Yves here. We warned back in the day that Brexit would impose a meaningful growth cost on the UK. The imposition of a hard border created trade frictions and increased costs of doing business with the EU for importers and exporters, as well as adding to consumer charges. Financial firms moved some big ticket jobs to the continent as required by EU regulations. The UK was also no longer part of a large economic bloc, and had to cut its own trade deals, which were highly unlikely to be on as favorable terms as the old EU agreements. Offices of EU research institutions were closed. And these are just examples. The list of losses is substantial.

The post below estimates the total damage to the UK and also compares it to earlier estimates. The outcome is even worse than generally anticipated due to the costs being durable, as opposed to losses that the UK could claw back over time.

By Nicholas Bloom, William Eberle Professor of Economics Stanford University; Philip Bunn, Senior Technical Advisor in the Structural Economics Division Bank Of England; Paul Mizen, Professor in Economics and Vice Dean, Research, at King’s Business School King’s College London; Pawel Smietanka, Research Economist Bank Of England; Senior Economist Deutsche Bundesbank; and Gregory Thwaites, Research Director Resolution Foundation; Associate Professor University Of Nottingham. Originally published at VoxEU

The UK is once again debating why its economy has grown slowly since the mid‑2010s. This column examines the impact of the decision to leave the European Union in 2016. Using almost a decade of data since the referendum, the authors combine simulations based on macro data with estimates derived from micro data. These estimates suggest that by 2025, Brexit had reduced UK GDP by 6% to 8%, with the impact accumulating gradually over time. Investment, employment, and productivity were all affected, reflecting a combination of elevated uncertainty, reduced demand, diverted management time, and increased misallocation of resources.

The UK is once again debating why its economy has grown slowly since the mid‑2010s. Real wages have barely risen, investment has been weak, and productivity growth has disappointed. Many factors are at play – from the global financial crisis hangover to the Covid‑19 pandemic and the energy price shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – but one candidate has been central to the policy debate for nearly a decade: Brexit.

A large literature anticipated substantial long‑run costs of leaving the EU Single Market and Customs Union (HM Treasury 2016, IMF 2016, Van Reenen et al 2016). Early ex‑post work using macro data also pointed to a sizeable hit to UK GDP and trade (Born et al. 2019, Dhingra and Sampson 2022, Springford 2022, Haskel and Martin 2023, Freeman et al. 2025). VoxEU has been an important forum for this research and debate. Our contribution is to revisit the question now that almost a decade has passed since the referendum, bringing together macro and micro evidence in a single framework and comparing actual outcomes to the profession’s pre‑referendum forecasts.

In a new paper (Bloom et al. 2025), we combine micro data collected through the Decision Maker Panel (DMP), a survey of UK firms, with publicly available macro data to estimate the impact of Brexit. Our three main findings are:

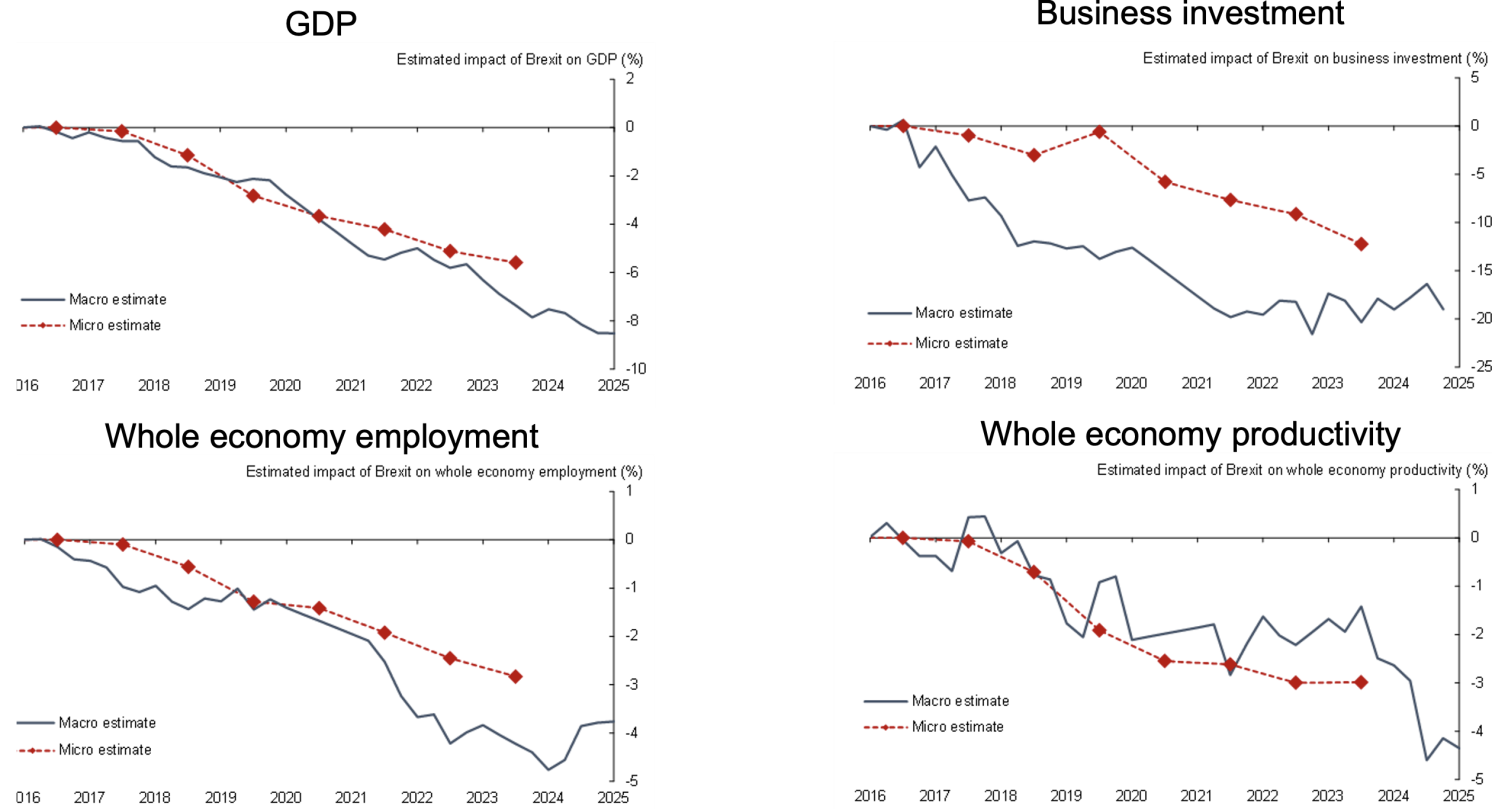

- Brexit has had a large and persistent effect on the UK economy. By 2025, we estimate that UK GDP per capita was 6–8% lower than it would have been without Brexit. Investment was 12–18% lower, employment 3–4% lower, and productivity 3–4% lower.

- These losses emerged gradually. The impact was hard to see in 2017–18, but accumulated steadily over the subsequent decade as uncertainty persisted, trade barriers rose, and firms diverted resources away from productive activity.

- Economists were roughly right on the magnitude of the impact, but wrong on the timing. The consensus pre‑referendum forecast of a 4% long‑run GDP loss turned out to be close to the actual loss after five years, but too optimistic about the longer run.

Measuring Brexit’s impact: Macro Evidence

Our first approach compares the UK’s post‑2016 performance with that of similar advanced economies. The idea, which has been widely used on VoxEU to assess the consequences of Brexit and other policy shocks (e.g. Born et al. 2019), is to construct an estimate of what the UK economy might have looked like in the absence of Brexit, based on the experience of other countries and then ask how actual UK outcomes diverged from this counterfactual.

We use quarterly data for 33 advanced economies (the EU27, the US, Canada, Japan, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland) from 2006 to 2025, and examine GDP per capita, business investment, employment and labour productivity. Because there is no uniquely ‘correct’ way to weight the comparator countries, we consider five different approaches: a simple unweighted average, a GDP‑weighted average, a gravity‑weighted average (GDP divided by distance), a trade‑weighted average, and a formal synthetic control. Our headline estimates take the simple average across these five methods, which draw similar conclusions irrespective of the weighting scheme, including when no weighting is used.

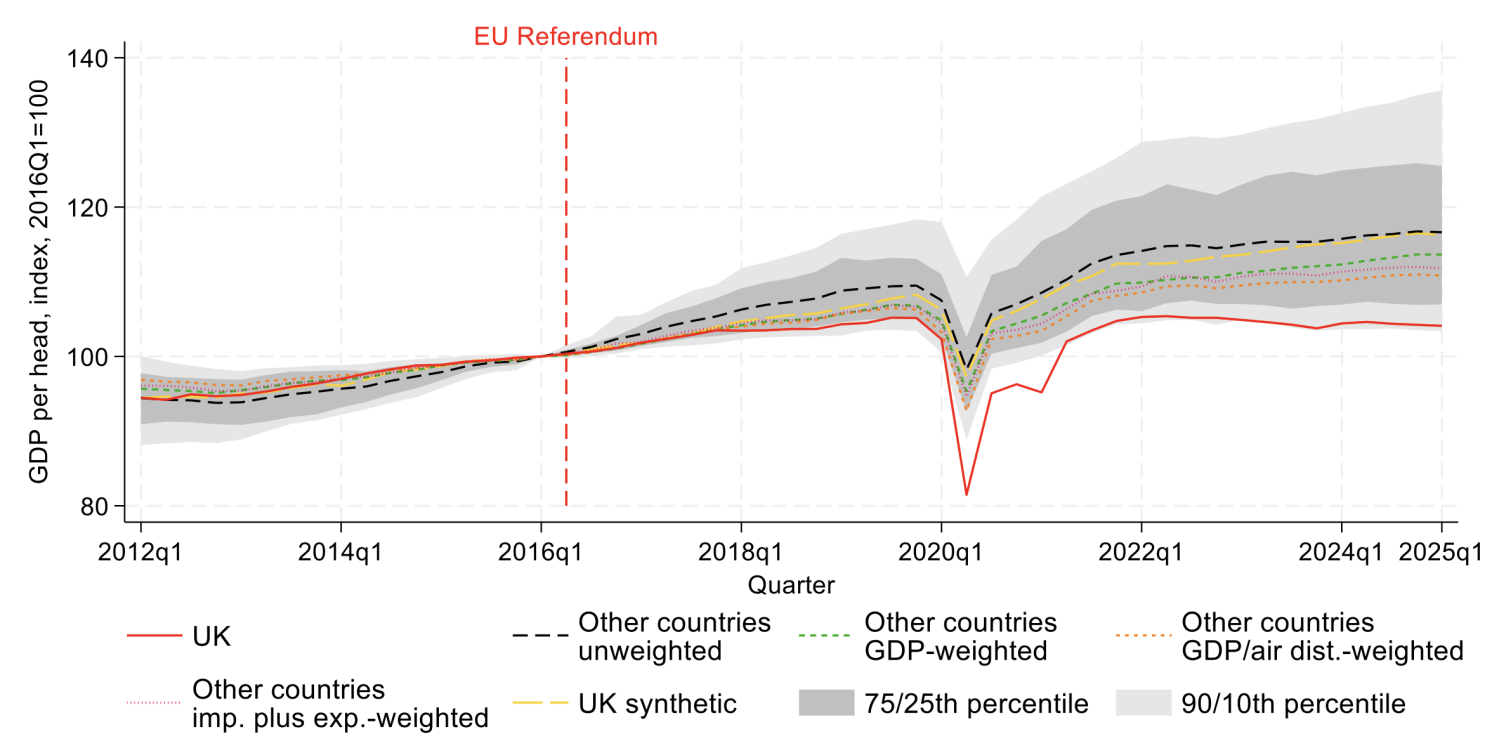

Figure 1 shows that before the referendum, UK GDP per capita grew at broadly the same pace as in the comparison group. After 2016, the lines diverge. By the year to 2025 Q1, UK GDP per head had grown 6–10 percentage points less than in comparable economies, and only about 4% in absolute terms over the whole period. Our central estimate – the average across the five weighting schemes – is that UK GDP per head has grown by a total of around 8% less than that of comparable advanced economies since 2016.

We see similar patterns for other aggregates:

- Business investment was particularly hard hit. The UK went from being a relatively strong performer pre‑referendum to a laggard afterwards. By 2025, business investment was 12-18% below the level implied by the comparator economies.

- Employment has also underperformed, but to a lesser extent: we estimate a shortfall of around 4% relative to the counterfactual.

- Labour productivity was around 4% below the comparator group by 2025.

Figure 1 GDP per capita cross-country comparison

These macro comparisons are not without caveats. The underlying assumption is that the UK would have performed as well as some average of other countries in the absence of Brexit. But this might not be true. The Covid‑19 pandemic and the energy shock affected countries differently; policy responses, including the UK’s furlough scheme and subsidy to household energy bills, also varied. Moreover, Brexit almost certainly had some negative spillovers on EU trading partners, which would bias our estimates downwards. For these reasons, we complement the macro analysis with a micro‑econometric approach based on data from firms located in the UK.

These macro comparisons are not without caveats. The underlying assumption is that the UK would have performed as well as some average of other countries in the absence of Brexit. But this might not be true. The Covid‑19 pandemic and the energy shock affected countries differently; policy responses, including the UK’s furlough scheme and subsidy to household energy bills, also varied. Moreover, Brexit almost certainly had some negative spillovers on EU trading partners, which would bias our estimates downwards. For these reasons, we complement the macro analysis with a micro‑econometric approach based on data from firms located in the UK.

Micro Evidence

The outcome of the Brexit vote in 2016 was widely regarded as a surprise. This discrete, largely unanticipated event allows us to adopt a difference‑in‑differences strategy using firm‑level data.

Our micro analysis exploits the fact that Brexit’s impact varied systematically with firms’ pre‑referendum exposure to the EU. Using the Decision Maker Panel – a large monthly survey of UK firms – we construct a broad measure of prior EU exposure that averages six dimensions: export share to the EU, import share from the EU, dependence on EU migrant workers, exposure to EU regulation, share of directors who are EU nationals, and EU ownership. These survey measures are matched to company accounts data.

Firms with higher EU exposure grew faster than others before 2016. After the referendum, this pattern reversed. Conditional on firm and time fixed effects and controlling for Covid‑related shocks, our micro-based results imply the following aggregate impacts:

- Lower investment growth cumulating to a 12% shortfall in the level of business investment by 2023/24.

- Lower employment growth around 0.5 percentage points lower per year, implying a 3–4% lower level of employment by 2023/24.

- Total factor productivity (TFP) growth around 0.5 percentage points lower per year, leading to a 3–4% reduction to within‑firm TFP by 2023/24.

The micro approach has a different set of considerations to the macro approach. The more direct link to EU exposure can help to better identify the causal effects of Brexit. But we have to assume that unexposed firms were not affected by Brexit, when in fact they could have faced negative spillovers (for example, through demand or supply chains) or positive spillovers (for example, through the labour market if unexposed firms found it easier to hire workers). Broadly speaking, the macro- and micro‑based estimates of the impact on GDP, investment, employment and productivity line up reasonably well, with the macro estimates typically being the larger of the two (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The estimated impact of Brexit

Why Did the Damage Take So Long To Show Up?

Our analysis suggests four main channels through which Brexit affected the UK economy, all of which operated gradually:

- Persistent uncertainty. Brexit generated an unusually long‑lasting period of policy uncertainty. Our Brexit Uncertainty Index, based on the DMP, measures the share of firms reporting Brexit as one of their top three sources of uncertainty. This index rose sharply after the referendum and remained elevated until well after the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) took effect in 2021. Investment is particularly sensitive to uncertainty, and our firm‑level regressions suggest that the uncertainty channel explains much of the post‑2016 weakness of investment.

- Higher trade costs and lower demand. Even though the TCA preserves zero tariffs and quotas on most UK‑EU trade, leaving the Single Market and Customs Union has introduced substantial non‑tariff barriers. Other work has documented sharp falls in UK–EU goods trade around 2021 and persistent disruptions to supply chains and services trade (Dhingra and Sampson 2022, Freeman et al. 2025). Lower expected demand, especially in tradable sectors, appears to have been to be a key driver of weaker employment growth.

- Less innovation and management time being diverted. Productivity within firms may have been affected by firms cutting back on productivity-enhancing forms of investment, and by management time being diverted from other activities to prepare for Brexit.

- Reallocation away from highly productive, internationally exposed firms. The firms most exposed to the EU tend also to be the most productive, and these were the firms that were most negatively impacted by Brexit.

Taken together, these channels help explain why the economic impact of Brexit has been a slow‑burn phenomenon. Rather than a single cliff‑edge event, the UK experienced a drawn‑out process of negotiation, transition, and implementation, with uncertainty and adjustment costs stretching over almost a decade.

How Did the Pre‑Referendum Forecasts Perform?

The Brexit referendum offers a rare opportunity in macroeconomics to compare ex‑ante forecasts with ex‑post outcomes. IMF (2016) summarised the predictions of academic and professional economists about the long‑run impact of Brexit on UK GDP. The average forecast in that survey was a 4% loss of GDP relative to remaining in the EU, with most of the impact assumed to materialise within five years.

Our estimates suggest that this consensus forecast performed reasonably well over a five‑year horizon: we find a GDP shortfall of 4–6% by 2021. But by 2025 the loss had deepened to 6–8%. In other words, economists were broadly right on the direction and order of magnitude of the long‑run impact, but they underestimated how drawn‑out the Brexit process would be and therefore how persistent the associated uncertainty and adjustment costs would prove.

This has broader implications for how we evaluate macro forecasts around major political events. The Brexit experience suggests that getting the economics ‘right’ is not enough; the political economy of implementation – including the possibility of delays, renegotiations and partial reversals – can materially affect both the timing and the eventual size of the economic impact.

Lessons for Future Trade Fragmentation

The UK’s exit from the EU is a unique event. No other large economy has voluntarily stepped back from such deep integration with its neighbours. But the mechanisms we document are likely to be relevant for other episodes of trade and migration fragmentation, including the imposition of tariffs, sanctions and tighter migration controls elsewhere.

Our work shows that disengaging from global trade and production networks can carry large and long‑lasting economic costs, and these costs tend to accumulate slowly rather than appearing overnight. In the case of Brexit, there was a substantial economic impact on the UK economy.

See original post for references

I was a British Remainer living in France when I used my vote in that cause. I already had signals from the mainland that the Referendum was likely to result in a leave vote, not least because of failures of the political class during the 2008 crisis, the unnecessary and vicious application of austerity measurs on those least capable of bearing them, EU skilled and unskilled migrants from the Eastern Eastern European bloc which entered the EU at the start of 2004 placing downwards pressure on the earnings of British workers and the effect their numbers had on the NHS and the housing market, and the generalised sense that the EU and its institutions were increasingly overriding the interests and the political will of ordinary Britons. The EU already had a reputation for re-litigating decisions which went against its interests as an institution with regard to the electoral legitimacy.

Therefore, seeing the chaos likely to result from any delay in giving immediate notice to the EU, as Jeremy Corbyn suggested to the displeasure of his MPs whilst increasing his attractions as a political leader which paid off in the size of the Labour vote in the 2017 General Election. If it wasn’t for the fully documented electoral corruption of the Labour Party’s proffesional apparatchiks and Starmer’s declaration that there would be a second referendum over the terms of the final agreement with the EU and Remain would be one of the choices on the ballot, JC would likely have become prime minister of a minority government or of a government with a small majority in the House of Commons.

Under the pressure of having to reach a settlement within less than twelve months, the EU would most likely have had to concede more and the UK less than was the case in 2020 when opinions in Brussels had hardened and British politicians and the civil service would have dealt with the substantive issues in play and would have parked the doctrinal issues on one side and we probably would have settled nicely into the EU Customs Union as a classic Britsh compromise that would have settled the issue for most Brits and the overwhelming majority of EU members.

As it was we ended up with a very, very dirty clean break as we entered the Covid period without having engaged in serious negotiations with either the EU or the two most obvious future trading partners, China and Russia, ending our chances of reaching an understanding with the latter by our refusal to understand why overthrowing a legitmate government in a US-SIS plot a year before an election in the Ukraine might have upset Russia, not to mention the inanity of the Skripal-Novichok false flag in Salisbury. The UK was no longer a country whose interests were paramount, it was a mere appendage leaning on the hegenomic dogma of the United States and of little other consequence to the world.

Rather than breaking for a new pathway and developing appropriate economic and diplomatic policies to protect our vital interests we ended up trundling along the same old pathway taking us over the cliff edge without the glamour or the sense of having consciously made an existential decision unlike, for instance, Thelma and Louise.

The authors of this paper seem to indicate that an alternative approach to Brexit was possible but they obviously fail to understand that effective policy implementation demands that you have a policy in the first place which offers specific actionable alternatives: “The Brexit experience suggests that getting the economics ‘right’ is not enough; the political economy of implementation – including the possibility of delays, renegotiations and partial reversals – can materially affect both the timing and the eventual size of the economic impact.”

Oh, and apart from being party to a war and a genocide alongside the US and the EU which will define this century, our political class chose to be complicit along with the EU and the more idiotic leaders of the member states which fonda Lyin’s apparatchiks have carefully positioned to follow the UK over the cliff.

The decision to rely upon London financial strength was not matched with an industrial policy which should have been in place during the 1970s, before Thatcher took the hatchet to it. The UK should have known that, if you are to go it alone, some self-awareness is necessary. With not much attracting buyers of industrial goods, the UK dealt money and brokerage. A slowdown of economic activity could not be surprising. Of course, the people paying for that slowdown live outside of London, for the most part. They don’t make the papers in the biased British press.

Opinion polls now show a majority of UK electors wish the UK to rejoin the EU, Brexit being seen as a failure. This could become a live political issue again in the run-up to an election in 2029.

As I was reading this, KLG’s post from yesterday came to mind, specifically the long-term costs imposed by decision-makers who fail or choose not to recognize all of the potential ramifications of the decisions they make.

Our system of governance is in dire need of a course-correction.

That Brexit was an act of economic self-harm strikes me as uncontroversial. But I can’t shake the feeling that the authors of this paper (and likely the bulk of their intended readership) are engaged in an ongoing dialogue among the obtuse. They simply refuse to acknowledge that something approximating a majority of the UK electorate was dissatisfied with the prevailing arrangements and were NOT interested in seeing them continue — whether the economic outcome of Brexit would be slightly better or worse wasn’t going to affect their determination to cram a stick into the spokes of a political economic machine which has for decades ignored them and they felt was clearly inimical to their wellbeing, and worse, one run by a habitually smug coterie of finance and political “elites” who sneered at their folkways at every opportunity whilst finding common cause with the “citizens of nowhere” among the Davos set.

No amount of quibbling over whether or not the economic outcomes match their forecasts changes the fundamental fact that these people are politically and culturally clueless. Someone really ought to slap some sense into them.

“Something approximating a majority of UK electorate …” It was 52% to 48% with a turnout of 72% so c.37% of the electorate voted to leave.

Many are finding ways to bypass Brexit:

250,000 applications for Irish passports in 2024.