The Falklands War saved Margaret Thatcher’s career. Donald Trump appears to believe it could save his. This article explores the historical parallels between the political motivations surrounding the 1982 Falklands war and Trump’s current menacing conduct toward Venezuela. Securing a swift military victory in the Falklands to reverse declining political fortunes was a goal achieved by Margaret Thatcher in 1982, but this feat is unlikely to be repeated by Trump in Venezuela.

Thatcher’s Triumph

In the spring of 1982, Margaret Thatcher was a dead Prime Minister walking. Her approval rating had sunk toward 25 percent, lower than any modern prime minister had ever survived. Britain was mired in recession; unemployment had crossed three million; and even her own party whispered about removing her before she led them to annihilation. The “Iron Lady” was rapidly turning into an electoral liability. Many Conservatives believed she would be a one-term footnote, remembered only for austerity, riots, and industrial collapse.

Then Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. The effect on British politics was instantaneous. A failing leader suddenly received a great political gift: an external crisis that appears both morally clear and militarily winnable. Within a week, the British public rallied around Thatcher. Within two months she had transformed from the most unpopular prime minister in living memory into a war leader with heroic approval numbers. And within a year she would win one of the largest electoral landslides in British history. This is the “Falklands Effect,” the political miracle of a short, victorious, foreign conflict. It is also the political fantasy Donald Trump has never quite abandoned.

Thatcher congratulates the victors

The Argentine Junta’s Gambit

But the Falklands story has a second half, usually forgotten in American retellings. The war did not begin because Thatcher was in trouble; it began because the Argentine junta was in political peril. General Leopoldo Galtieri’s military regime was collapsing under the weight of economic catastrophe, human-rights abuses, and popular revolt. Inflation was spiraling. Industrial output had collapsed. Hundreds of thousands marched in Buenos Aires demanding democracy.

The junta needed an escape hatch, a way to convert domestic fury into patriotic unity. So the junta gambled. It seized a remote archipelago in the South Atlantic on the assumption that Britain would do nothing. The military dictatorship initiated a foreign-policy crisis to save itself. And Thatcher, through skill, luck, or historical momentum, converted that same crisis into a political resurrection.

This dual structure is essential to understanding the Falklands War, and it is essential to understanding Donald Trump’s repeated temptation to “do something about Venezuela.” Trump did not merely covet Thatcher’s triumphant outcome; he was attracted to the Argentine junta’s initiating logic. He exhibits both the desperation of Galtieri and the political narcissism of Thatcher. In the Falklands, he sees a two-stage model of political salvation: create a crisis, then win it.

Trump’s First Venezuela Temptation

Trump’s interest in invading Venezuela during his first term is not a rumor; it is one of the best-documented foreign-policy impulses of his presidency. Beginning in 2017 and escalating through 2019, Trump pressed his advisors regarding military action against Venezuela. As the Associated Press reported in 2018, Trump repeatedly asked his national-security team, “Why can’t the U.S. just simply invade the troubled country?” He returned to the subject so frequently that advisers began pre-emptively preparing talking points explaining why an invasion would be catastrophically foolish. John Kelly, then Chief of Staff, reportedly had to walk Trump back from the idea on multiple occasions.

John Bolton’s infamous legal pad note—“5,000 troops to Colombia”—was not a doodle. It was part of a broader, multi-agency evaluation of military options ranging from naval blockades to targeted strikes to full-scale regime-change operations. Trump was reportedly convinced the Venezuelan military would collapse “in a weekend.” He told aides that the Venezuelan people would “welcome us” and that Maduro’s overthrow would be “the easiest win you ever saw.” When he floated the idea to Latin American leaders, they were stunned into horrified silence.

Why this fixation? The answer lies in the duality revealed by the Falklands. Like the junta in 1982, Trump was besieged by domestic scandals, creeping economic unease, and increasingly poor approval ratings. Like Thatcher in 1982, he craved a political transformation—a defining moment of national glory that would override the failings of his administration. A quick foreign war victory could achieve this.

The Falklands pattern is seductive because it promises something no domestic policy can deliver: instant legitimacy and popular support. While Trump’s first-term ambition for a Venezuelan intervention faded under military resistance and political cost, signs of a revived temptation are accumulating rapidly. The evidence of a possible crisis is growing through deployments, proxies, and legal pretexts.

The Current U.S. Military Buildup in the Caribbean

The United States has assembled a large naval, intelligence, and surveillance presence in the Caribbean Basin, officially justified as part of “expanded anti-narcotics operations.” A telling sign of escalation came in November 2025, when the U.S. deployed the Gerald R. Ford carrier strike group to the Caribbean, creating the largest U.S. naval presence in the region in decades. An aircraft carrier strike group is not a patrol asset; it is a warfighting instrument capable of airstrikes, amphibious support, and sustained offensive operations. U.S. specialized Southern Command detachments are embedded with partner forces around Venezuela’s maritime approaches. None of these assets announce themselves as “invasion forces,” and none need to. A military presence justified for drug interdiction can be repurposed overnight if a president wants it to be something else.

Enter Machado

Then there is the political front. María Corina Machado, the Venezuelan opposition figure barred from running by the Maduro regime, has become the de facto U.S.-aligned proxy for representing “true Venezuelan democracy.” Her narrative is amplified across U.S. diplomatic channels and Western media ecosystems. With Machado positioned as the legitimate face of Venezuelan democracy, Washington has an in-place justification for “defending” the will of the Venezuelan people should a confrontation escalate. In 1982, Thatcher wrapped her war in the language of defending “our people” and “our way of life.” In 2025, the language of intervention has been modernized: support for an exiled democratic leader, restoration of constitutional order, protection of human rights. While Machado does not openly call for foreign intervention, her international support network allows Washington to frame her as the legitimate democratic alternative to Maduro.

Maria Machado – Next President of Venezuela?

The Anti-Narcotics Pretext

Overlaying it all is the anti-narcotics legal frame. The U.S. has already indicted Venezuelan officials on narcotrafficking charges and labeled the Maduro government a “narco-state.” Once you define a foreign government as an organized criminal syndicate, the distance between seizing cocaine shipments and seizing oil terminals becomes very small. A naval blockade becomes an “interdiction operation.” A missile strike becomes a “counter-cartel action.” A regional military buildup becomes “drug enforcement staging.” The lawyers call it expanded rules of engagement. History calls it a pretext.

The Falklands Effect

This evolving conflict enabling arrangement, military, political, and legal, matches the structure of the Falklands crisis very closely. Not because a war is inevitable, but because the temptation is resurfacing in circumstances very similar to 1982. Trump has the means, the motive, and the opportunity to use the “Falklands Effect” to restore his political fortunes. The Falklands Effect operates in these stages:

- A weakened leader seeks political revival through external military confrontation.

- Military advisers or political allies propose “limited,” “surgical,” or “low-cost” options.

- The leader launches an armed conflict against a vulnerable nation or group.

- A quick victory restores the popularity and political power of the leader

Resort to this pattern of achieving a quick military victory to accomplish political resurrection is the temptation of diversionary war. But in the case of Venezuela, its consequences are potentially catastrophic.

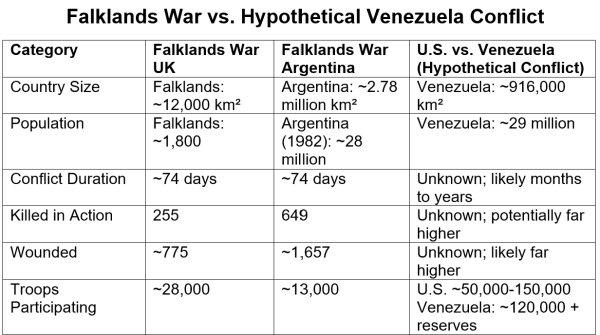

Venezuela Is Not the Falklands

Venezuela is not an isolated archipelago with 1,800 residents. It is a nation of 29 million, with one of the world’s largest proven oil reserves, a large military seasoned by years of internal conflict and sanctions pressure, and a network of allies that includes Cuba, Russia, and China. Its armed forces include an estimated 120,000 active personnel and significant reserves. Venezuela’s vast geography of 916,000 square kilometers includes dense cities, jungles, and mountains, the worst possible terrain for any “quick” military action. Its political culture is one of nationalist resistance. Its population has endured two decades of sanctions and economic isolation. There would be no easy occupation, no quick surrender, and no ten-week victory.

A U.S. invasion or even a “limited” set of precision strikes could trigger a refugee crisis larger than anything in the Western Hemisphere since the Colombian conflict. Oil markets would convulse. Guerrilla warfare would ignite. Regional governments, already wary and resentful of U.S. power, would be forced to respond. Russian advisers stationed in Venezuela might be targeted or killed. Chinese energy assets might be threatened. The local and global escalation possibilities are greater than anything Thatcher faced in 1982.

The Falklands war was a fluke of history: a dying Argentine dictatorship miscalculated, and a faltering British government turned the resulting conflict to its benefit. It was a rare instance where diversionary war did not turn into disaster. It is highly unlikely that the Falklands Effect would be repeated in a U.S. war against Venezuela.

War and Technological Surprise

In modern warfare, uncertainty is magnified by the introduction of new forms of advanced weaponry. The Falklands War demonstrated how a single unexpected technology can destabilize an entire military campaign. The Exocet missile, of which Argentina possessed only a handful, delivered a strategic shock far out of proportion to its numbers—sinking major British ships, crippling logistics, and forcing the Royal Navy into defensive contortions. What unnerved planners was not the scale of the threat, but the surprise: a weapon system whose lethality had been underestimated suddenly proved capable of altering the balance of the war. Had Argentina possessed even a dozen more Exocets, the British campaign could have failed.

A U.S. conflict with Venezuela risks a parallel form of technological surprise, this time from drones rather than missiles. Venezuela has assembled a patchwork fleet of Iranian-designed loitering munitions and improvised explosive drones adapted for swarm attacks. Venezuela also fields modern anti-ship weapons comparable to the Exocet, including the Chinese C-802 family and shore-based missile batteries capable of threatening attacking naval forces. Even if some of these systems suffer from poor readiness or partial integration, a limited number of functioning Venezuelan drones or anti-ship missiles could inflict disproportionate damage, repeating the Falklands lesson that an unexpected adversary capability can impose strategic costs that far exceed its size.

Conclusion

The United States now has the force posture, the political narrative, and the legal pretext to escalate a confrontation with Venezuela faster than at any time since 2019. Trump governs with fewer internal restraints, fewer dissenting advisers, and a party apparatus that treats his impulses as policy rather than improvisation. The danger is real: the Falklands War restored the power of a British prime minister, but applying the Falklands playbook to Venezuela could destabilize the Trump administration, unravel regional security across the Western Hemisphere, ignite a refugee crisis, and provoke great-power confrontation. The parallels matter because millions of lives, regional stability, and global markets could be affected by a decision taken for domestic political expediency. An impulsive attempt to invoke the Falklands Effect in Venezuela could become a political and humanitarian disaster.

This all reminds me of the classic movie Wag The Dog (1997).

I appreciate the parallels with the Falkland War, but our current situation feels more like Bush in 2001 to me, where he started an unwinnable war in Afghanistan to save his career. The conflict doesn’t have to be brief to be effective, unfortunately.

This presumes Trump is a student of history, no?

Trump is old enough to remember the Falklands War as “news” rather than history.

I suspect most of us are old enough to have heard it as news.

The Falklands Campaign is responsible for the first and probably the last newsflash I will ever see in my life. I was seven, in the first year of prep school, and a hyperactive motormouth child like the rest of my form. We were having one of those science lessons where we occasionally watched a schools programme on (gasp!) television. Very exciting! I remember being in the big assembly room, sat in rows turned to face the big CRT television on the side, crosslegged in my shorts, cold lino on my calves. The useless bumbling science teacher Mr V (who also taught RS, stood as a Liberal candidate and could not keep control) turned the television on at the appointee time and then, bam! “We interrupt this broadcast for an urgent news announcement” General Galtieri, Falklands, yadayada. This was of course of no interest to us, except that it clearly delayed the lesson, so we all started talking at once. And Mr V, for the first and only time in my experience, managed a sufficiently stentorian roar to quieten us so he could hear what was, in retrospect, historic news.

Of course, the same year saw the start of breakfast television which quickly became rolling news and then CNN arrived with satellite television and the end of three channel, 9am to 11pm broadcasting and that was the end of newsflashes in the UK.

The Falklands War also resulted in the death of English military aviation, in the form of the Avro Vulcan nuclear bomber.

The Vulcan was a disaster. The first model crashed on its maiden flight, killing all on board. Numerous fatal crashes followed. Sometimes the pilots were able to eject. Crewmembers in the back were always killed.

For Thatcher’s war, three Vulcans were fitted with conventional bombs. Only one made it as far as the Falklands. One fell apart in midair, and was forced to dump its ordnance and make an emergency landing in Brasil, where the authorities impounded it.

That was the end of the Vulcan bomber.

Perhaps the reason that the troubled US F35 fighter has not been used over Ukraine is that the Americans are terrified it will be shot down.

Well, the USS Gerald Ford has a flight deck littered with F35s. We shall see what happens to them if the Peace President goes to war with Venezuela.

Good looking plane, though.

IIRC correctly, in the third Bond movie THUNDERBALL the nuclear bomber that’s crashed underseas and provides the macguffin for the battle between opposed battalions of frogmen was a Vulcan.

As for F-35s in Ukraine, you’re right.

Yes! I saw Thunderball first-run on the big screen. The water landing of the hijacked Vulcan made a lasting impression. The Avro Vulcan was used for the “Black Buck” long-range bombing during the Falklands War, refueled in flight by the Handley-Page Victor. Those wild-looking Cold War bombers seemed like objects out of a Gerry Anderson Supermarionation show.

The Argentine junta only had a handful of Exocet missiles — British Intelligence worked overtime to make sure that they couldn’t acquire more. They were also limited by needing aerial reconnaissance, not having access to satellite eyes. If they had, they might have sunk or disabled the carriers Hermes and Invincible and the ocean liners serving as troop ships QE2 and Canberra, which would have been both a literal and a PR disaster for the British.

I think that the Gerald R Ford is a sitting duck for the technology available to the Venezuelans. Talk about PR disasters…

One of my fave Bond flicks because of the Vulcan! Magnificent looking aircraft!

Going by memory here but I believe that one Vulcan raid dropped about 63 bombs and only one or two hit the runway they were aiming for.

BTW, Thunderball was the fourth Bond film, following Frum Russia With Love, Dr. No, and Goldfinger.

After being dragged into the obviously Bond-inspired power/money/sex fantasy trips of Epstein, Trump, Clinton, et al. part of me wishes that they had never been made…

Thanks HH. I had forgotten the fixation with VNZ in Trump 1.0

Borges, “The Falkland thing was a fight between two bald me over a comb.”

The UK could have failed and as you point out at the end nearly did. Had it, the US was still there to pick up the geopolitical pieces.

This could be a “Suez” moment for the entire West after 500 years of conquest and warlordism.

Always expect Borges, a dyed-in-the-wool reactionary, to come up with a smart ass quip that leaves him smugly above the rest of us.

On a different note: good article! :-)

The Falkland campaign was extremely close.

According to the British briefing given to Australia after the campaign, the Brits were one week away from losing their supply capability. They had 100 ships in their supply chain, and they couldn’t find more.

The Harriers were marginal. The only reason they worked at all is because the Argie air force was operating at the extreme end of their range, and the Brit Harriers just had to pop up and say hi, and the Argies were forced to terminate their missions. If they’d had refueling or longer range, the Harriers would have been swatted like flies and the landing would have been disrupted totally.

One thing that saved British bacon was that Galtieri put reserve soldiers onto the Falklands and kept the regulars back on the mainland in case there was any domestic trouble. This cost them dearly as the British highly trained paras were able to make mincemeat of the poorly trained, poorly led, poorly fed reserves. As seen at Goose Green where 1 Brit para battalion was able to defeat 3 Argentinian battalions dug in in defensive positions – an unheard of ratio.

Excuse my non-sequitur, but wasn’t former Prince Andrew the ‘hero’

of the battle by flying his helicopter just above the ship to decoy Argentine

missiles away from the vessel?

Yes. I do not remember the details but the current Andrew Mountbatten Windsor was a legitimate hero to his fellow British soldiers, sailors, airmen, and citizens. If he had been killed in battle he would have shamed all the rest of NATO, won a posthumous Victoria Cross or equivalent, and would be the shining light of English courage and fortitude today. Instead, he is on the King’s dole and plays video games to pass the time. Pity.

One quibble. Machado does indeed explicitly call for foreign military intervention. Loudly and repeatedly.

The always reliable ‘support the troops’ crowd is a huge temptation

the part about venezuela’s aliies…especially Russia and China…is the part i never see really taken up and scrutinised.

i mean, ever since Trump 1.0, and his trade war with China…i drove by walmart up the road, and thought: they could just blockade us, and it would be over in a week.

if blundering/hubristic us takes out one of China’s oil platforms in that big venezuelan lake…or even stupider things…what would China’s reaction be?

it seems established that they do not need our markets any more.

and theyve been offloading treasuries, etc for years.

whats in the asymmetrical non-kinetic toolbox?

USA doesnt appear to have much strategic depth in much of anything these days, after all.

save the nukes…but theres been recent things regarding those, too…that nobody knows if they even work, since theyr older than i am,lol.

and all of the above ruminations are regarding China acting alone.

is there a bridge too far with USA actions that would unleash the spirit of bandung in response, and…idk…cut us off?

I have hesitations regarding some of the assessments in this presentation.

1. Regarding the geography:

“Venezuela is […] a nation of 29 million. […] Venezuela’s vast geography of 916,000 square kilometers includes dense cities, jungles, and mountains, the worst possible terrain for any “quick” military action.”

The majority of the population (about 19 m) is found on the Northern coast, in the “useful” part of the country representing 250’373 sq km. If there is an intervention, that is where the USA will strike — not in the mountains, the Llano, or the Amazon, for which the expeditionary force has no suitable troops nor equipment.

2. Regarding the military:

“a large military seasoned by years of internal conflict and sanctions pressure”

Internal conflicts do not prepare a military to fight a full-scale war against another powerful military. Besides, years of sanctions pressure imply that the Venezuelan military is probably in a dilapidated state, with not enough modern equipment in good working conditions, and therefore a lack of training with it. Saddam Hussein’s army had been similarly seasoned by years of internal conflict and sanctions pressure — and could only oppose a weak opposition to the offensive ordered by Bush II.

When it comes to guerrilla warfare, then things look differently — although the question will be one of getting resupplied with arms and ammunition. Colombia and Guyana would definitely oppose it, and I doubt Brazil would be of much help.

3. Regarding allies:

“a network of allies that includes Cuba, Russia, and China”

Cuba is in dire economic straits, and I doubt it has any military card to play. China is traditionally wary of conflictual entanglements in foreign countries. After its experience in Syria, Russia is probably not enthusing about coming to the help of an embattled friendly regime. Besides, China and Russia are very far from Venezuela. China and Russia can deliver best-in-class weaponry, but the more complex one (aircraft, AA systems, missiles, ships) require a lot of time to train with it, substantial effort to integrate properly in existing organizations and C3I, and some serious work to elaborate suitable tactics. If such weaponry has not been delivered one year ago, then I contend it comes too late to make a real difference.

Drones are easier, but it will not be enough. Ansarallah achieved impressive results against the USA and its European allies because, in addition to drones, it relied upon a range of missiles, AA defense systems, and vessels. And the Yemenis had years of experience fighting against a coalition of militaries (esp. UAE and Saudi Arabia) equipped with modern equipment — if often ineptly led, even when propped up by Western powers.

My guess is that “strategic” targets in Northern part of Venezuela will take a massive pounding. I do not know how effectively the Venezuelan military can retaliate, but I suspect inflicting significant damage to the forces from the USA will depend on sheer luck (or sheer incompetence by the Southern Spear command). What the USA cannot achieve, and will probably not even attempt, is the folly of disembarking and occupying any substantial part of the country for any substantial length of time. If, contrarily to what Trump hopes, the Venezuelan military endures the blows but does not turn against Maduro, this will leave the expeditionary force depleted of ordnance without much to show for the fireworks, Ms Machado without a perspective, and Trump without the much-needed victory. And then?

Venezuela has been buying Russian weapons for about 20 years now. The rumor is that the Su-30’s build for Iran actually were delivered to Venezuela, so the Bolivarian Air Force may have between 21 to 33 Sukhois. The Venezuelan F-16s were supposed to be already in the crap heap, but apparently Israel (of the MIGA fame) has restored and updated (i.e. to use Python missiles) a bunch of them.

Russians have already said they have delivered Pantsirs to protect the S-300 and Buk M2 systems Venezuela has had for a long time. Russia has also officially stated that they will help Venezuela if Venezuela asks for help. China has condemned US actions towards Venezuela and has many “non-kinetic” ways to express it’s displeasure to the Trump regime.

Oh, and Venezuela has licensed Iranian drones for domestic manufacturing some years ago.

All and all, it seems that Venezuelans are much better prepared than Houthis and may be more willing to fight than the Iraqis.

I think we’ll find out soon enough, Trump just can’t maintain that kind of troop concentration in the premises and not do something soon – be it a bombardment or chickening out.

Regarding the Geography: well, Caracas, main objective here, is surrounded by mountains. Not high, but not easily accessible. My guess is that the gringos will send missiles or throw bombs in what they consider their strategic objectives in Caracas trying to decapitate Maduro’s regime. There is a small airport in the midst of the city though I believe it is only usable by small planes. Maiquetía international airport is in the coast about 70 km away on a highway that goes upwards and upwards to Caracas and can be easily sabotaged.

Any British government that did not at least try to reclaim the Falklands would have been thrown out. I still remember listening to the Commons debate the day after the invasion (a Saturday). It almost turned into a riot. Thatcher had no choice, any more than any other British PM would have. The entire Argentine plan was based on the idea that, even if the British wanted to, they could not mount an operation to recover the islands, and they would have been right if they had waited a year or two, while Thatcher’s defence cuts started to bite, and had it not been for the logistic base at Ascension Island on which virtually everything finally depended. Whether Trump seriously expects to emulate the Argentinian Junta I can’t say: the situations aren’t really comparable, after all, since the regime in Buenos Aires was there because of a military coup.

But the “Falklands bounce” was short-lived. Thatcher would have lost the 1983 election if the Labour Party had not decided to commit suicide and split into two. The Tories lost votes in 1983 compared to 1979 but they faced a divided opposition.

Incidentally, the “Black Buck” Vulcan missions were successful as psychological warfare, even if it was known in advance that the practical results would be small. The missions were extremely complex and involved aircraft refuelling each other several times. Of the seven missions planned, five were carried through to completion, and I think these are still the longest-range bombing missions in history.

Well, kudos to those long-range Vulcans! Strange they were never used again.

Regarding the parliamentary debate, it was merely performative, as the Tories’ backers and the Murdoch press had already decided on war.

Whereas almost no person outside of Florida or my own lunatic Senator Graham wants Trump to invade Venezuela.

And I feel certain that he will not.

Grenada is still there for a do over however.

Thanks for the good article though.

Actually, probably only a month. Both carriers were slated to go the very next month. Hermes to be scrapped, and Invincible sold and sailing to Australia, and to be renamed HMAS Australia if I recall correctly. Australian government realised that it had made a mistake in purchasing the carrier (1 carrier doesn’t work, 3 are needed), and very quickly offered to cancel the deal.

The extremely odd thing was that the end of the British carrier force was widely known in military circles and the Argentinian military attache in London would have known it solidly. Why Galtieri didn’t wait another month is a military mystery, but the 5th of May is Argentinia’s big military day, and the recovery of the Malvinas had been promised for that day. What a lesson!

Yes, I believe that is true. And in that case it was Argentina the country making the first move. I remember that Spanish populaces spontaneously sided with Argentina at that time.

The Venezuela thing is a very different thing. It is a show of strength (or ability to abuse, we will see how it works) by the empire. I am very curious about how an outlet like El País (profoundly anti-Chavez and anti-Maduro) will react to whatever is done. I think that their preferred outcome would be some “clinical” excise of the Venezuelan Chavista tumour if that is possible. The ideal would be the killing of Maduro and a magical rise of a nobel-prize winner as the new leader of a truly democratic, Western rules compliant Venezuela. I find this quite a difficult operation which could fail at many stages and produce outcomes very different from those pursued. While in the Falklands the strategic outcomes were easily understandable and operatively doable here i don’t see any workable strategy here. This is the sign of the times. Trump is a man with no plan.

I was at a LA Kings game with my dad sometime in 1973, when they announced during the game that a peace treaty had been signed and the Vietnam War was over.

Play stopped for a couple of minutes as the actual crowd of 4,529 (announced crowd 7,479-NHL couldn’t draw to save itself in the City of Angels) broke into wild applause-it was a most unpopular war with many in the audience having somebody in the military in their family-as the draft was over and the last draftees were inducted into the military in December of 1972.

Wars since have been yeah whatever affairs as none of us (the 99% not in the military) have any stake in the action, did anybody you know give 2 shits when we left with our tales between our legs in a hurry out of Kabul, it barely made the news.

Were we to ‘win’ in Venezuela, how would that change things?

Losing could be disastrous as our hegemony would be at dire risk.

Huh? US leaving Afghanistan “barely made the news”???

I recall much gnashing of teeth on all wavelengths (from PBS to FOX) when the Biden Admin announced that it would actually follow through on Trump’s agreement to leave Afghanistan, followed by even more wailing after the (inevitably messy) withdrawal.

OTOH, I don’t recall *anybody* outside the Pundit Class who wasn’t relieved that we left.

‘While Machado does not openly call for foreign intervention’

Actually I have heard Nobel Regime Change Prize winner Machado call for precisely that, even though it would mean the deaths of her fellow countrymen but hey, we are talking money here and Muchado has a chance of cashing in big. She reminded me of those Iraqis twenty years ago that called for their country to be bombed and invaded by the US, simply so that they could cash in and get lucrative leadership positions.

The mix of casual and deep thoughts was kinda perfect.

Oil? Giving Donnie a win? Finally getting rid of annoying … and disobedient … Chavistas? Pleasing Little Marco? Certainly not for that Machado creature. Nope there is no reason at all for launching an aggressive war, which is illegal in international law … but who pays attention. to that … against Venezuela. Come to think of it when did Gaza become a play thing whose future was to be decided by Donnie and Bibi and the guys who run most of the neighborhood? Occupied territory, like the West Bank. International law says Israel and the US and the guys in the neighborhood may not do what they are doing. But who pays attention to international law.

I have it figured out. Just like gangsters Donnie and Bibi say a man with a gun gets what he wants almost all of the time. Well that’s settled.