Yves here. It is depressing but climate engineering, aka geo-engineering, is inevitable. Our putative betters are not just not doing remotely enough to try to slow the pace of global warming but are going pedal to the metal in making matters worse with their AI fevered dreams and related energy-hogging data center buildouts. Even with them using electricity, the demands are so high that it seems heroically optimistic to posit that all can or will come from solar or nuclear.

By Kelsey Roberts, Post-Doctoral Scholar in Marine Ecology, Cornell University; UMass Dartmouth; Daniele Visioni, Assistant Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University; Morgan Raven, Associate Professor of Marine Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara; and Tyler Rohr, ARC DECRA Fellow/Senior Lecturer, IMAS, University of Tasmania. Originally published at The Conversation

Climate change is already fueling dangerous heat waves, raising sea levels and transforming the oceans. Even if countries meet their pledges to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change, global warming will exceed what many ecosystems can safely handle.

That reality has motivated scientists, governments and a growing number of startups to explore ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or at least temporarily counter its effects.

But these climate interventions come with risks – especially for the ocean, the world’s largest carbon sink, where carbon is absorbed and stored, and the foundation of global food security.

Our team of researchers has spent decades studying the oceans and climate. In a new study, we analyzed how different types of climate interventions could affect marine ecosystems, for good or bad, and where more research is needed to understand the risks before anyone tries them on a large scale. We found that some strategies carry fewer risks than others, though none is free of consequences.

What Climate Interventions Look Like

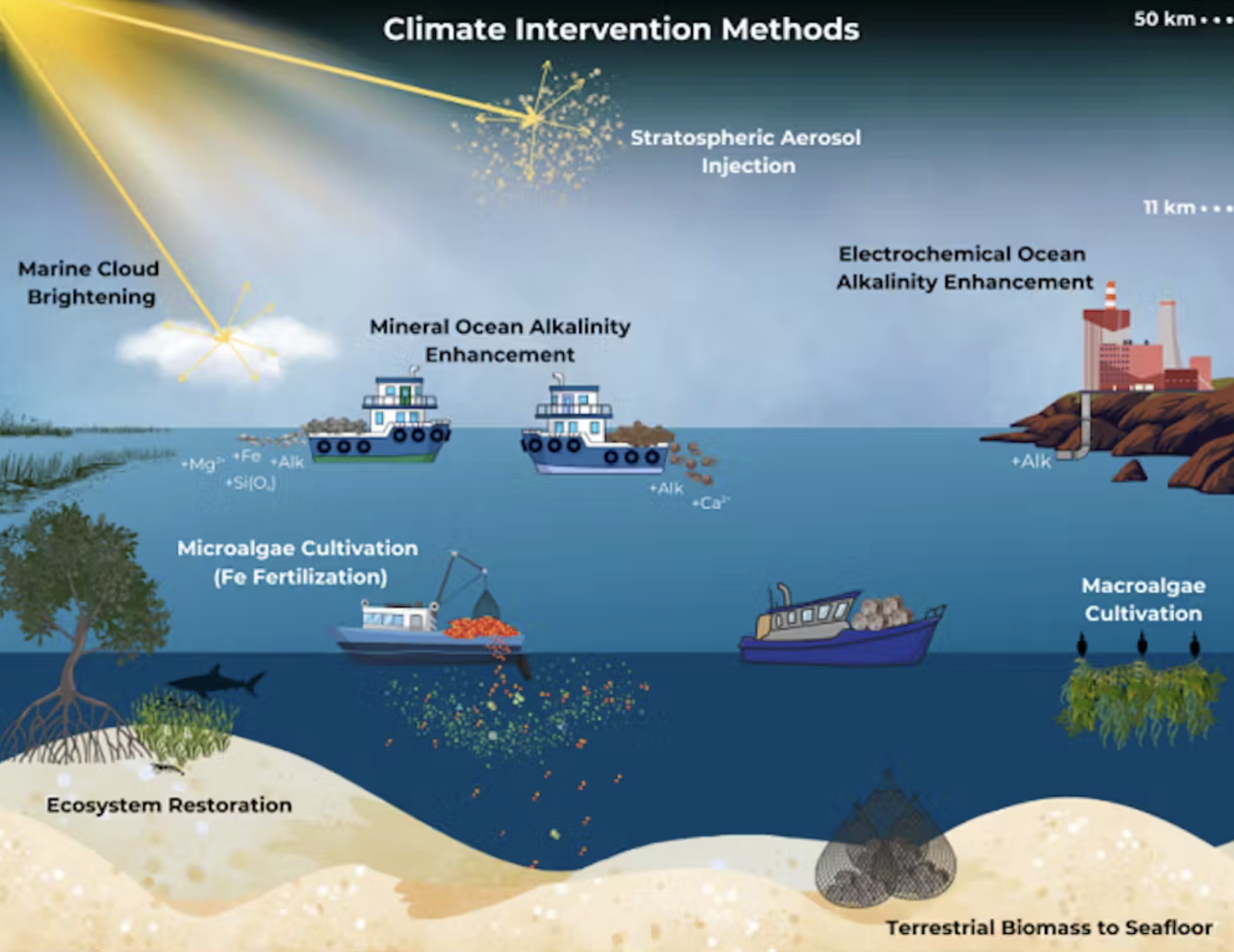

Climate interventions fall into two broad categories that work very differently.

One is carbon dioxide removal, or CDR. It tackles the root cause of climate change by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

The ocean already absorbs nearly one-third of human-caused carbon emissions annually and has an enormous capacity to hold more carbon. Marine carbon dioxide removal techniques aim to increase that natural uptake by altering the ocean’s biology or chemistry.

Biological carbon removal methods capture carbon through photosynthesis in plants or algae. Some methods, such as iron fertilization and seaweed cultivation, boost the growth of marine algae by giving them more nutrients. A fraction of the carbon they capture during growth can be stored in the ocean for hundreds of years, but much of it leaks back to the atmosphere once biomass decomposes.

Other methods involve growing plants on land and sinking them in deep, low-oxygen waters where decomposition is slower, delaying the release of the carbon they contain. This is known as anoxic storage of terrestrial biomass.

Another type of carbon dioxide removal doesn’t need biology to capture carbon. Ocean alkalinity enhancementchemically converts carbon dioxide in seawater into other forms of carbon, allowing the ocean to absorb more from the atmosphere. This works by adding large amounts of alkaline material, such as pulverized carbonate or silicate rocks like limestone or basalt, or electrochemically manufactured compounds like sodium hydroxide.

Solar radiation modification is another category entirely. It works like a sunshade – it doesn’t remove carbon dioxide, but it can reduce dangerous effects such as heat waves and coral bleaching by injecting tiny particles into the atmosphere that brighten clouds or directly reflect sunlight back to space, replicating the cooling seen after major volcanic eruptions. The appeal of solar radiation modification is speed: It could cool the planet within years, but it would only temporarily mask the effects of still-rising carbon dioxide concentrations.

These Methods Can Also Affect Ocean Life

We reviewed eight intervention types and assessed how each could affect marine ecosystems. We found that all of them had distinct potential benefits and risks.

One risk of pulling more carbon dioxide into the ocean is ocean acidification. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms acid. This process is already weakening the shells of oysters and harming corals and plankton that are crucial to the ocean food chain.

Adding alkaline materials, such as pulverized carbonate or silicate rocks, could counteract the acidity of the additional carbon dioxide by converting it into less harmful forms of carbon.

Biological methods, by contrast, capture carbon in living biomass, such as plants and algae, but release it again as carbon dioxide when the biomass breaks down – meaning their effect on acidification depends on where the biomass grows and where it later decomposes.

Another concern with biological methods involves nutrients. All plants and algae need nutrients to grow, but the ocean is highly interconnected. Fertilizing the surface in one area may boost plant and algae productivity, but at the same time suffocate the waters beneath it or disrupt fisheries thousands of miles away by depleting nutrients that ocean currents would otherwise transport to productive fishing areas.

Ocean alkalinity enhancement doesn’t require adding nutrients, but some mineral forms of alkalinity, like basalts, introduce nutrients such as iron and silicate that can impact growth.

Solar radiation modification adds no nutrients but could shift circulation patterns that move nutrients around.

Shifts in acidification and nutrients will benefit some phytoplankton and disadvantage others. The resulting changes in the mix of phytoplankton matter: If different predators prefer different phytoplankton, the follow-on effects could travel all the way up the food chain, eventually impacting the fisheries millions of people rely on.

The Least Risky Options for the Ocean

Of all the methods we reviewed, we found that electrochemical ocean alkalinity enhancement had the lowest direct risk to the ocean, but it isn’t risk-free. Electrochemical methods use an electric current to separate salt water into an alkaline stream and an acidic stream. This generates a chemically simple form of alkalinity with limited effects on biology, but it also requires neutralizing or disposing of the acid safely.

Other relatively low-risk options include adding carbonate minerals to seawater, which would increase alkalinity with relatively few contaminants, and sinking land plants in deep, low-oxygen environments for long-term carbon storage.

Still, these approaches carry uncertainties and need further study.

Scientists typically use computer models to explore methods like these before testing them on a wide scale in the ocean, but the models are only as reliable as the data that grounds them. And many biological processes are still not well enough understood to be included in models.

For example, models don’t capture the effects of some trace metal contaminants in certain alkaline materials or how ecosystems may reorganize around new seaweed farm habitats. To accurately include effects like these in models, scientists first must study them in laboratories and sometimes small-scale field experiments.

A Cautious, Evidence-Based Path Forward

Some scientists have argued that the risks of climate intervention are too great to even consider and all related research should stop because it is a dangerous distraction from the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

We disagree.

Commercialization is already underway. Marine carbon dioxide removal startups backed by investors are already selling carbon credits to companies such as Stripe and British Airways. Meanwhile, global emissions continue to rise, and many countries, including the U.S., are backing away from their emissions reduction pledges.

As the harms caused by climate change worsen, pressure may build for governments to deploy climate interventions quickly and without a clear understanding of risks. Scientists have an opportunity to study these ideas carefully now, before the planet reaches climate instabilities that could push society to embrace untested interventions. That window won’t stay open forever.

Given the stakes, we believe the world needs transparent research that can rule out harmful options, verify promising ones and stop if the impacts prove unacceptable. It is possible that no climate intervention will ever be safe enough to implement on a large scale. But we believe that decision should be guided by evidence – not market pressure, fear or ideology.

The bursting of the AI bubble will likely be followed by the rise of a geoengineering bubble.

Nah. That would require the billionaires to give a shit. The AI bubble only works because they are promising a techno sci-fi future. Geoengineering merely maintains the boring status quo.

As Yves says, climate engineering is inevitable. Some country will try it, and if they feel it’s a national emergency, they won’t ask permission from the rest of us. China is already actively trying regional based methods in the Himalaya, and these have very clear potential transnational risks.

It is mentioned in passing above, but I do think that the use of rocks like olivine has a lot of potential for ocean de-acidification and CO2 absorption. It would be nice to have a generations worth of research on this, but we are already out of time for that.

Yes, almost certainly, but with money incentives it is nearly guaranteed that not everyone will follow with the recommendation of transparent research and ruling out harmful options. Even worse, given how we are being ruled with a “geostrategic” (confrontational) mindset one can foresee that geoengineering might turn to be just another tool of “hybrid warfare”.

Some of the ideas being proposed there in the graph show, in my opinion, how deluded we are. Take that of Fe fertilization for micro-algae growth boosting. Much of ocean fertilization depends on ocean currents and if these slow down as a consequence of global warming y bet we won’t be able to offset the trend in any way or form. I would really like to hope that ideas such as ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE), some call it “anthropogenic alkalinity” might somehow work at scale and without risks. We, for instance, have to account for negative interactions between OAE and natural alkalinization and determine whether the methods proposed have any additive effect after all. If that is solved, start thinking how feasible is the geographical deployment of OAE.

Let’s recall a simple fact. Of all the extra CO2 we produce, about half goes to the ocean, and makes it more acidic while killing the coral reefs, and about half stays in the atmosphere to do some melting and warming. Even if one succeeds in removing extra CO2 from one reservoir, thermodynamics will have it resupplied from the other, so one should consider the Earth’s system as a single reservoir.

Many solutions require quite some energy. Eg injecting stuff in the stratosphere on a daily or weekly basis has a huge cost. And we get to the usual issue: why should country X pay or do something that profits to all?

Other solutions are only local or temporary. Eg algae cultivation may concentrate CO2 from the neigborhood into the algae, but that CO2 is still going around and will get back into the Earth reservoir a bit later.

One may grow forests, but that only delays the CO2 getting back into the reservoir.

Other solutions like alcanity enhancement only consider a subset of the problem. E.g. the article above states “Electrochemical methods use an electric current to separate salt water into an alkaline stream and an acidic stream”. One sees already the energy requirements (and the “who pays the bills?” question) to create the alkaline stream, but we also end up with an acidic stream, which in the end can only be removed by using up the alcalinity we set out to create. So at the end of the day, we’ve just spent a lot of money and energy. And probably generate some waste also.

/sarc on

So I would like to put forward a modest proposal.

The only solution that is cheap, universally applicable and efficient, is the one used since forever in geochemical processes: carbon is stored in organic life-forms, the life-forms die and fall to the bottom of the ocean, and the carbon of the skeletons is definitely removed from the cycle. It might pop up again several millions of years later as talc, marble or other stuff, but always harmless.

So my proposal is to incite people to board wooden boats to cross an ocean going from a water-poor region to a water-rich environment. Submarines can then sink those boats anywhere over the oceans. Once sunk, the carbon of the boats and the people gets removed forever from the carbon cycle.

There are additional advantages: the wood required to build the boats, is an incentive to grow more forests, always a plus, and the sinking of the boats makes there will be less humans to share the limited resources.

I leave it as an exercise to the reader to identify the interesting grift opportunities.

/sarc off

De-salination plants pushing the salts back into the oceans near the coasts won’t help either.

> And we get to the usual issue: why should country X pay or do something that profits to all?

: Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it. Those who remember history but are outnumbered by those who forget are also doomed to repeat it.

Being outnumbered is a problem. Nowak: if n is the maximum group size and m the number of groups, then group selection allows evolution of cooperation provided 𝑏/𝑐>1+𝑛/𝑚. [Where b/c = benefit/cost.]

Another way to say it is, if everyone suffers, there’s not enough variance to drive change. Turchin’s version of Price’s Equation captures this (see the Chapter 4 entry).

There is route toward cooperation/altruism, however. Greenhouse gas production is not evenly distributed among the population. If there was a small group of extreme polluters, then the math works for moralistic punishers to act.

[Note the equations carry simplifying assumptions. Add the assumption that the heat and byproducts generated by climate engineering will, in a complex system, actually dampen significant climate change, when positive feedback loops are kicking in. See:

Gridded maps of wetlands dynamics over mid-low latitudes for 1980–2020 based on TOPMODEL

[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361392409_Gridded_maps_of_wetlands_dynamics_over_mid-low_latitudes_for_1980-2020_based_on_TOPMODEL]

Warfare and the Evolution of Social Complexity: A Multilevel-Selection Approach [https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7j11945r]

Thank you all. This,

already selling carbon credits to companies such as Stripe and British Airways.

If profits and profiteers are to be the polestar and guides on this journey, never mind. There’s no quick fix and time is not on our side. Maybe China, which appears to be a serious country, still believes in science, and has a better understanding of scale, can sort this. My opinion is this is beyond the reach of man now. We are too far into the curve.

So, just doing less with less is not a serious proposition? /s

Do you see anyone taking that up? We’ve been advocating that for years. The Green New Deal, as we have remarked way too many times, is a way to pretend that techno-hopium will allow for modern lifestyles to continue with only nice changes at the margin, like biking and eating more veggies and less meat.

The rich who are the big sinners are doing nada.

According to paleontologist Peter Ward (Under a Green Sky, 2007) atmospheric carbon released by the eruption of the Siberian Traps caused acidification of the ocean which in turn caused a massive die-off of the plankton which produces most of the world’s oxygen. This, he argues, was responsible for the Permian mass extinction, the worst in the planet’s history. Would geoengineering give us a false sense of confidence until it is too late?

I’m a big fan of Peter Ward’s books. His later book, The Medea Hypothesis, deliberately counterpoints the Gaia hypothesis and shows how life tends to do things that put its survival at risk. This interview gives the general flavour of the book.

Thanks for the reference. The Gaia Hypothesis was, as he says, New Age mysticism but we should be careful of going too far the other way. There is a lot of cooperation in nature as well.

Why do I feel like I’m on the ‘Titanic’?!

Maybe watching our fearless leaders rearranging the deck chairs?

The biggest risk of geo-engineering is that it will create a permission structure for ongoing burning of fossil carbon. The ongoing carbon skydumping will acidize the oceans so much that most edible life in the oceans will be destroyed. If all the phytoplankton is acidized to death, where does the atmospheric oxygen maintainance come from?

Climatologist Katharine Hayhoe has popularized the term “Global Weirding.” Global Warming sounds like it might be a simple problem with a simple solution. However, Hayhoe holds that it is not that simple. Weird things happen! The polar vortex destabilizes and suddenly the United States is experiencing record cold winter temperatures from Minnesota to Florida. Everything gets weird. Into all this weirdness steps geo-engineering. The acidification of the oceans does not just weaken oyster shells, with a little more boost it could kill everything in the ocean that has bones or shells. To ignore the fundamental cause, global warming, and to hope that we can manage weird side-effects is to gamble with both the ecosystem of the ocean and with a major human food source. If every nation is left to “fix” its own corner of the environment for its own purposes, then, as suggested above, we can count on geo-engineering to morph in geo-warfare. Treating the symptoms while ignoring the cause is just giving one more cigarette to a man dying of lung cancer. Global warming is like an earthquake, we hope “the big one” will not come this year, even as we realize every year we wait, the eventual quake just gets larger. I know. I live in Oregon! I guess I am gambling that global warming is going to blow before the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Weird!

Isn’t the fundamental cause of all this the ongoing runaway carbon skydumping? Isn’t global warming just one outcome, and global weirding another outcome and ocean acidation yet another outcome of the basic cause which is runaway carbon skydumping?

Parasites attacking each other

Amazon threatens ‘drastic’ action after Saks bankruptcy, says $475M stake is now worthless

Climate engineering, in my humble opinion, is the ultimate act of an out-of-control species [us humans] to manipulate the planet’s natural environment in order to compensate for our extremely destructive behaviour – and utter failure to live sustainably on it. It is also an admission that we effectively refuse to change our destructive habits. Hubris of the worst order!

It will certainly fail, perhaps not in the short term, but in the mid to long term – as the consequences of our interventions become apparent along with the reluctant realisation of how little we really understand the mechanisms of the planet to regulate and keep itself in balance.

We will only push it over the tipping point – quicker than if we do nothing.

The other huge risk, is that some Western countries, like the USA, will try to weaponise the techniques against other countries [when does the US NOT weaponise new technologies?].

Let’s not delude ourselves, we WILL screw it up – badly. We will mismanage every aspect of it – the science, the implementation, the politics, the international impact, etc.

When it comes to the environment when do we ever get it right?

Another solution for carbon capture is farmland. Now, the dominant agriculture depends on fossil fuels for fertilizer and pesticides, which are known over time to reduce soil health as they replace natural bio-organisms with a fix of nitrate, thus degrading the soil’s ability to hold carbon. Returning to an organic, sustainable farming and gardening method would revitalize soil organisms and restore their ability to hold carbon, while producing superior food.

This kind of renewal would take time and considerable investment in work and capital, so it would be a ‘jobs-creator’ as well as a surplus capital sink. And, the soil could hold a prodigious amount of carbon.

As a side benefit, just returning to ancient, effective farming methods would require such a great attitude shift, that the very use of fossil fuels and their carbon emission would lessen.