The Marine Corps’ new Pacific island strategy, articulated in its Force Design 2030 planning documents, envisions small units deployed across the Pacific island chain, armed with missiles and sensors to strike Chinese shipping and contest maritime access. Branded as Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), the concept seeks to adapt the Corps to great-power competition by positioning Marines inside China’s defensive perimeter, where they could harass adversary forces, support naval maneuvers, and complicate Beijing’s plans for regional dominance. Advocates praise the plan’s boldness and innovation, presenting it as a decisive contribution to deterrence and warfighting in the Western Pacific.

Yet history and geography suggest the strategy is more fragile than its champions admit. By positioning Marines in austere island outposts deep inside China’s missile envelope, EABO risks repeating the fate of Japan’s Pacific garrisons in the Second World War: isolated, unsupplied, and defeated not by battlefield collapse but by starvation and exhaustion. In practice, the plan asks small detachments to endure on distant islands under the constant threat of missile attack and interdicted supply lines, a test of logistics and survivability that may prove fatal to the forces committed to this mission.

The Logistical Problem

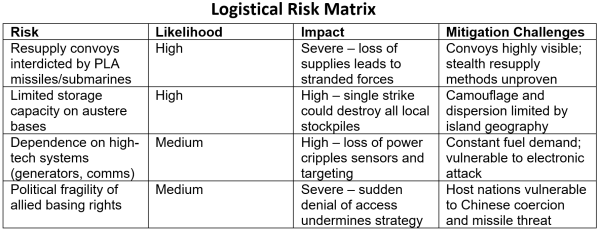

Geography favors China: its supply lines are short and secure, while America’s are long and exposed. Expeditionary Advanced Bases would need steady deliveries of fuel, food, spare parts, and precision munitions. These items are bulky, heavy, and require specialized handling. Modern warfare’s high tempo would quickly outpace resupply capacity. Supplying widely distributed outposts by sea or air would present targets for interdiction by China’s formidable ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) and missile strike capabilities.

EABO relies on fragile Supply Nodes. Small airstrips, ports, or pre‑positioned caches could be easily targeted by long‑range Chinese missiles. Unlike WWII, where concealment and dispersion were possible, modern satellite and drone surveillance makes hiding supply points nearly impossible. Moreover, the Marines’ strategy relies on a kind of shell game mobility, with detachments moving frequently among islands to thwart counter attacks. This would require a a mix of pre-positioned stocks and constant transport alongside troops.

The strategy is high-tech dependent. The Marines will rely on generators, radars, digital networks, and secure communications. These systems demand constant upkeep and fuel, creating vulnerabilities and burdens absent in WWII island garrisons. Proposed innovations to resolve logistics problems, such as drone resupply, autonomous surface craft, or undersea caches, remain largely experimental. In a high‑intensity conflict, the volumes required are likely to overwhelm such methods.

Evacuation and rotation of troops in contested islands is as difficult as resupplying them. If units become depleted or compromised, extraction could be costlier than reinforcement, forcing commanders into difficult choices. Treatment of wounded would be a difficult problem, since U.S. forces have become accustomed to prompt field evacuation of seriously injured soldiers, something that may not be feasible for detachments on distant islands.

Chinese Reconnaissance and Missile Strike Capability

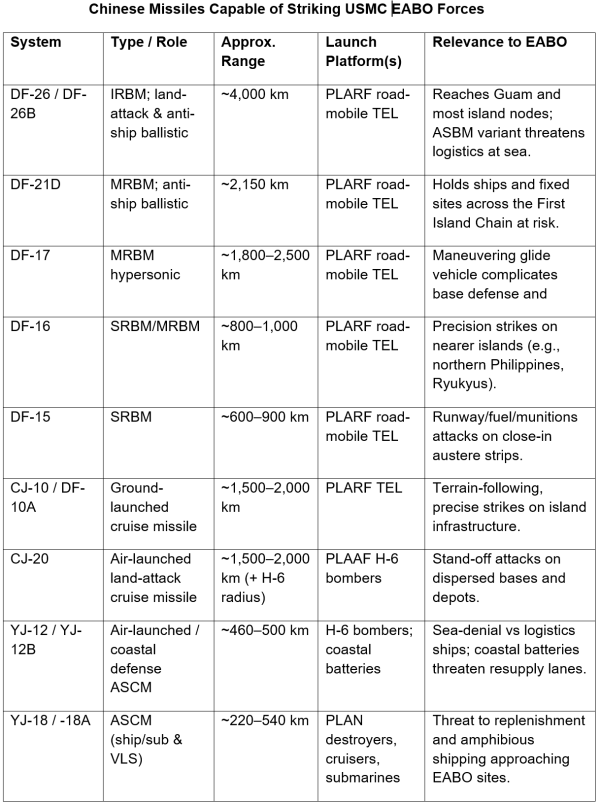

A key danger to the U.S. Marine Corps’ island strategy is the vulnerability of logistics shipping to modern Chinese surveillance and strike systems. China has developed a sophisticated orbital reconnaissance network composed of Yaogan synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites, electro‑optical satellites, and electronic intelligence (ELINT) platforms. These, combined with the Beidou navigation constellation, provide the People’s Liberation Army with the ability to detect, track, and cue missile attacks against large surface targets at sea.

China’s missile arsenals vastly exceed those of the U.S. in theater-range quantities. Combined with a dense surveillance network—satellites, UAVs, maritime drones, and over-the-horizon radar—any island outpost would be rapidly detected once operational. At that point, mobile units face a difficult choice: clump together (easier to target) or disperse (harder to supply). Either pathway invites defeat.

The Chinese ‘kill chain’ would likely operate by detecting supply ships through satellite radar or emissions, relaying coordinates to the PLA Rocket Force, and then launching long‑range anti‑ship ballistic missiles (such as the DF‑21D or DF‑26). While orbital satellites do not provide continuous coverage, China integrates them with over‑the‑horizon radar, UAVs, and maritime patrol aircraft to maintain sufficient maritime domain awareness. The net result is a credible ability to threaten slow and vulnerable logistics ships, especially fuelers and transports, with long‑range missile strikes.

Historical Parallel: Japanese Logistical Defeat in WWII

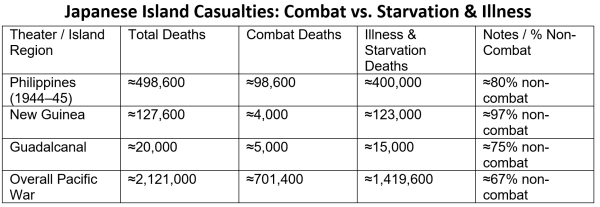

The vulnerabilities facing U.S. Marine island detachments echo the tragic fate of Imperial Japan’s garrisons during the Second World War. Japan constructed a vast perimeter of fortified islands—Rabaul, Truk, Saipan, Peleliu, and many others—to shield its maritime lifelines. Initially formidable, these outposts became death traps once the U.S. Navy and submarine force severed supply lines. American strategy of ‘island hopping’ deliberately bypassed many strongholds, isolating them and leaving tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers to perish.

Cut off from food, medicine, and ammunition, Japanese garrisons endured catastrophic attrition. At Rabaul, more than 100,000 troops were effectively imprisoned, surviving on minimal rations until Japan’s surrender. On smaller islands, such as Wake and Tarawa, defenders faced both bombardment and starvation. By 1945, an estimated one-third of Japan’s Pacific island fatalities were the result not of direct combat but of starvation and disease. Contemporary accounts describe skeletal soldiers, forced to forage for roots, insects, and bark in order to survive. Once resupply was severed, Japanese island forces collapsed, not from combat, but from hunger, disease, and exhaustion.

The U.S. Marine Corps’ modern island strategy risks encountering a similar dilemma. While today’s forces possess advanced weapons and communications, their dependence on high-volume resupply of fuel, munitions, and spare parts may make them just as vulnerable to strangulation. The lesson of Japan’s defeat is clear: in island campaigns, military outcomes are determined by logistics, not valor.

Air Mobility Vulnerabilities: The Osprey Problem

The MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor transport aircraft is central to the Marine Corps’ vision of Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations. With its extended range, vertical lift capability, and ability to move troops and supplies rapidly between islands, the Osprey is designed to provide the mobility backbone for dispersed Marine units across the Pacific. Without it, the concept of rapidly shifting small detachments from one austere base to another loses much of its practicality.

Yet the Osprey is also one of the most vulnerable assets in a high-end conflict. It is large, radar-visible, relatively slow compared to modern fighters, and lacks robust defensive systems. Chinese integrated air defenses—including long-range surface-to-air missiles and fighter patrols—would make forward operations perilous. The aircraft is also notoriously maintenance-intensive, requiring high levels of technical support that are difficult to sustain on isolated islands, while its heavy fuel consumption magnifies the burden on already fragile supply lines.

If Ospreys cannot operate safely forward of the Second Island Chain, the Marines’ ability to shuttle troops, equipment, and munitions between islands collapses. This would leave the EABO concept reliant on sealift connectors, drones, or pre-positioned stockpiles—methods that are slower, less flexible, and in some cases not yet viable. The Osprey’s fragility therefore undermines the central promise of Marine mobility. It reflects the broader pattern of over-reliance on technology in the face of hostile geography and superior missile capability.

MV-22B Osprey – Easy prey?

Time as an Adversary

The Marine Corps’ island strategy is vulnerable to the passage of time. China’s military capabilities in the Pacific are not static; they are expanding at a pace that outstrips U.S. force growth. Each year brings more satellites for maritime surveillance, more accurate and longer‑ranged missile systems, and larger numbers of advanced combat aircraft. These expanding surveillance, strike, and aviation components steadily tighten the noose around any potential forward U.S. outposts.

By contrast, the Marine Corps’ own assets are not growing in either quantity or quality at a comparable rate. The number of Ospreys, missile launchers, and specialized logistics systems is limited, and procurement cycles ensure only marginal improvements over the coming decade. The imbalance is structural: China is building mass and redundancy into its regional strike complex, while the U.S. relies on relatively few, expensive platforms that are hard to replace.

Time will magnify this asymmetry. The feasibility of the EABO strategy will diminish further as China’s growing reconnaissance and strike power overwhelms the planned USMC capability. In this respect, the strategy is not merely fragile; it is based on a shrinking margin of safety that erodes with the passage of time.

Too Many Flaws

EABO’s success depends on partner nations—Japan, the Philippines, Palau, among others—granting basing access. But China’s political coercion and diplomatic pressure can undermine these agreements at critical moments. Moreover, these host countries would become targets themselves, raising the risk of escalation that might deter the U.S. from responding or resupplying in kind. Allies may then withdraw access to avoid devastation—a fatal blow to the concept.

Even in a best-case deployment scenario, the islands serve denial rather than closure. China can reroute shipping via southern routes through Indonesia or leverage overland corridors from Central Asia and Russia, preserving critical supply lines. This adaptive resilience diminishes the strategic value of island-based interdiction.

Worse still, these island sites may serve less as barriers and more like sacrificial tripwires. Their loss could be heralded as an overture to broader war, galvanizing public and political momentum—but at disproportionate cost. Instead of denying Chinese access, the Marines risk becoming symbolic pawns whose destruction triggers escalation on terms of Beijing’s choosing.

The Marine Corps’ shift toward distributed island operations is imaginative, aligning with modern warfare’s emphasis on dispersion, precision fires, and joint sea‑land integration. Nonetheless, the strategy underestimates core vulnerabilities: logistics, surveillance, massed missile fire, political fragility, and China’s strategic redundancy. A pessimistic analysis indicates that, rather than securing Pacific access, future Marines may end up isolated and ineffective.

How Did We Get Here? Institutional Origins of the Strategy

The emergence of the Marine Corps’ Pacific island strategy cannot be understood solely in operational terms. It is equally a product of institutional dynamics within the U.S. defense establishment. After two decades of counterinsurgency, the Corps sought a new mission to secure its relevance and budgetary share. The pivot to the Pacific offered that opportunity, and the concept of small, forward-based, missile-armed detachments promised a unique contribution that distinguished Marines from the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

This search for relevance encouraged optimism about what elite, high-tech forces could achieve. In embracing Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, Marine planners drew upon a longstanding cultural faith in the superiority of small, highly trained units equipped with advanced technology. Yet this faith risks becoming a modern parallel to Imperial Japan’s exalted ethos of sacrifice, one that could not overcome the brutal realities of starvation and disease.

The strategy was also shaped by inter-service competition and bureaucratic fashion. The Marines needed a distinctive mission that avoided redundancy, and island-based sea denial fit that role. The Pentagon, moreover, has long rewarded concepts that sound innovative—distributed operations, multi-domain warfare, mosaic deterrence—regardless of whether they are logistically sustainable. Once enshrined in Force Design 2030, the strategy gained bureaucratic momentum, making dissent inside the service difficult.

Political considerations reinforced the concept. Forward-deployed Marine detachments offered policymakers a visible, seemingly economical deterrent against China, one that did not require vast new bases or escalatory deployments of heavy forces. In this sense, the strategy reflects not only military doctrine but also Washington’s preference for solutions that appear bold and affordable on paper, even when their battlefield feasibility is doubtful.

Thus, the EABO strategy is less the product of cold operational logic than of institutional incentives and cultural predispositions. It reveals a system willing to overestimate the power of elite troops and technology while underestimating the hard arithmetic of supply. In that gap between aspiration and reality lies the danger of repeating Japan’s Pacific defeat in a new guise.

This pattern of self-delusion is not unique. Military victors often suffer from strategic illusions, mistaking the glamour of elite forces or dazzling technology for the true foundations of success. The United States triumphed in WWII because it mastered industrial production and secured its supply lines. Yet in the postwar decades, Washington increasingly recast victory as the product of elite troops and technological superiority. This is the basis of today’s belief that Marine troop quality, enhanced by advanced sensors and weapons, can overcome hostile geography and an uncertain logistical margin. It is the Axis error repeated—privileging the glory of martial excellence over the plain truths of logistics.

Conclusion

If the Marines are to play a decisive role in a Pacific conflict, it may be wiser to return to a function closer to their historic strengths. Rather than fighting in scattered island outposts, they could serve as a mobile reserve: dispersed for protection, then concentrated to exploit gaps as they emerge in the fluid battle space. This would align with the Corps’ legacy as an adaptable expeditionary force, providing flexibility and striking power where it matters most, while avoiding the trap of garrisons vulnerable to logistical defeat.

The problem at the heart of the Marine Corps’ Pacific island strategy is not a lack of courage or ingenuity, but a misplaced faith that technology and elite training can overcome immutable geography and logistics. By assuming that small, highly skilled units can succeed while isolated on distant islands, the strategy echoes the illusions of Imperial Japan, where leaders believed that martial spirit could sustain their troops even as supply lines collapsed. Today, the Marine Corps risks repeating that error. Wars are won not by isolated detachments, however skilled, but by forces sustained in depth. The hard truth is simple: logistics sustains combat power; valor alone cannot. EABO rests on the illusion that the best troops can prevail when left to wither in the far reaches of a hostile ocean.

“Moreover, the Marines’ strategy relies on a kind of shell game mobility, with detachments moving frequently among islands to thwart counter attacks.”

This sounds very energy-intensive, and perhaps that is the greatest vulnerability. (I do note Haig’s mention of “dependence on high-volume resupply of fuel”.)

“Contemporary accounts describe skeletal soldiers, forced to forage for roots, insects, and bark in order to survive.”

For a cinematic treatment of this, one can watch Kon Ichikawa’s “Fires on the Plain” (1959) — bleak, but extraordinary.

Study Nimitz!

Defense of Wake Island comes to mind.

The two runways on Tinian and base are being beefed up, modernized.

That said the other side should also consider studying Nimitz which is modernized plan Orange from the U.S. ‘ pacific empire plan of 1900.

USMC does neea reason to keep Smedley Butlers in MEU s.

“The two runways on Tinian and base are being beefed up, modernized.”

Tinian of all places…

FFS.

The mission on Hiroshima….

It has long runways.

Another flaw with the plan, if an opponent takes out U.S forces (in a remote place)it would very likely never be reported on. Meaning military opponents of the U.S. could do clandestine operations blowing up bases located so remotely that no independent journalist would ever know it happened. The attackers would have no need to publicize their victory, and the Pentagon would not want it known that they had lost (yet again) to a more Wiley opponent.

I can imagine the South Pacific crawling with Al Qaeda, Banderites, Russians, Chinese, Somali, Venezuelans, (basically anybody that has a new or old grudge) looking to practice, train, and learn how to defeat U.S. military elements. SP will become the playground for more motivated factions to defeat less motivated factions.

The funny thing (in a grim way) was that Rabaul was fairly well off as far as Pacific Island garrisons went: the soil was fertile, fish was plentiful, and most Japanese soldiers were experienced farmers and fishermen: thus there were more than 100k stuck where Allies expected no more than 30 to 40k because Japanese farmed and fished enough to sustain them. The horror stories were on places like Jaluit (I think) and others in the middle of high seas, with poor soil and limited fishing opportunities…

I don’t know how many US Marines know gow to farm and fish under primitive conditions.

Sounds utterly silly, therefore inevitable. Of course by 2030 Trump will be gone and the Department of War named back to the Defense Department and the Gulf of Mexico restored as well.

Also what about “R and R” off the middle of nowhere? Maybe the Pentagon can supply the boys with AI girlfriends via Starlink.

Army MDTF concept also seems to operate within this framework.

Excellent piece, especially the section explaining the “Institutional Origins of the Strategy”

Best part if the entire posting, IMO.

But I will quibble about no mention of how the US first suffered the flaws of island fortresses- the loss of the Philippines come to mind. Most of the US bases were quickly over-runned and surrendered within weeks of Pearl Harbour. (Yes, the Japanese failure does offer the most in-depth analysis, yet the American one offers the most emotive one).

So, they want to transition to airborne forces. If marines want to be trans-branch, they should get an appropriate striped flag. :)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crayones_cera.jpg

MV-22 was supposed to replace the MH-46 (somewhat smaller than Army CH 47). Early idea was to replace H-53, but that is overcome by events, H-53K is coming.

Combat range 630 miles, empty range 2000.

It is vertical/short take-off and landing.

Vertical take off weight 52,000 (56000 short take off) pounds: dry weight 33000, fuel load 6000 pound, maybe in vertical 13000 pounds cargo and passengers.

Cube/volume limit usually reached before weight limit. Dimensions 24′ by 6′ by 6′.

Probably need to have Amphibious ships in the mix!

Amphibious ships, boats, hovercrafts, and ekranoplans!

There does not seem to be any serious treatment of risk in the document. The WW2 parallel seems so obvious that I would expect some discussion of it, but it’s not in there.

We might charitably assume that it’s not part of the scope for this document and there are other documents or processes for addressing that. However, if I was writing a document on those terms then I would explicitly declare it out of scope (to avoid exactly this kind of ambiguity) and reference the other documents if they exist. They don’t even seem to have done that.

If this is an example of US strategic planning, it’s no wonder they get themselves into such trouble.

Not for nothing are the Marines being called “Missile Marines.” The previous Commandants of the USMC were being used as the enforcers of this “vision” and thumping down on all opposition but hard. Dissent was not allowed. And to do this mission, the USMC were being stripped of heavy equipment like tanks and capabilities as well. Jobs that the Marines used to do were abandoned and you had the Army go in to eat their lunch of course. How will the Chinese counter them? Perhaps by slipping in hunter-killer teams onto those islands by sub or taking them out with ballistic missiles after they are located by satellite feeds. All that high-tech gear gives off a huge signature. And if those Marines cannot be resupplied, I can see them doing a time-honoured practice by living off the land – meaning raiding villages and towns on those islands for food and equipment. The locals will love that. Marines used to specialize in forced entry but now? Take away the ‘Missiles Marines’ component and what do you have left that the Army cannot do?

Swim?

P.S. Does not apply to Ukrainian marines.

Another decent analysis, Haig.

On another level, I despair — and I’m not even American — at the sheer blockheaded inability of the US to recognize it’s not the 1990s any more.

But this denial of reality is a general Western thing, of course. This was just in the FT, with the even more moronic Europeans talking about creating a no-fly-zone against the Russians, as if this were 1991 against Iraq and Russia wasn’t technologically superior —

US offers air and intelligence support to postwar force in Ukraine: Washington prepared to contribute surveillance, command and control and air defence assets, say European officials

“….the postwar support would involve US aircraft, logistics and ground-based radar supporting and enabling a European-enforced no-fly zone and air shield for the country, the officials said.”

This also just in from Reuters —

Exclusive: US and Russian officials discussed energy deals alongside latest Ukraine peace talks

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-russian-officials-discussed-energy-deals-alongside-latest-ukraine-peace-talks-2025-08-26/

https://archive.ph/AMP3y

“On the same day as the Alaska summit, Putin signed a decree that could allow foreign investors, including Exxon Mobil, to regain shares in the Sakhalin-1 project. It is conditional on the foreign shareholders taking action to support the lifting of Western sanctions on Russia…

“The U.S. has placed several waves of sanctions on Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project, starting in 2022 and cutting off access to ice-class ships that are needed to operate in that region for most of the year.

The project is majority-owned by Novatek, which started working with lobbyists in Washington last year to try to rebuild relations and lift the sanctions.

“Washington is seeking to prompt Russia to buy U.S. technology rather than Chinese as part of a broader strategy to alienate China and weaken relations between Beijing and Moscow, one of the sources said.”

What don’t these knuckleheads understand about logistics?! Everyone can see in Ukraine that Russia’s proximity to the battlefield allows them to use their superior weapons, ISR, and logistics to throttle and surround ENTRENCHED fighters with relative ease (even with advanced NATO ISR hovering overhead. The expected ratio of of KIA has been turned upside down.

Don’t think China isn’t learning valuable lesson.

“in island campaigns, military outcomes are determined by logistics, not valor”

I would say in any extended conflict (especially between peers), and even most short-term conflicts, logistics is the key determinant. The Russian army’s ammo and fuel usage are mind-boggling, and the US no longer has the logistical capacity, as it was privatized – how long can the US fight with up to $400/gallon diesel as was charged in Afghanistan? But will Trump understand US logistical constraints? I can see him bored by the word.

The document reads like fabricated meaningless filler material generated by an app. The illustrations are comical, not serious.

Long story short. Just as the Russians have in Ukraine, China will always have ‘escalation dominance’ near their shores.

Even Yemen has ‘escalation dominance’ near its shores.