Let’s talk about money, specifically the use of bribery as a weapon in war and geopolitics. Like any weapon, it has technical characteristics and operational effects. In the ancient world bribery was practiced openly in the form of tribute paid by subject states to dominant powers. Masters were bribed to “protect” their subjects. In the modern era, bribery is legally discouraged and notionally repudiated by all, yet it persists as a significant factor in the conduct of armed conflicts and geopolitical struggles. Although international bribery of military and political figures is clandestine, a great deal can be deduced from occasional disclosures of these practices. When making a case for a crime, lawyers frequently assemble evidence for means, motive, and opportunity, so I will follow that model in this discussion. Although I will focus on U.S. government practices in this discussion, other major countries act in a similar, if more limited, manner.

The Means of Government Bribery

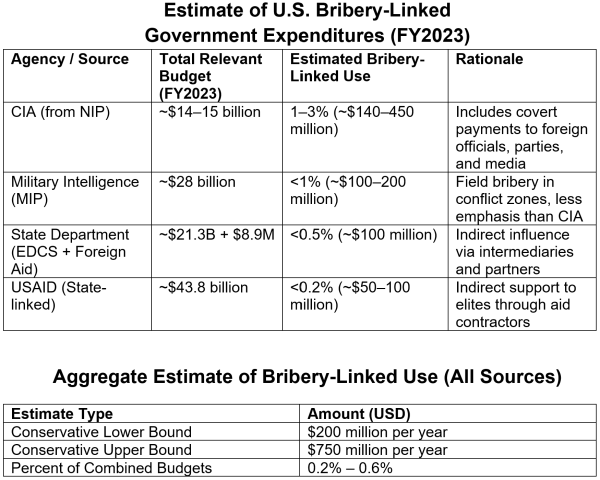

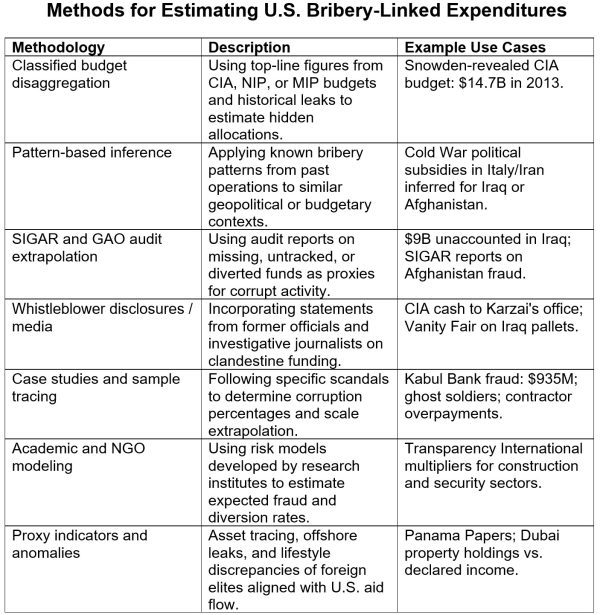

The U.S. has considerable resources available for bribery. The black budgets of the U.S. intelligence agencies and discretionary funds of the State Department amount to many billions of dollars. Even a small fraction of this amount can fund a massive amount of international bribery. Analysts have developed a number of tools for estimating the scope of this clandestine activity.

The Motives for Government Bribery

The benefits of bribing foreign officials include securing markets for U.S. corporations, establishing military bases, obtaining intelligence information, and preventing other nations from receiving more favorable treatment than the U.S. If there is a potential for armed conflict, it is usually cheaper for the U.S. to bribe than to fight, but if armed force is applied, bribery increases the chances of victory, as it did in the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Another cost-effective form of military bribery is the funding of proxies, such as the overthrow of the Assad regime in Syria by operation Timber Sycamore. There are many desperate young men willing to take up arms for pay, and the loyalties of their leaders are often for sale. Of course, once a proxy war reaches a sufficiently large scale, covert financing is no longer feasible, and the U.S. provides direct aid to “allies.”

The Opportunities for Government Bribery

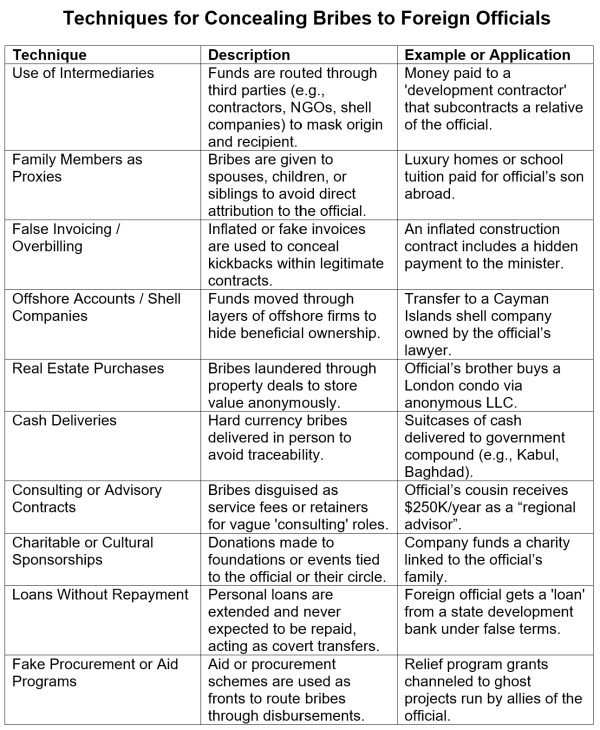

The opportunities for bribery of foreign officials are provided through the elaborate and effective financial techniques by which large bribes can be delivered secretly. The U.S. government relies on the same methods that wealthy individuals and criminals use to conceal the sources and destinations of large cash transactions. These methods involve cutouts, shell companies, multiple offshore bank transfers, and many other techniques that make investigation and discovery of the bribes nearly impossible

.

.

Although Congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence agencies notionally requires disclosure of bribery transactions, the information provided to Congress generally does not include identification of the parties participating in the bribery process. Thus the U.S. government maintains secret ties to many individuals and institutions whose purpose is to facilitate clandestine bribery. Once one grasps the considerable scale of U.S. bribery of foreign officials, many puzzling events in international relations start to make sense.

Clandestine bribery functions not as a rogue tactic but as a systemically embedded instrument of U.S. foreign policy, enabled by legal ambiguity, institutional compartmentalization, and perceived strategic necessity. Though individual payments may be small in scale, their cumulative effect is substantial: reshaping political outcomes, sustaining alliances, and projecting influence beneath the threshold of official diplomacy. Accordingly, bribery should be suspected in cases where foreign officials exhibit unusual decision-making, such as abrupt reversals of longstanding positions, unexplained shifts in policy alignment, or the initiation of unexpected diplomatic or military initiatives that lack clear domestic justification.

Curious Cases Suggesting Bribery

- The Philippines’ recent antagonistic posture toward China, its largest trading partner. This stance includes: – Granting expanded basing rights to the U.S. – Publicly challenging Chinese maritime claims – Reorienting military procurement toward Western suppliers. Such a pivot, particularly in the face of substantial economic costs, raises the possibility that covert inducements were involved.

- Eastern European Alignment with U.S. Defense Policy: The accelerated shift by certain Eastern European states to host advanced U.S. military installations—despite domestic political divisions and economic dependence on regional neighbors—suggests the possibility of inducements to override internal resistance.

- Overnight Policy Reversals in West Africa: Sudden terminations of Chinese infrastructure contracts in favor of U.S.-backed development alternatives, particularly in politically unstable or economically distressed nations, raise questions about the presence of behind-the-scenes financial incentives.

- Support for Controversial UN Resolutions: Instances where small or economically vulnerable countries reverse longstanding non-alignment stances to support controversial U.S. positions in international forums (e.g., votes on sanctions or recognition issues) may reflect the influence of off-the-record payments or promised aid.

- Surprise Recognition of Diplomatic Allies: Nations that unexpectedly sever ties with traditional economic partners to recognize U.S.-backed governments or territorial claims (e.g., Taiwan over China) without public consultation may be acting under covert inducement.

These examples are not presented as proven cases of bribery, but as pattern-consistent anomalies in foreign policy behavior that, when viewed through the lens of established clandestine funding practices, merit close scrutiny.

Conclusion

There is abundant evidence that the U.S. government has institutionalized practices of bribery of foreign military and political officials. Thus bribery, explicit or indirect, is a plausible explanation for unexpected decisions of foreign leaders favorable to the U.S. but contrary to the interests of their nations. The U.S. Congress should act to restrain this activity because of its potential to undermine Constitutional war powers and trigger undeclared wars. Intelligence agency disclosures to Congress should fully describe the means by which bribery is effected. Utilizing bribery, a fundamentally corrupt practice, in “defense” of U.S. national security undermines the international reputation of the United States and betrays the trust of citizens in their government. The money weapon is a poor choice for inclusion in an arsenal of democracy.

I know this may be prejudiced, but I don’t believe Mossad is as capable as its reputation suggests. I believe their intelligence operations depend almost entirely on bribery and intimidation.

Israeli intel agencies earned their reputation mostly on “James Bond” type operations–daring, cinemaseque, but downright counteractive to good “spying.” Even then, one has to imagine its ability today has to be a shadow of its former self–the old Mizrahim, once known as “Arab Jews,” who could seamlessly infiltrate their former homelands, are now mostly gone, replaced by their Hebracized descendants who know nothing of the Arab and other Middle Eastern worlds. This does not make for a good basis for sound intel operations, I think.

I just realized that this has a weird analogue in 30s and 40s. Germany from 1920s onward was full of Russian emigres, many of whom were actually German, whose ancestors had served the Russian Empire for generations or even centuries. Yet, despite their presence, German intel on USSR was dreadful, although they did form the core of the Brandenburgers, the German special ops, who were apparently very good early on during Barbarossa, until German realized special forces are overrated and made them into regular troops…

I’m far more interested in what are charmingly called “campaign contributions” domestically. This is “legalized” bribery and should be treated as criminal behavior requiring both the bribe contributor and the recipient to get prison time. Dark money and clandestine advocacy groups are a form of bribery as well. We hear over and over again about what “the donors” want and what I want for them is a dank dungeon cell.

This government will never punish such crimes but perhaps a future one will. All campaigning should be limited, federally funded and usage of broadcast/cable time mandated under law as the price of being able to advertise in this country, not otherwise paid for. Billionaires/oligarchs should be forbidden from using personal funds to campaign for office.

Well said

It ought to be one person one vote, not one $ or one £ …

I suppose that you could consider the recent Trump/EU deal as a massive bribe writ large. Trump was dictating terms and crushing an ally – or so he thought – but the flip side is that the EU elite were ensuring that Trump and the US got even more involved with the EU rather than abandon them. And if the ordinary people of Europe have their lives immiserated, their pensions cut, their infrastructure fall down through lack of investment, well, none of that effects those EU elites does it?

Sorry if this is a bit too associative in relation….

On the particular case of Germany see this machine-translation from a book review on a 2019 study by historian Ivo Engels.

book title: “Alles nur gekauft?. Korruption in der Bundesrepublik seit 1949” / (“All is bought? – Corruption in the Federal Republic of Germany since 1949”), 2019

This is establishment scholarship, so the criticism is not as much in the open but it says enough to understand the described nature of “corruption” in post-war Germany as part of the “structure”.

So it falls short of your point obviously but it is important that academia produces at least such work.

From my limited studies post-academia years I would assume that research on such topics has decreased after a high between the 1960s and 1990s when left and far-left scholars used their positions to unearth data and put it into a context that was hardly publishable in mass media. Today this area of expertise has been transferred to the NGO-pseudo-educational-space that is not questioning theories and probing findings but is only interested to prove pre-supposed views in order to close discourse instead of opening it up. It is not scholarly but political in function and by legimitacy.

“(…)

There is no such thing as “corruption,” and what is understood by it is defined (to a certain extent) by discourse, which also determines the boundary between public and private, between legitimate and illegitimate actions. Engels even goes so far as to deny the topic of corruption any suitability as a scientific category, arguing that it is a moral judgment that can be described but not measured. The book’s focus on public debates also arises from the fact that it deals with a phenomenon that is not easy to address because it usually occurs in secret, with the goal of remaining hidden.

Engels’s finding that corruption played a comparatively minor role in the early Federal Republic does not mean that it did not exist. Instead, the book clearly demonstrates how the political and media elites of the Adenauer era agreed that excessive focus on, or even scandalization of, corruption cases would endanger the young democracy and reactivate anti-democratic sentiments. Instead, the young Federal Republic achieved a discursive coup: corruption was interpreted as a key characteristic of totalitarian regimes, and parliamentary democracy was no longer viewed as a hotbed of corruption, as it had been in the Weimar era, but rather prescribed as an antidote to it. The restrained manner in which corruption cases were discussed (or not discussed) in the media in the early Federal Republic, which Engels somewhat euphemistically described as “objective,” therefore had much to do with the West Germans’ struggle to distance themselves from the Nazi regime and simultaneously build a new democracy. To support this, the media and politicians created an image of a supposedly corruption-free Federal Republic. This was not shaken even by (…) major scandals

(…)

The focus here is less on corruption itself than on the associated social concepts of politics, economics, and morality, private, economic, and public benefit.

(…)

One of the most insightful and controversial passages in the book is the lengthy excursus on the emergence of a neoliberal-inspired anti-corruption policy in the 1990s, a “decade of corruption obsession” (p. 170). Academics, businesses, governments, and international organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and Transparency International placed the issue of corruption on the international agenda and declared war on this “cancer” (World Bank President Wolfensohn). They thus became actors in a globally developing “anti-corruption industry” (Steven Sampson).

(…)

Corruption became evidence of negative state influences, a political instrument for implementing political and economic reforms, and an “explanation for the failure of the market economy in transition countries” (p. 199): It was not the market that was to blame, but the corruption of state elites.

Engels is just as critical of the neoliberal anti-corruption policy as he is of its scientific foundations, in particular of an economic corruption research characterized by “naivety” (p. 153), which turns perceptions into facts, turning correlations into causalities and ideological assumptions into seemingly proven connections between the market, the state, and corruption. Paradoxically, according to Engels, this deceptive quantification also went hand in hand with a moralization of corruption under the banner of transparency(…)”

I just knew we shouldn’t have taken the unlimited mileage option on our rental Karzai.

I think this is underestimated. How much did the CIA make on Heroin during Vietnam, Crack Cocaine to LA and beyond in the 80’s early 90’s, Opium fields in Afghanistan for 20 years and probably ongoing. Further, MNC’s bribe maybe more. Whatever happened to the BAE bribery case?

Adding, that $9 billion on pallets in Iraq is dwarfed by the electronically transmitted funds to Swiss and other banks * probably 30x.

It’s sleight of hand … look over Here.

Still maddening though!

A very informative and thought provoking article, Haig. What bodies put together the sources for the estimates?

Here are some of the investigators:

Transparency International

U.S. Department of Justice (FCPA Unit)

OECD Working Group on Bribery

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO)

World Bank Integrity Vice Presidency (INT)

European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO)

Global Witness

Many, many thanks.

OMG! Does this mean that Hunter Biden’s pay ($1 million annually) as a board member for the Ukrainian gas company, Burisma, was really a ‘bribe?’ I mean, it was pure coincidence that his dad was US President at the time, yeah?

Your article, Haig, read following Matt Stoller’s latest piece, ‘Armed Madness,’ about how the anti-trust division is being turned into a ‘pay-to-play’ operation, has ruined my day. Nay, my entire week. What could go wrong with one big freight line monopolizing the US rail transport system? Or ending export controls on high-tech products? Or shaking down Ivy universities, Meta and Disney, and big law forms for millions in tribute? Or putting the big money behind building ginormous data centers in support of AI. Which, BTW, doesn’t go on strike or ask for pay raises. Yet …. Dave.

I considered citing Hunter Biden’s boasts about his family’s perfected techniques for money laundering, but I assumed this would be old news for the NC regulars. The congressional inquiries into the Biden finances revealed the multiple shell companies that are a typical sign of funds transfer concealment. Joe Biden explained some of the money received as repayment of undocumented “loans” to relatives. The Bidens have left, but the bad odor lingers.

Big bad wolf telling Nato members that 5% is an adequate “contribution” to this years hunger games cannot be more close to Caesar and co?

I mean, it sounds a lot more like more recent denizens of the same peninsula.

Bill Black and Michael Hudson on Corruption in Finance

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2023/06/bill-black-and-michael-hudson-on-corruption-in-finance.html

Patrick Lovell, Bill Black, Michael Hudson

This was my favorite part, amazing to me. I still need to go through the rest more slowly (and the article above!).