Yves here. This post focuses on the inherent contradiction in with stablecoin and digital currencies pegged to real world currencies: they either need to be fully backed by traditional currencies in order to be secure, which wrecks most of the profit potential for providers, be implicitly or explicitly backstopped by government, or face limits on use and periodic crises and “runs”. The US approach relies on regulation (good luck with that). China’s on the surface looks more robust but still fails to resolve the underlying conflicts.

By Eduardo Levy Yeyati, Plenary Professor of Economics and Public Policy Torcuato di Tella University and Sebastian Katz, Director, School of Economics, and Professor of Money, Credit and Banking and Economics University Of Buenos Aires. Originally published at VoxEU

Digital currencies pegged to fiat money face a built-in tension between credibility and competition, creating a ‘stablecoin paradox’. This column analyses the competing frameworks of the US and China to address the paradox. The US (under the GENIUS Act) combines strict reserve rules for privately issued, fully backed dollar stablecoins with market incentives that encourage expansion. Meanwhile, China’s approach centres on a central bank digital currency deployed domestically and extended across borders. Further expansion of the digital currency system will require backstop access, global coordination on regulation, limits on intermediation, and integration with payment systems.

Two years ago, we argued that digital currencies pegged to fiat money face a built-in tension: to keep credibility, they must operate like a currency board — holding fully liquid reserves to guarantee redemption at par — yet commercial incentives push them towards leverage and intermediation, undermining that very discipline. Because the latter seemed to be the ultimate goal of the former, we labelled this dilemma the ‘stablecoin paradox’ (Levy Yeyati and Katz 2022).

What was once theoretical is now a reality as the US and China escalate competition over global payments, monetary sovereignty, and the architecture of money itself.

The passage of the US GENIUS Act in July 2025, creating the first federal framework for stablecoins, and China’s rapid deployment of the e-CNY alongside its wholesale cross-border central bank digital currency (CBDC), mBridge, have brought the paradox to the heart of the international monetary system. The stakes are high: control over trillions in cross-border payments, the effectiveness of sanctions, and the balance of economic power in a digital world.

In this column, we argue that:

- The US approach tests the paradox at scale by combining strict reserve rules with market incentives that encourage expansion — and potential erosion — of discipline.

- China’s approach appears to sidestep the paradox through direct central bank issuance, but competitive pressures push it toward private yuan-pegged stablecoins that reintroduce the same tension.

- The global context — fragmented regulation, geopolitical rivalry, and the borderless nature of digital money — makes sustaining monetary discipline more difficult than in any previous era.

America’s Regulatory Gambit

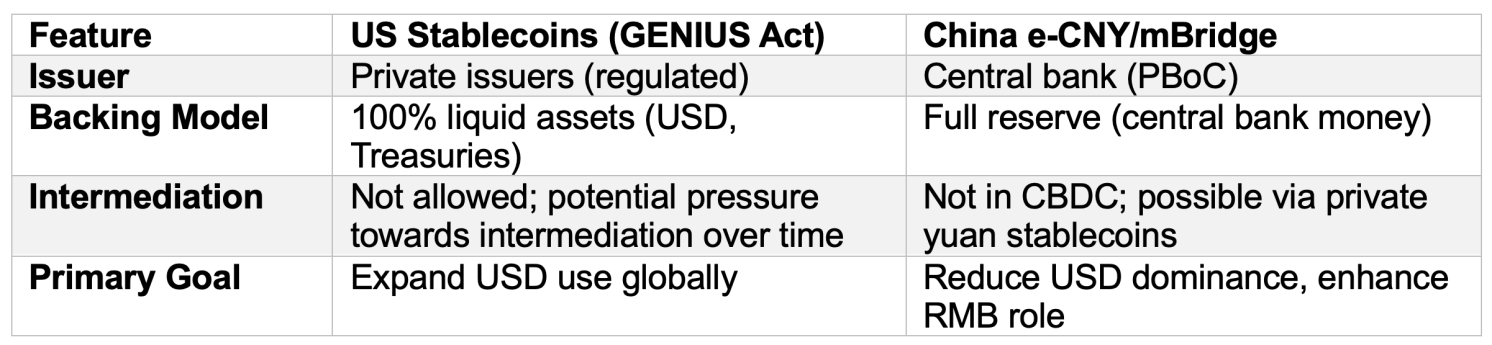

The GENIUS Act requires stablecoins to maintain 100% backing in liquid, safe assets — US dollars, short-term Treasuries, repos, or insured demand deposits. In principle, this mirrors a currency board: full reserve coverage and strict convertibility at par (BIS 2025). The Act also creates a dual regulatory structure between federal agencies and states, and mandates technical capacity to freeze or burn tokens under lawful order.

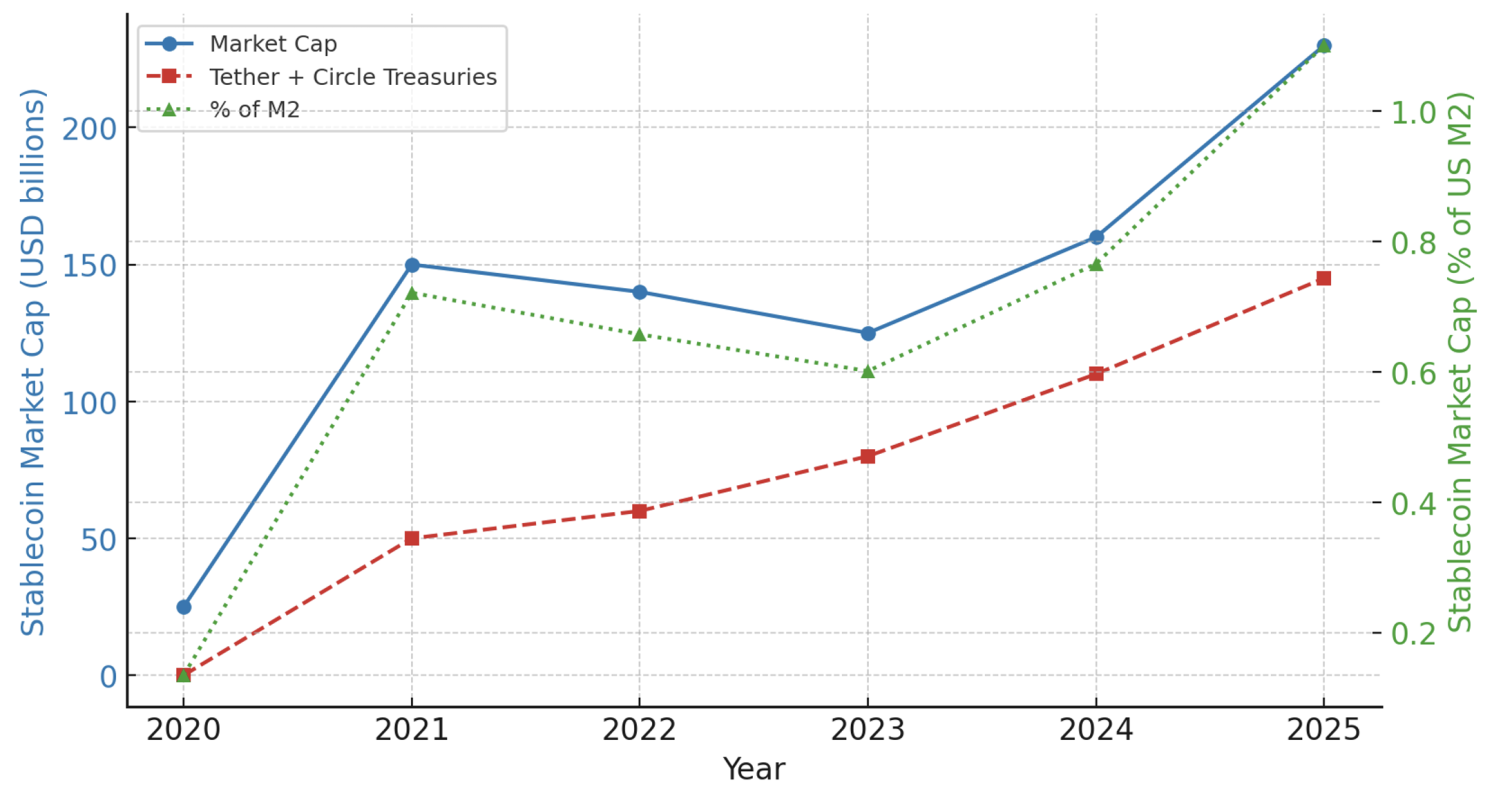

The strategic intent is clear. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent projects that the stablecoin market — now around $250 billion — could reach $2 trillion by 2028, vastly expanding global dollar use. Stablecoin issuers already hold over $140 billion in Treasury bills, making them, collectively, a larger holder of US debt than Germany (Ahmed and Aldasoro 2025).

Yet scale is the problem. As the market grows, issuers face pressure to generate higher returns, tempting them towards secondary money creation — using reserves to fund loans or longer-term investments — eroding the currency board discipline (Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli 2019).

History shows how fragile such discipline can be under stress. Argentina’s currency board collapsed in 2001 when capital flight forced reserve depletion; Hong Kong famously held its peg in 1998 only through costly interest rate spikes and coordinated asset purchases. In both cases, the credibility of ‘full backing’ depended on the ability to endure speculative pressure — something private stablecoin issuers, lacking central bank powers, cannot replicate.

The macro-financial consequences depend on where the inflows come from:

- If funds shift from government money market funds, the impact on Treasury yields may be minimal — merely reshuffling holders.

- If funds come from bank deposits, banks may face higher funding costs and reduced lending capacity, reshaping the credit channel of monetary policy.

This banking disintermediation — where money creation shifts from banks to stablecoin issuers holding only liquid assets — would move the system towards narrow banking. Such systems avoid credit risk but lack elasticity to respond to shocks – the core of the stablecoin paradox (Bank of England 2021).

Figure 1 Stablecoin market growth vs. US M2 and Treasury holdings, 2020-2025

Sources: CoinGecko global stablecoin data; industry press (AINvest, Yellow) for Treasury holdings; FRED (M2SL) for US M2. Market cap refers to all global stablecoins; ~97% are US dollar-pegged. Treasury holdings are combined USDT + USDC estimates from issuer attestations. M2 values are approximate annual averages in billions of US dollars. Shares of M2 are rounded and illustrative.

As the Financial Stability Board (FSB) has noted, “[s]ystemically important banks and other financial institutions are increasingly willing to undertake activities in, and gain exposures to, crypto-assets” (FSB 2022). Were these activities to depart from full-reserve models, they could reintroduce leverage or maturity transformation risks.

China’s Digital Yuan

Whereas the US strategy under the GENIUS Act relies on privately issued, fully backed dollar stablecoins, China’s approach centres on the e-CNY — a central bank digital currency (CBDC) — deployed domestically and extended across borders through mBridge.

China’s e-CNY is the most advanced central bank digital currency in the world, with over 260 million users and $7.3 trillion in cumulative transactions. Issued and backed directly by the People’s Bank of China, it avoids private-sector intermediation pressures — on paper.

Table 1 US versus China digital currency models

Its wholesale counterpart, mBridge, connects central banks from Hong Kong, Thailand, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia on a shared distributed ledger. By enabling near-instant atomic settlement of cross-border transactions in multiple currencies, mBridge removes the need for sequential account updates in correspondent banks — a key vulnerability of SWIFT. In practice, this means bypassing intermediaries that are often in jurisdictions able to block, delay, or monitor payments, a feature with clear geopolitical appeal.

The geopolitical goals are explicit. People’s Bank of China (PBoC) Governor Pan Gongsheng has framed central bank digital currencies as a way to safeguard against the ‘weaponisation’ of payment systems through sanctions. In parallel, China is promoting the yuan for trade settlement: Russia–China trade is now 92% settled in rubles or yuan, and CIPSprocesses $45.6 billion daily.

Yet, the paradox persists. While pushing the e-CNY central bank digital currency, China has opened the door to yuan-pegged private stablecoins from firms like JD.com and Ant Group. Officials worry that without competitive yuan stablecoins, cross-border payments will remain dominated by dollar stablecoins — a ‘strategic risk’ in the words of former Bank of China Vice President Wang Yongli.

This dual strategy — centralised central bank digital currency plus private stablecoins — recreates the currency board dilemma. To grow, private yuan stablecoins will face the same temptation toward intermediation and leverage as their dollar counterparts, potentially undermining their own stability and, by extension, monetary control.

The Geopolitical Stakes: Payments, Sovereignty, and Stability

The appeal of stablecoins is clear: instant cross-border settlement, 24/7 availability, and lower intermediary costs compared to the two- to five-day lags of correspondent banking (ECB, 2025). Cross-border stablecoin transactions now exceed $2.5 trillion annually, up tenfold since 2020.

This speed creates trade-offs:

- For advanced economies, widespread use of foreign stablecoins could weaken sanctions power (Brookings, 2025).

- For emerging markets, dollar stablecoins risk accelerating cryptoisation — digital dollarisation that erodes domestic monetary policy effectiveness (IMF 2025).

Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli (2019) warn that stablecoins crowd out local currencies where inflation is high and payment systems are inefficient, with the inclusion benefits of cheap remittances coming at the cost of policy autonomy. Nigeria’s eNaira experiment shows the challenges: uptake has been slow domestically, but cross-border stablecoin use by Nigerians abroad has grown, bypassing both the eNaira and the local banking system.

China’s Belt and Road projects are embedding e-CNY central bank digital currency rails into infrastructure from Southeast Asia to Africa, aiming to bypass Western banking. The US, via the GENIUS Act, is trying to extend the reach of dollar stablecoins. Both strategies increase cross-border connectivity — but also cross-border vulnerabilities.

Fragmented Regulation and the Risk of a ‘Race to the Bottom’

The GENIUS Act’s dual federal-state oversight enables regulatory arbitrage towards lenient jurisdictions like Wyoming.

Internationally, frameworks vary widely: Hong Kong’s rules differ from Singapore’s, the EU’s MiCA regime, and the UK’s upcoming standards. Such fragmentation invites a ‘race to the bottom’ on backing and disclosure requirements.

Market concentration amplifies these risks. Tether, with a 62% market share, operates under looser disclosure than federally regulated rivals. If a major issuer failed — whether through the loss of the peg, a run, or reserve impairment — spillovers could hit short-term funding markets through disorderly liquidation of Treasuries (Financial Stability Board 2022). The TerraUSD collapse in 2022, which wiped $400 billion from crypto markets, shows how quickly confidence can unravel when currency board discipline is breached (BIS 2022).

Even fiat-backed stablecoins fall short of central bank money’s singleness — the principle that all money in a system is interchangeable at par — because they lack direct access to central bank settlement (Garratt and Shin 2023). This was the flaw of 19th-century private banknotes, and it remains today.

Policy Implications: Sustaining Discipline in a Bborderless System

Despite their different architectures, both approaches face an identical challenge: how to scale a digital currency system while preserving the credibility of its backing. Competitive pressure pushes issuers — whether private or public-private hybrids — toward compromises that weaken discipline.

A few guiding principles emerge:

- Backstop access. Without access to central bank liquidity or deposit insurance, even fully backed stablecoins can face self-fulfilling runs (BIS 2025).

- Global coordination. Stablecoins are borderless; regulation is not. This reflects the financial trilemma between domestic financial stability, financial integration, and regulatory autonomy (Schoenmaker 2009): one cannot fully achieve all three. Avoiding regulatory arbitrage — and the potential for financial disruption — will require cross-jurisdictional standards on reserve quality, disclosure, and redemption rights.

- Limits on intermediation. To preserve currency board credibility, regulators must strictly limit leverage and related-party lending by stablecoin issuers, especially if bank-affiliated.

- Integration with payment systems. To achieve the benefits of digital innovation while preserving the solid foundation of existing systems and singleness, central banks could explore tokenised deposits backed by digital public money to preserve par convertibility without fragmenting the monetary base.

The Paradox Goes Global

The stablecoin paradox is no longer an abstract concept — it is the operating reality of a digital currency arms race between the world’s two largest economies. The US is testing whether strict reserves can survive market incentives for growth; China is testing whether centralisation can survive competitive pressures for private innovation. Both face the same structural trade-off: stability requires discipline, but growth demands elasticity.

In the analogue era, currency boards and hard pegs repeatedly failed under such pressure. The digital age offers new tools, but not an escape from monetary fundamentals. The winner may be whichever system can best resist the erosion of its own monetary discipline.

See original post for references

My understanding is that the Genius Act was designed to use stablecoins, backed 1:1 with the US$, to increase the demand for US Treasuries and keep the US dollar strong. It seems like it was also goose the value of crypto as well, or at least create an incentive to do so – the higher the value of crypto, the more stablecoins needed, and by extension more Treasuries to back it. Seems like a YUGE grift, but there we have it. As I’ve mentioned before, the more you learn about finance, the more it resembles check kiting, except finance is done by serious people in suits.

A few things I’m not understanding though. The article mentions pressures to create a yuan stablecoin, but doesn’t explain well why this would be necessary. One purpose of stablecoins is to ease conversion of privately issued cryptocurrency to US$, since you can’t go into the packie and buy a six pack with crypto. But with a government backed digital currency, you’re already dealing with government backed money, so why the need for a matching stablecoin? Why would the Chinese government allow private companies to intrude?

The article also notes that while stablecoins are backed 1:1 by US$ in theory, there is some question as to whether they actually are. And if there is some question, why in the holy hell would anyone want them mixed in with actual government issued fiat? I know why the grifters in the US would, but surely China isn’t that dumb.

It also mentions the need to scale while preserving the credibility of its backing. Presumably a CBDC would be backed by faith in the government that’s issuing it, as is currently the case with regular fiat.

Of course, a main reason for any CBDC is the potential for government surveillance. Presumably even privately issued stablecoins would be subject to some surveillance as well – we can’t have drug cartels anonymously driving the demand for US Treasuries, can we? (We probably can in this current environment, but let’s pretend for the sake of argument that we have a less venal government) So there goes the whole fantasy that crypto is anonymous and decentralized.

All I know is that when finance gets so complicated and convoluted (anyone like to sample a synthetic CDO?), it’s time to hide the good silver and hold tight to your wallet. This really is the stupidest timeline.

My understanding is a big reason for the stablecoin rules is to bring Tether, which is widely believed to have markedly less than full reserving of its coin, into full or at least fuller reserving so as to prevent a run and potentially even a crisis.

Right, and that is a way to goose the value of privately issued crypto. But I still don’t see why there would be a yuan stablecoin to go along with a Chinese government CBDC. One digital yuan would be equivalent to one non-digital yuan, whereas one digital bitcoin is clearly not equal to one non-digital US$, so we have stablecoins like Tether to ease conversion. Any thoughts on that?

Huh? If stablecoin players can’t make enough money in stablecoin due to inability to leverage, the market should shrink, not grow. Investors are clearly indifferent to coin security and terms.

I realize I’m not explaining myself all that well. I’d understand all this better if I’d ever seen how one of these crypto exchanges works first hand, but I’m a little averse to setting my money on fire.

But my understanding is that stablecoins are supposed to bring some stability to the crypto market, and are not supposed to be an investment by themselves. Partnering with the US government would bring even more stability, keeping the crypto market large, and by extension keep up the demand for treasuries. I guess I don’t understand why there would be stablecoin “players” at all – the whole point is the value stays steady. I picture them as a means to exchange crypto for fiat or vice versa. So is the idea that stablecoins backed by US$ could be used directly in ForEx trading? But if so, why not just use dollars or Treasuries directly? Sorry if I’m being dense here – I just want to understand how this grift all works.

…and by extension keep up the demand for treasuries.

I wonder if this is the US main goal. I also wonder how much counterbalance this will provide against reduced demand by China’s potential non dollar international settlements.

Interesting.

They won’t work if providers can’t make what they deem to be an adequate return. You’ll seem them demand some leverage to do so, which will undercut the safety pretenses.

There has long been an analogous idea in banking, of “narrow banks’ allowed to do only very safe things with depositor money. Regulatory experts love it. Does not work commercially. No narrow bank has ever been started or even set up as a separate unit in a broader bank.

“..why there would be a yuan stablecoin to go along with a Chinese government CBDC…”

Plausible deniability. Abstraction has its uses. The mice need somewhere to play. I gathered the US sought to distinguish itself as the “freedom” exchange, no CBDC and all; perhaps China finds merit in competing with that syndicate?

Thank you.

If I’m reading this right China’s main objective is developing a tool to remove both the US and the dollar from international settlements (two sound ideas!). Meanwhile, it’s unclear what the main objective is in the US, who is busy trying to shore up the substructure before there’s another crisis.

To me, China’s goal looks very doable. And China is country that gets things done.

That’s not what the post says. Please re-read the part about the digital yuan.

China can and is engaging in bi-lateral trade. It does not need a digital currency to do so.

Irrespective of the tech bells and whistles, bi-lateral trade results in the trade surplus country accumulating financial assets of the trade deficit country (see Greece in the Eurozone as another example). This over time becomes destabilizing unless trade is pretty balanced. But mercantilists like China don’t want that. They won’t submit to bancor-type arrangements to curb trade imbalances because they are actively seeking them and separately, those financial arrangements also entail a loss of national sovereignity.