By Delusional Economics, who is horrified at the state of economic commentary in Australia and is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness.

Back in November last year I posted on my confusion over the jubilation shown by the citizens of Spain as they elected Mariano Rajoy as their new political leader. Mr Rajoy’s strategy during the election campaign was to say very little about what he was actually intending to do to address his country’s financial problems, preferring to simply let the incumbent party fall on its own sword so that he could take the reins. It became obvious soon after the election that, despite his party’s best efforts to dodge questions, the intention was simply to continue with even more austerity.

Since that post I have continually warned that although Spain is obviously a different country to Greece in regards to how its problems have manifested, it still faces significant macroeconomic challenges that were not being correctly reflected in the bond market.

…. Spain which I consider to be the major unrecognised problem. The country has seen its yields tumble since December on the back of the ECB’s 3-year LTRO but there hasn’t been anything in the economic metrics of the country to support such action. Spain has 23% unemployment and still rising, the banking system is under-capitalised and still has unknown exposure to the country’s housing market collapse. On top of that the rising unemployment rates is pushing up bad loans in the banking system to 7.4%, a 17-year high, and is still rising.

As I mentioned this week, since I made those comments bad loans have risen further , house prices have continued to fall and the government’s debt position has worsened.

So it should come as little surprise to MacroBusiness readers that overnight the bank of Spain announced that the country has now fallen back into recession:

Spain’s economy is suffering its second recession since 2009, the Bank of Spain said, obstructing the government’s efforts to reorder public finances as it prepares the budget for this year.

“The most recent information for the start of 2012 confirms the prolongation of the contraction in output in the first quarter of this year,” the Madrid-based central bank said in its monthly bulletin today.

Spain’s gross domestic product declined 0.3 percent in the fourth quarter of last year, less than two years after emerging from the last recession. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy will present his 2012 budget on March 30, amid growing pressure from investors and European peers to rein in the deficit, which was 8.5 percent of GDP last year.

And so, once again, we see failings of economic logic creeping back into Europe. The reason that Spain’s economy is suffering is because the government sector is attempting to de-leverage in the face of the same behaviour from the private sector after the collapse of the Spanish housing market. You can obviously point to all sort of things that happened in the past and claim they never should have been allowed to occur. Where were the bank regulators? the macro-prudential oversight ? the fiscal policy in order to push against the housing bubble?. All good questions, but none of them change the fact that the Spanish economy is demonstrating its current behaviour because of the government sectors attempt to lower its deficit.

As I have explained previously in terms of national income, a country with a long running current account deficit has been borrowing goods and services from the rest of the world. In order to support this one, or both, of the non-external sectors of the economy will have expanding debt positions and due to this the economy tends to restructure around consumption over investment and production. Because the external sector is a net drain on capital from the country, the government and/or private sector must continually expand their debt in order to maintain economic growth.

In many cases this debt accumulation leads to asset bubbles, because the expanding debt drives asset prices which attracts speculation and in doing so accelerates the external borrowing. This in turn drives up national income, which in turn drives higher prices and further speculation. In the EuroZone, if either sector’s debt is accumulating faster than its income then at some point in the future a limit will be reached and the rate of debt accumulation will fall. This leads to falling asset prices and national income, which ultimately leads to a crisis as accumulated debts start to sour.

This is what we have seen in Spain. The private sector accumulated large debts on the back foreign capital inflows leading to a housing bubble. This bubble has since collapsed leaving the private sector in a position of significant wealth loss and indebtedness, the banking system holding significant and growing levels of bad debts and the economy structured around the delivery of a failed industry.

Prices for Spanish homes fell 3.4 percent in the first quarter from the previous three months as the euro area’s fourth-largest economy shrank and reduced mortgage lending crimped demand, according to Idealista.com.

Sellers cut asking prices for existing homes by an average of 2.9 percent in Barcelona, 1.9 percent in Madrid and 2.2 percent in Valencia, Idealista, Spain’s largest property website, said in an e-mailed statement today.

“Prices have continued to fall due to difficulty in obtaining mortgage financing,” said Fernando Encinar, co- founder of Idealista. “Legislation passed by the government in February to push banks to provision for real estate will result in similar declines over the remaining quarters of the year.”

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is battling to turn around a slump in the real-estate industry. His government forecasts an economic contraction of 1.7 percent this year that will push Spain’s unemployment rate, the European Union’s highest, to 24.3 percent. The government passed a decree in February forcing Spanish banks to make deeper provisions for losses linked to real estate in an effort to push down prices and boost sales.

The growing unemployment is leading to a slowing of industrial production, which means that even though the country is importing less it also appears to be exporting less. Combine this with the interest payments on borrowings from the rest of the world and at this point Spain continues to run a current account deficit which, in the most basic terms, means Spain is still paying others more than it is being paid back. That is, the external sector is still in deficit.

So with the external sector in this state and the private sector unable and/or unwilling to take on additional debt as it attempt to mend its balance sheet after an ‘asset shock’, the only sector left to provide for the short fall in national income is the government sector. If it fails to do so then the economy will continue to shrink until a new balance is found between the sectors at some lower national income, and therefore GDP.

It may appear logical to you that this must occur, and I don’t totally disagree, but that doesn’t change the fact that under these circumstances there is simply no way that the private sector will be able to continue to make payments on the debts it has accumulated during the period of significantly higher income. This is a major unaddressed issue.

This is why we continue to see a rise in bad and doubtful debts in the Spanish banking system which, under direction from the Government, banks continue to merge.

Spain’s biggest bank in terms of assets has been created after CaixaBank bought Banca Civica for 977m euros ($1.3bn, £817m). The government has amended laws to encourage mergers between banks, many of which collapsed following the bursting of the property bubble.

Banca Civica itself was formed by combining four troubled “cajas”, or regional savings banks. The merged bank will have 14 million customers.

CaixaBank will have 342bn euros in combined assets, deposits of 179bn euros and loans totalling 231bn euros, the bank said. The CaixaBank deal will be completed by the third quarter and will generate cost savings and other benefits of 540m euros by 2014.

The problem is that, apart from economies of scale, merging banks doesn’t actually help that much because impaired assets don’t suddenly disappear. The other issue is that Spanish banks have been large users of the ECB’s 3 year LTRO facility which means they have continued to load up their balance sheets with their own countries sovereign debt in order to participate in the carry trade.

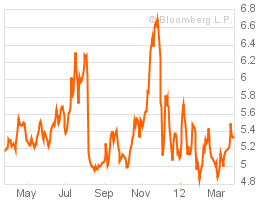

It is quite possible, as I explained above, that the LTRO was masking the true value of those sovereign bonds and that Spanish banks have made a terrible decision by making those purchases. Here are the current 10 year yields for Spanish government bonds, courtesy of Bloomberg:

If yields continue to rise, and I see no reason to discount this possibility, then Spanish banks are eventually going to have to front-up more capital to cover those ECB loans. Where exactly is this going to come from?

And so I am starting to get a bit of deja vu.

The eurozone’s public debt crisis is not over despite calmer financial markets this year, the OECD said on Tuesday, with a warning that the bloc’s banks remain weak, debt levels are still rising and fiscal targets are far from assured.

As the eurozone heads into its second slump in just three years, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said the 17-nation area needed ambitious economic reforms and there could be no room for complacency.

“Market confidence in euro area sovereign debt is fragile,” the Paris-based economic think tank said in a report on the state of the eurozone’s health. “The outlook for growth is unusually uncertain and depends critically on the resolution of the sovereign debt crisis,” it said.

….

OECD chief Angel Gurria has called for “the mother of all firewalls” – some 1 trillion euros – but finance ministers look more likely to agree to a level nearer 700 billion euros.

I’m sure we’ve been here before.

Perhaps I’m gloomy because it’s snowing, but I can’t help but notice that the headline, “Spain Follows Greece,” has the same rhythm as “things fall apart”.

I really wish it happened sooner rather than later – the suspense is killing me.

At the current rate what are we looking at, 2015? is Spain like Greece in ’09? (so maybe 3 more years)

There is a theory that total pain (TP) equals the integral of Pain at time t, P(t), over a period of time, or:

TP = ∫ P(t) dt

If so, in many cases, a sharp pain over 12 months can be actually less painful than chronic pain over 5 years.

Did you just make that up? It seems obviously correct, though.

I sort of made that up.

Wow! Such conservative thinking from a supposed non-conformist.

Point taken.

Will try to avoid math symbols as much as possible in the future.

It’s not the math; it’s the attempt to justify pain (almost always for others) that is conservative.

In that case, it’s liberal to think that the only fear is fear itself.

Fear not, you will survive.

This just in, lingering pain bothers you more. More at 11.

While I am completely impressed with the integral and do not in any way disagree with the analysis of Total Pain, the relevant set sadly seems not to be Total Pain, but just one of its subsets. The subset in question is, of course, what I will call Personal Total Pain.

So again, we are stuck with a formula that is a somewhat relevant abstraction but misses what seems to be the main motivator of human action, and that is the *interpersonal* distribution of Total Pain rather than the *intertemporal* distribution of Total Pain.

Again, though, *loved* the integral.

First off, it’s not always the case that short, sharp pain is preferred over lingering pain.

Secondly, even if you have many such cases, it’s not certain it’s often the case.

Thirdly, if, speaking of subset cases, as a group, not talking about individual case, you are prepared to face the short, sharp pain, you can also think about sharing the pain. Nothing is precluded here.

Finally, it’s a theory about pain, physical pain, economic pain, emotional pain, etc…something to think about, to think whether is applies or not, when it applies or when it doesn’t apply.

By the way, it took a little work finding that ‘integral’ sign.

What’s the best kind of pain? Sham pain (say it…)

Yes, but no shampoo — real poo or nothing!

Sham poo vs real poo – I think I have heard of debate before.

I’m not so impressed with the integral. Total pain has different units from pain in that expression: dimensionally, total pain = pain x time.

You may have a point.

Perhaps we can modify it by saying it’s not to be taken literally – that would be my first inclination, though I am sure some category-happy people will want to identify the different types and their corresponding relevant measuring-units .

If one is to be literal, one can question the following mathematical identity for those who are into identities:

Pain of amount x + pain of amount y = pain of amount (x+y)

The whole point is, I believe, not to avoid pain all-together, but to think about the possibility that maybe there is not just one scenario of pain, but two or three, etc, and can we know, at all, which one is less painful?

The pain in Spain is due mainly to the vain.

The problems with Spain are not easily addressed with fiscal policy. The problems are cultural and largely relate to the corporate state policies of the Franco regime which also included the need to pacify rebellious segments of the society by favoring development in Cataluña and the Basque country (at the expense of poorer regions). An autarkic industrial policy permitted widespread employment in non-competitive sectors and made dismissal difficult. The institution of a national health care and pension system covered basic needs. The value of the peseta internationally did not have great bearing on the daily lives of Spaniards.

It is not surprising that Spaniards prefer to have government jobs and state protection rather than to assume the risk of the entrepreneur. It is not surprising that recent regional elections favored those (communist parties, state subsidized unions) who articulate a return to the earlier policies that led to the present situation in Spain.

I agree with you Kenneth, but I really don’t think Franco is responsible for Spain’s woes today. The responsible crew is that which fabricated the “coffee for all” partitocracy/cleptocracy. If policies that address these two weights on Spain are dealt with swiftly, the situation could change by 2015-16.

I also don’t think Spain has suffered two recessions since ’08 or ’09 like Smith contends, but rather a permanent one. What a disaster this Zapatero guy has been.

I recently heard of Dinero B : the shadow, off-the books

economic transactions in Spain.

Are there too many “Dinero B” gimmicks for Spain’s good health?

Then, the “great salvator” after Zapatero is elected and… everything worsens! Come on, it is not just that you oversimplify. It is plainly ridiculous to place the blame in one person,. You look pretty much as a party-guy doing your advertising labour through the blogosphere.

good thinking Fernando.

Look! Over there! General Franco!

The pain in Spain remains from el Franco, not el banco.

The same refrain, whatever the name,

no matter what remains, no matter how explained.

We are made to be ahntrahpahnoors!

Anything less is lazy regress.

Which explains the rain on the plain in Spain!

Thou art a wit one must admit.

Silly, really, but beats getting angry :-\

What’s an ahntrahpahnoor? Some sort of fetish object?

I think so. Some explain it’s the magic that maintains the mahkit. But not in Spain where they maintain pain, encourage rebellious segments and otherwise refrain from the glorious gifts contained in the Great ahntrahpahnoor-ial Spirit.

Proposed Causes of the European Financial Crisis – Exculpating the Banks, the Financial System, the Institutional Structure of the Euro (and of course our dear Neoliberal Overlords)

Greece : tax avoiders ; (+ the welfare state)

Spain : Franco ; the siesta ; (+ the welfare state)

Portugal : Salazar ; the great earthquake of 1755 ; (+ the welfare state)

Italy : Mussolini ; “la dolce vita” (it’s Italian for lazy, don’t you know) ; (+ the welfare state)

Ireland : the English ; Guinness beer ; (+ the welfare state)

Rather than “cultural problems” I’d rather say “regulatory prolems”, since cultural sounds pretty much synonim of “unavoidable” or “time-consuming reversal”. The laws that regulate property, land development, investments, capital, and finantial activity favoured the relatively largest of all the housing bubbles. Unfortunately all efforts have been diverted to labour reform and the legal framework that makes Spain uncompetitive remains intact. We have to blame Central bankers who wrongly identify Unit Labour Costs and similar meaningless variables as the causes of spanish relative disadvantages. Central Bankers may know something about balance sheet or finantial issues but orangutangs know better about economy.

I meant Kenneth Alonso, not Fenando.

I meant Kenneth Alonso.

The problem is that, apart from economies of scale, merging banks doesn’t actually help that much because impaired assets don’t suddenly disappear. Delusional Economics

The larger the bank, the less likely its liabilities will be redeemed since it is more likely that money transfers will be between that bank’s customers. Thus larger banks are less likely to bleed reserves or need to borrow from other banks.

Spains biggest problem is that it built too many houses during the boom. If it left the Euro and devalued, lots of those houses would be snapped up by northern European baby boomers who want to retire in the sunshine. There’s a big culture of Brits and to a lesser extent Germans and Dutch retiring to Spain to live pretty cheaply and well on middling pensions. Britons are the largest foreign minority in Spain.

The Spanish a pretty hardy and bloody minded lot. Unlike the Irish, they won’t accept a decade of austerity just to stay in the good books, and unlike the Greeks, they have enough national self-beleif to see a first world future outside the Euro.

They’re not about to commit national economic suicide just so foreign bank bondholders don’t have to take a haircut, and if that means JPM have to pay all those CDS they wrote for Kyle Bass, then f*ck-em.

Let us hope that you are correct.

Personally, I’d think long and hard about retiring anywhere that has a youth unemployment rate of 60%, as Andalusia does at this point. Rich, foreign, elderly blow-ins + cash-strapped, indigenous youth? Not a good recipe for harmony, I suspect, unless gated communities are your thing.

And the loss of EU structurals funds to support poorer areas, especially in far-flung autonomous regions (the country is vast, for anyone who hasn’t been there), should Spain leave the euro, is likely to exacerbate the effects of the national austerity Rajoy is pursuing.

Lose-lose all round. What a nightmare.

“Rich, foreign, elderly blow-ins + cash-strapped, indigenous youth? Not a good recipe for harmony, I suspect, unless gated communities are your thing.”

It’s not really like that over there. Youth unemployment has always been shockingly high in Spain, it was around 20% even before the crisis, but crime rates are pretty low. And expats tend to live in the tourist areas, which have lower joblessness.

No doubt they’d prefer to stay in the Euro-zone, but they’re not about to accept mass poverty to do it. There are no easy solutions, thats for sure.

Why does everyone ignore the obvious? If a country is deleveraging at the private and public levels, as Spain is, the only other way to grow is exports. But Spain is saddled with an overvalued currency, the Euro.

Does anyone really expect the Euro to be so cheap in Spain (that is doesn’t cause chaos in a country where only 40% own their own homes, Germany) that it will drive exports?

So, if we leave exports out, that leaves a permanent fiscal transfer from the North to the South, of at least 6% of GDP. Is there any indication that the German voter, who was explicitly promised no monetization at the monetary policy level, will agree to send 6% of his GDP to the South?

Spain needs its own currency.

The Euro Zone does not have a mechanism for circulating investment capital towards some sort of export activity as the US has with military spending of approx a 1$1TRILLION/YR from the wealthy Coastal areas to the rural basket case states and the south in general. The virtual demilitarization of the Northern States with military bases decomissioned and civilian contractors almost exclusively relocating South of the Mason Dixon line has afforded a wonderful middle class lifestyle at the expense of the rust belt. Europe has yet to see the wisdom of procuring a similar circulation mechanism of wealth from solid, productive exporting nations such as Germany to the Margaritaville States of the Meditaranean.

Paul,

Such a novel idea, military Keynesianism, that certainly should work for long term economic growth and stability. Nothing more productive than building a half million dollar tank and shipping it half way around the world to blow up stone age families. Unless, of course, there is oil around the bend. But, it only works if you end up with the oil in the end. I would bet the Russians and the Chinese might be spoilers in this little game.

The Spanish Civil War never really ended. By default the best and the brightest left, mainly for Latin America. Spain has struggled to recovered from this loss, compounded by the decades of Franco. Now, Spain has been done in by the EU debt machine just at the time when they were beginning to recover. All those shiny new automobiles and half million euro flats really don’t mean much now. Very sad, because Spain, along with Portugal, are among the very few livalbe places on the face of the earth.

That war never ended in the sense that it just just a physical manifestation of the Class War, which is endemic to capitalism.

I take issue with these analyses. I do not see how the problem, at the accounting level, is inherent to Europe or even Spain, except superficially. In a previous post (19 March:”Understanding the Australian economy”) the author presented the following identity:

“National Income = Current Account + Private Sector Consumption + Investment + Net Government Spending”.

Now, one could consider an isolated economy where external trade does not exist, so the Current Account term falls away. Likewise, consider Investment to be foreign capital inflows and this term too can be omitted.

This leaves us only with the terms Private Sector Consumption and Net Government Spending to contribute to National Income. In a stable economy, the national income is balanced by an equivalent national product.

But a trigger event sets in motion a private sector demand for credit so the private sector levers up by borrowing from BankX against collateral. However, I see nothing that would prevent the government from also approaching BankX for loans, thus levering up against collateral too. Alternatively, it can issue ‘bonds’ for which the private sector will pay with borrowed money if the rates are attractive. At some point, credit expansion will slow. This probably occurs as debts near the level where they can no longer be serviced by productivity. Moreover, easy credit is likely to cause the economy to restructure around consumption over production, thus bringing that point forward. It is unclear how expanding government debt can fix this problem: the national productivity is simply unable to sustain the debt load. If the national debt is excessive, no one sector can compensate for the other. Taking on more debt just enables or prolongs consumption over production. It is only possible to remedy a shrinking national income with increased government spending if a nation has productivity ‘reserve’, i.e. before it has reached the level where productivity is insufficient to service debts. When no productivity reserve exists, the only solution is for the economy “…to shrink until a new balance is found between the sectors at some lower national income, and therefore GDP.” A default (of the nation to itself) amounts to something similar, but more precipitous. (Yes, if one wishes to subdivide, i.e. stratify, the terms, the analysis can be redone…).

I have pointed out before that the problem may be inherent in the national character or the national culture and becomes manifest as a productivity/consumption issue along with the resolve to address it. The national character/culture determines how debt and its resolution are approached.

I think the failings of economic logic come creeping back as our inability to address the proper rate of credit expansion and the felicitous unwinding of debt when necessary. Sector balances do not seem to help with this.

I agree very much with most of what this article says except with the beginning. The hypothetical “jubilation of spanish citizens with the victory of the conservative party is not real. I believe that it is just plainly normal that after 8 years of “liberal” government, spanish conservatives are glad to welcome back the conservative party. The rest of citizens, regardless of their ideologies are pretty skeptical about what the new government can accomplish during this mandate.

We’re a gaggle of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your web site offered us with useful information to work on. You’ve done a formidable task and our whole group shall be grateful to you.