On one of his YouTubes, Gonzalo Lira and I discussed what I called belief clusters, that those who held one set of views were assumed to subscribe to a related set of opinions. A noteworthy example is how nearly all the anti-globalist commentary community (at least as on YouTube and Substack) hew to simple-minded black and white stories about the the brutal and retrograde US led hegemony, desperately trying to hang on to dominance, is opposed by a virtuous Global Majority seeking to establish a fairer new order. Part of this stereotyping is to contrast the US’ colonial and predatory actions towards other countries with China’s supposedly beneficial or at least benign economic posture

Sadly, we think the degree of difference, based on what we have seen here in Thailand and the example of Africa shows, is more like the distinction between Team Republican and Team Democrat in the US. As Lambert put it,

The Republicans tell you they will knife you in the face. The Democrats say they are so much nicer, they only want one kidney.

What they don’t tell you is next year, they are coming for the other kidney.

Admittedly, the US under Trump has become so unabashedly piratical that just about anything else looks good by comparison. But “good by comparison” should not be confused with good. Some commentators are coming to this recognition, as we discussed long form in “BRICS Are the New Defenders of Free Trade, the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank” and Support Genocide by Continuing to Trade with Israel.

Today, we will rely heavily on an in-depth story from Patrick Bond, professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology, in Africa deindustrialises due to China’s overproduction and Trump’s tariffs. Note that this is posted at the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt site, which is firmly anti-neoliberal and anti-colonial, as well as Marxist leaning.

Bond’s discussion of China relies on in-depth analyses and local readings, such as the book The Material Geographies of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by Elia Apostolopoulou, Han Cheng, Jonathan Silver and Alan Wiig , world-systems sociologist Ho-fung Hung, and Irvin Jim of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA.)

We are quoting Bond liberally in part because his argument is chock full of supporting information, and also because he regularly and explicitly counters the views of Vijay Prasad, with Bond carefully explaining why he depicts Prasad as a China optimist.

I am sympathetic with Bond’s position based on what I have seen in my comparatively short time in Southeast Asia. The English language press goes to some lengths to be inoffensive, which means hewing to well-accepted view. It has sometimes taken up complaints I have heard from locals of predatory Chinese business practices, such as zero dollar exports and zero-dollar factories. There was additional unhappiness after the Liberation Day tariffs kicked in, with China diverting shipments to Southeast Asia, not just in an apparent attempt to evade the US tariffs via trans-shipments (something the Trump Administration sternly warned area governments to prevent, not that they can readily do so) but also as a form of dumping. This is occurring despite considerable family and commercial ties between the Thai elite and important interest in China. One would have to think governments and enterprises in Africa would be less well equipped to handle challenges like these.

We’ll give only a short recap of the Trump-created damage since it is generally better known and hews with the priors not just of anti-globalists but also Trump opponents, and then turn to the less-well understood profile of Chinese exploitation. A reason China’s conduct may be less well understood is that it may be mistakenly analogized to the Africa/developing world practices of the old Soviet Union. The former USSR, unlike China, had little need to secure resources and did not have a profit motive even if they did want to secure other benefits from their support of developing countries. Contemporary China is not in the same position.

Trump’s policies have unquestionably harmed Africa. Trump and his white supremacist sidekick Elon Musk ended most had wiped out most U.S. emergency food, medical and climate-related support for Africa, with South Africa getting the extra kick of extra contract cuts. On the trade front:

Then came Trump’s devastating tariffs – in February, April and again in August – followed by the September demise of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) which since 2000 had given dozens of African countries duty-free access to U.S. markets. Notwithstanding a deeper context of dependency relations associated with AGOA – for as political economist Rick Rowden points out, “gains were largely due to African exports of petroleum and other minerals, not manufactured goods” – these latter trade-curtailing processes were exceptionally damaging, wiping out 87% of auto exports from South Africa in the first half of 2025.

The World Bank concluded of 2025’s tariff chaos, “industry-level impacts may be significant in global value chain–linked activities, notably, textiles and apparel as well as footwear (Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, and Mauritius) and automotive and components (South Africa)… Loss of the AGOA would sharply reduce exports to the United States. On average, exports would decline by 39% if a nation were suspended from AGOA benefits.”

Demand from the rest of the West is set to fall, thanks to new European regulations plus weak growth.

A must-read, detailed section of Bond’s article documents the extent and severity of China’s overinvestment/overcapacity problem, depicting it as the most prominent part of a classic Marxist capital overaccumulation. He describes in detail how, starting in the early 2010s, the Belt & Road initiative allowed Chinese companies to remedy their in-country overproduction problem by expanding along its routes.

A representative part on how the global overproduction problem is primarily a Chinese one:

Mostly though, excess capacity is the core signal, as some crucial sectoral examples show:

global steel output of nearly 1.9 billion tonnes in 2024 contrasted to 2.47 billion tonnes of capacity (i.e., 76% capacity utilisation), with a rise of another 10% excess capacity estimated in 2025, to 680 megatonnes;

in chemicals, Bloomberg News reported earlier this month, “A wave of new Chinese petrochemical plants is raising fears of a deluge of exports that will put pressure on other producing nations that are already struggling with oversupply” due to “seven massive petrochemical hubs… creating a global glut that could swell even further if more planned plants come online” at a time, in 2025, polyethylene output rose 18%;

China’s annual vehicle production capacity – carrying either internal combustion engine or electric motors – was 55.5 million vehicles/year capacity in 2024, but was only half utilised (just 27.5 million vehicles were produced that year), while in 2025, Chinese output was expected to reach 35 million (still a low capacity utilisation), displacing other economy’s sales and leaving the world with increased idle capacity, as global vehicle sales languish at 90 million;

also in China, “The root cause of the cement sector’s current difficulties lies in the long-standing problem of overcapacity, which has now been amplified by weaker market demand” since 2021 “due to declining property investment and a slowdown in infrastructure construction,” according to the China Building Materials Federation, and

solar photovoltaic panels generated nearly 600 GW of new power in 2024 – mostly emanating from China – but there was, at that point, more than 1,000 GW of annual manufacturing capacity, and to store the power, lithium-ion batteries were produced at the scale of 2.5 TWh in 2023, but by 2024 there was 3 TWh of capacity and projections of 9 TWh by 2030, at a time demand was expected to rise only to 5 TWh.

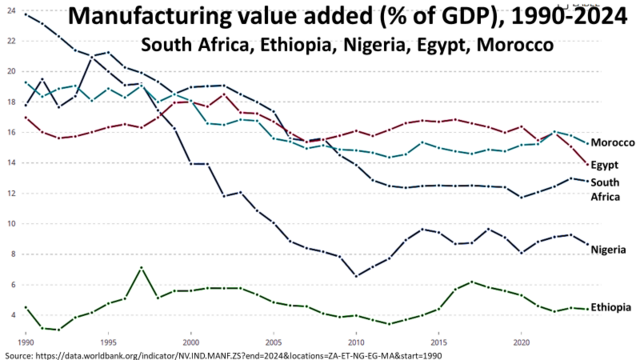

Bond describes how the countries in Africa that were most industrialized have seen the size of their manufacturing sectors fall relative to the size of their economy; even the supposed Chinese success story of Ethiopia saw gains largely eroded. Per Bond:

…there are too many instances of adverse impacts from Chinese capitalism in Africa: deindustrialisation through swamping local markets with surpluses (as NUMSA complains), especially as the displacement of Trump’s tariffs; broken promises on Special Economic Zone investments; brazen but unpunished corruption; excessive lending and then sudden cuts in credit lines; and heinous corporate behavior especially in the extractive industries, including extreme ecological damage. Each needs elaboration, in the pages below.

And one test case deserves more consideration: the rapid deindustrialisation of South Africa underway in recent months thanks to the ‘dumping’ (i.e. sale at below the cost of production) of Chinese overaccumulated capital, according not only to the government in Pretoria – which in recent months punished imported Chinese steel, tyres, washing machines, and nuts and bolts with new tariffs – but also to NUMSA (which wants the same for cars), although it is ordinarily very pro-China. In South Africa, the manufacturing/GDP ratio was 24% in 1990 and has now sunk to 13%.

Formidable Chinese product competition means the African economies mentioned by Prashad as the continent’s lead industrial production sites, plus the largest in population (Nigeria), have not improved their manufacturing/GDP ratios since that 2015 FOCAC industrialisation hype. Most such ratios, like South Africa’s, had already collapsed in the first round of 1990s-era trade liberalisation.

The optimal test case that many pointed to during the mid-2010s as Africa’s cutting-edge industrialisation site, was Ethiopia, thanks to the sudden emergence of (largely sweatshop) manufacturers mainly in Addis Ababa, whose products benefited from the new train line to the port of Djibouti, built with the assistance of Beijing. As a result of the influx of Chinese firms’ local production of clothing, textiles, footwear and other light-industrial output, Ethiopia’s manufacturing/GDP rose rapidly from 3.4% at the low point in 2012, to 6.2% in 2017.

However, that ratio subsequently fell to 4.3% in the period 2021-24. As the International Monetary Fundexplained, “The share of manufactured goods such as textiles, leather and meat product in total exports had grown to 13.5% in Fiscal Year 2018/19, from a small base, but declined sharply thereafter to around 4% in the first nine months of FY2024/25, due to the pandemic, conflict, suspension from AGOA, and foreign exchange shortages that limited availability of intermediate imports.”

Those hard currency shortages led to a major financial crisis in late 2023…As a result of the default, Ethiopia was initially not permitted to become a formal member of the BRICS New Development Bank, for potential hard-currency credit infusions (nearly 80% of that bank’s lending is in the dollar or euro), although it is scheduled to join, at some stage….

Will Beijing step in? In aggregate, Chinese aid, investment and loans to Africa have also fallen since mid-2010s peaks, which also affected states’ foreign exchange reserves. China’s own new public and publicly-guaranteed loans to Africa collapsed from $32 billion in the peak year of 2016, to $1 billion in 2022. The year-end 2025 African foreign debt of $1.3 trillion includes $182 billion in Beijing’s known public and publicly-guaranteed loans.

Bond also takes issue with the widely-accepted view that China is generous in its debt restructurings when Belt & Road borrowers have trouble meeting obligations. This is again the fallacy of seeing something that is less bad than IMF “rescues” as good. Bond describes how poorer countries like those in Africa are treated more harshly than middle-income debtors:

China’s own new public and publicly-guaranteed loans to Africa collapsed from $32 billion in the peak year of 2016, to $1 billion in 2022. The year-end 2025 African foreign debt of $1.3 trillion includes $182 billion in Beijing’s known public and publicly-guaranteed loans.

China had taken a decision in 2021, AidData researchers remind, to fund 128 rescue loan operations in 22 low-income countries facing debt distress, costing $240 billion. These included five African states – Angola, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya – among which low-income borrowers were “typically offered a debt restructuring that involves a grace period or final repayment date extension but no new money, while middle-income countries tend to receive new money – via balance of payments (BOP) support – to avoid or delay default… These operations include many so-called ‘rollovers,’ in which the same short-term loans are extended again and again to refinance maturing debts.”

The 2024 FOCAC did, however, denominate more financial flows in the Chinese currency, which could facilitate trade, alleviate forex shortages, and also lower transactions costs. Yet devils are in the details, for against all the logic argued above, according to the Centre for Global Development (which is generally neoliberal and welcomes Chinese lending):

Between 2015 and 2021, commercial creditors contributed about a third of all Chinese lending commitments over that period. These commercial lenders overtook policy banks between 2018 and 2021 … [and] are market-oriented, with loans that are more expensive and with shorter maturity than state-owned counterparts. Their need for risk mitigation, usually through Sinosure, raises the financing costs even higher. Over the next five years, a continuation of this trend where Chinese commercial lenders become an ever-larger segment of lending to Africa at non-concessional rates will only heightens the risks of debt distress.

Bond even dares raise the third rail issue (in left-leaning/anti-globalist circles) of whether China, in its quest to secure resources, is looting Africa. That’s a reasonable question given the increasing role China has played in the continent even, as we showed above, manufacturing value added has fallen in the most industrialized countries. Bond addresses the argument by China-defenders like Vijay Prasad, that Chinese firms have been competing in Africa with Global North concerns, with the result that competition has resulted in African nations getting better terms and, arguably, China is being unfairly charged with using African resources to build products often destined for first world markets. Bond makes a variant of our “coming for your kidneys over two years does look less bad than being knifed in the face” argument. From the article:

As noted above, there are usually three categories to consider, of ecological reparations due to non-renewable resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of localised pollution….

Indeed this subimperial location within global value chains makes China subject to an unequal ecological exchange critique. For behind the general need for resource extraction and (limited) processing of minerals that goes on in Africa, are scandalous conditions. Without sinking into Sinophobia, it is useful to recall some of the highest-profile cases, because Beijing simply fails to respond to the obvious need to curtail Belt and Road abuse by Chinese firms:

- in the DRC in November, Congo Dongfang International Mining leaked toxic pollution into the Lubumbashi River near the country’s second largest city, while nearby at Kalando, informal miners (75% of whom across the DRC sell their wares to Chinese buyers) suffered at least 50 deaths in a mountainside collapse that compelled the government to ban artisanal copper and cobalt mineral processing, in the wake of non-payment of billions of dollars’ worth of royalties to the government by Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Ningxia Orient, JiuJiang JinXin and Jiujiang Tanbre smelters – all within Apple’s supply chain – which in turn resulted in a major lawsuit by the Kinshasa regime and by a U.S. public interest agencyagainst the California corporation, and similar non-payment accusations were made by Kinshasa officials against China Molybdenum’s super-exploitative Tenke Fungurume cobalt mine;

- in Zambia’s copperbelt in February, negligence by Sino-Metals Leach and NFC Africa Mining caused a slime-dam break – of 1.5 million tonnes of cyanide- and arsenic-laced sludge – into the Kafue River, resulting in an $80 billion lawsuit by some of the 700,000 affected residents adjacent to Zambia’s main internal waterway and second-largest urban region;

- in the Central African Republic’s mines, there was slave-like human trafficking of Nigerians – who went unpaid for a year in 2024-25 – by Rado Central Coal Mining Company;

- in Ghana, Shaanxi Mining extracted gold in a manner that amplified the ‘galamsey’ artisanal mining crisis;

- in Zimbabwe, there are countless complaints against Chinese mines, for looting $13 billion of Marange diamonds by the military-owned parastatal Anjin (as even President Robert Mugabe alleged in 2016), for the murder of a dozen Mutare artisanal gold miners in 2020 by Zhondin Investments, for mass displacement and pollution at the Hwange coal mine by BeifaInvestments, for illegal mining in national parks by Afrochine Energy and Zimbabwe Zhongxin Coal Mining Group, and for Sinomine Resource Group’s failure to respect beneficiation requirements at the continent’s largest lithium mine, in Bikita, in addition to other Chinese lithium miners at Kamaviti, where as a result, Centre for Natural Resource Governance director Farai Maguwu alleged in late December, “Zim is the biggest donor to China, and not the other way round”;

- in South Africa, the corruption of rail parastatal Transnet by Chinese locomotive suppliers empowered the notorious Gupta ‘state capture’ family, while at two chaotic Special Economic Zones, Chinese investors included an Interpol red-listed looter of a Zimbabwean mine and two auto producers (FAW and BAIC) whose job creation and production promises were not kept; and

- in the two main oil and gas controversies in Africa, state-owned China National Overseas Oil Corporation is building a heated pipeline (the world’s longest) from western Uganda to Tanzania’s port of Dar es Salaam, and state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation’s participation (with partners ExxonMobil and ENI) invested in a long-delayed northern Mozambican ‘blood methane‘ gas extraction project, in the midst of a civil war with Islamic guerrillas that since 2017 has displaced one million people and killed many thousand – and in both cases, the ultra-corrupt TotalEnergies leads the projects.

In addition to often-extreme human rights violations, these represent obvious forms of unequal ecological exchange, in which African economies lose net wealth, even if Chinese purchases of raw materials raise levels of foreign exchange and national income, creating (low-paid) jobs and providing a modicum of royalties, taxes and infrastructure.

Typically outweighing such benefits, though, damage is not limited to local pollution and displacement, or to permanent depletion of non-renewable resources that leave both current and future generations impoverished…

On top of this damage, the extraction and processing of minerals also entail an enormous ‘social cost of carbon’ caused by CO2 and methane emissions in mines and smelters…

The latter damage will create new ‘polluter-pays’ climate debtors out of low-income African economies, if the International Court of Justice’s July 2025 advisory opinion on liabilities for socio-ecological reparations is to be taken seriously…

In sum, unless the Chinese state suddenly begins regulating its firms’ emissions and abuse of African resources and people, and finds creative ways to pay a wide range of ecological reparations, it appears extremely unlikely that a genuine industrialisation initiative will emanate from Chinese investors.

So those who want to see China as an enlightened economic power might consider recalibrating their views. One economist noted for his close connections to China has even conceded to me privately when I told him “Now that I am in Thailand, I have a vastly less rosy view of Chinese investment:”

That’s why Chinese businessmen were so widely abhorred throughout Asia. And Chinese officials even bragged to me about how cutthroat they were in their business dealings.

Bsck in the days when Wall Street was criminal at the margin, Goldman described its modus operandi as “long-term greedy”. That is probably the best gloss to put on China’s mercantilism. And don’t kid yourself. Long-term greedy is still greedy.

South Africa had high tariff walls, industrial policy and state corporations through the 1980s. All was swept away in the neoliberal era. It was de rigeur to privatize and open markets. Like the east bloc, Mexico and India, local looters began their asset stripping and acquiring concession and put out the free trade welcome mat. The railroad system in South Africa was absolutely world class and provided freight services necessary for an industrialized economy. By choice, the rail system has been gutted and rusts. In Port Elizabeth both VW and Ford have assembly plants; both those corporations have been on the ropes in the domestic and foreign markets. I can’t say with certainty, but it is probably safe to assume these are not state of the art plants. Lack of investment surely allows Chinese auto companies to dump their excess production.

All of Bond’s observations and criticisms are valid. But a country like South Africa has agency. I recall Bond called it “talk left, walk right”. Much of deindustrialization has been facilitated by South African elites that have gotten their cut in the robbery.

You seem to applaud South Africa for using“ high tariff walls,industrial policy and state corporations ”to protect its manufacturing sector, so why don’t you fairly praise the Trump administration for doing the same thing?

This is obviously a very complex and multifaceted issue, with China’s role varying widely across Africa, Asia, and South America, with temporal changes from an initial ‘naive’ stage in the early 00’s, where Chinese investors/banks were often comprehensively out manoeuvred by local elites (especially in Latin America), to the current situation, whereby Beijing seems to have placed much stronger controls on bank lending outside China. However, it is clear that the manner in which Chinese investments have been structured can be very tempting to local elites (in particular the promises of quick construction outcomes), while leading to often catastrophic long term financial results. One of many examples is the Jakarta-Bandung HSR line, where a much more financially sensible Japanese proposal was sidelined, leaving the Indonesian government with an extremely expensive loss making line which is likely to bleed money for many years to come. Beijing has usually been willing to ‘restructure’ debts, but invariably this involves digging its own banks out of trouble while leaving the biggest chunk of the debts for the receptor country.

As for Africa, its been very clear to anyone paying attention that China’s investments follow the classic colonial pattern of ‘persuading’ the local country to provide backing for loans for investments which are entirely in the favour of the loanee. Chinese backed investments invariably involve almost entirely Chinese workforces (even down to the security details) to put in place infrastructure or industry that benefits China primarily, while increasing African debt levels. Or put another way, African countries take on the financial risk, while China takes any profits. There may be some benefit to African countries in being able to leverage better deals by having more competition between investors, but there is at present very little evidence of this producing real benefits at a local level. The extreme reluctance of Chinese companies to train and hire local staff ensures African countries will maintain their subservient position in the relationship.

I’ve been going through the links in the quoted section of the Patrick Bond article in regards to his accusation about BRI human rights and environmental abuses. The linked articles are there to support Bond’s critique and a couple of them are very damning. But even while checking how much the linked sources substantiate his accusations, two articles jumped out:

https://www.newsghana.com.gh/talensi-chinese-mining-firm-shaanxi-ghana-suspended/

The article mentions an employee of Shaanxi Mining, one Elizabeth Yinnama and another employee, Shaanxi mining company’s Underground Mine Manager, Thomas Tii Yenzanya. These names don’t sound Chinese to me. This linked article also happens to be one of the few used by Patrick Bond that don’t support his accusation of BRI company abuse. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Only that on its own merits, the article doesn’t support the claim it was linked to.

https://iol.co.za/mercury/business/2019-02-26-baic-sets-new-timelines-for-projected-sa-vehicle-plant/

This article mentions the Beijing Automotive International Corporation (BAIC) and their delay in bringing production online which in turn led to small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) vacating the premises due to non-payment, which supports Bond’s accusation of broken promises of job creation. This article also mentions a newly-appointed chief executive locally, Nemo Tian – which suggests to me that this is again not a Chinese national being appointed the CEO.

I’ve been a mostly a silent reader of NC for years and I’ve followed your insightful commentary and read your sharp critique of Chinese policy without questioning it too much until now. But this time, I’d like to respectfully ask for a source of your statement that “Chinese backed investments (in Africa) invariably involve almost entirely Chinese workforces” when a skimming of articles criticising BRI conduct seem to contradict it. I’m open to the possibility that the examples in the above articles are exceptions to the rule and that on balance, statistically speaking, your statement still proves to be mostly true. But I hope my scepticism is understandable.

Seems like a mixed bag, again taking into account the relative dearth of balanced analysis.

I found two sources that suggest Chinese utilization of the local population for labor is quite high and in some companies majority are African. But high level managerial positions are still mostly staffed by Chinese.

https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/the-closest-look-yet-at-chinese-economic-engagement-in-africa

The evolving perspectives on the Chinese labour regime in Africa:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0143831X211029382

Thank you so much for the links. Here at NC, I always learn something new.

So do we really need a non-aligned movement again?

That, and the eradication of “elites” … see upstater’s comment above:

> Much of deindustrialization has been facilitated by South African elites that have gotten their cut in the robbery.

To the China mercantilism problem, it would appear to me that sending “bag men” to deal with Chinese “business men” is also part of the problem. I recall articles here over the years recounting how diplomacy is dead, and this is yer another aspect. When leaders meet to hash out details of these things, where are the knowledge transfer clauses? China sends many students to US universities evert year – to much MAGA consternation – where are the African students studying in China to bring relevant knowledge back to the continent? China didn’t grow to supersede the US/West by resigning itself to a black-box producer role. China learned and reverse engineered and TBH spied a bit to leap knowledge gap and production hurdles.

I dunno … if there’s no pivot from this, we’re cooked by virtue of simply transitioning from one hegemon to another.

Maybe we’re back to “workers of the world unite” time.

There used to be a tradition of training “3rd worlders” in GDR or Hungary of Czechoslovakia.

I don´t know how much China was involved in this kind of across-border solidarity.

Would it be amaturish to wonder what Ben Norton would say to all this?

Or Norton rather in lieu of serious economists who have studied China vis à vis former colonies of the West/Africa for decades.

I just have to think how large China is and how many people there are and how much knowledge there is being produced we never learn about but which transform policies by their governments.

The USSR was a culture and knowledge producing behemoth with work done which to this day in the West has not been looked into properly not even to a fraction of it.

And then – I repeat it – there is this huuuuge language barrier.

I am amazed the oh-so-smart elite around here do not address this in any meaningful way. Sure you can cage in your own population and dumb them down by NOT propagating to learn and understand Russian, Chinese dialects and so on.

I mean, it even fails as far as Portuguese. Hardly anybody speaks it in Germany. Spanish is a bit better but you can see it in the complete lack of proper policies towards South America.

sigh…

> There used to be a tradition of training “3rd worlders” in GDR or Hungary of Czechoslovakia.

I don´t know how much China was involved in this kind of across-border solidarity.

Yes! There is a wonderful call out to this in the opening scene “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” where Control sends Jim Prideaux to Budapest.

As Prideaux walks to meet his (fake) contact, the scene includes a few African young people in the bustling crowd making their way to trains.

> Would it be amateurish to wonder what Ben Norton would say to all this?

I vaguely recalled a BN video where the question of “why does China allow billionaires to exist in their socialist society?” was answered … I can’t seem to find it today though. Perhaps I am mistaken or misremembering. When searching for it earlier via Google, I got an interesting AI Overview (Disclaimer):

So I guess China’s businessmen are free to play hardball so long as it’s not in China or SOE related … ? ::shrug:: … does seem kinda shitty TBH. But we’ll chalk that one up to AI. I’ll have to follow up with one of the videos linked (just noticed) … maybe it’s the one I was looking for.

> And then – I repeat it – there is this huuuuge language barrier.

Right! And HERE … is where AI can play a useful role IMO … in helping to bridge that language gap whether is via talking through each others smart phones or augmented reality (AR) … that something I can buy into.

Thanks for your responses!

Great, thank you!

Shamefully I don´t recall the African folks in the Budapest sequence. Although I have watched it many times..

I do remember the real location where it´s set and also that Mark Strong speaks shitty Hungarian ;-P

There seems to be a growing number of African students attending Chinese universities, and has been for some time (a lot of articles about it from 2018 or so on) and here’s a recent one about scholarships: https://iol.co.za/news/2025-08-06-south-african-students-awarded-scholarships-to-study-in-china/

Thank you!

Ooooh, you set me off googling and some results are illuminating:

Political Depression and China’s Foreign Student Programs, 1950–1966 (via madeinchinajournal.com)

A book written by one of the students from that era is titled “An African Student in China” (via goodreads.com)

What was the return on these 20th century educational investments? What will be the return of the more recent and ongoing ones in the 21st century?

There seems to be no transfer mechanism.

thanks here too!

I was surprised that the non-aligned movement still exists. But doesn’t seem like they actually do anything. Much like BRICS. Too busy squabbling amongst themselves.

Thanks for the extensive report. Of course the Chinese would probably say that when it comes to the economic exploitation of poorer countries they learned from the best. At least they aren’t selling opium or bombing trading partners into submission although they have warred against Vietnam and may end up doing so against Taiwan to ward off their rivals–the (former) “best.”

> At least they aren’t selling opium or bombing trading partners into submission although they have warred against Vietnam

Thank ${DEITY} for small mercies, but when you start with the low bar the West set, well … #Natch

I always found that Modern China and the US compliment each other quite well. I also never bought into the idea of China bringing about a new order or the “shared community” of mankind. Sounds similar to the US platitudes of standing for freedom and democracy and equality. End of the day all countries look out for themselves.

Although China may not be a militaristic imperial power (yet), mercantilism can be just as bad. Take the British in India for example. Compared to other empires, yes they were benign in the sense they’d didn’t wipe out entire peoples in an orgy of rape and violence (ex. Mongolians, Spanish Conquistadores, US expansion West, Imperial Japan). But their economic and trade policy slowly bled India dry and in turn led to excess deaths. Same in Africa.

Deng Xiaoping once said at the UN: “If one day China should change her color and turn into a superpower, if she too should play the tyrant in the world, and everywhere subject others to her bullying, aggression and exploitation, the people of the world should identify her as social-imperialism, expose it, oppose it and work together with the Chinese people to overthrow it.”

I wonder if his words will be prophetic.

> I wonder if his words will be prophetic.

Indeed.

I’d add to what PK says that this isn’t a new problem: I first heard complaints of this sort in Africa twenty years ago, and there was already dissastisfaction with the quality of Chinese construction projects. (I stayed in one hotel, only a few years old, that was Chinese-built and run, but which was already showing signs of decay. The locals told me it had been built with convict labour, which is a persistent rumour about such projects.) But more to the point, the Chinese are just behaving as you would expect any large commercial player who needs raw materials and sells finished products to operate, in a world where “free trade” has removed the protections of the post-war era. They put their priorities before those of others, as investors tend to do. And unlike the British and French in the past, or the Gulf States today, they don’t have the same range of political and strategic interests in the countries they invest in, so from their point of view short-termism can make sense.

The failure of Africa to industrialise, as was complacently predicted in the 1960s, is a long and depressing story, which actually had a surprisingly good beginning. But the idea of selling cash crops to finance industrial development was a casualty of the deregulation of raw material prices of the 1980s, leading to massive indebtedness. More important than that, however, was the coming to power of a post-independence generation of leaders who, rather like their equivalents in the West, realised that financialising things was much easier and more lucrative than making them. Attaching yourself to an income stream for the export of raw materials was much easier than building a factory, and the Chinese, not being stupid, have realised this.

A few off-the-cuff musings:

1) Question: Wouldn’t further beggaring of the Global South (by China or any other players) continue to make China dependent on the higher income per capita countries for all those exports and high growth numbers?

2) Just spitballin’ here but…During China’s post 90s rise, certain players from the West did a good deal of the dirty work keeping other competitors, espicially in Asia, from rising as fast

3) During a recent visit to Beijing, one senior European businessman says he was shocked by the reception he received at one of the ministries. Previously welcomed as a valued foreign investor, he said a senior figure at the ministry treated him like a diplomatic adversary and accused Europe of being an unreliable partner.

Others told him the Europeans should stop fixating on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and human rights. “We like Donald Trump,” another official told him. “Why? Because he doesn’t talk about Ukraine and human rights. We can make deals with him.”

– from Why China is doubling down on its export-led growth model -FT

https://archive.ph/WMYeb/

Can one really make deals with Donnie? Probably only if one has leverage. Otherwise Donnie would take you to the cleaners.

I have an electrician I hire often who spends 1/2 the year in Uganda and Half the year in Canada. We talk a lot about politics in Africa and more specifically Chinas role.

From his Ugandan perspective I will paraphrase “It’s kind of the the same. The Americans and the Europeans show up and offers a 25 year extraction deal on great terms for whatever commodity they’re after, pull everything out of the ground in 5 years, then demand reparations for the remaining 20 years that they can’t use it. At least the Chinese will pay for everything they take, build a road to it, then leave.”

China seems in no mood to detour from the well paved capitalist road. If they have any answers on how to avoid the looming barrier of world-wide debt deflation it has escaped me. Here is an interesting paper on the Social Structure of Capital Accumulation. It’s a bit dated, but it’s conclusions appear to remain perfectly valid. “A liberal (read neoliberal) SSA is likely to suffer from inadequate aggregate demand, overcapacity, “coercive investment,” and financial crises.” It’s the same with any metropole, their primary exports are debt and despair.

I will need to read the full Bond article, but his reliance on a book co-edited by Ho-Fung Hung suggests a weak foundation. The abundance of anecdata reminds me of a Frank Dikotter book (not good). “Belief clusters” is a good concept, and is even more important to apply to the China-bad consensus in the West, though you are right to apply it to the China-good minority on YouTube. Perhaps a better analogy is they both want to take a kidney, but the West will leave you in an ice-filled bathtub in an empty warehouse, and China will build a hospital and leave you in a bed with medical care. Or rather, that applies to the respective governments, whereas private firms are more similar regardless of nationality. But the serious, detailed analyses are victim of the academic publishing atrocity, and hard to access.

Economic transformation in Africa: What is the

role of Chinese firms?

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jid.3664

https://sci-hub.se/https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jid.3664

Politics by Default: China and the Global Governance of African Debt

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003422198-11/politics-default-china-global-governance-african-debt-nicolas-lippolis-harry-verhoeven

Thanks for those links. Agree that it is difficult to find serious, balanced analysis.

Thanks!

I think part of the problem for Africa is that industrializing in the 21st century is inherently much harder than it was in earlier periods, partly because of the high technological base required for competitive manufacturing, and also partly because China is a production-turbo-maxxing economic power, and that is who they have to compete with. China is a “line must go UP!” country sort of how Western states are with their love affair for infinite GDP growth, the difference being that China doesn’t buy into the fake GDP garbage that Western countries prioritize (bankers+insurance UBER ALLES), instead they are the production maxxers. Due to Chinese political economy, with it’s emphasis on expanding industrial output, along with a huge internal market that is utterly and ruthlessly competitive, they have created an economy that seemingly no one can compete with on price. I mean just take a look at China’s consumer price inflation rate, where for the last five years it has hovered between 0.1 and 1 percent. China is the place where consumer goods prices go to get hammered into the dirt, and then beat up and hammered again. If you’re a wannabe industrializing country, how T.F. do you compete with that?

If China was like the US, with massive trade deficits, African countries might at least have had a chance to sell manufactured goods to China, but the Chinese are about as allergic to trade deficits as Germany is. China having a real hegemon resemblance to the United States (minus the American love of bombing, criminality and genocide of course) would be for China to run a giant trade deficit that African nations could use to piggyback development off of, but there is no universe I can see where that happens.