professor, or supervisor, can be momentous. A person struggling financially who does not get a loan from a relative may instead take out a costly payday loan. A student who does not get help from his classmates or adviser may fail an exam, jeopardising his educational future. In thinking about how such helping interactions may (fail to) occur, we look to two sources: the demand side (the decisions of people in need to either ask for help or not), and the supply side (the decisions of potential helpers to either offer help proactively or not, and to accede to a request or not). Many of us can think of situations in which we were in need but did not ask for help, or conversely when we had an opportunity to offer help but chose not to.

Factors That Determine Asking and Giving Decisions

Why don’t people in need ask for help? Moreover, if potential helpers would give if asked (which they often do), why don’t they offer proactively? Social scientists have proposed a number of explanations for asking and giving behaviours. On the asking side, people may not ask because they fear revealing that they are needy or incompetent (Tessler and Schwartz 1972), or because they don’t want to be indebted to others (Greenberg and Shapiro 1971). On the giving side, the main question has been not why people don’t want to give (since giving is costly), but rather why many do give. Answers proposed include altruism (of different types, see e.g. Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. 2017), social and self-image motives (Bénabou and Tirole 2006), and reluctance to violate expectations of helping (Dana et al. 2007, DellaVigna et al. 2012).

As our opening example illustrates, both offering and asking decisions can hinge on uncertainties that are inherent in many interactions. A person in need may wonder, “How much does this potential helper care about me and our relationship? Why haven’t they offered? If I ask them, will they say yes?” At the same time, the potential helper may be wondering, “Does this person actually need my help? Do they know that I know that they need help? Are they going to ask me? Will I look selfish if I don’t offer?”

In a new paper, we develop a game-theoretic model capturing interactions between a person in need and a potential helper (Bénabou et al. 2022). The types of help the theory applies to are very broad, ranging from material resources like money, effort, and time (e.g. housework assistance, guidance on how to complete a task at work), to actions that signal caring about someone, such as accepting a dating invitation or ceasing a behaviour they dislike. The theory is especially applicable to individuals who know one another (friends, family, colleagues) but also extends to relative strangers and to relationships between organisations and their employees, who often hesitate to ask for a raise, promotion, or accommodation (e.g. Babcock and Laschever 2009).

The Model

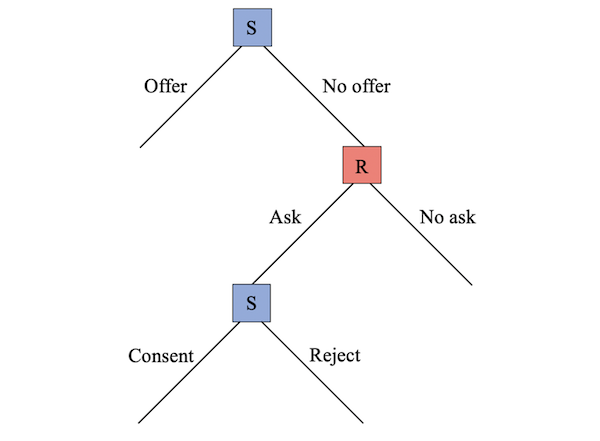

There are three stages, shown in Figure 1. First, the potential helper can either offer help proactively or not. If they offer, the help is always accepted, or at least the cost of helping (cancelling a meeting, buying groceries) is paid. If they do not offer, the action proceeds to the second stage, where the person in need can choose to ask. If they do not ask, the game ends, with no help given. If they ask, it enters the third stage, in which the potential helper can consent to or reject the request.

Figure 1

Note: The game tree. In this game, S stands for Sender, the person who is able to help; R stands for Receiver, the person who is in need and thus might receive help.

There are two sources of uncertainty, and the actions of each person provide information to the other party that helps resolve this uncertainty. The potential helper is uncertain about the other person’s need for help, and the person in need is uncertain about the potential helper’s generosity or concern for them. Besides the material costs and benefits of helping, both parties may benefit from the potential helper being perceived as generous. First, and most importantly, the person in need cares about feeling valued or respected by the potential helper. The potential helper, in addition, may care about being seen as a generous person.

The crux of the model is that in the absence of an ask, the lack of helping can be attributed to one of two things: the potential helper’s selfishness, or her unawareness of the need (or its severity). Thus, while the lack of an offer is not good news, it does not sting too badly, as there is a plausible excuse for it. When an ask occurs, however, it conveys substantial information about the asker’s situation, so the ‘ignorance of need’ explanation is eliminated. A failure to help can now only mean that the potential helper doesn’t care much about the person in need, or value the relationship.

What This Gets Us

The model generates many insights. First, a person may not ask for help even if their need is severe and the potential helper would very likely agree to help if told about it. This form of information aversion occurs because being rejected hurts more than being consented to feels good: receiving help is good news and makes a person feel more valued, but the negative inferences from a rejection can be much more devastating. Moreover, paradoxically, because getting rejected for a very serious need hurts more than getting rejected for a minor one, in some cases the needier a person is, the less likely they are to ask.

The model also explains why a person may not offer help proactively, even if they would be willing to help in response to an ask. Offering help is risky: to be credible, an offer must involve some commitment, which means giving up the option to fully ascertain the need before deciding to help or not. Examples include taking time from work to make oneself available, or, in our COVID case, proactively bringing a home-cooked meal or groceries without knowing how useful or appreciated that will be. Even a relatively caring person may then prefer to wait for an ask, rather than pledge or deliver help while unsure of whether the benefit will justify the cost. Importantly, the more caring the person, the more willing they are to take that risk, which also means that not receiving an offer is already bad news about the other person’s generosity (though typically less hurtful than an explicit rejection of an ask).

The parties’ equilibrium behaviours resulting from this two-sided private information can generate important inefficiencies, such as what we call a ‘waiting trap’. Suppose that a potential helper does not offer help proactively, to avoid the risk of helping ‘unnecessarily’, choosing instead to wait for an ask. As explained, the person in need should then revise downward their view of the potential helper’s level of caring. This pessimism, in itself, may discourage asking. In such a case, both parties will wait indefinitely for the other to make the first move, and a helping interaction that both would have wanted to occur (under common knowledge) will fail to materialise.

Why It Matters

Asking and giving decisions can significantly impact the economic and psychological outcomes of both sides (e.g. Aknin et al. 2013, Andreoni et al. 2010). A better understanding of what underlies these behaviours also delivers insights about how to improve these interactions. For instance, our analysis shows how organisations can benefit from fostering a ‘culture of asking’, in which no proactive offering should be expected (rendering the lack thereof uninformative), and expectations are coordinated instead on people in need making the first move and asking for help. Another application is the use of intermediaries and platforms to convey both requests and responses (e.g. GoFundMe and other crowdfunding campaigns, or even apps like Tinder). Besides reducing transactions costs, these serve as devices that facilitate asking by dampening the visibility and salience of rejections.

like with the voting thing…smaller polities.

during my wife’s initial month long emergency phase in the hospital, fall of 2018…our bank account kept having money appear in it.

bank manager there is wife’s aunt…so folks would hand her an envelope, and she would never tell who it was.

it felt weird, i must admit…as someone who had never felt like i belonged anywhere.

when i finally brought wife home, local ladies…mostly her teacher colleagues…organised a “meal train” on faceborg…boys would get a call or notice…often through my MIL, who sits at a nexus of the jungle drum network…to pick up dinner. Usually “shepherd’s pie” or “tater tot casserole”, and the like(“white people food”,lol…and every single dish had canned corn in it).

all that started up again once we were in hospice.

after she died, i kept getting little cards indicating some anonymous(usually) person or family had donated x amount to the local cancer society(who had helped us with gas and hotel, throughout).

and random money kept showing up in the bank account for 2 months after she died…$50 here, a couple of hundred, there…

all of this, because wife was respected and loved by the polity…which is small enough to have those kinds of relationships.

we never asked for any of it.

and that’s how it should be.

of note…many of the non-anonymous money things were from folks who we didn’t really gel with…bvut who apparently felt an obligation, somehow, to do their part…there was apparently some social mechanism going on behind the scenes, and likely within various groupings/cohorts that more or less enforced this adherence.

i was thoroughly overwhelmed by all of this largess…didn’t expect it, and didn’t know how to respond, save with humility and gratitude…

and , like with voting and the check on the behaviour of the bank presidents i often mention, i’m uncertain how to scale up these things to larger, less tight-knit polities.

we’re an anomaly, out here…isolated, historically, from the rest of the world….a holdover from the days when travel and comms were hard(40 miles to nearest other town, in other counties(days ride on horseback))…small population(4500 in whole county) and deep and intertwined relational connections(i can’t for the life of me get my head around just who all i am related to,lol)

(ive put the word out that once i get done with all the catching up from almost 4 years of neglecting my doings, and get to a relatively stable place, i’d like to put back…and cook for folks who need it(former chef, after all)…but i’m not on FB,lol…)

Amfortas: Thanks for this story of the network of obligation, and how obligation isn’t always perceived as a burden. All the best.

I don’t think these things scale up naturally. The polite customs, norms, and social enforcement all depend on everyone being somebody’s third cousin or brother-in-law.

Social credit scores are a totalitarian way of trying to enforce this at scale.

yeah.

i think about the scale problem with regards to what works in this place(and has evolved in this place) a lot.

but federalism and subsidiarity might get close…and maybe without such totalitarian enforcement…however,lol…”assume a can opener”, and all.

and to be clear, this far place is not all roses and sunshine…a significant cornbread mafia, connected to some of the oldest and wealthiest sons of pioneers, with fingers in everydamnedthing, including the meth trade.

nepotism, as well as scions of said old families obtaining positions of power, so as to cover for the ugly shenanigans underneath everything.

almost all of this corruption and ugliness goes unnoticed by the genpop…which is one of the mechanisms they evolved to keep the peace.

i could go get naked on the courthouse square and yell about socialism…and the cops would carry me off, the rumor mill would swirl for a day or two, and then it would be forgotten, as if by general agreement.

that’s how it works.

if you frell up…just lay low for a few days until someone else frells up,lol.

so the corruption and nepotism and ugly predation sanctioned tacitly goes unresolved…and everyone gets to pretend that the local paper is actually a newspaper, instead of a brochure.

occasionally, some Made Man in the cornbread mafia/bidness nexus will go too far…and a few minor heads will roll, and the rumor mill will swirl for months…but then we’ll all move on, and pretend again.

regardless, the caring portions of the rumor mill structure i delineated above are very real…and that acts as a counter to the mostly ignored ugly.

Lived in small cow town in NE Nebraska county pop. 6500 (about 10x times that in cattle), now retired to small tourist town in SE Colorado po. 9500. Local corruption here dates back to Al Capone days – he literally owned a ranch here, hid various Chicago mobsters there in the 1920s – and has apparently continued in one form or another.

Much lesser local versions back in Nebraska, but I’m beginning to think as a retired old Boomer (whose lovely second marriage bumped me up a couple of tax brackets) that corruption in modern America – and western society in general – has become so routine that for us proles to expect otherwise is, well, naive at best and just plain stupid at worst.

Why did Bernie and Trump blow up the Democratic and Republican primaries in 2016? They spoke plainly, and while Trump lies like most of us breathe, he told the truth about enough shibboleths like Iraq to engage voters’ interest.

Until our fossilized political systems – from party duopoly to 50 state voting systems to campaign financing – change, we’ll continue to spiral into anarchy or worse. Suck it up buttercups! The only way out is through.

I don’t disagree with the reasoning, but I really do not see how this goes beyond standard psychology insights. I confess I did not click through to the original and it is good that economists are paying attention to psychology, but really don’t see from this piece what additional insights game theory produces.

Something to thaw people out on the holidays,

sort of a sequel to sam stone

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXbEFTv9zr0

This is really relevant to me having been in this situation recently. After my mom died unexpectedly earlier this year, my dad and I were in financial straits because we depended in part on her SS. A family member helped us out ,but I had to ask because he didn’t know what was going on.

Some people , like my dad, just don’t have the temperament to ask for larger help. It’s not stubbornness or pride-it’s just how he is. He’s a quiet person. I have to be his advocate sometimes or simply anticipate what needs to be done and do it. But not everyone has a assertive enough autistic daughter.

Asking for help sucks, but it’s better than drowning. And I’m not a ‘go quietly into the night’ person.

Anyway we’re okay now. Like Amfortas there was an outpouring after my mom’s death and I want to give back where and how I can. But sometimes there are people that you have to know really well and anticipate that they need help.

I see a straight line from discomfort asking for help to excess consumption and waste. In my younger days we owned a boat but no truck. Twice a year we had to borrow a truck to put the boat in the water and take it out. I can’t describe how uncomfortable that was for me – my issue – but the couple times people seemed annoyed caused me pain. Eventually I bought a used SUV in part to avoid asking for help. I think about this when I see the highways clogged with enormous trucks and SUVs, which I imagine are used for basic personal transportation 90% of the time.

Relatively wealthy Americans pride themselves on self-reliance, which in practice means a lot more trucks & tools out in the community than the community really needs. The recent post on tool sharing libraries struck a chord with me. I feel like, in countries with less material wealth, social networks are better developed, there are fewer trucks and tools to go around and sharing is expected. If everyone could get comfortable sharing, maybe we’d all feel a little less isolated while doing the planet a good turn?