Yves here. I sat in on a series of presentations at the Explorers’ Club on the findings of the 2007-2008 International Polar Year, an every-ten-year research project. The speakers and participants were scientists and yes, explorers who had spent a lot of time in the Arctic in addition to their Polar Year investigations. All spoke formally and in sidebar discussion about how fast and visible the warming-induced changes were.

By Matthew L. Druckenmiller, Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder; Rick Thoman, Alaska Climate Specialist, University of Alaska Fairbanks; and Twila Moon, Deputy Lead Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder. Originally published at The Conversation

In the Arctic, the freedom to travel, hunt and make day-to-day decisions is profoundly tied to cold and frozen conditions for much of the year. These conditions are rapidly changing as the Arctic warms.

The Arctic is now seeing more rainfall when historically it would be snowing. Sea ice that once protected coastlines from erosion during fall storms is forming later. And thinner river and lake ice is making travel by snowmobile increasingly life-threatening.

Ship traffic in the Arctic is also increasing, bringing new risks to fragile ecosystems, and the Greenland ice sheet is continuing to send freshwater and ice into the ocean, raising global sea level

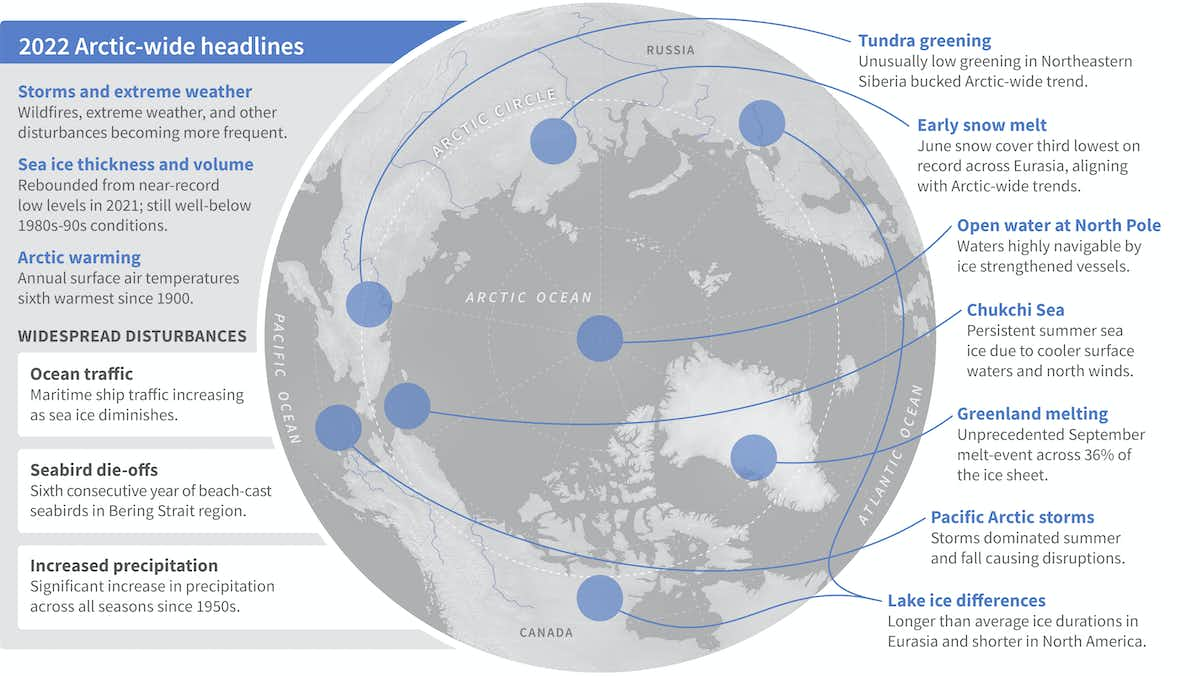

In the annual Arctic Report Card, released Dec. 13, 2022, we brought together 144 other Arctic scientists from 11 countries to examine the current state of the Arctic system.

The Arctic Is Getting Wetter and Rainier

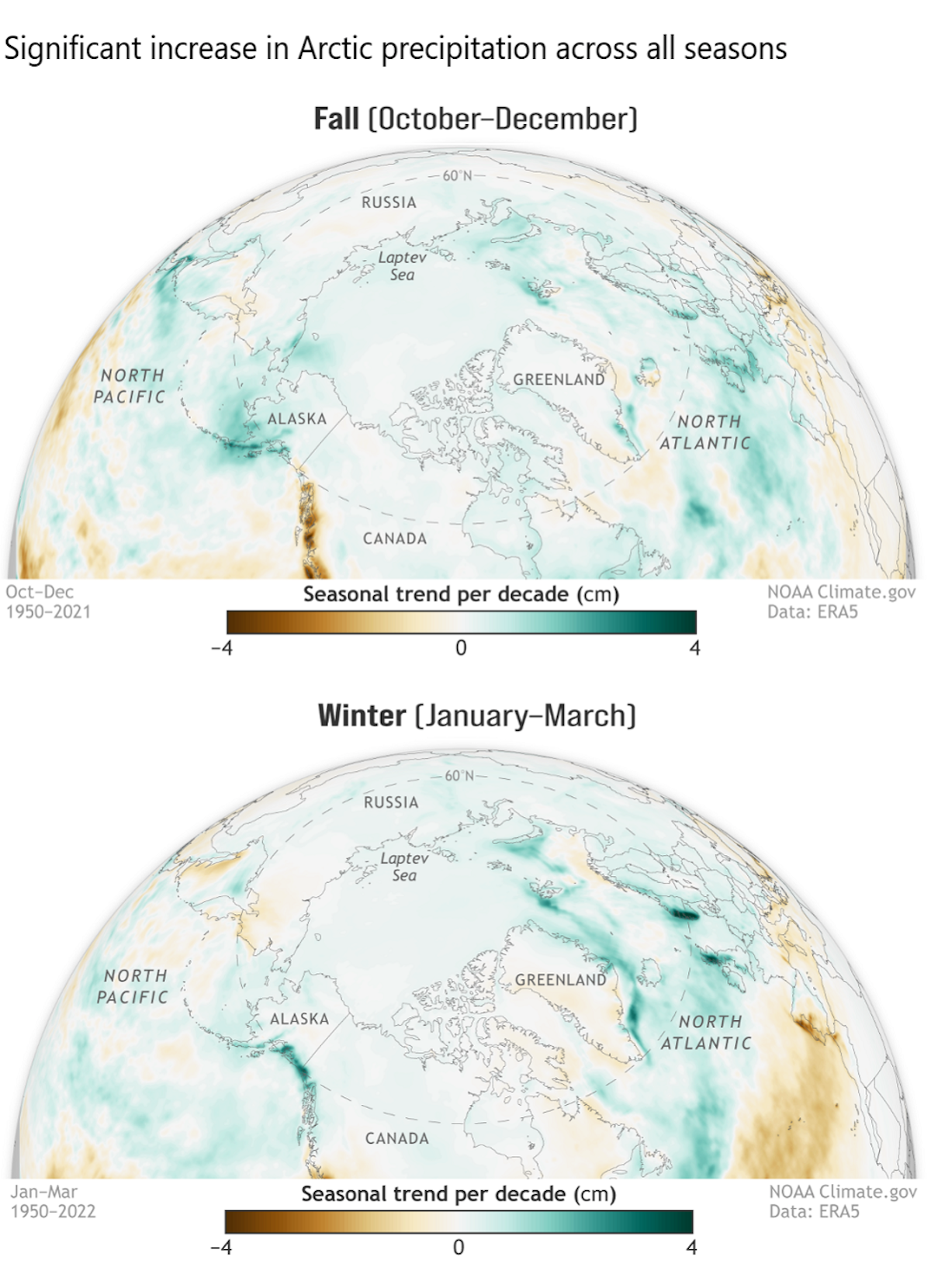

We found that Arctic precipitation is on the rise across all seasons, and these seasons are shifting.

Much of this new precipitation is now falling as rain, sometimes during winter and traditionally frozen times of the year. This disrupts daily life for humans, wildlife and plants.

Roads become dangerously icy more often, and communities face greater risk of river flooding events. For Indigenous reindeer herding communities, winter rain can create an impenetrable ice layer that prevents their reindeer from accessing vegetation beneath the snow.

Arctic-wide, this shift toward wetter conditions can disrupt the lives of animals and plants that have evolved for dry and cold conditions, potentially altering Arctic peoples’ local foods.

When Fairbanks, Alaska, got 1.4 inches of freezing rain in December 2021, the moisture created an ice layer that persisted for months, bringing down trees and disrupting travel, infrastructure and the ability of some Arctic animals to forage for food. The resulting ice layer was largely responsible for the deaths of a third of a bison herd in interior Alaska.

There are multiple reasons for this increase in Arctic precipitation.

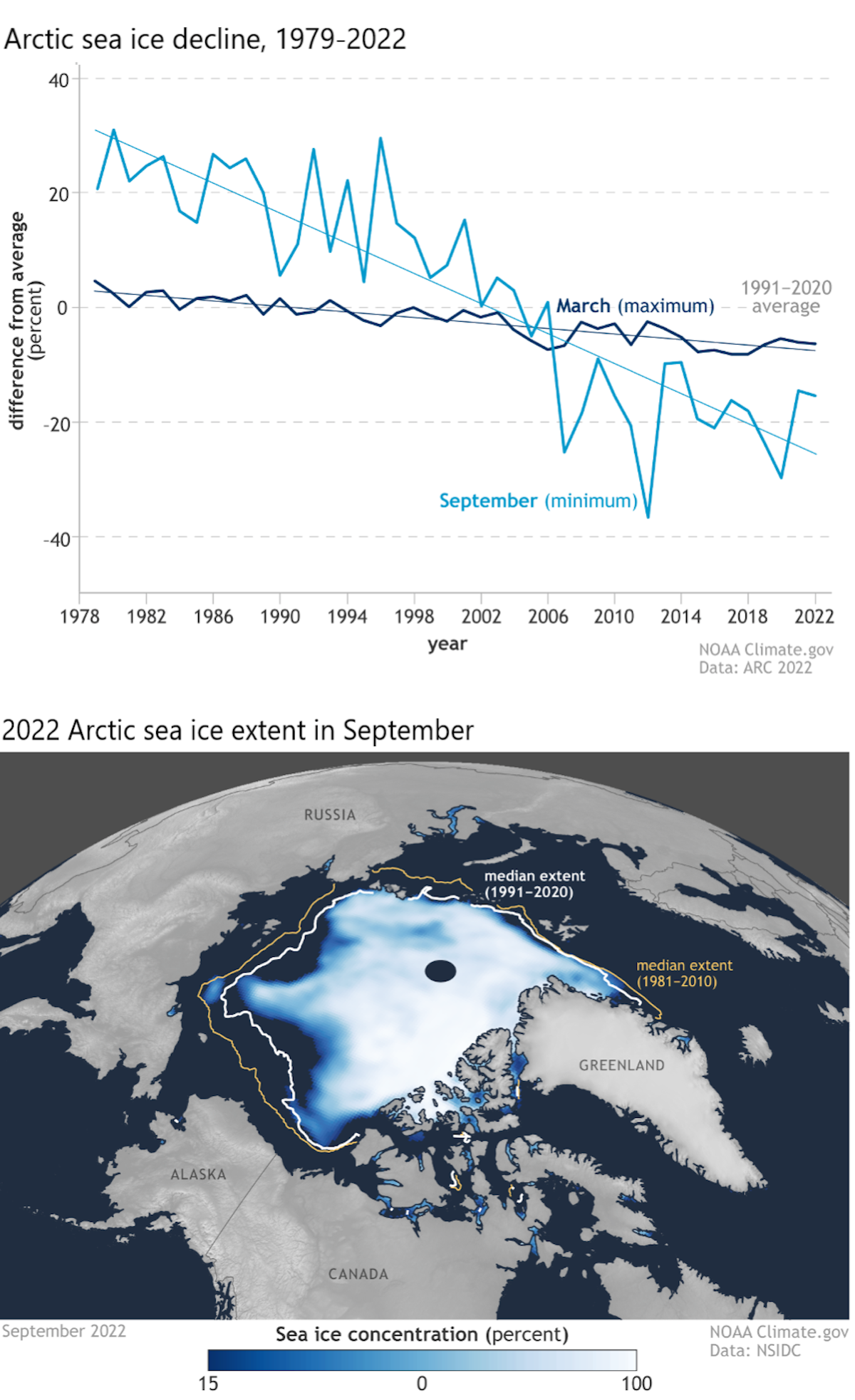

As sea ice rapidly declines, more open water is exposed, which feeds increased moisture into the atmosphere. The entire Arctic region has seen a more than 40% loss in summer sea ice extentover the 44-year satellite record.

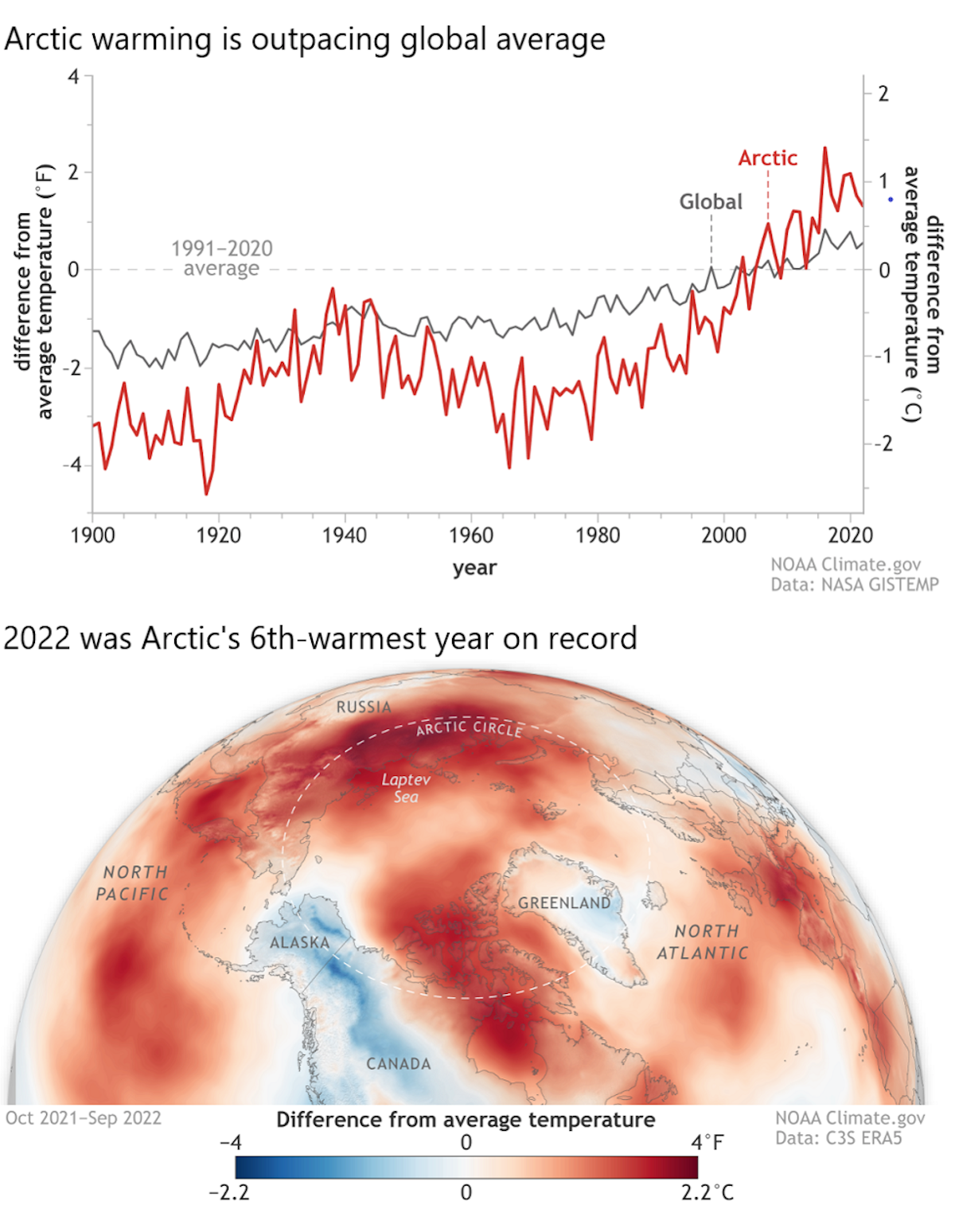

The Arctic atmosphere is also warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the globe, and this warmer air can hold more moisture.

Under the ground, the wetter, rainier Arctic is accelerating the thaw of permafrost, upon which most Arctic communities and infrastructure are built. The result is crumbling buildings, sagging and cracked roads, the emergence of sinkholes and the collapse of community coastlines along rivers and ocean.

Wetter weather also disrupts the building of a reliable winter snowpack and safe, reliable river ice, and often challenges Indigenous communities’ efforts to harvest and secure their food.

When Typhoon Merbok hit in September 2022, fueled by unusually warm Pacific water, its hurricane-force winds, 50-foot waves and far-reaching storm surge damaged homes and infrastructure over 1,000 miles of Bering Sea coastline, and disrupted hunting and harvesting at a crucial time.

Arctic Snow Season Is Shrinking

Snow plays critical roles in the Arctic, and the snow season is shrinking.

Snow helps to keep the Arctic cool by reflecting incoming solar radiation back to space, rather than allowing it to be absorbed by the darker snow-free ground. Its presence helps lake ice last longer into spring and helps the land to retain moisture longer into summer, preventing overly dry conditions that are ripe for devastating wildfires.

Snow is also a travel platform for hunters and a habitat for many animals that rely on it for nesting and protection from predators.

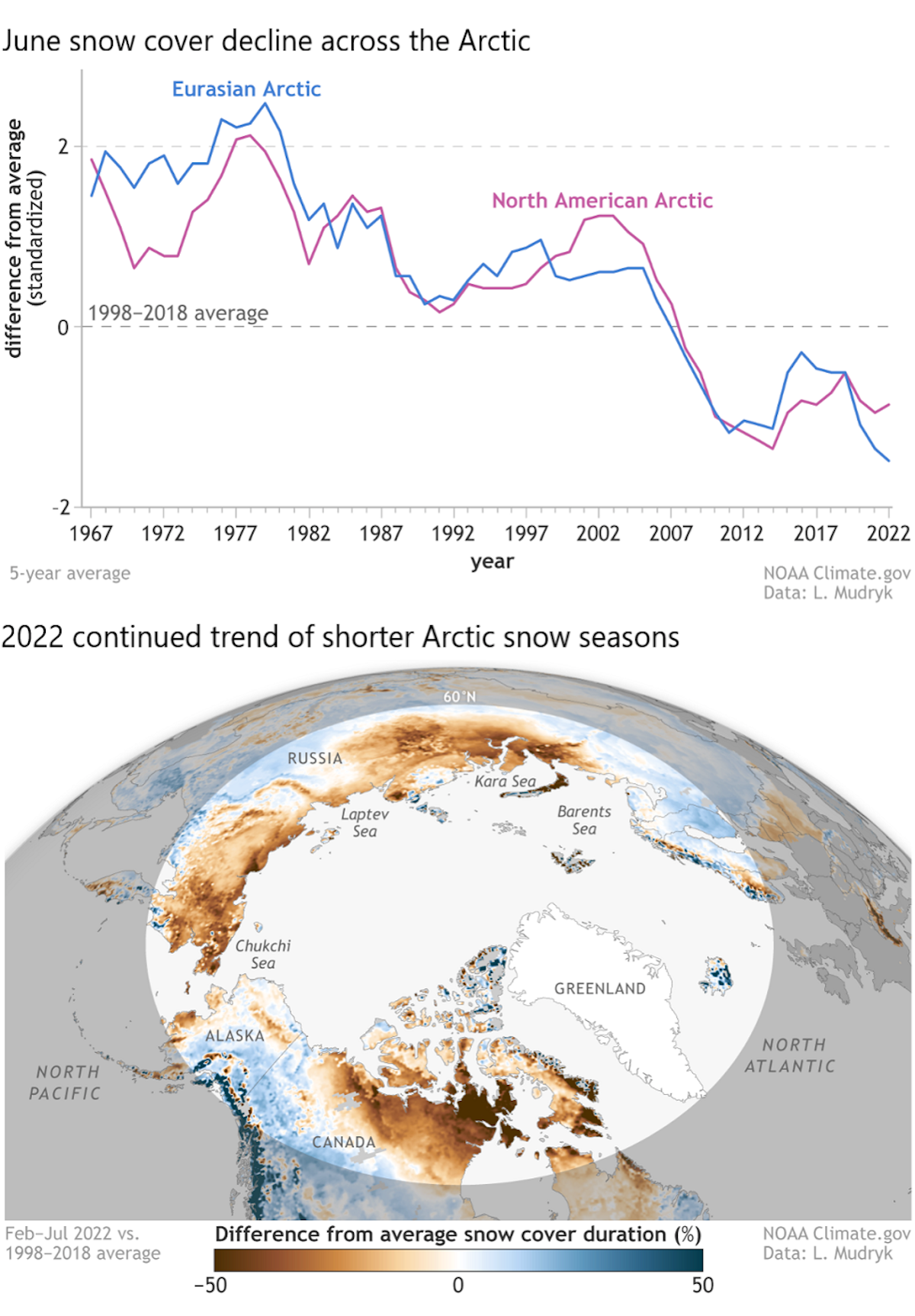

A shrinking snow season is disrupting these critical functions. For example, the June snow cover extent across the Arctic is declining at a rate of nearly 20% per decade, marking a dramatic shift in how the snow season is defined and experienced across the North.

Even in the depth of winter, warmer temperatures are breaking through. The far northern Alaska town of Utqiaġvik hit 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4.4 C) – 8 F above freezing – on Dec. 5, 2022, even though the sun does not breach the horizon from mid-November through mid-January.

Fatal falls through thin sea, lake and river ice are on the riseacross Alaska, resulting in immediate tragedies as well as adding to the cumulative human cost of climate change that Arctic Indigenous peoples are now experiencing on a generational scale.

Greenland Ice Melt Means Global Problems

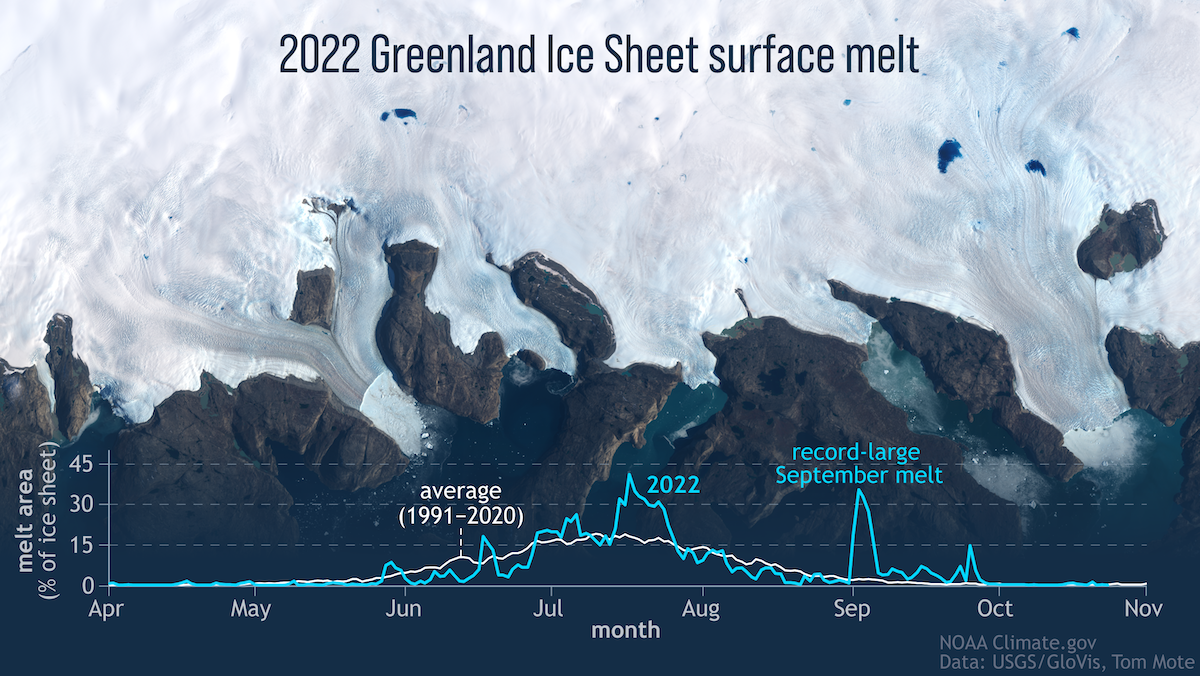

The impacts of Arctic warming are not limited to the Arctic. In 2022, the Greenland ice sheet lost ice for the 25th consecutive year. This adds to rising seas, which escalates the danger coastal communities around the world must plan for to mitigate flooding and storm surge.

In early September 2022, the Greenland ice sheet experienced an unprecedented late-season melt event across 36% of the ice sheet surface. This was followed by another, even later melt event that same month, caused by the remnants of Hurricane Fiona moving up along eastern North America.

International teams of scientists are dedicated to assessing the scale to which the Greenland ice sheet’s ice formation and ice loss are out of balance. They are also increasingly learning about the transformative role that warming ocean waters play.

This year’s Arctic Report Card includes findings from the NASA Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) mission that has confirmed that warming ocean temperatures are increasing ice loss at the edges of the ice sheet.

Human-Caused Change Is Reshaping the Arctic

We are living in a new geological age — the Anthropocene — in which human activity is the dominant influence on our climate and environments.

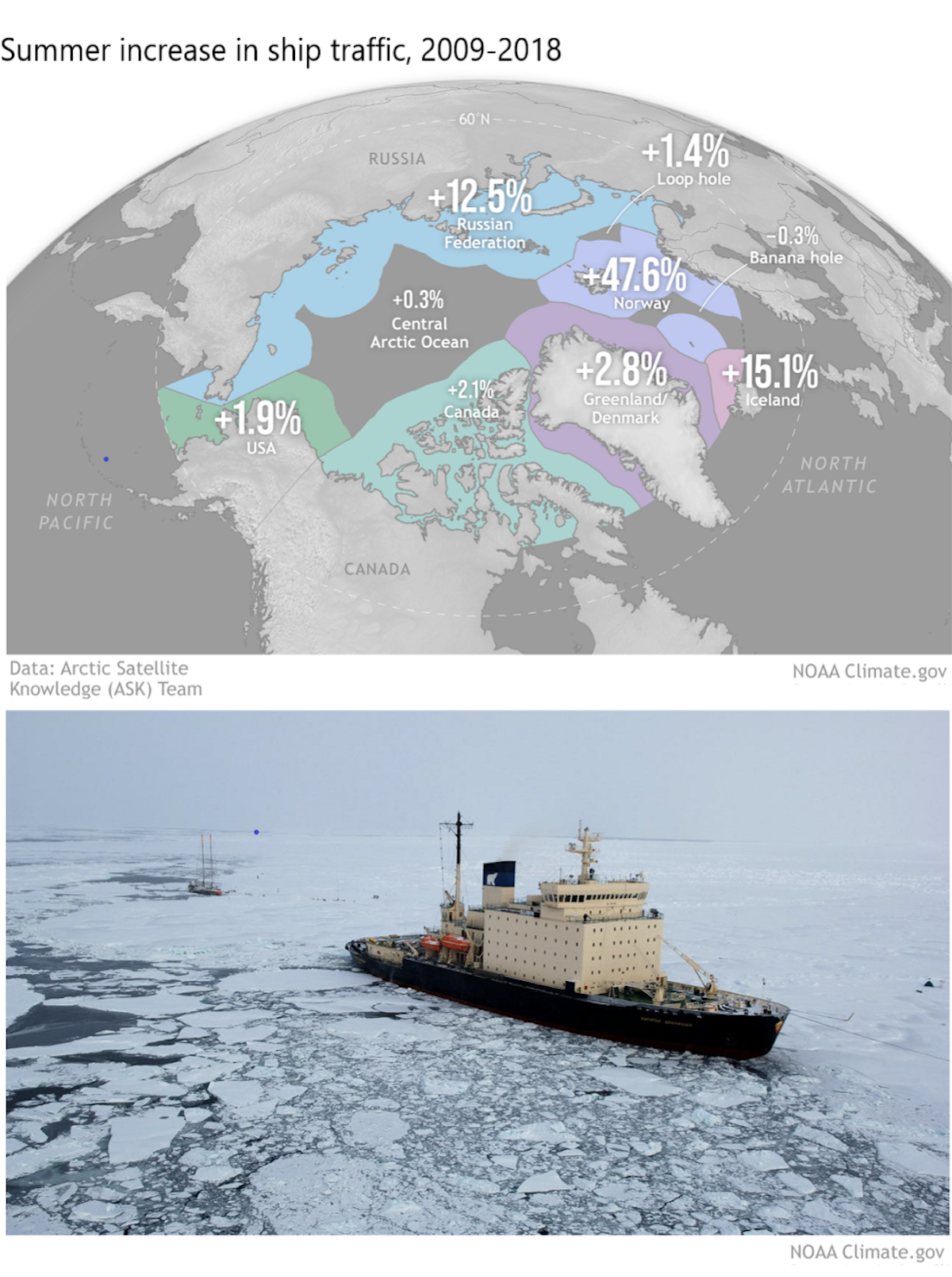

In the warming Arctic, this requires decision-makers to better anticipate the interplay between a changing climate and human activity. For example, satellite-based ship data since 2009 clearly show that maritime ship traffic has increased within all Arctic high seas and national exclusive economic zones as the region has warmed.

For these ecologically sensitive waters, this added ship traffic raises urgent concerns ranging from the future of Arctic trade routes to the introduction of even more human-caused stresses on Arctic peoples, ecosystems and the climate. These concerns are especially pronounced given uncertainties regarding the current geopolitical tensions between Russia and the other Arctic states over its war in Ukraine.

Rapid Arctic warming requires new forms of partnership and information sharing, including between scientists and Indigenous knowledge-holders. Cooperation and building resilience can help to reduce some risks, but global action to rein in greenhouse gas pollution is essential for the entire planet.

After reading this, I am thinking that whole communities will have to be voluntarily evacuated south to land that is still stable – at the moment. The changes taking place are too rapid and are also accelerating from what I have read. Sure you could have all sorts of sensors in and around those communities where they are at the moment to give warning of more severe changes but this would be only putting off the inevitable. We have been hearing about tipping points for decades but for these communities, it sounds like they have already been tipped into it.

And hundreds of Private Jets full of self-important aristocrats burn kerosene, spewing CO2 high in the atmosphere, over the shorter routes over the Arctic, every day.

And what is that sound? Silence.

Oh My God………Oh My God…….The beavers are returning to the Arctic!

“The transformation of the rapidly warming Arctic is being accelerated by a wave of thousands of newcomers that are waddling and paddling northwards: beavers.

Scientists who sought to map the spread of beavers in Alaska were astounded to find that the creatures have pushed far north into previously inhospitable territory and are now set to sweep into the furthest northern extremities as the Arctic tundra continues to heat up due to the climate crisis……”

“Snow Extent in the Northern Hemisphere now Among the Highest in 56 years Increases the Likelihood of Cold Early Winter Forecast both in North America and Europe.” This report directly contradicts the claims in this post.

https://www.severe-weather.eu/global-weather/snow-extent-northern-hemisphere-highest-56-years-winter-cold-rrc/

No it does not. For one thing, this article is about the Arctic. Your link is about the entire northern hemisphere. Second, The idea that Arctic ice is declining is not exclusive from greater snow extent throughout the northern hemisphere. As the above article states, less sea ice leads to more exposed ocean surface subject to evaporation leads to more precipitation. Below, John Steinbach succinctly describes why more of this increased precipitation will fall as snow as opposed to rain.

Pat Dooley claims that impending cold weather in Europe & North America contradicts the report about Arctic warming. To the contrary. The colder weather in the upper mid-latitudes has to do with the decreasing temperature differential between the Arctic and the upper mid-latitudes, thus slowing the jet stream & permitting the Polar Vortex, which keeps cold air “bottled up” in the Arctic, to slow down and wobble, thus permitting Arctic air to pour south.

Everything is fine and well… until it stops being fine and well. The arctic is not isolated from the rest of the Northern hemisphere and these changes will have unexpected effects in subarctic and temperate regions below. Atmospheric and oceanic changes. Ice melting has not only an effect on oceanic water level. Another effect will be reduced reflection of sun energy by the ice pack during Northern summer. More energy absorbed by land and water, changes in sea streams, changes in the atmosphere some of these as described by John Steinbach above. Everything is fine and well.

I don’t want to disagree with the general thrust of the piece here, but I wasn’t surprised to see the 1979 cut-off in the sea ice plot there. This is very misleading in presentation – back in the 1990 IPCC report they’d backdated Satelite imagery to the early 70s from US Navy sats – this clearly showed 1979 to be a peak year for sea ice. I’d use a rolling average on the graph they included too.

I know this is and old post now, but FWIW I was right regarding the Sea Ice chart. You can see the full IPCC 1990 report at the below link – check out Figure 7.20 on page 225 which shows artic sea-ice levels at their lowest around 1973, peaking at 1973. No idea why they’ve latterly chopped the earlier data which they’d take the time to digitise from US Navy Satelites.

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ipcc_far_wg_I_full_report.pdf

There is a known process in Earth safety mechanism that has repeatedly occurred with Dansgaard–Oeschger cycle events where ice melt causes rapid cooling. There are many reasons for this in the geophysics papers.

Some light reading that touches on current record cold

https://electroverse.co/record-cold-caribbeans-cold-novs-sa-victoria-coldest-summer-temp-uk-freeze-arctic-us/