Yves here. This post gives a useful overview of the profile of subsidies provided by China’s government, not just national but also local. Despite the headline focus on industrial subsidies, the authors also show the level of disaster relief and social welfare subsidies, and counter-intuitively, agriculture gets the biggest subsidies in aggregate.

By Shuhui Xiang, PhD candidate Geneva Graduate Institute, Xinran Yin, and Yuan Zi, Assistant Professor in Economics Geneva Graduate Institute. Originally published at VoxEU

China’s industrial policy has become a central flashpoint in global trade debates, yet systematic evidence on what China actually does remains scarce. This column reveals five key findings from a new database covering China’s WTO subsidy notifications from 2001 to 2022: (1) direct fiscal support stabilised around 0.8% of GDP after 2008; (2) China is an active subsidy user with striking policy persistence; (3) FDI-promoting subsidies have declined while industry-specific and innovation-focused support has risen; (4) wealthier, more open provinces provide more local subsidies; and (5) agriculture dominates by value while manufacturing subsidies are modest. These patterns reveal how China’s subsidy strategy has evolved from attracting foreign capital towards technological self-reliance.

China’s rise as a manufacturing powerhouse has been accompanied by persistent debates about the role of government intervention (e.g. Aghion et al. 2015). While certain policies, such as tariffs and FDI regulations, are well documented, systematic evidence on China’s broader industrial subsidy landscape has remained elusive. This gap matters: subsidies are among the most direct and powerful tools governments use to shape economic activity, and understanding China’s approach is essential not only for trade and development policy, but also for debates on geopolitics, industrial competition, and technology security.

In a recent paper (Xiang et al. 2025), we address this gap by digitising and analysing China’s official subsidy notifications to the WTO from 2001 to 2022. This represents the first systematic, non-estimated dataset of Chinese industrial subsidies based on authoritative government sources. The database covers 1,256 unique programmes – 260 at the central level and 996 at the local level – including direct financial appropriations, grants, interest-discount programmes, and tax incentives. After cross-checking notifications against original domestic documents, we document five findings.

Fact 1: Subsidies Incidence Has Expanded, but Direct Fiscal Support Stabilised

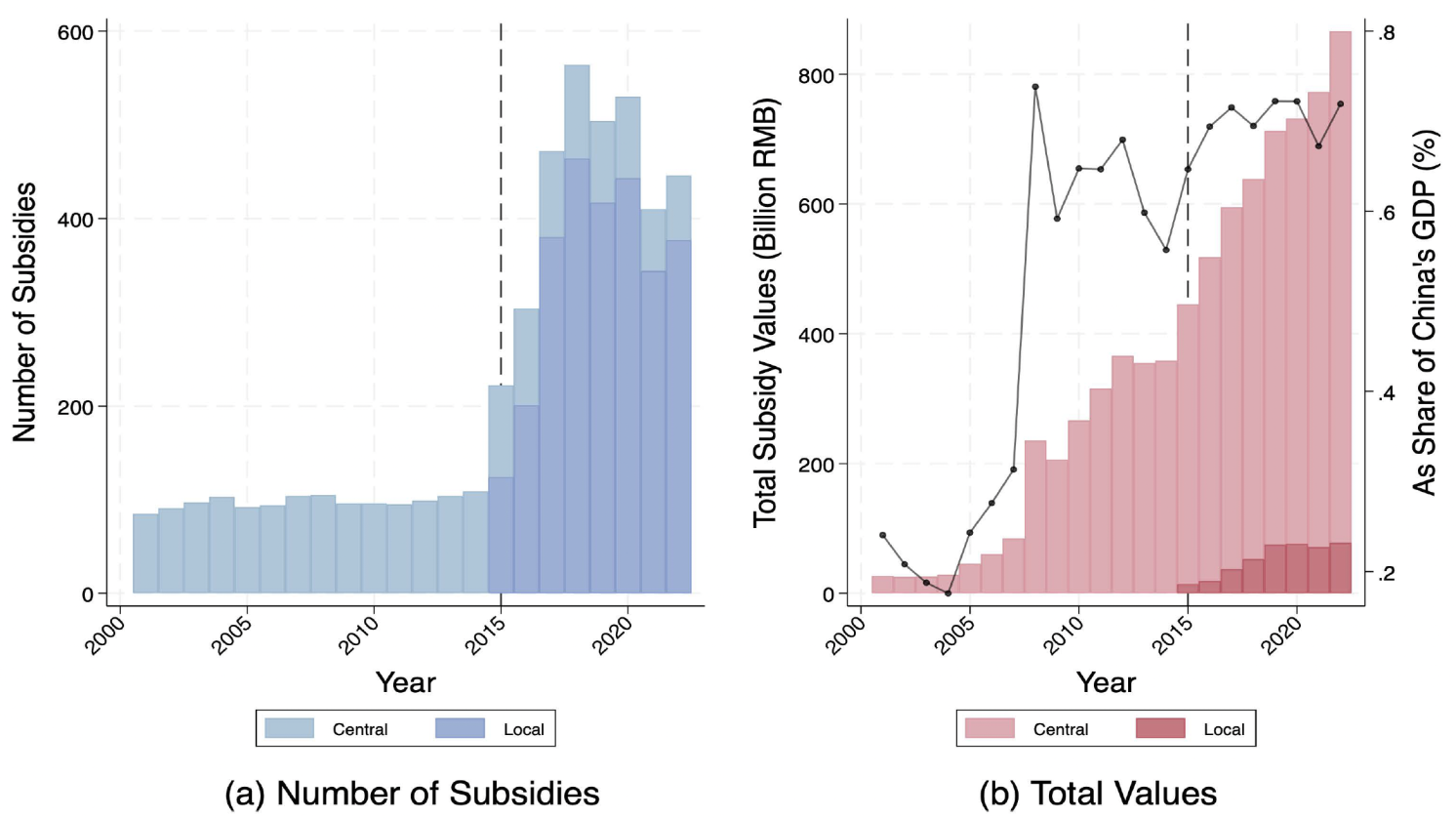

China’s subsidy incidence has increased over time, with the number of active programmes rising from 85 in 2001 to 446 in 2022. However, the post-2015 jump largely reflects a change in reporting methodology, as China began including sub-central programmes following an EU request – though local subsidies amount to only a fraction of central government support (Figure 1a).

More telling is the trajectory of subsidy values, as shown in Figure 1b. Direct fiscal support rose sharply after 2004 – coinciding with a major expansion of rural support policies – peaked around 2008, and has since stabilised at approximately 0.8% of GDP. This figure aligns broadly with OECD estimates and suggests that while China remains an active user of subsidies, the scale of direct budgetary support has not continued to escalate.

Figure 1 Annual trends in Chinese subsidies

Note: Panel (a) reports the yearly count of central and, from 2015 onward, local subsidies. Panel (b) shows their total value, with the line chart indicating subsidy values as a share of GDP (right axis).

Fact 2: China Subsidizes More Than Its Development Level Predicts, with Remarkable Policy Persistence

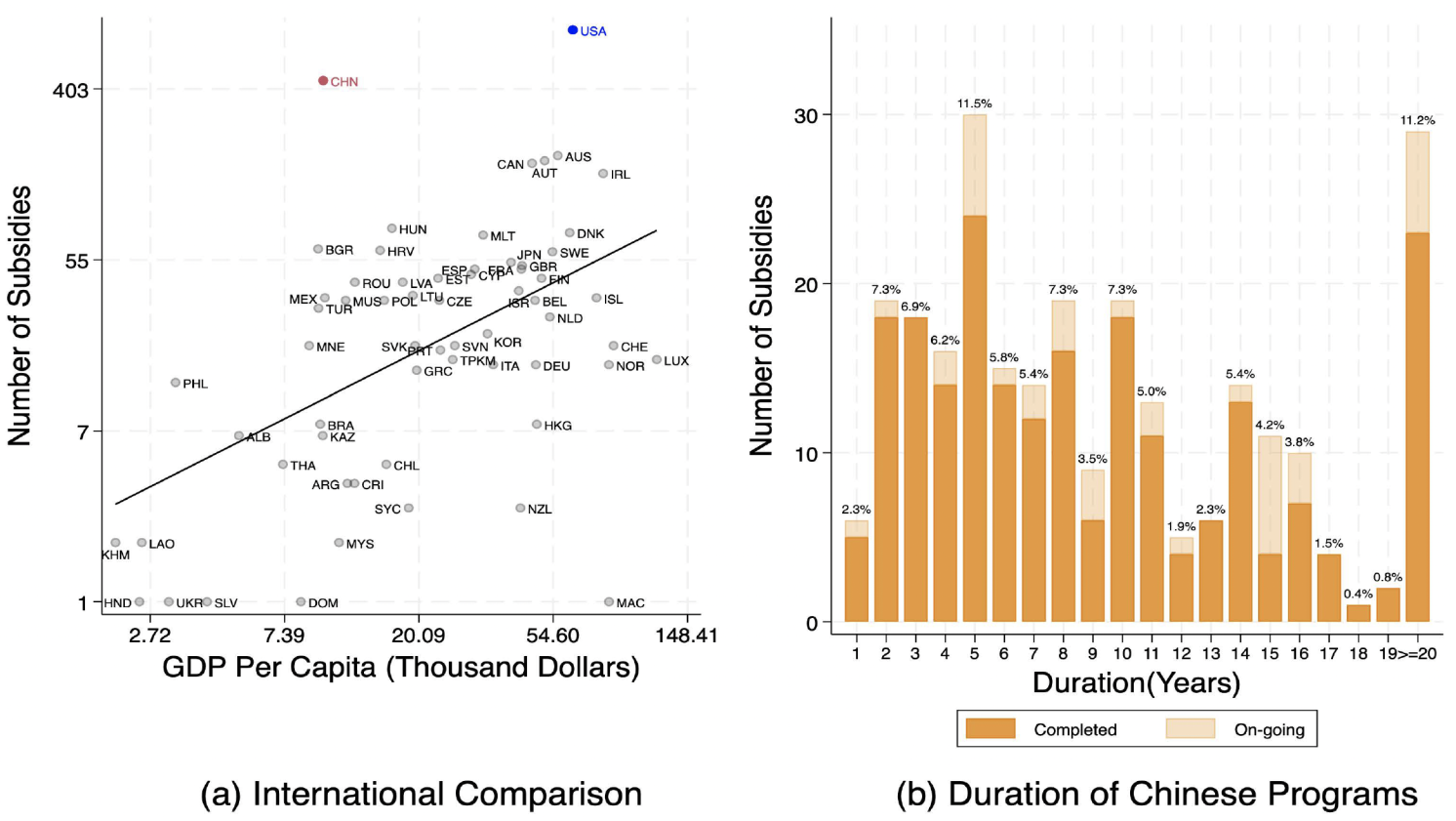

As shown in Figure 2a, comparing subsidy notifications across WTO members reveals a notable pattern: plotting the number of subsidies against GDP per capita in 2019–2020, China (and the US) employs far more programmes than its income levels would suggest.

While some less developed countries may underreport their subsidy practices, even more notable is the persistence of Chinese programmes visualized in Figure 2b. The average central subsidy programme lasts more than ten years, with approximately 10% persisting for 20 years or longer. This durability reflects a long-term strategic approach where subsidies function as sustained investments rather than temporary interventions, pointing to strong institutional commitment and policy continuity across political cycles.

Figure 2 Duration and number of subsidies

Note: Panel (a) plots the number of subsidies against GDP per capita in 2019, with variables shown on a logarithmic scale and axis labels reported in levels. Panel (b) plots the duration of Chinese central subsidy programs active between 2001 and 2022.

Fact 3: From FDI Promotion to Technological Self-Reliance

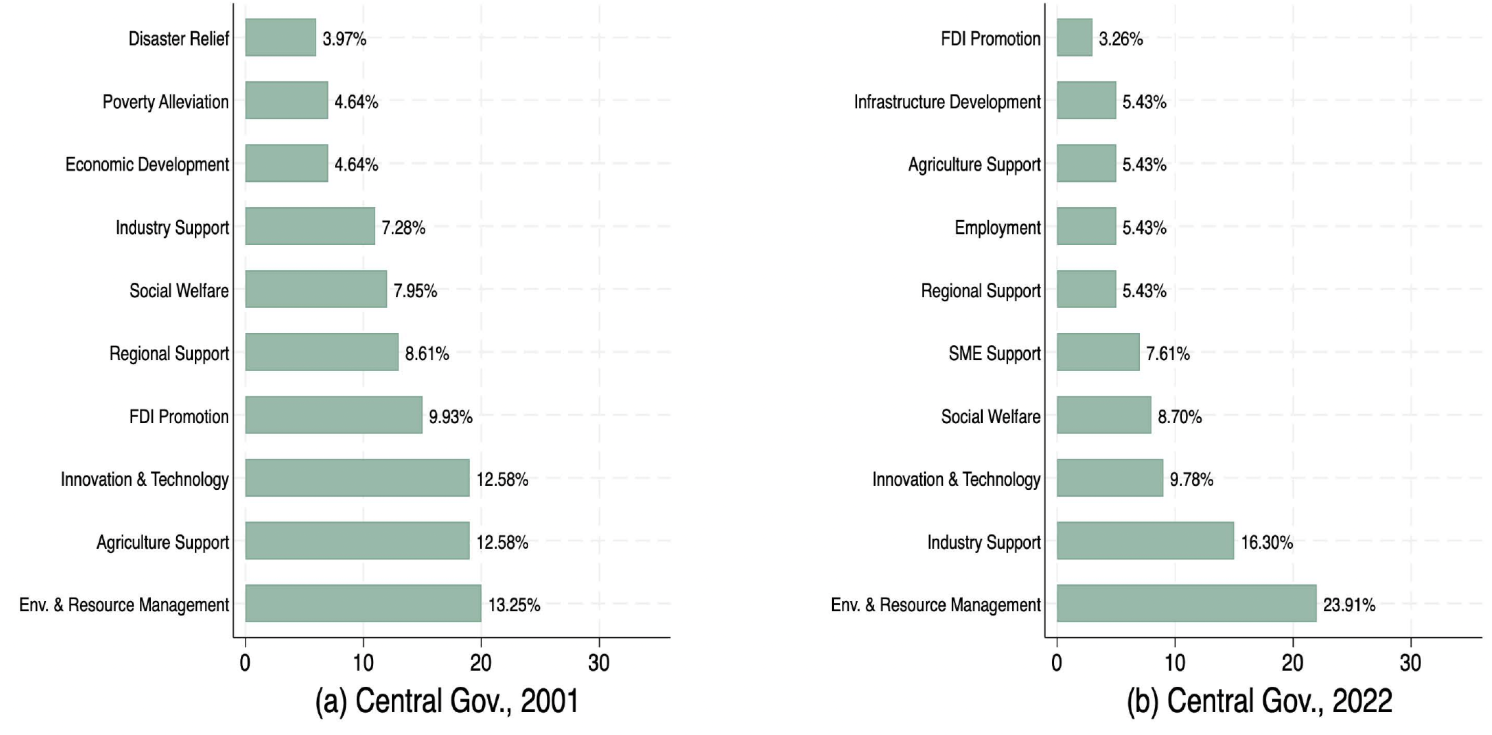

The objectives of Chinese subsidies have shifted markedly over two decades. As depicted in Figure 3, programmes promoting foreign direct investment accounted for nearly 10% of central government subsidies in 2001 but declined to just 3.3% by 2022. Conversely, industry-specific subsidies more than doubled, rising from 7.9% to 16.3% over the same period. Innovation and technology have consistently received a sizeable share of subsidies.

Figure 3 Changes in objectives, 2001 vs 2022

Note: Panels (a) and (b) report central government subsidy incidence in 2001 and 2022, respectively. Percentages indicate each objective’s share of total subsidies for the given year and government level.

This reallocation reflects China’s strategic pivot from trade and FDI liberalisation towards technological self-reliance and industrial sovereignty. Viewed in this light, the earlier openness to foreign investment may have been an intermediate stage rather than an end in itself. The timing and scale of this shift both responds to and helps explain intensifying trade and technology tensions with Western economies.

Fact 4: Wealthier, More Open Provinces Subsidize More

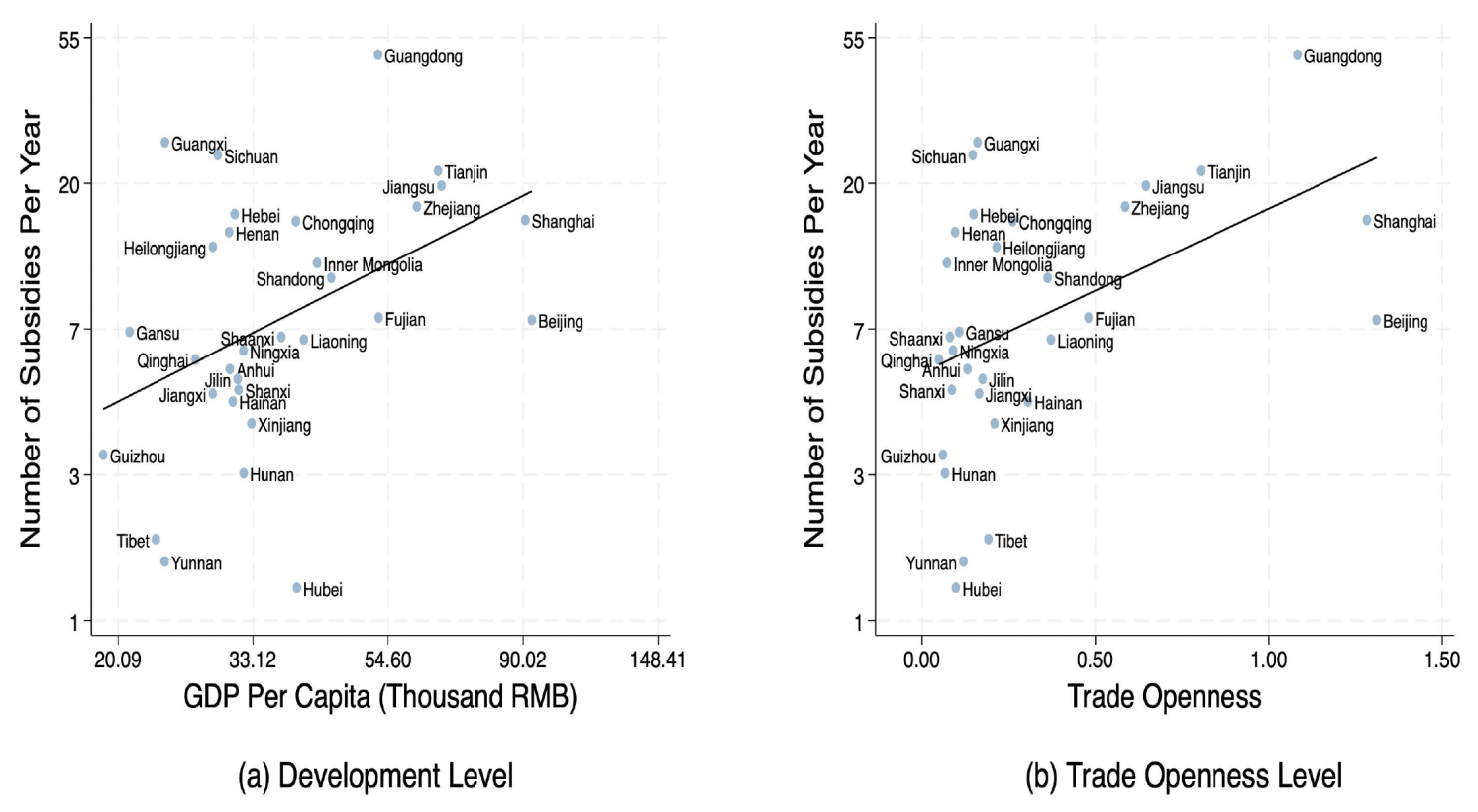

The data also allow us to examine sub-central subsidies reported since 2015. In Figure 4, we find that wealthier and more trade-oriented provinces provide significantly more local government support. This pattern suggests that local subsidies may reinforce rather than reduce regional disparities within China. It mirrors broader fiscal disparities, as the richest regions spend several times more per capita than the poorest.

Figure 4 Number of subsidies and local government indicators

Note: Panel (a) plots average number of subsidies (2015–2022) against average GDP per capita (2010–2014), and Panel (b) against trade openness across 31 provinces. Both variables are shown on a logarithmic scale with pre-log axis labels.

Fact 5: Agricultural Subsidies Dominate by Value

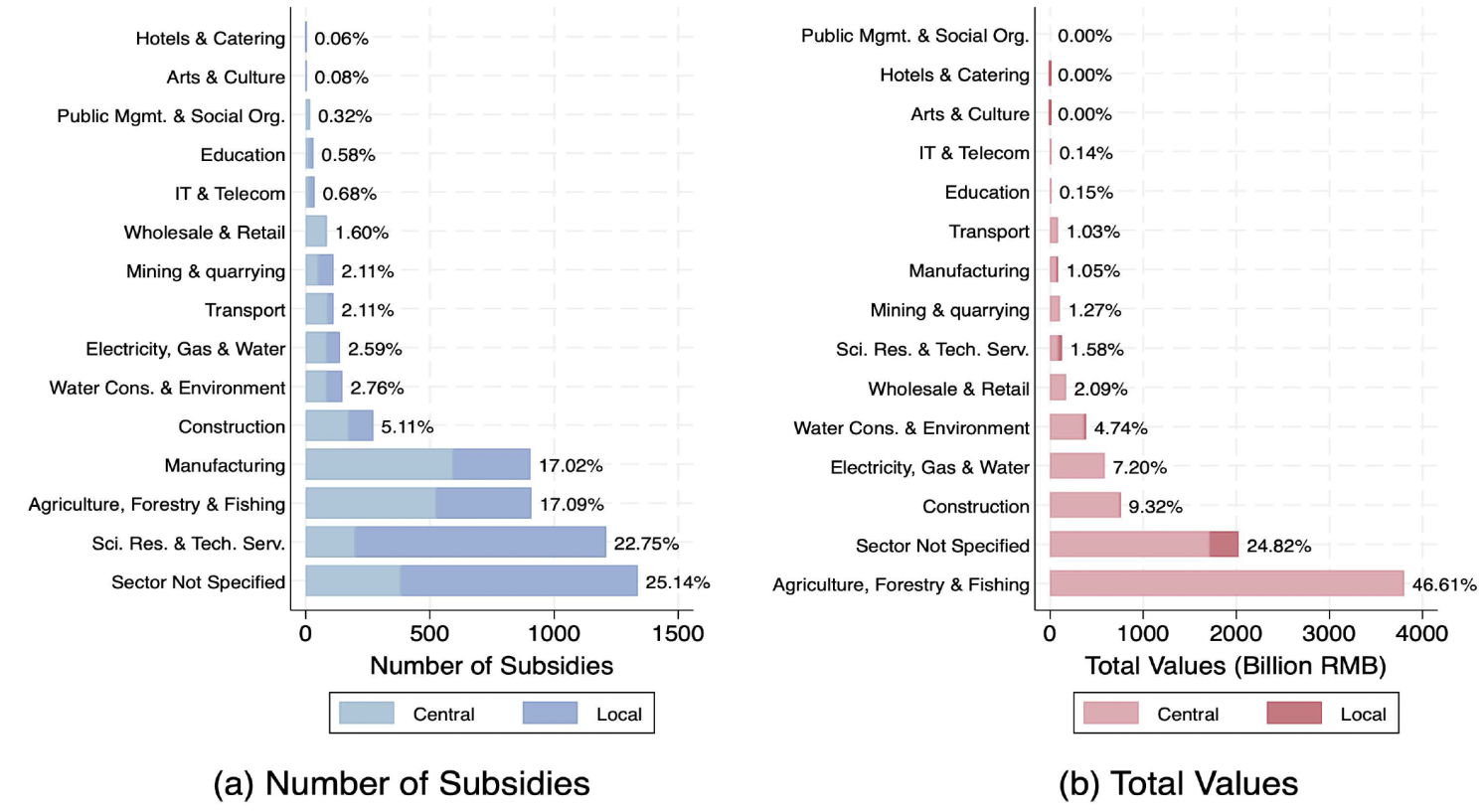

Finally, Figure 5 suggests that measuring subsidy by count versus value yields a very different picture. By programme count, scientific research, agriculture, and manufacturing are the most frequently subsidised sectors. However, the value distribution tells a different story. Agriculture dominates, receiving nearly 40 trillion RMB over 21 years – approximately 47% of total funds. Construction ranks second, reflecting China’s emphasis on infrastructure investment.

Figure 5 Subsidies by sectors

Note: Panel (a) reports each sector’s share of the total number of subsidies, and Panel (b) reports each sector’s share of total subsidy value.

Notably, direct manufacturing subsidies are relatively modest, both in total value and per-programme terms. On average, a manufacturing subsidy is less than twice the size of one for R&D and under 1/20th the size of one for agriculture. China’s decentralised, small-scale support for manufacturing contrasts with perceptions of large-scale ‘big push’ interventions. This pattern aligns more closely with recent research emphasising incremental approaches to technological upgrading (Juhász et al. 2024) and flexible policy toolkits (Bloom et al. 2019).

Conclusion

Our analysis of China’s official subsidy notifications reveals a more nuanced picture than typically portrayed in policy debates. While China is indeed an active user of industrial subsidies, direct fiscal support has stabilised since 2008. The strategic focus has shifted decisively from attracting foreign investment towards promoting domestic innovation and technological capabilities. Manufacturing subsidies, contrary to common perception, are relatively modest and decentralised.

These findings carry implications for both trade policy and development economics. For trading partners concerned about Chinese subsidies, the data suggest focusing on the evolving objectives rather than just the scale of support. For developing countries looking to China’s experience, the evidence points to sustained, flexible approaches rather than one-off interventions.

We hope this database, along with other recent efforts (Juhász et al. 2022, Fang et al. 2025), will enable further research on industrial policy, including comparative analyses with other countries and systematic evaluations of subsidy effectiveness.

See original post for references

There is a certain level of motte and bailey argumentation in this article- it takes a very narrow variable (direct industrial support) and then extrapolates it to the wider question of total State support for industry or agriculture. In reality, in all countries, not just China, State support is generally much wider and very difficult to define – from education inputs, direct infrastructure aid, subsidised land or inputs or ‘special deals’ with loans, tax breaks, etc.

Beijing in general does not provide much more direct support to industry or agriculture than most other national governments, but China has a particularly decentralised policy whereby local and regional governments are pretty much given free rein to support local developments (although as other research indicates, there is a strong bias to Upper Tier, politically well connected cities and regions). The interrelationships between ‘private’ companies, SOE’s, banks and other sectors are very complex and opaque to outsiders. There is nothing uniquely Chinese about this (it can apply to Germany and Japan too), but most studies indicate that there are an enormous range of supports/subsidies provided at this level, with low interest loans and discounted land being probably the most important. The studies I’ve seen indicate a level of support at around 2.5%, or possibly much higher (some say as much as 10%). As always with China, its as much about educated guesswork as anything else.

I read a Western report on the Chinese dominance in shipbuilding that concluded that the Chinese reached their position by offering enormous subsidies to the industry. What were the nature of those subsidies ? The vast majority of the value was in the low-interest loans offered by government-linked development banks to Chinese shipbuilders. But why does a Western analyst get to decide that Chinese currency loans from Chinese banks to Chinese industrial concerns constitute subsidies and not investments ? If Western countries don’t like it, they could start their own industrial development banks rather than complain that credit allocation based on any principle other than the enrichment of financial services industry executives is unfair.

That suggestion is only partly right and it sort of understates how difficult this would be to put in practice.

China’s shipbuilding industry(which considers a Commanding heights sector like most other ML states) is dominated by SOEs, meaning those low interest loans you mentioned largely flow from state owned banks to state owned shipbuilders. That’s more than just industrial policy choice as you’d see in the west, its a political and institutional arrangement. In most liberal democracies, that level of sustained credit flows from public banks to state owned firms in capital intensive sectors(which can be magnets for activist(environmental, labor) criticisms) would be politically fractious, legally contested(making the executive accountable to an independent judiciary untethered from strategic concerns has its costs and consequences), not to mention the inherent vulnerability of such state actions to electoral reversals.

Also, industrial development banks address only one constraint, access to patient capital. Shipbuilding dominance also relies on factors that Western societies have allowed to atrophy over the last couple of decades. Things like control over industrial land(this can be easier to manage than most), tolerance for large scale heavy manufacturing(political coalitions that champion industrial policy tend to host the biggest critics of its outcomes), disciplined labour systems(Vocational and technical education is heavily prioritized by the Chinese state also, China is adept at using incentives and propaganda to discipline its vast workforce, something the relatively rights minded westerner would find offensive), and a social acceptance of production as a national priority rather than a residual activity. Korean and Japanese govts spent decades building these capabilities under very specific historical and social conditions.

Simply replicating the financial instruments without the surrounding institutional, ownership and cultural framework will not reproduce the desired outcome. So while credit is necessary, its not enough.

I basically agree with everything you said. My intent was not so much to suggest that all Western countries have to do is found a new ecosystem of national industrial development banks and simply through doing so they can revitalize their manufacturing sectors, but rather to emphasize that a lot of the Western complaints about Chinese subsidies are simply sour grapes over the fact that Western neoliberalism fails where Chinese national industrial policy succeeds. When you look to the details, more often than not, the substance of Western discontent is that China offers credit at supposedly “non-market” rates to companies operating in strategic industrial sectors. Who decides what constitutes a “market” interest rate on a loan from a state-owned bank to a state-owned ship-builder ? There’s really no such thing. The Chinese government can offer credit denominated in RMB just as easily at an interest rate of 0.1% as it can at 1% or at 10%.

I don’t mean to say that modern Western economics has turned into a theology, but it’s true that more than half of Western economists remind me of theologians. Their only real skill seems to be worshiping deities like Adam Smith or Hayek.

Don’t people realize China is a country operating under the scientific socialism of Marx and Lenin – of course a socialist government is going to “subsidize” industry and every other socially necessary economic undertaking; the socialism of China kicked the living crap out of the decrepit capitalism of the west that delivers such boners as Trump and the ignorant EU crew all of whom preside over economic destruction!

You are partly right, but I do disagree on two key points.

First of all, the idea that “China has a particularly decentralised policy whereby local and regional governments are pretty much given free rein” kind of conflates administrative decentralisation with political decentralisation(China has a Marxist Leninist Party state). While China is administratively decentralised, often more so than the US, it retains a Leninist party structure allows it to centralize political authority. Provincial and municipal governments dont constitute autonomous power centres, they explicitly operate within a unified Party hierarchy, with its cadre promotion, policy priorities and red lines all set centrally but the State Council. If anything, political centralization has only increased since reform and opening, even as their administrative experimentations have continued.

Also, the claim that “there is nothing uniquely Chinese about this” and that it can be equally applied to Germany or Japan is objectively wrong.

The Chinese state possesses a level of political authority, institutional reach and coercive capacity over land, capital and its strategic sectors that countries like Germany and Japan simply do not. In both of those countries, private enterprises continue to dominate key strategic industries that the state has to negotiate, regulate or incentivize as opposed to having a direct line of authority to command. That alone shows a fundamental difference in political economy. This doesn’t mean that the state acts unilaterally every single time, the management in those SOEs do discuss and negotiate with Local and Provincial govts, they have to inorder to function effectively, but the primacy of the state is never under question.

So, These are not marginal distinctions. They speak to the core of how policy is formulated, enforced and sustained over time.

Treating China as a variation of a coordinated market economy(like the French or even the Korean) rather than as a Leninist party state leads to the kind of analytical slippage you’ve made.

You will find that actually, Japan specifically did have a very high degree of political authority and even coercive capacity over its private enterprises, right down to the one party state. Chalmers Johnson’s great book from 1982, “MITI and the Japanese miracle: the growth of industrial policy, 1925-1975” goes to extensive length in documenting just how these functioned on the whole via the extensive “bureaucratic-industrial complex” and “administrative guidance”. MITI (the all powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry) for example had nearly total control of all foreign exchange in Japan until the mid 1960s. If you were a firm doing foreign business, all your foreign exchange earnings had to be converted to Yen with MITI, and likewise with Japanese firms looking to import foreign goods, MITI essentially had veto power over their purchases by denying them foreign currency allocations. Also good luck trying to license or import foreign technology without MITI’s say-so. That is just the start of the kind of economic-government planning that characterised Japanese development in the post WW2 era. They were the pioneers for the Asian State-Led development model that China has adopted.

Your point on having to look at the broader political economy is spot on. That’s where trying to understand the Chinese economy should really start, and where a lot of the comparisons with WTO subsidies and the like kinda get lost in the weeds.

Indeed!

https://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue23/Locke23.htm

I have real dificulty distinguishing between the adminstrative and the political in China, or in any other context for that matter. My understanding is that the promotional route to higher levels of political power in China is through a continuous demonstration of technical and administrative skills along with the ability to generate and implement plans within the extremely broad parameters of national, ie, party, policy. The notion that a “Marxist-Leninist state” (or a “Confucian state with a tinge of Marxist-Leninist thought”) is somehow fundamentally different from other approaches to governing a rapidly growing Listian economy with a high degree of indicative planning and target setting seems really off-key and of limited relevance apart from the fact that whatever they do, they do really well.

Yes, reading through this article the question I kept having was “what is a subsidy?”, because trying to make the analysis they are doing by constraining the definition of state development support to a very narrow “direct subsidy” severely limits the analysis, almost makes it worthless outside of the very narrow comparison of WTO subsidies between China and the Western ShitLib countries. I might even say it’s disingenuous. These kind of analyses don’t tell you very much at all if you aren’t taking into account how China’s political economic system functions to promote industrial policy as a whole. Subsidies *are just the start* of industrial policy (and not even the most important part).

The understanding of industrial policies and developmental states isn’t new or novel either, anyone that cares to look at Japan and the other Asian countries that industrialised in the 20th century will find the parallels. As Japan showed so very well, one can have EXTENSIVE state intervention in an economy with very little in the way of direct subsidies or even things like state enterprises. Japan during it’s economic rise had essentially no state owned enterprises in manufacturing (unlike Britain or France), and the share of public spending was either the lowest or second lowest, consistently, in the OECD. And yet if you look at the contemporary literature, you see “Japan, Inc” and even comparisons with centrally planned economies.

The mistake, as always, was separating “political” from “economy”.

‘The mistake, as always, was separating “political” from “economy”.’

Correct.

Claiming that they are separate was always a lie.

So — cui bono?

That may even explain the discrepancy betweens figure 3 – 5.43% in 2022 and figure 5 – 46.61% wrt Ag subsidies. The definition may have changed between the two figures? In any case, as this is a major conclusion, it should have merited more discussion – this piece should have been reviewed by Shuhui Xiang’s professor (Yuan Zi) before submission.

Secondly, a good question is where the professor’s funding arises – which NBER discussion papers do not insist on showing (as it could reveal conflicts of interest and institutional bias). The professor’s web page lists some peer-reviewed papers that list the European Research Council – so no smoking gun there.

I disagree with the premise of this article. It implicitly assumes that China operates within the same political-economic framework as advanced capitalist democracies and is thus3 assessed by comparing levels of “subsidies” or “direct support” to industry and agriculture. This entire framing is fundamentally misplaced.

This concept of subsidies presupposes a liberal market baseline where land, capital, labour, and technology are mostly in private hands and are primarily allocated through markets, with the state intervening episodically or even barely to correct outcomes. China’s Marxist-Leninist party state system does not function in this format. They’ve collectivized land ownership where the state controls all urban land(and rural land is under the collective ownership) so when you hear about land sales by local govts, they are just selling the lease hold rights, The dominance of state-owned enterprises in strategic sectors like heavy industry, the prevelance of state-owned banking system, and nationally coordinated labour and education policies(where secondary and tertiary education implicitly prioritizes STEM and Vocational education at the expense of HSS or academic freedom) place the state upstream of the market itself.

Under these conditions, distinguishing between “normal market activity” and “state support” becomes very hard.

To summarize, the Chinese state operates with a relatively high degree of unity of purpose across its central, provincial, and municipal levels, enabled by its party state system. This allows it to exercise extraordinary levels of control over land, labour, and capital(something none of their competitors can do without sparking a political crisis). Under these conditions, a rather narrow assessment thats focused solely on industrial subsidies cannot and will not provide a clear or accurate picture of state assistance to industries.

Sources:

1. Pg no. 63 How China Works_ An Introduction to China’s State-led Economic Development

2. https://wid.world/www-site/uploads/2024/11/WorldInequalityLab_WP2024_24_The-Making-of-China-and-India-in-21st-Century_Final.pdf

The biggest subsidy China provides is a low cost, decent, lifestyle. Clean affordable public transportation, affordable, non financialuzed housing, high quality inexpensive food. Affordable health care. Early retirement. High quality urban infrastructure. 900million out of poverty. It seems to me that this subsidizes the lower wages on the job.

They are not perfect but they are moving in the right direction.

Meanwhile in the class war west, the oligarchs are grabbing what they can while the whole thing goes down the drain.

Chinese universal care is at a very basic level.

You are right it is at a basic level, but my understanding is that it has been improving quite rapidly. Remember China until quite recently was a very poor, then poor, and now near middle-income country. The social welfare system has been going in the right direction but is not where China aims to be in the future. The health indicators show this.

Yes. Both China’s life expectancy and healthy life expectancy is slightly longer than America’s, with a fraction of US’ per capita GDP and income. The notion that China has a very poor welfare system is somewhat outdated.

Education and training are also key factors.

This is the essence of Michael Hudson’s analysis of the initial project of industrial capitalism — that the function of the state is to lower the cost of living by minimizing “overhead” costs of social reproduction. Initially this meant eliminating the feudal privileges and land rents in the hands of the aristocratic land owning class, thus lowering the cost of living for the working class and thus the cost of labour for the industrial capitalists.

The emergence of the parasitic FIRE sector has reintroduced the equivalent of the old feudal rents. Under such circumstances deindustrialization and immiseration of working people follows.