Yves here. This post unpacks another layer of why Trump’s tariffs are vastly more likely to accelerate America’s decline than spark a revival. While tariffs can be a useful element in industrial policy, via sheltering key industries that often get other forms of government support, across the board tariffs are far too blunt an instrument to prove to be salutary. Among other reasons, they increase costs of many inputs, which hurts competitiveness of many export categories.

One might ask, then, why has Russia fared well under broad baaed sanctions, which arguably have even more stringent effects than tariffs? First is that Russia is more of an autarky than any other country, is self-sufficient in virtually all critical resources, and has a large manufacturing base. Second, the “shock and awe” sanctions cut Russia off only from those nations that participated (and even then not fully so, witness the US still importing Russian uranium and the EU still importing Russian energy), Russia was still trading with many other key partners, particularly China, India, and Turkiye. Third, my impression is that aside from some critical areas like car and airplane parts, it was consumer goods that took the big hit. The Russian case suggests those are not as difficult to replace as industrial goods.

By Richard Baldwin, Professor of International Economics IMD Business School, Lausanne; VoxEU Founder & Editor-in-Chief VoxEU. Originally published at VoxEU

The new Trumpian tariffs are not the familiar protectionism G7 nations have applied for decades. Instead of shielding particular sectors, they wall off the entire American goods-producing economy from foreign competition. This is precisely the logic of 20th-century import substitution industrialization – a strategy widely tried, and widely abandoned, because it raised costs, bred inefficiency, and undercut export performance. The rise of global value chains turned such tariff walls from protection into destruction. No one has tried import substitution industrialization since – apart from America in 2025.

A 21st-century revival of a 20th-century mistake

America is running a bold economic experiment. Call it Economic Trumpism. Its core is disarmingly simple:

- Wall off America’s goods-producing economy from foreign competition and imported industrial inputs and hope industry flourishes inside.

No elaborate industrial policy. No bothersome planning. None of that old-fashioned stuff. Just a big, beautiful tariff wall to shield America from rapacious foreign competition. Best of all? According to the current US administration, it costs not a penny. Just the opposite: it shovels billions into the Treasury’s coffers.

Why is this an experiment? Don’t all nations apply tariffs?

The answer is simple. Trumpian tariffs are not the familiar tariffs aimed at protecting a favoured sector; the President has put up a tariff wall around the entire economy. And that’s not something that has been tried for decades in a G7 nation.

From Sectoral Shield to Protectionist Wall

To see the distinction, recall a classic US example. As part of a trade spat with Europe, the US put a 25% tariff on imported pickup trucks. Since it was in retaliation for Europe’s regulations that banned US chicken meat, the 25% tariff is still called the ‘chicken tax’. Ordinary autos weren’t included, so their tariff was negotiated down to about 2.5%.

The asymmetry reshaped what US producers built (large pickups) and what foreign firms avoided exporting to the US. For example, Toyota largely abandoned direct export of pickups to the US and instead built factories in America to avoid the tariff. That is how narrow tariffs ‘work’: they shift resources for a few sectors.

But broad tariffs, covering most manufactured goods, are a different animal. They raise input costs across the board, they invite retaliation and trade diversion, they fragment supply chains, and they induce tariff-engineering (re-routing, re-labelling, re-designing to slip under the wall). The mechanism isn’t a gentle nudge; it’s a shove applied to every factory in the country, including those that rely on imported intermediates to stay competitive.

Structuralist Development Economics and Import Substitution Industrialization

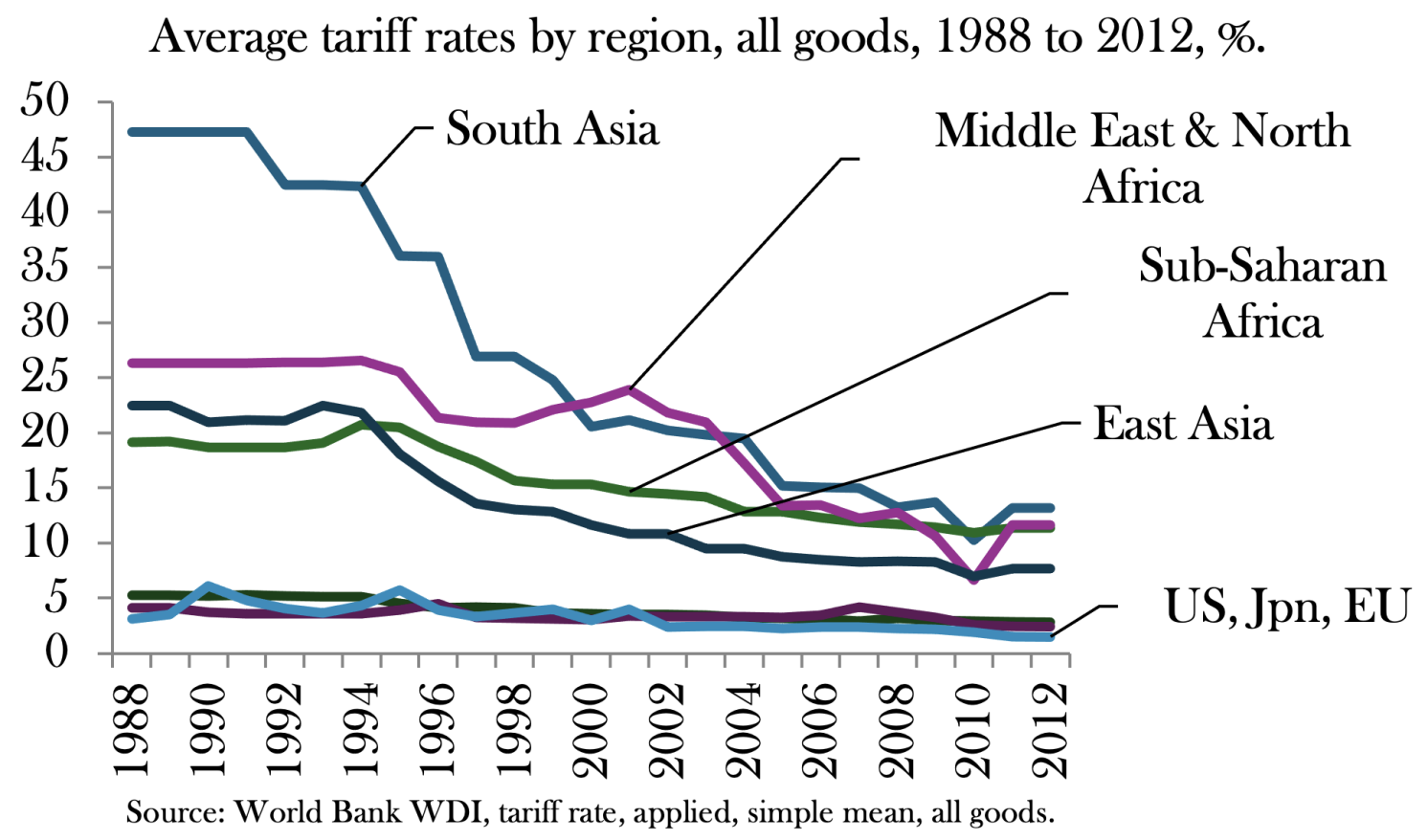

Trump-like, high and broad tariffs were very popular in developing nations (as we called them back when they were doing it) up to the 1990s. Indeed, almost all developing nations believed that putting tariffs on everything from everyone was a winning policy. And when I say high, I mean high! Levels that would make Donald Trump blush (metaphorically). The US average tariff is set to raise to about 20% from its current 9% (it was under 3% in 2024). That is nothing compared to the standard operating procedure in Latin America by in the 1970s and 1980s (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Most developing countries had high tariff walls before 1995

Note: Based on World Bank data that I used in my 2016 book, The Great Convergence.

These experiments with Trump-like tariffs failed, but there was a beautiful theory behind them – a theory that is now discredited but was, and still is, compelling in its simplicity. The economic theory behind import substitution industrialization (ISI) was laid down in the mid-20th century by economists like Raúl Prebisch and Hans Singer.

The economic part was quite simple: in a world where demand creates supply, putting up high tariffs shifted domestic demand from imported goods to locally produced goods. The new demand would create new domestic industry. Presto! Iindustrialization is driven by the substitution of imports with domestically made goods. That’s where the name ISI comes from.

There was a political, or grievance, aspect of the theory as well that tended to get many people quite heated about the theory being morale as well as economically justifiable.

Donald Trump claims that the US is victimised by the world trade system. That is exactly how the ‘structuralist’ school viewed the world economy back then (and many still do today). It was rigged against developing nations by colonists. In one version, the rich got richer because the poor got poorer.

To escape this ‘unequalising trade’ trap, the advice of the structuralist development crowd was as simple as Economic Trumpism: stop importing manufactured goods, build them at home behind tariff walls, and industrialization would follow (see Prebisch 1950 or Wallerstein 1974).

My frequent readers will recognise this as the forerunner of Trump’s ‘grievance doctrine’. Immanuel Wallerstein’s world systems theory cast the global economy as an exploitative ‘core–periphery’ structure. The rich, industrialised core supposedly locked the periphery into underdevelopment through colonialism, imperialism, and unequal exchange. The political conclusion was compelling: if the system is rigged, the only way out is to build walls around the national economy and force industrialization by decree.

Why Import Substitution Industrialization Failed

There was nothing wrong with the economic or emotional justification of the high, broad tariffs. The problem is that reality didn’t cooperate.

Of course, the demand-creates-supply did work for some industries, so it seemed to be validated in the early years. ISI worked in bringing ‘light industry’ inside the tariff wall (Balassa 1981, 1985). But when it came to the more sophisticated heavy industry (autos, chemicals, machinery, electronics, etc.), the domestic market wasn’t sufficient to create domestic supply. The tariffs didn’t work.

Only a handful of nations managed to industrialize significantly, and most of those were in East Asia. But they did not rely on indiscriminate tariffs. Instead, they combined targeted protection with export discipline, state-directed credit, and careful government–business coordination. Protection was temporary, conditional, and linked to performance (Amsden 1989).

Consumers paid high prices for low-quality goods. Export performance was dismal or entirely absent. By the 1980s, many countries that had embraced ISI were wondering about the wisdom of following a 1950s-era theory in the age of modern manufacturing.

As Figure 1 shows, there was a near-universal volte-face on tariffs in the 1990s. Why was that?

Globalisation Changed and Turned Protectionism into Destructionism

At the end of the 20th century, industrial protectionism turned into industrial destructionism. For developing nations, the nature of industrialization changed. Instead of keeping tariffs high to keep industrial goods out, they had to lower industrial tariffs so G7 manufacturing firms would include them in their global value chains (GVCs).

With the ICT revolution, production stages no longer fit neatly inside national borders; they stretch across countries. Autos are not made in America; they are made in what I called ‘Factory North America’. Autos are not made in Germany; they are made in ‘Factory Europe’. Autos are not made in Japan; they are made in ‘Factory Asia’. The whole world of manufacturing changed around 1990s.

In my 2016 book, The great convergence: information technology and the New Globalization, I called this ‘globalisation’s second unbundling’. (The first unbundling was goods crossing borders; the second unbundling was factories and G7 manufacturing knowhow crossing borders.) The phenomenon subsequently became known as the ‘Global Value Chain (GVC) Revolution’.

Indeed, it is exactly this change in the nature of globalisation that led the developing nations to abandon broad and high tariff walls.

Economic Trumpism in the 21st Century

That brings us back to 2025. Unlike the developing nations of the 1960s and 1970s, the US is already a fully industrialized, high-income economy. It does not need to ‘force’ industrialization behind tariff walls. Quite the opposite: it relies on global supply chains, advanced services, and integrated capital markets. Walling off the entire goods-producing sector is not just unnecessary, it is counterproductive. The US is in the process of hobbling its own factories, raising prices for its own consumers, and pushing investment and innovation offshore.

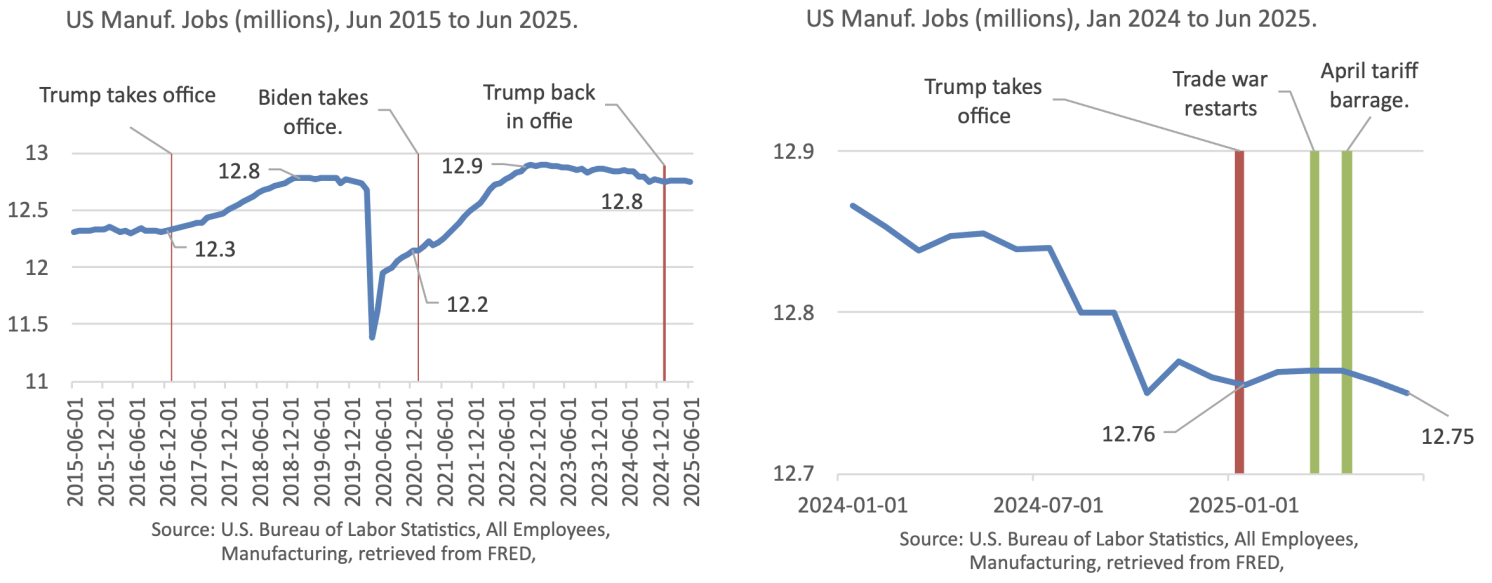

Don’t take my word for it. Look at what has happened to manufacturing employment under the second Trump administration (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 US factory jobs: Down on Trump’s trade war

The basic problem is that a lack of demand is not the constraining factor in American manufacturing; it’s the workforce. The group of workers who are able and willing to work on a factory floor is shrinking. Almost 400,000 manufacturing jobs are currently unfilled, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Conclusion: Tools Vversus Walls, Sectors Versus Nations

The bottom line? Tariffs have always been political, but they usually work as tools to protect favoured sectors. They are narrow, targeted, and often effective in shaping industrial outcomes (even if those outcomes are inefficient).

Trump’s tariffs are different. They aim to wall off the entire economy, reviving an old, discredited development strategy that failed almost everywhere it was tried.

So is ‘Economic Trumpism’ import substitution 2.0? Yes. And my guess is the ISI 2.0 will end the same way ISI 1.0 ended – economic failure and eventual abandonment.

Broad tariff walls don’t build nations. If they build anything at all, they build inefficiencies. In the end, Trump’s tariffs may succeed in mobilising short-run political support, but they will fail to protect American prosperity. As I said in a recent Factful Friday, “Trump won politically, but America lost economically”.

See original post for references

Russia also started building up local food – the most important point of self-sufficiency when you think about it – production capabilities already in 2014 after the Maidan coup so they were not a deer caught in headlights.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/07/russia-retaliates-western-sanctions-ban-food-imports

That article does not mention it but EU countries were visibly shocked when Russia did that and could hardly believe that the Russians would ever do it. It was at this time that the Russians invested in domestic production, as you noted, such as cheese and there were many willing farmers that were onboard with this as they now knew that they did not have to worry any longer about imported EU food stuffs coming into the country to deliberately undercut them. It was humorously noted at the time that Russia’s PMC were flustered by all this and were asking ‘But, but what about our imported French cheeses?’

The Russians happily produce local versions of the beloved French and Italian cheeses.

https://www.rbth.com/travel/tours/food/2017/04/25/french-cuisine-in-a-russian-cowshed_749471

In fact, Italians living in Russia have been showing them how to make them.

https://moscaoggi.ru/formaggi-italiani-dallanima-russa-in-arrivo-a-mosca/

Let’s not forget that the Russians have many of their own great home-grown cheeses, salami, etc. (Caucasus region is famous.) https://www.rbth.com/russian-kitchen/329871-10-russian-cheeses

I must admit that I have a lot of respect for the Russians. They have shown great adaptability in the face of everything thrown at them and they have not buckled. The Collective West has shown itself to be rigid and unimaginative. How will the CW fare as its slow-motion collapse progresses?

The Russian made “Brie” and “Camembert” cheeses used to be absolutely terrible. Rubbery and flavorless! Now they are amazingly good. Seriously. That’s my experience.

Russia bans cultivation and import of GMO food, too. Good on them.

I appreciate this is a short essay on a topic with a vast research literature, but the history of tariff use for developmental aims is far more complex and nuanced than the article allows. There is plenty of evidence that it was not just worked (at least temporarily) for some countries, but that it may well be a vital ‘phase’ for any country which is engaged in catch-up development. As a model, it fell out of favour in the 1980’s and 1990’s largely because most countries had recognised that even if it had worked previously, as a policy it had run out of steam, and could, in any event, only work in the long term in very large economies with internal scale. It also fell victim to the paradox that the countries that successfully followed the model (such as all the early Asian Tigers) had simultaneously tried to run large export surpluses, and you can only do that for so long before your trading partners refuse to accept your tariffs. In many countries (e.g Japan and RoK), rather than drop tariffs they surreptitiously replaced tariffs with more subtle import barriers and many still remain.

Trumps tariff policy is certainly (with the arguable exception of Russia) the only recent example of a highly developed country ‘reversing’ on tariffs and trade, although of course this has happened before (1930’s). But rather than see this as Trump adopting a proven failed past model, I think its more accurate to see this as part of an inevitable cycle in world trade where long term trade imbalances largely created by demand suppression in surplus countries (as anticipated by Keynes) produces a reaction which is built into the system. Trump is a symptom of the problem, not the cause. Some sort of trade war is was pretty much built into the system from the creation of the post war settlement, the only real question has been when and what form it would take. The US, with its highly dysfunctional international policy seems to always the location of whatever trigger sets off a reversal, as (probably), Smoot-Hawley did in 1930.

I’m disappointed this article cheap shotted the Structuralists (Prebisch-Singer) and World Systems Analysts (Wallerstein, etc.), whose views were not identical. Singer’s hypothesis, which I think was more cyclical than secular was that terms of commodity trade declined for what was then called “the third world” and there was a lot of value to that hypothesis. Part of the problem comes from a category of analysis such as “Third World” which lumps a lot of differing countries and regions together in terms of levels of economic development and capacity. Wallerstein’s theory was about a lot more than unequal exchange. It remains to be seen whether or not the integration of the Global South into GVCs really allows them to move up the ladder or just favors a few specific areas such as China. There were certainly problems with ISI. Most stress that outward looking instead of inward looking worked better. But there have been significant problems with the rise of the GVC and structural adjustment era as well. At best, performance has been no better. I think what is unique about Trump’s approach is that he is putting tariffs on old industries, rather than infant industries, which is where historically tariffs were placed whether in 19th century Germany or late 19th century US. Also, the Global South really does have reason to see itself as a victim of the international system, whereas Trump ignores the multiple benefits, in addition to the costs of the US being the world hegemon.

Agree w plutoniumkun and Chip on the broader tariffs arguments.

The bit about job loss at the end is also contradictory and not supported by the evidence. Hasn’t been long enough, and the change not drastic enough to blame reduction in manufacturing jobs on tariffs. And then the argument that its the shrinking workforce is at fault adds a second, unrelated cause of falling jobs. Which is it, tariffs or shrinking workforce? Author’s evidence for a shrinking workforce is also slim – 400k job openings neglects a) jobs may not pay well enough or exist in locations which workers are willing/able to move to b) immigration crackdowns may be a factor, and c) employers routinely inflate number of job openings ( for instance, by keeping job postings up with no intention to hire to signal to investors that the company is expanding).

I agree, the 400k “missing” factory workers is a classic ruse to induce one to ignore the herd of elephants in the room. I am not sitting in the middle of the road watching the turnip truck drive away and wondering how I got here.

Mismanagers complaining about mismanagement is not a solution…

The more apt description may be “Where are we going,and how did I end up in this handbasket?” as it at least acknowledges that we’ve sleep walked our way to the top of the stairs…

Worth remembering that with the rise of automation re-shoring may have little to no effect on employment. I follow Rory Stewart. He recently visited a Chinese port. The only time he saw a human being was on entering and leaving when the guard saluted him. Everything else in the entire port was automated.

I also recently watched a video claiming to show a new Chinese car factory. Not a human in sight, everything being done by robots. Expected production of 400,000 vehicles per year.

I think the future is here, now.

Read somewhere that the sanctions had moved Russia to near-total agricultural independence. (Agriculture would be a good place to start with any carefully directed/applied import substitution push. Many newly-independent countries tried to do just that from the 40-80s, and the West worked hard to keep them dependent, pushing inappropriately-scaled Green Rev. solutions that drove small farmers out of business and–in so doing–squashed many agricultural traditions and foodways, pushing women especially away from growing for nutrition and family.) There’s plenty of dis- and counter-info out there about whether Russia is on the brink of collapse or doing okay or better, thanks, and I don’t see anything to substantiate on a first glance, but it will have boosted production in some farm sectors w o doubt. . . The right to food sovereignty runs deeper than national flags and armed/open hostilities between nations, of course.

The irony in Trump’s approach now–with China proving so much nimbler (as a command economy can afford) is that we are so fully in the Third World/poor country position, and in real decline. The fact that the Republicans and Nixon took the first giant steps to engineer this interdependent little planet, where capital pushed niceties like flag-waving aside to sew American flags in China. . . would be amazing to contemplate, were we not up to our keesters in such ironies already.

Jane Jacobs provides some good elucidation on when and where ISI works, specifically it can only work on the micro-level, or firms and cities, and not really at the macro-level. This paragraph from this article struck out to me the most:

The careful government-business coordination part is what makes it work in the local scope. An example I can think of is the redevelopment of Pittsburgh in the 00s and 10s. The Federal government under the Obama administration provided a heavy investment into NREC in Pittsburgh, but this was also buttressed locally by the RIDC, a Pittsburgh area non-profit dedicated to land remediation and economic development through refurbishing old industrial park and steel mills into usable industrial and office space.

So you had a city that already had a good research base, along with funding and coordination from the federal government, as well as the local land bank supporting local development, and this allowed many self-driving car and robotics companies to come to Pittsburgh, revitalizing or bringing in a lot of secondary support industries such as machine shops and design firms. Manufacturing came back to Pittsburgh, because investment created a strong enough local demand for it where proximity and quick turn around was more important than lowest-cost considerations.

It seems many Republicans and other tariff boosters were too enthralled by Field of Dreams, with a “If you build it, they will come.” attitude where all they have to do is set the correct tariff level, subsidize the construction of some factories, and everything is set. But as the article pointed out, and to remix a common philosophical proposition: if you build a factory, but no-one is there to work or maintain it, does it actually make the stuff you need?

Biden already started to run into this issue with the CHIPS act where there were not enough qualified engineers and technicians to support the hiring levels electronics manufacturers would need in order to staff the facilities they planned to build. With Trump gutting higher level education in the US, this problem is only going to worsen.

local land bank supporting local development, and this allowed many self-driving car and robotics companies to come to Pittsburgh

using the land bank to fund silicon valley pipe dreams is very much obama who also industrialized the insurance industry among others.The industrial policy of the US is break unions and offshore jobs, kick the precariat and this is not a republican policy, its the policy of the entire bought and paid for political class. At this point it is hard to see which party is the lesser evil.

I agree that because of this it will indeed only get worse.

As obama allowed the kingpins who caused the GFC to fix the crisis they created because only they were smart enough to do it parallels todays PMC yearning to be back in charge and inspires carvilles advice to lay down and play dead so they can get back to screwing things up where they left off.

My point was more to illustrate the level of coordination and multiple factors needed to get positive results, not necessarily on the merits of the Obama administration or self-driving cars. Pittsburgh has slumped a bit since Uber sold off ATG and Argo got diced up between Ford and VW, but a lot of those initial investments are still benefiting other start-ups and companies in autonomy and sensor technology in the region. There was also a lot of optimism 15-20 years ago in the power of technology, especially when the 2000s were the pre-enshitiffication stage of the World Wide Web and when Google actually tried to “Do No Evil” so not everyone who followed the bandwagon of supporting Silicon Valley at that time should be faulted for supporting “pipe-dreams.”

However, I do agree with you that the Democrats are just as likely as Republicans to support the neoliberal agenda, even if they at least understand that coordination and funding is needed to get certain development patterns to be undertaken. Obama’s production company acquired and distributed American Factory, a documentary about the on-shoring of a Fuyao tempered glass assembly plant in Dayton, Ohio occupying a former GM plant. The documentary tries to spread blame for the dysfunction from the on-shoring effort between Fuyao and the workers, with the film’s climax focusing on the plant’s unionization efforts. While the film was entertaining for providing a “how the sausage is made” portrayal of the American management staff of the company (incompetent, unable to facilitate work, only decent at toadying to Chinese leadership), there was something that bothered me after watching it.

The film focuses on the people present, and doesn’t provide any background narrative or additional contextual information. This absence was described as being chosen for some aesthetic purposes of the film, but it can trick viewers into thinking politicians are absent from the film because they’re unimportant and didn’t contribute to the comedy of errors in the film. It reinforces the neoliberal idea that politicians are there simply to “Make the right conditions,” instead of the idea that politicians and representatives were derelict in their duties to monitor or delegate the monitoring of the construction and operation of the factory in its initial stages to make sure good outcomes were happening, and be able to course correct if things went wrong.

One possibility that should be noted is that while the tarriffs are unlikely, in the extreme, to reindustrialize the US – particularly by shifting the blame from US oligarchs seeking higher profits to foreigners, they do create vast opportunities to extract wealth from the US economy for favored individuals (e.g., tarriff exemptions and/or not imposing an exemption, with new rules every 90 days or less).

There is a great deal of ruin in an “empire” … lots of meat on those bones.

The article’s most interesting point is how tariffs disappeared as Western supply chains globalized. It’s most annoying to discuss Latin American tariffs and leave them out of the trend plot! Almost like the chief editor of VOX neglected to have someone review his piece.

One consequence in many countries with high average manufacturing tariffs is that this acts as a tax on agriculture and on non-tradable sectors of the economy such as healthcare. That had (and in some countries continues to have) a huge impact on rural poverty (and leads to a dependence on imported food).

That can also be true when a single product faces high tariffs. Two examples.

1. In the case of Japan, the emphasis on self-sufficiency in rice undermined the rest of agriculture: no other crops could provide the same income per hectare, resulting in a rice monoculture, overall high food prices, and a near-total dependence on imports for vegetables, legumes (for example soybeans for tofu) and wheat.

2. In the US, you note the Chicken War tariff but don’t follow up with the impact on trucks of that 1964 “temporary” 25% tariff (which is still in place 60 years later). That lowered the relative profitability of cars (that is, sedans) and was a contributing factor to the US shift away towards vans (some classed for tariff purposes as trucks), SUVs and other light trucks. [In the US, CAFE fuel efficiency rules also favor light trucks, amplifying the Chicken War tariff.]

In contrast, China has a passenger vehicle market 50% larger than that of the US, but pickups are only about 2% of the market, with almost none found in large cities. Europe is similar, though I don’t have data at hand.

Note that in all markets where I have recent first-hand experience (China, Japan, Europe, the Philippines) there’s a shift towards SUVs as family vehicles, but cars on average remain, well, car-sized. But in the US … my wife has a Honda CR-V, which is hard to find in the sea of humongous SUVs and pickups on the rare occasions we head to a city (trips to Costco). That’s not a problem in China, Japan or Europe.

Trump’s tariffs have nothing to do with Import Substitution Industrialization — this is simply his usual salesmanship and misdirection. He is more than happy with how globalization has destroyed organized labor, offshored jobs, and concentrated wealth into the hands of a thousand families.

His real agenda is a return to pre-1913 America and to substitute tariff revenue for income and estate taxes, which it is his stated goal to repeal. His intent is for imports to remain at current levels and to cram tariffs down our throats as a regressive form of Value-Added Tax.

One thing that can be said with certainty is that imposing a 55% tariff on China would be meaningless. Manufacturing wages in China average just one-fifth of those in the U.S. However, if the tariff were 1,000%, many business owners might consider relocating their factories from China to the U.S.

I have a hard time seeing how this construction of ‘ISI’ is not a ginormous strawman. Succinctly, it sets up an ISI model that ‘failed almost everywhere it was tried’. This of course blithely elides over the actual struggles that went on in many of those developing economies: it’s not that import substitution was tried and discarded because it doesn’t work, but rather (at least in my own dysfunctional DE) that it was tried but then brutally rolled back by the élites. The author blames the rollback on tariffs being too blunt of a bludgeon, but for his argument to succeed he needs to skip over all of the other policies that were actually implemented to accompany those tariffs.

To be frank, it really looks like he started from the conclusion that Trump Tariffs Bad and then worked backwards, deciding to lump in all of ‘Latin America by in [sic] the 1970s and 1980s’. Except the wee problem is that those Latin American tariffs (eg, in my DE) were indeed, unlike Trump 2025, accompanied by state industrial planning–‘<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FMA_I.Ae._27_Pulqui_I heavy industry (autos, chemicals, machinery, electronics, etc.)’. The reason why this state planning failed was not the imprecise bludgeon effect of tariffs (as per the article) or a lack of autarky (as per the intro), but rather a failed political battle, in which the oligarchy that benefits from an underdeveloped raw material exporting economy reversed the model by brute force.

Oh and PS, just to be petty because I’m way triggered, the article needs some serious proofreading. ‘Vversus’?!?

Thank you. The absence in this piece of the role played by comprador elites indicates either ignorance on the part of the author (many, if not most in his field have forgotten that it has always been POLITICAL economy, no thanks to the utter domination of the priesthood of neoclassical economic orthodoxy in virtually all university departments in the West) or the mendacity of intentional omission. Either way it is inexcusable.

Thanks for the article, Yves.

Typo in intro: “broad baaed sanctions” should probably be “based”.

I sure would welcome any news stories on America re-industrialization. I go looking for them. I don’t find too many, but here’s one:

Korea Invests $5 Billion to Make American Shipbuilding Great Again

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Fpi7ilb5wQ

Hanwha Places Largest U.S. Commercial Ship Order in Over Two Decades

https://gcaptain.com/hanwha-places-largest-u-s-commercial-ship-order-in-over-two-decades/

So this is an example of American investment by a Korean shipbuilder. I think more business cooperation like this has merit, but I don’t see how this is encouraged by having a tariff policy that seems aimed at penalizing America’s long standing economic trading partners along with the American people. The application of tariffs has to be much more strategic and long term, and I don’t see that happening in the current WH. Nor do I see Congress stepping up to resume it’s proper role of setting tariffs.

Most of Keynes’ work relied on balanced trade where the value exports generally equalled the value of imports. Not just goods but tradeable services as well. The US has run trade deficits for about 50 consecutive years, and has paid for those deficits by selling assets like shares in companies or whole companies, real estate and debt. If we go back to the Keynesian national income equation, when imports are larger than exports then it reduces economic growth. Well real GDP growth is about one-half what it used to be prior to running trade deficits. Some of the loss in assets goes are straight through trade, a foreign company sells to the US and gets paid US cash. Some are through transfer pricing where an American company produces offshore and sells to the US but the paperwork goes through a tax haven which ends up holding much of the profits; these can be applied to purchase US assets.

We often hear that Americans don’t want to manufacture because money can be made in other ways. Then again real economic growth is around 2% and then annual budget deficit is about 6% of GDP, and then there is a trade deficit that runs 2-3% of GDP. The only way to reverse this is by the US selling to the world more than it buys from it. Which means a trade surplus. Trump senses this, but he is not the guy to pull it off. He is too impulsive and reactive and without any long-term vision.