Yves here. Even though it seems apparent that military contractors benefit from war, there’s still some utility in proving that out formally, as George Georgiou has below.

Some readers might quibble with using General Motors as the basis for comparison, since non-Chinese carmakers are floundering. Boeing is in notably bad shape and has a large defense business, so it could not serve as a comparable. Perhaps John Deere? That might make the arms merchants look a less advantaged, but I doubt it would change the conclusion, particularly given the structure of US military contracting, which virtually assures profits to the supplier.

By George M. Georgiou, who worked for many years at the Central Bank of Cyprus in various senior roles. I wish to thank Martin Gallagher for detailed comments which challenged my initial assumptions. I also thank Tony Addison and Yiannis Tirkides for helpful comments. All errors are mine.

Introduction

The concept of an economic beneficiary of war may sound unconscionable given the scale of destruction, death and grief that conflicts often result in. However, even in the darkest of times someone, somewhere will benefit. These beneficiaries can include the black market merchants who provide food and other much needed supplies, whose normal channels of distribution are disrupted. It can also include mercenaries who sell their services to whichever side in a conflict is willing to pay the ‘market’ rate, and above. But the beneficiaries are not confined to those acting in a nefarious capacity. The most obvious beneficiaries are the arms manufacturers.

The assertion that arms manufacturers benefit from war is neither novel nor new. It would be counterintuitive in the extreme if we didn’t expect arms sales to increase during periods of conflict. The main purpose of this note is simply to present some data which might offer support to the argument. A secondary objective is to contrast the fortunes of the arms manufacturers with those of the non-arms manufacturers, and in this endeavor General Motors is considered as the representative non-arms manufacturer.

The Arms Trade

Tables 1 and 2 below show the top five arms exporting and top five arms importing countries, respectively.

Table 1 – Top 5 Arms Exporting Countries, 2019-2023

(million TIV)

- USA 58,393

- France 15,283

- Russia 14,760

- China 8,117

- Germany 7,982

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

What is TIV? Trend Indicator Value(TIV) is essentially a volume measure which quantifies the transfer of military resources from one country to another. SIPRI prefers this to a value measure because calculating the latter requires the use of data provided by governments and industry bodies. SIPRI argues that there are serious limitations on such government data. Specifically, there is no internationally agreed definition of what constitutes weapons and there is no standardized methodology concerning how to collect and report such data[1].

Given the economic and military hegemony of the US, which translates into a propensity to instigate wars directly or through proxies, Table 1 offers no surprises. Such is the volume of US military exports that during the period 2019-2023, it exported more than the total of the next four largest exporters, which includes Russia and China.

In Table 2, two countries are worth commenting on. India is shown to be the leading importer of weapons for the period 2019-2023. Given that India’s domestic arms industry is relatively underdeveloped, this is not surprising. However, its dependence on imports is likely to lessen as Modi continues with

Table 2—Top 5 Arms Importing Countries, 2019-2023

(million TIV)

- India 13,754

- Saudi Arabia 11,715

- Qatar 10,668

- Ukraine 6,896

- Pakistan 6,053

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

the implementation of his 2016 Defense Procurement Policy. With regard to Ukraine, prior to the current war it ranked significantly lower than the 4th place shown in the table. Between 2019 and 2021, its arms imports averaged only 31.33 TIV but in 2022 this increased to 2,789 and in 2023 it reached 4,012[2]. It is likely that the 2024 number will be significantly higher than this.

The Arms Manufacturers

Table 3 below gives a snapshot of the total revenue and market capitalisation of the top five arms manufacturers, all American. The table includes General Motors for comparison purposes. Although GM is no longer the behemoth it once was it is still a significant manufacturing company. In 1953, Eisenhower nominated Charles Wilson, then president of GM, to the post of Secretary of Defense. At the confirmation hearings, Wilson was asked about the possibility of a conflict of allegiance between GM and the US government. Wilson responded as follows:

“I cannot conceive of one because for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country. Our contribution to the Nation is quite considerable.” (my italics)

In the September 21, 2010 issue of 24/7 Wall St, Douglas McIntyre pointed out that in 1955 GM employed 576,667 staff and accounted for 50% of the American car market. Recent data show that by the end of 2023 the number of employees had fallen to 163.00 and its market share was only 16.9%. However, GM is still the largest US car manufacturer and is thus a good benchmark for comparing the performance of the US arms manufacturers.

Table 3—Top 5 Arms Manufacturers and General Motors: Total Revenue,

2023 and Market Capitalisation, 2024

(USD billion)

Total % of revenue Market Cap.

Revenue from weapons

Lockheed Martin(US) 67.57 90.0 115.90

RTX Corporation(US)[3] 68.92 59.0 155.34

Northrop Grumman(US) 39.29 90.5 68.67

Boeing(US) 77.79 40.0 135.21

General Dynamics(US) 42.27 71.4 73.18

General Motors(US) 171.84 – 59.68

Sources: SIPRI Top 100 Arms-Producing Military Services Companies in the World, 2023, companiesmarketcap.com

Arms Manufacturers, Conflict and the Economy

Table 4 below presents employment numbers for Lockheed Martin(LMT) and Northrup Grumman(NOC) as well as GM. The choice of Lockheed and Northrup is based primarily on their overwhelming reliance on arms sales(see Table 3 above).

Table 4 – Total Employment at Lockheed, Northrup and General Motors,

2017–2023

LMT Growth% NOC Growth % GM Growth%

2023 122,000 5.17 101,000 6.32 163,000 -2.40

2022 116,000 1.78 95,000 7.95 167,000 6.37

2021 114,000 0 88,000 -9.28 157,000 1.29

2020 114,000 3.64 97,000 7.78 155,000 -5.49

2019 110,000 4.76 90,000 5.88 164,000 -5.20

2018 105,000 5.00 85,000 21.43 173,000 -3.89

2017 100,000 3.09 70,000 4.48 180,000 -20.00

Sources: Macrotrends, Stock Analysis

Whereas manufacturers such as GM have experienced long-term decline, as expressed by several metrics, including the number of staff employed, arms manufacturers have been increasing their headcount and revenue thanks to a thriving demand for their products. And this is reflected in the response of investors. As Wayne Duggan wrote in US News in 2024:

“Not surprisingly, leading defense stocks have performed relatively well in recent months. Shares of unmanned aerial vehicle company AeroVironment Inc. are up nearly 30% in the past six months. Military aircraft part-maker TransDigm Group Inc. shares have traded higher by 32% since Hamas attacked Israel. Through Jan. 29 this year, the stock prices of defense giants RTX Corp. and Textron Inc. are up more than 7% each, while the S&P 500 is up just 3.3%” (“How Do Conflicts and War Affect Stocks?”, January 30).

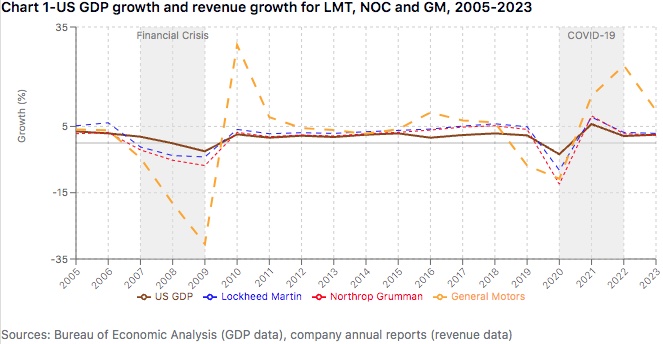

Chart 1 shows the revenue growth of Lockheed, Northrup and GM set against US GDP growth for the period 2005—2023. There were two significant events which impacted GDP growth—the financial crisis of 2007–2009 and the Covid pandemic in 2020. During the financial crisis, US GDP growth was either stagnant(0.21% in 2008) or declined (-2.6% in 2009). Although there was some impact on the armaments sector, car manufacturing recorded sharp falls in output, revenues and employment. As Bill Dupor at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis wrote in 2019:

“One of the hardest-hit sectors during the most recent recession was autos…New vehicle sales fell nearly 40 percent. Motor vehicle industry employment fell over 45 percent. Faced with bankruptcy, Chrysler and General Motors were bailed out by the U.S. government using TARP funds. At one point, the federal government owned 61 percent of General Motors” (5 July).

During the Covid pandemic in 2020, GDP in the US declined by 2.77%. Again the impact on the arm aments sector was far less significant than on the car sector. Indeed, Lockheed’s and Northrop’s revenues in 2020 actually increased by 9.34% and 8.74%, respectively, whereas GM’s revenues fell by 10.75%.

Looking more generally at the entire period depicted in the chart, GM[4] has shown far more volatility than LMT and NOC. The armaments sector

represented seems to be more stable and resilient than the car sector. This shouldn’t be surprising given the nature of the products sold by arms manufacturers and the markets in which they operate. The US doesn’t just provide arms to its client states when they are at war, they also arm them in preparation for the next potential proxy conflict. The list of recipients/purchasers of US weapons is long–Israel, Taiwan, Turkey, the Philippines, the Gulf States, Egypt, South Korea, Australia, etc—and the military hardware(and software) is abundant[5].

Conclusion

In his 1970 classic chart topping hit, War, Edwin Starr sang:

War, huh, yeah/What is it good for?/Absolutely nothing

If only. The song’s anti-war lyrics, written by Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield, contrast sharply with the reality of the military-industrial complex(MIC) that views war as a financial opportunity. Eisenhower’s original 1961 framing of the MIC, and its potential to circumvent and distort the agenda of democratically elected governments, was drafted with the Korean war behind him, the Vietnam war simmering, and Afghanistan, Gaza, Iraq, Libya, Serbia, Ukraine, Yemen, and other arenas of conflict, yet to come.

_________

[1] For many years, the US State Department published an annual report on Military Expenditure and Arms Transfers(WMEAT). All data were in value terms. Following the repeal of the 1994 statutory provision requiring the publication of WMEAT, the State Department ceased publishing it in 2021.

[2] Figures may not add up due to rounding by SIPRI.

[3] Includes Raytheon.

[4] Plotting revenue growth for Ford shows the same pattern as GM. NOC’s revenues fell in 2009 for a variety of reasons not directly related to the 2007-9 recession.

[5] See, for example, the BBC report “The US is quietly arming Taiwan to the teeth”, 6 November 2023

In my experience, there are 3 kinds of people;

(1) Those blessed souls who, both, forgive and forget..

(2) The average person who forgives, but does not forget.

(3) And lastly, the endless nightmare evoked by the person who never forgets and never forgives.

Avoid #(3) like the plague……….

We wouldn’t need weapons if everyone was in the forgive and forget camp.

The best thing for the arms manufacturers is that the weapons that they make don’t even have to work that well or even at all. So long as the fix is in, government leaders can be ‘persuaded’ to buy any sort of dodgy weapon going. Case in point. Here in Oz we were looking to replace the venerable F-111 – which was a twin-engine jet with long range and could carry heavy loads – with a similar fighter to suit the needs of our large continent. So what we bought was the F-35 – a single engine fighter with short legs and limited carrying capacity. Makes sense. Look at some of the weapons that the US has spent umpteen hundreds of billions of dollars on – LCC ships, F-35s, Zumwalt destroyers, Boeing V-22 Osprey helicopters, Ford-class carriers, Boeing KC-46 refueling tankers but you get the idea. Basic stuff like 155mm artillery shells they were cutting back on as there was not enough profit margin and wanted to build hyper-expensive high-tech shells instead. Smedley Butler was right. War is a racket – but in ways that he may not have thought of.

The really funny thing is that there actually is an excellent replacement for F-111 available on the “free market”, Su-34.

What if countries stood up to the war machine and refused to be Krupp’d?

The NZ Air Force got rid of their fighter jets around the turn of the century and didn’t replace them~

Missiles and drones are certainly cheaper than an air force of manned planes. Both can be build in country.

An air defense system is harder to build but Iran, China, RF can get it going enough to suppress manned planes…

Homo ‘sapiens’ : ironic, or paradoxical moniker.

All the innocent beings that perish due to our really objectionable nature- disheartening.

Epitaph: too much head, too little heart.

The U.S. MIC exhibits many symptoms of racketeering::

– Compulsory purchases to secure “protection” (NATO, ANKUS)

– Shoddy goods at inflated prices (LCS, Osprey, F35)

– Bribery of officials to secure contracts (D.C. revolving door, foreign payoffs)

– Obscured finances (regularly failed DOD audits)

Unfortunately, militarism is so deeply rooted in U.S. culture that we will continue to suffer from this slow poison indefinitely. The most we can hope for is avoiding a global nuclear war.

I really have no idea what the point of this is. There is an enormous difference between the motor vehicle sector and the defence sector. In the latter, the only formal customer is governments, the market is hedged around with political and legal limitations, and major nations try to manufacture as much defence equipment as they can themselves. In the case of the US, it’s next to impossible for foreign companies to get a significant share of the market. In the case of the car industry this is not true, and foreign manufacturers have been devastating the market for years. Likewise, people bought fewer cars during Covid, but what the author probably doesn’t realise is that armaments contracts go on for decades and are not impulse decisions, hence little affected by transient problems. In the case of Ukraine, only a small number of contracts have actually been placed with US industry and it’s not clear if any money has been handed over. So what’s the point of the comparison? And I have never heard of this SIPRI measure, nor is it clear in fact what the measure measures.

I think that if the armaments industry was a major driver of war, we’d see far more wars in the weapons exporting rather than the weapons importing countries, but I’m not really sure this is the case – although arguably its in the exporters interest to stoke up wars far from its borders.

There is also a very big additional complication in that for many countries (not least the US and Russia), the military and weapons manufacture represent a key economic tool for both regional assistance, overall Keynesian economic management, and a source of hard currency. Contrast this with France, where arms exports are mostly about maintaining the scale of manufacture required to keep domestic weapons costs down. And of conversely, a lot of arms importation has little to do with war, and everything to do with buying influence (hence the gigantic and highly varied purchases of Qatar and KSA).

I think its probably more appropriate to say that there are certain sectors who have an interest in stoking up conflict – but this is far more than just weapons manufacture – after all, the origin of much or our financial industry can be traced back to the requirements in centuries past for Kings, Emperors and others to keep raising finance for various wars, and this led to many of the ‘innovations’ for good and ill in our modern financial systems.

I shared this the other day… — please watch “Deal of the Century” with Chevy Chase from 1984. For an entertaining and poignant angle and to confirm that nothing much has changed since then… It’s got all of this covered!

When one looks at defense spending, it is the most expensive on a per job basis, and at the end of the day, you do not have roads, or cars, or anything of use.

If I recall correctly, GM severely limited domestic goods production and transitioned to become the largest military contractor during WW II. It is noted that the attrition of the Ukraine war and the mismatch between Russian and US/Western arms manufacturing proves that the ability to wage “industrial warfare” is still important. The atrophy of GM and other domestic manufacturers make it difficult for the US to fight another major war against peer opponents Russia and China able to surge arms production.

Funny how Russia has a smaller industrial base and smaller defense budget and out produces the entire NATO at a fraction of the cost. Har har.

It is obvious that China/Russia organize their military industrial complex much differently than NATO. It is organized to produce what is needed without a profit.

NATO’s MIC is organized to produce a profit first, what is needed is not really even a second or third priority. F35 planes, Patriot air defense, UK aircraft carriers are prime examples. It does not matter that GM industrial capacity exists or not. We just destroyed EU/NATO auto/truck industry in the last 2 years, it makes no difference to NATO MIC before or now they still can’t produce anything.

Yes, the profit motive in American MIC seems to override everything else. Money spent on this without reform of that basic fact is almost a complete waste, it cannot make enough and it’s effectiveness is very questionable.

For WW2, American heavy industry was able to convert mass production to producing the required material, but I think American industry has lost that capability due to JIT and outsourcing everything else except for a very limited in-house support capability. Plus, government control and monitoring of profiteering that worked in WW2 is completely gone; it’s now pretty hard to even figure out who is more corrupt, the MIC corporations or the elected government officials.

Spending whatever trillions would be required to put an Iron Dome defense in place over America is idiotic given that it was so easily penetrated by Iran over Israel, but it’s gonna make billionaires even more rich so it’s very likely to happen.