Before our current age of nuclear war anxiety, there was widespread concern about an earlier terrifying weapon of mass destruction: poison gas. I will describe the history of war gases in the context of our current concerns about atomic war. It is an ugly topic, but examining it may provide some hope for a way out of our current predicament.

How It Started

The origins of chemical weaponry trace back to antiquity, when armies first used noxious substances and smoke to gain an advantage in battle. In sieges, defenders and attackers alike employed burning sulfur, pitch, or quicklime to create choking or blinding clouds. The Byzantines’ famed Greek fire, developed in the 7th century, also had elements of psychological terror and chemical combustion, though it was more incendiary than toxic. These early efforts, however, were rudimentary and lacked scientific control.

It was not until the scientific advances of the late 18th and 19th centuries that the foundation for modern chemical warfare was established. Pioneering chemists such as Carl Wilhelm Scheele, Humphry Davy, and others isolated and described a variety of highly toxic gases, including chlorine, phosgene, and hydrogen cyanide. These substances were known for their suffocating and lethal properties, and some military thinkers began to consider their potential use. During the Crimean War in 1854, British scientist Lyon Playfair even proposed deploying shells filled with cacodyl cyanide against Russian forces, though the idea was rejected as contrary to the norms of civilized warfare.

The first systematic and large-scale use of chemical weapons came during the First World War. As the Western Front descended into stalemate, Germany turned to its growing chemical industry and the expertise of chemist Fritz Haber to develop a new weapon. On April 22, 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, German forces released over 150 tons of chlorine gas from cylinders, creating a greenish-yellow cloud that drifted across no-man’s-land into Allied trenches. The attack killed and wounded thousands and shocked the world. In the years that followed, both sides deployed an escalating array of agents, including phosgene and diphosgene, which were more potent choking agents, and finally mustard gas, introduced in 1917, which caused severe chemical burns and long-lasting contamination of the battlefield. By the end of the war, chemical weapons had inflicted more than a million casualties and left a lasting scar on the collective memory of the conflict.

On October 15, 1918, just weeks before the Armistice, Adolph Hitler was serving as a corporal in Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16. On that day, his unit near Ypres in Belgium came under a British mustard gas attack. Hitler reportedly suffered temporary blindness and lung irritation from exposure to the gas cloud. He was evacuated to a military hospital, where he was still recovering when Germany signed the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Hitler later described his hospitalization and the news of Germany’s surrender as one of the most traumatic experiences of his life, shaping his sense of betrayal and anger that would feed into his postwar political ideology.

Chemical Deterrence

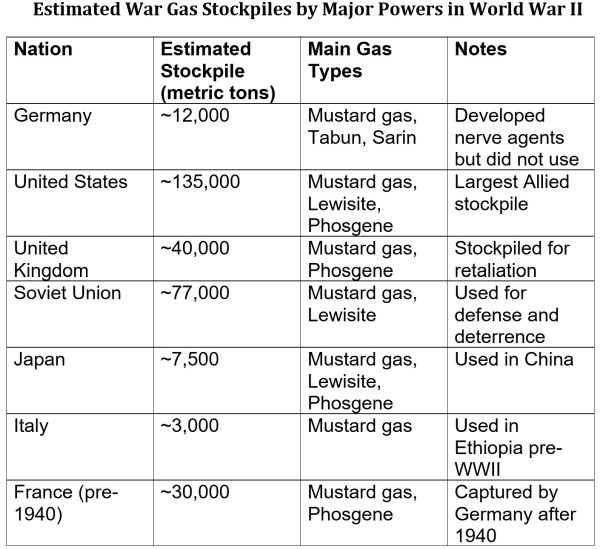

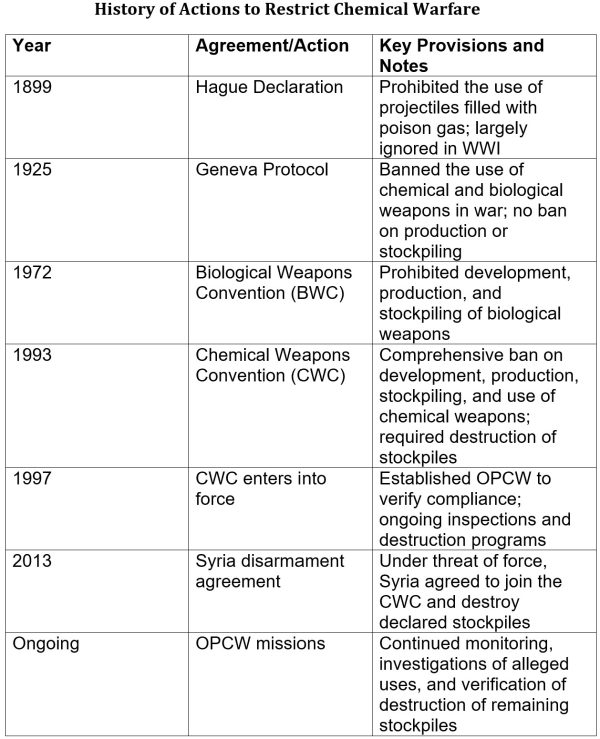

The interwar years saw widespread condemnation of chemical warfare and the signing of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which banned the use of chemical and biological weapons. Yet research continued in secret, with nations stockpiling mustard gas, phosgene, and newly discovered nerve agents such as Tabun and Sarin, developed in Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

Although WWII was vastly more destructive than WWI, war gases were not used in the European or Pacific Theaters. The reason was fear of retaliation. The allied and axis powers had amassed substantial stocks of chemical weapons that acted as deterrents. The exception to this standoff was Japanese use of war gases against Chinese military and civilian personnel from 1937 to 1945. China had no gas weapons with which to retaliate.

The history of chemical weapons reflects a tension between scientific progress, military innovation, and ethical restraint. What began as crude battlefield smoke evolved, through industrial and scientific advances, into some of the most feared weapons of modern war—spurring both horror and international efforts to control their use. Public revulsion and international diplomatic efforts eventually resulted in comprehensive treaties banning chemical weapons.

Final Agonies

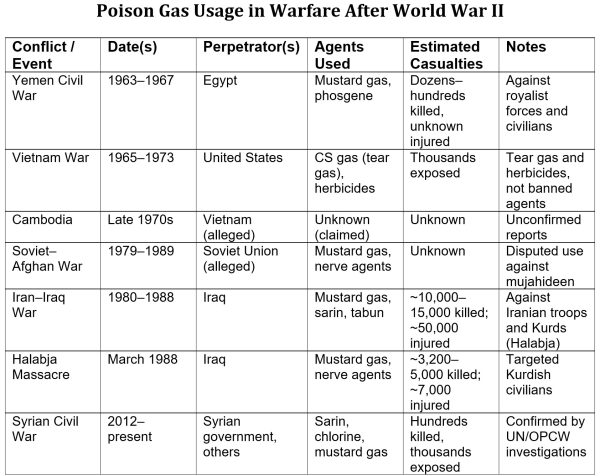

Poison gas use in warfare did not end completely after WWII, but major powers gradually abandoned such weapons because of deterrence, treaty restrictions, and operational limitations. Chemical weaponry was used sporadically in regional wars, but this was seldom acknowledged by the belligerents. The most extensive post-WWII use of poison gas was by Iraq in its war with Iran, but in no case was this weapon strategically decisive. The technology of weaponry increasingly favored precision targeting over area-effect munitions, and this further diminished the utility of an internationally banned weapon.

From Poison Gas to Radioactive Fallout

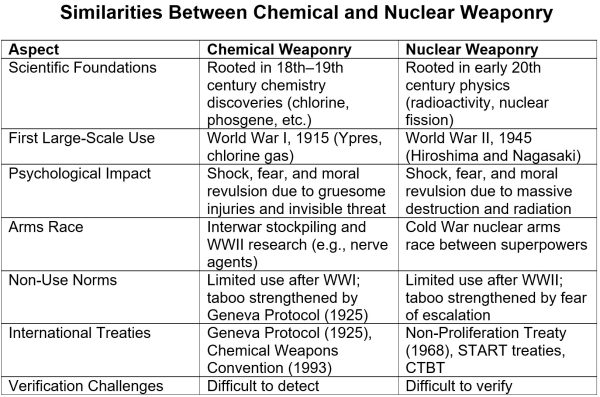

The evolution of nuclear weapons has followed a course parallel to that of chemical weapons. In the years following the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, nations have accumulated large arsenals of weapons that are so frightfully devastating that they have yet to be used. This balance of terror has been accompanied by diplomatic efforts to lessen the danger by limiting the size and composition of nuclear arsenals through arms control treaties.

The historical parallels extend to the lives of Fritz Haber and J. Robert Oppenheimer. Both were distinguished scientists, prominent in their fields, who turned their talents toward designing weaponry for patriotic reasons.

Haber, who was raised in a Jewish family, believed that his work in leading development of war gases in WWI would spare him from persecution under the Hitler regime, but he was effectively forced out of his prestigious position at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute and left Germany in 1933. Among his scientific achievements was receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1919 for the Haber process enabling the efficient generation of ammonia for fertilizer, which greatly expanded global food supplies. The dark legacy of this work on toxic gases was the research that would later result in the development by others of the Zyklon B gas used in the German extermination camps. Ironically, Haber died in 1934 while on his way to assume the directorship of what would become the Weizmann Institute in Palestine.

Oppenheimer left a distinguished career in physics to lead the Manhattan project, which developed the first atomic bomb. He was motivated by the fear that Nazi Germany would develop a nuclear weapon. When Germany was defeated, this threat no longer existed, but he was unwilling to oppose the use of the bomb against Japan. He subsequently felt moral unease and worked to prevent further use of nuclear weapons by advocating international agreements to prevent an arms race. He hoped to prevent further proliferation and to make nuclear weapons a political deterrent, not a military tool. His resistance to development of the even more devastating hydrogen bomb led to the government stripping him of his security clearance 1954. He was cast out of the inner circle of U.S. nuclear policy, publicly shamed, and made a symbol of the dangers of dissent during the Cold War.

Conclusion

If the future of nuclear weapons continues to parallel that of chemical weapons, we may hope that the current balance of terror will be ended by arms control agreements culminating in dismantling of nuclear arsenals. Although neither chemical nor nuclear weapons can be un-invented, their availability and the willingness to use them can be effectively restricted. Moreover, the steady advance in the potency of non-nuclear weapons promises to meet the defensive military security requirements of the world’s nations. The final irony may be that the quest for an ultimate weapon becomes self-extinguishing.

I understand the need for hope as well as the reasoning behind this post. Unfortunately, I remember the insanity of the Cold War, and I can compare our current leadership, which is not leadership when compared with the past, but men-children with delusions of adulthood. Despite the much better quality of our past leaders, the world almost ended, if only because insanity can have its own logic, and there are always fools and fanatics, people with little minds and missing souls.

Perhaps the remarkable thing about the Cold War is that the world didn’t end. And the above report explains why. Power is about being in control but the results of using nuclear can’t be controlled. Therefore they don’t serve the needs of the powerful except as a kind of bluff or “strategic ambiguity.” This is why the Iranians won’t give up their program and their enemies insist they must–insisting with all the non nuclear weapons they can muster.

And we may think Kennedy was better for not recklessly blowing up the world but he was a Cold Warrior like the rest of them. Things haven’t changed all that much.

The above summary of the earlier wmd was good. Thanks.

Two tidbits to this good summary:

1) The first substantial use of poison gas in WWI occurred in January 1915 already — by the Germans against the Russians during the first battle of Bolimow. Ypres was therefore not a first…

2) During WWII, although neither the Allies nor the European members of the Axis used poison gas weapons, they did sometimes deploy them close to the battlefield. Close enough to be badly hit when their own stocks of poison gas underwent an “unscheduled release” — as happened in Bari, when the Germans thoroughly bombed the harbour where an Allied military vessel full of mustard gas was docked. The Allied immediately covered up the disaster…

The worst part of the cover up is that the American commanders refused to tell the medical staff that there was mustard gas present. And they had no idea what was causing the injuries or what cures to use as a result.

Vast amounts of mustard gas was disposed of post-war by simply incinerating it in situ in RAF airfields. Its still a major problem when it comes to redeveloping the former airfields all over the UK.

A lot of phosphorous was produced in the Albright & Wilson fertilizer and match-making plant in west Birmingham (Oldbury), England – although it was never confirmed they made phosgene, much of the phosphorous produced was likely used for incendiaries. Vast amounts of waste material was disposed of in the area – a friend of mine who grew up there in the 1970’s said that it was a popular childrens game to throw the ‘phos-rock’ at each other when they played on the many spoil heaps in the area (often former collieries where various industrial wastes were dumped) – when it hit the ground it would spark up. It caused major issues for the foundation of the M5 motorway where it runs through the area (phosphorous and concrete are not a good mix). I don’t think they ever identified any phosgene dumping in the area, but there were plenty of rumours.

A huge amount of munitions were dumped between Dumfries and Northern Ireland in the Irish Sea. Apparently including chemical weapons.

Poison gas must be the most disappointingly unsuccessful technology ever deployed in warfare. It’s too dependent on wind direction and atmospheric conditions, and too easy to develop countermeasures. Its real use is as a shock weapon against unprepared or unsuspecting opponents, and of course civilian populations, to create panic. In WW1 the Mk1 urine-soaked handkerchief was used as a protection almost immediately, and once gas attacks were anticipated, they could be prepared against. Gas was seldom decisive above the tactical level.

If WW3 had ever been fought, Europe would have been buried under a cloud of poison gas: the Red Army had extensive CW capabilities, and had developed weapons that were less affected by wind and weather because they could be dispersed as droplets giving off poison fumes. But even then, doctrinal works at the time show that CW was only ever seen as a harassment weapon: the idea was to make NATO troops suit up, to reduce their mobility and to exhaust them. But they weren’t expected to be very lethal in themselves. All in all, CW has been a bit of a dud as a weapon.Thankfully.

I was just going to poat similar. As part of a combined arms approach like the Soviets planned, they may have had some effect. But like most “war winning miracle weapons” throughout war, they never quite loved up to the hype.

If they had been used on mass against civilian cities it may have been different, but thankfully they were not.

One interesting part about the Soviets is that they did a lot of live training with chemical weapons. So they had a fairly good understanding of how weapons would react in a war. Along with a few dead every year.

> they never quite loved up to the hype.

What a wonderful typo. :-)

Always the Russians, huh? The US was actively working on CW during the cold war:

Dugway sheep incident

Do we also need reminders of the anthrax incident at Ft Detrick after 9/11?

No doubt evil scientists continue such work here and abroad.

Well, at the end of the Cold War USA had 30,000 tons of usable chemical weapons and Soviet Union had 33,000 tons.

Oddly enough, a CIA SNIE from 1984 claims that Soviet Union had several times more CW than USA and at the same time states that from the 1960’s Soviet Union was not going to use CW first, if at all, and that the Red Army doctrine and training reflected this fact since the 1970’s. The estimate is that Soviet Union would use CW only as a preparation for a nuclear strike.

The SNIE admits that it’s estimates are a complete departure from the previous estimates, so this sort of dates Aurelien’s time in NATO circles and exposure to information perhaps not honestly reflecting the actual state of affairs.

Well, NATO forces trained extensively against CW use by the WP at the time, but not at all in its use. The US stockpile remained in place, as I dimly recall, as much as anything else because of the cost and complexity of its destruction. In any event, CW is only really of any value as an offensive weapon, to disrupt the defenders and enable you to advance more quickly. To the best of my knowledge it has never been used defensively, and it’s hard to see how it could be. It suited the WP concept of operational/tactical offence, and their troops were equipped and trained to operate in a CW environment. If I remember correctly, even aircraft were equipped with spray tanks.

Strategically, of course, the WP orientation was described as defensive, and exercises usually began with a token NATO attack, for political reasons. In such a scenario it may well be that offensive CW use was also taken for granted and this is what the CIA was reporting on. NATO had no such capabilities, but such was the level of ignorance and distrust between the two sides that the Soviet Union might well have thought it did.

In the Great War, the most effective use of CW, overall, was on the tactical defensive–the employment of high-persistance blistering agents (mustard gas and its variants) to deny ground, or for counter-battery harrassment. This type of CW was advantageous to Germany when on the defense, in well-prepared positions, during most of 1917.

Of course, on the strategic offensive, there will be many situations in which “denying” certain areas of ground is part of the attack plan. But generally, in mobile operations, you wouldn’t want to contaminate areas which you want to capture, or through which you want to advance.

It’s always the Russians, and Agent Orange never existed.

That wasn’t a sly reference to Trump by any chance, was it?

I recall Tukhachevsky used poison gas on peasant rebels at the end of the civil war. It was an abject failure due largely to wind (I don’t think it killed anyone in the end, certainly not the rebels). I suppose we learned from that early experience.

Nice summary.

Will the next terrifying “advance” in warfare be the exponential increase in the use of drones and other AI-based machine-on-human conflict? If not yet considered weapons of mass destruction that day may come. Stay tuned.

I have a suspicion that drones have had there major impact and that will reduce now. They will remain an important weapon, a very important one, but like tanks they will not win a war on their own. Already effective low tech countermeasures have been developed. Rapid fire anti-aircraft guns, mesh protection screens, etc. And what is going to be seen is a massive expansion in electronic countermeasures against them.

It’s always interesting how nations draw lines between chemical weapons and incendiary devices. I’m talking about white phosphorous a/k/a Willy Pete which has been used by every actor in every war starting with WWI.

The U.S. used it in Viet Nam and in Fallujah, Iraq. From one report: “In November 2004, during the Second Battle of Fallujah, Washington Post reporters embedded with Task Force 2-2, Regimental Combat Team 7 stated that they witnessed artillery guns firing white phosphorus projectiles, which “create a screen of fire that cannot be extinguished with water. Insurgents reported being attacked with a substance that melted their skin, a reaction consistent with white phosphorous burns.”[12] The same article also reported, “The corpses of the mujaheddin which we received were burned, and some corpses were melted.”[

Of course, Willy Pete isn’t illegal if it’s used to create a smoke screen and illuminate an enemy. It is absolutely illegal to use on civilians. Since the U.S. Army in Iraq had a difficult time determining who was a jihadist and who was a civilian it’s safe to assume that it was used against civilians.

Currently Israel is accused of using white phosphorous in Gaza.

I find it curious that an incendiary weapon that can “melt bodies” isn’t considered as dangerous as CW. Perhaps it’s just a case of humans rationalizing.

The smell of napalm in the morning, and phosphorous in the evening. Smells like . . . victory?

And right after the Battle of Fallujah, American bulldozers were seen scraping up the dirt in that city to be buried elsewhere so as to hide the evidence of what they had done. But there are still images of insurgents dead of WP to be found. It’s ugly stuff and is actually illegal under international law as it is the use of chemical warfare but ‘It’s OK when we do it.’

As for that chart showing poison gas usage after WW2, you can remove that whole entry of the Syrians using poison gas as “confirmed” by the UN/OPCW as a western-back and Jihadist propaganda op. It was disgusting and insulting. Chemical bombs that crashed through roofs but were stopped in their fall by a bed mattress, Jihadists in almost bare feet standing in a shallow crater to collect “chemical” samples, a CNN report sniffing a school bag “impregnated” with deadly chemical who confirmed those chemicals instead of, you know, dying. And OPCW was totally western-compromised by then so that the reports they released said the opposite of what their actual inspectors said. The whole thing was risible.

From above, from the if-the-shoe-fits department.

The exception to this standoff was Japanese use of war gases against Chinese military and civilian personnel from 1937 to 1945. China had no gas weapons with which to retaliate.

There was that bombing of Bari, where, in 1943, I think, Germans launched a surprise bombing attack that wrecked a bunch of cargo ships loaded with supplies for the Allied armies in Italy, including one, as it turns out, was carrying mustard gas…

Oh, I see that vao pounted to this already.

Wasn’t the exorbitant cost of caring for gassed WW1 vets a determining factor in their ban?

As far as I know, the claims of poison gas used in Afghanistan and Cambodia were fairly crude Cold War propaganda.

Current anti-riot gases would probably have been categorised as poison gases under the Hague Convention.

The most important use for poison gas in warfare, apart from terrorism against civilians, is in forcing soldiers to wear cumbersome equipment; full protection against blister gases or nerve gases is extremely heavy and very hot to wear, making movement difficult. However, the rise of remote-controlled mobile weaponry probably acts against that to some extent.

A great summary!

Regarding the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Civil war: I thought the use of chemical weapons was never confirmed and the alleged attack was a propaganda fabrication by the US and its allies. Correct me if I am wrong!

In the first year or so of the WW2, troops and public are often shown with gas masks in photos, and it was standard gear in all armies and yet not one was ever needed.

In the UK alone, 38 million gas masks were issued to the army and public in the lead up and during WW2, what happened to ’em all?

Since I don’t see Otto Hahn mentioned:

Later Nobel laureate Otto Hahn (for discovery of fission 1945) was involved in the testing of poison gas. There is no proof that he actually was involved in the development or the idea. He admitted his involvement in his autobiography in 1968. This is important to point out since to this day Hahn is regarded a benign example of an outstanding scientist who retained integrity and all kinds of public places and institutions have been named after him.

I believe his grandson Dietrich Hahn was intent to keep it this way with a rather strict way of providing records on his grandfather. Dietrich Hahn, *1946, moved to Thailand around 2012. There is rumour that he died there in 2024.

The major scientifc work on poison gas in Germany was done by Hahn´s boss Fritz Haber as described above.

Haber had formed the poison gas unit of the German Army and Hahn was member of that. Just like James Franck, Gustav Hertz, Wilhelm Westphal, Erwin Madelung and Hans Geiger.

Haber was director at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut, one of the major German institutions for R&D which also formed one backbone for scientific expertise of the Third Reich and war prep.

Haber´s wife was Clara Immerwahr herself an eminent chemist. She killed herself in 1915. Today it is said due to her shock over her husband´s work on poison gas, the unhappy marriage and Haber´s affair(s).

Of course, in case people didn’t know, Haber was Jewish and he was exiled from Germany after Nazis took over–might have been self imposed, as he could have been thought to be too important even by the Nazis.

I had read that he died in Switzerland when he was supposed to become the head of a new lab in Palestine. I used to think that was just sad, but current events make me think of much darker implications had he actually gone to that lab, whatever that was “officially” supposed to be…

I think depleted uranium munitions should also considered be chemical weapons. Also, I believe Aaron Mate might have something to say about attributing the Syrian sarin to the Syrian Government. I dare say the evidence of any CW use is sketchy, and is likely a fabricated false flag responding predictably enough to Obama’s ‘Red Line’.

Didn´t OPCW 1,5 years ago officially confirm Hersh´s report from 2014?🤔

Of course almost unreported.