By Eric Tymoigne. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives

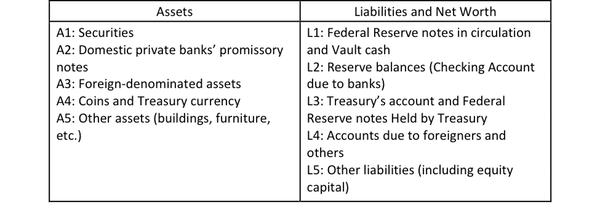

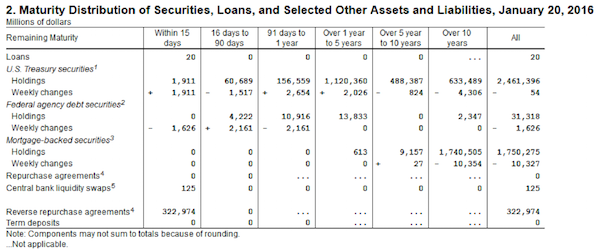

For convenience, I have put the balance sheet of the Fed below. A previous post examined the balance sheet and another one provided important information about the meaning of reserves and other basic concepts and their relation to the balance sheet of the Fed. Now let’s look at monetary-policy implementation.

What Does the Fed do in Terms of Monetary Policy and Why?

While details in operating procedures have changed through time, the Federal Funds rate (FFR) has progressively gained in importance as a relevant operating tool (i.e. means to implement monetary policy) since the 1920s. The FFR is the rate at which participants in the Fed Funds market lend and borrow Fed Funds to each other for one day (overnight).

Fed Funds are the dollar value of the Fed accounts (L2, L3, L4). Holders of these accounts include private banks, Treasury, GSEs, IMF, securities firms, among others. Some of these account holders need more funds (usually banks) while others usually have more than needed. The Fed Funds market allows these participants to meet and make deals.

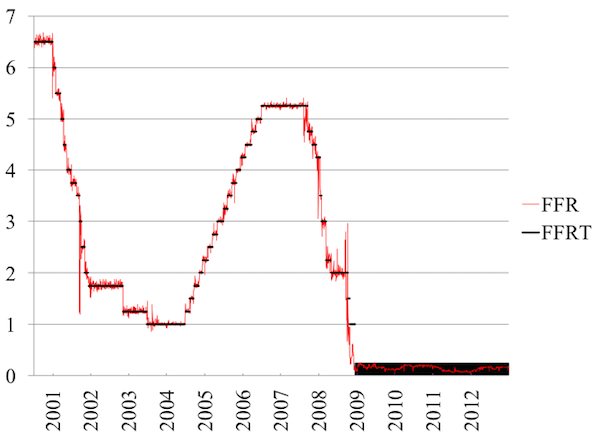

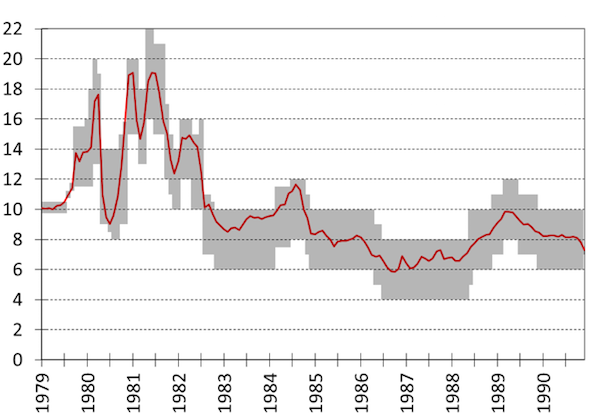

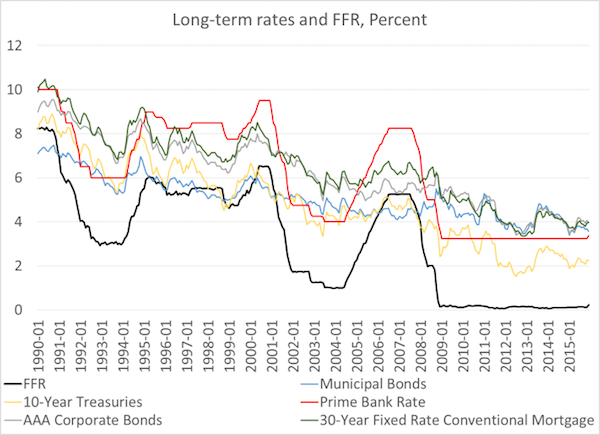

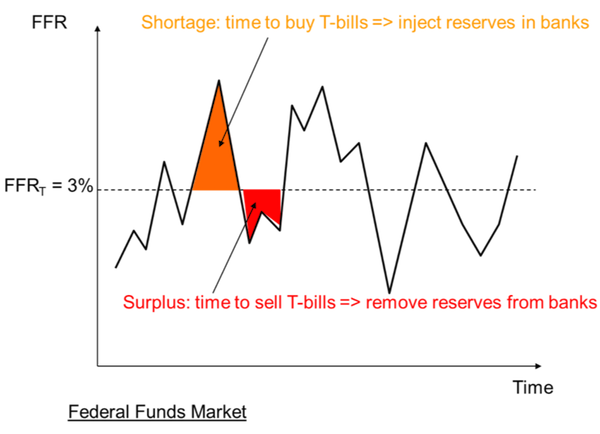

The Fed is highly interested in the FFR and aims at targeting that rate, i.e. the Fed wants to make sure that the FFR (that is market determined) does not deviate too much from the FFR desired by the Fed (the FFR Target) (Figure 1). Most of the time the Fed targets a specific number but sometimes it targets a range. This is the case today with a range of 0.25-0.5%. From the late 1970s until 1991, the Fed also had a range that was as high as 16%-22% in mid-1981 and as wide as 13%-20% in early 1980 (Figures 2). Since 1994, the FFR target has been public information as the Fed committed to become more transparent.

Figure 1a. Daily average of FFR and Target FFR, Percent

Figure 1b. Monthly FFR Average and Target FFR range, 1979-1990, Percent

Source: Transcripts of the FOMC meetings

Note: After 1990, the FOMC targeted a FFR digit

The Fed is highly interested in this interest rate for two main reasons. First, the FFR is a cost for banks so if the cost changes, the interest rates they charge to customers will change. Second, market participants make portfolio choices (i.e. buy assets) with the aim of maximizing rate of return. They will compare portfolio strategies and choose the one that provide the highest return. While making these portfolio choices, financial-market participants take into account future monetary policy (i.e. future FFRT), which hands up affecting interest rates on a wide range of securities.

Regarding the cost side of FFR, banks need reserves for four purposes:

- Withdrawal by customers: people get cash from the ATM

- Meet reserve requirements: banks must keep a certain amount of reserves that is a proportion of the bank accounts they issued

- Interbank settlements: paying debts due to other banks

- Make payments to other Fed account holders: for example tax payments leads to a drainage of reserves

By far, the largest day-to-day need is interbank settlements so a bank that doesn’t have enough reserves to meet payments must get reserves to avoid default. A bank may then either get them from other banks or other Fed Funds holders, or may go to the Fed. In any case, the bank will have to pay interest, the FFR is what banks pay to get reserves through the Fed Funds market (“non-borrowed reserves”). This cost is then passed to their customers so when the FFR rises, rates on mortgages, advances to students, credit cards, etc. also go up (see prime bank rate in Figure 3).

In terms of portfolio choices, say that in 2016 you have $1000 and you want to figure out a way to make the highest gains over the next two years. Say only two portfolio strategies are available. A “long-term strategy” is buying a 2-year security that pays 5% and keeping it for two years. A “short-term strategy” is buying a 1-year security that pays 3% and reinvesting the proceeds in 2017 into another 1-year security. Your choice between the two strategies should depend on what you expect the 1-year rate to be in 2017. You will be indifferent between the two strategies if they provide the same rate of return, which means that you expect the 1-year of about 7% in 2017 (solve $1000*(1.05)2 = $1000*1.03*(1+x) where x is the expected one-year rate in 2017). If you expect the 1-year rate to be higher than 7%, then the short-term strategy is more profitable. In that case, financial-market participants will sell outstanding 2-year securities and buy 1-year securities, which end up raising the 2-year rate until the two strategies provide the same rate of return. Generalizing the logic, a rising FFR (similar to 1-year rate going up) raises the rates on longer-term securities. Long-term rates depend on expectations about future monetary policy and if FFR is expected to rise (fall), long-term rates will rise (fall).

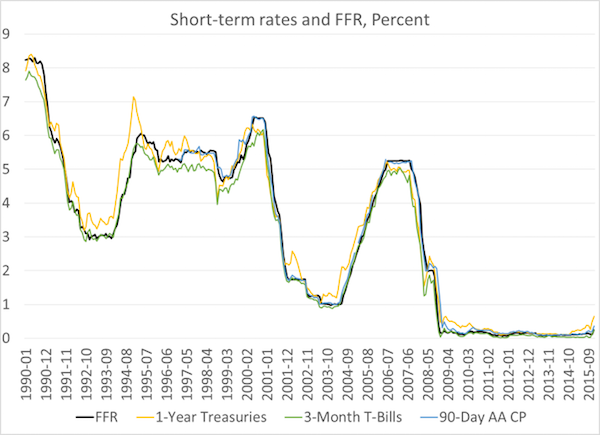

There is a very high correlation between the FFR and all other interest rates. The correlation is about 0.99 for short-term securities and about 0.8 for long-term securities like T-bonds (Figure 3). Beyond expectations about future FFR, the interest rate on securities, especially of longer term to maturity, is also influenced by inflation risk, tax risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, among others, which makes the link between FFR and longer-term securities less strong.

Figure 3a. FFR and other rates

Figure 3. FFR and other rates

By influencing interest rates, the Fed hopes to influence the willingness of the private sector to spend on goods and services; the ultimate goal being to influence inflation and employment. For example, if the Fed thinks that inflationary pressures are building up, the reasoning goes at follows: Higher expected inflation by Fed leads to higher FFR target, which raises the FFR, which raises other rates, which discourages private indebtedness and raises thriftiness, which slows down spending on goods and services, which slows down inflation. There are a lot of steps between FFR and inflation/employment, and one may doubt it works well, but that is the logic behind the intervention of the Fed in the Fed funds market.

The Fed has a dual mandate, i.e. its goal is to achieve both price stability (currently defined unofficially as achieving a 2% inflation rate) and full employment (defined as being at an unemployment rate at which inflation is stable, the “NAIRU”). Other central banks, like the European Central Bank, only focus on price stability.

Targeting the FFR Prior to the Crisis

While banks do need reserves, they also do not like to hold more reserves than they need because reserves don’t pay any interest. As we saw in the previous blog, prior to the crisis, banks held very little reserves overall, and most of them were held because the Fed required it. Banks like to keep a bit of excess reserves to avoid the overnight-overdraft penalty rate (recall that L2 can be negative).

What happens if banks cannot get enough Fed funds? Banks can’t create more than what is available, only the Fed can. If the Fed does not add more Fed funds then the FFR will rise steeply and quickly given that bank must have the reserves they need (a higher FFR does not remove the incentive to borrow reserves).

What happens if banks have too many Fed funds? Banks can’t destroy/remove Fed funds, only the Fed can. If the Fed does not remove Fed funds, the FFR will fall very quickly to 0% given that banks don’t have anything else to do with the excess reserve balances they have (a lower FFR does not give incentive to supply less Fed funds).

To minimize fluctuations in the FFR and keep it around the target, the Fed intervenes to add or remove Fed Funds by adding or removing reserve balances according to the needs of banks. If the FFR is above target then the Fed adds reserves, if the FFR is below target the Fed removes reserve balances.

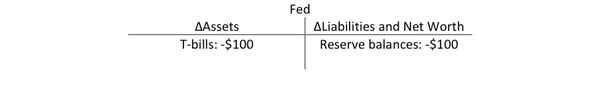

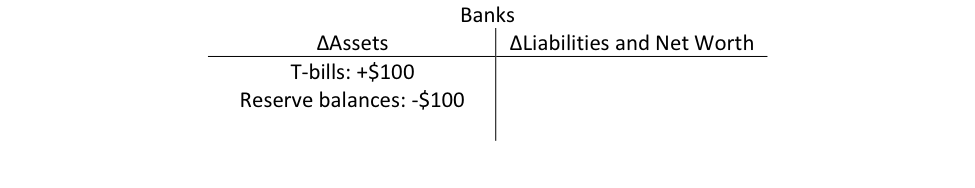

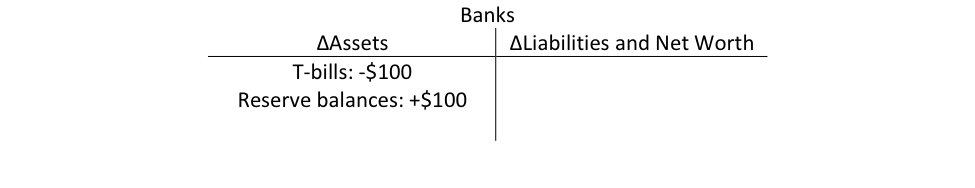

The way the Fed does this is by trading T-bills with banks (See Figure 4):

- If FFR < FFRT, banks lend and borrow at a too low interest rate relative to what the Fed wants. To correct that the Fed sells T-Bills to banks, which drains reserves.

- If FFR > FFRT, banks lend and borrow at a too high interest rate relative to what the Fed wants. Banks have too few reserves. To correct that the Fed buys T-bills from banks by crediting their reserve balances.

Of course for banks to agree to trade with the Fed instead of putting reserves in the market—or for banks to get reserves from the Fed instead of borrowing from other banks—the Fed has to provide incentives. The Fed also has to make trades that ensure that the FFR stays around its target.

Let’s see how that works with a simplistic example. Suppose that a bank has $1000 worth of reserves that it is ready to supply in the Fed Funds market. Suppose that the FFR is currently at 3%, where the Fed wants it to be, but if the bank supplies the funds the FFR will fall to 2%. How can the Fed entice the bank not to dump the funds in the market? The Fed may sell to the bank a T-bill for $997. If the bank holds it to maturity, it will earn a 3% rate of return (U.S. Treasury will repay $1000 at maturity).

The Fed would do something similar when banks borrow Fed funds at a rate higher than what the Fed wants (FFR > FFRT). It buys the T-bills at a price consistent with FFRT. That forces those willing to lend Fed Funds to comply with the FFRT, otherwise no bank will borrow from them given that the Fed offer to provide reserves at a lower rate.

Figure 4.

The Fed could do this all day long and FFR would be on target all the time, but practically the Fed only intervenes once a day and is ok with the FFR fluctuating around the target. Each day, the Fed anticipates the approximate need for reserves by estimating how the items that change the monetary base will change during the day (A1 through A5, L3, L4, and L5).

The Fed is basically applying a sort of buffer-stock policy on reserves in the same way diamond cartels limit the supply of diamond supply to control diamond price (I am sorry to tell you that diamonds are not rare). The main difference between the Fed and diamond cartels is that the Fed has complete pricing power because it is the monopoly supplier of reserves.

Beyond day-to-day intervention in the Fed funds market to maintain a FFRT, the Fed also sometimes changes its FFRT. Given that the demand for reserves is almost perfectly inelastic and given how small the increments and decrements in FFR target are (usually 0.25% at a time), when the Fed changes its FFR target, it usually does not do anything for the target to be reached. If the Fed decides to lower the FFR target, it does not have to inject reserves first for the target to be reached. If the fed decides to raise the FFR target, it does not have lower the quantity of reserves to reach the target. The FFR will move quickly around the target following the announcement of a change. This absence of a liquidity effect has been well documented.

Another way to understand that is to again go back to the point that banks can’t do much with reserve balances, so any reserves they have in excess they will supply in the market. If the Fed announces it will offer reserves at a lower FFRT, banks with reserves to lend must comply with the new FFRT when they offer to lend reserves otherwise nobody will borrow from them. If the Fed announces it will offer reserves at a higher FFRT, banks with reserves to lend raise the rate at which they will lend too. Otherwise they lose an income opportunity because banks that need to borrow have nowhere else to go (only the Fed can create more reserves and it will do it only at a higher FFR). In short: “It the Fed’s way or the highway.”

A Graphical Representation of the Fed Fund Market

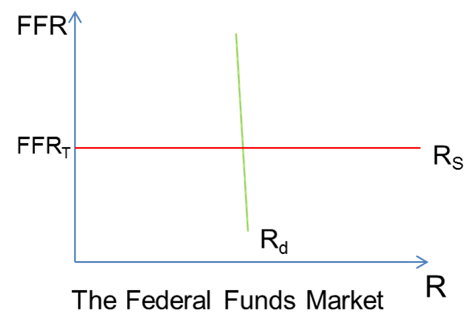

The Fed supplies, at a cost equal to the FFR target, whatever amount of reserves is needed (Figure 5). The demand for reserves is almost perfectly insensitive to changes in FFR (we will ignore complications that comes from reserves requirements, which would flatten the demand for reserves at the FFRT). Banks must meet interbank payments and tax payments regardless of what the FFR is, and banks don’t have any incentive to ask for more reserves when rates fall because banks can’t do much with them.

Figure 5

The fact that the supply of reserves is horizontal seems to suggest that the Fed supplies an infinite amount of reserves. That is not the case, all that is saying is that the Fed supplies whatever banks demand. If banks want more reserves (demand curve shifts to the right), the Fed supplies more. If banks want less reserves, the Fed removes reserves. The Fed does not proactively add or remove reserves:

- If the Fed adds reserves without consulting banks, the FFR falls to zero.

- If the Fed removes reserves without consulting banks, the FFR rises to infinity.

Thus, while the Fed does the injection and removal of reserves, the Fed adds or removes only on a defensive basis to maintain the FFR on target.

What monetary policy is all about is setting the price of reserves. The FFR is a policy variable that does not reflect any scarcity or abundance of reserves, or the preference of banks for reserves:

- A low FFR can prevail with very little reserves: if banks don’t need many reserves, the Fed does not supply many at a given FFR target

- A high FFR can prevail with a very large amount of reserves: if banks need lots, the Fed supply lots at a given FFR target.

Targeting FFR After the Great Recession

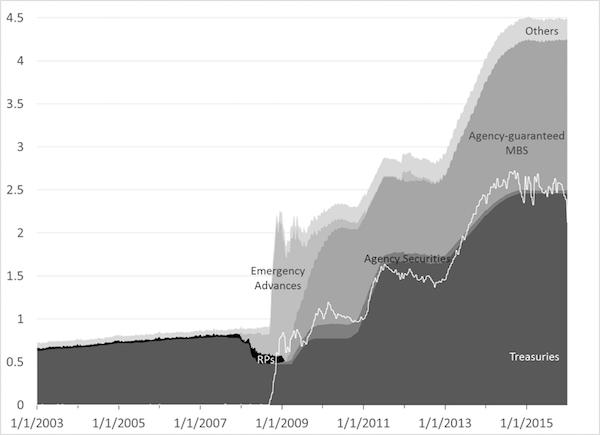

As the financial crisis grew from 2007, the Fed started to lower its interest rate from late 2007 (Figure 1) and also to provide significant emergency funds to the financial system from early 2008 (Figure 6). At first, the Fed neutralized the impact of all emergency advances by selling treasuries so its supply of treasuries fell by 40% in about six months (Figure 6). The Fed provided reserves to bank X that was in difficulty, bank X paid its creditor bank Y, bank Y had excess reserves available to lend in the Fed funds market, Fed drained all excess reserves by selling treasuries to bank Y. This allowed the Fed to maintain a positive FFR while also helping struggling financial institutions.

In September 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers disaster led to a panic and the Fed responded by providing large amounts of emergency advances (A2 went up a lot). No Fed funds market participant was willing to lend reserves to anybody; the Fed funds market froze and registered large volatility (Figure 1). Emergency advances by the Discount Window led to a very large increase in reserve balances by almost $1 trillion by early 2009. From September 2008 until the end of the year, in order to keep FFR positive, the Fed did try to neutralize some of the impact of its massive emergency operations by working with the Treasury (more on Treasury-central bank coordination later). However, in order to fight the recession (and so potential deflation and unemployment), the Fed also rapidly lowered its FFR target that reached zero (0-0.25% range to be precise) by December 2008 (Figure 1).

The Federal Open Market Committee then wondered what it could do next to help lower interest rates further. Two things were done:

- Promise not to raise the FFR target for a long time (“forward guidance”): this pushed expectations of a rise in FFR further in the future and so lowered interest rates.

- Outright purchases from banks of long-term securities with the goal of lowering long-term interest rates (“credit easing” followed by “quantitative easing”). By buying long-term securities, the Fed raised the price of these securities which lowered their yield.

The Fed bought outright long-term treasuries but also long-term private securities (MBS guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae) (Figure 6, Table 1). It did so without neutralizing the impact on reserves so reserves balances increased rapidly beyond the needs of banks. As a consequence, if the Fed had continued to operate as it did before the crisis, the FFR would have stayed stuck at 0% for as long as there would have been a large amount of excess reserves.

Figure 6. Assets of Fed and Excess Reserves (white line), Trillions of dollars

Source: Federal Reserve, Series H.4.1

Table 1.

Source: Federal Reserve, Series H.4.1

The Fed wants to be able to raise the FFR even though banks have ample amounts of excess reserves. To do so, it changed its operating procedures by paying interest on reserve balances (L2). This theoretically puts a floor on the FFR because if banks can earn interest on their Fed account, they do not have an incentive to lend these reserves in the Fed Funds market if the FFR goes below the interest rate on reserve balances (IOR).

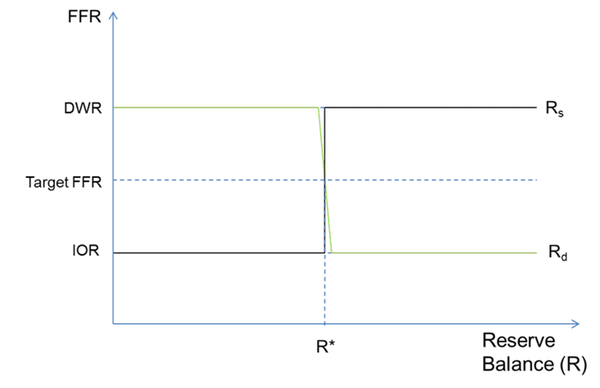

The Fed and other central banks now operate under a “corridor” framework (Figure 7). The FFR theoretically fluctuates between the IOR and the discount window rate (DWR) and all three rates move together in sync. There is a horizontal band instead of a horizontal line. Banks have no incentive to lend reserves if FFR is below IOR so FFR can’t fall below that. Banks have no incentive to borrow in the Fed funds market if the DWR is lower than FFR so FFR won’t rise above the DWR.

Figure 7. Corridor

In practice the corridor in the United States is porous. In terms of the floor, other Fed account do not qualify to receive interest on their account so they have an incentive to keep lending Fed Funds in the market even if FFR is below IOR. Government-sponsored enterprises (in L4), especially the Federal Home Loan Banks, were a major source of excess supply. In terms of the ceiling, access to the Discount Window is highly stigmatized and contains some non-monetary costs in terms of increased supervision and loss of reputation. As a consequence, banks refrain from using it even if DWR is inferior to FFR. The true ceiling in that case is the overnight-overdraft penalty rate.

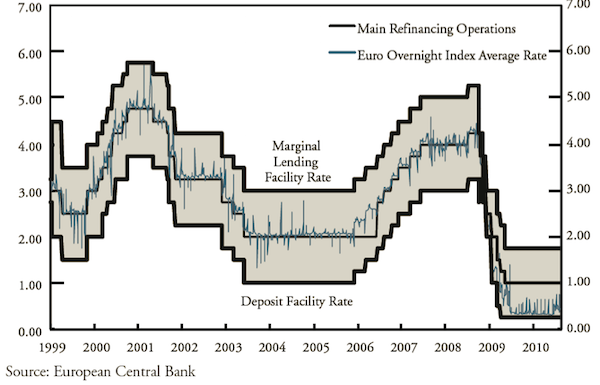

Note that a corridor policy does not have to be implemented only in period of excess reserves. If a central bank wants to intervene less frequently in the overnight market, a corridor policy can be useful to limit the volatility of the FFR. For example the ECB has been operating that way since the beginning (Figure 8). It intervenes in the market only once a week and let the ceiling and floor do the job of containing the overnight rate around the target overnight rate during the rest of the week. Narrowing the gap between the floor and the ceiling would reduce the volatility of the overnight rate. The Fed had been on a semi-corridor since 2003 when the Fed decided to raise DWR above the FFRT and to move both in sync while IOR stayed at zero all the time.

Figure 8. Corridor of ECB

Source: Kahn’s Monetary Policy under a Corridor Operating Framework

Done for today! Next blog will answer a few FAQs about monetary policy.

Agreed.

It’s interesting seeing this perspective get some attention in the context of some of the other recent posts about how money is created focusing on the banking system rather than the government. Banks do not create money, if we’re defining money as the national fiat currency. Only the national government itself can do that.

But they create credit. The broad public doesn’t care in general terms as it looks like much the same to them.

And by law, they are required to make credit as good as money, so the system is set up in a way that the government is forced, to avoid collapse, to provide HPM and liquidity whenever is needed to keep the inflationary nature of the system and avoid collapse.

It’ all about expectations of asset classes holding certain value, otherwise the “money” pyramid would collapse, so in practice policy is to let banks do whatever they want and create quasi-money that will b made as good as money by the government when required.

This is the reason why CB’s CANNOT control the upper bound of interest rates regardless of their policy. When the economy is ‘hot’ CB’s don’t have control over it, it’s just extend and pretend. Additionally, what they can do, though, is provide a lower bound, so when they set up interest rates higher while an economy is hot they are adding to the positive feedback loop throught the interest income channel (specially the more extreme the rates are set, the worst is the income).

Either CB’s don’t understand the systems they operate, or they do and are malicious, or a mix of both. Will leave that up to the reader.

This is an important point, as Eric mentions “In September 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers disaster led to a panic and the Fed responded by providing large amounts of emergency advances

The Fed bought outright long-term treasuries but also long-term private securities (MBS guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae).”

The question is what sort of financial products the Fed will decide to support in the future rather than focus on a ‘QE for the people’.

The repo system it has set up a conduit into the money market/tri-party repo system does not bode well in this respect.

This is confused. The Fed “outright bought” securities ONLY as a result of QE. That started in March 2009. The emergency programs were all lending facilities.

It bought those securities to lower long term interest rates and to try to stimulate more home buying.

It was a “goose asset prices” strategy.

Yeah, it’s interesting that some of the major actions of the government are already being forgotten. Two of the ways we know banks cannot actually create money is that their stock prices fell (the general public didn’t want to put their money on the line) and the big gamblers lined up to become bank holding companies to get special access to government funds.

Bank lending does not create credit. It moves it around, exchanging some forms of credit for others. Only government allows banks, in aggregate, to create fiat.

That is nonsensical. Legislation by its very definition is an act of public policy, not private banking.

Banks credit and then, after the fact, seek deposits to match balance sheets and reserves with the CB. Banks create credit ex-nihilo, yes, they do (usually lending against some collateral). Z1 is not equally matched by the quantity of public debt (which is the only ‘fiat’ that is circulating around the system), public debt is highly leveraged (on the pyramid of moneyness it’s the one thing backstopping through collateral all other forms of credit).

“That is nonsensical.”

It isn’t, when you withdraw money the banks are obliged to provide you with cash. Well, at least that’s how it works in most of the world (until bankers successfully lobby on ‘banning cash’ to get more control over the system and the conflation between credit and fiat deeper).

This is fact. The Bank of London paper basically proves that the banking sector creates money through credit and in fast sums.

First, let me make a correction. It is not known as the Bank of London Paper, but the Bank of England Paper, also called “Money creation in the modern economy.”

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

In the opening preamble, it makes this statement. “This article explains how the majority of money in the modern economy is creating by commercial banks making loans.”

Forgive me for saying this, but it must be said. This paper fully discredits Loanable Funds. It flat out states “this bank creates money through lending.” In the parlance of science is called EVIDENCE! And evidence trumps argument.

Here is Prof Steve Keen discussing its findings in a bit more detail. (22 minutes, shortest one I could fine.)

https://youtu.be/ICKD83sZ-qg

I wanted to respond to this separately. That is quite the pile of hogwash. The ‘broad public’ cares very much about the thievery of the banksters. TARP specifically (EESA) was one of the most despised pieces of legislation in the entire Reagan-Obama era. It was colloquially referred to as the Taxpayer Anal Rape Program.

The very reason the authoritarians bailed out the banksters (and not just through TARP, through a whole range of actions) was because the broad public didn’t want IOUs issued by the banks.

We can debate whether or not bailouts are necessary, but come on, no one can possibly claim the general public doesn’t care about the difference between unsecured lending and lending secured by the printing press of the United States Federal Government.

What do you think would happen, for example, if the government reduced the FDIC guarantee to $5,000?

For most intents and purposes it doesn’t on a practical daily basis. Most of the transactions that are done through the system have originated from credit, not from HPM.

You are conflating the quantity of credit withstanding in the system (Z1) with a narrow amount of high-powered money that is in the system. That’s exactly what I’m talking about: for practical purposes we cannot distinguish and care about both on a daily basis.

The FDIC is what guarantees “by law” that the credit is actually as good as money. Banks have charters to extend credit guaranteed by the state, but that credit is not ‘fiat’, although the system is set in a way that the government is FORCED to avoid collapse to make it as good as money (and that’s exactly what happens when shadow money collapses and you get a TARP, massive QE’s etc. to backstop the system).

“The FDIC is what guarantees ‘by law’ that the credit is actually as good as money.”

What asset secures the guarantee the FDIC makes? Does the full faith and credit of the United States stand behind the FDIC. Or only a Treasury Account at the Federal Reserve (a liability of the Federal Reserve Bank) with a finite balance that was funded by credits that were matched by debits to commercial bank reserve accounts according to a prescribed contribution formula? I ask rhetorically.

Does it really matter? Either way, there is no money in it, though the FDIC participates in the government’s power to create money by spending it into existence. I guess that must be the ultimate asset.

thank you Maroon Bulldog. At least somebody gets it! There is no real money any where in the system. It’s all credit.

You’re welcome. I’ve learned a lot by thinking through your comments.

Agreed. That’s why I think the ‘banks create money’ meme is so fascinating. It feels like a last ditch effort to assure ourselves that, no really, there is lots of money in the banking system. Honest, trust us!

The FDIC is funded by commercial banks, by law.

That’s not the real story. Deposit insurance is widely recognized to be set at a level that is too low to handle our once every decade or so financial crises. The FDIC got a Congressional appropriation to fund the Resolution Trust Corporation in the S&L crisis, and the need to pass TARP was also in large measure to rescue Citi and Bank of America, the sickest of the bunch.

You are making claims that are not consistent with the actual facts. While not a complete list, some of the points worth mentioning include:

1) a significant number of people hate banks so much they don’t have a bank account at all,

2) of people that do have bank accounts, a significant number have only nominal funds in those accounts,

3) the public has so little faith in banks having money that government has to backstop deposits through the FDIC (however effective it would actually be in a systemic crash),

4) the public has so little faith in banks (and I mean the term very broadly for all our financial fraudsters) having money that their stock prices fell to nothing – completely bankrupt – without massive, unprecedented action to backstop the major players, from Goldman Sachs to Freddie Mac,

5) this notion that government has to bail out the banksters is rather dangerous. Prosecution and bankruptcy are how market-based economics works. You are directly advocating totalitarianism. I reject your march to fascism.

Godwin’s Law has been invoked.

The distinction is meaningless, as the mechanic the banks perform is basically number entry on the ledger. A number that can then either be converted to physical cash, or used as an alternative to physical cash in an transaction.

The fed funds only come into play related to the “reserve requirements”, and those “requirements” only really pertain to individual savings. Corporate “savings” and various other accounts are not covered by the reserve requirement at all.

Fed funds, as best i understand, never ever converted to physical cash. They are basically an accounting mechanic to try to keep bank lending in check, and one that the banks have 1001 way to sidestep.

Forget about Fed Funds. They are irrelevant. Just merge all the banks into one banking system in your head and it all becomes more clear. Fed Funds are a distraction to understanding the core principles.

‘In terms of the floor, other Fed account do not qualify to receive interest on their account so they have an incentive to keep lending Fed Funds in the market even if FFR is below IOR.’

This is a bit out of date. After testing the facility for a couple of years, the Fed now uses ON RRPs (Overnight reverse repos) to set a floor on its policy rate.

More background on the testing of ON RRP facility, which began in Sep. 2013:

The ON RRP experiment “went live” with the Dec. 2015 rate hike, so it’s still early days. The Fed’s own daily Fed funds rate series indicates a rock-steady range of 0.36 to 0.38 percent since Dec. 17th, except for a few days during the new year weekend.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/DFF

Thanks.

there is no real Fed Funds market with over $2 trillion of excess reserves in the banking system. Nobody needs to trade Fed Funds. Any reported trades are probably fakes just like the banks faked the Libor rates.

As for the Fed’s reverse repurchase program that is just a way of ginning up a fake rate that doesn’t reflect a true third party market.

“Because the Fed has a monopoly on money”? Am I the only one who thinks the fed is creating a “money” that is not money but is, in fact, a synthetic commodity? So this fed money is neither a medium of exchange or a store of value even tho it functions as both. So when the SHTF the whole thing implodes, because simple logic. Money has been transformed into the commodity itself. Nutty as hell. We should start following this trail and look at “commodities”. Since money is not a real commodity but had been tweaked to mimic one. We might as well replace the Fed with a computer. But make sure the app has a rock solid definition that money cannot be, cannot ever be, a commodity. That’s just fubar.

because ‘full faith and credit’ can only ever be used as a medium of exchange; forget store of value…

” … money is not a real commodity … . We might aw well replace the Fed with a computer.”

We live in a world of electronic payment systems and automated clearinghouses. We have been living in this world for a long time now. In this world, information stored in a computer is money.

Fiat money is also debt. Debt is not a real commodity. Debt is a legal obligation. Debt is information.

What makes a federal reserve note pass as money? The information printed on it. What makes a coin pass as money? The information stamped on it. Money is information, not the medium in which it is recorded.

This information money can’t be a store of value. Money as a store of value is only a quaint notion.

Money is the unit of account.

Isn’t it a perversion of the system when recently insolvent institutions that are continually committing fraud and entering into fraud settlement agreements can borrow cheaply? How is it that such institutions which should be high credit risks can borrow at near zero and mark up the cost of capital to individuals who have superior credit ratings? And when high risk can borrow at near zero, then a sure thing like cash has to return less than zero.

‘Isn’t it a perversion of the system when … institutions which should be high credit risks can borrow at near zero and mark up the cost of capital to individuals who have superior credit ratings?’

Why, yes. In all pre-1913 crises (e.g. 1907, 1893, 1873, etc.), overnight rates soared as creditworthiness came into question. This recurrent phenomenon is precisely what the Federal Reserve bank cartel was designed to invert.

Now short rates plunge in crises, guided lower by the Fed. It’s as unnatural as water flowing uphill.

The price paid for this heroic intervention is a longer business cycle, typically culminating in a bubble followed by a spectacular crash. In other words, increasing cyclical amplitudes, until one day a Richter 10 financial earthquake shatters the whole structure.

“The price paid for this heroic intervention is a longer business cycle, typically culminating in a bubble followed by a spectacular crash.”

Also, and especially in this day and age, a recognition by more and more people about what a ridiculous fraud the whole system is.

YES and the Richter 10 financial earthquake draws ever closer!

The observation that overnight rates soared in all pre-1913 crises reminds me of an interview in which Thomas Sowell described the Fed as a cancer, and said we ought to eliminate it. When the interviewer asked what we would replace it with, Sowell said we should revert to what we had before. Then he quipped, “when you remove a cancer, what do you replace it with?”

There is NO true money in the modern fiat monetary system. It’s all debt! Deposits at a bank are debt obligations of the bank. They can be exchanged for sovereign currency in the form a “federal reserve note” which is just a zero coupon perpetual note in bearer form. These federal reserve notes are listed as liabilities of the central bank even though it has had no obligation to redeem these liabilities for several decades now. Not to worry though because the central bank backs all those federal reserve notes with U.S. government bonds which is where the funny parts comes in. Those bonds which back the federal reserve notes are payable in federal reserves notes. In other words modern money is really just an enormous daisy chain when properly understood, and all money, both bank money and sovereign money, is in reality a credit instrument. This is obvious to anyone in the case of Argentina for example, but when it comes to the dollar we delude ourselves into believing it is something else. All fiat money including the dollar is a credit instrument because there is a counter-party involved, either the banking system or the sovereign agent in the form of a central bank.

Very few people seem to understand this. As some point this will all become clear and when it does the forty year experiment in fiat money will come to an end. It’s an enormous Ponzi scheme that can’t continue! You can run a purely fiat monetary system in theory if it is well regulated and carefully managed but this one was run as a pyramid scheme and the gig is nearly up. They can’t raise rates because there is too much debt in the system and they can’t print money indefinitely because at some point confidence will be lost.

It’s going to get very interesting very soon.

Yes all monetary instruments are debt instruments. And it has always been like that. A gold coins is an IOU of the king with an embedded collateral. The gold content is not the monetary instrument the coin is. Payment in gold bullion is a payment in kind, not a monetary payment.

Will do a post later on money. BTW, FRNs are not perpetuals, they have a zero term to maturity (gov will take FRNs back in payments at anytime). Otherwise , given that FRNs are zero coupon securities, their fair nominal value would be zero (you would go to the store and the casher would take your $20 for $0; I.e.would not take it). We know that the fair nominal value is face value, everyday we experience it when we go shopping. That can only be achieved is an instantaneous maturity.

Hey Eric I don’t mean to quibble but I am not sure it’s that helpful to say: “Yes all monetary instruments are debt instruments. And it has always been like that. A gold coins is an IOU of the king with an embedded collateral.” This suggests that fiat systems and commodity systems are both fundamentally debt based. Your point about the “embedded collateral” is a huge difference! Again I am not sure we disagree because the concepts get a bit abstract which makes the semantics tricky.

King made a promise when he issued the coins: to take them back in payment at face value. If someone makes a promise he is indebted to the issuer.

Again like a bond issuer promise to take back its bond at maturity, monetary issuer promise to take them back at maturity (which here is “at any time” at the which of the holder).

Yes coins made with precious metal help the bearers by:

1- allowing the bearers to still be solvent if king default (i.e. not take back their coins at the promised face value): they could sell the gold

2- giving them some protection against inflation risk as long as gold price moves in a way that hedges that.

Now having coins made of precious metal also creates some problems. Will expand later

But the gold is not the money. In the same way in a mortgage, the house is not the mortgage, the promissory note is.

Second sentence should be “indebted to the bearer”

Yes, understood. Even gold coins have a credit component in the sense that the sovereign is the sovereign and hence makes the rules. As the sovereign has committed to some terms there is in fact a type of obligation, component to the the gold coin. Not sure it meets the normal meaning of the word debt or credit but I agree that there is a type of credit component to commodity money. But as you point out, precious metal coins do help bearers in a couple of important ways.

As I mentioned, I am no gold bug but the thing about gold is that it forces some constraints on monetary systems. Those constraints can of course be abused and broken, but I view them as preferable to a system with no rules and constraints.

Furthermore I would bring up one every important practical point. Irrespective of whether the sovereign breaches its promises, the simple fact is that gold has been money for thousands of years across almost all civilizations. So irrespective of who stamps and issues the coins, gold has always been money and still is. The Iranians end ran the financial sanctions by using gold as money and the world’s central banks still hold hundreds to thousands of tons of gold in their vaults which tells you all you need to know. It’s not stamped and engraved coins, rather it exists in 400 ounce “good delivery” bars. No central banker in the world dares to equate gold with money because they are currently running, and screwing up, the world’s greatest fiat monetary experiment which is just a confidence game at its core.

Look we are never going back to carrying around gold coins, but there is a legitimate question of whether gold will officially re-enter the monetary system, in some form, at some point in the future. Anyone who dismisses this possibility is ignoring thousands of years of monetary history.

I love the irony of this video taken in the Bank of England’s vault were they explain the money creation process. Gold isn’t money but they keep a few million pounds of it sitting in the basement because it’s shiny and pretty!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvRAqR2pAgw

“King made a promise when he issued the coins: to take them back in payment at face value. If someone makes a promise he is indebted to the bearer.”

This is a promise considerable value, because sliver coins more a face value that was considerably higher than the market value of the weight of silver contained in them. When the United States last issued silver dollar coins for circulation, back in the 1930’s, they contained about thirty-five cents worth of silver by weight.

When the market price of the weight of silver in a coin rises above the coin’s face value, the coin will be melted down and the metal sold for bullion.

Of course, there is nowhere near a quarter’s worth of anything the the quarters the U.S. mint issues today. Polish the information off one of these coins, and all you’ve got left is a slug.

When the coin is melted down for bullion, the issuer’s debt and the bearer’s asset claim against that debt are both released (extinguished), but no one minds, because they had to become worthless for that to happen.

good points Eric and I agree with you even though the semantics can be challenging. I am no gold bug and agree that gold coins are also monetary instruments. Yet you point out an important distinction, the embedded collateral aspect. The subject of money is far more esoteric and abstract than most people recognize. And I agree that FRNs are not perpetual notes for precisely the reason you state; they can be used to settle tax obligations which is fundamentally where their value originates. They nevertheless do have certain characteristics of a perpetual note. They are legal obligations of the Central Bank and the Central bank acknowledges them as such by listing them as liabilities on their balance sheet. So if it they are liabilities what is owed to the holder by their issuer? NOTHING! If you try and redeem one of these “notes” with the issuer by turning in a five dollar bill they will tell you to get lost and if you persist they may try and satisfy your request by handing you five ones, but that’s all you are getting. So they are very much perpetual notes in some sense. As you know this is a legacy issue from when they could be redeemed for “specie”. When you had the specie you had the real money. Yes it may have been embossed by the sovereign making it official money but it really made no difference whether you held the official money or a lump of the commodity. The lump of gold or silver could always be exchanged for it’s monetary value either, officially by paying a small seignorage fee and having your lump of gold turned into coins, or by payment in kind as you acknowledge.

My problem with the current fiat/credit based monetary system is that it is totally elastic and that is why we are in the midst of monetary disaster. The world has been on a nearly 40 year credit binge and it’s not going to end well. With a commodity anchoring the system, there is a limit to credit and money creation. Technically you don’t need to link money to a commodity. But what you do need at a minimum is some bloody rules to keep the sovereign and its banking partners from stuffing the world full of their credits which is where we sit today. With no “anchor” to the system it’s just an enormous Ponzi scheme!

As for the “fair nominal value” of our FRNs, sure they appear on the face of it to trade at par but that’s just an issue of timing and perspective. Once devaluation and inflation set in the value of a currency collapses so what could once be had for $20 may one day cost $50 and their “fair nominal value” is therefore uncertain.

Keep up with your series, it’s great and very informative!

Don’t confuse “redeemability” and convertibility. The issuer of a monetary instrument does make at least one promise: to take it in payments at face value. That is what is owed to the bearer.

In the case of banks, beyond the ability to pay bank debts with bank monetary instruments, there is also a conversion clause: the bank promises to exchange for cash on demand.

There are two things that influence the value of a monetary instruments:

-change in its fair price: nominal value at which it circulates

-inflation/deflation

We are no longer accustom to the first type of change because now the ability to redeem is well establish (it took quite a while to get that straight with issuers not understanding the importance of making that promise and not having extablish means to implement that promise). In the past, some issuer use to never promise to take their monetary instruments ever! Of course fair value fell to zero (bitcoin, I am looking at you now)