Yves here. We have regularly amplified the findings of Marianna Mazzucato’s seminal work, The Entrepreneurial State. She documented how the US funded basic research across many universities and fostered creative collaboration with business. That, contrary to ideology, made government, and not the private sector, the leader in innovation by regularly taking risks on fundamental investigation that companies were unable or unwilling to take.

The study below provides a new layer to this general picture. It shows that publicly funded patents that wind up being privately owned are disproportionately productive.

By Andrea Gazzani, Senior Economist Bank Of Italy, Joseba Martinez, Assistant Professor of Economics London Business School, Filippo Natoli, Senior Economist Bank Of Italy, and Paolo Surico, Professor of Economics London Business School. Originally published at VoxEU

The US has long been the world’s innovation powerhouse, based on a system that combines public funding with private initiative. Yet this model is under strain. Using newly digitised US patent data since 1950, this column shows that publicly funded but privately owned patents – just 2% of all US patents – account for around 20% of medium-term fluctuations in productivity and GDP growth. As funding cuts threaten the most productive funders of public R&D, the authors argue that America’s innovation edge rests on the visible hand of public support for basic research.

The US has long been the world’s innovation powerhouse. From semiconductors to the internet, from biotechnology to artificial intelligence, America’s scientific leadership has rested on an ecosystem that combines public funding with private initiative. Yet this model is under strain. Recent debates over proposed budget cuts to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) come at a time when other economies — notably China and the EU — are increasing public investment in frontier technologies. These shifts have reignited a central question: how much of America’s innovation edge depends on public money?

In a new paper (Gazzani et al. 2025), we provide fresh empirical evidence on the macroeconomic impact of the post-war American innovation model — the one first envisioned by Vannevar Bush in Science, the Endless Frontier (1945). Using newly digitised US patent data that distinguish funding sources and ownership structures, we show that government-funded but privately owned patents — just 2% of all patents — account for roughly 20% of medium-term fluctuations in US productivity and GDP growth. These public–private innovations also crowd in private R&D and investment, underscoring the outsized returns to government support for basic research.

Our findings suggest that the US owes much of its technological dynamism not to the invisible hand of the market alone, but to what might be called the visible hand of government-enabled innovation.

The Global Race for Innovation Leadership

The US government’s role in shaping technological progress is often taken for granted. But in the current policy climate, where deficit concerns dominate, public research funding faces renewed scrutiny. The NIH and NSF — central pillars of American science since the 1950s — are under pressure even as China channels massive state resources into artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and green technologies. The EU, too, has expanded its Horizon Europe programme and national innovation funds to address its lagging productivity growth (see Aghion 2024, Bloom et al. 2019).

This is not the first time such a tension has surfaced. As argued by Mazzucato (2013), government agencies have long been the ‘entrepreneurial state’, de-risking the fundamental research that private firms later commercialise. Recent research has examined this theme from various angles — from the macroeconomic effects of public R&D (Fieldhouse and Mertens 2023) to the connection between fiscal policy in a high-debt environment and productivity growth (Fornaro and Wolf 2025). Our work complements this line of research by tracing, at the aggregate level, how different forms of public and private innovation have shaped US productivity dynamics over the past seven decades.

Mapping America’s Innovation Architecture

Following Bush’s blueprint, post-war US innovation has been built on three pillars:

- Government funding for areas of public interest

- Universities and research institutes to conduct fundamental research

- Private firms to commercialise the resulting knowledge.

Using the Government Patent Register database (Gross and Sampat 2025), we classify all US patents granted since 1950 into three groups:

- Public–private (funded by government, owned by a private entity)

- Private–private (fully privately funded and owned)

- Public–public (funded and owned by the government)

We then link these time series to macroeconomic indicators such as total factor productivity (TFP), GDP, R&D expenditure, and investment. By controlling for the business cycle and showing that our innovation measures are not predicted by fiscal and monetary shocks, we isolate the medium-term co-movements between innovation activity and aggregate outcomes.

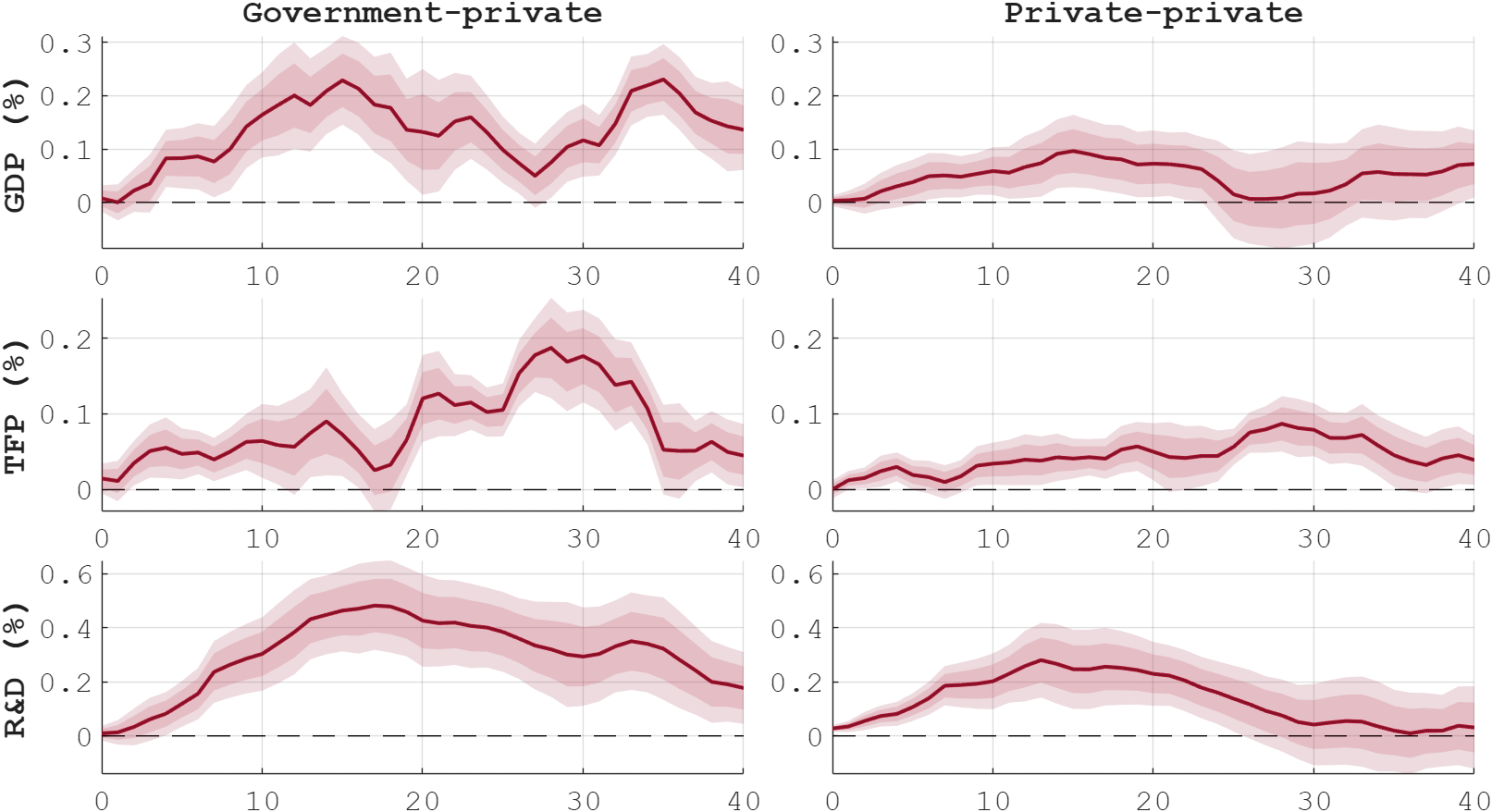

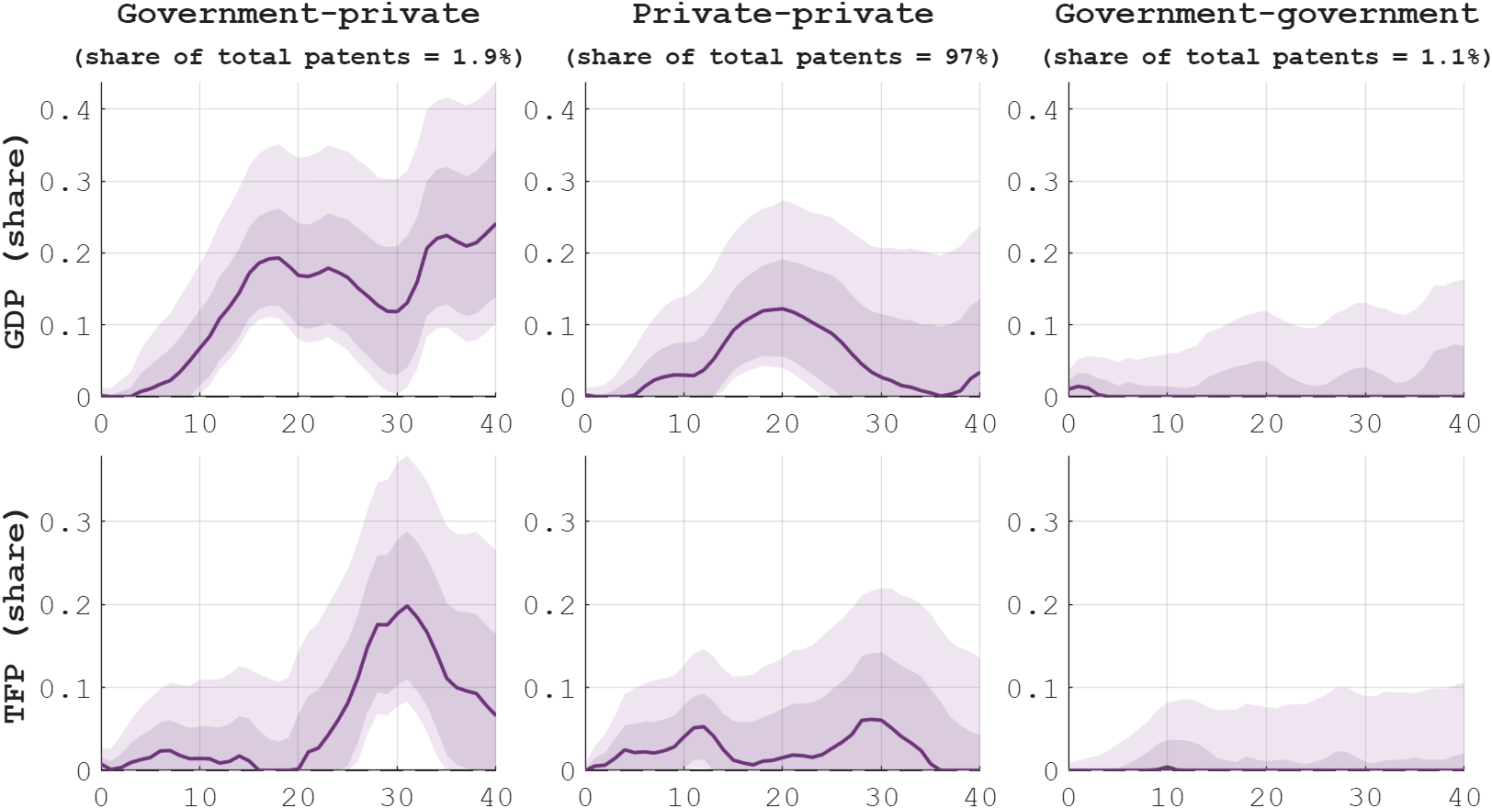

The results are striking. Figure 1 displays the macroeconomic effects of innovation, showing that public-private patents (first column) are characterised by the largest medium-term impact on both output (first row) and productivity (second row), doubling those of private sector innovations over the same horizons (second column). Government-funded but privately owned patents are also associated with sustained increases in private R&D spending, business investment, and real wages. Though public–private patents make up just 2% of the total, they account for about one-fifth of medium-term GDP and TFP fluctuations (Figure 2). Innovation through public–public patents, not shown here, has muted average effects — though it disproportionately features the most disruptive breakthroughs in health and biotechnology. These results hold across ten different econometric approaches, consistently pointing to government-funded research as a key driver of medium-term productivity gains.

Figure 1 Macroeconomic effects of innovation

Notes: The figure displays the dynamic effects of innovation shocks in each category of patents (public-private, private-private, public-public; by column) on (log) real per-capita private GDP and (log) TFP. The estimates are done by means of local projections, where the size of the shock is normalised such as to increase total patents by 1% on impact. Shaded areas report 68% and 90% confidence intervals. Sample: 1950:Q1-2015:Q4.

Figure 2 Contribution of innovation to GDP and TFP

Note: The figure displays the forecast error variance contribution of innovation shocks in two categories of patents (public-private and private-private) on (log) real per-capita GDP expenditure and (log) TFP (by row). Shaded areas report 68% and 90% confidence intervals.

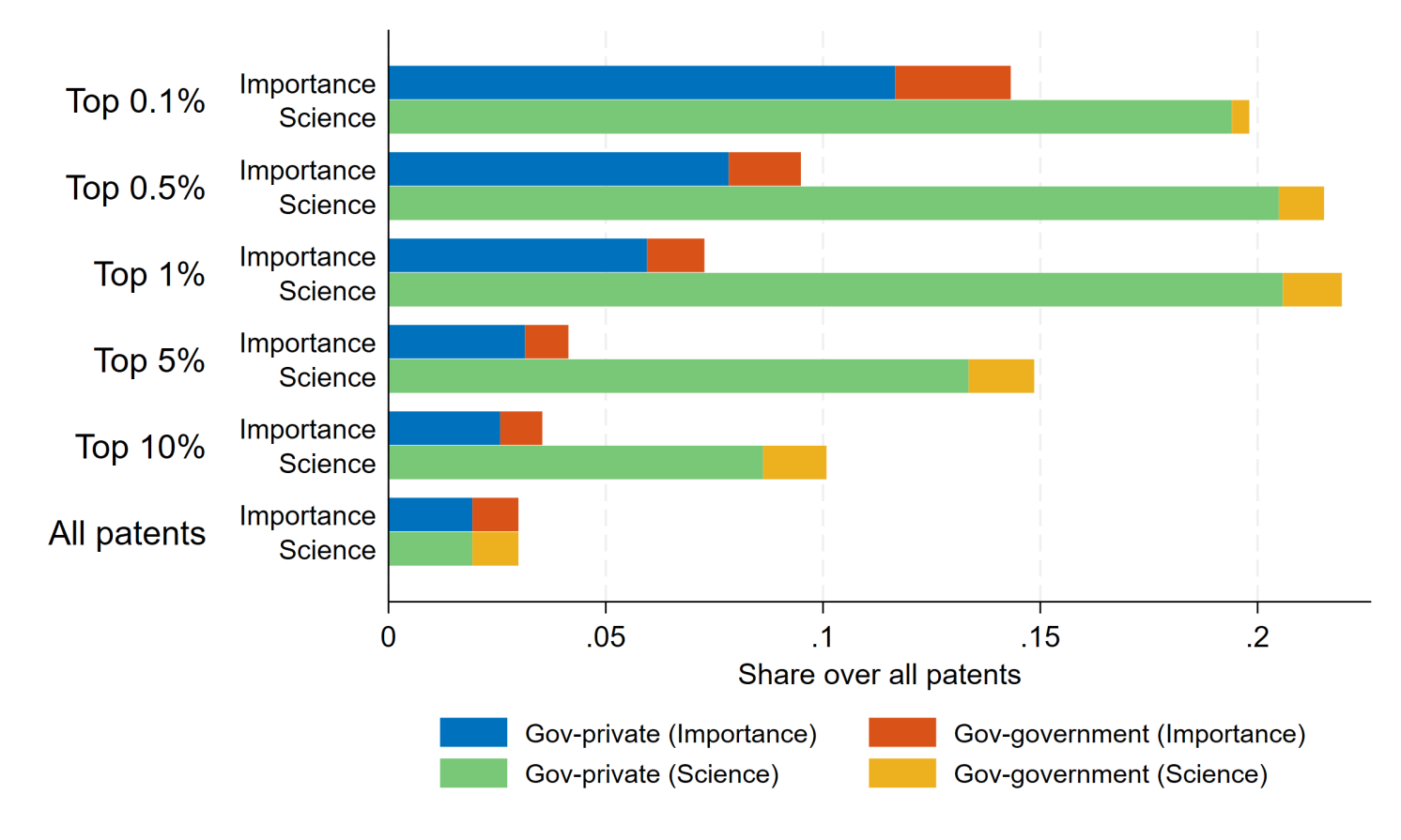

Why are government-funded patents so impactful? Because they tend to be more basic than privately funded ones. Basic research expands the knowledge frontier, generating broadly applicable insights that create powerful spillovers and amplify innovation across the economy. Figure 3 shows that government-funded patents account for a large share of the ‘most basic’ ones, according to measures of basicness based on patents’ similarity to subsequent ones (‘importance’) and on the number of citations to scientific papers (‘reliance on science’). Even though they are far fewer, government-funded patents tend to be much more basic than private ones.

Figure 3 Basicness of publicly funded patents

The Multiplier of Public–Private Innovation

The macroeconomic patterns we uncover echo Vannevar Bush’s post-war vision: the government should fund basic research that private investors find too risky or with too large upfront costs, while universities and firms translate discoveries into applications. This collaboration between public funding and private ownership appears to generate powerful spillovers.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that every dollar of public R&D funding generates between eight and fourteen dollars in cumulative GDP, more than twice the return on privately financed innovation. These multipliers align with recent evidence that public R&D crowds in — rather than crowds out — private innovation (see Bloom et al. 2019, Myers and Lanahan 2022, Bergeaud et al. 2025).

NIH, NSF, and the Geography of Transformative Science

Drilling down by federal agency, the NIH and NSF emerge as the most productive funders of innovation. Patents supported by these two agencies are most strongly linked to medium-term gains in productivity, output, and business-sector R&D. By contrast, patents financed by the Department of Defense or NASA exhibit smaller macroeconomic correlations.

The sectoral composition of innovations sheds further light on why. In health and biotechnology — fields dominated by NIH funding — publicly financed patents outperform private ones by a wide margin. This reflects both the ‘public good’ nature of biomedical research and the long horizon of medical discovery, which private firms may find hard to justify to shareholders. Similar patterns arise in basic energy research, where the Department of Energy’s publicly funded projects have generated significant spillovers into private R&D, consistent with evidence in Myers and Lanahan (2022).

Who Delivers the Biggest Impact?

Beyond federal agencies, the data reveal systematic differences across types of innovators. Research institutes and universities — rather than for-profit companies — produce the most growth-enhancing patents when supported by government funds. When universities rely solely on private funding, however, their macroeconomic impact is roughly half as large.

Among for-profit entities, start-ups and venture-capital-backed firms stand out as more productive engines of innovation than established corporations — but only when they receive public support. Without government funding, their productivity advantage vanishes. These findings suggest that public financing does not displace entrepreneurial activity; it amplifies it.

Such complementarities between public and private sectors echo the arguments made by Aghion et al. (2023) and Mitra et al. (2024) on the design of innovation policy in Europe: when the state takes early-stage risks, the private sector is more likely to scale up transformative technologies. America’s post-war experience offers a textbook example of this dynamic.

The Macroeconomics of Innovation Policy

The aggregate correlations we document are large enough to explain some of the key swings in US productivity growth since the 1950s. Surges in public–private innovation coincide with the ‘prosperous’ 1950s, the ‘roaring’ 1990s, and the productivity slowdown of the 2000s. Had government-funded innovation during the 2000s remained at its 1990s pace, total factor productivity in 2007 would have been 5–10% higher than it actually was.

This underscores an often-overlooked aspect of innovation policy: its macroeconomic externalities. When fiscal tightening or budget cuts reduce public research spending, the impact extends well beyond the lab. It dampens private R&D, slows productivity growth, and ultimately lowers potential output. Conversely, strategic investment in science can serve as a medium-term stabiliser — a finding consistent with the fiscal-growth literature on ‘productive government spending’ (Antolin-Diaz and Surico 2025, Fornaro and Wolf 2025).

Policy Lessons

Our findings point to three key lessons for policymakers:

- Protect public research budgets. Cutting funding for NIH and NSF may deliver short-term savings, but risks undermining the long-run engine of US productivity and global competitiveness.

- Leverage public–private complementarities. The most powerful innovations arise when government funds fundamental research, and private actors translate it into applications. Policy should continue to encourage this division of labour.

- Invest in basic science. Research institutes and universities generate the highest macroeconomic returns per dollar of public support, especially in health, energy, and emerging technologies.

At a time when the US faces mounting competition from state-driven innovation models abroad, the evidence from seven decades of data is unambiguous: America’s technological leadership is itself a public achievement. As Vannevar Bush warned in 1945, “Industry will rise to the challenge of applying new knowledge — but basic research is essentially non-commercial in nature. It will not receive the attention it requires if left to industry.”

Authors’ note: This column does not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy or the European System of Central Banks.

See original post for references

File this under “No shit, Sherlock!”

The cutbacks and the uncertainty in the cutbacks are both issues. I’m on an NSF panel in a few weeks, since the shutdown is over we can actually meet to rank proposals. But who knows if 0, 1, 2, or 3 of those proposals are going to be funded.

Separately , we, and I presume most other departments, don’t know how many graduate students we should admit next year.

The Construction Physics blog has talked about how private entities and most especially Bell Labs were once the drivers of innovation and are now mostly gone. But Bell Labs was itself a kind of public/private partnerships since the ATT monopoly gave them guaranteed profits to support it.

Re the above perhaps the reason “productivity” soars in the medical and pharma realm is because these too are a too big to fail and a highly lobbied and supported part of the economy. Bell Labs by contrast invented things that would have to be manufactured–something that less and less interests our all IP all the time elites. Much easier to make pills and even medicines like biologics are not heavy industrial I would assume.

Lends credence to the lie around the:

The Bayh–Dole Act or Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act (Pub. L. 96-517, December 12, 1980)

which set the tracks for the train to eventually lead publicly funded research to now be employed for private profit, patent speculation and other financial and corporate consolidations – weather or not it actually proves benefit or affordable to the public.

At that time Mrs Thatcher and Mr Reagan didn’t care that their TINA views that knowingly led directly to neoliberalism and the huge inequalities favoring the gifting of huge government resources from the public to the elite finacial sectors of the ‘free market’ through regulatory capture, tax favoritism and blowing asset bubbles and speculative markets unhinged; what they did care about was TINA created an excuse for their own failures and own self interests –

In his Inaugural Address on January 20, 1981, Reagan’s exact words were:

“In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

So – that easily leads to this huge corrupting influence of money into the heart of legislation and that would of course lead to both parties using the crutch of neoliberalism /”free markets” to cure all what ails.

Of course your going to have bipartisan support for someone like B Clinton going along with deregulation and TINA afterall

“National Economic Council. The NEC was established in 1993 by executive” (Bill Clinton) “order” “Those who have served in the role have ranged from former CEOs of the nation’s largest investment firms to financial-services industry managers to seasoned congressional staffers who have managed the economic policy issues for top financial and tax-writing committees.”

Its no wonder the FIRE sector profiteers /predatory wealth is in the saddle in the United States. They stay their because of the weakness of progressive economics.