Today we will give a high-level look at part one of Jonathon Sine’s The Rise and Fall of LGFVs. Sine’s article is very detailed, yet written with an eye to holding reader interest. Here Sine succeeds by going through the history of how these vehicles, which have are the mechanism for blowing China’s real estate bubble so big and creating serious economic/investment distortions.

I hope to limit how much I recap the evolution of the LGFVs and instead focus on how they’ve created tremendous leverage in these structures, along with (in many cases) so much complexity that they would be difficult to unwind even if someone were so bold as to attempt that.

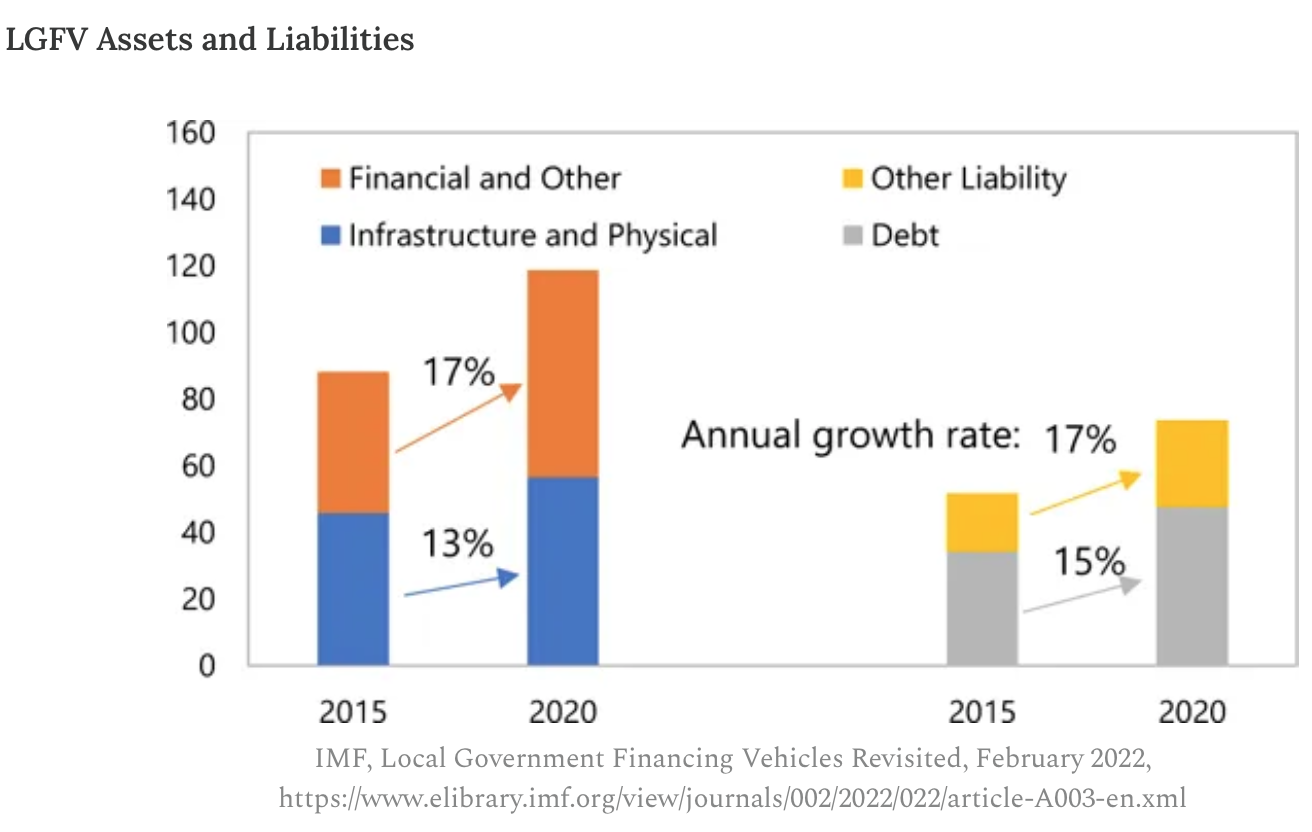

What leaps out of Sine’s account are three major destructive features of the Global Financial Crisis: Hyman Minsky-esque Ponzi finance, leverage on leverage, and complexity. This resemblance becomes more disconcerting in light of the scale of the LGFVs: their total assets are roughly 120% of Chinese GDP and their liabilities, 75%.

As disconcerting is that they’ve been growing at a markedly higher rate than overall economic growth, even at their current large size. LGFVs will eat the economy! Wellie not but they sure are trying:

Let us return to the first big alarm bell, the fact that the LGFVs are nearly all an exercise in Ponzi financing. For those of you who missed the discussion during the financial crisis years, here is a summary of economist Hyman Minsky’s theory and terminology, from a 2007 post:

Hyman Minsky, an economist who studied speculative behavior in the wake of the 1929 crash, observed that creditors become more lax about lending standards during times of stability. He divided borrowers into three types: the upstanding sort that can pay principal and interest; speculative borrowers (or “units”), who can pay interest but have to keep rolling the principal into new loans; and “Ponzi units” which can’t even cover the interest, but keep things going by selling assets and/or borrowing more and using the proceeds to pay the initial lender. Minsky’s comment:

Over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move to a financial structure in which there is a large weight of units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance.

What happens? As growth continues, central banks become more concerned about inflation and start to tighten monetary policy,

….speculative units will become Ponzi units and the net worth of previously Ponzi units will quickly evaporate. Consequently units with cash flow shortfalls will be forced to try to make positions by selling out positions. That is likely to lead to a collapse of asset values.

Again, keep in mind the key feature of Ponzi finance being unable to pay interest in full, and having to rely on asset sales or yet more borrowing to meet obligation. From Sine:

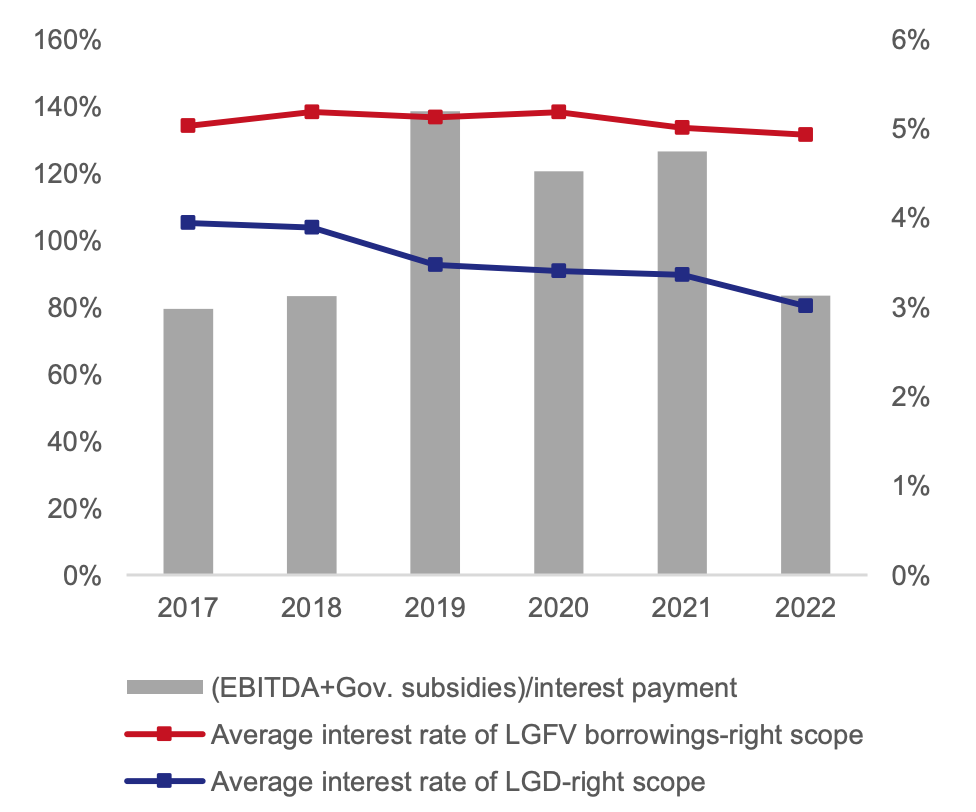

LGFV’s financial situation is, to put it frankly, very bad. In aggregate, earnings (before interest, taxes, and depreciation, i.e., EBITDA) do not cover even their interest payments. Including government subsidies only occasionally pushes the interest coverage ratio above one. Moreover, the average borrowing cost for LGFVs, 5% or so, far outpaces their 1% return on assets, posing obvious sustainability problems.

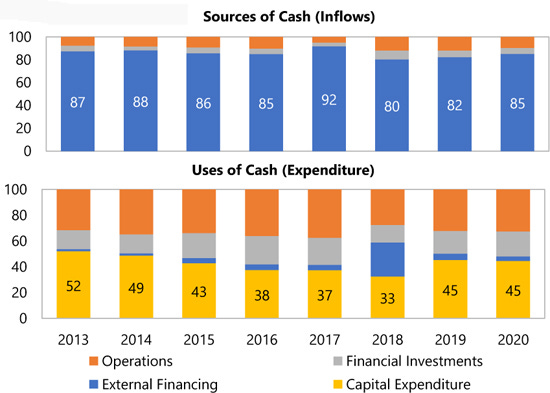

Cash flows paint an equally troubling portrait. Every year 80 to 90 percent of LGFV spending is funded by new debt. On the whole, LGFVs operating inflows do not come close to covering operating expenses. New debt is routinely added simply to make up the gap and sustain current operations.

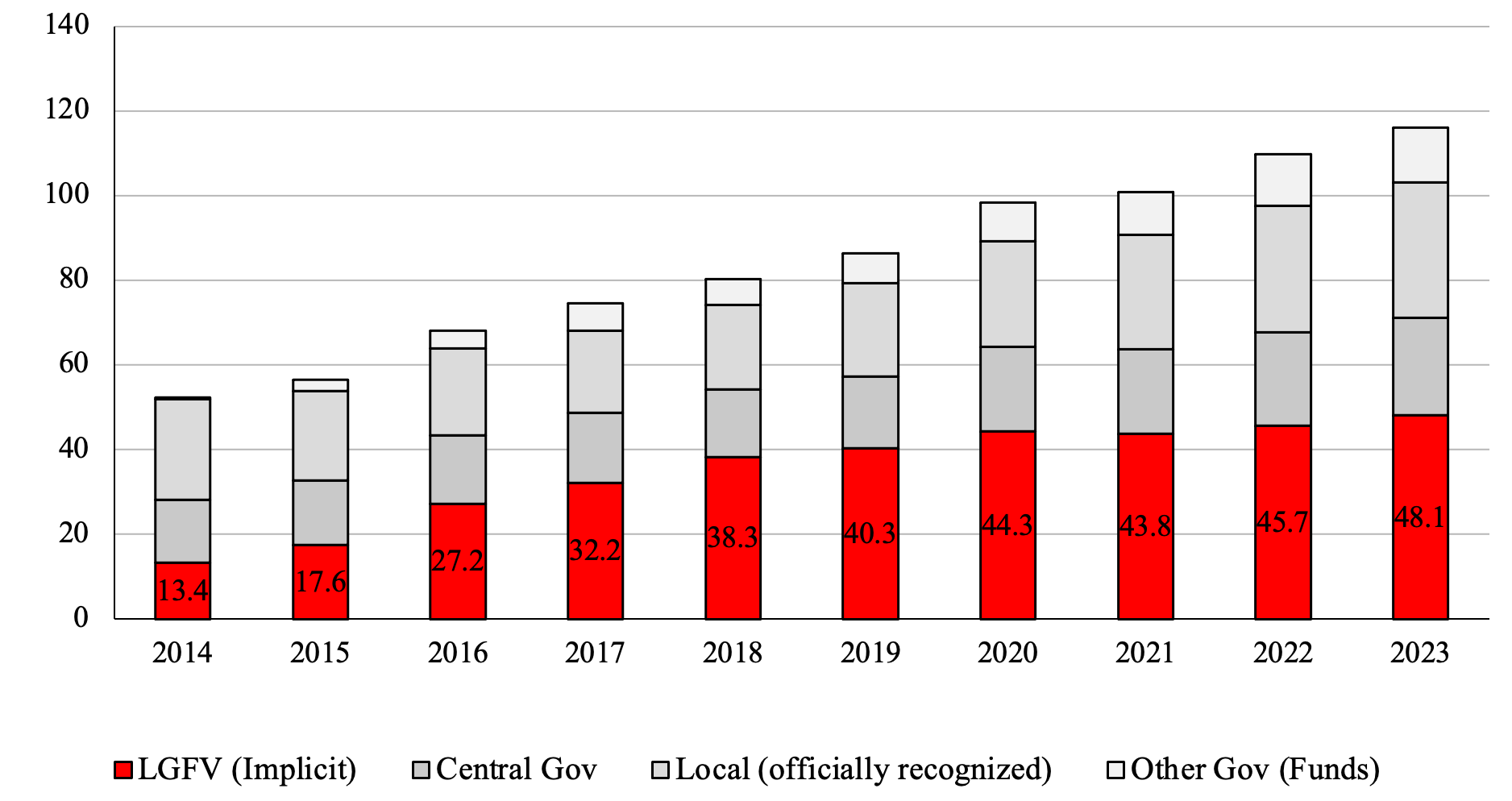

As is predictable from the above financials, the stock of interest-bearing LGFV debt has just about unceasingly expanded.4 According to statistics from the IMF, LGFV’s interest-bearing debt has grown from 13% of GDP, or RMB 8.7 trillion, in 2014 to 48% of GDP, or RMB 60.4 trillion, in 2023.

LGFV interest-bearing debt is even larger than the IMF data above suggests. An unavoidable limitation of assessing LGFVs via bottom up data, as all of the above sources do, is that it only captures the 2-3,000 LGFVs that have issued bonds and published associated financials. Another 9-10,000 smaller LGFVs have never accessed the bond market and are therefore simply missing from the data.6 A simple way of trying to estimate the rest of the interest-bearing LGFV debt is to assume LGFVs follow a Pareto distribution.7 Doing so suggests IMF estimates probably understate debt by 25%. A more reasonable, if still likely conservative, estimate of interest bearing LGFV debt is probably 60% of GDP, or RMB 75 trillion, in 2023.

We’ll skip over the first part of Sine’s in-depth history of how the LGTVs came to be. A short and highly simplified version is that Chinese government was exceptionally decentralized, which in the post-Mao, pro-market era became a problem as the role of state-owned enterprises and tax revenues shrank. Beijing, to restore its power, implemented a system in the early 1990s very much akin to Richard Nixon’s revenue sharing, but more so: the central government collected tax receipts and distributed them to local entities to spend, with the funds sometimes going through complex channels. Goods and services taxes account for about 60% of the total, with only about 6.5% from income taxes.

So the local governments got around the central government revenue constraints by creating off-budget liabilities. And the LGTV was devised by experts at the China Development Bank.

Skipping over the mechanisms the local governments used, the funding came from banks….which increasingly were newly-created, locally controlled banks. Not hard to see where this is going…

To fast forward to the global financial crisis, recall that China engaged in very large scale stimulus while the rest of the world underspent. As Sine notes:

When the center boldly announced its RMB 4 trillion stimulus plan to ward off recession, it did not intend to fund the stimulus directly but instead turned to local governments, now replete with bank licenses and financing vehicle. To this day we don’t know exactly how much China actually spent on its stimulus, though its clear the vast majority came off-budget via LGFVs….

Predictably, Beijing quickly lost what little control it had of the LGFV expansion process. Not only was the credit expansion much greater than Beijing intended, but LGFVs institutional role expanded and embedded deeper into the sinews of China’s economy.

The central government became unhappy with how the LGFVs had gotten too big for their britches, first running intrusive audits, then creating lists of shaky-looking LGFVs and pressing banks not to lend to them.

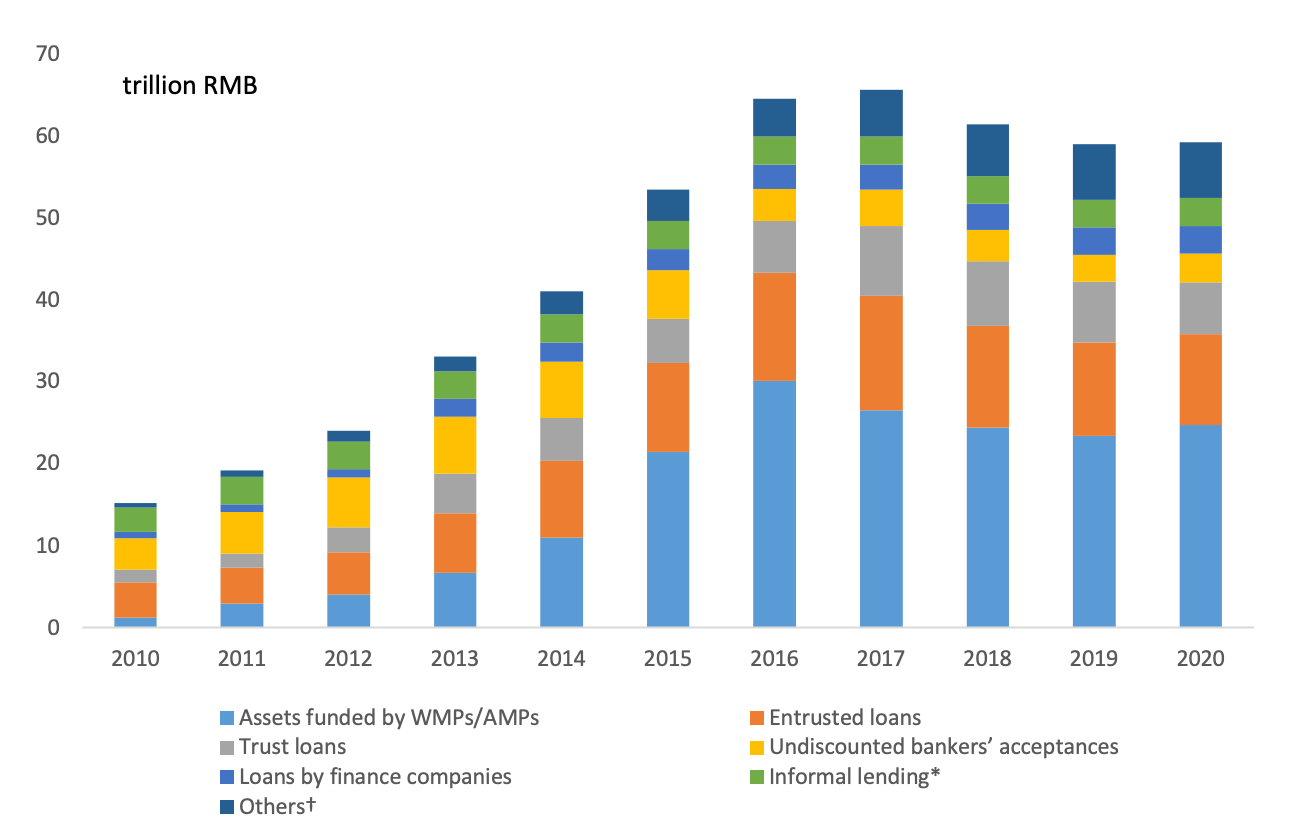

So the LGFVs found new money sources: municipal corporate bonds, which by 2018 had become 1/3 of all corporate bonds, and shadow banking.

Another echo of the crisis comes in the half-pregnant status of the corporate municipal bonds. Again from Sine:

…..most “bond buyers preferred LGFV bonds because they offered higher yields than corporate debt, but were considered government guaranteed, even though they funded projects that typically had no capacity to repay the debt.”

Remember how Fannie and Freddie debt were considered to be government guaranteed, until Freddie looking green at the gills forced the recognition that they weren’t, legally? And then Treasury put both Fannie and Freddie into conservatorship to contain market upset?

Sine points out that both the corporate municipal bonds and the shadow banking, which consists mainly of so-called wealth management products, actually do wind up back at banks, in ways that circumvent regulations:

Wealth Management Products (WMPs), or special funds set up to skirt regulations on deposit rates, are the most important shadow banking product. WMPs invested heavily in municipal corporate bonds. Chen and He et al calculate that 62% of all MCB proceeds came from WMPs. And it was banks that created those WMPs, of course with money that ultimately belongs to household depositors/lenders.

There are additional flavors of LGFV-financing regulatory arbitrage, such as entrusted loans and trust companies.

Let us now turn to a second concern, leverage on leverage. That was what set up the Roaring Twenties boom to end in the Great Crash (with trusts of trusts of trusts and CDO-like structure) and the Financial Crisis (in which, as we showed in ECONNED, CDOs created spectacular leverage). Sine provides an example:

Zunyi is relatively unremarkable, a city of middling population and economic development, firmly in the 3rd tier of China’s unofficial city ranking system. One recent development, however, has once again brought attention to the city: the increasingly urgent Party-state effort to deal with LGFV debt. Zunyi Road and Bridge Construction (遵义道桥建设) is the star of the show. A snapshot of Zunyi’s corporate structure offers hints at some of the poblems.61

Zunyi Road and Bridge, like most LGFVs, is fully-owned by the local, in this case city-level, State Asset Supervision and Administrative Commission (SASAC).62 Established in 1993 and with registered capital of RMB3.6 billion, it is the second largest of of Zunyi SASAC’s 40+ holdings, many of which also appear to be LGFVs. Zunyi Road and Bridge is itself a holding company with at least 10 companies under its umbrella. Many of these firms are also LGFVs. Its largest holdings include: Zunyi Daoqiao Agricultural Expo Park Co., Ltd., Zunyi Daoqiao Hotel Management Co., Ltd., Zunyi New District Construction Investment Group Co., Ltd., and Zheng’an County Urban and Rural Construction Investment Co., Ltd.

Zunyi Road and Bridge Holdings

Zunyi Road and Bridge holding structure, 遵义道桥建设(集团)有限公司, 股权穿透图, via 爱企查 https://aiqicha.baidu.com/company_detail_69261055076241

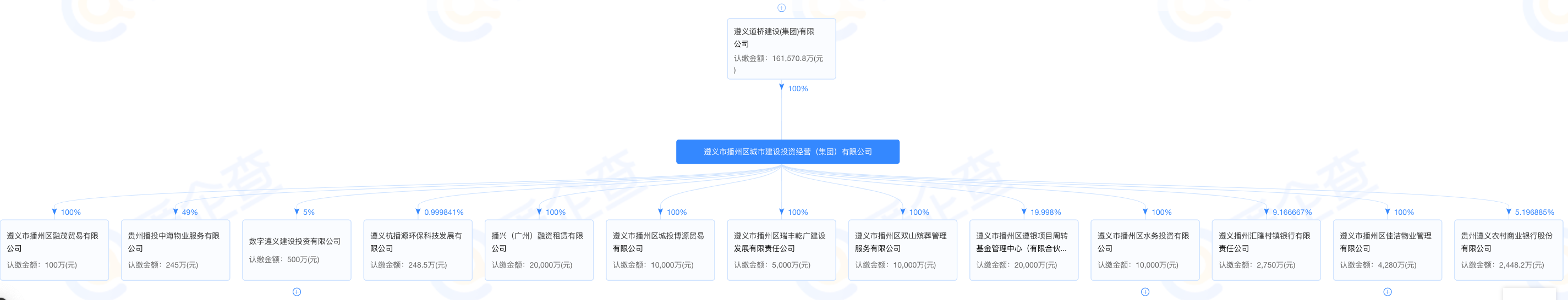

Road and Bridge’s subsidiaries also have subsidiaries. Take for example, its largest subsidiary: Zunyi City Baozhou District Urban Construction and Investment (遵义市播州区城市建设投资经营), with registered capital of RMB 1.6 billion. Baozhou Urban Construction itself fully-owns a diverse array of 10+ businesses, ranging from a funeral service company, to a financial leasing company seemingly focused on industrial equipment, to a water services management company, as well as a 49% stake in a property management company and a 5% stake in another diversified LGFV holding company.Holdings of Road and Bridge Largest Subsidiary, Baozhou Urban Construction

Zunyi City Baozhou District Urban Construction Investment Management (Group) Co. (遵义市播州区城市建设投资经营(集团)有限公司), 股权穿透图, via 爱企查 https://aiqicha.baidu.com/company_detail_62311309937102

The financing practices to go along with such a web of holdings have been similarly convoluted. One company may acquire loans or go to the bond market only to on-lend to its affiliated entities. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of LGFVs like Zunyi Road and Bridge and like the one in Dashan County mentioned earlier. These conglomerate LGFVs undertake what economist David Daokui Li describes as a “nested layering approach” to leverage. Companies at one level borrow funds, use that borrowed capital to secure additional loans at the next subsidiary level, and amplify debt layer by layer. All the while moving into more and more lines of business.

Needless to say, multi-entity enterprises, all lashed together with cross-ownership and debt, are well-nigh impossible to analyze accurately, let alone unwind. AIG had a similar bird’s nest of exposures in its property and casualty subsidiaries, with cross-ownership, cross-guarantees, and different fiscal year end dates too. Recall that when AIG was effectively nationalized, the plan was to sell its various entities. That never happened. The cross-exposures were a big reason why.

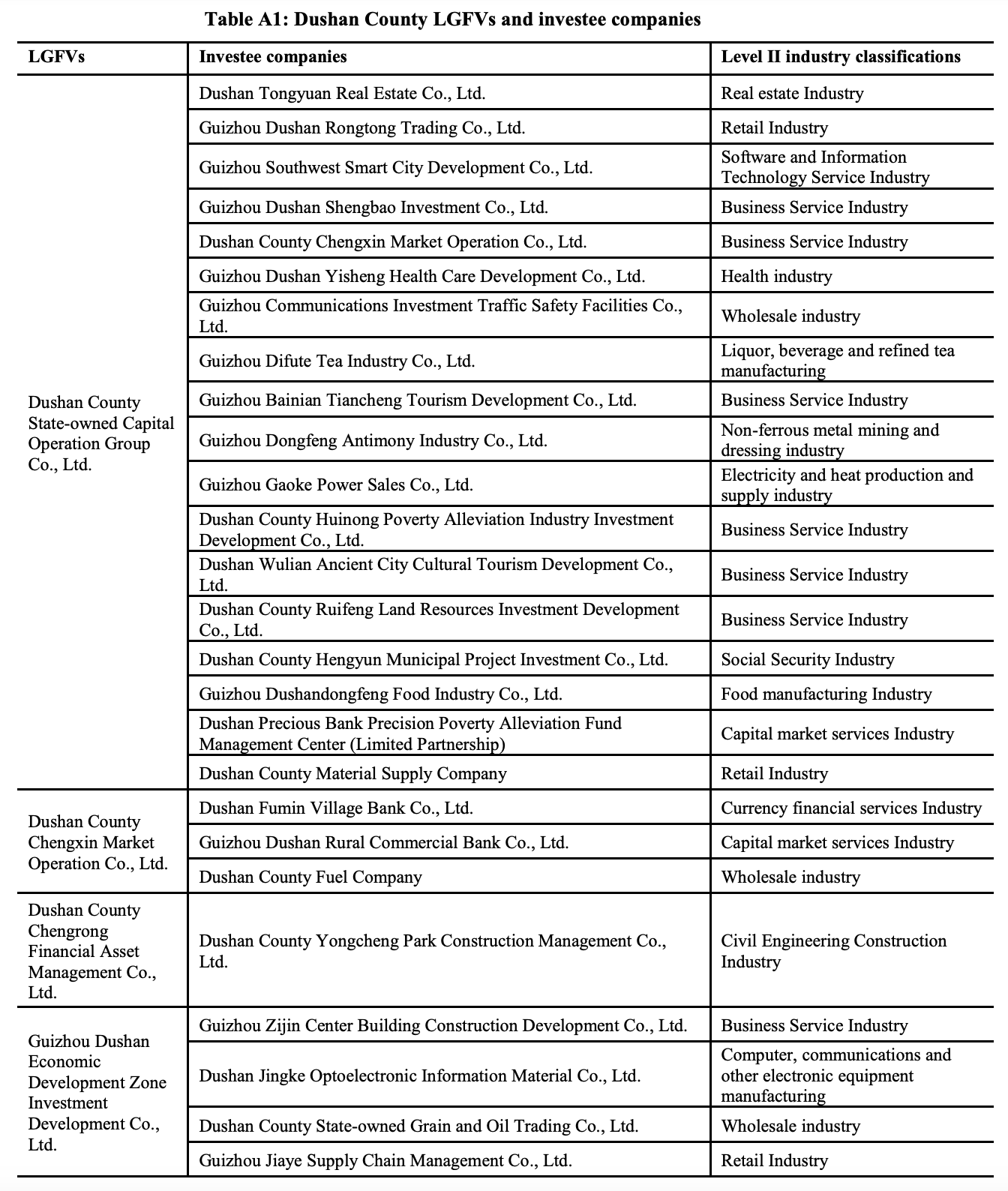

To keep the post to a manageable length, and not over-hoist from Sine, we are giving comparatively short shrift to the third worrisome sign, complexity. You can easily see the organizational and financial complexity of the Zunyi Road and Bridge entities. We have skipped over the complexity of the businesses that the LGFVs get into. An extract from a longer discussion:

As they expanded, LGFVs moved out well beyond their initial infrastructural and land development remit. One analogy is that LGFVs have become akin to twelve thousand little Huarongs. Huarong, the country’s largest asset management company, was established just a year after the first LGFV in 1999. Colloquially referred to as a “bad bank” because it was set up to take non-performing loans off the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s balance sheet. Initially an asset recovery firm, Huarong metastasized into a massive conglomerate with dozens of subsidiaries involved as many different industries. The crazed expansion got so crazed under former Chairman Lai Xiaomin that the CPC decided to execute him.

See this example:

Now this entire mess would seem primed for a very bad end. Yet many commentators have been predicting bad ends for China’s real estate bubble and its myriad financing mechanisms for some time, and no crisis has occurred.

However, another outcome from a big debt overhang is zombification: too much money going to refinancing what would otherwise be bad debt, at the expense of better uses.

Herbert Stein famously said, “That which can’t continue, won’t.” But he was silent on when “won’t” might come to pass.

I guess the question I would like to ask the commentariat, is what happens in a Chinese type of economy when the won’t happens? The answer to this question, is way above my paygrade!

Or put it another way, some day it will unwind (likely not orderly) – what might that look like in the Chinese economy? I cannot imagine the central gov’t allowing a 1929 style crash with the resultant societal instability (the New Deal was supported by part of the oligarchy only because the threat of societal upset was real). And the massive western Quantitative Easing post-2008 has only kicked the can down the road while enormously polarizing (gini) society and increasing debt – the West’s “Won’t” is still pending. In the west, Greece gives a clue (massive suicide increase, emigration, homelessness, etc.), while the non-Greece west seems to seek salvation in military keynesianism.

It’s unlikely that the government will allow a total crash to occur, but crashes are what’s necessary to unwind this whole mess.

Maybe Evergrande was a sign of things to come because they allowed it to fail while mitigating the damage.

Overinvestment in real estate and debt in general are slowing down the Chinese economy, it’s just not a critical point yet. They seem to be aware of the issue, it’s just that there are no good solutions.

Beijing have tight control over the countries finances, so a western style crash is highly unlikely, bar some complete screw up. The key problem is the insane complexity of these vehicles means that any rational attempt to sort out the mess will take many years, even decades. The greatest economic danger in my opinion is a long term deflationary slump, something like Japan, albeit at an earlier stage of development. The big political danger for Beijing is youth unemployment, which is likely to be very high at the moment (they stopped issuing official figures), and is likely to get worse as things get even tighter at local level.

It seems now that Beijing is gambling on exports making up the slack. The problem is that the sheer size of China makes this almost impossible – nobody – especially China’s neighbours – want to see their industries devastated by a wave of Chinese exports just to bail out Beijings domestic problems.

The problem concerns who is GUARANTEEING the loans. I’m told that some banks have guaranteed payments on Evergrand’s borrowings and those of other companies. And some bondholders are foreign, complicating matters.

This could have been avoided by a land tax that would have collected the rising rental value of housing that has increased their prices. It is that hope for price increase that has led Chinese to save in the form of buying housing — forcing new homebuyers (for their sons, so that they can get married with the proper asset qualification).

The fact that many Chinese economists are trained in the US doesn’t help them understand this problem.

Would it be possible for the central bank in China to take over all the domestic borrowings and write them down as needed?

Similarly, would it be possible for them to eventually just write down the foreign bondholders under the pre-text of being blocked by sanctions or something?

Sorry if these are bad questions, just some wild speculation from me

I’ve always wondered about the practice of selling off loans, I’m thinking of student debt in the uk, sold at pennies on the face value.

The government books are purged, yet the victims are left on the hook, when they could have more easily extinguished them at the vulture rates.

But then, that might give the vibrant ,essential workers in the PE sector a big sad.

Jamie Galbraith talks up the land tax too. It would be great to hear you two debate this decades old solution.

Talking about the Galbraiths, John, in column for The Nation (i believe), once said that the only current Republican agenda was the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness.

“Talking about the Galbraiths…”

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html

September 13, 1970

The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits

By Milton Friedman – New York Times

When I hear businessmen speak eloquently about the “social responsibilities of business in a free-enterprise system,” I am reminded of the wonderful line about the Frenchman who discovered at the age of 70 that he had been speaking prose all his life. The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades…

https://wist.info/galbraith-john-kenneth/7463/

December 18, 1963

The modern conservative is not even especially modern. He is engaged, on the contrary, in one of man’s oldest, best financed, most applauded, and, on the whole, least successful exercises in moral philosophy. That is the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness.

— John Kenneth Galbraith

The aspect of this report I found most interesting is that so few of the LGFV enterprises are profitable.

Does that not strike you as rather peculiar?

Here’s the caption under the 2nd bar-graph above:

It’s not like the LGFVs are just investing in real estate, and that one pony is tired. The example of Dushan County LGFV’s subsidiaries (above, in article) is basically the entire local economy.

The trends imply that some sort of adjustment will eventually get made. These options come immediately to mind, maybe you can think of some others:

a. Weed out the non-performing (unprofitable) subsidiaries. The graphs above don’t give much insight into the stars .vs. turkeys ratio, so this might not work as a solution

b. Increase prices for goods sold, or decrease costs, in order to increase profitability. I don’t get the impression that Chinese producers can wring a lot more cost out of the equation. That leaves price rises. And you’d expect price-rises; the Chinese std of living is going to continue to rise, and that means more spending power at the household, which means higher wages … and higher prices. While household income goes up, you can tuck some corporate price rises under that carpet, as well. We saw a great deal of that during Covid.

c. Write off the debt. As Dr. Hudson has pointed out many times, China’s banks are (more or less) owned publicly, and the State can simply write off loans.

All of those techniques will likely get applied. What I find most interesting about this is “who is making the investment decisions?”. This seems to have been delegated substantially to the locales. Can anyone describe how those local holding companies come to be, what the social-order linkages are? Is it tribal (familial; some families have long-standing dominance in given regions). Is it political – e.g. party role, standing, etc?

This is significant because it tells a story about how well a major portion of Chinese investment is going to get made. How do you manage a national econ policy if … nobody’s following it?

But the Chinese _are_ following a policy, and it’s working.

Does anyone know how the national .vs. local policy-making dovetails, or relates, or collides?

But if you write off the debt there will be a massive backlash. As I understand it many ‘ordinary’ Chinese have invested their savings in these bonds. It’s not as if the shareholders are off shore multinationals.

Key point, and thanks for making it.

See my remarks below re: Resolution Trust Corp, and the U.S. S&L melt-down of the 1980s here in the U.S. The State protected the depositors of these banks, and wiped out the investors. A similar principle – to protect the vulnerable – could readily be applied by China.

It is my understanding – derived from Jonathan Sine’s remarks below, that there are sufficient assets to cover the liabilities, so the bond-holders could be “made whole”.

For a more “non-ideological” take on LGFVs (and the Chinese Economy in general) I would suggest Glenn Luk’s writing: https://www.readwriteinvest.com/p/lgfvs-the-path-forward . Readers will find investigations of good and bad outcomes, comparisons to Korean chaebol reform after the Asian Financial Crisis, and more. Sine actually links to Luk in this article but fails to mention the more balanced outlook in his analysis). Luk also recently did a deconstruction of the Rhodium Group’s “Overcapacity at the Gate” article regarding China’s industrial policy (interesting overlap because Sine did an internship at the Rhodium group and liberally uses their plots in his articles).

Regarding Sine’s post, there is certainly a lot of data but many of the original sources in his report do not describe their findings in such an alarming fashion. As an example, in the source of the second chart (not provided in this repost but in the original : https://www.arx.cfa/~/media/834250EAA848452D82966537A082CAE5.ashx ), the authors state: “Consequently, the magnitude of LGFV debt carries potential implications for the Chinese government’s financial landscape. However, despite the substantial scale of RMB60 trillion, we maintain a measured perspective and do not perceive an immediate cause for alarm.”

As an aside, despite Jonathon Sine’s introduction as “non-ideological” (based on testimony from a poster on this site), his Substack would seem to indicate otherwise. I will just quote a few excerpts.

“The Path to Hell is Paved With Righteousness” – ‘When Mao Zedong awoke in the early mornings, what—in his heart of hearts—did he think to himself? What did such a man, this notorious tyrant of history, really think of himself when he reflectively gazed into a mirror and into his own eyes? …. In Mao’s mind, ultimately manifested in propaganda, he was a hero, fighting to enact The Good™. In layman’s terms: he believed his own bullshit.’

“The Dialectic of Development” – … ‘The comparison between the other North-east Asian states is salient. Far from pioneering a ‘Chinese model’, I’d argue the PRC rather switched from a Stalinist developmental model imported almost whole-sale under Mao, to a Meiji Japanese development model imported almost whole-sale under Deng.’ (Further in this article Sine approvingly cites Frank Dikotter’s “The Tragedy Of Liberation”, a book with distinctly non-ideological blurbs by Anne Applebaum: ‘For anyone who wants to understand the current Beijing regime, this is essential background reading’ and The Guardian, ‘Essential reading for all who want to understand the darkness that lies at the heart of one of the world’s most important revolutions’.)

Interestingly, on Mr. Sine’s own webpage (https://jonathonsine.com/home) he at least has a few articles discussing EU and US economic developments but he has scrubbed these entirely on his Substack, presumably to cater to a “China watcher” audience.

Have a nice weekend all.

Thank you for peeling the onion further… in the past 2 days, Biden speaks with Xi (“candid discussion”) and “Yellen Faces Diplomatic Test in Urging China to Curb Green Energy Exports” (Original NYT seems 86’d). Why should China take such barbarians seriously?

I respect Yves’ non-barbarian analysis but she says “Yet many commentators have been predicting bad ends for China’s real estate bubble and its myriad financing mechanisms for some time, and no crisis has occurred”.

This time is different?

If you consider Glenn Luk ‘non-ideological’, then good luck on your investments. He is not an academic, he sells investment vehicles, and all his analyses should be seen in that light. He is certainly knowledgable about some aspects of China’s economy, but his wider economic/political knowledge (as per his widely mocked ‘insights’ into Japan), make him a questionable source of information. I read him occasionally for balance, but not as a source of unbiased information.

As for your comments on Dikotter – he is certainly on the ‘anti-Mao’ side of Chinese historians, hence his popularity with some neo-cons, but he has also written with great insight and sympathy with the plight of ordinary Chinese people during the period. If you’ve ever met and talked to older Chinese people who lived through that, you would probably have a dim view of Mao too (as, to a large extent, does most of the mainstream CCP these days). Equating a dim view of Mao with some sort of bias against the current Beijing government is very far off the mark.

I’ll just chime in to direct the original commentator to some of my earliest footnotes in the piece, copied below. For the record, I’d probably say I am “evidence-driven” rather than “non-ideological.” And so far as I’ve seen, Glenn is similarly oriented and I enjoy learning from his perspective. Overall, though, I think it’s fair to say my assessment the the evidence renders me more pessimistic than Glenn on this issue.

“9

If we analyze LGFVs strictly in a financial sense, we miss a major part of the picture. Namely, the divergence between economic and financial returns. Many LGFVs invest in infrastructure projects with positive economic externalities but low financial returns, precisely the kind of investments private investors would not be willing to make and wherein market failures, in the neo-classical bent, are admitted to exist. A narrow financial assessment of LGFVs would therefore fail to capture potential positive social and economic externalities.

In addition, the above data should not necessarily give cause for concern over an acute crisis. LGFVs have an abundance of real assets that could provide some amount of income. In addition, some of those assets could be liquidated to pay down some of the debt. With an asset to liability ratio of nearly two-to-one (i.e., 125% to 70%), there’s substantial buffer. And most important, not only is nearly all LGFV debt held internally but most of the lenders are also state-owned. Counter-party risk is minimal.

10

Intellectual Yet Idiot, coined by Nassim Taleb. “Typically, the IYI get the first order logic right, but not second-order (or higher) effects making him totally incompetent in complex domains.” Some of his other examples of IYIs in his chapter from Skin In The Game are themselves quite dumb, but the acronym is still great. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, “The Intellectual Yet Idiot,” Medium, 2016, https://medium.com/incerto/the-intellectual-yet-idiot-13211e2d0577.”

Thanks so much for coming here to comment.

Yes, sorry, ‘non-ideological’ was a badly chosen description by me – I simply meant (but phrased poorly), that you don’t seem to have fallen into the trap so many Chinese commentators have of jumping into a perceived pro or anti China camp. I’ve found it so frustrating in recent years how many people I used to read who are now no longer trustworthy as they feel the need to defend ‘their’ side, whatever the real world data.

I liked your article a lot as you articulated very clearly details which others either skirt around or deal with tangentially. Plenty of observers have had deep concerns about how local government funding works in reality on the ground in China, but finding definitive data is very difficult. It doesn’t help of course that so few economists have read their Minsky.

This point is crucial:

This is a key thing that makes China so different from the U.S. They are using money to achieve public economic objectives, not to make profits for key players (investors, for ex).

China has public control over the creation of money, and – key point here – they have a fairly well-directed policy about where the public’s money gets invested.

I repeat my question voiced earlier in the thread:

How does top-level state economic policy about where to invest get communicated down to the locales’ banking operations (the investment decision-makers)? How is coherence maintained, and if it’s occasionally not-maintained, what’s the corrective mechanism?

Last evening, it occurred to me that the distributed money-creation power of the LGFVs is similar in some respects to the savings and loan (S&L) story here in the U.S.

To wit: In the 1980s, S&Ls created a lot of money by making a _lot_ of real estate loans which had the predictable effect of creating real estate bubbles, which popped, and the lenders (the S&Ls) went bust. The S&L’s assets had to be auctioned off by the Federal Gov’t via the Resolution Trust Corporation.

Key point: the banks were allowed to go bust. That is what didn’t happen during the Great Financial Crisis.

It seems like some of these LGFVs may need to be “resolved” in like manner at some point. But per the quote above, that resolution may be a bit of a side-show, a minor consequence of a major bloom of capacity-building, learning, standard-of-living increment, etc. The “social good” part of the story.

I don’t think you get it. The funders of the LGTVs are increasingly households, directly through the purchase of wealth management products, and indirectly via being depositors of banks.

As I indicated in comments on my earlier post on Sine, the resolution of the early 2000s banking crisis fell squarely on households, via banks offering returns on savings enormously below inflation rates, as in the banks were rescued by reducing the value of the bank liability of deposits. That led Chinese to save even more to make up for this erosion, further distorting the economy.

The loans are someone else’s asset. There is no way to write them off without creating a deflationary loss of wealth.

And you are acting as if this over-investment in housing is productive when it isn’t. This is not infrastructure as in bridges and roads, but primarily residential real estate speculation. That is why Chinese officials were disapproving of it in 2015, that investments were going into asset inflation, see the quote early in this post.

Yves:

Your point 1: ” The funders of the LGTVs are increasingly households, directly through the purchase of wealth management products, and indirectly via being depositor of banks. “.

Tom: That household-level risk exposure was also true of S&Ls. The state guaranteed depositors up to $250K, if memory serves. The state backstopped the vulnerable (mostly).

Your point 2: “The loans are someone else’s asset. There is no way to write them off without creating a deflationary loss of wealth.”

Tom: J. Sine states above that the asset (the land, business, whatever the loan was for) … the asset to liability ratio is favorable enough to liquidate the asset (sell it off) to pay off the loan

And yes, there will be some deflationary loss of wealth, but that loss ought to be borne by bank management / owners. Clean their clock first, and if the vulnerable are still going to take a hit, use the State’s money-creating powers to make them whole (at least mostly). That’s what RTC did, correct?

One of the things I don’t (yet) get is why the politics and pain of bubble-popping (the deflation) would be different in China .vs. the U.S. The scale may be different, of course, and maybe that makes this case qualitatively different.

If the use of the S&L and RTC example seems to indicate that I favor over-investment in RE, I don’t. I favor investment in productive uses that actually solve our problems, whatever that might be in the moment.

The other point – and this may be the truly complicating factor, is the leverage on the loans. If there actually isn’t a favorable asset-to-loan ratio, there’s the basis for the deflationary cascade.

Is that potential deflationary cascade the issue you’re trying to get me to see?

It seems to me a Party controlled CBDC would be a uniquely powerful tool to pursue and equitable allocation of speculative losses.

I am sorry, but that is a handwave. And start with telling me what are “speculative losses”? We are talking about lenders, and as Sine pointed out, banks. Allocating losses to banks result in hits to capital and potentially insolvency and/or bank runs. Please tell me how a CBDC solves any of that.

Okay, I’ll grant my hand wavy-ness and my lack of expertise. CBDC is however a new, centralized technology of control being implemented by a highly centralized political party that, I think, knows it has a distributed financial system problem that could be resolved centrally through control of the currency.

I can’t now find the link you previously posted about the use of CBDC to pay Party officers in China and some who promptly fell from grace, IIRC in the military. So its already being used politically. I know that in the US our Central Bank doesn’t want to underwrite retail banking, what’s to prevent the Party in China from doing so? And if they do, like the FDIC backstopping $250K for retail banks in the US, could not CBDC be used to guarantee the liquidity of individuals? I know there would be mechanical and plumbing problems with implementing such an effort, but the motive seems to be there to try.

Yes, there is a thicket of cross connections and confusing interrelationships that make sorting problematic, but because the external debts can be discounted, the West is already trying to contain China so to hell with us, and internal ones can be backstopped for the vulnerable, that could contain bank runs, in turn making space and time for the sorting problem to provide definition to “speculative losses”. Its a nominally communist country that just provided the communist version of Beatification to Xi, I’m not discounting the unique challenges and complexities, but neither am I discounting a unique power relation between Xi, money and technology.

I do not get it, so please enlighten me. To begin with loans are created by banks on demand not based on the loanable funds model, so these loans are a liability of the bank backed by the wmp or deposit or mortgage….Why does letting the bank go under necessarily require to burn depositors or households if their savings (deposits / mortgages etc) are guaranteed by public money while large investors over a certain treshold would not be bailed out and that portion of debt is written off. Hope I am not totally off with this.

I’ve had the opposite experience. Met plenty of older and younger Chinese who adore Mao. Millions still flocking to his mausoleum and birthplace every year to pay tribute.

That which can’t continue, won’t.

Is a fundamentally accurate observation, but it doesn’t follow that that which must end, must end all at once (except in the case of asteroids), or end in its entirety (except in the case of… idk black holes).

I’ve never worked on or operated an economy before, but I’ve worked on and operated complex machinery that produced a foundational product for the US economy. The first thing I learned about maintenance we’ve all heard – if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. This is important because things can look broken, and be working fine, or well enough – I could share plenty of stories of all the things I fixed until they were good and broke. My partner assures me no one is interested.

The first thing I learned about operations was hammer down, run it til it breaks.

Perhaps my analogy is too “classical” in form to apply to a “modern” economy, but if an Idiot like me can’t see the sense in pulling levers wildly to try to “fix” a (possibly emergent) situation in the Chinese economy, I can’t imagine Comrade Xi and his Band of Merry Men would find much sense in it either.

I have to also believe that in a country where corporate malfeasance is met with the death penalty (Lai Xiaomin), the message has been signed sealed delivered – fix it, or get fixed.

This system is broken. The central government tried to curb the LGFVs in the early teens and failed. The real estate bubble is now deflating, and with 70-80% of household net worths tied up in that, this is a monster political problem for China. They have propped up the system every time it got wobbly, thus creating the Chinese version of the Greenspan put. But real estate prices are down, to the degree I’ve heard princeling children here in second-tier Thailand say their residential real estate holdings are underwater (this one from someone who hailed from Shanghai and got stuck here during Covid), and they expect they’ll come back eventually, The way they discuss “eventually” sure sounded like “not soon.”

Thank you for the response.

Glad I tuned in this morning, lots of good new words.

The machine I operated broke down, if not every shift, then at least every day, for nearly the entire time I was employed as an operator. Even in that condition, the mill (I did the math once, 2015 numbers here) produced materials worth about $90k per shift, per lathe, for a daily average of say $360k. Not too shabby for a bunch knuckle dragging rednecks!

About 6 months before they *ahem* separated my employment (their words), management decided to rip the band aid, and rebuild the constantly failing hardware, as well as install a new computer control system. The lathe I operated went offline for about two non-consecutive weeks, ie management installed new mechanical for about a week, then 6-8 weeks later installed new wiring and computer.

The mechanical stuff, easy peasy. Loosen bolts, remove, replace, plug and play. The wiring, even easier – electricians are way overpaid.

The brain. At the time of my “extreme prejudice event” (termination), some 4 months after the engineers had left, the machine I operated was still producing (as I recall) 10-20 loads less per shift than its pre-intervention performance, due to new bugs, glitches, and UI that forced the operators to basically learn how to operate again from zero.

I apologize for droning. If I may do some final weaving. Perhaps the gov’t can change the mechanicals and wiring of the economy, through legislation or decree (i’m not sure how that works exactly in modern China), with medium or low short term impact, but brain surgery on a living breathing patient doesn’t sound like it would do much to help.

To Mr. Hudson’s point about raising taxes on rents extracted from land and other activities, from April 4 – with full confidence that I have no idea what I’m talking about, that sounds like brain surgery. The patient may seek a second opinion, and Dr. Gov’t may face its own “extreme prejudice event.”

I’ll see your that which can’t continue, and raise you one inertia…

Whoops.

“Dr. Hudson.”

My bad, sorry Dr.