By Thomas Adams, a structured credit expert and attorney at Paykin, Krieg & Adams

A big puzzle, as oil prices have plunged and look unlikely to return to their former levels, is who is holding energy-related debt, particularly give the high level of issuance in 2014. Yet it is troublingly difficult to get hard information, a situation troublingly similar to the mortgage backed securities and CDO markets in 2008.

One issue under discussion is the energy debt concentration in CLOs. That has come into focus due to the amounts on bank balance sheets (numerous reports on Twitter indicate that the market froze last July) and that one of the provisions of Dodd-Frank gutting HR 37 that is now moving through Congress is to delay for two years a stipulation that would banks to sell most collateralized loan obligations held on their balance sheets. The reason for wanting CLOs out of banks is that they are actively traded vehicles, effectively mini hedge funds.

The reason for concern is the recent plunge in energy-related debt prices and their questionable prospects, and where that debt is sitting.

When the subprime mortgage market shut down, banks wound up eating a lot of their cooking. If that has happened again, it could show up not only in CLOs but in other assets and exposures. And if not the banks, then who were the bagholders?

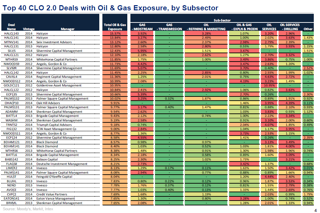

This chart shows energy debt concentrations in top 40 CLOs. The maximum concentration is 15%, presumably set by section concentration limits.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t provide the dollar amount of those deals so we can’t determine what the dollar amount of that energy related exposure is.

And this is from a discussion of a recent JP Morgan investor call:

High yield energy new issuance has doubled since 2008. It constitutes 16-20% of new issuance since 2011.

JP Morgan’s projected default rates for US high yield energy: at $65 oil, 3.9% in 2015 and 20.5% in 2016. At $75 oil, 3.9% and 4.8%.

Those forecasts look to be in need of updating to show what would happen if oil prices remain at their current $50 (and below) level.

Total leveraged loan issuance was $530 billion in 2014 and $606 billion in 2013 (two year total $1.136 billion). If energy made of 16-20% of 2013/2014 issuance, via above info, that would be roughly $182 to $227 billion (16-20% of $1.,136 billion).

Total US CLO issuance in 2014 was about $120 billion (the most ever) and about $85 billion in 2013. If energy debt didn’t exceed 15% of the CLOs issued in those years, that means CLOs bought less than $31 billion of energy debt, vs. around $200 billion of total energy debt issued.

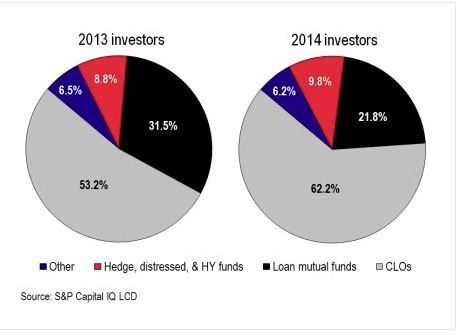

Mutual funds had been big buyers of leveraged loans, but were net sellers by the second half of 2014. So who was buying all of those energy related leveraged loans – about $170 billion worth?

According to LeveragedLoan.com, other than CLOs and loan mutual funds, the buyers of leveraged loans were hedge funds, representing 9% of the total 2013-14 loan issuance (about $105 billion) and “other” representing about 6.4% of total 2013/14 loan issuance (about $72 billion). So, if hedge funds and “other” only bought energy loans, that might account for all of the energy debt left looking for a home after CLOs and mutual funds. That seems unlikely.

There may be a definitional issue. Maybe what CLOs call “energy related loans” are not what we, or leveragedloan.com or the bank analysts would call “energy related”?

Remember, there was a lot time spent during the crisis trying to define what was subprime vs. Alt A vs. prime? Then during financial crisis litigation, the various bank defendants just redefined all of those terms again, to deny responsibility.

Another possibility is that a lot of the loans never actually got sold to investors – and ended up staying on bank balance sheets.

Investors are asking a lot of questions and are worried. That’s why the banks are parcelling out pieces of information. It’s troubling that this sort of thing can’t be answered easily. It’s troubling that this sort of thing can’t be answered easily.

the 2nd graphic is unreadable and apparently unlinked to a larger view..

S&P looked at 700 CLO’s and said energy expsoure was ~3%.

http://www.structuredfinancenews.com/news/cdo/clos-have-relatively-low-exposure-to-oil-253923-1.html

“Based on a review of about 700 U.S. CLO’s rated by S&P, the average exposure to energy

companies is only about 3.3%; that’s a much lower concentration than these companies have in

overall junk bond and leveraged loan markets, at 17%.”

It’s not relevant data. We discussed this issue before. That data covers a much longer time frame, when energy debt issuance was much lower than now. What we need is 2013 and 2014 data carved out, and particularly second half 2014, which is what the banks are likely carrying on their balance sheets.

Moreover, this does not address the other issue Tom Adams raised, that the structurers are almost certain to have finessed the definition of what is “energy debt” for the purpose of the CLO diversification models.

Finally, I have not seen the report proper, but if these deals were static CLOs (as in assets could not be traded once the deal was set up), it’s not a relevant data set. The banks own “managed” CLOs, where the assets are traded in and out.

As we wrote in comments to an older post:

Finally, the the 3.5% concentration figure is often bandied about. That is for the aggregate CLO market or the top 25 issuers, depending on the source. That is another obvious deflection. Who cares what was issued in 2007 or what those deals hold? It’s just like the arguments made back in 2007 that subprime was only 15% of the aggregate mortgage market – completely and deliberately obscured the issue. What is germane is what the energy concentrations are for the 2013 and 2014 deals, and most important of all, the ones that banks are holding now that the music has stopped. I suspect many are at their maximum concentrations for energy and others have gamed the concentration limits. In addition, the odds are high that there is major adverse selection for the ones that are on bank balance sheets – the deals for which there was weak investor demand are they ones with higher energy concentrations and they ended up at the banks. The fact that Citi has been pushing for this [the delay in the Dodd Frank requirement to sell CLOs] is a pretty good indicator. Citi was the 2nd largest underwriter of ABS CDOs but they never actually sold a single bond: all of those deals ended up on Citi’s balance sheet, either directly or through off-balance sheet vehicles. This happens repeatedly in the securitization market – easy to get to the top of the league tables if you don’t have to sell to third parties, see GE/Kidder in the 1990s. Since there was basically no punishment for that last time, it’s reasonable to be concerned that it could be happening again, particularly in light of how aggressive the bank lobbying has been.

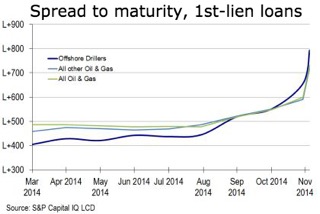

Re first chart.

Lol oil drillers have their own hockey stick of doom

A big puzzle, . . . who is holding energy-related debt?

. . . banks wound up eating a lot of their cooking.

I hope they get food poisoning and it kills them, otherwise we end up eating their cooking.

Thank goodness there’s no FNMA for oil debt.

It’s going to take a little more doing for the banks to figure out how to stick the rest of us with this one.

I’ve been pondering this for the past few weeks. Ya’ll posted something about the deepening leverage in these new industries last year, and it’s stuck with me ever since.

The rent has to come due at some point, particularly if these prices stay as low as they are for another quarter.

What ??

Regulatory forebearance………..again ?!?

But, but,….we were doing so well allocating resources such that the system runs smoothly on it’s infinite expansion path…

Don’t the banks already have that covered with several billion worth of derivatives just in case the price of oil doesn’t recover in time? And the depositories of all the big banks are stuffed full with these contracts so the banks are covered either way? Is there a regulation that forces the banks to account for the derivatives or are the details being kept secret? Another question is why on earth the banks did all this gambling with oil, a commodity, when it is clearly against federal, and Fed, regulations. So technically the Fed cannot bail them out. Right? So either the Fed is complicit or the banks are completely ungovernable.

A ton of money was invested ramping up oil production, in the US by up to 75 percent and at least 5 percent by OPEC. Now that the price of oil has collapsed, who is left holding the bag, and who gained from the collapse? We don’t know the answer to either question, and the fact we don’t know demonstrates the opacity of the actions of financial players in today’s environment. I’m not inspired with confidence. One observation is that when stimulus was the ostensive objective, the response by whom was to pour money into oil speculation and production as a preference over other possible investments.

Remember what happened in the 2008 crash: each bank thought the other guy was holding the bag. Turned out they were holding the bag for each other and they were all bust.

They’re still all bankrupt.

Obfuscation and lack of timely and accurate reporting of information about developments that could potentially impact the economic health of the nation and jeopardize the status quo is premeditated and attributable in large part to the success of the large Wall Street banks and their fellow travelers in peddling their “Deregulate!” meme. As Yves noted above, deflection is again also playing a big role.

It’s a well-worn playbook:

… “Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage.” —MIT Economics professor Jonathan Gruber

… “Perception is reality.” —Lee Atwater

Maybe they can again just move these “assets” from the “Mark-to-Market” bucket to the “Mark-to-Model” bucket for accounting purposes (If they’re not already so categorized). After all it’s Liquidity that kills, and that’s why we have the Fed… isn’t it?

I can see that it is in the interests of those holding these CLOs to hide these potentially toxic assets and to keep them from wrecking the holder’s balance sheet. That is pretty obvious.

But I do not understand s how large (and how toxic) these assets are relative to the bad financial products created during the real estate bubble. And how much risk this presents to the financial system. For example, will there be defaults?

I have read a number of analysts who say that the capital that has flowed into energy is a financial bubble that is going to burst and create a a lot of damage. What are the chances of that actually happening?

We’ve discussed this in the past, but I appreciate that not everyone has the time and interest to follow this topic consistently.

Basically, CLOs do not have the structural defects that led them to fail catastrophically like subprime-related CDOs. Even if there are losses, they will not be as severe.

But the general question is more important. Where did the energy debt go? How much is on bank balance sheets, directly or indirectly (as in in the form of derivatives, not just cash market exposures).

Thanks Yves — I appreciate the response. I’ll work harder to stay caught up in the future, :-)

I am new, but I can see that I am going to be spending more time here. Thanks again.

They are quite fictitious securities. Why anyone regards them as real is beyond me. When they are in the money, they are quite real. When they are horribly underwater, off to the Fed garbage can they go. It’s only paper and make believe. Hello.

I suspect a lot of that debt is sitting in Business Development Company (BDC) funds. One of the consequences of the Volcker rule limitation on PE was an explosive growth in BDCs, which are one of the Volcker permissible alternatives for the banks. These are a natural home for high risk investments.

I need to dig a little deeper to determine the size of BDC relative to the market, and to determine if they are already counted in the ‘other’ category in the analysis you cited in your piece.

http://bdcbuzz.blogspot.com/

It has become obvious that low oil prices are going to be a topic of discussion for BDCs with larger amounts of oil/energy related exposure. This includes portfolio companies and other investments such as CLOs. I do not consider BDCs as an investment only in the financial sector and one of the reasons that I prefer them to other higher yield investments is because they invest in multiple industries. Currently the average BDC has around 6% to 7% of the portfolio invested in oil and energy related companies but this ranges from none to almost 20% for certain BDCs

Fitch was raising warnings about the sector in Nov

http://blogs.barrons.com/incomeinvesting/2014/11/10/trouble-ahead-for-high-yielding-bdc-sector-fitch/?mod=BOLBlog

A related quesion would be who are the counterparties to the oil hedges? I keep reading about the oil producers hedging a part of their future production at huge levels compared with the spot prices. Who’s taking these colossal losses?

For example, I read that Mexico hedged their entire 2015 oil production of 228 mb in Novermber 2014 for the price of $75/b with seven “international financial institutions”. If we multiply the volume by $30 (75 hedged – 45 spot) = approx $9 billion/year. Who are these financial institutions? How do they survive?

Yeah, yeah. This is the beauty of credit money supply control and futures markets price manipulation. There will be a lot of sell offs of drilling companies who hit real wells to Big Oil & Gas. As expected. This is how wealth is concentrated for 500 years of this money system, the owners of which are also the real controlling stake owners of Big Oil & Gas. Nothing new here. Only chumps were unsuspecting.

I would have readers look under the hood of public pension portfolios.

The politicians who authorize contributions to DB public pension plans face three choices to address under-funding: 1)raise taxes, 2)cut spending, or 3)reach for yield. Since the first two result in political death, plans have gravitated toward the third option. Public (as well as private) plans have been loading up on high yield debt – much of which is used to satisfy the intense capital needs of energy extraction firms. While the attributes of high yield (fatter coupons, exposure to domestic job-producing industries, getting paid for illiquidity) all make sense for long-term savers (or pension plans) my concern is that too few have connected the dots to see how the crash in oil prices will impact their portfolios. Firms shut down operations when marginal costs exceed marginal revenue and the decline in oil prices will drive many domestic firms to pull the switch. That leaves new capital investments without any revenue (and limited salvage value). Bankruptcies will follow.

Unlike the sub-prime crises the rating agencies have done a better job in this cycle rating some of the energy debt as “Junk” (B/CCC) either on weak fundamentals or increasing lite covenants.

Again, unlike the sub-prime crises where owners of AAA borrowed heavily (and therefore were forced to sell when prices dipped) public funds can a) hold high yield without selling, and b) can amortize losses over many years.

Like the sub-prime crises we have a situation where personal incentives (making option 3 the only choice, and ignoring 1 and 2) drove institutional decision making to the determent of the overall economy.

Since public funds meet infrequently, awareness of the damage may be delayed, and hopefully spread out across a diversified portfolio to include stocks (that have risen). That said,to achieve the 7-8% targeted returns (and to address rampant under-funding) plans need to be hitting on all cylinders.

Net, the drop in oil prices will hit pension plans, but they will sweep the problem under the rug (as they won’t have to address the problem immediately). Whether good news or bad news, that probably means that plans will go on investing in “story” products praying that option 3 (higher yields) will bail the sponsoring governments out of the political mess they created for themselves.

Yeah, it’s pretty clear the bankers are looting the pension funds. Pension funds are on the bad side of a lot of trades.

But I think the other thing going on is that each bank is selling junk to the *other banks*. So all the banks are on the bad side of the trades as well as the good side… it should crash just like it did in 2008. They haven’t learned anything about fragility of interconnectedness.