Yves here. Rajiv Sethi has an interesting take on the super high representation of legacy admissions at elite colleges…that they are in the best position to game the system by virtue of resources and no doubt access to information.

I do think both the original assumption and Sethi’s positing of reverse causality can be true, and it may vary by school. For instance, Harvard after Larry Summers trashed the endowment with super stupid interest rate swaps bets (Harvard had to cancel all sort of things from expansion plans to hot breakfasts), Harvard became extremely mercenary in its admissions policy and was seen by many alums as way too willing to compromise academic standards to snag students (which often meant parents) who were likely to donate generously to the school.

By Rajiv Sethi, professor of economics, Barnard College at Columbia University. Originally published at Imperfect Information

There’s a new paper by Raj Chetty, David Demin, and John Friedman on Ivy-Plus admissions that has been getting a lot of attention.

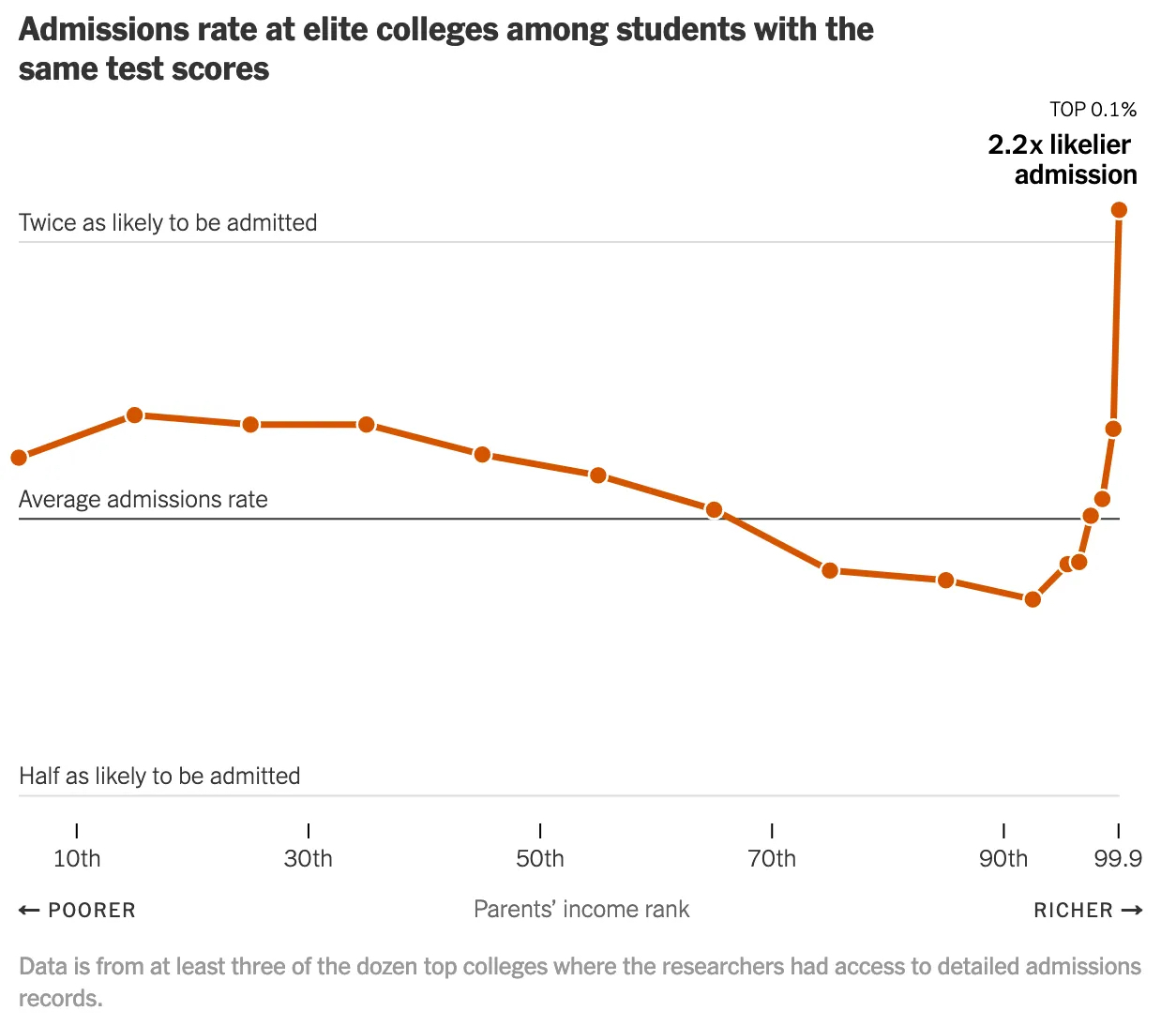

The authors had access to anonymized admissions data linked to tax records and standardized test scores. This allowed them to examine how the likelihood of admission varies with parental income at any given point of the score distribution. The following figure shows that conditional on scores, those at the very top of the income distribution secure admission at significantly higher rates (see here for the source of this figure, and here for the original version by the authors):

Undergraduate admissions at Ivy-Plus institutions is need-blind, and those making acceptance decisions do not have access to information on the parental incomes of applicants. So the pattern observed in the figure must arise from the use of selection criteria that value characteristics abundant among the very affluent. What are these criteria? The authors point to preferential admission for legacies, recruitment of athletes, and the value placed on certain non-academic credentials such as extracurriculars and leadership traits.

Some of the discussion prompted by the release of this paper appears to suggest that the admissions criteria adopted by these colleges are designed to result in the over-representation of students from the highest reaches of the income distribution. It certainly appears that recruitment for fencing or sailing advantages a very thin slice of the population. But I think this has the causality essentially backwards. If colleges were to start recruiting students proficient at ten-pin bowling or darts, you would quickly find these activities proliferating in private high schools and among the economic elite. Similarly, if colleges sought proficiency in Malyalam or Mende, it would not be difficult for those with ample resources to adjust.

Back in 1813, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams exchanged a series of letters on what would later come to be called metritocracy. Jefferson argued for a robust system of public education so that a “natural aristocacy” based on virtue and talents could be empowered, rather than an “artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth.” Adams was skeptical that one could so easily displace an entrenched elite:

Aristocracy, like Waterfowl, dives for Ages and then rises with brighter Plumage. It is a subtle Venom that diffuses itself unseen, over Oceans and Continents, and tryumphs over time… it is a Phoenix that rises again out of its own Ashes.

The findings in the paper appear to vindicate Adams.

How, then, might one move towards a fairer system? Abandoning legacy admissions and making recruited athletes go through the same selection process as other applicants (as MIT does) would certainly help. But an exclusive focus on academic credentials would create its own difficulties. Elite colleges don’t just want people who will ace their classes, they want future leaders in all manner of fields—scientists and engineers, founders of companies, celebrated authors, distinguished jurists, elected officials, civil rights pioneers, and so on. Academic records are too flat a criterion to identify potential across so broad a range of human endeavor. Furthermore, even academic credentials are resource dependent, and their proper interpretation must take this into account.

Recent work by Sandra Black, Jeffrey Denning, and Jesse Rothstein has examined the effects of the Texas ten percent policy, which guarantees admission to any state university to applicants graduating in the top decile of their high school class. The authors find that the gains to those who would not otherwise have been admitted are substantial, while the losses to those dispaced by the policy are negligible. The implication is that there may be value to considering both absolute and relative performance as criteria for admission, in a manner that is difficult (though not impossible) to game.

Another possibility is the use of lotteries. Elite institutions get many more exceptionally well-qualified applicants than they could possibly accommodate, and at some point admissions officers are surely left wondering whether they should just toss a coin. Literally doing so may not be such a bad idea, and those rejected would take it much less personally. Robert Frank has pointed out that even if the role of chance in determining performance is small on the whole, it looms extremely large for those at the very high end. Making the role of good fortune explicit would result in a more honest and transparent system.

For those interested in a closer look at issues related to meritocracy, I have a forthcoming paper with Rohini Somanathan that looks at the history of the concept, identifies conditions under which monotonic and group-blind selection criteria may not maximize performance, and surveys some relevant empirical evidence (including the Texas paper mentioned above, as well as related work by Zachary Bleemer and a fascinating study by Ursina Schaede and Ville Mankki that was discussed in an earlier post).

There is a type of value chain in admissions. Look at who is involved at each step of the way. Anyone who has worked in an office, for example, can tell you that paperwork can be shunted into this or that pile in the blink of an eye. Or moved up or down the pile when there is a wink and a nod, or casual comment. I’ve seen it happen, and many of you may have, as well.

Similar notions for digital workflow, although in theory there would be some auditing mechanism for either approach.

TL;DR – gatekeepers abound

We could just adopt the German system of tracking students and running college admission at the national level.

My wife came up through this system and my understanding is once you get to the University admission level, Admission is ultimately decided by your grades and performance on national tests. Grades are scaled for each state in Germany based on their academic rigor.

The results of this are never final, and if you want to go on university but don’t make it upon high school graduation there’s a wait list and point system that allows everyone the opportunity eventually if they desire.

Socially there could be some huge benefits in this because education reforms might be meaningful if high school seniors at elite suburban schools get penalized by the poor quality of education at adjacent urban schools in their state.

Allowing any cut-outs besides the purely quantitative academic evaluation is just a cut-out for the wealthy to game the system. The idea that there isn’t a broad enough sample of individuals “academic performance is too flat…” to give us writers, corporate founders, and sandwich artists from these elite institutions is BS and just another cut-out for the wealthy to get little Aiden and Jayden into Yale. If you’re worried about too many Asians in the Humanities, just base admission in those fields on verbal SATs and grades. No Math SAT needed if you are not going to take physics or calculus. Really surprised no one has reached for this solution by now.

This system would be more transparent and only institutions that want federal money/status need follow it. But the fact that this would be a step in the direction of meritocracy and class mobility is exactly why it will never happen.

In Ireland, admissions for school graduates are almost entirely dependent on their performance in the final exams (medicine is allowed some variations). Its a brutal system, but also extremely fair and even the most expensive schools have found it extremely difficult to game the system, no matter how hard they try.

This is, of course nonsense – there is no evidence whatever that these criteria can be identified among teenagers in a fair and transparent manner outside of academic records. This is how the upper classes fix admissions to favour rich kids.

I think you hit the nail on the head about allowing any cutouts besides purely quantitative academic performance. And I think this piece hit on the reason the system is not setup that way without really fully thinking about those repercussions. From the article, one of the stated objectives of universities is “they want future leaders in all manner of fields”. If that’s the case, setting up a system that can be gamed is exactly what universities should do. That is, afterall, what occurs in the corporate world–those who become leaders are the ones most able to game the system.

The question we as a society should ask is if we want to subsidize universities to this end. If you want federal funds, maybe its best if you focus on education rather than leadership

The other issue is that obviously the German system integrates college with high school with pre-k. The way our system breaks those up in the US is just another opportunity for grift and gaming the system. It’s a feature not a bug.

Yes. The focus must be on actual education, one that exercises ‘virtue and talents’, not simply being at the head of the pack.

And “Leadership” is slippery anyway, because you aren’t leading if no one trusts you enough to follow. In fields where real success requires understanding and expertise that is both broad and deep, this means convincing talented individuals to work together with commitment, and the best leaders may exert direction only to resolve competing ideas that keep the group co-operative and focused on common goals, and avoid bullying, grasping for recognition, deceit, and other ‘gaming’.

In China, cram schools sometimes display slogans to the effect that “Testing is where you can compete on equal terms with the children of the rich!”

For centuries, Imperial China assigned government posts based on national standardized anonymous test results, while in the West, the best way to get a government job was to be the cousin of some Grand Duke’s catamite.

You greatly understate the importance of nepotism in China and Sinosphereic cultures and greatly overstate its importance in historical Western cultures. The content, administration and outcomes of Chinese imperial state exams could be quite political depending on the era, and racial quotas were certainly a thing.

In the Roman Empire heredity was the rule, but so was strategic adoption, thus mitigating the risks that a poor genetic heir would not destroy a key institution. While the Germanic warlord forbears of much of medieval Western nobility deplored adoption and valued direct blood inheritance, institutional actors were well-aware of the drawbacks, and this is one reason why Western rulers traditionally did not hold absolute power, so that an auxiliary institution could compensate for a weaker one. Not even in France under the “royal absolutists” Louis XVI and Louis XV was executive power even remotely absolute and arbitrary.

The British military employed an elaborate and very standard examination process already in the 18th century.

“Elite institutions get many more exceptionally well-qualified candidates than they could possibly accommodate..” Don’t know if this is still true, but perhaps twenty years ago, I heard the head of Harvard’s admissions office discuss a study they did. They looked at the 2000 students they had admitted, then looked to see how the class would have looked if they had instead admitted the next 2000. There was no qualitative difference. Then they compared the next 2000 – still no qualitative difference. Only when they got to the fourth 2000 was there a difference. Perhaps the admissions officers are desperate for some way to choose between equally qualified applicants.

A good education is not a commodity and it should not be rationed. It’s more akin to oxygen or water or sunshine. Its most remarkable feature is that it grows from its own foundation.

“Elite colleges don’t just want people who will ace their classes, they want future leaders in all manner of fields”

That perfectly expresses the fact that these institutions have absolutely nothing to do with *education*. Their whole “meritocratic” purpose is to train up the ruling class’s most effective cadres to administer the capitalist system of economic exploitation, social privilege, and environmental depredation. Of course, such types are best found within the ruling class itself, along with cooptable climbers and “strivers” from among the plebes. Nothing of value would be lost were they all simply to be abolished–but a genuine public system for real education would have a better chance to be developed.

New York City ran a pretty good public university system. The colleges were never considered to be feeding schools for the ruling class. They were good enough so that besides graduating school teachers and accountants, 15 Nobel Prize winners got their degrees from the City University. Tuition was free and admissions was based solely on test scores and grades. As a side note, very poor kids could study esoteric subjects like art history and philosophy.

If Dubya could get into Yale then they will clearly let anyone in. Trump’s son in law (Harvard?) might be another example.

Probably none of this would matter so much if Ivy admission hadn’t become such a coveted ticket into the ruling class. Education like other PMC institutions is gaining too big a footprint.

I think Hunter Biden went to Yale. You could not make this stuff up!!

Just recently I read from Carolyn Eisenberg’s Drawing the line, how two months after Pearl Harbor Roosevelt tasked State Department to plan what kind of post-war world USA wanted. State Department, unfortunately, was staffed “by upper-class, Ivy League gentlemen of limited practical training and experience“, so they asked the Council of Foreign Relations to do all that difficult stuff for them.

So, we learn from this that way back then you were supposed figure out the end game when you went to war, and that the useless “meritocrats” knew they were useless and asked from the people who knew a thing or two.

Of course, CFR was a bunch of religious free-marketers who wanted to betray Soviet Union and split Europe to “contain” her, which was to have some consequences we’re still dealing with.

In the UK. “Oxbridge” on your CV guarantees everything cushy with no downside, no matter the scale of the debacle you subsequently engender.

Ps. The inculcation from birth that a wrong answer is more life threatening than a risky answer that triggers a bonanza has resulted in a ruling class of high achieving test takers whose risk aversion is off the charts.

Instances of this are too countless to mentionl.

I’m an American living in the Deep South, so I don’t run into many Oxbridge graduates. However, the few I’ve met didn’t seem to have unusually good jobs. They might’ve gotten into the same slots via our state universities. I think Peter Turchin, with his ‘overproduction of elites’ theory, is onto something.

In Europe the meritocratic idea has become dominant via the infamous “Bologna” process.

But what does it bring about?

Smarter students? Better professionals? more knowledgable, more reliant individuals?

nonono.

The underlying issue is lack of passion.

Kids dont get the chance to develope passion and an understandig for the sense of matters.

Especially not if they are bound to follow the Classic paths of academic success since developing passion and receiving good grades exclude each other in this system.

And that itself is a misundertanding inherent to capitalist thinking.

But what does it bring about?

What I have observed so far:

1) Winding down small faculties, courses, and curricula, no matter how excellent they were, because Bologna requires a minimum number of students for accreditation.

2) Students optimizing their cursus with respect to points and credits, not learning.

3) A proliferation of ever-changing Masters in esoteric specializations or combinations of fields, making it even more complicated to figure out what the final diploma is about and what it is worth.

I have no genuine observations of my own since my time ended long before Bologna started and I was at art school anyway, where things always were different (fortunately so.)

So I only know from reading articles by people with tenure. They say what you say.

What is so disturbing is to understand how the systems works on the inside.

How was it possible to push Bologna through despite some considerable resistance on some levels of administration, albeit not all of them.

What we have now, youth incapable of understanding the complex nature of the Ukraine War, the importance and nature of WMDs politics etc. is to major parts an effect of Bologna.

The same is true for the identity quagmire (although it´s being exaggerated by the media for self-serving purposes.)

p.s. in the splatter Sci-Fi movie “Starship Troopers” (1997) the bugs counter the humans by sucking their brains out.

Thats what the elites have accomplished. They are finding ways to weaken the “people” by destroying their knowledge base.

Thats one reason why labour unions were hated in the early 20th century. Workers were self-educating.

There is a matrix to be analyzed from there to here.

My point (3) above might be linked to the rise in popularity of University rankings in the past couple of decades. Since it has become so difficult to make sense ouf of the growing thicket of Masters’ titles, it is easier to fall back on “The Master that person got in whatever field was delivered by an institution that is ranked on the top X%, so it must be something solid”.

Point (1) is actually quite public — initially when Bologna was put in force, the consequences were obvious, with Universities suddenly losing courses and even entire curricula (and as a consequence, professors and research teams). This was presented and discussed in the press, although Bologna was never put in question — proposed solutions were typically to merge or to transfer faculties from/between several Universities. Such closures happen from time to time, whenever the number of students in a specific branch falls below the Bologna threshold, and usually result in a few articles in the press.