I had the pleasure of finally meeting Steve Keen (he and his wife Melina are in New York) and it turns out he is adventuresome eater as well as thinker (he ordered maguro and natto even though I warned him, although I must say this restaurant’s version was actually gaijin friendly).

Steve told me about his presentation at a recent Minsky conference in Boston, and reader Don B had separately just e-mailed me about it. The entire talk is worth reading, and I thought I’d extract a few key parts.

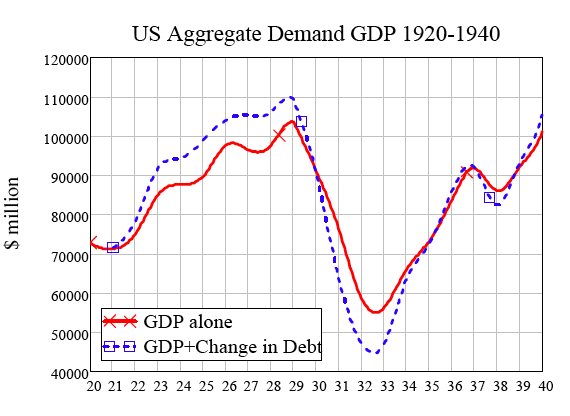

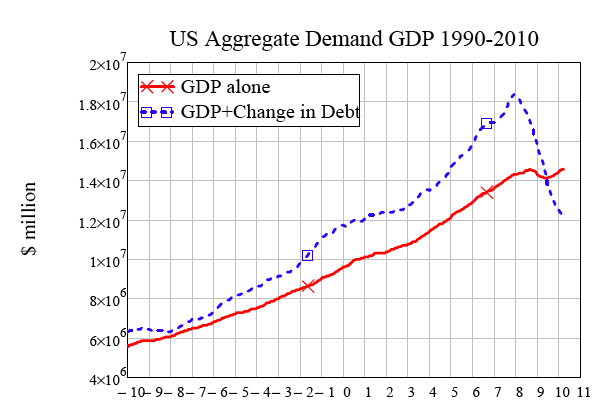

Keen, following Minsky, looks aggregate demand as GDP plus the change in private debt.

Growth in debt contributed to this definition of aggregate demand in the US to a greater degree in expansion period through 2008 than in the runup to the Great Depression:

His comments thus far:

Firstly, the contribution to demand from rising private debt was far greater during the recent boom than during the Roaring Twenties—accounting for over 22% of aggregate demand versus a mere 8.7% in 1928. Secondly, the fall-off in debt-financed demand since the date of Peak Debt has been far sharper now than in the 1930s: in the 2 1/2 years since it began, we have gone from a positive 22% contribution to negative 20%; the comparable figure in 1931 (the equivalent date back then) was minus 12%.5 Thirdly, the rate of decline in debt-financed demand shows no signs of abating: deleveraging appears unlikely to stabilize any time soon.

Finally, the addition of government debt to the picture emphasizes the crucial role that fiscal policy has played in attenuating the decline in private sector demand (reducing the net impact of changing debt to minus 8%), and the speed with which the Government reacted to this crisis, compared to the 1930s. But even with the Government’s contribution, we are still on a similar trajectory to the Great Depression.

What we haven’t yet experienced—at least in a sustained manner—is deflation. That, combined with the enormous fiscal stimulus, may explain why unemployment has stabilized to some degree now despite sustained private sector deleveraging, whereas it rose consistently in the 1930s….

Whether this success can continue is now a moot point: the most recent inflation data suggests that the success of “the logic of the printing press” may be short-lived. The stubborn failure of the “V-shaped recovery” to display itself also reiterates the message of Figure 7: there has not been a sustained recovery in economic growth and unemployment since 1970 without an increase in private debt relative to GDP. For that unlikely revival to occur today, the economy would need to take a productive turn for the better at a time that its debt burden is the greatest it has ever been..

Debt-financed growth is also highly unlikely, since the transference of the bubble from one asset class to another that has been the by-product of the Fed’s too-successful rescues in the past means that all private sectors are now debt-saturated: there is no-one in the private sector left to lend to.

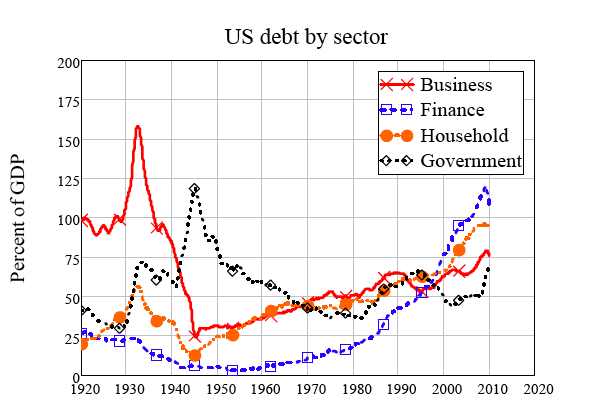

Yves here. Modern monetary theory types will point out that a government with a sovereign currency does not need to borrow to finance its activities, but you can eyeball Keen’s chart and see that private debt to GDP is higher even now than right before the onset of the Depression. Perilous little deleveraging has occurred.

The balance of Keen’s paper describes his Minsky model, which includes Ponzi finance (as in it simulates speculation on asset prices), which makes it unstable once certain debt levels are reached, just as Minsky predicted (and the breakdown level is similar to ones observed empirically).

There is intriguing material in there: comparisons, both in the model and empirically, contrasting a US response to the crisis (rescuing banks) versus Australia’s (shoring up households). And here is one finding:

The final debt-driven collapse, in which both wages and profitability plunge, gives the lie to the neoclassical perception that crises are caused by wages being too high, and the solution to the crisis is to reduce wages.

What their blinkered ignorance of the role of the finance sector obscures is that the essential class conflict in financial capitalism is not between workers and capitalists, but between financial and industrial capital. The rising level of debt directly leads to a falling worker share of GDP, while leaving industrial capital’s share unaffected until the final collapse drives it too into oblivion.

More bracing stuff from Keen here.

I agree with every contention cited here from Steve Keen’s remarks. (And given my cantankerous track record, I’m amazed that I find nothing to dispute, hey!)

But I will add an observation furthering those points, which his last chart here on ‘US debt by sector’ presents explicitly. Government and business debt have fluctuated widely through the 20th century for context-specific reasons. Household and financial system debt, by contrast, have moved in a fairly narrow band for that same duration—until 1990. From that point in time, household and financial system debt have both soared FAR above any norms for that duration. (And I expect for any norms of the 19th century as well, though I don’t have numbers in front of me on that.) And it shoudl be further noted that soaring household debt is simply a function of soaring financialy system debt since individuals were loaned that money _by the financial system_ which historically would have been much less ready to give households the dough.

The financial system went China Syndrome nutjob burn-through from the S & L crash, and the response to that of the public authorities. We can call this the ‘Full FED Ahead’ Era should we care to. It had two key rules: Give the financials all the credit they could possibly want and remove any and all rules they might conceivably not want. We are bolloxed by they inestimably cancerous blow-up of the financial system relative to all other parts of society over the last twenty years, at levels never seen historically in our society, that is the plain conclusion. And this did not happen by accident: we did it to ourselves. More accurately, our government leadership did it to the rest of us by completely advocating regulation and governance to the self-interested malefactors of great wealth, who went out and ate themselves to death. Or rather to TBTF Zombiehood, because though the financial system has died, it hasn’t gone away, but just sits on top of the credit system driving all of the oxygen out of the pond through its own rot.

We will have no recovery until we dismember and burn the zombies of the financial system: it is that simple. And we haven’t even begun, which is why there is no deleveraging to speak of. I won’t raise the issue of what happens with artificial government induced systemic debt goes sideways on us, the endless power to print more of it notwithstanding. But just look at the history of sector balances presented here, and the story writes itself. Too bad it won’t right itself; for that, we need justice.

I remember the S&L crisis and was so intrigued at that time I read several books about it and I became thoroughly disgusted. I knew then that something was very rotten and yet surprised there wasn’t more outrage, perhaps because a few people did go to prison.

And from a purely personal level, when I was in college in the early and mid 80’s, it was very rare to have a credit card. It wasn’t easy to qualify for one. (My parents, children of the depression, didn’t have one until the early 90’s and only after they were retired and travelled in the U.S. when it became a necessity to rent cars, etc.). The chart explains what we have known for a long time, that debt (credit cards, home equity loans, and so on) was used to make up for the lack of wage growth, and to finance a standard of living that only wages could not support.

Not to drone on, but I moved to Dallas in ’85 (the height of yuppy mania) after college (civil eng. degree) and of course had student loans to pay off. So I was starting off in a hole. This was just a few years after the previous recession. But the number of people (of average means) driving BMWs, Mercedes, etc., surprised me until a knowledgable friend explained that many people didn’t own, but leased them to maintain an image…a trend that only increased for the next 3 decades.

Keen did a great job here.

Richard, I agree with you except on one point. Placing the entire blame on the government. You see, there is an electorate that decides upon who will be placed in the gov’t.So therefore blame must also be placed on the electorate.

From my understanding, we have had the dumbest set of voters of all times in this country. On a broad level, people just got stupider over time. Religion plays a larger role in today’s politics than any form of intellect.And this trend is just growing with the Palin et al. We claim that we are a country of individualists yet the majority just wants a healthy pension as a reward for being lazy and habitually voting for idiots. We are raising kids without substance basically because parents have none to give to the kids. So when does this all end? There are countless brilliant people in this country yet their work is completely neglected because the populous simply cannot understand their work.

Talentless crud like Kim Kardashian or Lyndsey Lohan carry more intellectual weight than Daniel Dennett, Noam Chomsky or even Keen. And you want to blame your government for that?

I am seeing so many excellent comments this morning! And Zack’s is another good one. Out of curiousity I watched Carter’s malaise speech from 1978 on Youtube the other day. Regardless of how his presidency is judged, that speech was so accurate. From memory, “we have become a nation obsessed with consumption…” or something along those lines. But the public didn’t want to hear that shit.

More to your point, I don’t think increasing the voter turnout is always a good thing, especially the ‘low information’ voter.

But what none of you are acknowledging is that that the mainstream media were in on the con in 2008. How are “voters” supposed to make informed decisions with a politically corrupted media. Of all my highly educated friends, I was the only one who knew that American Progressivism is first cousin to European Fascism ( Though both are essentially politically Statist and economically socialist, Europe’s version has an important culturally-based nationalism not found in its American manifestation). And I was aware of this only because I’m retired, allowing me huge amounts of time to do independent research, plus I was involved with the “anti-war” movement in the US in the late ’60’s (and saw these “progressives” up close and personal.

“Regardless of how his presidency is judged, that speech was so accurate”

-funny, my son and I watch a clip of the same speech and reached the same conclusion.

No wonder this guy couldn’t make it past 1980. The speech was unbelievably accurate and just as unbelievably naive.

“There are countless brilliant people in this country yet their work is completely neglected because the populous simply cannot understand their work.”

There it is again. I just can’t understand it.

Excepting nobody I’ve ever voted for has been elected.

Therefore, “regulatory capture” trumps all.

Check out John Taylor Gatto’s work. Bismarck first hatched the plan to make the farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers of the 19th century more malleable and amenable to factory work. The US picked it up and continued it to this day.

Do you have kids in public school? I would argue that the most reliable lessons they learn are consumerism and the social pecking order rather than anything we’d call knowledge.

So, yes we got stupider, but it served the purposes of government. Reading common 19th-century writing (try The McGuffey’s Reader, or sample the Lincoln-Douglas debates) will bring tears when you consider how far we’ve fallen, and how much we’ll have to go through if we are ever to recover.

I’ve lived in England and the average person there is much better educated and informed, but their politics is only slightly less crazy than ours, and you can feel the deterioration. And they’ve been on a downward course for nearly a century now. What I’m saying is that this could happen to the US as well.

It’ll take a ‘white swan’ event to turn us around.

” . . . by competely abdicating governance [&etc.] . . .”

Wow– US debt by sector graph is incredible. Review and publish widely.

Richard- in this graph financial sector debt looks to have grown exponentially from 1950. Houshold and business debt seems almost linear– albeit with a blow up in Household shortly before the turn of the century (as you point out). Interestingly this coincides with financial debt overtaking household debt etc. but the fix (wrt. finance) seems to have been in long before…

When was Greenspan’s tenure again? Hmmm…

It’s best not to read a trend like that from a low, re. As a percentage of GDP, financal system debt was the same in 1920 and 1980, if in different conditions. Indeed, 1950 would be the outlier of the period: bad debts purged in the government forced do-over of the 30s; handsome profits funding the war in the 40s; tight government regulation so fewest stupid losses on the books of any time, consumers borrowing heavily for good cash flow. The activity as shown is bounded until, you guessed it, St. Alan the Greenspender sat at the controls and started pushing buttons to shunt money to his friends. *Grrrrrrrr*

The paper keeps referring to “capitalists”. Does anyone know who these people are? Or the “workers” either who keep being referred to?

“I guess you’re not a golfer…”

The most Concise Rebuttal always has been there’s monsters under the bed ha ha.

Capitalists = aggregate C hoarders

Workers = victims of C hoarders

Thats my take but you should ping Mr. Keen on his website start here:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit/

Capitalists are those who have been untaxed, who receive their ungodly wealth from debt-financed snake oil.

Workers are those who actually pay their taxes.

GE and ExxonMobil (and over 70% of American-based corporations, i.e., multinationals) = zero fed. taxes paid.

Maybe a simple test would be that the capitalist always goes by private jet, and thus is insulated from the humiliation-for-its-own-sake of air travel. Do you really think we’d have that nonsense if the super rich had to “spread ’em” and “empty your pockets”?

If you lose your job and can’t find another, is your lifestyle affected? If yes, you are a worker.

The obvious thing here is to suggest implementation of a Job Guarantee, not necessarily the printing presses.

Keen’s findings remind me, by the way, of an article by the late Wynne Godley, titled “Seven Unsustainable Processes” (http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/?docid=602). If you consider that MMT, I’m not sure MMT types would find much to disagree about in models by Keen.

I always love your Keene posts. I think it is now clear that Paulson et al were successful in their $2T expenditure of public funds of slowing the deleveraging. But it is obvious that deleveraging hasn’t been canceled. By 1930’s standards we have a long way to fall.

“If you consider that MMT, I’m not sure MMT types would find much to disagree about in models by Keen.”

Exactly right.

“gives the lie to the neoclassical perception that crises are caused by wages being too high, and the solution to the crisis is to reduce wages.”

A very important and potent rebuttal.

I suppose the orthodox view would be that supply and demand intersections determine price; labour needs to be demanded/not demanded by employers, and workers supply/not supply their labour. The balance of these two inputs determine wage, not policy.

However, as we all know, workers have to eat, live and raise families, so the above mechanical, ‘value free’ analysis cannot reflect the full picture. That wages have been kept so low for so long during high productivity and GDP growth is surely another blow to orthodox theory. In simple terms the data says clearly that the employer tends to have the power, especially when govt. is on the employer’s side. ‘Free’ market, anyone?

That said, I’m still sure technological unemployment has played a pivotal role in keeping wages low. There is less and less need for lots of labour to produce lots of stuff. For consumption to stay high while wages stay low, therefore, debt has to increase (aside from the fact that money is created as debt). It’s a no brainer, surely…

“I’m still sure technological unemployment has played a pivotal role in keeping wages low”

People have been saying that since the beginning of the industrial revolution, yet we’ve had periods since of nearly full employment and broadly shared prosperity.

Thanks, Alex, well said.

Alex,

That’s incorrect, rather remarkably so. The first TWO generations after the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the UK (where it arguably started) saw a huge risk in unemployment and large-scale migration of now unemployed rural laborers to cities (where they didn’t find much work either) due to two factors: displacement of textile work (done mainly by women at home as a cottage industry) by industrial looms and other forms of automation, often by workers in India to boot, and the loss of common pastureland, which often seized and turned over to sheep farming to support increased demand for textiles due to lower costs (this is crude but pretty accurate). Many households had some livestock, say a cow, that grazed on the commons; the loss of the associated calories/income was enough to push self-supporting households into poverty. You also saw limited pushback against the rise of other efforts by private mercantilists that worked to the disadvantage of British workers, such as the Corn Laws, but this was isolated.

This is WIDELY documented at the time; the downward mobility of many independent laborers, and the rise of grinding sweatshop work for those who could find replacement employment was the impetus for the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

You also have in the US, the so-called Long Depression (Krugman commented on it in passing in a recent column, http://dealbook.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/28/krugman-the-third-depression/) which lasted nearly all of the last final quarter of the nineteenth century, and the 1920s in England, a time of persistently high unemployment (this led Keynes to develop the thinking behind his General Theory, although he did not flesh it out till later).

Yves,

I said that since the beginning of the industrial revolution (meaning the entire 200+ years) we’ve had periods of nearly full employment and broadly shared prosperity, but I did _not_ say that there weren’t periods when that wasn’t so. Since there has been continual technological improvement, including ways of reducing the labor input required for a given output, you have to look at why we’ve had good times and bad. Since the labor requirement reductions have been continual, it says that the technological changes, while undoubtedly causing some displacement and grief, can have their drawbacks largely overcome by good policy.

Imagine how much better things would have been during the two generations you mention if there had been decent labor laws and labor unions. An absence of child labor, decent working conditions and reasonable wages would have made things a lot better. There was and is no reason why industrial work should be so awful. A classic example is the early days of the Lowell Mills, which while no worker’s paradise, were vastly better than the conditions in Britain and later on in the US. Charles Dickens was certainly impressed by his visit.

You also mention enclosure, which was government sanctioned theft, not an inevitable result of technological change. I don’t know how the common law was supposed to treat it, but any common sense definition of justice says that taking away people’s long standing right to use various resources, such as common pasture land, is just plain theft.

The Corn Laws did not work against the interests of British workers. The early free traders tried to convince the Chartists that this was the case, but the Chartists seemed to have read about Ricardo’s Iron Law of Wages (or deduced the same thing from common sense). Sure enough, while the repeal of the Corn Laws reduced food prices, industrial wages were reduced commensurately. The result was exactly as Ricardo had predicted – a transfer of income from old money (aristocrats and landed gentry whose income came from agricultural land rents) to new money (industrialists and financiers). To boot, agricultural employment was reduced as it was no longer profitable to cultivate marginal land.

The Long Depression was caused by financial mismanagement. While explanations of the causes vary, none of them point to an inherent problem of technological progress. The Long Depression was no more caused by technological change than the Great depression was.

There are numerous cases where chronic unemployment due to technological displacement was predicted, or at least feared in the popular imagination, but never materialized. For example, the adoption of early NC machine tools and greater factory automation in the 1950’s and 1960’s never lead to widespread economic pain, nor did the widespread adoption of mainframe computers the 1960’s (early mainframes eliminating vast amount amounts of clerical work) or PC’s in the 1990’s.

Alex,

You really need to read up on the early industrial era. I’m very familiar with that period, and you airbrush out a great deal of pain and distress. WE may be better off, but the result at the time would have been voted against roundly by the majority of people over the affected two generations. Wages to working people in real terms fell. You had serious downward mobility.

You can’t blithely say “better policy would have fixed this”. Really? Mass unemployment in a society with very little in the way of tax and social service provision? That’s just implausible.

And the seizing of the commons was perfectly legal and you know that. Its foundation was set most importantly by the peasant land reforms of 1660. This set the groundwork (no pun intended) for dislocation of those using common pastureland in the late 1700s and early 1800s:

The second wave of enclosures, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was therefore closely connected with the process of industrialization. Not counting enclosures before 1700, the Hammonds estimated total enclosures in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries at between a sixth and a fifth of the arable land in England.31 E. J. Hobsbawm and George Rudé, less conservatively, estimated enclosures between 1750 and 1850 alone as transforming “something like one quarter of the cultivated acreage from open field, common land, meadow or waste into private fields….”32 Dobb estimated it as high as a quarter or half of land in the fourteen counties most affected.33 Of 4000 Private Acts of Enclosure from the early eighteenth century through 1845, two-thirds involved “open fields belonging to cottagers,” and the other third involved common woodland and heath.34

http://www.mutualist.org/id61.html

You similarly blithely say in passing, ” To boot, agricultural employment was reduced as it was no longer profitable to cultivate marginal land.” Yes, and how much distress was associated with THAT change? Profitable for rentiers who expect income over what they have to pay farm labor (and transport costs, let us not forget) is higher than for people working the land for their own sustenance.

The romanticization of “progress” is one of the hallmarks of the modern era. You also omit some of the offsets. Just to name a few, the rise in mental illness in the US, which I would attribute directly to the weakening of community and family bonds demanded by the labor mobility required by modern commerce. I also suspect that future societies will regard our use of plastics, which are now poisoning water around the globe (even ocean water now has high levels of dissolved plastic in it) as vastly worse than the toxic effects of the use of lead by Romans (the old culprit was thought to be its use in plumbing; more recent research suggests its use in serving dishes was more widespread and dangerous from a health perspective).

Progress is not linear, and even when it eventually results in gains, it typically crushes a lot of people at the bottom of the food chain under its wheels.

Yves: “you airbrush out a great deal of pain and distress”

Are you reacting to where I wrote “technological changes, while undoubtedly causing some displacement and grief”? Because if you look at in context you’ll see what that means is that even with good policy there is some displacement and grief. I didn’t minimize the problems where there’s bad policy.

‘You can’t blithely say “better policy would have fixed this”. Really? Mass unemployment in a society with very little in the way of tax and social service provision? That’s just implausible.’

Given the social and political structures of Britain at that time it’s more absurd than implausible. But you miss my point, which is that good policy _can_ ameliorate the pain of technological displacement. The problems of late 18th and 19th century Britain were fundamentally caused by the unjust structures of that society, not by the industrial revolution.

I would hope that good policy is at least plausible in 21st century America. Therefore technological displacement doesn’t _need_ to cause major pain.

‘And the seizing of the commons was perfectly legal and you know that.’

I said it was unjust, not that it was illegal. Big difference. At one point slavery was legal too. I stand by my statement that by any common sense definition of justice, it was theft.

Furthermore enclosure was a process that started in the 13th century, so while the industrial revolution provided additional motivation for it in the 18th and 19th centuries, the industrial revolution didn’t start it and wasn’t the only motive. AFAIK at various times and places it was of questionable legality under the common law, and was at least sometimes opposed by the crown (Tudors). That didn’t stop later unabashed legalization of the theft by Acts of Parliament.

Alex,

I am well aware of the progress of enclosure in England, and separately, the link I provided also recounts its history. The impetus for the wave that took place around the Industrial Revolution was clearly competing uses for the commons made attractive by emergent tech.

Yves: ‘You similarly blithely say in passing, ”To boot, agricultural employment was reduced as it was no longer profitable to cultivate marginal land.” Yes, and how much distress was associated with THAT change?’

My point was that it _did_ cause pain, which was part of my rebuttal to your claim that repeal of the Corn Laws benefited British workers.

‘The romanticization of “progress” is one of the hallmarks of the modern era.’

And demonization of technology is another hallmark of the modern era. People romanticize a simpler bucolic era of sustenance farming, but nobody wants to put in 12 hour days of backbreaking labor for what today would be considered abject poverty. Of course there are tradeoffs, but I’ve yet to meet a halfway realistic person who’d actually prefer living before the industrial revolution.

If you want to romanticize something, go back to the hunter-gatherer era. Why break your back farming when you can get a better diet with a few hours of work per day? And you can avoid all sorts of nasty diseases by not having close contact with domesticated animals or clustering large numbers of people in towns. The invention of agriculture was a mistake.

“I also suspect that future societies will regard our use of plastics …”

Forget plastics, with enough GHG’s we may make half the planet unliveable. And we may wipe ourselves out in a thermonuclear war fighting over what remains. Yet so few want to go back to sustenance farming …

“Progress is not linear, and even when it eventually results in gains, it typically crushes a lot of people at the bottom of the food chain under its wheels.”

Because we as a society choose to let it do so.

A lack of progress can also kill us. How many more of our hunter-gatherer ancestors would have had to die if they hadn’t invented agriculture to accommodate growing population and climate change?

Does any commenter here know when/where the largest labor migration in the US took place?

It happened right after WW2 when the cotton picking machine was perfected and put to work in the fields of the Southern/South Western US. Black and white field hands and share croppers were suddenly unnecessary so they fled to the North, especially to Detroit and auto related jobs, in enormous numbers, and to a lesser extent to other Northern Cities.

The South to North migration of labor was much larger than the migration of labor to the West Coast of the US, caused in part by the dust bowl…but the N/S migration is little known to most…Perhaps because John Steinbeck did not write ‘The Cotton of Wrath’?

I cannot reccomend Howard Zinn’s history of the US enough. It contains not only US History but also the economics that drove the history…something most history texts do not attempt…Zinn’s History is by far the biggest selling US History book of all time and still sells very well.

This had a huge impact on the state of Oklahoma. Oklahoma was open to white settlement late, during the height of prairie populism. It was settle mostly by poor homesteaders but most of the land in the state could not support a family on 160 acres so the farmers went to cash crops, mostly cotton. At that time, the most cotton acreage a family could farm was about 40 acres so the 160 acre homesteads were broken up into 4 40 acres parcels, one farmed by the original settlers and the other 3 by share croppers. In Oklahoma, most of the share croppers were white. This set up a class structure where the poor homesteaders were now the rich family as they collected rent.

640 acre sections, each with 4 – 160 acre homestead. Each homestead further subdivided into 4 cotton farms. 16 family’s per square mile. By law, in the state constitution no less, each railroad was required to have a siding every 15 miles so every 15 miles along the railroads was a small farming community.

With automation, first the share croppers went, then the homesteaders who did not buy extra land found they could not compete with bigger farms. It is true that the banking crisis during the depression forced lots of Okies who borrowed against their crops off their land but a big exodus also occurred post-WWII.

And they always went West, after the war on Route 66 to LA, South Cal. In the US, as long as you head West, you are never a failure, you are always chasing another dream. Only if you head back East are you considered a loser, a quitter.

Alex, you misinterpreted my specific point about a 3 decade time frame to make a general (in your eyes contradictory) point about the fitfulness of ‘progress’ per se. Your interesting discussion with Yves aside, technological unemployment happens, as you accept, and though over time there does indeed seem to have been an ability to redress the unemployment pain, and return to full employment (though it is important to point out that ‘full’ means 5%+ unemployment today, compared to ~2% a few decades ago), there is a noticeable and increasing ability to automate more and more of what humans do economically. The pattern has of course been agriculture to industry to services. As services themselves become affected, we must ponder what sector might emerge to take up the slack. That, or consider radical alterantives to the current way of doing business.

My take is that humanity needs to embrace the fact that labour is less and less a necessary part of providing itself with the means of survival. It is also less and less of an effective money-distribution process. We need to rethink work, money, economics and much else besides.

And 200 hundred years is not all that long. The automation process has not run its course, not by a long shot. We should be embracing our technological prowess as an opportunity to rework how we live, alongside transitioning away from blind consumption and perpetual GDP growth as drivers of ‘progress’.

Toby: “you misinterpreted my specific point about a 3 decade time frame”

Where did you mention 3 decades?

“Your interesting discussion with Yves aside”

We did get a little off track, but it’s so much fun to debate with Yves that I find it hard to resist.

“We need to rethink work, money, economics and much else besides. And 200 hundred years is not all that long. The automation process has not run its course, not by a long shot.”

You’re talking about the broad sweep of history, and I’m talking more immediate concerns. If I were to refocus on the broad sweep, I would agree with, or at least seriously consider, some of your concerns.

I was only responding to the one line I originally quoted. My response may have been a little strong considering your overall post, but the demonization of technology as a job killer is sometimes trotted out as a universal answer to unemployment problems. Given that you think that some sort of economic restructuring is needed in response to technological advancement, it seems we actually agree. While technology can be a job killer, considering the benefits of technology, the proper response is a societal one to unemployment and wealth/income distribution issues.

However I’m not convinced that we need any radical restructuring in the short/medium term. Technological displacement has been occurring continually since the start of the industrial revolution (and even before). There have been times, for example the “Great Compression” of the 1950’s and 1960’s, when we did have low unemployment and good wages (broadly shared prosperity). Given that in the 1950’s and 1960’s we had technology far more advanced than during the Great Depression or the Long Depression, how is it that we were able to achieve this without radical restructuring? The Great Depression reforms were great, but hardly a radical restructuring. What evidence is there that we’ve now hit some sort of inflection point where radical restructuring is required? The simplest and least radical approach is to remember the lessons of the Great Depression and forget the idiotic “markets regulate themselves” 19th century dogma that’s been resurgent in recent decades.

My bad on the three decades. I was referring in my post to the period of stagnant wages of the last three or so decades and wrongly had the impression it was implicit. Sorry about that.

I’m not demonizing technology at all. My beef is with the ideology of perpetual growth and debt-based money, and the deeper underlying philosophies and assumptions that have given rise to the dangerous beliefs in perpetual growth and debt-based money as somehow sustainable and ‘natural’. Only radical solutions that get right down to the roots of where we’re at and how we got here are going to be of any lasting help. New thinking is cropping up all over the place and is very exciting, only the stodgy orthodox economics chaps don’t want to join the party.

To my mind we are in crisis (or crises) right now that demand bold thinking right now. The restructuring I wish for is not going to happen though, whether short or medium term, regardless of the pressing nature of the situation, simply because there is not enough collective will to deal with the situation realistically. Cultural momentum will throw us over the edge I fear.

“Given that in the 1950’s and 1960’s we had technology far more advanced than during the Great Depression or the Long Depression, how is it that we were able to achieve this without radical restructuring?”

A radical restructuring took place during the second world war (in terms of industry), and in some ways in the build up to it (I’m thinking of the New Deal), which laid the foundations for the ‘good times’ of the 50s and 60s. Also, there began then the transition to services which is currently running out of steam as technology displaces human workers even here. Tech could not do that during the 50s and 60s. Also, the ups and downs, while the consequence of a multitude of factors, are part of a broader trend we can measure in centuries rather than one or two decades strung together. This process is not finished by any stretch of the imagination, and while one might argue we are not yet faced with a pressing situation, I believe we are, because change takes a long time, and ecosystems, civilization, paradigms etc. are highly complex. Getting it ‘right’ will take a lot of thought, discussion, trial and error etc. Best get started in my view.

There is of course an almost endless amount to be said on this, but domestic duties are calling me away.

Toby: “A radical restructuring took place during the second world war (in terms of industry), and in some ways in the build up to it (I’m thinking of the New Deal), which laid the foundations for the ‘good times’ of the 50s and 60s.”

The problem with words like “radical”, which we both used, is that they’re so imprecise. This specific example, which you cite as radical, I cited as non-radical.

Duties call here too. Unfortunately one can’t hash out these things without even more time to devote to specifics.

Again, my bad on ‘radical’. Rereading my hastilly written post I see I used it twice with quite different meanings. The first usage is probably justified, but when I used it the second time I should have put it in single quotes. What I meant was ‘considerable’ or ‘deep’, rather than ‘radical’.

That said, I get the impression this is something of a non-discussion; that we probably agree. Were we face to face chatting this through over a beer, it wouldn’t be so awkward and halting. Ah, the Internet!

I agree with your observations about ‘prosperity’ alongside, and indeed even because of technological change and labour displacement, but do not believe these periods of ‘sunny economic weather’ gainsay the general and long term challenge technological change presents the current labour-for-wage model going forward. Until there is a viable sector to replace services, not to mention a money-system that encourages sharing, abundance and sustainability, I will continue to expect worsening conditions towards collapse, with technology, harnessed unwisely by a profoundly unwise paradigm, contintuing to do damage societally and ecologically, as a pivotal, though not exclusive, part of this extremely long term (millennia) trend.

Also:

“People have been saying that since the beginning of the industrial revolution, yet we’ve had periods since of nearly full employment and broadly shared prosperity.”

My point was about low wages as a consequence of the threat of displacement, and not about full employment. Labour is forced to compete with technology (amongst other things) globally, so must be prepared to exchange its work for lower a lower wages. Full employment is not precluded by this process, though it is becoming increasingly difficult to attain (see my point about that above).

Toby: “My point was about low wages as a consequence of the threat of displacement, and not about full employment.”

I understand, which is why I wrote nearly “full employment and broadly shared prosperity.”

Accepted.

The problem with that statement is that if you go the inflation rout you are reducing the wages for all industries. All workers will therefore, independent on the state of their employer, have to reduce their spending.

As I see it the only way out of this is actually to reduce the debt by paying some of it and wipeout the rest. However a main problem is how to compensate those workers with no debt and small savings that might be erased. If we don’t, the message is clear; don’t save, and if you want to save do not use our banking system. I think both would spell disaster for the economy, and I don’t even like our banks.

Public sector employment [in the UK] decreased by 7,000 (seasonally adjusted) in the first quarter of 2010 to 6.090 million.

Are these 6 million people “workers”?

“”Yves here. Modern monetary theory types will point out that a government with a sovereign currency does not need to borrow to finance its activities, but……”

uummmmm… the disconnect that I am not seeing addressed in this discussion is the truism that a sovereign national monetary system is capable of creating all the circulating medium without any borrowing – that none of the national circulating medium must come into existence as a debt.

Yet the MMTers are limited to showing that the government’s role, in its sectoral analysis approach, can be ‘financed’ by debt-free money – and that is only if we would remove the self-imposed constraint of something called the private, debt-money system of fractional-reserve banking.

Truth being that under a Constitutional government-issue, debt-free money system, as proposed by the American Monetary Institute, and also by MOST practicing economists some 70 years ago, we are capable of providing into the national economy ALL of the circulating medium required to meet our national goals of economic stability and full-employment. And doing so without creating any debts at time of issue.

After which, of course, it would be lent out to its highest and best use.

It’s the debt-money system that’s insolvent.

What we need is a new money system.

P.S. Happy Monetary Independence Day, America !

Agreed joebhed.

Indeed, we need a new economics, and much else besides. No one change is enough, and even seeing economics as an isolated discipline from physics or biology or ecology or whatever is part of the problem. Compartmentalization is part of the problem. Hence I recommend Charles Eisenstein whenever I get the slightest opportunity, so am doing so again here. I’m reading his book “The Ascent of Humanity” at the moment, recommend it highly. For those like me, interested in a comprehensivist analysis of where we are, how we got here and where we’re headed, he’s the guy.

Here’s part one of a seven part interview on youtube which gives a good foretaste of what he’s about:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEe3sZJg5kQ&feature=related

“Truth being that under a Constitutional government-issue, debt-free money system, as proposed by the American Monetary Institute, and also by MOST practicing economists some 70 years ago …”

Any links on the history of that?

“The Chicago Plan & New Deal Banking Reform”…Ronnie J. Phillips…foreward by h. p. minsky

We just posted a video on the Graham-Fisher-Douglas paper titled “A Program for Monetary Reform at economicstability.org .

We provide a link to the document there.

http://www.economicstability.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/A-Program-for-Monetary-Reform-1.pdf

This is a scanned PDF, but we will be posting a WORD version later today.

For the 70 percent consent figure, read the Foreword of the document, and once you do, you are likely to read the entire piece.

The purpose of the writing of this document is only more relevant today, since the debt-based money system is EXACTLY what has brought us to the servitude of our financialized debt-industry. And the solutions offered back then are the only real route back towards economic democracy.

Like I said, we hope to post a DOC and live PDF version later today or tomorrow.

Thanks.

Dear Joebhed,

Someone requested links. Here is the latest developing American Monetary Act. Critiques welcome.

http://www.monetary.org/amacolorpamphlet.pdf

And here is a brief essay on the Chicago Plan, with an interesting and short criticism of Keynes embedded.

http://www.monetary.org/chicagoplan.html

Sincerely,

Stephen Zarlenga, AMI

Wonderful paper from Steve Keen. I can only sit and applaud.

‘The addition of government debt to the picture emphasizes the crucial role that fiscal policy has played in attenuating the decline in private sector demand (reducing the net impact of changing debt to minus 8%).’

I’m not sure why the aggregate demand chart concentrates only on the change in private debt. Although there may be some difference in efficiency, rising government debt adds to aggregate demand too, as the quoted statement notes.

Deflationists tend to be dogmatic in claiming that inflation can’t happen without private-sector lending expansion. But there are counterexamples: does anyone claim that private sector debt was expanding (in real terms) during Zimbabwe’s recent hyperinflation? Pure printing-press inflation does not require ANY private sector debt.

Unless I’m badly mistaken, my buddy Weimar Ben Bernanke is preparing a pre-emptive, shock ‘n awe ‘QE II’ even as we speak. An apocalyptic showdown looms, in which the deflationists (I believe) will be vanquished by a remorseless wall of fiat currency.

GO, BENNY, GO!

Bill Mitchell, Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 shows why Zimbabwe is an irrelevant example. Weimar is even more remote. The conditions surrounding these hyperinflationary circumstances are unrelated to conditions prevailing now. Comparison is unjustified.

Nothing in the Mitchell article (which itself is vague about fiscal/monetary distinctions) addresses why change in government debt should be excluded from Steve Keen’s first-pass aggregate demand analysis.

Focusing on the currently depressed state of private debt expansion leads to a direr conclusion than I believe is justified. Government deficits have expanded to offset private sector saving.

Meanwhile, the monetary authorities can monetize debt (or not), whether total debt is expanding or contracting. Two to five years out, their open market operations will have more effect on inflation (or deflation) than the fiscal stance.

What is amazing is how little the economic “science” knows for sure, there are competing alternatives on most things. They don’t even have a serious comprehensive knowledge about how money works. There are consensus agreements among established “scientists” on several things but no true knowledge. Despite this they repeatedly serve what their masters want to here. Could this be the core problem of this “scientific” branch, that they primarily are not scientist but their masters servants?

“They intimidate people“

Money is really an expression of spirit and imagination. Since Locke said that people are entitled to Life, Liberty and Property and since Money = Property as Particle = Wave, then there is a natural law that says people are entitled to money, which is as much to say they are entitled to their own spirit or soul. Jefferson extended Locke with his permutation of Property to Pursuit of Happiness, which is the same as search for one’s soul. This can be a painful process, as the failures and bankruptcies in the private sector attest, which have as their metaphorical equivalent the failures and bankruptcies in one’s search for their own highest self. These are all energetic metaphorical relationships that are clear to students of Contemporary Analysis.

As a result, the anthropologists and mythologists such as Frazer; the pyschoanalytical writers such as Jung and Freud; and the group pyschology theorists (there are few, such as Gustav Lebon and Freud again and Charles McKay to a point, although he was more a journalist), as well as writers on the structure of consciousness, are really a foundation for the serious study of money, in my view.

I doubt there is a single economics department in the nation that includes this in the cirriculum. It would overhwelm the discipline, which seems mostly concerned with the anatomy of an economics system and not the deus in the machine. This is similar to the study of medicine, where the anatomical and pharmacological approach is balanced with pyschoanalysis and psychotherapy. In shamanic societies, the shaman administers to both, with some sucess, although with failures that western science can address.

sorry: money = property as wave = particle, what I stated above is reversed. I always reverse those because I type too fast and I’m careless with my braindumping.

another error I made was to implicitly equate economics and medicine. what I meant to say was that medicine is more advanced because it acknowledges the god in the machine. I really need to slow down. boowahahah ahahahahah! I get too excited.

Intriguing work!

Which leads to the question, what’s the point of having debt in the system at all? It seems to do nothing except to exaggerate natural economic swings.

Ponzi good times need to be paid, eventually, painfully.

Cindy, debt is like dynamite. It is indispensable in heavy construction and safe in the hands of experts that respect its power. But it is very dangerous in the hands of the careless or fools, and it can be used destructively by people selfishly bent on their own advantage, like criminals blowing up bank vaults. Same with debt.

“like criminals blowing up bank vaults”

What’s your concern, that criminals blowing up bank vaults will steal from the criminals who own the bank vaults?

Otherwise a good analogy. Some debt is extremely useful – too much is extremely dangerous.

Other side of debt is credit. A primary purpose of banking is prudent credit extension. A lot of the problem now is the result of imprudent lending and outright predation. In a just system, those lenders would have to take the consequences instead of being backed by a government they bought.

“In a just system, those lenders would have to take the consequences instead of being backed by a government they bought.”

You’re clearly not a libertarian, since you clearly don’t believe in property rights. Since they bought the government, they get to enjoy the fruits of that ownership.

Alex, I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Ok, let me try:

They paid for the government fair and square, so now it’s theirs to enjoy, with it’s money printing-presses, revenue streams and in-house armies and spy-agencies. It was on sale for an excellent price too.

C.

There needs to be a clear distinction made between real debt – like when you HAVE five dollars and you lend it to me and I use it and then pay it back and you have it again – and money being created as a debt – where the banker does NOT have the five-dollars, and creates it via PN/security agreement, and “bank-credit-deposits” it into my account and I use it and then pay it back and the banker destroys the money.

One of those is a perfectly legitimate commercial act, the other is a thievery based tax on all of the citizens of this country, perpetrated on EVERY dollar that comes into existence, CAUSING the booms and busts of modern economies.

We need debts to move real money to where it is needed.

We do NOT need debt-based money creation by private bankers, the biggest fraud ever perpetrated on mankind.

End fractional-reserve banking and debt-money.

Let banks get back to banking.

Thanks for the Keen paper.

Very interesting analysis and point of view.

Deflation is at work throughout our economy. Take rent for example; major deflation in prices. Take many goods; prices are being cut.

However, I believe the key element holding back significant deflation is THE PRICE OF OIL. Have you noticed how stubbornly it holds up? Anyone suspect collusion with key Arab players? Oil is a primary price input for a vast majority of our economy. If it drops, prices will plummet. I believe, the US Government and others are attempting to hold the price up through output regulation; primarily by the Saudis.

Thanks for the excellent post.

Back of the napkin, in the Great Depression, the US GDP did not begin to recover until combined private debt decended to about 40% of GDP. That would be 25% Household, 12% Business and 3% Finance. This is a very scary number indeed since it implies the current private US debt levels could plummet much further before a point of sustainable recovery is reached.

Yves,

I’m puzzled by your MMT comment there. I fail to see anything in Keen’s analysis inconsistent with MMT. It makes perfect sense to me that the policy response in the current crisis has reduced private deleveraging compared to the 1930s. This is precisely why MMT’ers advocate, in ADDITION to a strong policy response, substantial reform of the financial sector (there’s literally dozens of research publications and blogs on this topic by MMT’ers in the past few years). Steve (and most of his “followers”) repeatedly fails to recognize this part of MMT, even though I and others have reminded him many times (several MMT’ers were either colleagues or students of Minsky, in fact).

It’s the inclusion of government debt on the debt to GDP chart. It puts government debt on the same footing as private sector debt (the other types of debt on the chart). Note his later model has only households, capitalists, and bankers.

“It’s the inclusion of government debt on the debt to GDP chart. It puts government debt on the same footing as private sector debt (the other types of debt on the chart).”

Eric Tymoigne, an MMT’er, did the exact same thing here, albeit more than a year ago so the data Keen shows since the recession was largely unavailable (this was a short piece that he took from a longer paper on financial instability):

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2009/06/how-big-is-debt-problem.html

So, as I said, no inconsistency with MMT. We’ve even done the same thing ourselves.

OK, now I understand. From an MMT perspective, it’s ok to put them all on the same graph as long as you understand the fundamental differences as you’ve noted. Eric can certainly do that.

Family lore says that my grandfather, a union construction worker, bought his first car with cash after WW2. How many construction workers can do that now ? Of course, it is common to buy with cash in China. Point being, debt financing in US households has most definitely contributed to a feeling of false prosperity.

That is interesting. The casual acceptance of debt and your point about false prosperity is right on. That has been the foundation of the American Dream for the last 25-30 years.

Modern monetary theory types will point out that a government with a sovereign currency does not need to borrow to finance its activities, but you can eyeball Keen’s chart and see that private debt to GDP is higher even now than right before the onset of the Depression. Perilous little deleveraging has occurred.

All MMT’ers are in agreement with Minsky. Randy Wray was a student of Minsky, for example.

One of MMT’s main contentions is that if government does not make up for the public’s increasing desire to save/delever, then absent an offset by exports (unlikely for the US and mathematically impossible for all countries simultaneously) deflation will result.

This is the reason that MMT is so opposed to fiscal austerity to “solve” the current problem. It will greatly exacerbate it instead. The world is not past the threat of global depression by any means, and the best case scenario to be hoped for under current policies is Japanification and a lost decade or two. This applies not just to the US. European policymakers are even more deluded in their zeal for austerity.

And as others have observed a monetarily sovereign government that is the sole provider of a nonconvertible floating rate currency of issue is not financially required to issue bonds at all. The CB (Fed in US) can just pay a support rate on reserves if it still want to control the overnight rate (FFR), or it can set the overnight rate at zero, like the Bank of Canada does.

I don’t understand why deflation is such a boogeyman to be avoided at all costs. Ultimately the issue comes down to how we correct the imbalances between debtors and creditors, the 1%s and everyone else, however you want to put it. Even if you buy MMT at face value (which I do for the most part) that does not how the money will be used by the private sector, which right now is tied up both financially and operationally in a dead paradigm. I view most government spending at this point as a waste because it is acting as status reaffirming instead of encouraging people to focus on a new economic foundation.

To me allowing deflation of assets is the most politically feasible and “fair” way of correcting the imbalance, as well as getting people to move on. Of course this will cause mass unemployment which is why it would need to be accompanied by a mass government jobs program, but that is much more realistic to talk about at this point than tackling corporatism head on.

“I don’t understand why deflation is such a boogeyman to be avoided at all costs.”

Because of the debt-deflation spiral. If wages/prices fall then servicing existing debt becomes a greater burden for workers/companies, leading to further deflation. Eventually there are too many bankruptcies and the creditors loose out too.

Asset deflation is a bit different, and I think some of it (especially in real estate) is unavoidable. The cure for that may be worse than the disease, but it still won’t be pretty.

Deflation is a bogeyman because it is very difficult to reverse. It not only has economic consequences but social and political ones that can not only topple a regime but a form of government. It is extremely dangerous for a government to allow the nation’s economy to fall into this trap.

But just throwing money at the problem is not optimal, and it leads to further problems. Policy and practice led to this mess, and that needs to be addressed. The incentives are wrong. The government can create incentive/disincentives through a variety of means, from fiscal policy to regulation, oversight, and accountability.

For example, fiscal policy can direct funds through expenditure and remove them through taxation. Legislation and regulation are useless unless they bite.

Right now, the criminals that cause this mess are being rewarded.

I disagree. Deflation by its very nature will have a bifurcation point where the positive feedback loops become negative feedback. This occurs because of different elasticities in different asset classes. Basic materials, commodities and luxuries have steep price curves when compared to necessities. The former are also built on much higher leverage. At some point (admittedly a very low point from where we are right now) debt loads will stabilize relative to wages. Many people will get wiped out, but the bottom 70% of the country has no effective wealth anyway so the only threat to them is joblessness, something that can be addressed through government programs that will be able to have very cheap (transforming) infrastructure projects.

By contrast trying to service debt through increased monetary injection has no obvious negative feedback point and can spiral out of control very easily.

In theory I have nothing against changing incentives and having the government try to avoid deflation, but in practice it is completely captured. The majority of our fiscal deficit spending is going overseas through the trade deficit or to corporatist elements. One can talk about theoreticals all day, but in our present circumstances I see deflation as the best way to change things…which is ironic because the people in charge are the ones that are pushing deflationist policies without understanding how it will undermine them. So be it.

Of course what I am very concerned about is that there will be no counterbalance of strong leadership that will support people at their time of need. The sociopathy prevalent in our culture is insane and I do worry that deflationary policies ups the risk of social strife. In general I am becoming much more fatalist about a major crash because at the end of the day the pie is getting smaller and the people that are in charge don’t want to make sacrifices.

Right, if there isn’t a revolution first. The peasants armed with pitchforks and torches were turned back from Washington by the army during the Great Depression, and a coup d’état was engineered against FDR, but it was ratted out before it could be launched. Yes, it can happen here.

“All MMT’ers are in agreement with Minsky. Randy Wray was a student of Minsky, for example.”

Exactly my point at 10:57am above, too. I don’t see the point of Yves including that MMT statement, unless she’s repeating something Steve said to her–actually sounds like the sort of mis-characterizations of MMT he somehow manages to make regularly despite the number of times we’ve all corrected him.

As indicated earlier, the chart immediately above the remark has government debt to GDP along with various type of private debt. MMT sees government “debt” as having a very different role and impact than private sector debt.

” there has not been a sustained recovery in economic growth and unemployment since 1970 without an increase in private debt relative to GDP.”

The 70’s oil shock continues to rock the foundation of an economy based around cheap available oil. Road building was the industry of choice for the current administrations stimulus spending hoping that new paved roads would somehow

continue the urban build out with another round of shopping centers,schools, fire houses,warehouses and of course houses but its not happening a clear sign that the post war economic era has run out of cheap gas.

“class conflict in financial capitalism is not between workers and capitalists, but between financial

and industrial capital”

I do not agree with this. Certainly, we have seen Wall Street beat up Main Street, but the key remains 30 years of flat wages and an enormous maldistribution of wealth upward, creating the paper economy which established and expressed the dominance of Wall Street (the investment class) over Main Street (workers).

MIchael Hudson:

source

Prof. Hudson’s comments, ultra-brilliant as always!

I’ve been reading him for over thirty years, and for that time and longer he has always been on target.

You go with the correct thinkers, you don’t go with the sociopaths…..

Keen’s brand of circuitism and MMT are like ships passing in the night. They should be complementary. They just need to listen to each other – in both directions.

Did you not see my three posts here noting that the entire Keen analysis here was consistent with MMT? We are well of each other. The “problem” from the perspective of many MMT’ers is that Steve perpetuates a lot of misinterpretations of MMT, even as MMT’ers have repeatedly told him otherwise. And MMT’ers aren’t the only ones that have had that experience. You generally don’t see MMT’ers critique anything by Steve unprovoked; it’s almost always the other way around, where MMT’ers have to defend themselves against some misinterpretation by Steve. We certainly respect his analysis, though, particularly of the dynamics of horizontal money.

“The “problem” from the perspective of many MMT’ers is that Steve perpetuates a lot of misinterpretations of MMT”

Such as? I’m curious.

Here is one recent example–see the last three paragraphs of this link. It’s the final two paragraphs where he completely mis-characterizes MMT. The rest of the post was excellent. But he’s been making these same mistakes over and over regarding MMT (as well as others), and we’ve corrected him over and over, to no avail. At some point we just all stopped engaging.

http://www.businessspectator.com.au/bs.nsf/Article/federal-deficit-surplus-monetary-policy-pd20100604-644YA?OpenDocument

Also, I posted a rejoinder to that link, but it didn’t make the censors’ cut.

stf,

I don’t edit comments, nor does the software on this site (save when I block IP addresses of spammers and repeat violators of comments policy, and then after warning). People, including me, have occasional trouble with it.

I was referring to the link, not to Naked Capitalism. Never any such problems with the latter!

Yes, in that article Keen off-handedly criticizes Mosler’s deficit proposal and seems completely unaware of Mosler’s proposals for financial reform along the same lines that he is recommending.

Right, Tom. Except that he IS aware that Randy Wray was a student of Minsky, and that there’s probably 3 or more MMT’ers on top of anybody’s list of top 5 Minsky scholars in the world. All he has to do is go to the Levy site or the KC blog and look over what’s been published by MMT’ers over the past few years and it would be absolutely clear. He could just browse abstracts if he doesn’t want to read the entire papers. That’s the big difference between posting to the web and doing real scholarship–that sort of “oversight” could never make it through a decent editor or referee (though there are exceptions, for sure, but those get sorted out later by rejoinders and critiques by other scholars). But on the web, that sort of thing just perpetuates misunderstandings.

The reason for my comment was that putting government debt to GDP on the chart immediately preceding the remark is contrary to the MMT view of the role of the government sector (when it controls the currency) v. the private sector. That was the one place in Steve’s presentation where this was an issue. Note that his model later includes only bankers, capitalists, and workers.

I guess the definition of defensive is not realizing somebody is on your side.

Wasn’t implying that it was MMT that should be making the reciprocal effort here.

OK.

anon,

I agree with you.

There’s something seriously disturbing in disproportionately defensive reactions.

“Keen’s brand of circuitism and MMT are like ships passing in the night. They should be complementary.”

Keen is well aware of the possible connection between his work and MMT. He’s had at least one post about that on his blog. IIRC he basically said that he wasn’t quite ready to try marrying it to MMT yet, as he wanted to work on other aspects first.

Alex, Steve seems to be alone among the MMT’ers and circuitists about not recognizing this complementarity.

Don’t know if he is alone, but he should do more homework on MMT before judging its role in the amalgam.

yep.

“The reality is that finance takes the form of debt – and gambling. Its gains therefore were made from the economy at large. They were extractive, not productive. Wealth at the rentier top of the economic pyramid shrank the base below.”

Good point!

But, perfect for a global neofeudalist plan.

“gives the lie to the neoclassical perception that crises are caused by wages being too high, and the solution to the crisis is to reduce wages.”

Have you ever heard anyone say this? It has been argued in the UK that the problem with current policy is that it pays people not to work, but stay on welfare of various sorts, because they are better off that way. It has been argued that if you are in state housing, which you lose if you move, that you will not then move in search of work. Or even if guaranteed work in the new location.

But the idea that the current crisis is caused by or exacerbated by ‘too high’ wages? Never heard it said.

You need to do your homework. This IS the standard view of neoclassical economics, it is pervasive in the literature. Anything that is wrong in the economy can be corrected by price. If there is a downturn, it can be remedied by lowering prices and wages.

If there is a downturn, it can be remedied by lowering prices and wages.

That stickiness thing is a problem, as Keynes observed. No one has yet figured out how to make prices and wages elastic so that supply and demand fall into equilibrium. Nice theory, though.

This is a common misconstruction of what Keynes said, and I suspect it is the doing of “Keynesians” like Paul Samuelson who bastardized Keynes (they turned him into a special case of neoclassical economics, I discuss this at some length in ECONNED. They excised critical bits, like his view that the operation of the financial sector makes economies inherently unstable).

This is from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics:

Economists still argue about what Keynes thought caused high unemployment. Some think he attributed it to wages that take a long time to fall. But Keynes actually wanted wages not to fall, and in fact advocated in the General Theory that wages be kept stable. A general cut in wages, he argued, would decrease income, consumption, and aggregate demand. This would offset any benefits to output that the lower price of labor might have contributed.

Yves, I was alluding to Keynes’s criticism of the neolib micro model of supply/demand elasticity applied to macro. As I understand it, Keynes held that this model doesn’t work because of stickiness. But the neolib solution even today is cut wages, prices will fall into line, and markets will return to equilibrium. They see it as a supply-side/investment problem.

Post Keynesians disagree, saying that the problem is a demand-side/income problem and reducing incomes will just compound the deflationary trend, especially in a period of debt deflation, such as we are experiencing now with some many mortgage defaults, for instance.

Most neolib economists don’t focus on finance and don’t know too much about it, either.. Since they are the orthodoxy, we are stuck with bad policy. Circuitists (like Steve Keen) and MMT’ers are advancing counter-proposals based on monetary economics. To them, cutting incomes, and thereby the ability to service debt (without corresponding cram- downs) will lead to deflation, not equilibrium.

“As I understand it, Keynes held that this model doesn’t work because of stickiness.”

Tom, that’s the neoclassical interpretation of Keynes. Keynes was very clear in the GT that stickiness wasn’t the problem, and that even if you had flexible prices and wages it wouldn’t solve the problems (and could make them worse).

Ok, my bad.

Buy and read ECONNED for an interesting romp through the neoclassical detritus, among other things.

Great paper by Keen. One thing it clarifies is why the financial sector has grown so large in recent years. It is precisely because debt, in all its forms, has expanded so much. The financial sector feeds on debt as its raw material. Debt has to be sold, resold, rolled over, structured and restructured. Portfolios must be managed, spreads must be captured, and mismatched maturities must be brought together, etc, etc. The more debt, the more work (and pay) for financiers.

From a Minsky point of view, it is no surprise that the financial sector grew along with the debt until, on the eve of the crisis, it absorbed a substantial portion of all the profits in the system.

For the future then, whether we like it or not, a large financial system will be with us for as long as there is substantial debt to manage. So unless or until there is a collapse, there will be plenty of work to do for Goldman Sachs and all the others.

Yves,

Great to see you getting together with Steve Keen. The two of you have been some of my favorite sources of information on the Great Meltdown, from complimentary POV’s (business/politics perspective vs. economist’s perspective).

I’ve long found Steve’s debt/GDP graphs scary, and I’m glad you’re introducing them to more of your readers. He’s convinced me that serious private sector deleveraging is indeed necessary for a real recovery, and hence the Fed’s “hair of the dog that bit you” approach to our private sector debt hangover is misguided. Not to say the Fed should suddenly jack up interest rates, but ZIRP is perhaps going too far. So far its main effect is to enrich banks that profit off the interest rate spread.

It’s also an important reason why I think the bank rescues were misguided. Better to take insolvent institutions into receivership and let the bond holders take haircuts. That’s deleveraging.

Of course, by an astounding coincidence, both ZIRP and the bailouts have the banks as their main beneficiaries.

Question: do you or Steve Keen have any suggestions how private sector deleveraging could be accelerated? (preferably without causing a bigger meltdown in the process).

P.S. What’s so adventuresome about maguro? I thought it was just tuna.

etter to take insolvent institutions into receivership and let the bond holders take haircuts. That’s deleveraging.

Fat chance of that happening while financial capitalism rules. The first thing that is necessary for real change is getting the money out of politics and locking the revolving door. The second thing is busting TBTF down to size. TBTF = Too Big To Exist. The third thing is ending central bank independence, which is tantamount to letting a small group of unelected and unaccountable technocrats set the price of money. And so forth….

It isn’t the maguro, it’s the natto. Natto is one of those things Japanese often get unsuspecting Westerners to try because it’s usually very much an acquired taste and virtually all gaijin recoil. Natto is fermented soybeans. They are usually very slimy and have a very strong taste. This one happened to be very mild and was actually interesting.

Rob Parenteau the other day had a post that suggested the business sector was hoarding cash and looting through exorbitant executive pay (my rough recollection of what he said).

Just as government debt cannot be compared to household debt, neither can corporate debt. Corporate debt is offset on the balance sheet against “shareholders equity” which is created from stock sales and retained earnings. Households have nothing similar — “wealth” to a point, but that is all tied to market value and its vagaries.

Even though business debt, in the charts above, is rising. That does not imply what the ratio of debt to capitalization is, which is a more relevant financial measure of corporate leverage. Moreover, it would seem, visually speaking, that business debt could rise if more businesses were created globally as well as if business with strong balance sheets borrowed. I reall all the time about how strong many corporate balance sheets are.

It may be that corporate borrowing could act as a reservoir for private savings to a degree to juice the economy forward.

But corporations don’t now see — through failure of imagination or through lack of confidence in the larger economic system — the chance for profitable deployment of the capital raised through debt offerings, in a way that would also raise retained earnings.

We’re in an imagination lock right now. There are plenty of poor people who would like to work and prosper and buy things, but they and their potential employers are frozen in an imagination mind chain lock.

Viewing the great recession as arising because of to much debt misses the other side of the coin, the savings side. Borrowing has to equal savings. Consumer wealth inequality partly arising from tax cuts for which government had to replace with borrowing, the ability of the financial system to magnify savings, and trading partner mercantile policies contributed a savings side cause to the great recession. The following provides a simplified macroeconomic model of how wealth and income inequality might have increased and contributed to causing the great recession.

Macroeconomic analysis starts with four cohorts, consumers (C), businesses (B), government (G), and trading partners (F). To understand the following dynamic, consumers will be divided into two cohorts and businesses will be divided into two cohorts.

The two business cohorts are finance industry (Bf) and non-finance industry (Bn). Understanding the finance industry (Bf) cohort is critical to the following model. The finance industry (Bf) cohort is a conduit for matching savings and borrowing and a creator of an increasing level of funds for borrowing. Money is created by the Federal Reserve. Fractional banking magnifies the funds created. If bank reserve requirements are 10%, the fractional system provides an increase of $10 in loans for every $1 created by the Federal Reserve. The finance industry (Bf) cohort magnified Federal Reserve money creation even further by the creation of shadow banking units, some of which had reserves of about 3% creating $30+ dollars for every dollar of reserves.

For the consumer cohorts, assume a correlation between income level and savings. Stated simply assume low income consumers to be net borrowers and high income consumers to be net savers. Assume some percentage of consumers such as the lowest 90% in income borrow on net an amount equal to the net savings of the highest income 10%. Whether 90% is the right number is not critical to the following discussion. The consumers cohorts are consumer borrowers (C90%) and consumer savers (C10%).

Some observations about the 2000s leading up to the great recession. Government (G) net borrowing and trading partners (F) net savings in the US were about equal. The finance industry (Bf) accounted for more GDP and profit growth in the 2000s than non-finance industry (Bn). Consumer savings were low and are assumed to be zero for the following discussion. Consumer income and wealth inequality did increase.

Here is a simplified description of what took place.

* Government (G) lowered taxes benefiting primarily the consumer savers (C10%) cohort. This increased the level of savings searching for investment.

* Consumer borrowers (C90%) wanted to buy much of our trading partners (F) products and services.

* For consumer borrowers (C90%) to buy these products and services, savings had to be made available to them.

* As we well know now, the borrowing of consumer borrowers (C90%) greatly exceeded their ability to pay from current and expected income.

* Savings was made available to consumer borrowers (C90%) through the finance industry (Bf) based on expected increases in new and existing home values used as collateral.

* Trading partners (F) on net ran mercantile policies. The US trade deficit (and current account deficit) was financed by trading partners lending to us. In other words our trading partners on net had dollars they wanted to save instead of spend.