Yves here. VoxEU regularly posts on studies that mine historical data, and here I mean of long ago history, either to draw lessons for today or to show that seemingly “so-old-how-can-it-still-matter” events still cast a shadow. This analysis is of a shift towards more representation in the medieval era, as in what is commonly thought of as rule by nobles. It finds that increases in wars lead to increases in representation on local councils, which in a longer time frame, meant an acceleration of the trend of medieval constitutionalism.

So in this time of generally dispiriting news, there may be a small silver lining. The ferocious drive towards the rearmament of Europe may require a big reduction in its democratic deficit to get done….or won’t get done much at all due to the need for at least some level of voter buy-in.

By Sascha O. Becker, Xiaokai Yang Chair of Business and Economics Monash University and Full-time Professor of Economics University Of Warwick; Andreas Ferrara, Assistant Professor of Economics University of Pittsburgh; Eric Melander Assistant Professor of Economics University Of Birmingham; and Luigi Pascali, Associate Professor Associate Professor Pompeu Fabra University and Kenen Fellow in the Department of Economics Princeton University. Originally published at VoxEU

In the grand sweep of history over the last millennium, political divergence between Europe and contemporaneous world civilisations preceded economic divergence. This column describes how the development of the institutional frameworks of medieval constitutionalism – characterised by representative assemblies, rule of law, and substantial fiscal and spending capacity – in European towns and cities paved the way for Western modern states. In a current international climate where democratic institutions increasingly appear to be on the back foot, history offers a sobering perspective on the hard-fought moves towards greater representation.

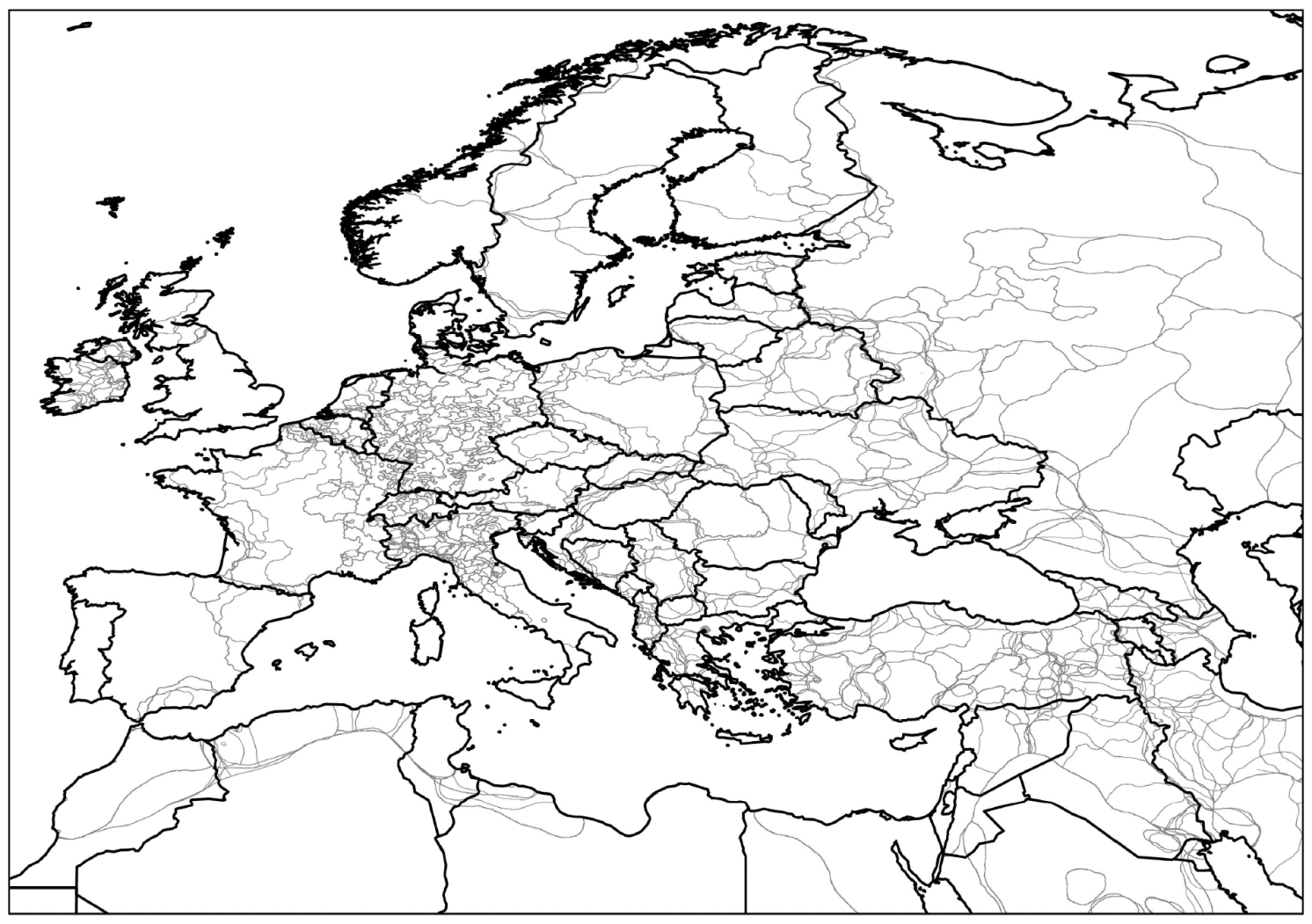

Europe in the Middle Ages was a place marred by near-ceaseless conflict between myriad weak rulers, particularly in a strip of land ranging from the Flemish and Dutch coast, via the German lands, to Northern Italy. Figure 1, which plots the territorial boundaries of European polities between 1290 and 1710, demonstrates the sheer density of borders in this region of Central Europe. Yet it was in this same region that the institutional package of medieval constitutionalism emerged, in towns and cities that enforced the rule of law, granted its citizens political representation, and developed increasingly sophisticated fiscal machineries.

Figure 1 De facto territorial boundaries in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, 1290-1710

Note: De facto territorial boundaries in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, 1290–1710. De facto territorial boundaries from the Centennia Historical Atlas (Clockwork Mapping 2018) overlapped at decadal intervals for the period 1290–1710 (light grey). Modern state boundaries also shown (black).

It has long been hypothesised that this “vortex of near-permanent war … forced [rulers] to strike deals that meant sharing political power” (Hoffman and Norberg 1994). But so far it has been difficult to empirically tease out the direction of causation. In the words of Stasavage (2016): “the evidence suggests some causal link between warfare and representative institutions, although we do not know in which direction causality runs.” Our recent paper (Becker et al. 2025) is the first in this context to present systematic evidence in favour of one direction of causality, from wars to representation.

New Data and Novel Evidence on War and Representation

Our work is underpinned by a massive effort to mobilise detailed data on German towns and cities for over five centuries that span the period of medieval constitutionalism. Drawing on the Deutsches Städtebuch (Keyser 1939-1974), a multi-volume encyclopaedia of German cities, we create a panel dataset documenting the conflicts in which cities were involved, characteristics of their councils, and the sophistication of their tax systems.

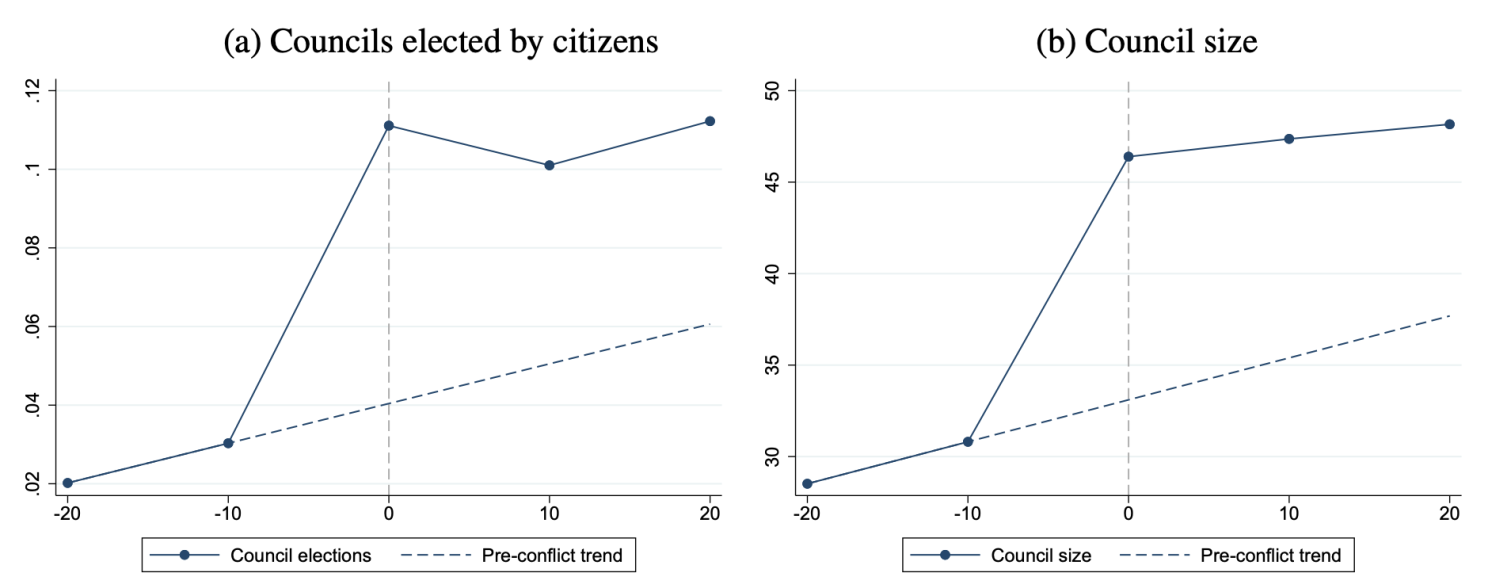

With these data in hand, we first document that exposure to conflicts appears to be related to the expansion of city councils (with more members indicating representation of wider strata of the population). Following conflict, these councils are also increasingly likely to be elected by citizens without the interference of the local lord. Figure 2 shows this result descriptively using the first conflict to which territories in our sample are exposed and tracking the evolution of council elections and sizes before and after the ‘event’.

Figure 2 Territory-level event study

Note: Evolution of political outcomes for territories before and after the first conflict to which they are exposed. The probability of citizens electing their local city council equals 1 if citizens can hold such elections without the interference of the local ruler. Council size is the number of members on the city council.

Succession Disputes as a Source of Random Variation in Conflict

To isolate variation in conflict exposure that mimics a randomised experiment, we introduce a second dataset to construct an instrumental variable for conflict. Using data on European noble families compiled by the ambitious Peerage project, we reconstruct the aristocratic network at each point in time and identify central individuals within this network. These nobles were key to war and peace in this period, and we home in on one aspect in particular: succession.

In the German context, a large number of conflicts were succession wars, fought over women’s right to inherit as rulers. By identifying the gender of important nobles’ firstborn children, we construct our instrument for conflict. The logic is the following: upon having their first child, nobles enter into a lottery in which either realisation (a male or a female child) is equally likely. But firstborn girls open up the possibility of challenges to succession and, hence, succession wars. The lottery thereby randomises some observations in our dataset into higher conflict proneness than others. It is this exogenous variation in conflict that we then exploit to identify the causal effect of conflict on political and fiscal institutions.

The War of the Succession of Landshut (1503-1505) illustrates how succession wars led to the rise and spread of medieval constitutionalism. Duke George of Bavaria-Landshut did not have a male heir, and named his firstborn daughter, Elisabeth, as his successor. This breached an agreement with the House of Wittelsbach, according to which Duke Albert of Bavaria-Munich would have been the legal successor. Albert refused to concede, and a destructive war ensued.

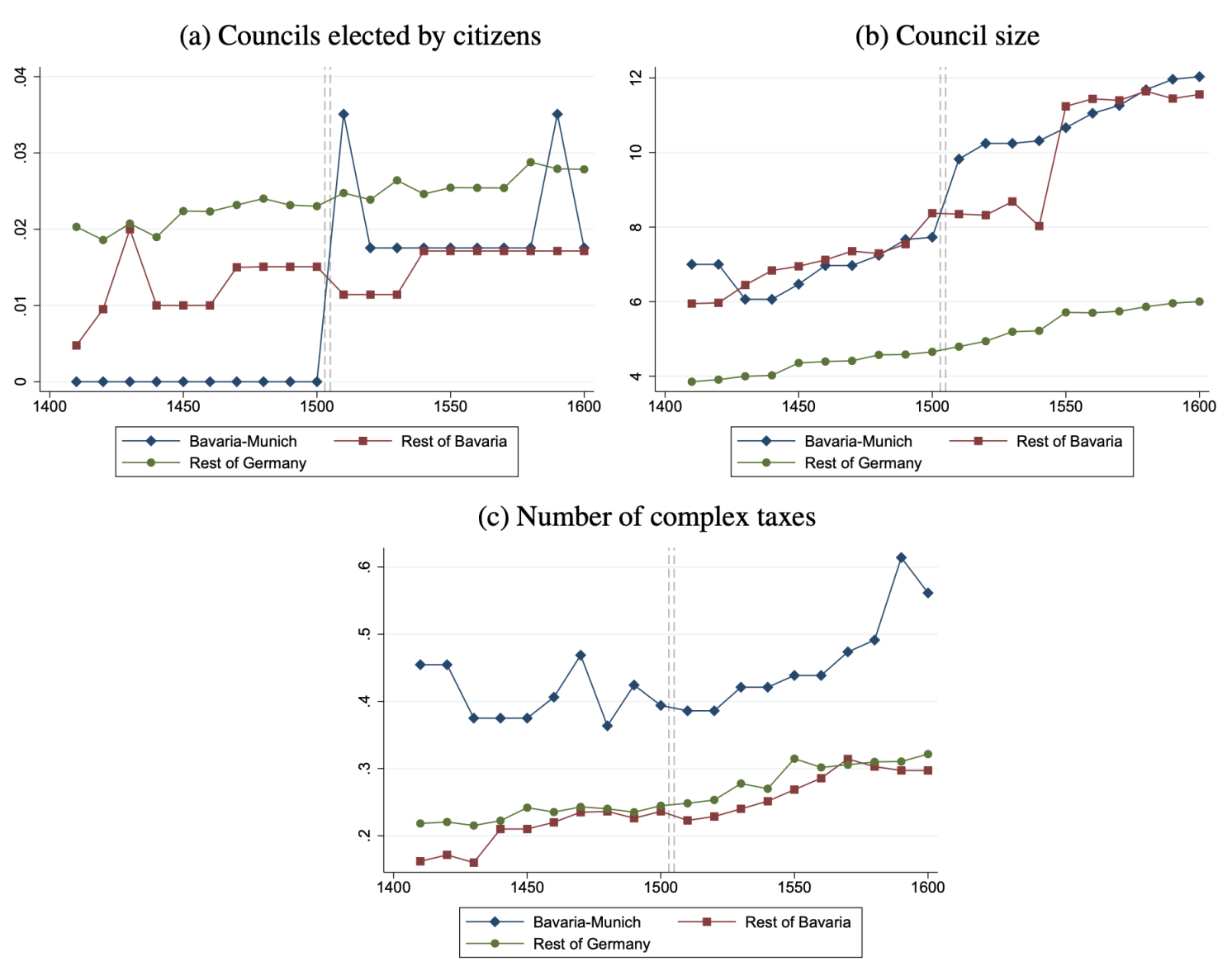

In Figure 3, we plot the evolution of political and fiscal institutions around the outbreak of the war of succession, comparing outcomes for Bavaria-Munich to those for the rest of Bavaria and other German regions. Cities in Bavaria-Munich saw an immediate increase in the probability that citizens elected their city councils and in their size. A few decades after the conflict, these cities had developed increasingly sophisticated tax systems, consistent with temporary war taxes evolving into more far-reaching fiscal capacity, based on income and wealth taxes.

Figure 3 Territory case study: Bavaria-Munich and the Landshut Succession War

Note: Evolution of political and taxation outcomes for cities in the territory of Bavaria-Munich, other cities in Bavaria and other cities in the German lands in the century before and after the Landshut Succession War (indicated with vertical dashed lines). The probability of citizens electing their local city council equals 1 if citizens can hold such elections without the interference of the local ruler. Council size is the number of members on the city council. Complex taxes refer to those taxes that require a register or administrative infrastructure to levy them because the taxed items are not easily observed, which includes income, wealth, or business taxes.

We then go on to confirm our findings from this single example in our full sample of cities and time periods. On average, after a war triggered by the birth of a female firstborn, cities see a 2-3 percentage point increase in the probability that their councils are elected by citizens and an expansion of the council by approximately two members. This is followed in subsequent decades by a shift towards more sophisticated forms of taxation.

Long-Term Implications of Medieval Constitutionalism

In the final section of the paper, we investigate the long shadow that the institutional package of representation and high fiscal capacity – developed in the context of medieval constitutionalism – had on the subsequent rise of modern states. Previous work highlights the importance of high tax capacity in state formation (Tilly 1975, Gennaioli and Voth 2015) and a recent paper by Cantoni et al. (2024) documents empirically the importance of centralised territorial fiscal systems in the early modern era. Our exercise here complements these findings by highlighting the parallel importance of city-level tax systems until at least 1700.

We show that the cities and territories in our sample that developed high fiscal capacity in the context of medieval constitutionalism were more likely to come out on top in the process of territorial consolidation from the 17th century. Concretely, we look at instances where cities switch hands from one territory to another, and calculate the difference in tax capacity between the gaining and losing territory. From the year 1600 onwards, there is a pronounced increase in the tax advantage of conquerors over the conquered.

Conclusions

All told, our findings underscore the role played by wars in the emergence of crucial elements of the blueprints for modern states. In particular, we re-emphasise – now equipped with systematic causal evidence – conclusions from previous qualitative and historical literatures that the development of representative institutions was not a foregone conclusion, but rather a silver lining of the bargain that conflict forced rulers to strike with their subjects.

See original post for references

The Ukraine War may be bringing the EU closer to fiscal union.

Representation for whom? The wars of Europe in the Middle Ages indebted the the kings, and so the states, who depended upon tax revenue. They squeezed and squeezed; there were peasant revolts throughout the period, such as Watt Tyler’s rebellion in England in 1381, right in the middle of the Hundred Year’s War, and the Peasants’ War in the German states. The wars didn’t stop, and the enclosures of the commons continued. The peasantry’s resistance to their conditions represented some constraint on kings to do whatever they liked, but the representation that was gained was mainly and effectively gained by the ascendant merchant and money-lending classes, in whose grasp it has remained, for the most part, exclusive. While the peasantry supplied the food crops and surplus to export, as well as fresh bodies for king’s wars of choice, the merchants provided the imports and inputs for more and more advanced war-making, and the money-lenders supplied the financing. The privatizations of Church property during the period could also be seen as economies, austerity measures taken by kings interested in financing adventurism.

I’m not sure what, if any, implications this historical reporting carries for us today. To study the period with the context and detail required for assessing its relevance to social conditions in our time, we’d have to look at it in light of the social conditions of that period, and which classes, generally, benefitted from the constitutions and other trappings of the modern state.

I’ve been working with “AI” lately under the orders of my evil corporate masters, and I would postulate that something that it might do well is to ingest vast amounts of texts to help researchers come to conclusions about how people actually behaved in the past.

While period literature is our most reliable window for this, but I would think that (from what I’ve seen), adding title registries and all sorts of obscure public records (I know that Medieval Italy was very good at this) to an LLM library would reveal insights.

Sure, if it were fact-checked. I have a skewed perspective on AI, because ingesting vast amounts of texts is what I do. If it could take into account possibilities like Neil Postman brings up in The Disappearance of Childhood, that pre-literate man understood the world in fundamentally different terms than we do, then it could save us some time. Ultimately, if you never learn which questions to ask, the answers you find through whatever means are of a more limited value. Hope your corporate masters are treating you well!

Did the Ancient, Big European Banks push “Our Democracy” so that they could slowly pick off “Our Democraticaly Elected Representatives”, one by one; over centuries, over decades, over years.

Have we noticed the deafing silence about The non-release of the Epstein Files from most Senators and Representatives. Also most of Our Billionaire Oly-orks and Influencers?

I am noticing………

History is written, and paid for, by the victors, the bankers

Did the Imperialists, beginning with Constantine, push Christianity so they could over the centuries sustainably, er, ‘harvest’ those leaders who followed Christ’s teachings most closely?

Recently I have read much more about the 1400-1800 era and the more I read, the more I wonder about the implications of this: “While the peasantry supplied the food crops and surplus to export, as well as fresh bodies for king’s wars of choice, the merchants provided the imports and inputs for more and more advanced war-making, and the money-lenders supplied the financing. ”

A few weeks ago I started reading “Monarchy or Money Power” by R. McNair Wilson. Written in 1934, it is rather obscure and discusses the economic issues and manipulations even Kings were at the mercy of. Fairly interesting so far.

Did you actually read the post? It appears not. There was a shift in the medieval period in some parts of Europe towards governance arrangements that curbed the power of aristocrats in favor of their subjects. This is widely seen as a precursor to constitutional limits on royal/elite power.

It appears you’ve stuck your fingers in your ears and are yelling “nyah nyah nyah” because this post does not hew with your stereotyped “one size fits all” beliefs about that era.

I read Vicky Cookies’ comment as a gloss on Adam Smith’s chacterization of monarchs creating corporations to curb princely power. Is this unrelated to the arguments of the article?

1. A quick search does not support your reading of Smith to be widely accepted.

2. Yes, because this post is not about kings but a much larger class of nobility having to cede power to non-nobles.

3. It is hardly controversial that it was the merchants and emerging bourgeois who competed for power with landed aristocracy in the 1600s to 1900s, arguably up through the start of World War I. I never used the word “peasant” and suggesting the article or I did is Vichy Cookies’ and your straw man.

The great sociologist Barrington Moore, in his classic The Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, found that countries that had a bourgeois revolution became democracies, while those that had peasant revolutions evolved in an authoritarian direction.

Continuous warfare between competing “powers”, “kingdoms”, or “states” or “polities” existed in Asia or Africa as much as Europe, in the Middle East, or Eastern Europe as much as Northern or Western Europe. Why the latter two regions pulled ahead or developed more advanced fiscal systems or so is never going to be explained by simple sequences such as: kings fighting, needing money, borrowing money, conceding rights, magically constitutionalism appears, hey presto we have rights and are so much more advanced than the jungle out there (China? Japan ? –not in our database, we call them extra-systemic and they go away). Old fashioned ideas served with dollops of methodology. There”s no real historical control here. Pure description claiming to explanation

Erm, it is generally widely known that Europe had an advantage in producing economic surplus in the medieval through modern era due to its river system and favorable conditions for producing caloric surpluses, particularly through the cultivation of livestock. That alone explains many differences between Europe and the rest of the world then.

It is not clear to me that India and China had inferior agriculture compared to Europe before the Industrial Revolution. Incidentally, “favorable conditions for producing caloric surpluses, particularly through the cultivation of livestock” were credited as important for the rise of steppe empires of ancient Turks and Mongols, while The Netherlands and England relied on Baltic trade to secure enough food.