Yves here. This post documents how voting systems interact with immigration, or perhaps more accurately, anti-immigration policies. It point out that majority voting systems raise the bar for implementing rules and laws that restrict migration. This is consistent with the experience of the US, with its close to hard-coded two party system and until Trump, liberalized immigration.

By Matteo Gamalerio, Assistant Professor of Economics University Of Barcelona, Massimo Morelli, Professor of Economics and Political Science Bocconi University, and Margherita Negri, Senior Lecturer University of St Andrews. Originally published at VoxEU

Immigration has become one of the most salient issues in political debate. This column uses evidence from Italian municipal elections to highlight the role of electoral rules in shaping immigration policy. Electoral systems where power can be won with a simple plurality of the votes facilitate the rise of anti-immigrant candidates and lead to more restrictive immigration policies. By contrast, systems requiring an absolute majority of the votes force anti-immigrant parties into broader coalitions, resulting in more open immigration outcomes.

Why do some democracies adopt more restrictive immigration policies than others? Voter preferences matter, but so do the salience of political issues (Gidron and Kikuchi 2023) and the rules that convert votes into power. In a recent study (Gamalerio et al. 2025) we show that when immigration becomes highly salient – as in recent years – electoral systems play a crucial role in determining whether anti-immigrant candidates enter the race and, ultimately, the policies that governments implement.

The Weakening of the Left–Right Divide and the Rise of Immigration Politics

For much of the post-war period, political competition in advanced democracies revolved around a single economic divide: the left supported redistribution and an expansive welfare state, while the right favoured limited government and market-oriented policies. Under these conditions, median-voter logic largely explained policy outcomes. Over time, however, confidence in both models eroded. Fiscal crises, corruption, and weak public management undermined faith in state intervention, while globalisation, automation, and financial crises weakened trust in free markets (Colantone and Stanig 2017, Autor et al. 2020, Guiso et al. 2025).

As the traditional left–right divide lost salience, new issues gained prominence (Tabellini 2019, Noury and Roland 2020, Gethin et al. 2022). Immigration, in particular, has become highly salient across Western democracies (Hatton 2021, Dennison and Geddes 2019, Schneider-Strawczynski and Valette, 2025). Immigration blends economic concerns about jobs, welfare, and security with identity-based anxieties about culture and national cohesion (Mayda 2006, Dustmann and Preston 2007, Tabellini 2019), making it a powerful mobilising tool for populist parties.

Figure 1 shows how immigration inflows varied widely across OECD countries from 2000 to 2018, reflecting substantial differences in policy openness. Our study argues that these differences are not driven by preferences alone: the interaction between rising immigration salience and electoral system design plays a central role.

Figure 1 Immigration in OECD countries

Note: OECD data on immigration inflow per 1,000 inhabitants (2000-2018).

Sufficient Plurality vs Necessary Majority

We focus on a key feature of electoral systems: the share of votes necessary to gain control of decision-making power. We distinguish between simple plurality systems, where power can be achieved with a plurality of votes, and necessary majority systems, where a party or coalition must secure at least 50% of the electorate. Necessary majority systems include both proportional representation systems and dual-ballot systems, in which attaining an absolute majority is required to govern.

Our theoretical analysis delivers three predictions. First, necessary majority systems make it less attractive for anti-immigrant parties to run independently. Second, these systems produce more open immigration policies than sufficient plurality ones. Third, the difference between the two rules is largest where opposition to immigration is neither very low nor very high.

The intuition is straightforward. When anti-immigration sentiment is strong but below 50% of the electorate, a standalone anti-immigrant candidate can win under a sufficient plurality system but not under a necessary majority one. If support is overwhelming, anti-immigrant candidates will be likely to win under either system; if it is very low, candidates have no incentives to campaign on anti-immigration platform, regardless of the electoral system.

We tested these predictions using data on Italian municipalities in the period 1993-2012.

Italian Municipal Elections

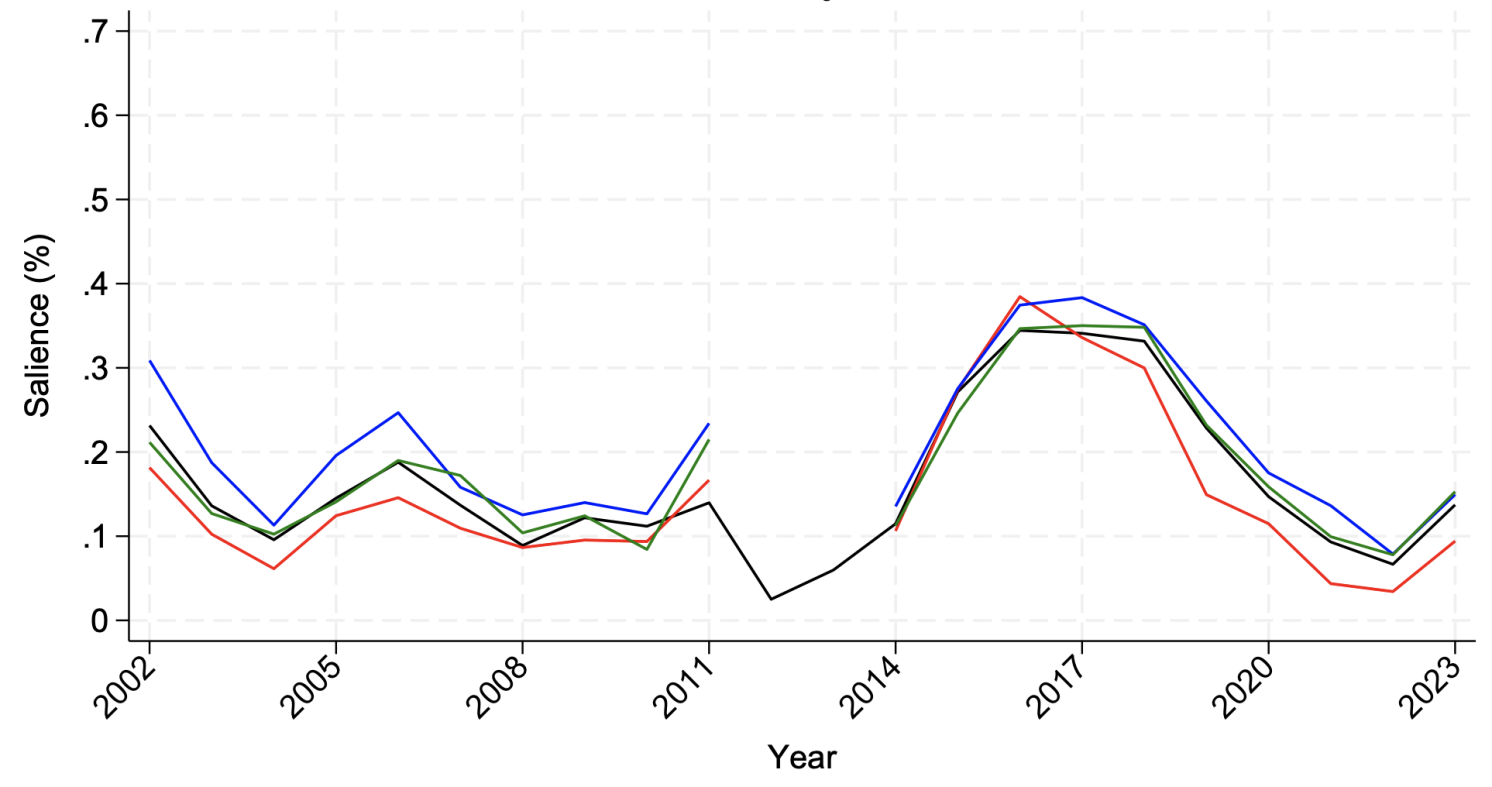

In Italy, public concern about immigration rose sharply over the 2000s: in 2002, only around 20% of Italians listed immigration among their top issues, but by 2016 it had become one of the dominant issues across the political spectrum (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Salience of migration in Italy

Notes: Eurobarometer data on migration salience for Italy (2002-2023). Blue: right-wing voters, red: left-wing voters, green: centrist voters, black: average, including those who did not declare their ideology. Self-reported ideology was not asked in 2012-2013.

Since 1993, Italian mayors have been directly elected. The electoral system changes sharply from plurality rule (a sufficient plurality system) to a dual-ballot system (a necessary majority system) once the municipal population exceeds 15,000 inhabitants (Bordignon et al. 2016). We exploit this institutional threshold to identify the causal effects of different electoral systems through a regression discontinuity design.

Electoral Rules, Anti-Immigrant Candidates, and Local Policy

Italian mayoral candidates are supported by one or more lists for the municipal council. These lists represent national parties, coalitions, or local political organisations (liste civiche). Using information on the party associated with each list, we examine how electoral rules affect the likelihood that standalone anti-immigrant candidates enter the race.

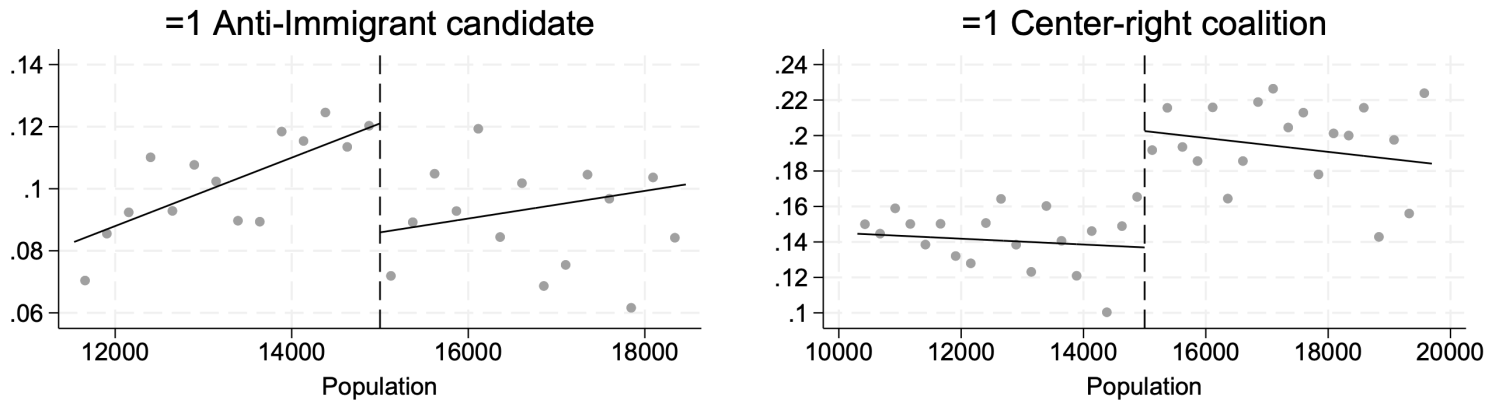

Figure 3 illustrates the results. When the electoral system used to elect the mayor switches from plurality to dual ballot, the probability of observing a candidate backed exclusively by anti-immigrant parties drops sharply – by about 3.5 percentage points (left panel). At the same time, the probability that anti-immigrant parties form a coalition with moderate centre-right parties increases by roughly 6.6 percentage points (right panel). Necessary majority systems, in other words, push anti-immigrant parties into broader (and more moderate) coalitions rather than prompting them to run independently.

Figure 3 Effect of dual ballot on entry of mayoral candidates

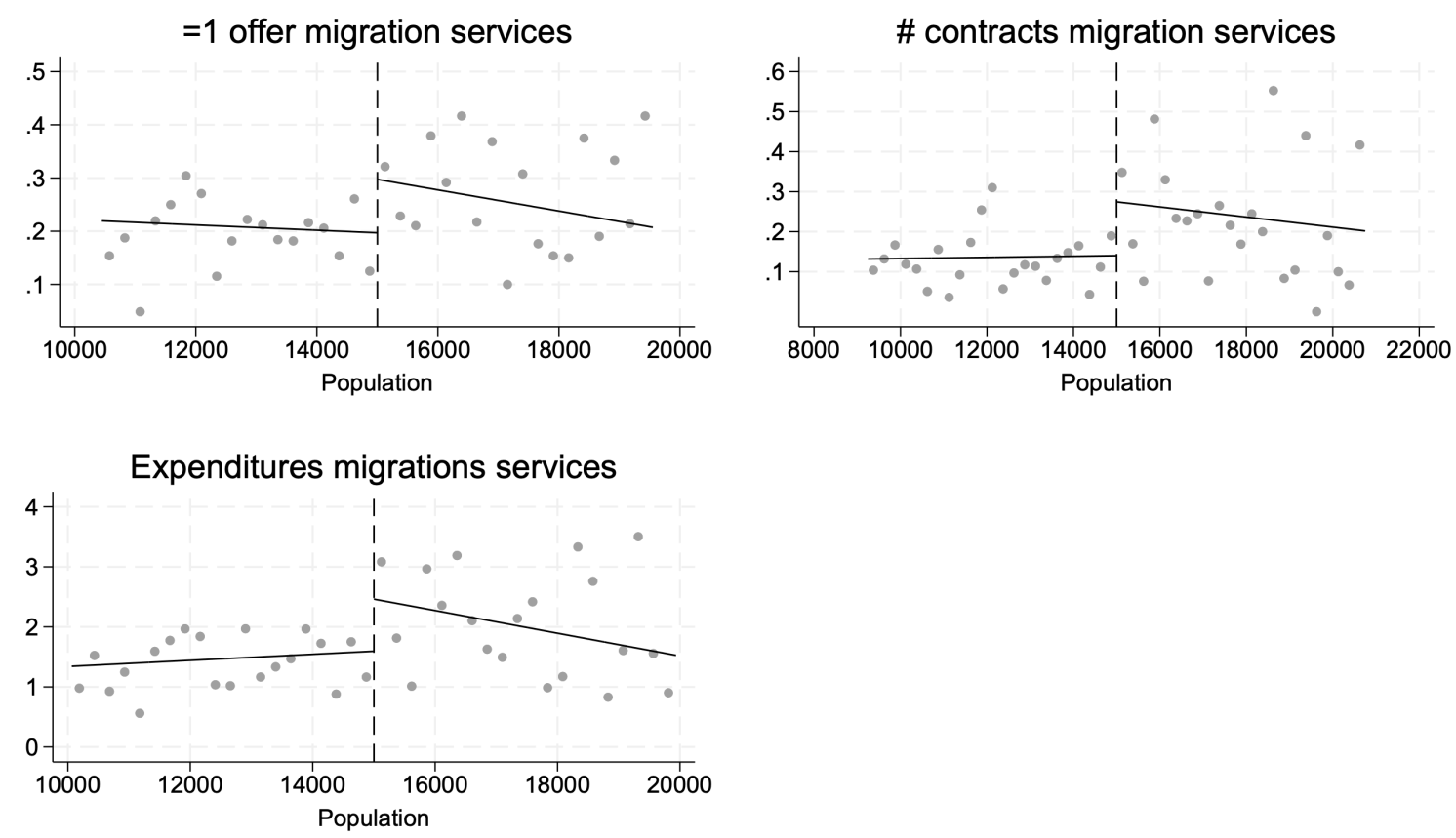

We then turn to policy outcomes. Using data on procurement contracts (Pulejo 2025), we construct three measures of pro-immigration policies: whether a municipality provides any migration-related good or service; the average number of procurement contracts for migration-related goods and services awarded by a municipal government during an electoral term; and the average municipal expenditure over an electoral term devoted to welfare goods and services targeted at the non-native population.

Figure 4 shows that all three measures rise sharply as the electoral system shifts from plurality to dual ballot. Municipalities using dual ballot are about 10 percentage points more likely to provide migration-related services (baseline: 19.8%); they award on average 0.134 additional contracts per electoral term, which corresponds to roughly a 104% increase relative to the baseline mean of 0.129 contracts; and they show an increase of approximately 138% in migrant-related expenditures.

Figure 4 Effect of dual ballot on immigration policies

Finally, we examine how these effects vary with anti-immigration sentiment. Using the vote share of anti-immigrant and far-right parties in 1994-2009 European elections as a proxy for opposition to immigration within a municipality, we divide our sample into tertiles (excluding municipalities above 0.50 due to lack of data) and examine how the effect of the electoral system varies across the three groups. Consistent with our theoretical predictions, we only find an effect for the third tertile, where opposition to migration ranges from 0.198 to 0.494.

Beyond Italian Municipalities: Parliamentary Elections and Cross-Country Evidence

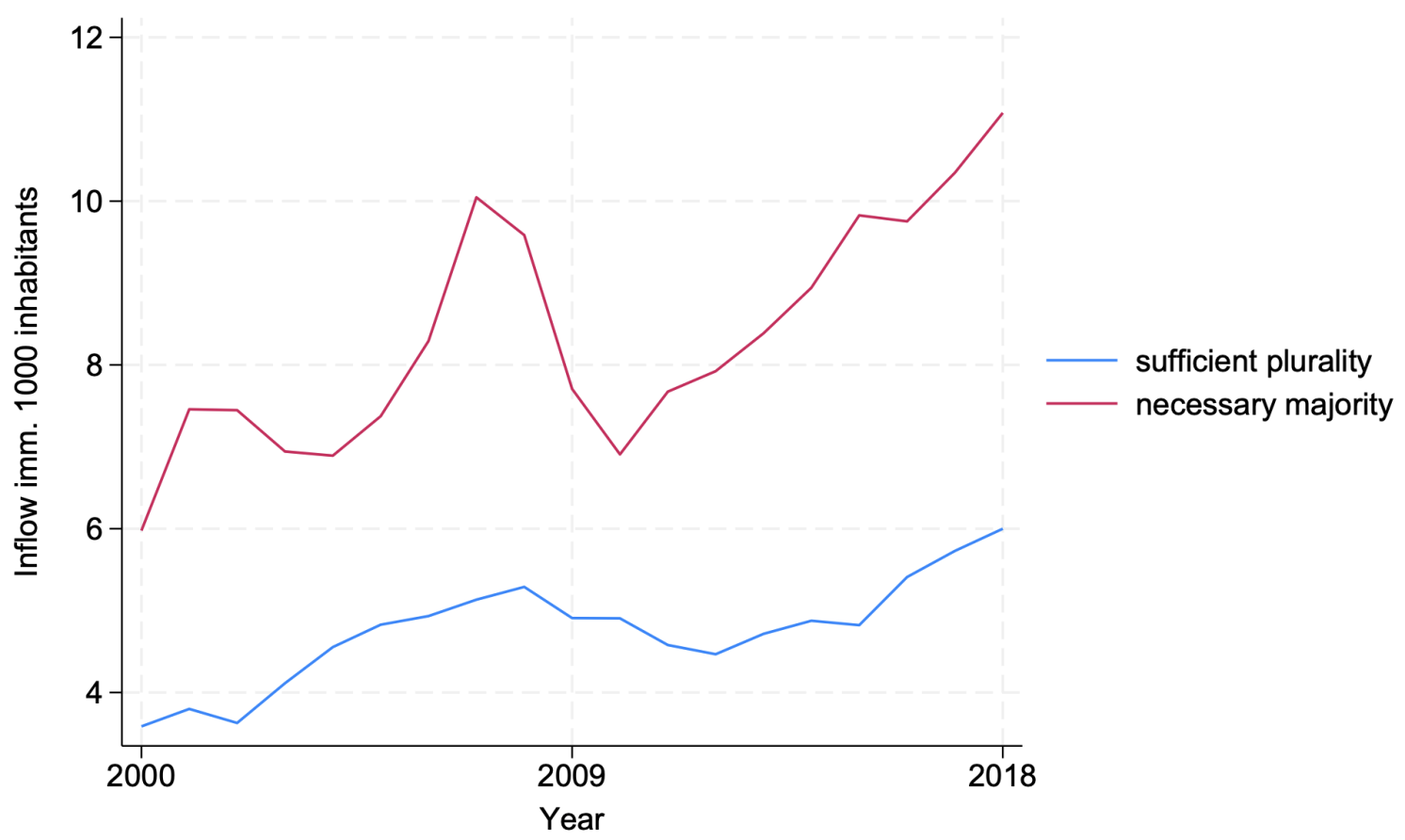

Our findings extend beyond mayoral elections and have clear implications for parliamentary systems. A straightforward extension of our model suggests that countries electing their parliaments through sufficient plurality systems (e.g. ‘first past the post’) tend to adopt more restrictive immigration policies than those using necessary majority ones (e.g. pure proportional representation). This prediction is consistent with the cross-country evidence in Figure 5, showing migrant inflows per 1,000 inhabitants across countries with parliaments elected under either sufficient plurality or necessary majority rules.

Figure 5 Cross-countries evidence: sufficient plurality vs necessary majority

Note: The data, sourced from the OECD, covers 37 countries from 2000 to 2018. The graph compares countries with (NM) electoral systems and those with (SP) electoral systems, examining the total inflow of immigrants per 1,000 inhabitants.

Conclusion

Immigration is now a defining issue of political competition. Our study shows that electoral institutions shape how this issue translates into policy. Systems where a simple plurality of votes is sufficient to win power facilitate the emergence of independent anti-immigrant parties, which leads to more restrictive immigration policies. Systems requiring an absolute majority force broader, more moderate coalitions and tend to produce less restrictive immigration policies.

As political debates continue to be driven by identity-based issues, institutional design will remain a key determinant of democratic outcomes.

See original post for references

Correlation isn’t necessarily causation. Italian local democracy is a lot less broken that American local democracy, where low turnouts and tiny pluralities are the norm.

The countries on the bar graph mean exactly what? The ones with heavy immigration such as Luxembourg, New Zealand, Switzerland, Iceland, Austria, etc. suffer from demographic issues that drive demand for immigrant labor — my own daughter participated in New Zealand’s “Working Holiday” visa program to work in a high-end shop in Queenstown that was entirely staffed by temporary visa-holders.

The theory is exactly the same if you replace “immigration” with any other issue. If you only need a plurality to rule, single-platform candidates/parties will present themselves. If you need a simple majority, then single-issue candidates/parties must join coalitions or merge.

The question then becomes – why do the authors focus on immigration rather than any other issue?