For more than a century, the United States has projected power abroad through naval presence. A cruiser anchored offshore was once enough to send a message: comply or face consequences. The strategy of gunboat diplomacy rested on overwhelming naval superiority, rapid deployment, and the expectation that smaller states would lack the means to resist.

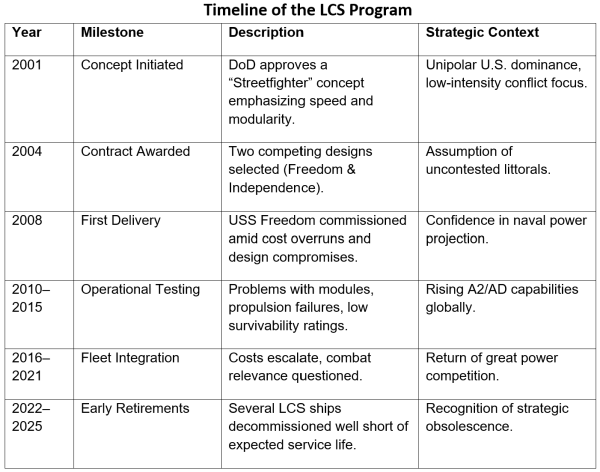

But times have changed. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), conceived in the early 2000s as a sleek, fast instrument of military force in contested littoral waters, is now being quietly retired. Its failure is more than a procurement fiasco. It marks the end of an era in which the U.S. Navy could sail close to another nation’s coast and expect submission rather than defiance. This article explains the convergent failures of the LCS program and the associated coercive diplomacy concept.

A Solution for a Misconceived Mission

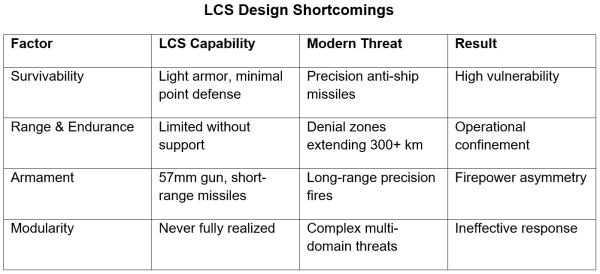

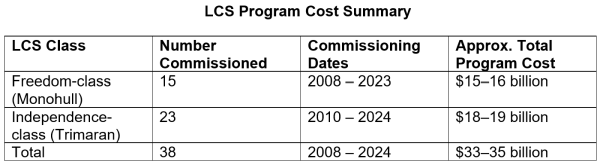

The LCS was intended to fill a perceived operational gap between large surface combatants and smaller patrol craft. It was to project U.S. naval power in the shallow, congested waters of coastal zones where larger ships would be vulnerable, and to do so quickly, flexibly, and with minimal crew. Two distinct classes were developed, Freedom-class and Independence-class, featuring high speeds (40+ knots), modular mission packages, and minimal armament. Unfortunately, this combination proved fatally flawed. The mission modules never matured as promised. Mechanical failures were frequent and costly. Survivability against modern threats was negligible. The ships were too fragile for high-end combat and too expensive for low-end presence.

Freedom class LCS

Independence class LCS

Two Designs, One Program: A Built-In Vulnerability

From its inception, the Littoral Combat Ship program was unusual in that the U.S. Navy approved two entirely different ship designs rather than selecting a single platform. This decision reflected both strategic uncertainty and bureaucratic calculation. Officially, the dual-track approach was framed as a competitive procurement strategy intended to lower costs, encourage innovation, and allow the Navy to “downselect” after real-world testing. The two designs, the Freedom-class littoral combat ship monohull and the Independence-class littoral combat ship trimaran, represented sharply different engineering philosophies.

Beneath this rationale lay deeper currents. The Navy did not have a clear concept of operations for littoral warfare in the early 2000s, so authorizing two designs functioned as a hedge against strategic uncertainty. Political considerations were equally important. Two shipbuilders, Fincantieri Marinette Marine and Austal USA, meant more congressional support, more distributed jobs, and greater resistance to cancellation.

In theory, the Navy planned to select a single design after operational testing. In practice, it never made that choice. Both designs entered serial production, creating a fractured fleet with incompatible maintenance and training pipelines, duplicative logistics chains, and ballooning lifecycle costs. This dual-design structure magnified every other shortcoming of the program and is now widely recognized as one of its original strategic errors.

The Death of Gunboat Diplomacy

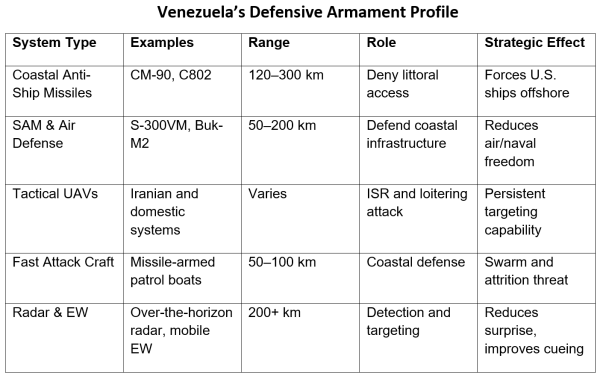

Gunboat diplomacy once worked because great powers had ships capable of threatening coastal states with impunity. But the proliferation of Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) military technology has overturned this dynamic. Land-based systems such as the Chinese-made C-802 anti-ship missile can strike naval targets in the littoral area. Ballistic and cruise anti-ship missiles like DF-21D extend denial zones hundreds of miles offshore. Loitering munitions and UAV swarms provide persistent surveillance and strike capability. Advanced air defense and electronic warfare systems make littoral penetration risky even against states lacking a traditional navy.

The LCS is poorly suited to the modern threat environment. Designed for speed and flexibility, it is lightly armed, minimally protected, and dependent on modules that never delivered promised capabilities. In any contested littoral, such as the Persian Gulf, the South China Sea, or the Caribbean, it would face layered threats from land-based missiles, UAVs, and submarines. This technological shift means deploying a U.S. naval presence is no longer a cheap, low-risk form of coercion; it is an expensive potential liability.

Convergent Failures: Program Development and Foreign Policy Strategy

The Littoral Combat Ship program failed not because of a single misstep, but because of a convergence of flawed procurement practices and outdated foreign policy assumptions. On the procurement side, the program was shaped by a belief that naval power projection would remain largely uncontested in the world’s littorals. The resulting ships prioritized speed, modularity, and cost-efficiency over combat effectiveness, survivability, and lethality. Engineering compromises were made in the expectation that advanced mission modules would offset the lack of organic capability, an expectation that never materialized.

Meanwhile, U.S. foreign policy strategy continued to rely on the logic of gunboat diplomacy, assuming that the visible presence of U.S. warships would translate into political leverage. This strategic posture was formulated in an era of unipolar dominance and persisted even as the global environment shifted. While the Navy was building fragile, specialized vessels optimized for permissive operations, potential adversaries were acquiring advanced Anti-Access/Area Denial systems, precision strike capabilities, and unmanned platforms capable of threatening U.S. surface ships at low cost.

These two failures reinforced one another. A platform poorly designed to enforce an outdated strategy entered service in an era where that strategy no longer worked. As a result, the LCS was not merely a procurement failure; it became a strategic anachronism, emblematic of how procurement dysfunction, institutional inertia, and geopolitical complacency can produce weapon systems that are obsolete the moment they enter service.

Venezuela and the Limits of U.S. Naval Coercion

The Trump administration has been developing a military strategy aimed at toppling the Maduro regime. A hypothetical U.S. naval coercion campaign against Venezuela would have been straightforward in 1990, but not today. Venezuela does not have a blue-water navy capable of challenging the U.S. fleet, but it does not need one. Its arsenal of shore-based missiles, air defenses, and surveillance systems creates a denial zone that would make operations by lightly armed ships like the LCS perilous. Even a large U.S. naval force would encounter significant resistance from Venezuela.

C-802 anti-ship missile

This shift is not unique to Venezuela. Dozens of mid- and small-sized states now possess advanced precision weapons and integrated defense networks. Deterrence, once the preserve of great powers, has been democratized. The assumption that U.S. ships can operate freely off foreign shores is no longer credible. Precision missile proliferation lowers the cost of effective deterrence. Unmanned systems provide surveillance and strike capability without expensive fleets. Electronic warfare and radar coverage erode U.S. advantages in early warning and maneuver. The LCS program failure reflects this new reality: the littoral waters are no longer uncontested.

The Yemen Missile Campaign: Proof of Failed Gunboat Diplomacy

If the Littoral Combat Ship program represents the conceptual failure of gunboat diplomacy, the Yemen missile campaign represents its operational collapse. Since late 2023, U.S. and allied naval forces have maintained a powerful presence in the Red Sea, deploying advanced surface combatants and carrier strike groups to deter and defeat attacks on international shipping. Yet despite overwhelming U.S. firepower, air cover, and persistent surveillance, the Red Sea blockade campaign of the Houthi Ansar Allah military continued largely unabated until the recent Gaza ceasefire.

Yemen is not a great power. It does not field a blue-water navy. Its forces rely primarily on mobile launchers, anti-ship cruise missiles, and UAVs, many of which are inexpensive or supplied through external networks. These weapons, dispersed and concealed, have allowed a weak actor to disrupt global shipping lanes in defiance of the U.S. Navy’s forward presence.

This situation lays bare the new strategic landscape: Naval presence no longer guarantees coercive control. Modern shore-based strike systems can outlast, outmaneuver, and outprice traditional deployments. A single missile battery costs a fraction of a U.S. destroyer and can threaten it just the same. This asymmetry is what gunboat diplomacy cannot survive. The Red Sea campaign has made visible what LCS made inevitable: the age of intimidation by offshore warships is over.

Acknowledging LCS Failure

The U.S. Navy has quietly acknowledged the failure of the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program. Although originally intended to produce a fleet of more than 50 vessels, actual operational utility proved so limited that by the mid-2020s, many of these ships were slated for early retirement—some with fewer than 10 years of service.

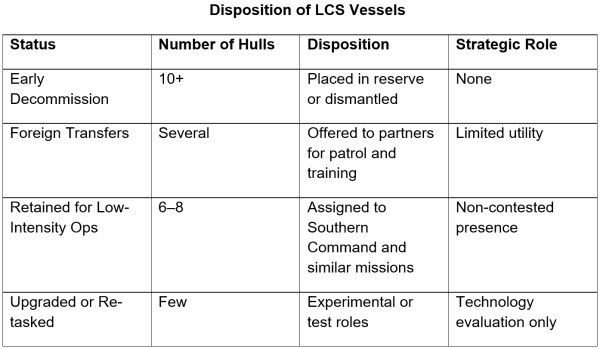

Senior Navy leadership testified before Congress and admitted that the ships could not survive in a contested environment. Budget justification documents shifted resources away from LCS modernization and toward more capable frigate and destroyer programs. Mission modules, once a central innovation, were effectively abandoned after repeated cost overruns and technical failures. The Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan reclassified the majority of LCS hulls as non-combatant or auxiliary assets. Several LCS hulls have been decommissioned early and placed in reserve or used for parts reclamation. Others have been offered to foreign allies for transfer or training purposes. A few are being retained for low-intensity missions such as counter-narcotics patrols in permissive environments.

Conclusion

The LCS is more than a failed warship program. It is a monument to strategic complacency: a vessel designed for a world that no longer exists. The early retirement of LCS ships is an acknowledgment that the era of easy naval coercion is over. Gunboat diplomacy depended on overwhelming, cheap, and credible force projection. That calculus is dead. Precision weaponry has leveled the field. Future U.S. maritime strategy must recognize that naval power projection cannot be taken for granted. The next time a U.S. administration deploys warships to “send a message,” it risks receiving an unpleasant response.

Brings to mind pierre sprey’s observation:

There are two types of marine vessels, submarines and targets.

..and H.Bruce Franklin’s entertaing history of the pursuit of the game-changing wonder weapon, War Stars.

Excellent summation , HH. Next question. Which procurement officers made bank after this CF and moved to the board of a defense contractor?

I think the US Navy should be careful about coming down hard on the people who advocated for and designed these ships. Any kind of research and development program needs to be able to try new things freely and without fear, and it will necessarily get a lot of them wrong. Only people who have never tried to do something new or invent something have the childish belief that you will hit a home run every time. Teaching officers that their careers will be over if they experiment with an idea or a concept and it doesn’t pan out is exactly the wrong message.

A better approach would be to mine the LCS program for lessons learned and new ideas that were interesting and worthwhile. There is bound to be tons of useful new knowledge gained in a long multi-year program like this, and not only would it be smart to capture it and carry it forward, but it would send the valuable message to everyone in the service that good ideas are good ideas, no matter where they come from.

I’m not super hopeful that this will be how things play out in a hidebound organization like the Navy; more likely, people will work hard to deny any association with these programs.

I took a tour of an LCS ship while docked in San Diego, the 1st thing a person noticed was fire extinguishers everywhere, I asked a crewman and they mentioned it was because the whole boat is made out of aluminum for lightness and speed.

Problem is aluminum has a pretty low melt temp and a major fire could melt the hull!

Seemed like a huge vulnerability

Witness the “return” of PT boats courtesy of the Iranian military. This program seems to have coined a newish “military name,” the Boghammer, referring to the original builder of the Iranian fast patrol boats used since the 1980s. It is used to refer to small, very quick and maneuverable patrol boats, generally armed with ship-to-ship missiles. There is your littoral combat boat. I believe that it was the deployment of swarms of these craft by those playing the Iranian team during the infamous Persian Gulf wargame that ended up with the American fleet being sunk on paper.

Missiles and UAVs are the real game changer this time.

This reminds me of the statement that the Professional Military is always planning for the last, previous, war.

The biggest problem from the get go for the LCS was the fact that in order to get to the littoral waters, it had to be able to cross oceans – which is about as anti-littoral as can be. Littoral ship are called littoral because they’re bad in blue water.

Also, multipurpose vessels are for peacetime navies, by default they are too expensive and rare (read: valuable) to be risked in kinetic action. And modular is just a worse version of multipurpose, as one on purpose makes logistics more complicated. As ships usually have deployment times of days or even weeks, but situations chance in hours, you’re likely to have a wrong module on board once you arrive at the area of operations.

As Iranian and Chinese navies have shown, for littoral ships the staying power comes from high speed plus small size (harder to hit), soft-kill systems and great numbers, not heavy armor. The point is that they still can punch way above their weight (weapons per tonnage is much higher).

The math is pretty simple: 3 corvettes can launch a salvo of around 12 to 24 missiles, and be sunk/taken out by 6 to 9 hits. 20 fast attack boats can launch a salvo of 80 missiles and it would take 20 to 35 hits to disable them. Four times more firepower with three times the staying power.

In a way, same logic as two-men assault teams on dirt bikes rather than whole squads in IFVs, no?

Both LCS’s are capable of blue water operations, their main problem is range – they are very thirsty little beasts so without support they cannot stay on station for very long.

Apparently, the unavoidable main issue that arose in wargaming is that they are far too vulnerable to light land based weapons such as anti tank missiles or mid calibre artillery. They simply aren’t robust enough to take the type of beating a standard blue water ship is designed to take. This problem applies to any light and fast littoral vessel. Making them cheap and disposable isn’t really an option as you’ll never make boats as cheap or as disposable as a Kornet or TOW on a technical. So there is an argument that if you want a ship to operate close to shore in the modern world they need to be more like old style monitors – low and heavy, designed to pack a punch and take a lot of punishment (arguably, this is what typical coast guard cutters are designed for). Although its doubtful in todays world if that is really viable or has any utility in most hot environments. There is nothing particularly new in this – as the British found out in the Dardanelles, in a fight between a battleship and a big land mass, the big landmass usually wins.

Of course, the debate about light, fast and cheap vs big, expensive and tough has been going on since the days of the triremes. In the late 1800’s there were plenty of advocates (especially in France) for building torpedo boats and light frigates over battleships as it was assumed that the torpedo was a true battleship-killer. The usual cycles of technology apply. And with the length of modern construction cycles, there is every chance that the question (and answer) has changed by the time you get your new ship of whatever type to sea.

I’m going with the idea that it was not so much an indecisive Navy that decided to build the Little Crappy Ships as the ship builders and their political friends in Congress that push these contracts through. Who cared if they were any good. Think of all the money to be spread all around. The US has sever problems with ship procurement as examples include the LCS, the Zumwalt and the Ford-class aircraft carriers and even with settled designs they find difficulty in building them such as the submarine fleet. Trump may hallucinate about a Golden Fleet but until some of these problems are addressed, it’s not going to happen.

To your point about political friends, I lived in DC when the LCS program commenced. What I remember was frequent drive time radio advertising for the LCS on the classical radio station and, I think, on NPR (although on NPR it wasn’t advertising but “sponsorship”) by, I think, Lockheed-Martin. Which begs the question of the necessity of advertising a new weapon on the radio unless the contractor was trying to build awareness and support for approval. Aside from regularly hearing about the wonders of this new Navy ship was the fact that the ads were read by the radio announcer who consistently mispronounced littoral (he pronounced it “lit-TOR-all”). So I suspect as HH has called it – a defense contractor’s payday.

And didn’t we learn about aluminum ships from the HMS Sheffield in 1982?

lit-TOR-all??!??

Maybe they should have just called it Mulva.

I’ll let myself out now…

It seems to me it would be in China and Russia’s interest, if a proxy, Venezuela, were to use advanced anti-ship missiles to eliminate the US Navy armada off their shores once Trump orders an attack. In fact, this would mirror US actions against Russia via Ukraine.

It’s unclear what the US’s feasible non-nuclear response options are – more ships would be more targets – Venezuela is a big country, and submarines carry limited missiles, and its infeasible that the US military would allow itself to refight a mountainous jungle war.

And Russia likely has provided AAD to shoot down lumbering not-so-stealthy B-2s? Sure, the US is ready to massively refight Desert Storm, but its 35 years later and not a desert.

And now there are reports that the Wagner Group is deploying to Venezuela. Trump approved “covert” actions against the Venezuelan regime as far back as 2016, so, Wagner is probably there to counter the American “hidden” forces.

America cannot even beat Ansar Allah in the Arabian peninsula. Venezuela is orders of magnitude more powerful than Yemen. Also much larger with a greater population.

This looks like a regime change operation that has grown too big for its own good.

Back in the early eighteen hundreds Central and South America fought a series of wars to throw off the yoke of one colonial master, Spain. Why should they sit idly by when a new colonial master, the United States tries to reimpose servitude upon them.

If it comes to formal conflict, we can view the Venezuela versus America War as an anti-colonial one.

Stay safe.

> Trump approved “covert” actions against the Venezuelan regime as far back as 2016 …

Just for the sake of accuracy, Trump was in no position to approve covert or any other governmental actions against anybody until 20 Jan 2017.

> Back in the early eighteen hundreds Central and South America fought a series of wars

> to throw off the yoke of one colonial master, Spain.

Indeed. And I am always impressed that so many Central and South American countries (at least six!) celebrate the same man, Simón Bolívar, as their national hero.

Without getting too hung up on moral sentiments, the situation is indeed broadly analogous, but with one exception: who are Venezuela’s Poland and Romania, that is, the routes through which Chinese and Russian arms to reach Venezuela? Will missiles transit through Colombia and Brazil, say? I don’t think the logistics works. Venezuela strikes me as even more geographically isolated than even the Yemenis. I think they are in this alone.

The other day I heard about one of the major routes going into the Venezuelan capital and it would be a delight for ambush teams. Trump is trying to bluff Venezuela into a quick surrender but if he has to invade, it could be very easily a deadly quagmire they would be hung around the Republicans neck going into next year’s midterms.

Even if Russia/China wished to get so involved and could do so in the time available, there is no realistic route to Venezuela except by sea. Venezuela (foolishly, imo) picked a fight with its eastern neighbour over oil and is not on best terms with Colombia and Brazil (in any event, there are only low grade roads connecting to those countries). Its only direct ally in the region is Cuba, and Cuba has its own problems right now, not least with Melissa on her way.

Back in the 2016 US presidential election I hoped Sanders would win because he appeared the most likely to accept a US imperial defeat, instead of enraged escalation, if and when a minor power sunk an important US ship with missiles. A Gorbachev character, more willing to dismantle the empire if upholding the crumbling empire became incompatible with his domestic agenda. But instead it was straight to Yeltsin, but this time open pillage with empire still standing (and still murderous, even if wobbly).

The example of minor power I used back then was Venezuela. Some things – like being on the US hit list – rarely changes.

Fighting non compliant nations aka terrorists [I feel threatened because you said no too my advances/desires] for yonks has be an excuse to engage the most horrific acts one human can commit on another. The planet was supposed to be pacified for orthodox economic globalism and then it went splat. China and Russia threw a spanner in it all, worst it totally inverted decades of military planing in the West – COIN.

So all the wiz-bang toys that costs heaps [investors overjoyed] to take out brown people becomes a sunk cost. Now prime navel and air assets can be taken out over the curve of the earth. This is not like the past no fly zones in Iraq where air frames patrol to deny national sovereignty in their own air space. This is long arm of denial for such a tactic to be used. Layers of radars, airborne and ground launched missiles deny entry into the zone. Even talk about the best the West has having issues with radar/electrical scanning and information systems going cloudy when bumping into these systems. Chatter about radar being reflected back at the source in air-frames.

Top it off with a big Russian cargo plane was tracked landing in Venezuela of date. Heady times lmmao …

The USAF has the opposite problem in an isolated case…. since the 1980’s it has tried to ground the best close air support aircraft, the A-10, bc it does not have after burners.

Seems they might let it age out.

Well the F-35 fan-bois state that their boy can replace those A-10s and do the same job, no problem…

(crickets)

In the first Gulf “war” the A-10 had two air-to-air kills (both helicopters I believe) and the F-16 (at the time it was the “replacement” for the A-10) had none. The airframe wear and tear is what will finally end the A-10.

Or the fact that there’s no role for a loitering close air support in a war where the enemy has any kind of AA capability. Mig-27 could fly circles around A-10 (quite literally: twice as fast and 60% slower when the need be) and yet pilots were forbidden to fly under 5000 meters in Afghanistan due to Stingers.

Hundreds were retired in the early 1990’s, even when Mig proposed a modernization and lifetime extension package at 1/30 of the price of new Su-34 per plane.

It was the F-16 in those days.

All the budding Steve Canyon’s wanted to strap into that single engine hotrod!

I think it is equitable to argue the USAF has the same problem with the F-22, F-35, and so on. I believe I read the life-cycle cost of the F-35 is in the trillions now?

But you don’t get promoted for killing a program or standing up and pointing out the flaws. You get dismissed, not promoted, etc., and your post-military employment can disappear too.

The best close air support aircraft, the A-10, is so good that USA didn’t even consider sending it to Ukraine. I wish they did, for shits and giggles. :)

Thanks for this article!

But even as an out of date/flawed concept, these ships were not even reliable which may indicate that the MIC has some real problems (as seen in F-35 and other programs).

So here’s more reporting from a couple of years ago, but still relevant:

The Inside Story of How the Navy Spent Billions on the “Little Crappy Ship”

https://www.propublica.org/article/how-navy-spent-billions-littoral-combat-ship

8 Things You Need to Know About the Navy’s Failed Multibillion-Dollar Littoral Combat Ship Program

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5TuEKg48jY

So does all this mean maritime trade can no longer be protected, by anybody for any reason? That any nation (or even sub-national group) that can afford a few radar systems and missiles can deny access to nearby sea-lanes, or put a price on it (“Pay us or we sink your tankers”)? Whatever we think of the fairness of our current international setup, this isn’t a desirable situation.