PlutoniumKun, who as readers may recall follows Chinese social media and also has a keen interest in development economics, sent a new article by Jonathon P. Sine, a first part in a two-part series on the rise and fall of local government financing vehicles, the shadow banks behind China’s housing bubble. PlutoniumKun describes Sine as “one of the very few western based Chinese commentators who tries to stay above the ideological fray.” PlutoniumKun also reports that this article is garnering very keen interest on Chinese Twitter. That piece is so meaty, and intended to be a reference work, that we will turn to it in a later post.

But before we turn to this deep dive into LGFVs, which as of 2020 had liabilities of roughly 75% of China’s GDP, let’s first turn to Sine’s 2021 must-read piece, Financialization: Is it Worse in the PRC? Readers who have gotten a big dose of Michael Hudson describing how Chinese leadership has steered clear of the Anglopshere traps of neolibearlism and financialization will tend instictively to reject this claim.

But what Sine presents, and many commentators fail to deliver, is data. Lots of it. From lots of angles. One you’ve read his piece in full, it is hard to dismiss his argument that China is pretty bloody financialized, and even more so on a relative basis than the US.

Skeptics might argue that if Sine is correct, why hasn’t the China-bashing media seized on his thesis? One possibility: depicting financialization, and in particular the level of US financialization, as bad is not something the Western business media is keen to promote. Even if the claims that China is cruising for a bruising include some financial metrics, like declining economic productivity of borrowing (how much incremental debt it now takes to generate a dollar more of GDP), debt levels, debt growth, real-estate related bankruptcies, the doubters tend to focus on the notion that China’s growth rate is flagging or overstated, and contend that that has knock-on effects, particularly making it difficult for China to deliver rising standards of living. They also point out the implications of China’s low birth rate.

And even though Hudson is a critic of financial capitalism, as opposed to industrial capitalism, he’s not alone in that view. None other than the IMF pointed out that financialization, once it passed a not-very-high level, is a negative for growth. From our 2015 post on their study:

Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening were positive only up to a certain point, and after that point, increased depth became a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefit of more complex and extensive banking systems topped out at a comparatively low level of size and sophistication.

The only way to keep a bigger financial system not to act as a drag is via strict regulation, something in absence these days.

Now to turn to the main event. There is so much compelling and carefully argued detail that it’s hard to know which bits to showcase. And I do strongly urge you to read it in full.

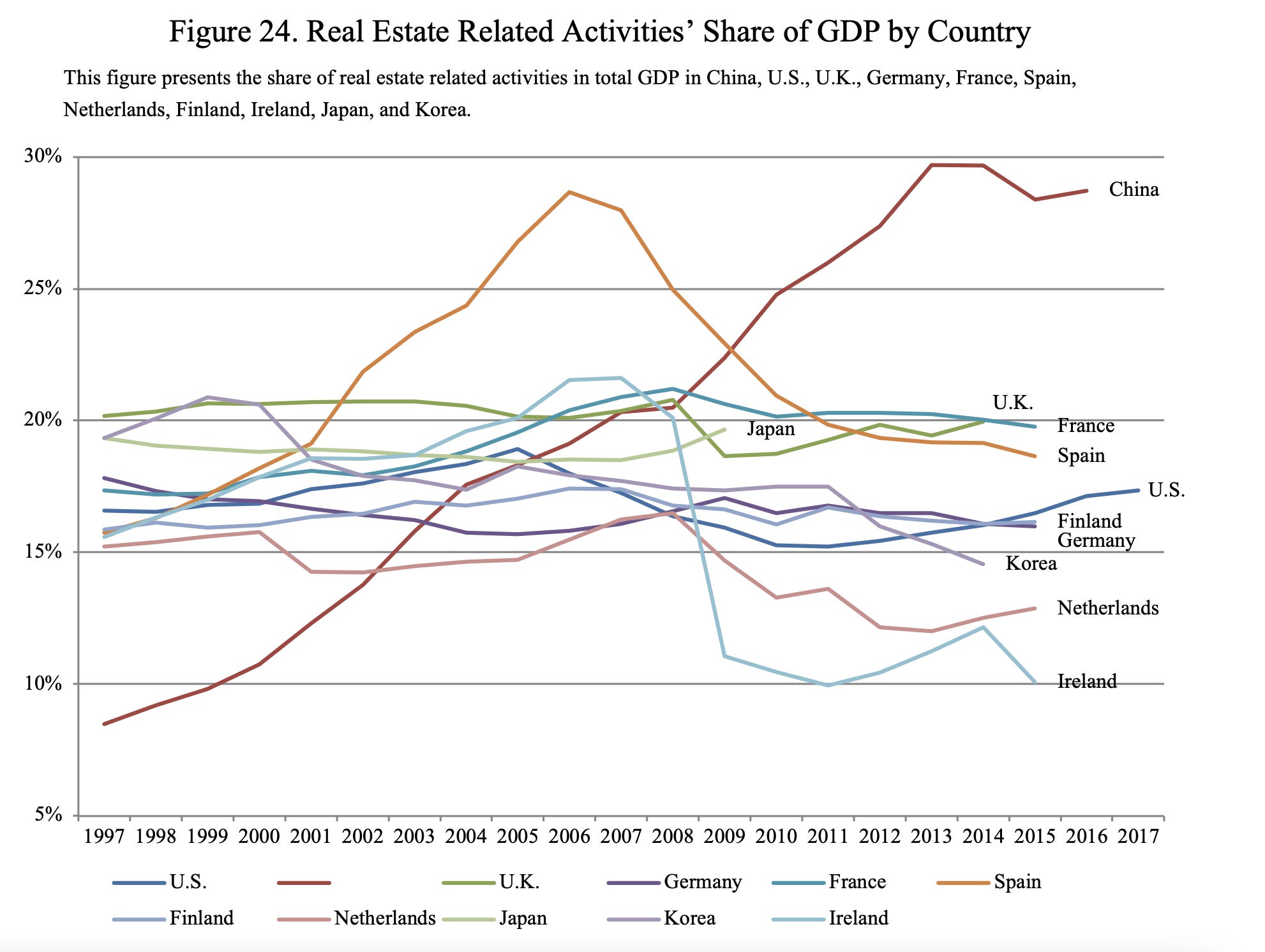

Sine starts with the attention-getter that China’s FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) sector was already a bigger proportion of GDP than that of the US as of the mid-teeens: 8.5% in the US in 2017 versus 9% in China in 2015, per the deputy director of the Finance and Economics Committee of the National People’s Congress. The official, Yin Zhongqing, recognized this was not a desirable development:

…with the fast expansion of the money supply, vast volumes of funds have cycled back into the financial system, vast amounts of liquidity have never entered the real economy…and ‘casting off the real for the empty’ [脱实向虚] has grown more intense.

This sounds an awful lot like the massive capital flows in Japan that Western bankers swooned over in the mid-later 1980s, and the 2006-2007 “wall of liquidity”. And he invokes that image:

Retirement savings collected from households by institutional investors (such as pension funds and other SPVs), trade surpluses and sovereign funds), surplus money resulting from recent quantitative easing policies and the rise in accumulated profits of transnational companies in tax havens have all created a wall of money that gradually pushed for the financialization of built environment.

In China, FIRE is nearly all real estate; even seemingly normal manufacturing companies are very often heavily involved in development projects (and not as builders). In a rare sour note, Sine depicts the driver as a savings glut, when that line of thinking comes out of the bogus loanable funds model, that loans come out of savings. In fact, it’s the reverse: banks lend out of thin air, creating deposits. So what Sine is really saying is there is more lending than productive outlets. That is also what we saw in Japan in the mid-1980s, when among other things, companies could (and did) borrow 100% of the fictive value of urban land (fictive because it virtually never traded; selling land was regarded as akin to selling your children, an admission of bankruptcy). Similarly, as we explained long form in ECONNED, the pre-global-financial-crisis wall of liquidity resulted from the massive gearing of heavily-synthetic subprime CDOs.

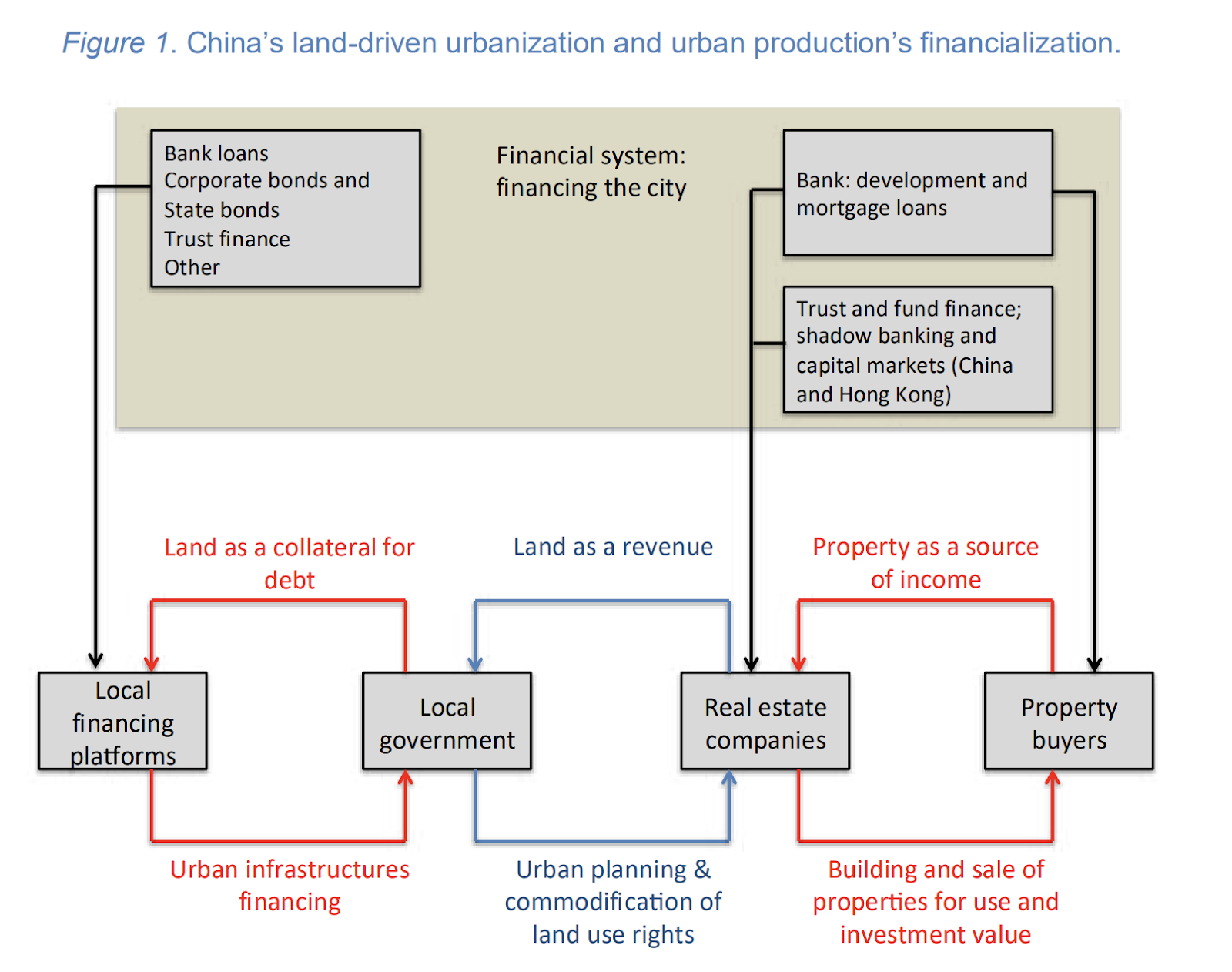

This schematic shows how it works:

China has a savings rate of 50%, highest in the G-20, and mainly from households and non-financial companies. This lends some support to the complaint that China does not consume enough. Economic activity is sending more income and revenues to workers and their employers, but they aren’t plowing it back into the system by buying things, but by investing/speculating in real estate to an excessive degree.

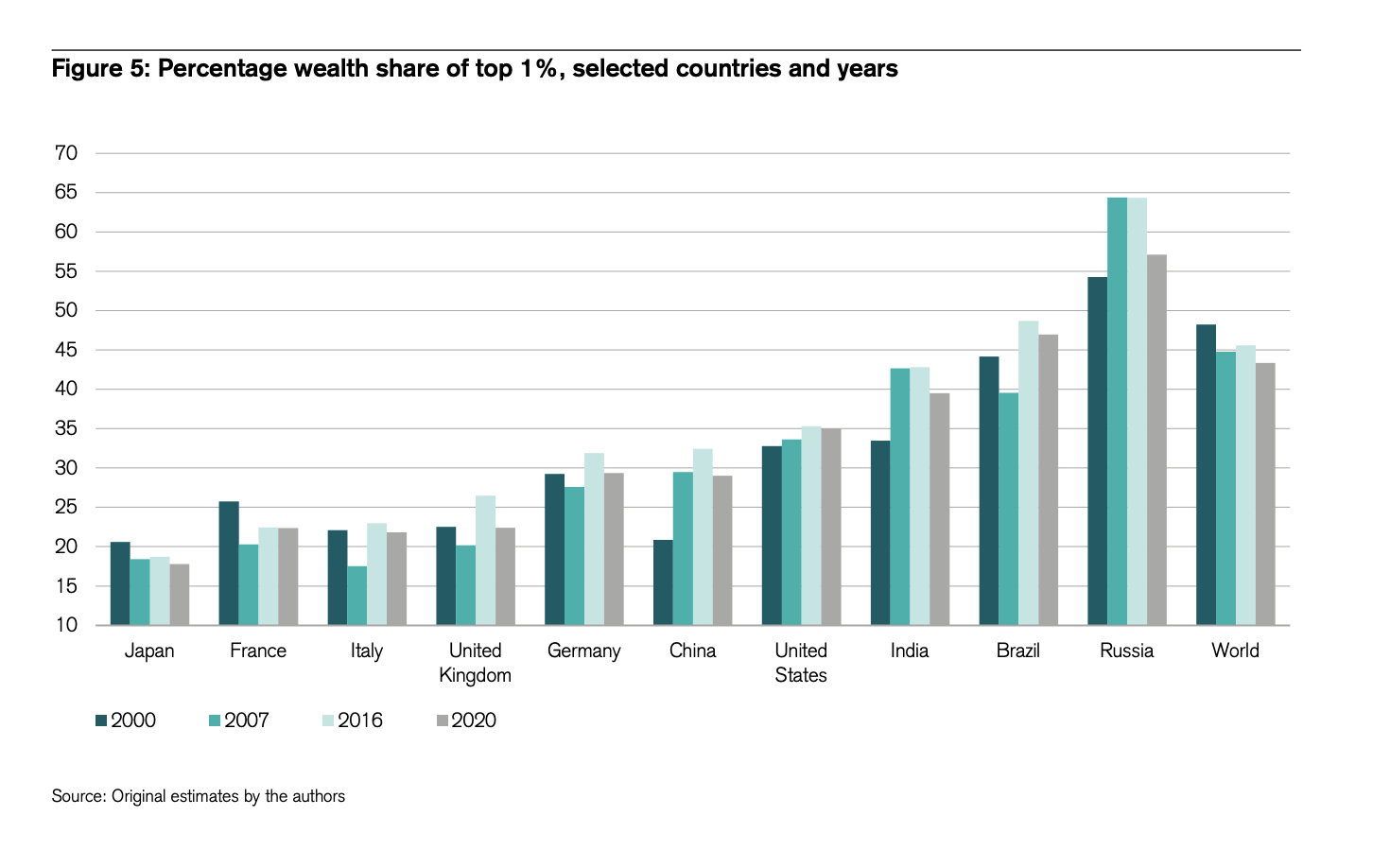

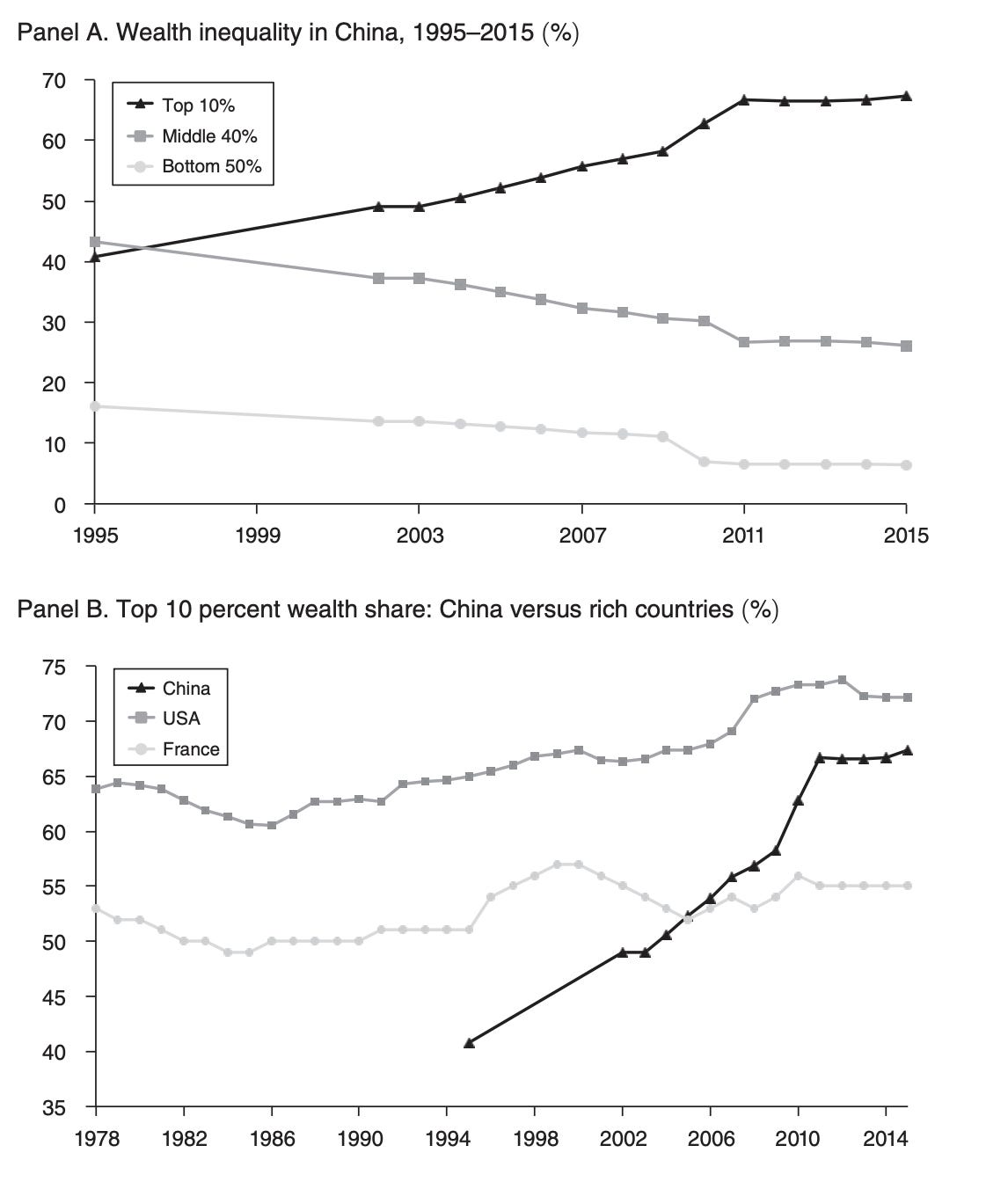

Another sign of financialization is the rise in wealth disparity, with China approaching US levels”

Additional measures:

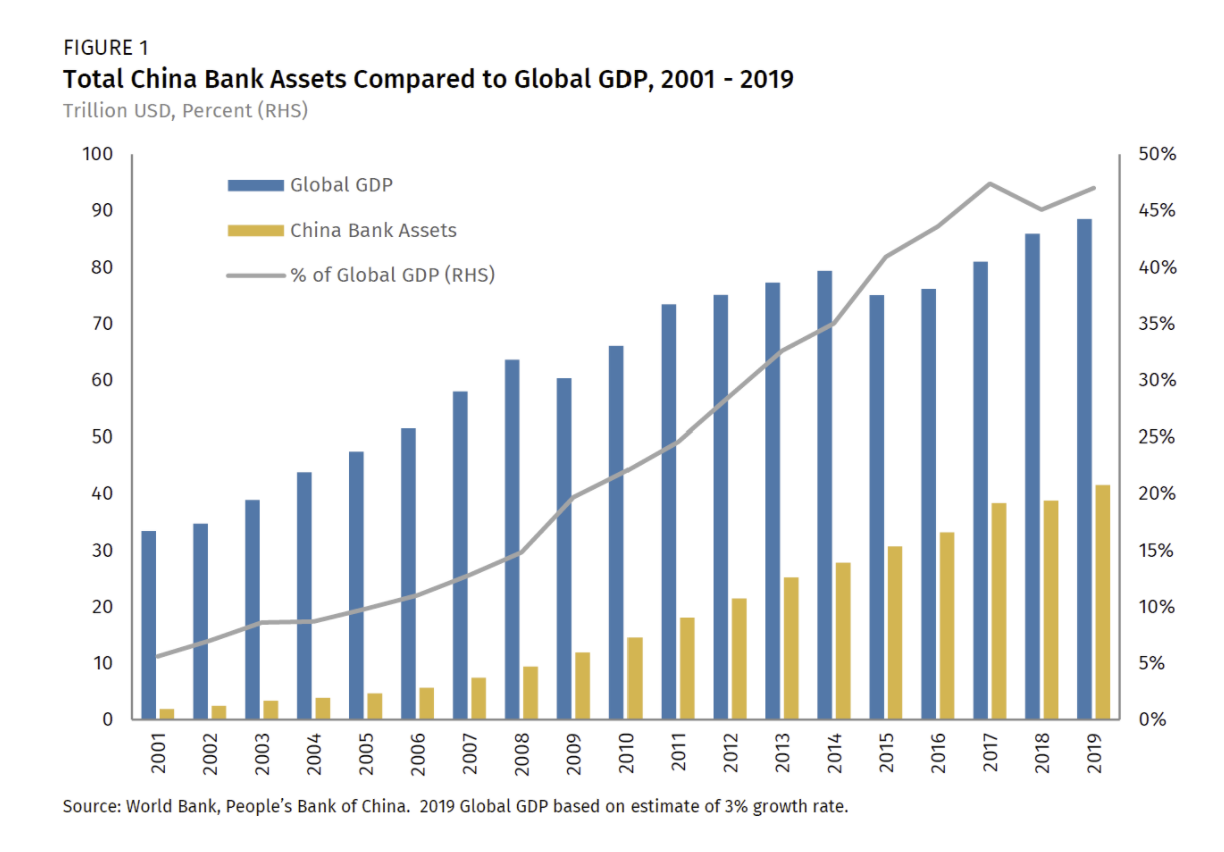

Sine then turns to loan and financial system growth, which if you were of the “loans create deposits” school of thought, you’d put first:

Logan Wright and Daniel Rosen have written extensively on the topic, and in a recent note in 2020 try to frame the stunning numbers in a comprehensible fashion. The PRC’s financial system

“has increased in size by 4.5 times since the global financial crisis, rising from 64.2 trillion yuan ($9.4 trillion) in assets as of the end of 2008 to 292.5 trillion yuan as of last month ($41.8 trillion). To put the current value in context, it represents about half of global GDP. In the same interval, China’s GDP roughly tripled in size, adding around $9 trillion in annual output.”

Here is the phenomena in graphic form:

The US banking system is $21 trillion. So, in terms of raw financial system size, that problem is worse in China.

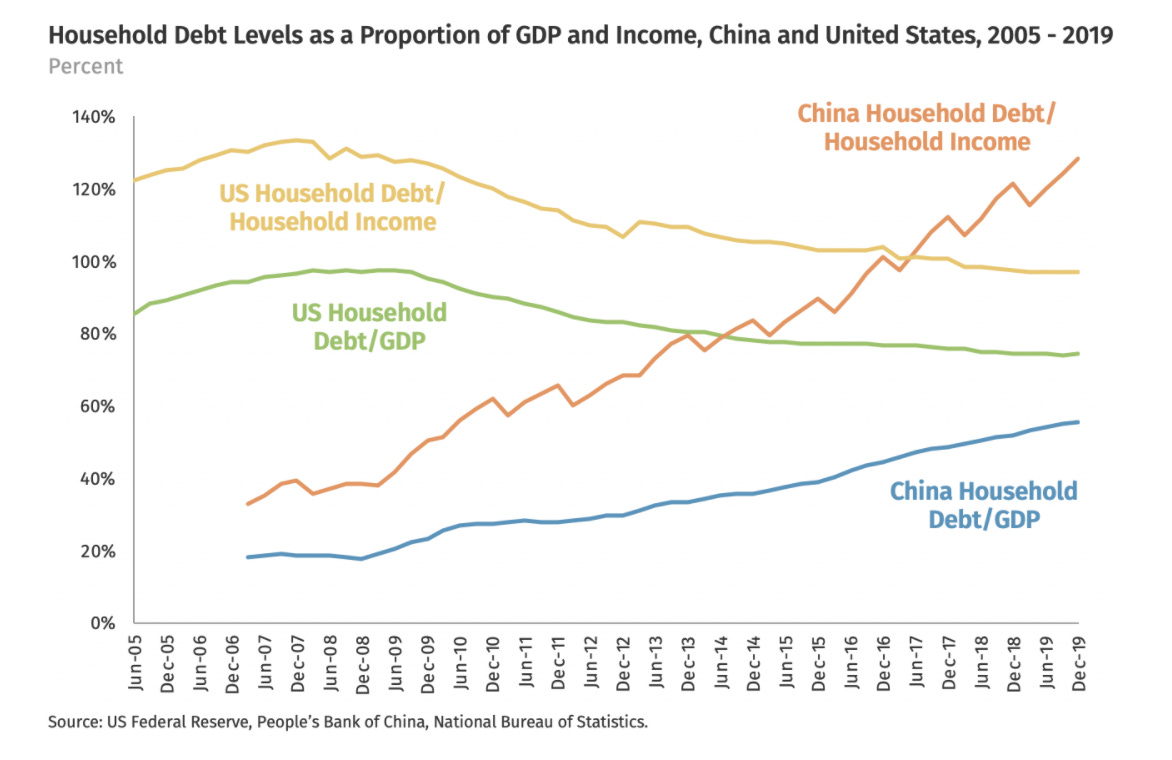

Household borrowing is also very high for a country that is only at best on the cusp of being an advanced economy:

Remember, China does not have America’s student debt overhang or much use of credit cards and therefore presumably only pretty trivial credit card debt. But apps hand out microloans like candy and young borrowers reportedly fall prey to them. They do finance car purchases, but not as frequently as in the US.

But all the household dough is going overwhelmingly to real estate, with it accounting for 80% of typical net worth, versus 35% in the US. That much money going into property has unbalanced the entire economy:

There’s even more evidence in this post, but the extended recap above will hopefully prove to be persuasive. We’ll stop here and again suggest you read it in its entirety.

And yes, the update via Sine’s deep dive into local government financial vehicles only adds more grist to this view. We hope to turn to that tomorrow.

PlutoniumKun/Sine…thank you for more eloquently expressing some concerns that have crossed my mind.

Will be interesting to see any rebuttals.

My suspicions revolved around the sameness of the education of the global PMC and that there is an elite class consciousness that spans the globe.

The reference to Japan made me think of this eye-opening documentary:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5Ac7ap_MAY/

Princes of the Yen | The Hidden Power of Central Banks

So, apparently, this is simply what money does when it is not subjected to best use policies. As in best for the planet. I think so far best use has been focused on profitability prospects no matter what the politics. But then ‘Best use’ is a common term when it comes to real estate development. And clearly 1.5 billion people will support the usual real estate feeding frenzy. What is to be done? Let’s ask the planet. Let’s redefine ‘profit’ before it gobbles up everything.

The US and China suffer from bloat at the top and make those at the bottom by its downward pressure suffer from it, too.

I recently read in RT an essay that an economy’s commitment to financialization is an off-ramp to oblivion with consequences for all those implicated in it. The article’s focus is on the US:

Death of empires: History tells us what will follow the collapse of US hegemony https://www.rt.com/business/594432-financialization-death-empires/

I’ll be looking for an assessment of financializaion in Russia. On the face of it, the war in Ukraine has simultaneously strengthen the Russian economy and trashed Europe’s. (Economist Michael Hudson opined just after the war’s beginning that the whole point of US sanctions on Russia was to bring Germany down; Germany was the workhorse that pulled the EU’s wagon. Think of the impact of paying 4x [mainly to the US for LNG] as much for natural gas on industrial and household economies.) Russia–and India–may end up being the last ones standing.

So what is it, over-financialization or the real estate sector had an overwhelmingly large role in China’s economy? If it’s the later, then the situation is being mitigated with the recent deflating of the real estate bubble.

Exactly, and unlike the UK, US etc., China has an economy still growing at 5% of GDP per annum. Add on a little bit of inflation and thats 7% per annum nominal, doubling every 10 years. So, if house prices remain stable for 10 years they will halve relative to GDP and incomes; and that goes for the debt related to them also.

Financialization is when the private finance sector becomes the dominant economic player, but the core of the Chinese financial system is owned and controlled by the Party-state, and the Party-state has already taken a number of measures to rein in the private financial sector (e.g. with the taking down of the Ant Group financial empire).

Whom, exactly, owns/finances all this Chinese real estate? The Chinese middle class or the PRC? In the US, since 2008, residential real estate is now being controlled/purchased by private equity. (A recent Link in NC said it takes ALL of a families income to purchase a median priced home.) Is comparing China’s financial standing to the US comparing an apple vs. orange?

The deflating of the real estate sector in China is the destruction of ordinary Chinese peoples life savings. This is why the housing sector simply cannot be allowed to fall back to anything close to a real valuation.

The other key issue – as the article explains – is that high land valuations are central to local government finances. Falling real estate means massive local cut backs in expenditure without Beijing intervening – and Beijing has made it clear it won’t intervene. This is creating enormous problems at a local level, with no end in sight without very radical change – essentially China requires a complete revamp of its taxation system and internal transfers. This level of change is not without cost.

I read the article – charts, graphs, and sums in the billions tend to make my brain go all late-nite-tv-white-noise. But my gut tells me “right tight that one” (not that I would ever dream of letting my gut think for me, I’m no ruminant me nossir/ma’am).

By which I mean to say, thank you PlutoniumKun for using words that have meaning, and arranging the words into sentences that allow for parsing by the Lilliputian intellects among us. Seems like a connection ought be forged between this and Ms. Smith’s writeup about Yellen goes to China – somethingsomething “financial stability” somethingharrumph. Is there a carrot hidden in that bundle of sticks?

Taking your six sentence summation at face value, sounds like the Chinese gov’t takes the position of “if a battle cannot be won don’t fight it.” Which sounds like laissez-faire economics… with Chinese characteristics?

Just because people are rightly aghast at the inequality, financialization, and plutocracy that exists in the West, many naively fall prey to knee-jerk approval of the Russian and Chinese economic models simply because they are the designated adversaries by the USA/Nato/etc.

This article finally points out how capitalism and the pursuit of profits, no matter how it is marketed (kindler/gentler euro flavor, predatory american style, or socialism with chinese characteristics), results in basically the same terrible outcomes for the 99%….massive inequality, the complete remaking of society for the 1%, and the destruction of public goods/services.

The graphs do not lie. Chinese inequality has increased markedly and Russia is even worse.

“China’s growth rate is flagging or overstated, and contend that that has knock-on effects, particularly making it difficult for China to deliver rising standards of living”

You can raise standards of living by increasing wage levels faster than those components that are required to increase your standard of living – housing, clean water and food, health, transport, energy. You can increase the standard of living while wages remain flat by lowering the cost of components that are required to increase your standard of living – housing, clean water and food, health, transport, energy.

When you open up to speculation – or burdening with finacializations asset price inflation (interest on debt or securitized debt) the cost of components that are required to increase your standard of living – housing, clean water and food, health, transport, energy will necessarily go up to cover the exponential growth of compound interest – and always reduce the standard of living until ……crash – civilization and the economy …. this economy designed for short term gain instead of designed for humans and long term sustainability

I’m puzzled by the wealth distribution graph based on “original estimates by authors.” There Russia is far and away the most skewed to the 1%. Searching on Gini coefficient tables has them more in the middle range, e.g. within hailing distance of other countries in Europe (anachronism?). What gives?

My laymans take, and someone correct me if I’m wrong, is that having rode the finance and real estate trains as far as they feel they can, the government of China is now attempting to switch entirely to a solid foundation of physical industry.

It’ll be a rough transition, maybe a few years of reduced growth (and yes, I’m well aware all the Chinese growth numbers are inherently suspect, but it seems irrefutable they’ve enjoyed decades of high growth and development. Even if their official numbers are inflated by a factor of two it would still be impressive). But they have, and continue to, invest heavily in actually building things. Factories, the raw materials for those factories, robust transport infrastructure, ludicrious amounts of energy generstion, both renewable and not, all while raising hundreds of millions of people out of basically medieval levels of subsistence poverty (now whether making them factory wage slaves is an improvement is debatable, but on balance their health and quality of life has probably objectively gone up).

You simply cannot convince me there’s any plausible scenario in which the Chinese economy doesn’t enjoy a fundamentally secure future (well, at least until climate change comes for it like it’s coming for every economy).

Sine’s article starts from gross misunderstanding of what socialist economy does for it’s workers. Say,

>“Almost all big manufacturing companies have, to a certain extent, gotten involved in real estate. For many companies sales are stagnant, business is difficult, and the ability to earn a profit has sharply declined, so more and more manufacturing companies have started to subsidize their losses by getting involved in real estate or with financial investments.”

when reading such a thing, you should look back to USSR and remember how state-owned companies had an obligation before their workers to provide them housing. It was a common practice to entice new employees by offering housing shortly after employment, and then there was a common scheme of providing bigger apartments to families who’ve had children.

So, it’s expected that in the face of raising property costs workers would demand SOEs to provide them with housing. And SOEs would do that through building those apartments directly

>Meanwhile, again mirroring the US, income and wealth inequality in the PRC is quite extreme. Credit Suisse’s 2020 global wealth report estimates that the top 1% in China own roughly 30% of the wealth (vs 35% in the US).

This is also gross misunderstanding. Basically, we have a case of arbitrarily assigning wealth belonging to the state to managers of that wealth. There’s also a misrepresentations of shares of a company as ownership of that company, and there’s also the case of presenting shares in shell companies abroad as shares in Chinese companies. Such reading is probably driven by ideological reasons i.e. the need to present China not as a socialist but as a capitalist country to maintain the “end of history” narrative

Regardless, this hand-wringing over China’s real estate is quite comical when we look at the sheer mass of China’s production sector. Rather than trying again and again to recalculate China’s GDP we should rather look at the size of real economy

This one sentence destroys Sine’s credibility:

>Keep in mind that nearly 50% of Chinese people still live on fewer than $10 a day. I can’t find a similar statistic for the US, but given that the minimum wage is $7.25/hr, it’s safe to assume that very few live on less than $10 a day in the US.

To be fair, this particular book is a decade old, but the increasing depth of poverty many people including Americans are unaware of; the current scale of the income and wealth inequality in the United States of America now surpasses the Gilded Age of over a century ago.

There is also the increasing unreliability of official American governmental statistics, which is done to hide the problems, and makes understanding of what is happening difficult. Add the destruction of the news media and the centralization and financialization of what remains also hides the situation.

“Sine’s article starts from gross misunderstanding of what socialist economy does for its workers…”

Keesa,

Thank you so much for writing what is necessary, but what I would be afraid to write. Heck, I am even afraid to have thanked you or to thank you for what is an excellent comment all through.

It is quite revealing that you reacted emotionally to Sine’s argument and explicitly attack him based on ideology when as PlutoniumKun point out, Sine is a non-ideological analyst. So basically, you don’t like someone providing extensive data that China has a very financialized economy, which Chinese officials themselves were warning about back in 2015, that savings were increasingly going into asset speculation.

Oh noes, can’t have that! A socialist economy is every and always better than a capitalist economy. Never mind that 60% of the Chinese economy is privately owned and China has very poor social safety nets, which is the big impetus for its high savings rate.

That is not to deny that China has made extremely impressive progress in development and in raising the living standards of its people over a comparatively short time period.

But this post was not about that. Instead you complain, basically, that it didn’t cover China’s economy from a perspective you prefer, and instead focused clearly on the matter of financialization and what has resulted from that.

Your remark is also a classic example of halo effect bias, of needing people and institutions to be all good or all bad. China’s great growth period does not change the fact that real estate plays an outside role, and the real estate development is integrally intertwined with financialization and rising inequality.

And never mind, as Michael Pettis has described at length, that China’s resolution of its last big bank crisis, in the early 2000s, was put entirely on the shoulders of households. Chinese banks were allowed to offer very low returns on savings products when interest rates were higher, meaning yields/returns should have been at least as high. Pettis has also explained how this resolution had the effect of worsening imbalance in the Chinese economy by undermining consumption. Households would save even more to compensate for the inability to find ways to hold savings that would not be badly eroded by inflation.

So the result is you are simply harrumphing past Sine’s detailed analysis.

And you also straw man his use of the $10 a day level. This is not core to his argument but you haul it out and even then misrepresent both his use and what it signifies.

He was discussing RELATIVE financialization, and relative income distribution, and not poverty.

To address your comment more generally:

1. Real estate has become foundational to local government financing. The decline in real estate prices to still overvalued, but less so levels is wrecking their finances.

2. Real estate investment has been nearly 30% of GDP. You can seriously pretend that having to move away from that in a major way won’t be massively dislocating?

3. China is now a upper middle income country, and so its poverty line should be about $5.50 a day, Wikipedia notes:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poverty_in_China

So 50% earning below $10 a day is quite plausible.

4. With the huge number of Chinese billionaires and wealthy princelings, you are seriously going to try to claim that China does not have a large and growing income equity problem? I see it here in a second-tier city in Thailand, FFS, in the level of Chinese ownership of very flashy seaside condos. Most new condos here are built for the Chinese market, not other farangs or hi-so Thais.

You also present nada in back to your claims about the data, which is admittedly hard to gather anywhere. But in general, the rich are way richer than official stats show because they are good at hiding it.

Almost a new post, this excellent rebuttal! Fo goodness sake, some people do drink the cool aid lol.

So, reading Sine, the adolescent still residing in my reptile brain couldn’t help be chuckle to find that “Wuhu” invented the “vehicle” that, as they do, drove off with China’s money.

If you look at the issues here from a viewpoint of “money as a public good”, the Party’s interest in CBDC could be an indicator it wants to see when and where its’ money transfers (back to localities) go to good vs bad use as a way to float the liquidity of underperforming investments working as collateral for socially useful pursuits. The goal being to manage a selective deflation, allocating costs to non-productive sectors over a managed time frame.

Pure speculation on my part, only a third through the Sine piece.

How much of China’s real estate boom also kept the building industry running?

I remember back in the day people in America laughing because China was building empty cities, and I remember thinking, all-in-all, I would rather have buildings than a bailed out mega-bank. Especially since the mega-bank had nobody go to jail which was Obama’s way of saying “I’ve taken that car you drove into the ditch out of the ditch and bought you a Mclaren F1 so you can do it all again” as he tosses the keys to Wall St and PE.

And it will be interesting to see how China handles financialization. They don’t seem to be the type pf leaders that work very hard to become the dominate industrial power only to flush it all away. If they do something creative there are going to be a whole bunch of countries that have been raped by American finance that may suddenly be interested in working with China rather than the West.

The building industry in China is almost entirely funded by rising land values – the key source of revenue for local governments to pay for all those new bridges and ports is from land sales. Without rising and values, the entire system collapses and needs replacement. Not impossible, but very difficult.

From Wikipedia:

“As of at least 2024, revenues from personal income tax are 6.5% of China’s total tax revenues.[2]: 6 The Chinese government’s tax revenues are primarily from indirect taxes such as the value added tax.”

With taxes going from 3% of income to 5 of income.

The social safety nets are so and so, with a lot of out of pocket expenses — out of poverty program in China involved mostly schemes to provide work and productive streams of income to the poor and less governmental payments.

As such, the population surplus is ill managed/invested.

LGFV = Local Government Financing Vehicle

“They call it a ‘vehicle’ because it’s designed to drive off with your money.” –Long Ago Atrios commenter

Given the size of China’s manufacturing sector, and the US manufacturing sector and that the total economy must add up to 100%, its hard to square with China having a larger or similar FIRE sector – I recall how many analyses proved Russia has an economy the size of Portugal, but suddenly its the largest in Europe.

Personally, I think western (capitalist) economists have trouble valuing the state sector. At its basis is how economic activities including state activities that are not market priced contribute to GDP.

So where does massive US corruption (big pharma) and outright theft ( US leadership positions) to US (GDP) economic strength. Or prisons? Are prisons a service, a leveraged rent-extraction financial tool, or part of the manufacturing sector for underpaid slave labor? Obviously crime is FIRE because of insurance, or is it a service as it supports police and sends customers to the medical industrial complex, tax payer funded. And if the way GDP is calculated is fairly nonsensical, how can assessing percent contribution to GDP be sensible.

That said, I am sure China will have FIRE inspired troubles that it will deal with, but it also has solid infrastructure, whereas the west has FIRE inspired troubles and decaying infrastructure, manufacturing ability, and growth rates accompanied by massive debt levels.

Facebook doesn’t work without hardware to run it on. Just sayin’.

I’m fine with this article. It says just what I’ve been saying in China.

Idid indeed say that China does not have the financialization and FIRE sector problem that the US and West has. It has its OWN FIRE sector problem. That’s what all my lectures in China are about.

One great difference is that China creates money and credit. It is able to write down debt with quite a different set of vested interests complaining.

There’s only one way to minimize the wealth inequality that these charts show. That’s to write down the debt. That will let some banks and companies and individuals go under. China can do that and survive.

At least it doesn’t have a systematic use of corporate debt to pay dividends, to buy stock to support its prices. It just debt-financed asset-price inflation — that is the common denominator. And it’s also China’s failure to tax land rent and other economic rent. That concept has not become mainstream, despite the fact that it was central to Marx (Vol. 3 esp.)

I’ve sent this article to my Chinese colleagues. I’ll let you all know what they say.

As always, thanks so much for engaging on topics like this.

I agree absolutely that the debt needs to be resolved in the manner you’ve always argued for, and this is not beyond the capacity of Beijing to manage. The problem as I see it is that the entire system has taken on a life of its own, which may make it politically impossible to resolve in a sensible manner. Too many people at too many levels profit from the status quo.

There is also the practical issue of the massive complexity of local loans – as one Chinese friend of mine put it ‘everyone in my village owes money to everyone else’. I’ve no idea if it’s even possible to track adequately the loans to ensure some sort of moral hazard. It would be an epic task to identify the loans that are appropriate for writing down.

You mention Marx, but as the article points out, China also has taken something of an anti-George approach to this, with its very light touch on land taxation, but weak property rules.

I’m thinking the difference is that China may not yet have a whole growing industry composed of basically very smart and highly educated people who do little more than play online poker all day.

US has a whole fundamentally unproductive and inflationary fantasy economy, parasitic on a shrinking real economy, funded by low-no interest rates, that includes an extensive home based network of self employed former industry professionals and their self employed home based trainees.

Most of these people would be better redeployed to work on something productive, like supply chains, instead of blowing paper (really, electronic) asset bubbles all day that support the ability of paper asset holders to spend like there’s no tomorrow.

Needless to say, this is state supported.

Very interesting.

I have just one comment. Figure 5 ‘wealth percentage of top 1%’ which is accredited to ‘the authors’. This seems to contradict the wealth studies made by the likes of UBS annually. Which have China dominating the ‘mid-range’ wealth globally, and relative to say the US the top 1% is a very small percentage.

However Hong Kong in the latest UBS report does reflect the percentage in Fig 5, and I wonder if this has been extrapolated by the author across China as a whole, which would be misleading.

Otherwise I don’t find it surprising that China exhibits the same sort of problems encountered by other economies. As Prof Hudson says , it has the ability to deal with these ‘growing problems’ without great injury overall.