Yves here. We are posting below on an overview of the massive Pacific Palisades and environs fires. Even though there have been quite a few climate-change-related disasters, such as more frequent and extensive wildfires and more intense and locationally unexpected storms and resulting floods, the destruction of so much high value real estate might lead to even bigger shifts in insurance policy prices and even “access” to coverage.

Even though the headline speaks of a crisis, insurers may be able to roll with the current crop of disasters. They reprice their premiums annually and property and casualty insurers by reinsurance to cover exposure to large events. So they might take hits but these incidents, at least near term, should not imperil their businesses.

However, the impact on property values in high climate risk areas is another matter, particularly since real estate near beaches or in wooded areas, or even as we see now in Los Angeles, on hills (as in good views) that make them more exposed to high winds and thus catastrophic fires, has historically been prized and thus has commanded healthy prices.

The knock-on effects of scarcer and more costly home insurance will be large. Home ownership has been a, arguably the, way Americans accumulate wealth. Most buyers finance their purchases. Banks require home insurance, and in perceived-at-risk areas, also stipulate that the policies cover flood risk. Fire damage, which is a standard covered risk, will almost certainly lead home insurance to become more pricey in perceived-to-be-exposed areas. The same will be true for insurance for commercial buildings.

In the not-too-distant future, certain areas will effectively be red-lined from a flood or fire insurance perspective, either formally or by having policies be so expensive as to be unaffordable, or having terms that limit coverage in the event of wildfire or flood losses? What happens to those properties when the only market is cash-only buyers (or much smaller mortgages, limited to the maximum that insurers will cover), and then ones who understand that they are at risk of bearing the full or large losses?

And consider: what happens to current home borrowers if they can’t meet the obligations in their mortgage to maintain adequate home insurance?

This shift over the next few years means a big reset in how insurers, and following that banks, assess and price risks, with resulting reductions in value to affected properties. Business Insider looked at how this shift is under way:

- Some homes affected by the Los Angeles wildfires might not have insurance.

- Insurers have been canceling plans and declining to sign new ones in the state.

- Years of worsening wildfires have increased payouts and other costs for insurers in California.

…..State Farm, for instance, said in 2023 that it would no longer accept new homeowners’ insurance applications in California. Then, last year, the company said it would end coverage for 72,000 homes and apartments in the state. Both announcements cited risks from catastrophes as one of the reasons for the decisions.

Homes in the upscale Pacific Palisades neighborhood, one of the areas hardest hit by the fires so far, were among those affected when State Farm canceled the policies last year, the Los Angeles Times reported in April

The article later describes how the state insurer nevertheless plans to force insurers to offer coverage. Good luck with that:

A new rule, set to take effect about a month into 2025, will require home insurers to offer coverage in areas at high risk of fire, the Associated Press reported in December. Ricardo Lara, California’s insurance commissioner, announced the rule just days before the Los Angeles fires broke out.

Obviously, insurers can largely vitiate that requirement via high prices, particularly for new policy applicants. And in the light of the ginormous Los Angles fire, they can contend the pricing is risk-justified.

Changes on the insurance front are still very much in play, but California’s ABC7 gives a flavor of what is in the offing:

Part of the governor’s state of emergency includes an insurance non-renewal moratorium. The state’s insurance commissioner told our colleagues at KABC Wednesday that he’s working on protecting homeowners in the affected areas from being dropped by their insurer for one year.

It’s raising serious questions about how these fires will influence California’s growing insurance crisis.

As we watch the devastating wildfires move through Los Angeles County, it’s posing new threats to the state’s growing insurance crisis. With more than 13,000 homes at risk, losses could approach at least $10 billion, according to preliminary estimates from JP Morgan Chase. This paired with concerns as the state is implementing a new reform plan that analysts say could raise insurance premiums by 40% on average. In fire-prone areas, the increases could be up to 100% or more…

The commissioner’s plan is implementing what is called “catastrophe modeling,” which uses software algorithms to assess risk and make decisions on your coverage. So anything from having a fire in your area, to poor mitigation, to lack of staffing at your local fire department — they could all impact your ability to have coverage. It’s an issue we’re seeing in Pacific Palisades… and right here at home.

The city of Oakland just announced they are going to close five fire stations because of their budget crisis, one of the many factors insurance companies consider in the data that they access.

Needless to say, this is not reassuring.

Now to the main event. Lambert will have some more updates in Links, but a quick look at one aggregator says things are getting worse, with fires in Hollywood Hill and Laurel Canyon and Sunset Boulevard closed.

By Bob Henson. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Prolonged, top-end bout of damaging winds will hit parts of Southern California from Tuesday to Thursday, January 6-8. The winds themselves could bring serious havoc, knocking down trees, limbs, and power lines. An even bigger worry is fire: the fierce gusts will scrub a landscape parched by one of the driest starts to the water year in Southern California history, so any wildfire that gains traction could be devastating. Update (11:30 p.m. EST Tuesday): The situation in northern parts of the sprawling Los Angeles area was rapidly deteriorating tonight, as the Palisades Fire and Close Fire were growing rapidly and moving southward toward heavily populated neighborhoods that rarely see a high-end fire threat. More than 30,000 people were being evacuated, including across large parts of Santa Monica and Pasadena.

As of midday Tuesday, gusts of 84 mph had already been recorded on Magic Mountain, just north of the San Fernando Valley, and 50 to 70 mph gusts were already becoming widespread. A fast-moving fire had erupted by late morning above Pacific Palisades, quickly growing to 200 acres before noon PST.

Strong winds in Pasadena pushing 60 MPH, with gusts in the hills to 80 MPH. @NWSLosAngeles pic.twitter.com/f9d6VCi9qD

— Edgar McGregor (@edgarrmcgregor) January 7, 2025

The worst is likely to play out late Tuesday and on Wednesday when parts of Ventura and northern Los Angeles counties can expect “extremely critical” fire weather, the highest possible category in outlooks issued by the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center.

Communities at the greatest fire-weather risk lie along the north side of the San Fernando Valley and into the adjacent higher terrain, including Santa Clarita, Simi Valley, Moorpark, San Fernando, and La Canada Flintridge.

Critical fire-weather conditions (just one step down from “extremely critical”) will extend over a much broader area, possibly affecting millions of people from the greater Los Angeles to San Diego regions and into the Inland Empire. Widespread wind gusts in the 50 to 80 mph range will extend all the way to the coast in some areas, especially north of Los Angeles, and gusts could range as high as 100 mph in the mountains and foothills.

“Given the intensity of the winds, extreme fire behavior appears likely should ignitions occur,” warned the Storm Prediction Center in an outlook issued early Tuesday.

Strong winds are coming. This is a Particularly Dangerous Situation – in other words, this is about as bad as it gets in terms of fire weather. Stay aware of your surroundings. Be ready to evacuate, especially if in a high fire risk area. Be careful with fire sources. #cawx pic.twitter.com/476t5Q3uOw

— NWS Los Angeles (@NWSLosAngeles) January 7, 2025

The preconditions for a January fire in Southern California couldn’t be much worse. After two years of generous moisture (especially in 2022-23), the state’s 2024-25 wet season has gotten off to an intensely bifurcated start: unusually wet in NoCal and near-record dry in SoCal. We’re now in weak to marginal La Niña conditions, and La Niña is typically wetter to the north and drier to the south along the U.S. West Coast, but the stark contrast this winter is especially striking. Two cases in point, looking at rainfall from October through December 2024:

- Eureka, CA: 23.18 inches (12th wettest in 139 years of data; average 15.27 inches for 1991-2020)

- San Diego, CA: 0.14 inches (3rd driest in 175 years of data; average for 1991-2020 was 2.96 inches)

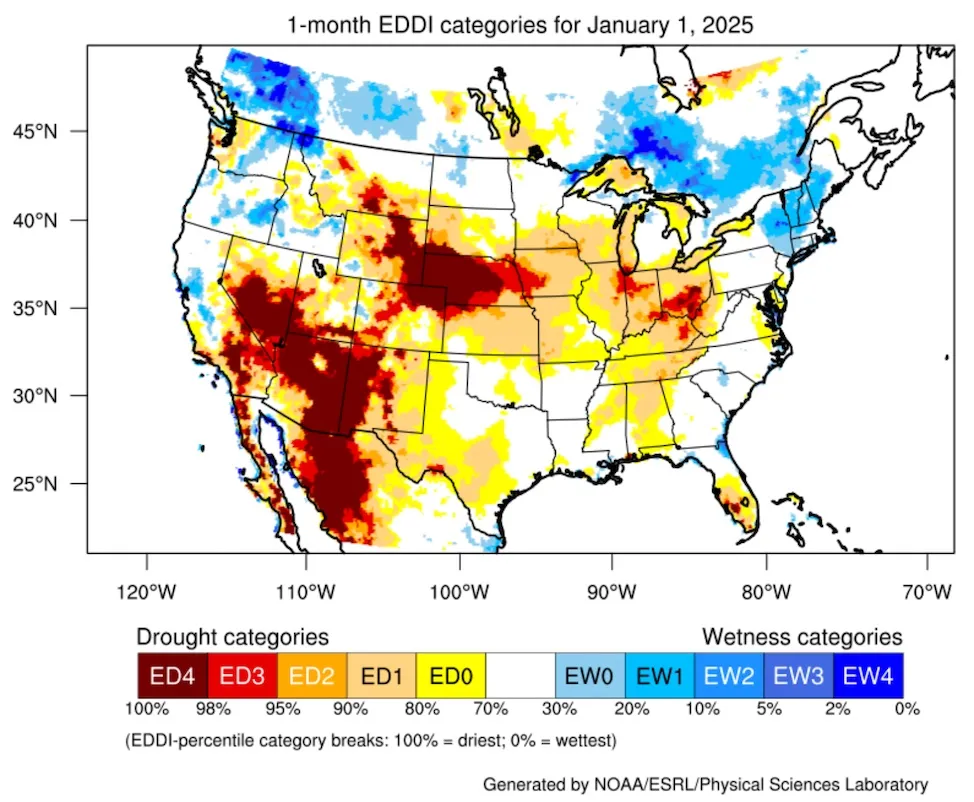

Southern California had not yet pushed into severe to exceptional drought as of December 31, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. But the landscape has been drying out quickly, as reflected in Fig. 1 below of the Evaporative Demand Drought Index (a measure of how “thirsty” the atmosphere has been over a given time frame).

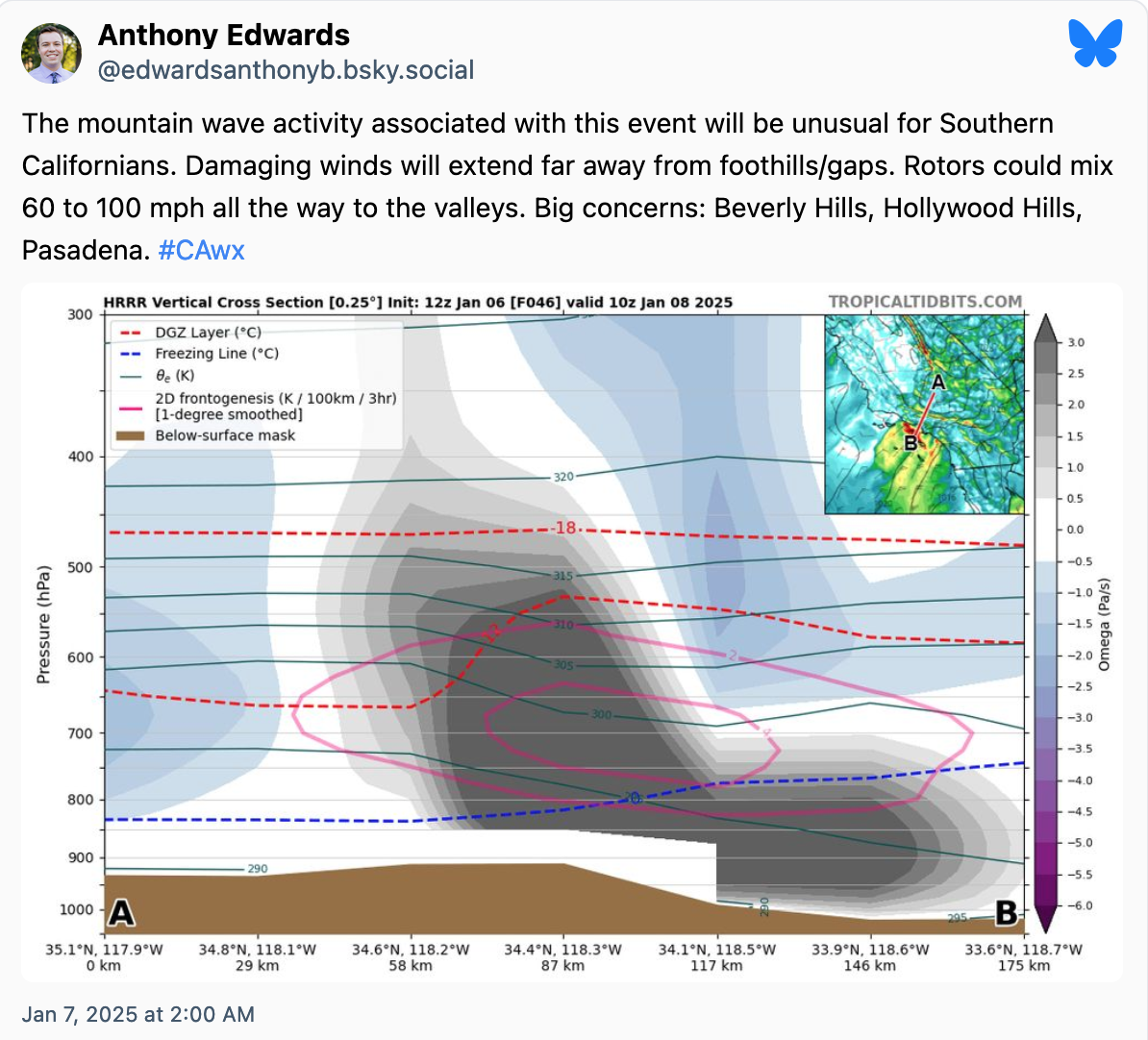

On top of the unusually dry conditions for early January, we’re now in the heart of the Santa Ana wind season. These notorious and dangerous downslope winds, which occur when higher-level winds are forced over the coastal mountains and toward the coast, typically plague coastal Southern California a few times each year. This week’s peak winds may arrive more from the north versus the northeast, compared to a classic Santa Ana event, and the associated wind-bearing mountain waves (which are shaped by the vertical temperature profile at mountaintop level) could punch further toward the coast than usual.

The National Weather Service warned that this could be the strongest Santa Ana wind event in Southern California in over 13 years, since Dec. 1 2011, when Whitaker Peak (elev. 4120’) in Los Angeles County recorded a gust of 97 mph (156 km/h). The winds toppled thousands of trees, and over 200,000 homes lost electricity, mostly in the San Gabriel Valley towns of Altadena and Pasadena

There’s no research indicating that downslope winds like this are becoming more intense or frequent with human-caused climate change, or that we should expect them to. But it’s abundantly clear that fire season is lengthening in Southern California, as documented in this 2021 study by California weather expert and climate researcher Daniel Swain, and it’s likely to continue stretching out (see this 2022 study). These shifts will open the door for summer-dried vegetation to stay parched and highly flammable until the winter rains arrive (even if that’s after New Year’s Day).

Although this week’s setup isn’t unusually warm, higher temperatures overall are making droughts more dangerous by allowing more water to evaporate from landscapes and reservoirs.

Clarity Corner: The Problem with “Hurricane-Force Wind Gusts”

There have already been media references to this week’s Southern California winds possibly delivering “hurricane-force wind gusts.” This term can be misleading, though. Hurricanes are defined as tropical cyclones with sustainedwinds of at least 74 mph (65 knots or 119 km/hr). But the peak wind gusts in a given hurricane are typically 20 to 30 percent higher than the top sustained wind. So a minimal hurricane with 75 mph sustained winds can be expected to produce peak gusts in the range of 90 to 100 mph.

Where this gets tricky is that wind gusts of 75 mph or more are sometimes referred to as “hurricane-force.” But it doesn’t take a hurricane to produce such gusts. Even a tropical storm with top sustained winds of only 60 mph can do the trick. Moreover, the winds in a mountain-related downslope windstorm are typically far more variable than in a hurricane, sometimes even going from near-calm to peak strength in a matter of a few minutes. So keep in mind that a Santa Ana windstorm with peak gusts of, say, 80 mph – while still fearsome and highly dangerous – wouldn’t pack the same wind punch as a Category 1 hurricane.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

WUI is me with both of my domiciles in the forest for the trees being in the line of fire, and it isn’t as if the insurance companies haven’t noticed, my primary residence having gone from $2400 to $6300 a year in insurance premium.

If they cut me loose or try to up it to $10k a year and I let them loose, its a loose-loose deal either way.

I’m guessing most home-owners will feel the pain. One silver lining to having my palace being a pimped out shotgun shack is it just won’t cost that much to rebuild if it comes to that.

That the victims of the fire are mainly made up of the wealthy and very wealthy is an interesting turn of events. This fact may expose some hypocrisies in the system as the story evolves. The payouts are going to be enormous. People used to getting their way will find themselves battling the institutional power that they have to date succeeded living with, even embraced as their own.

What of the insurance industry? Probably a bailout on the way. We 21st century USians have proven our talent for tuning out when it’s “lessons learned” time, or perhaps institutional learning is not from a perspective of Jo Citizen’s well being.

Oh, as an aside, I believe landslides can and do follow fires in this sort of terrain, so hope for rain, just not too much all at once. I’m feeling pretty bad for these people.

I mentioned yesterday how many in the entertainment industry would lose their residences, just as Hollywood was in the death throes of its importance, and not merely entertainers, but all of the support people involved as well.

A local in Tiny Town is a set guy in tinsel town, and a combination of CGI, cost cutting, Covid, strikes and more has laid him low.

He mentioned to me that he only has 35,000 hours of experience on the job, but its almost as if it doesn’t matter anymore.

The Great Depression killed vaudeville, and all the factors I’ve mentioned are doing in Hollywood.

Homes were worth $3 to $10 million in Pacific Palisades, and do they get the SVB sweetheart deal in getting bailed out?

FEMA on the way with the $750 checks?

The WNC debacle could be a guide to future events. :(

Would the Amish come all the way to the coast to build tiny homes? :)

Given that LA represent one of the most housing short markets in the nation, I was wondering if the rebuild would cause an increase in housing density. Pacific palisades probably not. Altadena maybe… Rail access to dtla and density was not terrible to start with.

Insurance companies, isn’t the point that they should be charging for risk and a single year of losses, even massive, should be covered by invested returns?

CA resident with multiple properties mostly self-insured, they will burn, tiny houses which cost less than $20k to build so I can afford to rebuild.

M

The debris will no doubt flow. John McPhee’s book ‘The Control of Nature’ has an entire section on LA’s attemped mitigations on that score..

Hope you and yours stay safe through this siege!

Wonder how much of your $6300 has been going to fund mergers and/or stock buybacks.

My brother has a McMansion in Kenner, LA a few miles from the airport. Hurricane Ida 3 years ago stripped off part of his roofing shingles. It was many a $25,000 job. He was already paying $10K. After Ida the insurance went up to $60K, so he dropped it. Flood is separate and subsidized.

We pay about $600 a year for a 4BR on acreage. I much prefer shoveling snow to hurricanes, wildfires or earthquakes. There were pretty good reasons why the rustbelt was the center of population and industry.

Even those with coverage face criminally large deductibles and delays in payment…

I’d like to make two suggestions and ask the readership to comment.

1.a sprinkler system: a desalination plant supplying a county wide sprinkler system for use in drought conditions

2.hiring people & ground mounted drones to weed out invasive plants on a regular basis

Yes both suggestions are very expensive. The alternative may be more expensive.

Some expensive homes have their own fire-safety sprinkler systems, or even a hydrant . . . but if everyone is trying to save their own home at once, there’s no way to deliver enough water pressure to make it work.

Swimming pool might be dual use on site water reservoir to pump. Goats are used some places for decent brush clearance. Other ideas are roof/vent hardening (embers get sucked in and the set fire from inside) and appropriate landscaping i.e no cedar right next to the house but gravel instead

If you look at the wildfire mitigation plans of the big 3 investor owned utilities, you will find that “vegetation management” is already a major expense (possibly second only to under grounding of lines). Regulators will only aprove so much advanced mitigation, because at a certain point, it becomes cheaper to go another route.

I also believe (i.e., have heard through the grape vine) that many of the defense arguments in the Camp Fire were related to improper vegetation management on the side of property owners. After all, landscaping decisions are not generally publicly administered but certainly impact the ability of fire to spread through a community.

Maybe those areas that become uninsurable because of the repeated fires will simply be rezoned so that poorer people can live there but there will be no requirement for them to have their houses insured. if they have money enough t build a house, then all risk lies on them. I would not be surprised if this eventually happened.

I am not so sure those areas will be rebuilt, as eveything is gone: schools, shops, roads, services, hospitals. Dust and ashes on the shore: another Gaza on your doorsteps.

I’ll take the other side of that wager. Sounds like a developers dream.

A word from the world of distressed debt; One person’s disaster is another’s opportunity.

Yes, I expect private equity to purchase many house lots in Palisades from oldsters unwilling/unable to fund reconstruction. They have the time and money to do the lengthy design review process involved with rebuilding.

Finding enough building materials and contractors will make rebuilding pricey.

Please, do NOT misinform readers. This is absolutely not what private equity does. They buy EXISTING homes and EXISTING businesses. They do not engage in construction or any direct business operation.

Coastal California has rebuilt after plenty of catastrophic events before. 1906 SF Earthquake/Fire, 1989 SF Quake, 1994 LA quake.

Beyond La La Land many US cities have a large fire or three some time in history.

A lot of what was lost was 70-85% land value, 15-30% structure.

I do wonder how many of the well off will move to Palm Springs, Tahoe, Vegas etc.

From the other thread

It’s not the Eastern Bloc. Virtually the entire world sees the logic of putting people in multi-unit housing made of non-combustible materials.

NZ, AU, Canada, and the US are the bad kind of exception.

On the other hand, concrete production is environmentally unfriendly, depleting sand resources and scarring the land, (while ‘good’ sand is getting scarcer – only certain grain types are useful) and it is also bad from an emissions viewpoint. Timber housing using renewable sources is carbon-friendly and more pleasant to live in. However they need to be used in appropriate locations, as ‘GM’ points out.

Wood really is not a good building material from a climate perspective. When it burns, the carbon and particulate release is very large. And most lumber is grown in tree farms, which is overhyped in terms of greenhouse gas reduction: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-53138178. Even worse is the portion harvested from wild forests.

On the contrary, wood is an almost perfect building material, if it is produced in an environmentally sensitive and sustainable way. There is no reason why timber used for housing should be burned, unless it is not used in ‘appropriate locations’, as I agreed above. The reference you cite is full of qualifications, which I mostly agree with – it should not be used as a blanket nullification of the idea of using timber at all, as you seem to imply.

Your claim is false. You need to provide links with evidence, and not unsubstantiated opinion.

The point is the one made by GM above: “If you insist on building single-family homes out of wood, and surrounded by trees and shrubs, well, then you are extremely vulnerable to precisely this kind of event.” We now have swathe of fire-vulnerable California full of precisely this sort of housing.

Your point about wood talks past the fact that we are living in a different world in terms what communities are now exposed to high levels of fire risk.

From Wood Is Not the Climate-friendly Building Material Some Claim it to Be:

https://www.wri.org/insights/mass-timber-wood-construction-climate-change

Sorry, this is all quite irrelevant, being based on the assumption that “trees are standing forever”. They dont. They grow and decay as every organic matter does, and release the CO2 stored beforehand in the process. Quite without any human interference. Spending some time in between as a doorpost doesn’t change matters.

Sustainable forestry manages this in a way that never more is used than grows in the same span of time. Indeed, the term sustainability, German “Nachhaltigkeit”, was coined in connection with forestry. In central Europe, managed forests have been used in this way for centuries, with no detriment to the climate at all. Forested area has been increasing ever since the middle ages, the wood content increasing because many owners have been using less than is recommended for maximum growth.

That said, it is true that the big help in mitigating climate change is not by using wood as carbon storage but rather as a substitute in things hitherto made from oil and gas, wood being regenerable in quite a shorter span of time than fossile ressources.

A wholesale condemnation of using wood in building and furniture will not help keeping our forests in a good and healthy shape. People tend to care more for things that profit them. At no cost for society. Whereas owners need to be compensated if they forsake using their property AND there is no product society needs and has to find other sources. loss-loss

This straw mans what I said and talks past the point GM made above. Wood burns and when it does so, it results in massive carbon releases. It is an unsuitable material to use for housing in fire prone areas. Climate change mean that areas that were only at low fire risk are very much exposed

For a rather more accurate analysis of the qualities of wood, here is a scientific analysis, rather than a BBC journalists report:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666165920300260

See the discussion I provided. Yours omits key factors like what happens to the parts of the tree harvested but not used in building.

These analyses completely omit the impact of catastrophic home fires on the environment, and the issue we are now seeing in Los Angeles: that wooden single family homes are a perfect environment for catastrophic fires to develop and spread, and the greenhouse gas and particulate impact of the burning of that wood, and the additional impact they have on the scope and intensity of wildfires.

There are some research efforts recently started, such as: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/fire-protection-research-foundation/projects-and-reports/the-environmental-impact-of-fire

It will never cease to amaze me that Americans and Canadians can be so brainwashed about wood being a good building material, something that any child who had read The Three Little Pigs would shake their heads at.

It’s even crazier than the idea that our governments have the self-evident right to police the earth.

But there are “scientists” who will tell you otherwise in both cases!

Planned obsolescence. Start accumulating homebuilders and Home Depot stocks now!!!

The key element is the erratic weather patterns in California. Santa Anna wind events are what forces the fire deep into the suburbs. The homes in Altadena are older, smaller homes built in the 1940’s. Rebuilding them today will be very expensive.

I think replacing these older homes with more modern (energy efficient) modular homes would be the way to go. Many of the Altadena homes have similar foundation patterns amenable to a few standard floor plans conducive for a modular structure.

With the foundations and infrastructure already in place a modular construction could accelerate reconstruction of whole neighborhoods with some federal/state subsidy. Cities are going to see budget deficits unless there is a rapid rebuild—to replenish property taxes.

From a City & County Property Tax perspective this could be a win with longtime owners locked in with 1980s or 90s Prop. 13 rates turning over for new folks with a 2027 or 2028 assessment.

On Twitter they were saying that a new law allows homeowners who lose their homes to catastrophe to retain their grandfathered tax rate if they rebuild within 2 years…I forget the weird Orwellian term they came up with for this insane idea.

Of course the existence of discriminatory property tax rates is as much reason as the wildfires for any sane person to stay out of California.

What if all the suburban detached houses had all been built out of commie concrete? With metal or tile or whatever roofs? And zero wood permitted anywhere within the structure of the house.

( Decades ago I spent a summer working for a landscape company in Saratoga Springs, New York. We mainly mowed the lawns of the rich people. But one find day, the owner took us out to his father’s rural lot and building-in-progress house. The exterior walls were up and they were all poured concrete. One wall had several slit-window spaces in it, about 3 feet tall and several inches wide. I said ” you know , those look like rifle ports.” He said . . . ” yeah . . . ” )

Neoliberal brain rot prevents the populace from realizing that taxes ARE insurance, and definitionally the cheapest form since it captures the largest cohort possible.

Hilarity ensues …

Some billionaire was getting dragged on Twitter for saying “heads should roll” for not preparing better…but he had been advocating for tax cuts right up until then.

One hopes his house burned all the way down.

Perhaps we might draw upon the ACA as a model to fix the property insurance crisis to ensure insurance corporations future profits – APIA – the Affordable Property Insurance Act. This would pave the way for further consolidation of insurers so they can move towards monopoly and change if they feel like it, of what they decide to cover and even then not cover what they cover if they don’t want to pay out claims. Plus a big government welfare fund for the companies if don’t make a profit. It’s time people who want homes put some skin in the game and thus a way to do it. Plus, we have the added benefit of experience with the ACA, so we know we might also include government subsidies to corporate CEO’s for personal security forces from any ungrateful citizens.

It’s too early to know, but if the point-of-origin for these fires can be determined it will help make an informed cause determination.

Scenarios like this were gamed out inside the wildland world more than two decades ago. The thinking then was it would be Islamists with flare guns, a weather forecast, a basic knowledge of fire behavior, and no fear of getting caught. But this was all before drones…

That aside, there were several reasons why the people who settled this land tended to avoid (or remove) the picturesque when it came to trees and shrubs around their dwellings, and fire was near the top of that list. Sadly, much of the 21st Century looks to be spent re-learning everything that was understood for all the centuries leading up to the latter half of the 20th.

I notice that, among the risks insurance companies are reportedly taking into account, building practices and materials are not mentioned. In my experience the most they do is give you a minor discount on your premium, sort of a “throw a dog a bone” attitude.

Yet you can find videos online where AAC (autoclaved aerated concrete) walls, or even stick frame homes with fiber cement siding do quite well in fires that burn down everything around them. Of course there is more to it than that–roof design, land clearing, and even the type of windows you have can play a role–but it does seem like there are options much less likely to burn in a fire. And in subdivisions, every home built this way will reduce the risk of a fire spreading or starting in the first place.

But I think we need standards and certifications before insurance companies get behind this. And before that we need research, to see which combination of improvements are really necessary. And probably we need state support, meaning some kind of promise from the state that if too many certified fire safe homes go up in flames the insurance companies’ liability will be limited, in exchange for guaranteed lower rates for these homes.

All of this is doable, though…right? But until something is done I fear that the threat to communities from rising insurance premiums may actually be more catastrophic than any one fire.

LA got a wakeup call in the 1936 Long Beach earthquake. It caused a big upheaval in construction codes, and zones along faults were singled out for special attention. Between that and landslide and expansive soil and cliff ablation issues, you can’t build in the metro area without serious ground investigations and mitigation where necessary.

So it could certainly be done again with new regulations for fire-resistant dwellings, although it would add a new cost burden for compliance, when California already has a high burden for compliance. But what do you do with all the existing millions of buildings? Especially ones owned by lower income people already overpaying for mortgages, and with no discretionary income to play with.

Houses are becoming residences of the ultrarich who will be able to self-insure. For everyone else, there will be state-owned and state-insured communal housing with a rent deducted directly from your income like a tax. Give it another 50 years or so.

Or will the tent cities just grow instead?

There must have been a reason for first nations using mostly tents.

Higher minimum deductibles as an offset to the coming higher rates may be required also.

I’ve always had $5000 min deductible on my CA homes (2) as a cost offset.

As inflation whips up prices of homes, all associated costs must rise. Feature not a bug.

Wonder how many solar systems and batteries were extinguished?

Anyone see Peg Leg Sullivan on the scene?

Since insurance companies have gone to the trouble of identifying areas at high risk for natural disasters, shouldn’t the federal government take this opportunity to subsidize and encourage the relocation of homes from vulnerable areas to safer ones?

Unfortunately, the Santa Monica mountains is a chaparral habitat that relies on fire and floods as a natural cycle. Here’s a report from 1995 that covers this and how development can be better suited for such an area:

California Coastal Commission Natural History of Fire & Flood Cycles

https://www.coastal.ca.gov/fire/ucsbfire.html

So the fire issues associated with this area have been known for quite a while, but we’re beginning to understand that climate change is going to cause conditions which can significantly increase these risks meaning that our current sizing of all the emergency systems in place (fire department sizes, crews, equipment, fire hydrant, water reservoirs, etc) will be inadequate when a major event occurs.

But we’ve watched this play out for years now. Is anybody in state or federal government taking about up sizing emergency system preparedness, infrastructure improvements, FEMA rescoping it’s mandate to prepare our citizens for climate change? Heck, we’re having a hard time getting money to maintain what we already have so that’s a big no. And judging by how well it’s going in Maui, and Asheville, it’s a double big no.

But Biden’s pretty out of it, maybe we can convince him this happen in Ukraine and get $10 billion or so.

In that vein, there’s Mike Davis’ classic, The Case for Letting Malibu Burn.

. . . ” What happens to those properties when the only market is cash-only buyers (or much smaller mortgages, limited to the maximum that insurers will cover), and then ones who understand that they are at risk of bearing the full or large losses? ”

I wouldn’t dare to predict what will happen to any specific properties. But I suspect that over the next few decades, the whole Fire Ecology Chapparal zone of California will become a zone of megamillionaires living in the most beautiful places and simply replacing a mansion every time it burns . . . and huge numbers of tarpaper-shack favelistas living in all the less scenic gulches and mid-to-lower hillsides and etc.

Brazilifornia here we come!

Sure, it’s an insurance crisis as long as citizens in FL are allowed to build on the beach, citizens in NC are allowed to build on flood capable areas of rivers, and citizens in CA are allowed to vote in politicians who refuse to clear underbrush and cut firebreaks for the benefit of environmentalist-nutters in a manner science (forestry management) suggests is prudent.

Moreover, with regard to FL (where, as it happens, I reside), it’s become a crisis because politicians forced citizens who don’t live on the beach to underwrite those who do. This, in exchange for political donations by those living on said beach. And in rebellion, those whose home are paid off drop their homeowner’s policies (e.g. the many retirees who own their homes outright and don’t live on the beach), which has put Citizens (the state scheme) into a cash crunch (such that they’re not paying claims, a whole other imbroglio presently blowing up in slow motion on the Governor and the Legislature).

About the only ones for whom it’s a genuine crap shoot is fire (not CA) and tornadoes. even hurricanes don’t much matter in FL if you’re not right on the freaking coast but inland a bit.

From what I have read ( and the very tiniest bit I have just barely seen), the Chapparal of Southern Coastal California is not like the forests of the South, East, Midwest or even the Mountain West.

” Clear the underbrush”? There is no distinct “underbrush” there to clear, because there is no “overbrush” of genuine trees semi-shading the “underbrush”. It is all a bunch of various shrub-height/ shrub-form brushy shrubby brushery. And it doesn’t burn like the “wood” and “brush” of other places. It burns hot like oil. The Chapparal plants are mostly covered with various kinds of waxes, resins, oils, tars, etc. to make themselves more drought-resistant. If you wanted a fire as hot in the East you would have to spray the woods with fuel oil first and then set it on fire. ( I’m sure any Chapparalians will tell me if I am wrong about that).

” Windbreaks”? Really? The Santa Anna winds blow millions of glowing embers anywhere up to a mile away from the fire they pick them up from. Embers don’t care about “windbreaks”.

I have rather direct experience with the ineffective protection of “firebreaks” in wildfires.

My tract home in Santa Rosa, Calif burned down on the morning of October 9, 2017 in what is known as “The Tubbs Fire”.

There was a rather large firebreak in the path of the fire, that being US highway 101, with 6 concrete lanes + center divider.

Many firefighters had clustered in the K-Mart parking lot, believing the fire would not “jump” the 101 highway.

Well, a river of embers jumped the 101 and the K-mart roof started burning.

I watched my neighborhood start burning as embers were flying 50-60 feet in the air and dropping on the ground starting brush fires and apparently blowing into attic vents and starting homes on fire.

A co-worker in a more rural area miles further away later told me he had embers light small fires in his fields that he was able to put out.

Embers can travel a long distance in a wildfire.

The Western insurance model of all types, fire, flood, health, auto, life, was conceived as a clever way to accumulate cash for capital investments; thus, insurance companies of all types are essentially financial institutions. We have seen in health insurance how this scheme is fraught with corruption on the demanding end, while enriching the institutions and their managers as the top.

Social Security differs from pensions, which are another scheme to accumulate capital. SS is a ‘pay-go’ system where workers donate cash to care for retired and disabled workers. The fact that excess funds are invested in US Treasuries does not alter the philosophy as the declared intent is not to fund government debt, but provide security to workers.

There is much talk these days of Medicare For All, which would be similar to the pay-go of social security. The advantage is low administrative costs and universal access to healthcare. America could provide other forms of insurance in the same way. All that is lacking is the political will and overcoming entrenched interests of the rentiers.

I watched the Fire Industrial Complex in action here for the Coffee Pot Fire which started in August in Sequoia NP, where it was mostly a crisis=opportunity gig, with no structures or lives threatened on a lightning strike fire in an area that hadn’t burnt since the Grant administration.

They strung it out for a few months, doing backburns to keep it going in essence, and $60 million in cost later called it good.

The LA Infernos (note to the Lakers, dude there are no real lakes in LA, its a desert, man) are completely different, there is no way to pad that lily.