By Richard Alford, a former economist at the New York Fed. Since then, he has worked in the financial industry as a trading floor economist and strategist on both the sell side and the buy side.

Both fiscal and monetary policymakers have said that they will begin to unwind the stimulative policy stances when the economy shows signs of embarking on a self-sustaining return to full employment and trend growth. However, the yield curve remains steep as the markets fear higher real interest rates emanating from growing fiscal deficits and higher inflation stemming from the low level of interest rates and the growth of the Fed balance sheet. A quick review of recent US economic history suggests that that policy exits will be revolving doors.

The arguments in the post are generally consistent with mainstream economic views regarding fiscal and monetary policies. There is of course disagreement about the size of the fiscal multiplier and hence disagreement about the scale of the contractionary impact implied by a move to fiscal balance or discipline. There is more of a consensus among mainstream economists on the appropriate approach to designing and implementing monetary policy. There are also a number of alternative schools of thought regarding monetary policy and its impact on the economy. However, adopting one of the non-standard approaches to evaluate monetary policy would only establish what is already obvious: mainstream and non-mainstream economists disagree. As a consequence, monetary policy stance will be explored in the framework of the mainstream formulation.

Since the mid-1990s, the US economy has been almost continuously reliant on fiscal and monetary stimulus to maintain satisfactory rates of growth and full employment.

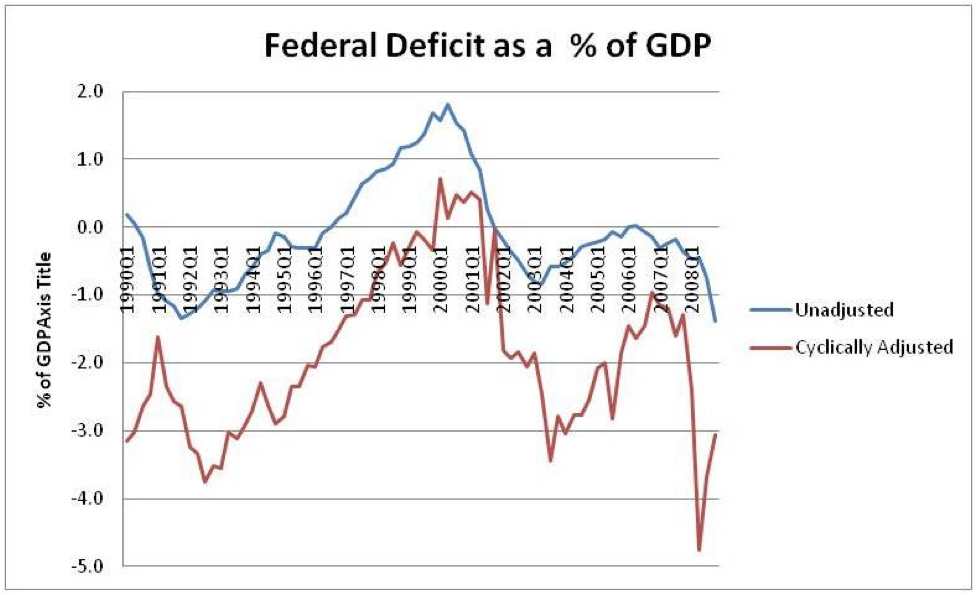

Simple measures of the fiscal deficit or surplus are not appropriate measures of the stimulus or drag provided by fiscal policy. Drops in revenues and increases in outlays occur automatically during a cyclical downturn and then reverse themselves during a cyclical upturn. Despite some limitations, cyclically adjusted budget measures separate out cyclical factors and are useful to determine, in a rough way whether the budget is providing a positive or negative influence on the growth of real income in the short run.

Based on CBO calculations, the cyclically adjusted Federal budget deficit (red line in the chart) was only in surplus for only 6 of the 76 quarters between the start of 1990 and the end of 2008. The cyclically adjusted budget was in deficit and providing stimulus in 70 quarters even though the economy was in recession for only 7 of the quarters between Q11990 and Q42008. The CBO has since reported that the unadjusted budget deficit for fiscal 2009 was 9.9% of GDP and the forecast (based on the President’s budget) for fiscal 2010 will be 10.3% of GDP. (Note: during the two periods in which the cyclically adjusted budget deficit was less than 3% coincided with asset price bubbles, which stimulated economic activity and capital gains based tax receipts.)

Given the jobless recovery of 2001 -2007, one must conclude that a move to fiscal discipline, other things unchanged, would contribute to rates of unemployment that have recently been deemed unacceptable. Consequently, any move to fiscal discipline is likely to be short-lived.

Many economists have argued that the Fed was “too loose for too long”, or overly stimulative post-2001. The Fed argues otherwise, pointing its adherence to the Taylor rule. However, there have been very public disagreements between advocates of different specifications of the Taylor rule. These disagreements have largely focused on the most appropriate measure of inflation. For example, John Taylor has argued the Fed policy was too easy from 2002-2005 based on a Taylor rule that employed current CPI instead of the forecasts of future PCE deflators.

More importantly, conventional Taylor rule analysis does not distinguish between domestic and imported inflation or between deviations of output from potential caused by a) declines in domestic animal spirits and b) increases in the world’s willingness to export to the US at unchanged or lower prices.

Consequently, given globalization and the inability of the Dollar to adjust to maintain external balance, the Taylor rule-based policy has been continuously stimulative since at least the mid-1990s.

The Taylor rule can be jury-rigged so as to reflect the US monetary policy stance that would have reflected only domestic factor-driven deviations from target levels of inflation and output.

Assume:

1. the traditional Taylor rule parameters ( 1.5x(the inflation gap) and 0.5x(the output gap),

2. Kohn’s estimate that imported deflation pulled measured US inflation (PCE deflator) down between 50 and 100 basis points per year for the period 1996-2006,

3. the excess of final purchases by US-based economic agents over potential US output, which grew from about 2% of GDP in 1996 to about 6% in 2006 (which implies “demand” averaged 2% (of GDP) higher than conventionally measured).

The amended Taylor rule suggests that the Fed funds target should have averaged more than 200bps higher (other things equal –although a difference of that size in the Fed fund target would have implied that virtually everything else would have changed.)

US monetary policy has been decidedly and consistently stimulative. Alternative statement of the conclusion: stimulative US monetary policy offset both the disinflationary effects of imported deflation on “measured” US inflation and the drag on net aggregate demand emanating from the net trade sector. It did so not by promoting adjustments to globalization, but by contributing the growth of unsustainable asset price bubbles which in turn supported bubbles in consumption and residential and commercial real estate investment. The anti-cyclical aggregate demand based policies pursued since the mid-1990s have not address the underlying structural problems.

The US economy is growing. Given the policy-based stimulus it would a shock if it wasn’t. The real question is: will it keep growing if the promised policy exits are realized.

Going forward, it is unlikely that exports will increase fast enough to compensate for any near-term exiting of the current very stimulative policy stances. The labor market, the trade deficit, the return of positive private savings, the excess supply of both housing and commercial real estate, the political pressures, and the crippled financial system and recent history suggest that any policy exit will short-lived.

The fact of this:

Simple measures of the fiscal deficit or surplus are not appropriate measures of the stimulus or drag provided by fiscal policy.

highlights the ideological terminology of this:

There is of course disagreement about the size of the fiscal multiplier and hence disagreement about the scale of the contractionary impact implied by a move to fiscal balance or discipline.

Even real Keynesians (let alone bastard ones) have ended up buying into this loaded language that cutting spending even where counterindicated equals “balance” or “discipline”, when actually in the English language as opposed to the Orwellian the measure of balance or discipline is to be balanced and disciplined according to the context.

The exact same action, like seeking to balance the budget, can be balanced or reckless, can be disciplined or chaotic, depending on the situation.

By now it’s clear that for “economists” today the measure of what’s “balanced” is whether or not something is expected to redound to the advantage of the rich or not.

And by now anything valued according to the deranged goal of getting the doomed exponential debt/growth machine going again is the essence of indiscipline, while any truly disciplined policy would be seeking to transform to a steady-state economy.

It’s all a joke by now. Even stimulus, which in theory could temporarily help during such a transition, will in practice be hijacked by kleptocracy.

That’s why we have to oppose every attempt of the system to prop itself up, no matter how reasonable a policy once seemed in the textbooks. A VAT, to give an example of something being touted in the MSM and among system wonks these days, could’ve been good as part of a general reform of taxation and spending priorities.

But under today’s circumstances it would only be used to render taxation more regressive, while the revenue was stolen by the elites. So no matter what was written about it before, today it would just be another kleptocratic assault.

Oppose everything this government tries to enact. You can count on it always being an intended robbery.

But under today’s circumstances it would only be used to render taxation more regressive, while the revenue was stolen by the elites. So no matter what was written about it before, today it would just be another kleptocratic assault.

Oppose everything this government tries to enact. You can count on it always being an intended robbery.

Not long ago I would’ve thought such comments to be radical. The more we learn of the Wall Street and political corruption, the more it seems logical. Why feed the parasites?

More different and useful insights. I can rarely find much to criticise in or add to Mr Alford’s posts, which is hopefully why there are few comments here.