By Philip Pilkington, a writer and research assistant at Kingston University in London. You can follow him on Twitter @pilkingtonphil

Recently I stumbled upon what appeared to be an interesting book entitled “Economics as Religion: From Samuelson to Chicago and Beyond” by Robert Nelson, an economics professor at the University of Maryland. This is a vital and interesting topic.

I asked a few heterodox economists if they had heard of it. To my disappointment one of them told me that, while the author obviously had a point, he was part of a school called the “New Institutionalists.” They are wedded to many of the neoclassical ideas which are in turn quasi-religious (witness, for instance, Bill Black’s coinage, “theoclassical”). Unfortunately, my friend proved right. While the book is interesting and contains many valuable observations, it is nevertheless orthodox in its thinking. The author, while firmly aware of many similarities between economics and religion makes two enormous mistakes both of which are tied up with one another.

First of all, the author does not properly deal with the true kernel of what makes neoclassical economic discourse similar to that of religion. In this regard he merely scratches the surface. He picks out many similarities between the two discourses and does provide a good case that economics has become a modern religious system, but he never identifies the aspects of neoclassical theory that lead to this.

Secondly, and tied to this, he ends up in many ways glorifying the religious aspects of economics. As Deirdre McCloskey writes in a blurb on the back of the book:

Nelson does not regard ‘theology’ as a cuss word, and so his detailed study of the theology underlying Samuelsonian and Chicagoan economics is not a putdown.

The reason that the author appears to uphold this view is that he seems to believe that economics could not be much else other than a theology. He seems to think that the nature of economic thought is to provide a set of moral guidelines that economists can preach. This seems odious. While I can fully appreciate that people do need moral truths with which to live their lives, I do not think it is the place of the economist to provide these.

In what follows I hope to show the key feature which makes neoclassical economics a theological rather than a rational doctrine – the key feature being the neoclassical concept of market equilibrium. In doing so I shall also lay out a different concept of equilibrium which, if properly applied, would ensure that economists could cease thinking in theological terms altogether. That this will take the form of a dialogue with Nelson’s book is because, while I firmly disagree with his methods and find his conclusions slightly regressive and even primitive, all in all he has written a very relevant and valuable book that I would encourage others to read.

Market Equilibrium: The Great Chain of Being Versus Intelligent Design

Let us first then examine two very different concepts of equilibrium. One of these is the one favoured by neoclassical economists and will hereafter be referred to as “market equilibrium”. The other is the one favoured by Post-Keynesian economists and will hereafter be referred to as “stock-flow equilibrium”. Let us turn to market equilibrium first.

The reader will probably be quite familiar with this notion of equilibrium as we are bombarded with it every day. Indeed, in a very real way it structures our morality and our thinking about the world around us. It is represented in this familiar form of the supply and demand diagram:

The idea is that equilibrium is determined by the interaction of supply and demand. The view implicit in the diagram is that we are in a marketplace of haggling buyers and sellers where the buyers make bids on goods while the sellers adjust their prices. Eventually when the whole process is finished the market falls into equilibrium which determines that price of the goods and the amount sold.

The economist Paul Samuelson, who will be discussed in detail later on, summed this up quite nicely in his introductory textbook “Economics” as follows:

Supply and demand interact to produce an equilibrium price and quantity, or market equilibrium. The market equilibrium comes at that price and quantity where the forces of supply and demand are in balance. At the equilibrium price, the amount that buyers want to buy is just equal to the amount that sellers want to sell. The reason that we call this equilibrium is that, when supply and demand are in balance, there is no reason for price to rise or fall, as long as other things remain unchanged.

There are many problems with this simple picture. The diagram, for example, assumes that if prices rise less of the good will be demanded. As we have discussed, not the case in many markets,. Think, for example, of the housing market prior to the financial crisis. In that market as price climbed ever higher these price rises themselves generated more demand for houses due to people trying to speculate on rising home values. The same phenomenon takes place across financial and asset markets and in many ways appears fundamental to the structure of markets.

What we are here interested in are only the metaphysical properties of this setup, not so much its inherent truth-value. We are interested in these because neoclassical economics when boiled right down is basically just a big pile of supply and demand graphs thrown one on top of the other. The economy is, in many ways, seen as being a giant supply and demand diagram – a giant marketplace tending toward or even already in market equilibrium.

The clue to the metaphysical properties of this setup is contained in the key concepts that an economy is either “tending toward” or “already in” equilibrium. The neoclassical market equilibrium analysis conceives of the economy in one of these two ways.

The strong or “general” equilibrium assumption is that economies are always already in equilibrium. Supplies and demands of and for everything, from labour to cat food, are always in balance and when a shock causes changes the economy adjusts pretty much instantaneously. The metaphysical kernel in this idea is almost too obvious to point out. The economy, indeed the world around us, is here portrayed as a perfectly harmonious utopia and we are implicitly warned not to mess with the Holy processes of supply and demand lest we fall into sin. Much like the old metaphysical Great Chain of Being the portrayal here is of a static world in which everything is in its right place and we are warned in a strictly moral tone not to question or mess with this structure.

The weaker or “partial” equilibrium assumption is that although the economy is thought to be out of equilibrium as it moves through time it is nevertheless always tending toward equilibrium. Whereas the strong or general equilibrium assumption presents a picture of perfect harmony, the weaker or partial equilibrium assumption presents a picture of a tendency toward perfect harmony. This idea of equilibrium is a teleological rather than a static concept, but the religious overtones are the same (one might compare it to intelligent design).

While the strong assumption of general equilibrium contains the basic message “you live on God’s (the Market’s) earth and it is already perfect therefore you should not step out of line with His rules”, the weaker assumption contains the message “you live on God’s (the Market’s) earth and, although it is not yet perfect, it is always moving toward perfection according to His rules and you should not break these”. It is basically a fight between the medieval Neo-Platonist theologians who posited a Great Chain of Being and the modern day Creationists who attribute teleological direction to the process of development.

Stock-Flow Equilibrium: A Practical Engineering Metaphor

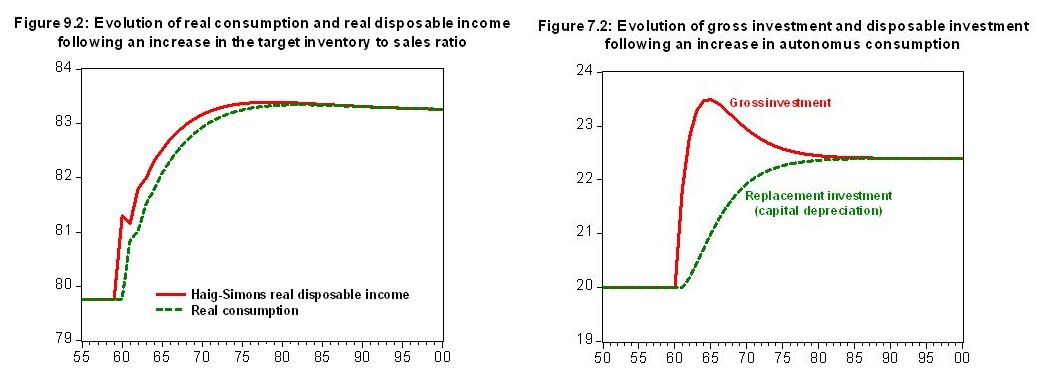

There is, however, another concept of equilibrium that although the reader might not recognise it in its economic guise it may well remind them of other sciences, such as engineering. This concept of equilibrium, a stock-flow concept, is illustrated in the two following graphs (click to enlarge).

The perceptive reader will notice that these two graphs, unlike the neoclassical equilibrium approach, refer to specific variables rather than just supply and demand in the abstract. The graph on the left refers to disposable income and consumption, while the graph on the right refers to two different forms of investment. The reason that these graphs refer to real variables is because they are not really concerned with metaphysical abstractions that are then applied to data after the fact, as is the case with the neoclassical approach. Instead, as in engineering and other sciences, they are concerned with how a change in one real variable affects another variable.

In the graph on the left we see that an increase in disposable income leads to an increase in consumption. This is simple enough but we should note that it also contains a concept of equilibrium. Take a look at the bottom left of the graph where the line begins (the “Y-intercept”, for mathsy types). The X axis – that is, the bottom axis – depicts different time periods in years. From 1955 to 1959 the levels of disposable income and consumption remain the same. This is referred to as a stock-flow equilibrium point. Next, a shock occurs – maybe an increase in government spending – and disposable income starts to rise after 1959 and drags consumption up with it. However, once this new flow of income stops increasing around 1975 the graph moves once more toward a slightly unstable equilibrium. This is even clearer in the graph on the right-hand side where by around 1985 the two variables have reached a new perfectly stable equilibrium after a shock of new investment in 1960.

These ideas can be better explained through the bathtub analogy that the economist Wynne Godley used to use; Godley being the man who fully formalised this approach to economics in his seminal work, co-authored by Marc Lavoie “Monetary Economics”. Godley asks us to think of economic variables as one would a bathtub. We fill up the bathtub to a certain level – call this level X. If we pull the plug the level of water starts to fall from point X. However, if we turn on the tap and ensure that the rate at which the water is flowing into the tub is the exact same as the amount of water flowing out, the water-level will remain at X. The bathtub can then be said to be in stock-flow equilibrium.

This conception of equilibrium is in no way metaphysical. It implicitly contains a vision of the economy as a collection of interacting stocks and flows. Our job as economists then is not to meditate on the harmony of supply and demand but instead to study how these variables are interacting and advise macroeconomic policy based on this. This is certainly not the economist-as-priest that Nelson, stuck in the neoclassical paradigm, assumes is inevitable in his book.

Today many neoclassical economists insist that their market equilibrium models are indeed stock-flow consistent. This is never the case and simply shows how, stuck as they are in their metaphysical stories about market equilibrium and rational agents, they completely muck up their analysis of the economy and cannot even get things straight in their own minds. There is an interesting history as to why the economics profession side-lined the stock-flow equilibrium approach in favour of the backward market equilibrium approach and we recap it below.

John Maynard Keynes: Aspiring Dentist

Nelson’s section on Keynes and the Keynesians is not only rather unfair but it also completely ignores Keynes’ own students who had very similar ideas to those above about how the economy operated and were just as hostile toward economic theorising characterised by assumptions that the economy is a giant market perpetually moving toward or already in market equilibrium. Nelson instead focuses on some of Keynes’ throwaway essays that he wrote for a popular audience and holds these up as proof of Keynes as religious seer rather than the rationalist of the General Theory.

Why he does this we can only guess. But it appears that he found it hard to detect theological elements in the General Theory and so in order to hold his contention that economics is in essence a religion together he had to focus on the popular essays instead. Keynes himself was acutely aware that economics was an odd profession and he explicitly made it his task to bring it back down to earth. In the very essay that Nelson focuses most on, that is “The Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren” Keynes famously writes:

If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people, on a level with dentists, that would be splendid!

Certainly this is not something that a person trying to maintain for his profession the status of a priesthood would write. Keynes’ own students were largely in agreement. Joan Robinson, for example, while studying under Keynes wrote an essay entitled “An Economist’s Sermon: Economics is the Dope of the Religious People”. Again, hardly the words of a person who wishes to see the economic theology remain intact or someone who is working within a group that does not recognise the theological underpinnings of the orthodox school.

Nelson ignores the British Keynesians and those that followed in their tracks and instead looks to the American neoclassical-Keynesian school – the “bastard Keynesians” as Robinson called them – as the inheritors of the tradition. Here it is not hard to detect elements of the old-time religion and Nelson focuses specifically on Paul Samuelson’s introductory text “Economics” as the Bible of American Keynesianism. In this regard he is certainly correct as this type of economics is replete with supply and demand graphs and other metaphysical notions. But Nelson does not seem to appreciate why this religion was held intact by Samuelson and his allies against the new stock-flow approach that would have rationalised the discipline had it gained dominance.

In order to understand this we must discuss a now rather obscure Canadian economist who studied under Keynes called Lorie Tarshis. Tarshis was trained in the Keynesian tradition of Keynes himself and his students; the tradition that emphasised the economy, not as a giant market, but as a system of stocks and flows ever-expanding and contracting. Tarshis took it upon himself to bring this new economics to America, but unfortunately the whole enterprise turned ugly very quickly.

Tarshis published an excellent Keynesian textbook entitled “The Elements of Economics” in 1947, well before Samuelson’s “Bible” was released. At first the orders came pouring in from universities across the US and it looked like the new economics was set to come to America. But then, alas, the red-baiting started. Right-wing thinkers began to ferociously attack the book as a work of Communist propaganda in reviews and articles. William F. Buckley Jnr, the notorious right-wing propagandist, wrote a long attack on Tarshis which amounted to being a complete and utter stitch up. Colander and Landreth in their paper “Political Influence on the Keynesian Textbook Revolution: God, Man and Lorie Tarshis at Yale” relate that Tarshis wrote:

That bastard Buckley – I get so angry when I think of him, because, you know, he’s still parading his objectivity and concern for “moral values”, and so on. The amount of distortion is enormous. He would pick a phrase and tack it onto a phrase two pages later, another page later, another page four pages earlier, and make a sentence that I couldn’t recognize as anything I’d written –I was only able to see it when I had my book in front of me, and I could see where they came from – and make it seem as though I was no supporter of market capitalism, which I felt I always was.

Yes, there were those who did not want the new economics to gain any traction at all because they fully realised how it would completely overturn their old time religion. Buckley, while not a terribly intelligent man, knew instinctively that market equilibrium, the Great Chain of Supply and Demand, was a good conservative doctrine that held everything in its right place and ensured that no uncomfortable questions were asked about the structure and setup of society. The Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek, to take another example of the response to the new economics which concerned itself with the consequences of the overturning of the old market equilibrium ideas, summarised nicely what the old priests thought of the new ideas:

Some of the most orthodox disciples of Keynes appear consistently to have thrown overboard all the traditional theory of price determination and of distribution, all that used to be the backbone of economic theory, and in consequence, in my opinion, to have ceased to understand any economics.

What Hayek really meant, of course, was that they had ceased completely to do the type of economics that he and his caste preached. Paul Samuelson, on the other hand, took a few of the Keynesian ideas in vulgarised form and stuck them onto the neoclassical market equilibrium edifice, thus insulating the old religion from rational criticism by integrating to some extent the new ideas. He did this partially because he liked basking in the mystique of religion, but also partially because he was scared that the McCarthyites would go after him should he commit the same heresy as Tarshis had. Collander and Landreth document Samuelson’s response to the attack on Tarshis:

Samuelson, in answer to the question “What kind of attacks did your book get and how did you deal with it?” responded that “For some reason that I have no understanding of, the virulence of the attack on Tarshis was of a higher order of magnitude than on my book, but there were plenty of attacks on my book, and there was a lot of work done by people. Also I wrote carefully and lawyer-like so that there were a lot of complaints that Samuelson was playing peek-a-boo with the Commies. The whole thing was a sad scene that did not reflect well on conservative business pressuring of colleges.”

Samuelson claims not to know why his book did not come under the same sustained assault as Tarshis’ but in light of the above discussion it should be obvious: Samuelson kept the Great Chain of Being intact. Samuelson was, at heart, a priest and the right-wing propagandists did not feel threatened by him.

Conclusion

Nelson is perfectly correct in that neoclassical economics is closer to religion than to science and he has done the world a service by publishing his book. However, tied as he is to the Samuelson neoclassical school he has concluded that this is not a particularly bad thing. He is, in a sense, perfectly comfortable with his status as priest because he simply ignores the alternative.

It is, of course, up to the reader what they think economics should be. Should it be a collection of fairy tales about harmony and market equilibrium or should it be the serious study of stocks and flows at a macroeconomic level? The reader can decide that for themselves. Being what I consider a child of Enlightenment I believe that religion has no place in economics but, just as some people prefer Intelligent Design to evolution, others are perfectly free to disagree. What they must understand however is that, first of all, what they are engaging in is theology – the Intelligent Design crowd are content in admitting that and the market equilibrium theorists should be too. Secondly, they must understand that there is an alternative ready and waiting should they ever decide to emerge from the Dark Ages. Then at least we are in a position to have an honest debate: what should economics be, religion or science?

Another execellent piece. I’ve often wondered about Samuelson’s strategy for drafting his book was influenced by the general need to strangle Keynesianism as quickly as possible and place neo-classical economics on a “scientific” footing to return that idea to it’s pre-Depression dominance. Your article makes it quite clear that Sameulson was not going to end up like Galileo.

I’m reading Justin Fox’s The Myth of the Rational Market and still can’t believe how much of modern “scientific” economics comes down to nothing more than someone’s ipse dixit. But that’s the nature of religion, then, isn’t it? I think the wealthy wanted to ditch the New Deal, FDR, and Henry Wallace ASAP once World War II was over; and the post-war economy and a ramped-up Cold War gave them plenty of cover (and power) do to so. The cultural history of American capitalism also made it easy to eventually write-off the New Deal as either a bad idea, or a one-time fix to a once-in-a-millenium crisis.

About Buckley, I was a bit surprised by your comment about his intelligence. Over time I’ve come to reject his ideas and see the flaws in his arguments. But having met him once, I’d say that his challenge was more moral then intellectual.

Daddy’s oil money was what Buckley was trying to defend.

He would have had it in for Tarshis for a number of reasons, most especially his view that in a democracy the people can change economic policies by popular vote. Harumph!

Funny how it seems that CIA is some kind of right of passage of hardened conservatives in USA…

Economists would have been less surprised about the vicious attacks on Keynes’s students…

…if they had really paid attention to Veblen. The psychology he describes among the Leisure Class is one which *requires* the Leisure Class and their puppets to make vicious, dishonest attacks on anyone who proposes something fair and sensible.

Buckley never struck me as clever. He had a nice accent and spoke nicely, but he couldn’t deal with rational argument. While I don’t agree with everything Chomsky says, in his tete-a-tete with Buckley on the Vietnam War, Buckley comes across as a proper idiot. I imagine he did every time someone wasn’t fooled by his charm and actually threw down the gauntlet.

Guess I played the fool that night! ;-)

Regardless, the more I read about the return of neo-classical economics, the more stunned I am that no effective rebuttal could be made to nip that nonsense in the bud. Even given Steve Keen’s point that neoclasscial economics spreads through undergradate economics and business programs by a sort of intellectual bait and switch in which the students are allowed to assume the existence of proofs their professor know (or should know) don’t exist, I find it fascinating that this religion has spread so far and wide. From what I can see, it’s now become like Scientology among academics (but without the aliens) in terms of the brutal conformity enforced on the economics departments.

All of which suggests a sort of nod-and-wink conspiracy among academics in the end: An unspoken agreement to avoid attacking certain professor too harshly; to avoid promoting heterodox thinkers or Marxist critics; to subtly support libertarians even while pretending to ignore them. (Samuelson’s relationship to Friedman comes to mind here.) And of course there was the open and flagrant flogging of these ideas by the wealthy and their media channels.

Getting back to the details of equilibrium, I often found the idea of the sort of Newtonian balancing of forces rather crude for what is essentially an exchange. The competing rates model is indeed better, but it too seems rather clumsy. As an old chemist, I often wondered if the idea of chemical equilibrium, i.e., the balancing of rates of conversion between two or more states, wouldn’t be still better, since it is a closer analog to the passing of goods and currency. Do you know if anyone has tried that model?

Yes. To see how the profession “engage” just look at Krugman. He writes Minsky papers without citing Minsky scholars. Its awful. I’m not sure what the motivation is, to be honest. I think it might just be distaste for anything that doesn’t smack of theology.

Regarding equilibrium. I think the further the economists get away from the natural sciences the better. I don’t think equilibrium is a useful concept at all. But in order to “speak” in models its an awful lot better to use the stock-flow approach, I think. Very little baggage.

Hmm! I like the idea of an “economic dynamic equilibrium”; a nice analogue of many chemical reactions – called reversible reactions since they proceed from reactants to products (goods and currency as you mention) or from products to reactants – and we measure the concentration of one (or many) of the reactants and one(or many) of the products versus time. Simply:

• Since this reaction is reversible, when C and D are produced from A and B, they may react to form A and B again using the reverse reaction.

• After a certain time, the concentrations of all reactants and products remain constant.

• The concentration of the reactants never falls to zero.

So, in dynamic economic equilibrium, capital and output would also grow at that same rate, with output per worker and the capital stock per worker with the same ratio (?). And, we can control the rate of the reaction too!

Though, inserting the money creation (expansionary monetary policy by Endogenous means) creates a whole new dynamic variable – and, likely, an exothermic reaction.

This equilibrium goes by another name in environmental economics.

“Sustainability”, it’s called.

“He had a nice accent and spoke nicely,”

It was the faux British-Boston Back Bay accent effected by American snobs. Buckley was an insufferable snob of the first order.

*Free Markets* are of course our new religion, whether or not any particular philosopher proclaims them to be or not to be. And just like religion, we don’t even practice what we preach, or more to the point, we practice it only when it benefits us. Go figure. We humans are funny animals, all full of ourselves and caught up in the drama of saving the world…

…from ourselves.

For those wondering about the Great Chain of Being:

http://tudorblog.com/2011/10/01/the-elizabethan-world-picture/

I like your stock-flow equilibrium, the reference to real variables. I like the progressive and enlightened way in which you (and Keynes) open yourself to the Popperian notion of falsifiable statements. Heck Phil, I even like you. But, you and the enlightened have a challenge ahead of you: the economics of political dogma – monetary policy and political power. It is like Galileo and the Vatican.

When William F. Buckley Jnr, was attacking Tarshis, he wasn’t attacking Tarishis’s ‘new economics’ per se, but neither was he morally or intellectually defending the orthodoxy of neoclassicism; he was protecting the post war politics of modern monetary policy and the economic power it wields.

The vested interests of “free market capitalists” are so wedded to the opaque economics of the neoclassical models precisely because it is religious, because it requires political faith rather than reason, because it can’t easily reveal that powerful economic change agents cause disequilibria, from which they then profit at the expense all others. So, now your challenging the worst type of economic religion: moneyed interests.

Ah yes, the “every national currency pegged to the USD pegged to gold”. The very thing Keynes railed against because he foresaw it having disastrous effects on the world economy given time. Too bad his health was failing.

I do wonder if the Euro could be turned into something similar to what Keynes suggested for the world economy, but limited to operating within EU. A special cross-border trade currency rather than a domestic currency for all Euro nations.

Interesting as usual Philip. My take has long been that economics (and business teaching in a wider sense) is part of a wide control fraud as most religions have been. Questions remain on just what the science-based democratic position from which we argue is in respect to this and how little any of the perspective is in practice.

The two main divisions in argument concern immanent critique in terms of basic assumptions made and analytic critique that discovers and argues from competing basic assumptions. We have know since Sextus Empiricus that many equally powerful arguments based on different assumptions can usually be made – the ‘answer’ then was to achieve a special mind state probably impossible. The general treatment of this is the generic frame of reference (paradigm in more popular literature).

Whilst I agree with Bill Black, Michael Hudson, Steve Keen and so on – and most written here – our position is much less rational than we like to think and we are not finding ways to talk about the real practices in something approaching entirety ourselves – not least for want of space and time! Most rational positions turn out to be much less rational than were assumed at the pivotal time (Foucault and cast of thousands).

The arguments we are making remind me a lot of UK Old Labour (Wilson, George Brown) – a big twist is the debt bubble and why that matters – and we are evading many of the unspoken assumptions of our opponents – notably that they do not believe in democratic foreign policy and do see economics about control through unspoken assumptions of military-elite power and the importance of staying on top.

My contention is that we do not have the open speech acts of science available to us – even science isn’t perfect in this regard but any idea we are engaging, say (the literature is legion), Habermas’ Weberian ideal type of speech act where only Reason is in play is a non-starter and dangerous illusion. We cannot even rely on a definition of scientific method and deep down we don’t understand that even particle physics is a system of inter-related accounting devices that sound much more definite than they really are.

Much could be said on the general poor understanding of scientific methods in the social sciences (literature legion) and the complexity of scientific philosophy (legion again and often very difficult – see Ludwig for an example, or ‘scientific realism’ at Stanford EP on line). Many former colleagues in science tell me it is now impossible to learn some specialisms through taught basics, and it is often the case that only experts in a field can really talk to each other and possibly colleagues in overlapping areas – this within disciplines, not between physics and chemistry.

What I suspect is ‘we’ do not have a scientific case – just one much better than the theo-cons. Our own case has religious elements – the debt jubilee of David Graeber’s ‘first 5000 years’ is an example – even if we want a sophisticated, systemic relief (religion, even to an atheist like me isn’t all bad). What could be more democratic, more in keeping with freedom, than paying off private debts in current circumstances?

I suggest we need our plan in the open and to think of this part as less scientific than our approach to implementation, evaluation as we go along, measurement of effects and in order to change and control to desired ends as the scientific part – including a means to restrict the activities of thieving bastards in the system. We might be able to implement without changing the existing overall system (just a thought) and need to explain how we don’t mean to have the usual mess of apparatchiks involved or big government (not Soviet, not of the rich).

What we can address scientifically is such as where does money end up if we monetise debt (the billionaire club) and where it will end up if we give to the relief or ordinary people (end point relief or productive investment). We should not over-claim our case as scientific – it’s about the reclaim and survival of democracy. And, if you think about it, we can appeal to the religious vote too! Graeber has the outline.

An alternative approach of course is to suggest that we need better religion in economics. I think Catholic Social Teaching, which calls for social justice,has something to offer contemporary society.

Philip to be honest I’m disappointed here. I can’t see how “stock-flow” equilibrium is much better than market clearing equilibrium. Neither exists in reality.

I would want to see a much more mathematical modernised Schumpeteriansism – something that recognised the importance of technology and resource endowment and gave them a more central role. It also skips the whole financial/real dichotomy business.

What is really diabolical about the market clearing model, is that ignores the consequences of long term market disequilibrium (e.g. sustained unemployment) by denying that they are possible. It chooses not to even study disequilibrium (for instance the reserve army of the unemployed effect of driving wages to subsistance) by denying the existance of such a state. How does stock/flow analysis help much with this?

P.S. I’m not saying stock/flow analysis is not valuable – it is. What I am saying is that it is far from sufficient and it is far from the crux to determining why economics is a religion. Economics is a religion because it assumes it knows the answers via intraspection rather than closely examing external reality to find the answers. Full stop. The worst example of this is not neo-classical economics it is “Austrian” economics.

My own approach to economics would be much more to see the system as a dynamic interactive system with many feedbacks both positive and negative. One of these is the market price mechanism, another is the stock flow mechanism. Another is the human, firm and product lifecycles. Another is the complex interaction of tehcnology and resources. Another is geographical interactions, especially urban development. I seriously don’t believe we can begin to understand such a complex system without modelling the parts – when I retire I will start building complex object based simulation models, in the hope to win some understanding.

In the meantime, I will take the instinct of a Krugman, picking and choosing between various partial equilibrium models as seem appropriate to the subject under discussion (and keeping clear that that is all we have) than a DSGE freak who thinks their model is the real world.

If economic reality is too complex to be modeled in a useful way, then the intuitions of someone who has a history of reliable predictions is the best we can do. To become such a reliable predictor ourselves we might want to study economic history a little more than the various incomplete and simplified theories.

I think economics would improve by taking account of black market and illicit transactions, because money can be laundered.

I take one look at those graphs and my very next thought is “Critically damped 2nd order differential negative feedback”. Of course I only barely passed my control-systems engineering subjects, so don’t rely on me for the maths;however, compare them to the wikipedia entry (you will need to look at it upside down).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Damping_1.svg

Believe me it is more complicated than that – but Philip was only showing single partial analyses not whole system simulations. There are not only negative feedbacks – there are also positive feedbacks (bubbles)! Sometimes these need to be actively damped, you can’t rely on passive damping.

The Bible forbids counterfeiting and usury from one’s fellow countrymen and especially from the poor YET our “private” money system, the banking cartel, is based on all of the above! Indeed, the poor are not charged 0% interest as the Bible commands but are charged the highest interest!

So just what religion is neo-classical economics based on?

probably some demon-worshipping orgy of debauchery with Satan himself as a hollow-eyed goat-legged ringleader shooting hellfire from upraised arms and chanting through a vacant sadistic grin the Demonic Sadistic Godless Equation over and over as worshipping hoards count their usurious loot stripped from righteous men through malicious deceit and trickery. God will know what to do with this carnival of crime and lust, at a time and place of his choosing.

F.Beard!!!

They don’t call it the Bank of Satan for nothing.

Machiavelli-ism. I am one to see the bathtub analogy however, the tub becomes the vessel in which we hold economic thought. The tub now represents a drive toward balance when, if applied to the term ‘equilibrium’ in the man made construct of economics, we should be looking at entropy as driving away from equilibrium.

Economics is not applying today as it has been captured and mechanically rolled out by the princes of finance and is not naturally correcting under the ‘laws’ of economics. The invisible hand has been shackled and enslaved by the princes.

The current problem is that the princes are finding a way to dole out just enough scratch to keep their subjects in line to achieve their goals. This, of course, requires the application of all manner of dogma, historical re-write, religious closeness and propaganda of any shade to keep themselves in power.

So indeed, many graphs and applications of ‘science’ may match what we see in numbers or symbols – the benefactors (those wishing to keep power and privilege)- will do all in their power to sway the hearts and minds of their subjects.

Economics as a science is like Scientology as a religion.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6n8EmGBhfSU

Keep dancing Phillip

That’s how Nelson’s book came across to me, not so much as a prescription for economics, but as a description.

Other excellent books in the same vein are Carroll Quigley’s The Evolution of Civilizations, Michael Allen Gillespie’s The Theological Origins of Modernity and Nihilism Before Nietzsch, and Stephen Toulmin’s Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity.

Anybody who looks to economics, or any scientific endeavor as far as that is concerned, for sure truth practices a brand of metaphysics that looks a lot more like dogma than unbiased, disinterested inquiry.

From what I can tell in my short study of economic theory, but in my lifetime study of humanity, economics is used as justification for all of the greed, lust, and hatred of the natural world being expressed by modern man. The ‘market’ removes all moral and ethical responsibility, and books and theories and graphs and models are all made to legitimize this train of thought. It imagines itself as a perfect world, while in reality it is the birthing pool of a world of nightmares. We may very well extinguish all life on this planet, undoing 13 billion years of null-entropic growth, in our quest for illusory artifices and faith in our own ingenuity. Modern economic thought is a disgrace and insult to the DNA legacy that every living creature shares. What a wonderful world we are creating according to the whims of the ‘market’. How great it will be to sit on our piles of money, surrounded by death.

Games and ideas are wonderful fun, but when we make them the model for our reality we invite disaster. Following the religious teachings of economic theory is akin to basing world civilization on the rulebook of a board game.

It’s a good rant. But I tend not to believe “the market” does any such thing, what does that is very specific manmade social structures. Limited liability, not holding companies to account for externalities, yet using the government to enforce “property rights” for these same companies etc.. The rules of the game create the results and not some vague “the market”.

“Games and ideas are wonderful fun, but when we make them the model for our reality we invite disaster.”

The map is so fricken not the territory at this point that …

Phil’s last name is misspelled in the post’s title…

ha! beat me to it.

Very interesting Lambert and Phil, but a tough topic to blog about. I did take a look at Nelson’s book but decided not to buy it as I was working on my own long essay in this region, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry Market.”

I would recommend to you a better book considering the similarities of religion and economics as we’ve come to understand the later, especially, in the late 20th and early 21st Century, and I’ve never seen it mentioned on this good site: Mark C. Taylor’s “Confidence Games: Money and Markets in a World Without Redemption,” which came out in 2004. The author later headed the religion Department at Columia University, but that shouldn’t deter NC followers at all, he’s not your typical religion department head, and I’ll vouch for his fluency in economics; His chart on page 178 of the Mortgage Market in a Chapter entitled “Specters of Capital,” levels the charge of a pyramid scheme, and echoes his handling of the collapse of Long Term Capital Management, which he portrayed as having had “‘a vision of zero capital and infinite leverage.'” (He is covering ground on the work done by Dunbar and Lowenstein.) Not bad for something which came out in 2004.

Let me add my own perspective to Taylor, who is the most secular head of a religion department you’ll probably ever come across, and who obviously had good fluency in derivatives and their dangers well before the regulatory “community.” In the sense that Paul Tillich defined faith/religion as an individual or society’s “ultimate concern,” its hard not to argue that the capitalism of free markets represented by the Univ. of Chicago and the Washington Consensus stands as the ultimate value and reference point of American Society.

Dean Baker may want to bring “the market” down to the mundane level of just an economic tool, but that’s not its usuage or meaning in everyday life or even among the economics profession. If anyone cares to follow closely the chain of reasoning of why, exactly something can’t be done by “government” about the economic situation, the objection of “the markets” or the violation of the supposedly laws behind them is almost always invoked. Let me refer Mr.Baker, and NC readers to that great friend of this sense of “the markets,” one Thomas Friedman, who is fond of invoking this phrase, that “the two most powerful forces on earth are Mother Nature and The Market.”

Now I have great distance and differences with Friedman, and on this with Baker, and I refer readers to just how ill-defined those “markets” actually are – to the work of John Kenneth Galbraith and his two tier structure of the economy in the old industrial one, and Frenand Braudel’s good handling of how hard it is to define the term, esp. in Volume 2 of his great “Civilization and Capitalism.”

Yet, please readers, don’t forget, that the elevation of the Market, and its closest observers, Wall Street, to the near religious level did coincide with the rise of the religious Right, giving us a “moral” economy with lines of explanation very close to that of the ante-bellum US, and shading into the Social Darwinism of the Gilded Age.

While I don’t always agree with the ahistorical constructions of cognitive linguistic George Lakoff, I have to admit his handling of contemporary political economy through the eyes of the religious Right in his book “Moral Politics,” is largely correct, and takes us back to the 1840’s in the US with chapters entitled “Keeping the moral books,” and “Strict Father Morality.”

One of my great objections to those who, however unknowlingly, turn economics into a religion, and link a market economy to deeper and older “foundations” for morality and religion, is that capitalism as I’ve come to know it is a dynamic system set on overturning existing real structures (and older moralities too?) by its very nature. If, as Dean Baker seems to believe,markets are a mere tool that we can pick up and wield in new value (read progressive) directions, consider the closest example which any one society has ever come to the pure free market ideal: Jacksonian America of the late 1820’s and 1830’s, a world of millions of small merchants and farmers, with some 70-80% of citizens engaged in some form of market farming, where if you worked hard, you could morally reap the just rewards…just take that world and that simple view (which is the view of the Religious Right today…) and consider the farmers status and revolt of the 1890’s, or the shocking percent of the remaining farmers as the edge of the New Deal in 1932, where something like 30-40% of their still considerable numbers were “tenant farmers,” hardly the ideal basis to continue the democracy of the Atlantic republican tradition…

and let’s carry this line of political economy thinking right into today’s world, the Jefferson Lecture of Wendell Berry from April of 2012…where farmers have disappeared, and Berry looks at the “morals” of the political economy of today and announces that he sees two great historical trends in capitalism: “the urge to eliminate workers and toward oligopoly and monopoly.”

And if that old time religion, religous as applied to the political economy of the 19th century, rested upon hard work, moral reward for that work, it also rested on thrift and austerity, the Old Protestant Ethic, however disputed, which has a very tough time squaring itself (and I am no austerian in the contempoary meaning of the term)with the elevation of private debt to a basic “fueling” principle of the private economy…and I’ll close by linking that back to Taylor’s book “Confidence Games,” where he traces the old Medieval fasination with alchemy forward to the unspoken hopes for a modern financial machine of perpetual motion, of “infinite leverage upon an ever shrinking foundation of capital-collateral” – about as far as you can get from the world Jefferson hoped for…a debt fueled private sector dream at shocking incongruence with the austerity which the private sector would like to impose on government spending.

If you are a religious conservative trying to preserve “the old values” and think modern day capitalism is your “horse,” I dare you to read Taylor and not come away shaken.

Even if Nelson makes a weak argument about Keynes theories being theology, that doesn’t make them science. Until I see a strong argument that any economic theory is science, I’ll assume Nelson’s thesis is essentially correct.

How I can best utilize my life to make a contribution to society is essentially a spiritual question. Despite dubious claims to measure outputs, economics doesn’t provide useful guidance about what to do with one’s life or about activities that might enhance the quality of society.

Most economic arguments about whether or not to expand the public sector simply beg the question. They are only worthy of attention when one gets specific about the activities one proposes to add or eliminate. My judgements on the value of those activities are primarily “faith-based” – they depend on my trust in our system of government and my views on developing a society worthy of living. I’d love to have a more enlightened way to look at these issues but I’ve not found it in economics.

It’s always interesting seeing two theologians arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. However since the author is leaving it up to us readers to decide what economics “should” be, then I will decide that it simply goes away, period.

The last thing we need as a species is a bunch of self-annointed intellectuals who are prone to corruption and delusional thinking sitting around trying to decide how to govern people’s behavior through policy, like astrologers advising a monarch. Even if there are one or two good ones in the lot, the overwhelming majority are fallible or simply evil.

Dynamic Equilibrium would probably be a better term. It at least captures the idea that the ground against which we measure things changes over time. The changes can be externally driven or the unintended consequences of policies enacted under a flawed theory. In any case, as time speeds up due to technological innovation it becomes necessary to treat those things formerly considered constants as variables.

It’s a shame more economists haven’t read James Grier Miller’s “Living Systems.” For anyone attempting to place economics on a scientific footing, this is essential reading:

http://www.panarchy.org/miller/livingsystems.html

The principle error most economists commit is to not search outside their own discipline for insight and inspiration. Most of what I see are critiques of one economist vs. another citing yet more economists in support of their argument. In that sense it is like a religious debate between various doctrines. I suggest that what awaits us (driven by present dire circumstances) is a fresh approach akin to Khun’s Paradigm Shift, although where it will come from is anyone’s guess.

That said, I’m optimistic that it will occur. Prior to the internet the only venue for discourse was through academic literature and personal contact. Now everybody has a dog in the fight, and while this may cause distress and irritation (especially to vested interests), in the longer run it just might produce something of value.

The new paradigm is that any proposed economic ideology must now build itself upon a foundation that understands human nature is ambivalent. Failure to do so leaves the ideology open to utopianism and hence religion such as Marxism, Communism, Neo-Liberalism and Libetarianism. See Christopher Boehm’s book “Hierarchy in the Forest.”

“The new paradigm is that any proposed economic ideology must now build itself upon a foundation that understands human nature is ambivalent.”

Exactly. A variable, not a constant. I would push this notion even further and suggest that we now have the ability to change the underlying neurological substrate that governs our innate behavior, effectively tunneling through the evolutionary barrier of selection over time. Cell phones are an early example of this – a prosthetic form of telepathy that effectively mimics the real thing.

Now?

The Buddha taught such a technique over 2500 years ago. Alas, like all great sages he became deified and his methodologies forgotten, but in some secular schools of meditation his original teachings are still passed on.

We do have the ability to rewire our own neural pathways. It is very hard work, something that is anathema to our modern society.

The apparatus of our enslavement is the tool of our liberation.

Philip stated: “What should economics be, religion or science?”

Science is often conceptualized (in public–as well as seemingly supported by Philip) as a pure accumulation of knowledge: that is as a closer approximation to the truth than any earlier theory achieved. Historical changes in science were often seen(especially by logical empiricism) as nothing more than than the account of uniform progress toward better science.

But as Thomas Kuhn argued in his 1962 analysis, “The Structure of Scientific Revolution” science is, in fact, not uniform, but shifts through different phases—and Kuhn maintained that such shifts were not so much making progress toward truth but “as changing paradigms.”

For example, as Feyerabend has argued in “Against Method,” Galileo’s propaganda (I.e his rhetorical ability to convince his contemporaries of the superiority of the Copernican theory over the Aristotelian on the basis of uncertain and partly refuted data—points up the crucial role of seduction in the scientific enterprise. In addition, Galileo was also brave enough to take on the risks of such a new paradigm.

Such an example seems to indicate that truth is, in fact, not the main concern which drives scientific progress and that scientific knowledge did not change through confrontation with hard facts– but rather is largely a social struggle between contending interpretations of scientific communities.

As Vattimo and Zabala argue in “Hermeneutic Communism,” Luther’s revolt against the Roman pontifical authority, and Freud’s dismantling of traditional psychology were not that different from Thomas Kuhn’s arguments against the domination of logical empiricism over science’s supposed unilinear development. All three perspectives resisted conventions, structures and principles—but each was also hermeneutic, because each presupposed the right to interpret differently the conservative norms of descriptive philosophies.

Intellectuals like Philip seem only interested in describing the world–but perhaps our crisis is now great enough that even he will have to eventually consider interpreting it.

Jim says:

I’m not willing to go the distance with Rorty or Vattimo and Zabala and say that all knowledge is socially constructed, but I certainly agree that a great deal of knowledge is socially constructed. Take “rationalism” for instance, or what Phil calls a “rational doctrine.” Now just what people imagine by that I do not know. But if you look what happened in ancient Greece, it was a piece of metaphysics used to justify slavery. And that’s pretty much been the history of rationalism right down through the ages. That’s why Marx blew off animal rationale and replaced her with animal laborans. As Hannah Arendt noted: “Before Marx only Hobbes…had felt the necessity of finding a new defintion of man under the assumption of universal equality.”

But I think there’s evidence of the kind of thing you mention a lot closer to home than Galileo. Robert L. Heilbroner in The Worldly Philosophers says of The General Theory that

So this begs the question: Was The General Theory nothing more than putting a “scientific” veneer over policies that had already been dictated by political exigencies?

This is most germane now because of something Roger Farmer said:

But isn’t what Farmer is suggesting to be done what FDR did? Here’s how Frederic Lewis Allen explains it in Since Yesterday:

So exactly what was Keynesian spending? As Allen explains, the government was

Two more points. First, just because Keynesian spending may have originally come about due to political exigencies, or by random chance, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. A lot of scientific discoveries are made by serendepity. Second, the other day you said that Vattimo and Zabala argue “that only the strong determine the truth because they are the only ones who have the tools to know, practice and impose it.” That’s structuralism with a Marxist spin: the structure is merely the instrument of privileged classes. That’s an unbelievably pessimistic world view, one which I would counter with this from Jonathan Schell:

One thing that should matter in economics is expectations about the future. These expectations are built from selecting a bunch of sources/prognosticators. So, false rumours matter, and so do overconfident positive or negative outlooks. In a Gold Rush, even fast food sellers can make a lot of money, because the most lucrative business is panning or mining for gold. As the Gold Rush abates, one is left with a few ghost towns. Of particular interest these days is consumer confidence, ISTM.

William C says:

January 28, 2013 at 9:25 am

“An alternative approach of course is to suggest that we need better religion in economics. I think Catholic Social Teaching, which calls for social justice,has something to offer contemporary society.”

What disappoints me is the lack of good analytical economics in Catholic Social Teaching and any sense of urgency to get it.

I wanted to add two more thoughst to this important topic, where and whether religion and economics cross and merge.

First, I believe one of the best ways to measure whether economic orthodoxy has crossed over into the intensity of religious values (and functions)is to consider heretics and their treatment. Of the two important books on economics written in 1944, Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom” is the one on most lips, most common currency, while even within the economics profession itself one crosses into heresy indeed to mention the other “great” book from that year: Karl Polanyi’s “The Great Transformation” which had, near the center of its heresies the view that idea of a pure free market produced such intolerable human conditions (and early warning, conditions for nature) that no parts of the political spectrum could live with the results and that much of the tactical strategies of politics in the 19th century can be seen as the attempt by the left to cross the theological lines drawn against intervention into various markets by governmental action, and the inability of even the market champions to live with the status quo: hence the development of central banks to distribute the pain of deleveraging after panics, collapses, on a less painful and more equitable way for the major players. Now Polanyi’s has some memorable and powerful denouncements of the pure free market, but much of his coverage of the 19th century skirmishes over policy is subtle and nouanced – but to no avail…how many years can you follow the news at Bloomberg and not seem him mentioned…while Hayek pops up regularly.

Today, thinking of what we have all been through since 2008, Krugman’s lamentations of the suffering – unecessary – of those still out of the labor markets – and his further lamentations about breaking the old consensus within the profession – you have to agree that one of the brightest, if not the most powerful uncrossable theological/ideological lines is that posed by governmental intervention into the labor markets. I believe that this is the theological force field which keeps Ben Bernanke corralled within his complex monetary operations; after all, being a student of the Great Depression, admittedly focused on the maneuvers of the Federal Reserve then, and what they did wrong, surely, nonetheless, he is aware of FDR’s New Deal interventions into the labor markets via the WPA and the CCC…but he simply cannot openly discuss them; the questions is open as to what he believes about public job creation…whatever his internals on that, publicly, significant portions of our own economic history have been erased, never to cross his lips.

Today, such ideas are heretical not just here but in Europe;just follow the prescriptions for more “fluid and flexible” labor markets, meaning longer hours, less pay and fewer defined protections – more power, in short to the employer’s market power.

If there is a brighter “no crossing” line for the Democratic Party as well, I’m unaware of it. According to my contacts within the Kansas City School, just to show you the rigidity that this policy area is policed with, the proposal for full employment, guaranteed employment, worked on by Randall Wray, M. Auerback and others, at both a theoretical level, was rejected, flatly, even by the AFL-CIO when they approached them for support. No wonder James Galbraith fell back to the still laudable 12-14 $ per hour minimum wage proposal, having run into the same theological force field on job creation proposals as the Kansas City folks. I still remember the panel debate, in early 2010 in NY City when Nial Ferguson jumped, with a great deal of passion on all the Keynesian heads then rearing up, and declared, much as the Republican Right does, that “only the private sector can create value” …jobs and so on..the whole chain of positive events in an economy.

I’ll close with a personal instance of when I encountered such a theolgoical bright line in economics. From 2005-2010 I was a regular attendee at many think tank productions/panels – usually economic ones, and I have to remark that inside the Beltway shows are remarkable for their lack of passion, displays of anger and so forth…it is like everyone is tightly bound by hidden force fields on the topics of the day…and their world be dire and immediate consequences if they crossed them in public…since these presentations tended to be from centrist or slightly liberal institutions (Center for American Progress, Brookings…EPI), it is clear that the conventions are widespread…I had started a conversation with someone who worked for the Center For American Progress, who had been hired away for his military and foreign policy background, in my take, to make the left look tougher on those issues, and while I do forget the exact topic of the panel that day, it was such that I gave him a plug for a financial transaction tax.

Well, it was like setting off an ideological land mine, what an explosion of anger, I’ve never seen such emotion from the center, because as it poured out in my direction, it seemed as though it was unravelling – that mild little transactions tax – the entire chain of economic being represented by the Washington consensus: didn’t I believe in the free flow of capital between nations, free trade…a merely incremental charge of well below one percent per transaction, was going to pull down the entire international trade system. I’ve only encountered that type of triggering mechanism a few times in my life: two before that, and they both went off with conservative parties on the other end. It’s as close as the modern thinker gets, I imagine, to what it must have felt like at the height of the religious wars in the 16th century, or, a little closer to home, the factional fights over left theology in the 1930’s, right here in the USA.

So there it is: religious intensity in a supposedly secular field, but one that stands at the very center of the modern world and its ideas about progress. Just a heads up on where the landmines are buried.

Ah, good old Polonyi. He made it sound like the “pure” free market system was ‘Satanic’ and said so in his books…..

“…a merely incremental charge of well below one percent per transaction, was going to pull down the entire international trade system.”

I doubt that, but what it would put a stop to is High Frequency Trading, and once that’s gone we’d see the true volume of transactions taking place and the lack of real liquidity that it represents. I’ve seen figures as high as 70% cited for HFT volume on the Big Board, so what happens when you take even half that amount off the table? Blue chips start trading like mining stocks is what, and who wants to see that? Frankly, HFT is a gift to anyone smart enough to see the opportunity being presented and get the hell out before the whole rotten mess collapses. Meanwhile, vested interests will do what your guy did – get angry and misdirect. They know what’s going on – they just don’t want you to know.

ebear says:

January 28, 2013 at 3:22 pm

“Dynamic Equilibrium would probably be a better term.”

Isn’t it better to drop the whole idea of equilibrium altogether or call it “Dynamic Temporary Equilibrium” or something like that. As Steve Keen points out in “Debunking Economics” that if you’re too poor to afford to buy steak and so buy sausages then if the price drops on sausages you don’t necessarily buy more sausages but buy less and buy some steak. In other words there’s never any stable homeostasis to reach because “hunting” is always going on!

The more proper term than equilibrium is disequilibrium. And the mathematics that describe systems in disequilibrium is “complex system dynamics.” It’s not all that old and is called by many “chaos theory” and is attributed to Edward Lorenz, an MIT mathematician in the early 1960’s IIRC.

The mathematics is a bit intimidating as I found out from my son last year who had an engineering course on it in grad school. It may be hairy, but it’s invaluable in dynamic engineering systems, prediction of hurricane properties/paths, and cyclical biological populations, etc, etc…

Steve Keen is developing his Minsky code for describing the interaction between measurable variables in economics. He has a wonderful discussion of the project in a recent blog post that also covers the basic history of its development. Follow his links!

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2013/01/08/tell-me-what-the-wires-do/

He is in the process of turning the words and ideas of economics by Keynes, Fisher, Schumpeter, Minsky, Godley and a host of others into a mathematical description of a complex dynamic system. There’s no equilibrium — there’s disequilibrium instead where the system properties are capable of cycling around a “stability area”. A critically important aspect of these disequilibrium systems is that some departures of variable values can result in chaotic behavior of the system — such as a catastrophic crash. Keen is going where modern engineers and atmospheric system scientists have already plowed the mathematical ground.

I think Keen’s approach is a pretty good beginning for a rational, phenomenological, empirical approach to understanding our economic systems.

Google finds many images of the Lorenz attractor. Each tangled curve shows how three related quantitities evolve over time. One way is increasing time, and the reverse direction on the curve would be decreasing time. It’s been called a case of deterministic chaos, or the butterfly effect.

Thanks for adding that. In addition, I believe that the general idea of Lorenz’s is not limited to 3 variables. With more variables it’s much harder if not impossible to “picture” it in our three-dimensional universe.

ebear says:

January 28, 2013 at 4:04 pm

‘The new paradigm is that any proposed economic ideology must now build itself upon a foundation that understands human nature is ambivalent.’

“Exactly. A variable, not a constant. I would push this notion even further and suggest that we now have the ability to change the underlying neurological substrate that governs our innate behavior, effectively tunneling through the evolutionary barrier of selection over time. Cell phones are an early example of this – a prosthetic form of telepathy that effectively mimics the real thing.”

Yep. But we can’t go into the “teleological/intentionality” thing like Teillard De Chardin and his “Noosphere” because we don’t have the evidence to prove that human consciousness doesn’t do anything more than help us better secure energy sources for survival purposes.

“Yep. But we can’t go into the “teleological/intentionality” thing like Teillard De Chardin and his “Noosphere” because we don’t have the evidence to prove that human consciousness doesn’t do anything more than help us better secure energy sources for survival purposes.”

The evidence may be lacking, but the opportunity to search for it is vastly greater today than in de Chardin’s time – or at any previous time in history – and that’s a direct outcome of improvements in securing energy sources for survival, I’d say. The fact that we’re here talking about it is sufficient evidence for me to continue the pursuit. How about you?

F. Beard says:

January 28, 2013 at 10:04 am

“The Bible forbids counterfeiting and usury from one’s fellow countrymen and especially from the poor YET our “private” money system, the banking cartel, is based on all of the above! Indeed, the poor are not charged 0% interest as the Bible commands but are charged the highest interest!

So just what religion is neo-classical economics based on?”

I guess Phillip Pilkington is really trying to claim Neo-Classical economics is pseudo-religious in its tribalistic worst.

Well, he threw in “the Religious Right.” The final authority of the Religious Right (exception Catholics?) is the Bible so it is noteworthy that the Religious Right is at odds with its own final authority. But how many Progressives know that, being ignorant of the Bible themselves?

@Beardo, the problem is that each sect chooses its – own point of origin – along a very extended time line of human history.

As many would like to BELIVE in its point of origin as – unique and unassailable – to THEIR connection with a/their creator… as opposed to all others… past, present and future…

Skippy,,, How one *believes* in such stuff – economics/religion – as a means to create_human reality_is the issue. Remember the circumcision fracas and the resulting… a vacuum can be segregated almost to infinity~

As it happens, today I was looking up “The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,” and it turns out it’s from The Merchant of Venice, Act I, Scene III, where Antonio and Shylock seal their bond.

So, usury must in the zeitgeist right now, given F. Beard’s re-appearance — and the play also concerns speculation, globalization, risk, and “I know not why I am so sad”.

All in all a very modern play indeed.

The link is dead for “As we have discussed” dealing with the simple supply and demand graph.

Neither science nor religion, economics should be in the service of one thing: what the people in a society decide they want to do for themselves.

Well it seems to me that the public interest, a difficult proposition in itself, has been turned over to, by both parties, what the most powerful private interests say is good for them – the corporations and Wall Street will find and carry out what is good for the nation economically…and there is only a tiny minority of the economists profession who would differ with summary. The fact that the balance of power in the civil society which existed just after World War II has been destroyed by the rise the Republican and Religious Right, beginning in the 1970’s and accelerating through to the present time…even to dominate the reaction to the Great Recession…shows us what trouble we are in…these have been the Utopian years of the market utopian economy…and reflected in that Time Cover of the Committee to Save the World, and the theories about the end of recessions…markets having perfect knowledge…the sum of all existing knowledge…John Grey was right to declare the danger in his “False Dawn.” Thomas Frank stated his incredulity that a financial disaster brought on by unchecked capitalism could lead to a resurgence of the Right which caused it (in his book Pity the Billionaire…) what will be the sources of a new definition of the public’s interest…where does anyone see that in the social and economic landscape spread out before us? Wendell Berry delivered a really provocative and powerful critique of the economy from his unusual perspective as a Kentucky farmer…miles and miles of separation from him and the economics profession…yet the essence of his critique of capitalsim in his April Jefferson Lecture…was very close to Krugman’s “Robots and Robber Barons” column from a few weeks ago…of course Krugman didn’t reference him…Berry said the nature of our economy is now devouring the society, a very powerful way of expressing that conventional economics, which supports the main directions of creative destruction and the “inhuman pace of technological change” that economists are so in love with (and no small part of the society itself)is no place to turn if you want to alter course. The people in this society, it seems to me, are servants of the broader economic currents, not the economists or their economy the servants of the public good…the left “opposition” today is so fragmented into submovements, and the weakest of all of them seems to be those who chief focus is on the political economy…

It always was a major revelation point to me that most certain voices for the economic Right in Congress, including the major business lobbying groups, claimed the absolute monoply of job and value creation, and relished the idea that their liberty and freedom meant that even they did not know what the next best thing – or direction was going to be…if you are happy that in the field of energy production, its domestic gas via fracking, that’s your public interests gift from the market (driven by taxpayer and academic supported research).

F. Beard says:

January 28, 2013

“Well, he threw in “the Religious Right.” The final authority of the Religious Right (exception Catholics?) is the Bible so it is noteworthy that the Religious Right is at odds with its own final authority. But how many Progressives know that, being ignorant of the Bible themselves?”

Well so what’s new about about a religious movement, not just the Religious Right, being at odds with the bible on usury? Read the historian R. H. Tawney’s book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism” where he states that whilst the Catholic Church was trying its best to uphold the Bible’s teaching on usury its Popes were borrowing large sums of money from money lenders repayable with interest. The reason? Because it was very difficult for the church to ultimately have moral influence without getting tangled up with politics and as Mao-Tse-tung was fond of saying “Power grows out of the barrel of a gun!” although to my mind he ought to have added “and a barrel of money!”

Yes, you are right about the problems of the medieval church and politics. Another aspect of the problem was that even if the church had wanted to stay out of politics, the politicians (kings, emperors) would have given it little choice, appointing popes, bishops wherever they could. So the Papacy set itself up as a political power to try to free itself from the Emperors. But that created a whole new set of problems. There are interesting parallels now with the Chinese authorities and the Dalai Llama’s succession.

somehow I think we need to re-write “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” so that it deifies the god of the unrestrained free market in song. Every religion needs a hymn.

I tried to get some lines down tonight but, unlike Julia Ward Howe there in the morning with her dream only half shaken from her head with pen in hand at the Willard Hotel, after reviewing the Union troops at Upton Hill in Arlington the previous day, there where I have stood among the trees, on that very ground outside of Washington, DC, right where she stood, underneath the living sky in the cold blue of the afternoon, on that very same sacred ground, I sadly didn’t have much luck. Her version is immeasurably better in every way. This may take some time

something like:

mine eyes have seen the glory of the growing of my hoard

it hath trampled down the vineyards where the fruits of work are stored

it hath sliced the throat of justice with its terrible swift sword

its truth is marching on

glory glory how I’ll screw ya

glory glory how I’ll screw ya

glory glory how I’ll screw ya

its truth is marching on

da-da-da-daaaaa

There’s about 5 more verses.

Maybe if an equilibrium state can be reached, it will flow effortlessly. But in reality, I think usually it has to be there, already formed, and it just surges out and you just watch it and write it down. There really isn’t an equilibrium there any more than on the toilet taking a crap. It’s there and it just needs to come out. Things are like that, mostly. Even the idea of equilibrium is like that. Like a piece of mind shit that came out because the faculties weren’t subtle enough to see it for what it is.

If there is no homeostasis because the market is always “hunting” this tends to fit in with Godley’s analysis that there are always flows flowing and stocks temporizing.

I read Nelson’s book a couple of years ago, and thought at the beginning that he was on the right track. But as it went on, he was doing a he-said she said. More to the point, he did not do what I expected, which wa to compare economics as currently practiced in graduate instruction with systematic theology. Since I know something of both, I can confirm that economics is very much like systematic theology. The Pareto criterion is pretty close to the ontological proof of the existence of God. A serious book on this subject (for those with the patience and ability to understand it) would be a great contribution to our intellectual life. Nelson made a start, but did not have the erudition nor the ability to carry it through.

Phillip,

Classical economics is founded in the wave of intellectual developments after classical or Newtonian physics. The economy is seen as a mechanism which works according to regular principles which can be determined. Physics has moved on, but so has economics. But not as well in its larger scale form of political economy. Until Keynes, of course. And it should come as no surprise, that Keynes modeled his theory on the new master concepts of relativity. Here is an essay by James Galbraith that touches on all of this. The following is an excerpt.

“One of the most intriguing and little-noted facts about John Maynard Keynes’s masterwork, The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money, concerns the first three words of its title. These are evidently cribbed from Albert Einstein.* Alone that would be only a curiosum; but there is more. The parallels between Keynes’s economics and Einstein’s relativity theory are deep enough, and evidently intentional enough, to provide a useful framework for thinking about what Keynes meant to do with his scientific revolution. ”

http://prospect.org/article/keynes-einstein-and-scientific-revolution

It seems to me that there is a definate correlation between the religious right and market worship. The fascination with austerity as the answer to all our economic problems is one clue. We sinners abandoned the commandments of Market, so we must be punished by austerity. We sinned by not being rich.

Those who formulate and advocate economic policies are rarely the ones exerting control over the components; more often their role is merely to justify (sell) them to the public, much like priests carrying out edicts from the church nobles. Innovation comes about once in a great while, as reformers observe the terrible consequences of bad policy and strive to right the wrongs for the common good. Rationality (science) can also dispel misconceptions born of religious fear (the Plague). Usually, these corrections are made in the disastrous aftermath of conflagrations in which masses of humanity cry out for change and the most talented individuals step forward to rescue them.

I think humanity is again arriving at a time of conflagration, manifest in the extreme effects of climate change which are the result of entrenched economic policies perpetuated by the “nobles” of business and finance. Sadly, any reform of these will only come about as a reaction to the destruction of so much of the world’s life and life-sustaining elements, that it will be too late to rescue that which is most beautiful.