This is Naked Capitalism’s special fundraiser, to fight a McCarthtyite attack against this site and 200 others by funding legal expenses and other site support. For more background on how the Washington Post smeared Naked Capitalism along with other established, well-regarded independent news sites, and why this is such a dangerous development, see this article by Ben Norton and Greenwald and this piece by Matt Taibbi. Our post gives more detail on how we plan to fight back. 347 donors have already supported this campaign. Please join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal.

Yves here. Hubert Horan has graciously offered to add one more post to what was originally a four-part series. He will discuss reader comments and issues not addressed in the series proper in an additional article. Part four and his extra piece will run Monday and Tuesday of next week.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants.

This is the second of a series of articles that will use data on industry competitive economics to address the question of whether Uber’s aggressive efforts to completely dominate the urban car service industry has (or will) increase overall economic welfare.

A positive answer to this question requires clear evidence that Uber can (or is on the verge of being able to) operate on a sustainably profitable basis in a competitive market, clear evidence that Uber can produce urban car service significantly more efficiently than the traditional operators it has been driving out of business, compelling evidence that Uber’s business model is based on major product/technological/process breakthroughs that create huge competitive advantages incumbents could not match, and that Uber can earn returns on the $13 billion its investors have provided within the normal workings of open, competitive markets, while ensuring that the gains from its efficiency and service breakthroughs are shared with consumers.

To state the question another way, does Uber’s meteoric growth and unprecedented $69 billion valuation reflect an efficient reallocation of resources from less productive to more productive uses?

The first article presented evidence that Uber is a fundamentally unprofitable enterprise, with negative 140% profit margins and incurring larger operating losses than any previous startup. Uber’s ability to capture customers and drivers from incumbent operators is entirely due to $2 billion in annual subsidies, funded out of the $13 billion its investors have provided. That P&L evidence shows that Uber did not achieve any meaningful margin improvement between 2013 and 2015 while the limited margin improvements achieved in 2016 can be entirely explained by Uber imposed cutbacks to driver compensation.

Thus there is no basis for assuming Uber is on the same rapid, scale economy driven path to profitability that some digitally-based startups achieved. In fact, Uber would require one of the greatest profit improvements in history just to achieve breakeven.

Unlike other well-known tech “unicorns,” Uber has not created a totally new product or dramatically redefined a traditional market; it is not “disrupting” incumbent operators with a totally new way of doing business but is driving passengers from point A to point B in cars, just like traditional urban car service operators always have. To achieve the overwhelming industry dominance that Uber is seeking it would need to find ways to provide service at substantially lower costs.

This article presents evidence about the cost structure of traditional operators, and evaluates, based on Uber’s actual practices and historical industry evidence, whether Uber has a meaningful cost advantage in any of these cost categories, or the potential to achieve substantially lower unit costs as it grows. Can Uber’s massive losses and investor subsidies be justified as an “investment” that will yield returns in the near future once its potential efficiency advantages (and scale economies) kick in?

Uber Extended the Industry’s Longstanding Segregated (Corporate/Driver) Business Model

When considering financial and cost data, keep in mind that taxi service is provided under a two-part business model, with drivers classified as independent contractors. Since the 1970s most traditional taxi companies have actually been leasing companies; drivers pay a fixed lease fee covering the costs of vehicle ownership and maintenance and corporate overhead services such as dispatching, branding/marketing and credit card processing. Traditional drivers retain all of the money paid by passengers, but pay for gas and bear the risk that fare revenue on a given shift might not be enough to provide meaningful take home income after covering the leasing fees and the workman’s comp and health insurance costs taxi companies do not pay for.

The Uber model takes the contracting model further by additionally shifting all vehicle costs and capital risk to drivers. Uber takes 30% of passenger revenue but only provides corporate overhead services. To evaluate questions of efficiency and competitiveness one needs to consider the entire (corporate+driver) business model since neither business model can work in the marketplace unless both the corporate entities and their driver contractors can achieve reasonable earnings.

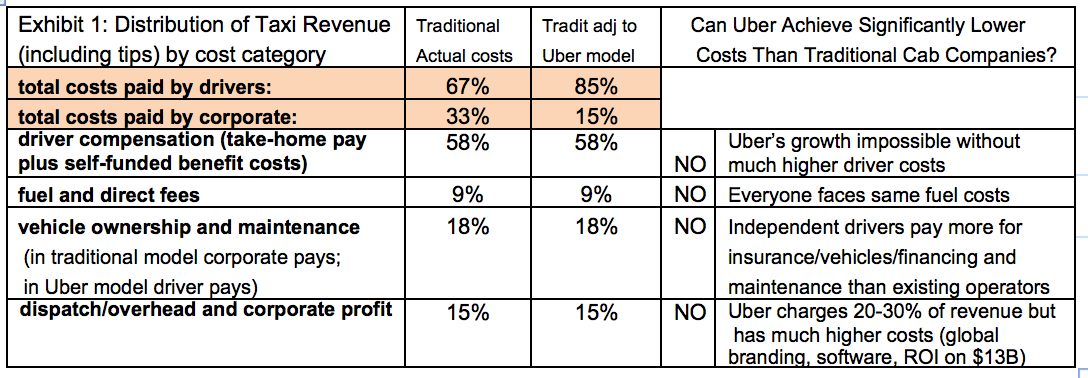

85% of Taxi Costs Are the Direct Costs of Vehicles, Fuel and Drivers

There are four major components of urban car service costs: driver compensation (take home pay plus the benefit costs they must cover), fuel and fees directly related to passenger service (credit card fees, airport access fees, tolls, cell phone charges), vehicle ownership and maintenance, and corporate overhead and profit (including dispatching and branding/marketing). Detailed cost data from studies of traditional operators in Chicago, San Francisco and Denver showed that 58 cents of every gross passenger dollar (fares plus tips) went to driver take home pay and benefits, 9 cents went to fuel and direct fees, 18 cents went to vehicle costs and the remaining 15 cents covered corporate overhead and profit. [1] These percentages can vary slightly depending on fuel price swings and local practices, but reasonably reflect the relative size of the four cost categories at traditional operators under current conditions.

Uber is the Industry’s High Cost Producer

Can Uber produce urban car services more efficiently — at sustainably lower cost — than traditional operators? Can Uber’s success in driving incumbents out of business and achieving the largest venture capital valuation in history be explained by a powerful competitive efficiency advantage?

If one examines the four components of industry cost it becomes apparent that the opposite is true. Uber not only lacks the major cost advantage that a company seeking to drive incumbents out of business would be expected to have, but actually has higher costs than traditional car service operators in every category, except for fuel and fees where no operator can achieve a cost advantage.

These structurally higher costs are fully consistent with the ongoing, multi-billion dollar losses documented in part one of this series, and the finding that Uber’s rapid growth is driven by massive investor subsidies, and not by superior service or efficiency.

The first two rows on Exhibit 1 quantifies the difference between the two business models. Traditional taxi leasing companies pay 33% of these costs (vehicle and corporate costs) plus the vehicle capital risk; since the Uber model shifts vehicle costs and risks to drivers, they are only covering 15% of the total cost structure and bear none of the capital risk. .

Higher driver compensation. Recent in-depth studies from Chicago, Boston, New York and Seattle show that the 58 cents retained by traditional taxi drivers provides hourly take-home rates in the $12-17 range (in 2015 dollars) and that full-time drivers can only realize those hourly averages if they work 60-75 hours a week.[2] True pre-tax earnings are even lower since workman’s compensation, health insurance and some miscellaneous expenses must be covered out of take-home pay. Recognizing that big city taxi drivers are forced to work much longer hours than typical drivers, this data is consistent with Census Bureau analysis which estimated the average wages in the broad category of taxi and limousine driver as $32,444 per year and $13.25 per hour (in 2015 dollars).[3]

Uber needed extraordinary traffic and revenue growth in order to fuel the growth of its (now $69 billion) financial valuation. In addition to the massive subsidies for uneconomical fare and service levels needed to shift passengers away from traditional operators, Uber needed to subsidize uneconomical driver compensation premiums large enough to get hundreds of thousands of drivers to abandon other operators and sign up with Uber.

Uber’s above-market driver compensation meant its drivers were often more professional and drove better maintained cars than their lower paid counterparts. In a competitive market drivers would have no incentive to drive for Uber if it paid the same as traditional operators (why take on all the vehicle expense and risk for the same $12-17/hour Yellow Cab pays?) And it would be impossible for Uber to ever achieve a driver cost advantage over incumbents without paying significantly less than traditional operators, which would require pushing average take-home wages down to (or perhaps below) minimum wage levels

Higher vehicle costs. It is inconceivable that hundreds of thousands of independent, poorly financed Uber drivers Uber could ever achieve lower vehicle ownership, financing and maintenance costs than professional fleet managers at a reasonably managed traditional operator, or do a better job balancing long-term asset costs against local market revenue potential. Shifting operating costs and capital risk from Uber’s investors onto its drivers does not eliminate them from the overall business model, and actually makes them higher.

Every other transport industry depends on highly centralized management using highly sophisticated systems to ensure that capital assets are highly utilized and tightly scheduled around market demand. The Uber business model implies that all these industries are horribly wrong; decentralizing asset purchasing, maintenance and scheduling to isolated low-wage workers would not only reduce costs, but create an efficiency gain large enough to drive all incumbent operators out of business. No one has produced any economic evidence demonstrating that the Uber view might be correct.

Higher dispatch and corporate costs. Traditional taxi owners take 15 cents of each passenger dollar to cover dispatching, corporate overhead and profit while Uber currently takes 30 cents. But Uber’s costs are much, much higher; even though they provide less than half the service of traditional companies. The P&L data clearly shows these charges come nowhere close to covering Uber’s actual corporate expenses. Unlike traditional cab companies, Uber fees need to cover the cost of global marketing, software development programs, branding and lobbying programs, the huge market development costs of Uber’s expansion into hundreds of new cities and must also fund a return on the $13 billion its owners have invested.

Uber Used “Strategic Misinformation” To Elide Its Catch-22 Problem With Driver Costs

Uber’s above-market drive pay premiums created a competitive Catch-22; they fueled the rapid growth that was critical to its unprecedented valuation and established the perception that Uber had better drivers and vehicles. However, that also meant Uber would have a hopelessly large cost disadvantage in the biggest and most important cost category. Cutting driver compensation back to previous market levels would also halt growth and undermine Uber’s perceived quality advantage.

Uber dealt with this Catch-22 with a combination of willful deception and blatant dishonesty, exploiting the natural information asymmetries between individual drivers and a large, unregulated company. Drivers for traditional operators had never needed to understand the true vehicle maintenance and depreciation costs and financial risks they needed to deduct from gross revenue in order to calculate their actual take home pay.

Ongoing claims about higher driver pay that Uber used to attract drivers deliberately misrepresented gross receipts as net take-home pay, and failed to disclose the substantial financial risk its drivers faced given Uber’s freedom to cut their pay or terminate them at will. Uber claimed “[our} driver partners are small business entrepreneurs demonstrating across the country that being a driver is sustainable and profitable…the median income on UberX is more than $90,000/year/driver in New York and more than $74,000/year/driver in San Francisco”[4] even though it had no drivers with earnings anything close to these levels.[5]

After these claims were readily debunked[6] Uber responded with allegedly “academic” research (which Uber administered and paid for) which claimed Uber drivers earned more than traditional taxi drivers but made no effort to calculate actual net earnings, and concealed the fact that Uber salaries were massively subsidized while traditional taxi salaries were constrained by actual passenger revenues.[7]

In mid-2015, after hundreds of thousands of drivers were locked in to vehicle financial obligations, Uber eliminated driver incentive programs and reduced the standard driver share of passenger fares from 80 to 70 percent.[8] This transfer of passenger dollars from Uber drivers to Uber investors drove all of its 2016 margin improvement, but also eliminated much (if not all) of the economic incentive that got drivers to switch to Uber in the first place.

An external study of actual driver revenue and vehicle expenses in Denver, Houston and Detroit in late 2015, estimated actual net earnings of $10-13/hour, at or below the earnings from the studies of traditional drivers in Seattle, Chicago, Boston and New York and found that Uber was still recruiting drivers with earnings claims that reflected gross revenue, and did not mention expenses or capital risk.[9] In the absence of artificial market power, it is not clear how Uber could sustain either higher driver compensation, or the misinformation that created the false impression that it pays significantly better than traditional operators.

Uber Cannot Grow Into Profitability

Many successful startup companies experienced large initial losses but used scale and/or network economies to dramatically improve cost competitiveness and margins as they grew, although Uber’s losses to date ($2 billion a year) are significantly larger than any previous tech startup. But as noted in the first article in this series, the urban car service industry has never displayed evidence of significant scale economies,[10] Uber’s actual financial results show none of the rapid margin improvements that would occur if strong scale economies actually existed, and Uber has none of the characteristics of the digital companies that were able to “grow into profitability.”

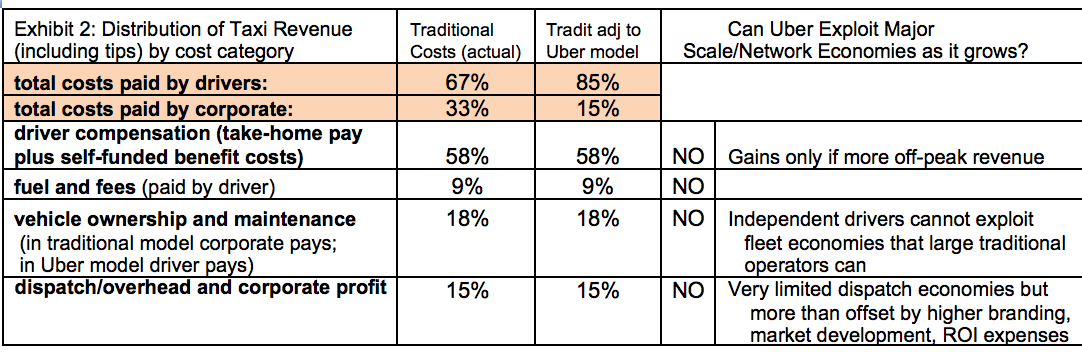

Exhibit 2 summarizes scale economy issues for each major cost category. There are no scale economies related to the 85% of costs related to direct operations; each shift involves one vehicle and one car regardless of the size of the company. This is why there has never been any natural tendency towards significant concentration in individual taxi markets, and why taxi companies rarely expanded beyond their original markets.

The revenue productivity of drivers could increase if more off-peak and backhaul passengers could be found, but revenue productivity is not a function of company size. Uber’s decentralized business model precludes the efficiencies integrated operators can achieve such as volume purchasing of vehicles and insurance and the use sophisticated systems to optimize asset acquisition and utilization against volatile demand patterns.

Uber’s economics are fundamentally different from other well-known startups that successfully used scale economies to grow into profitability. These were companies in fields such as social media or online retailing whose purely digital products could be expanded globally (and into new markets) at extraordinarily low marginal cost. Unlike an urban car service provider, direct labor was a tiny component of these companies’ overall cost structure, and most had no competition (entirely new products like EBay or Facebook) or were facing competition with enormously higher direct operating costs (online retailers vs. brick-and-mortar incumbents).

Unlike digital companies, Uber actually faces negative expansion economies since each new market raises entirely unique competitive, recruitment and political lobbying challenges. Uber’s unit expansion costs appear to have increased dramatically as it expanded outside the United States.

Uber also has no potential to exploit the network economies that some purely digital companies used to drive major profit improvements. In these cases (EBay’s exchange market, Google’s search function, Facebook’s social media product) the development of a strong user base makes the product significantly more efficient and more attractive to other users. This locks-in existing users, fuels growth, and makes it nearly impossible for later entrants with smaller user bases to compete.

By contrast, neither Uber’s ordering app, nor the ordering apps of other operating companies create these network economies or locks-in users the way EBay and Facebook and Google have. In a competitive market, people will use the app of companies like Uber or American Airlines if they can profitably provide good prices and service, but no one will abandon Yellow Cab or JetBlue just because a lot of other people have the bigger company’s app on their phones.

Will the growth of Uber increase or decrease overall economic welfare?

The first post in this series laid out the evidence of Uber’s staggering losses. Uber has grown because consumers have been choosing the company that only makes them pay 41% of the cost of their trip; there is no evidence that taxi customers in a competitive market would pay more than twice as much for the service quality advantages Uber investors have been subsidizing. Incumbent operators have been losing share and filing bankruptcy because they cannot compete with Silicon Valley billionaire owners willing to finance years of massive subsidies as they pursue industry dominance.

This post focused on the cost structure of the urban car service industry in order to demonstrate that Uber has structurally higher costs than its competitors, and lacks the scale economies other startups have used to rapidly reduce unit costs. In the absence of the massive scale economies that digital companies enjoy, there is a fundamental contradiction between incurring the cost of providing higher levels of capacity and service quality, and achieving costs low enough to drive incumbents out of the market.

If one examines the components of urban car service costs, there is no basis for claiming Uber could ever eliminate its structural cost disadvantage, much less achieve the massive cost advantage needed if its march to industry dominance is to be justified on economic welfare terms. The findings that Uber is the industry’s high cost producer and lacks any meaningful scale economies are entirely consistent with the P&L data presented in the first post.

In most industries, years of evidence about massive losses, the lack of margin improvements, and structurally uncompetitive costs would be sufficient support for the conclusions that the displacement of incumbent companies by the new entrant had not increased economic welfare, and that the capital markets that had funded the new entrant were not allocating society’s resources to more productive uses. Silicon Valley funded tech unicorns have regularly claimed that these traditional financial standards are inadequate because they have been introducing massive product/technological/process innovations that totally “disrupt” traditional industry economics, and the public discussion of Uber has been dominated by claims about its innovative breakthroughs.

In reality, if the alleged innovative breakthroughs have not made major impacts on service, efficiency and profitability, then they are not really innovative breakthroughs. In the case of Uber the question becomes why haven’t these “disruptive innovations” yet produced competitive cost advantages or profits?

The next installment of this series will examine a range of claimed Uber “innovations”—sharing economy efficiencies, market growth, Uber’s app and surge pricing—and examine whether any of these could constitute the type of large, sustainable competitive advantage that could eventually justify Uber’s growth and industry dominance in economic welfare terms.

_____________________________

[1] Seattle Consumer Affairs Unit, Seattle Taxicab Industry Revenue And Operating Statistics (2010); and Taxicab Industry Revenue Flow Diagram; San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, Meter Rates & Gate Fees, prepared by Hara Associates (Aug 2013); author’s analysis of Denver taxi operators annual financial reports to the Colorado Public Utility Commission. All data was restated in 2015 dollars. Seattle data assumed the use of Ford Crown Victoria and higher 2010 fuel prices and were adjusted to reflect the higher original cost of hybrid vehicles and the lower 2013 fuel prices reflected in the San Francisco and Denver data. Driver take-home pay must cover workman’s compensation and any health insurance costs drivers incur.

[2] Chicago Business Affairs and Consumer Protection, Taxi Fare Rate Study, prepared by Nelson Nygaard Associates (2014); Boston Taxicab Consultants Report, prepared by Nelson Nygaard Associates and Taxi Research Partners (2013); Seattle Consumer Affairs Unit supra note 15; New York Taxi and Limousine Commission, New York City Taxicab Fact Book, prepared by Schaller Consulting (2006). Seattle drivers earned $12.14/hour working 10.2 hours per day; Chicago drivers earned $12.94/hr @ 12.8 hrs/day; Boston drivers earned $14.61/hr @ 15 hours/day and New York drivers earned $17.51/hr @ 9 hours/day. All pay data adjusted to 2015 dollars.

[3] Census Bureau American Community Survey data excluding drivers working 40 hours or less. Transportation Research Board, Between Public and Private Mobility, Examining the Rise of Technology-Enabled Transportation Services, 52-3 (2015)

[4] Uber was claiming that its drivers made more than double the actual earnings of traditional New York taxi drivers, and more than the average wages of workers in the tech industry., McFarland, M., Uber’s Remarkable Growth Could End The Era Of Poorly Paid Cab Drivers, Washington Post, 27 May 2014.

[5] “In several months of reporting on Uber, I have yet to come across a single driver earning the equivalent of $90,766 a year…. despite broadcasting the $90,766 figure far and wide, Uber has so far proved unable to produce one driver earning that amount.” Griswold, Alison, In Search of Uber’s Unicorn: The Ride-Sharing Service Says Its Median Driver Makes Close To Six Figures. But The Math Just Doesn’t Add Up, Slate, 27 Oct 2014. These figures appeared to have resulted from extrapolating the hourly receipts of drivers who only drove a handful of peak-demand hours a week.

[6] Kedmey, D., Do UberX Drivers Really Take Home $90K A Year On Average? Not Exactly, Time, 27 May 2014. Rail, T., Fact checking Uber’s claims about driver income. Shockingly, they’re not true, Pando Daily, 29 May 2014. Singer, J., Beautiful Illusions: The Economics of UberX, Valleywag, 11 Jun 2014.

[7] The academic was Alan Krueger of Princeton, a former White House colleague of Uber executive David Plouffe. Issac, Mike, Hard-Charging Uber Tries Olive Branch, New York Times, 1 Feb 2015.

[8] Huet, Ellen, Uber Tests Taking Even More From Its Drivers With 30% Commission, Forbes, 18 May 2015.

[9] O’Donovan, Caroline & Singer-Vine, Jeremy, Uber Data And Leaked Docs Provide A Look At How Much Uber Drivers Make, Buzzfeed, 22 Jun 2016.

[10] Academic studies found limited scale economies (i.e. to cover the fixed costs of dispatching equipment) that would limit the ability of very small firms to compete with mid-sized firms in the same city, but none large enough to drive high levels of concentration within a given city. Pagano, A. M., & McKnight, C. E., Economies of Scale In The Taxicab Industry: Some Empirical Evidence From The United States. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, (1983).299-313; Dempsey, Paul, Taxi Industry Regulation, Deregulation, and Reregulation: The Paradox of Market Failure. Transportation Law Journal, 24(1),115-16 (1996)

I wonder how much Uber is putting into R&D and acquisitions? It’s clear that the company realizes that it cannot generate long term profit with the business model as it exists today. Witness their investment in Carnegie Mellon’s autonomous driving experts and ongoing tests at “self-driving” cars. I do not believe those efforts will be successful in the near term, but it is a cost that traditional operators do not bear. They do not pay for R&D, they eke out margins with scale, expertise, and local monopolies (taxi medallions). Uber is also interested in autonomous truck driving having acquired Otto. This is another massive expense that also requires massive cash inventions. This market seems more likely to bear success in the short term, at least for highway driving.

And Uber must be hungry for drivers as local sports media is getting saturated with a new Uber campaign called “Get your side hustle on”. Here’s the ad I see most frequently in the Boston media market:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZsbWt6FjlTk

They’re clearly trying to attract a large number of drivers that will sometimes drive and not as full time operators. Perhaps these users just cycle in and out of driving, but keeping a small army of part time drivers can keep the service viable by always ensuring that there is a supply of drivers despite the downsides inherent in driving.

Finally, a small bone to pick with the advantages of online retailing. Amazon has huge costs associated with retailing and always have. It’s biggest advantage, preserved until recently, was the built in discount of not charging sales tax on items. This was a public subsidy of Amazon’s operations for years. Without this subsidy I doubt the operation could have grown beyond selling books.

Amazon still pays no sales tax in some states.

Its funny they are now trying brick and morter bookstores.

They will not put a bookstore or a distribution center in a state that they pay no sales tax.

This is not true anymore. Regardless of physical presence, they are matching state sales tax requirements.

Amazon is a cautionary tale. A few people warned that Amazon’s deep-discount pricing even as recently as 5 years ago was predatory and designed to eliminate competitors, and now that this goal has been achieved to some extent the pricing at Amazon has increased substantially.

Amazon has not eliminated competition. It is the dominant online retailer, but far more transactions still occur at brick and mortar locations.

But they have shrunk competition about as much as they can. They sell everything and they’ll never put every retailer out of business. However, how many bookstores do you see these days? Online, most book sellers are owned by Amazon too. And they’ve done something kind of amazing. they have a marketplace for non-Amazon sellers and compete with them. They make money off of their competition, while also driving their prices down and often driving them out of business.

I suspect they don’t spend a lot on R&D. We had a link a couple of weeks back to an Uber white paper on flying cars. It was largely hypothetical (“If a flying car was to be commercially viable, here is what it would have to look like”) and I didn’t see any evidence of actual research taking place. My overall impression is that Uber was attempting to guide possible research directions without actually doing any themselves, or stumping up for grants.

They are attracting customers who do not have a car, so R&D related to people not buying cars makes some sense.

People also need to study the change in pace of ownership of cars and analyze to see of there are correlations such that individual transport services substitue for car ownership levels. This might be welfare improving or not welfare improving. Cause-effect questions arise as always.

Transport new-ownership rates were quite good in the last two years I think. Low borrowing costs, improving job markets, and pent up demand probably influenced these recent rates. If I am right about the increased rate of ownership by individuals, that is not a good sign for the presumption that a network of transport services is substituting, at least at this scale (once you decide not-to-own you become more dependent on JIT services).

It is interesting to see how the huge sums raised by Uber are being used to entice the auto makers to deal with them, with some sense that they need to protect themselves for the time, should it come, when fewer and fewer people own transport vehicles themselves but adjust their live styles to less or more transport mobility, supported by the several JIT options.

What do you think about uber pool service (when you share a car with fellow passengers going approximately in the same direction)? It seems to be beneficial, as less energy is super and pollution generated per passenger. Do you think it could be replicated by traditional companies and could it be a source of competitive advantage for Uber?

There are already successful incumbent players in the space of ride pooling. One such company is VPSI Inc, who seems to have rebranded themselves as vRide. The difference is that in the past VPSI has been structured as a smaller company with sustainable IT costs and modest growth. However, the rebranding makes it seem like they might be thinking of pursuing a more aggressive growth strategy.

thx, will check out

‘ It seems to be beneficial, as less energy is super and pollution generated per passenger’

short answer: Green-washing Alert!!! Uber IS NOT environmentally friendly unless you’re a Shill ‘expert’.

1. Problem w/UberPool is the same as the problem w/Uber: there is asymmetric information between Uber HQ (ie, an admin in ‘God mode’) and rank-and-file drivers.

Uber HQ sees real-time demand, real-time supply but doesn’t share 100% of that info w/drivers (unless it’s during a ‘surge pricing’ event)

so what happens is that too many drivers chase too few passengers for 20 hours of the day—as the ‘equilibrium’ is oversupply by drivers because (a) Uber doles out lots of unprofitable driver incentives funded by its cash hoarde and/or (b) many drivers don’t fully incorporate all driver costs (such as depreciation or unpaid labor like cleaning your own car) and/or (c) drivers would take their odds getting a fare in an oversupplied area (ie Soho NYC) than travel out to a less dense area (Bronx).

2. Other problem w/Pool is that the commission structure for UberPool makes UberPool less profitable per mile for the driver than a regular UberX fare. I’ll go into the maths if someone wants to see the numbers. Or if you’er an Uber user and notice it’s often more difficult to get a Pool ride on a presumably popular route, it’s probably because your drivers keep declining your Pool request.

cheers, hope i offered a concise explanation.

I agree that we definitely don’t have enough information to compare them, they might be better or worse. Not sure about the second part, it’s always been pretty quick

My mom is legally blind, and after I went to college, she needed a way to cart my sister and her little friend from school to whatever activity she needed to go to and then back home. She used a device called a “bulletin board” at a local college and hired a commuter student who was basically going that way, so instead she did school work at a coffee place instead of her home.

The ride sharing ap of Uber isn’t magic. It can be copied. My aunt slugged in Northern Virginia for decades. People pick strangers up at distant commuter lots and take the HOV lanes into DC. Talk about busting the paradigm. They didn’t even use phones to make this work.

The good routes which make sense will become separate from Uber. My uncle with alzheimers began to use Uber to visit his business and direct his son when my aunt took his license, but now they simply pay commuter students under the table.

Or why not organize car pools using the Internet. Obviously, people can be stupid and occasionally need flashy branding, but why pay Uber for regular routes?

It’s called convenience. Checking boards, etc possibly a number of additional steps such as negotiating, etc. Also older people are more flexible i.e. paying under the table, they know how to grease the real system which is the real world. Millenials can’t do anything without flipping out their smartphones.

Uber is simply another example of the ability of the human mind to convince itself of anything i.e. the investors pouring money are thinking “it will all somehow work out”. But then again who can blame them. Wall St has shown that a dollar can sometimes be worth more or worth less than a dollar and in the end it’s all other people money (OPM).

There’s a lot of worthy elements in what Uber does, but there are serious flaws in the model – mostly driven by the high costs of litigation and expansion into new markets.

If Uber stayed with their original model and hadn’t gone after global domination, the picture would different. If they stayed with major metropolitan markets and focused on solving a real problem where there was unmet market demand for better transportation options, we might be having a different conversation.

Uber is solving a real issue in major metropolitan areas of the US. There are too many cab companies, they lack digital integration, there are too many unknown factors for someone who needs a ride (who do I call? How long will it take?)

If it’s Friday night, raining, and demand is peaking – there’s no reason why someone with a functional and clean vehicle who is willing provide transportation for someone in need shouldn’t be able to open up an app and find a fare. Having a centralized dispatch such as the Uber app is crucial in places like San Francisco where there are 10 cab companies and it’s hassle looking one up, ordering service and playing a guessing game as to how long it will take to get there.

The problem Uber solves is very real, I think their delusions of ubiquity drove excessive investment and irrational exuberance for being the next Facebook. They should have stuck with doing the one thing that was making the business model work – providing value to a market that was willing to pay for it.

Agree – Uber enables the supply of cars to rise and fall with demand over time. This means there are fewer unproductive cars and drivers out burning fuel and depreciating during low demand periods and more cars available during peak demand. This means drivers have the potential to earn more per hour while also lowering the overall driver cost to the system becasue drivers aren’t sitting around waiting for fares during low demand. Same holds true with depreciation and fuel costs. Riders should be happier because more cars available during peak periods (offset by higher fares charged during peak periods).

In some ways Uber is similar to the (orginal) AirBnb model of matching unused assets (spare bedroom) with demand not met by hotels becasue of cost or availability. To that extent, comparing Uber to taxi company models is like comparing AirBnb to hotel business models – it doesn’t work.

you don’t need Uber to match demand and supply – companies have been doing this for 100 years – with shifts and availability –

the APP allows tighter coordination sure – but coupled with GPS to specifically track the area of the city – the GPS is more important in many ways than the Uber app in terms of D / S Balance – GPS was available years ago with transponders in a car if someone wanted them – check golf carts 15 years ago –

Uber is a glorified dispatcher only – nothing more – a masquerade to investors

must be some sub rosa plan for monopoly with government once in place to control local rules and pay off those politicians to restrict competition

this business should be public governmental entity since the Citizens are paying for roads, cops and traffic control – need to be reimbursed

i disagree. :)

GrabTaxi does this far more efficiently.

Not that driver input will have any effect upon you, but drivers HATE Uber Pool, since the touted better income due to increased ridership has proved to be the opposite. They’ve also found that it creates dissatisfied customers (“One Star For YOU, Driver!”) because of sharing with the “unwashed” and longer rides/missed appointments due to diversions. Comments from people I know who have used Uber Pool? “Never again (accompanied by Stink Face)” and the same person also said she switched back to taxis in San Francisco because of the plethora of non-native San Franciscans driving in order to make the “big money” also don’t know the town and rely too heavily on GPS apps, which are frequently faulty. These are the people who are driving 500 miles round trip, not realizing the wear and tear on their cars, nor the hours it takes to arrive at these locations. It is astonishing. Yet they defend these actions as inconsequential in the scheme of things, but I suspect those who are defending are actually UberShills.

Uber over-saturates the low-income population to gain ridership and that is simply inflating their numbers. But their business model of alienating the wealthier customers will not fly once they have to increase their prices to a profitable level.

Uber is delusional and it’s supporters are in for a rude awakening.

In the absence of the massive scale economies that digital companies enjoy, there is a fundamental contradiction between incurring the cost of providing higher levels of capacity and service quality, and achieving costs low enough to drive incumbents out of the market.

Uber is not a “digital” company, and there is the fundamental contradiction. It disguises itself as a digital company, but operates in the real world, where there is an expense associated with every action.

Digital companies have a marginal production cost approaching zero, and social media companies produce nothing at all, except for presenting eyeballs to advertisers and those advertisers either produce a real world good or are themselves producing a digital good with zero marginal cost.

The shine is coming off the Uber turd.

Exactly, the magical feelings conjured by the digital world have been informing investment since the 2000 bubble. Somehow the perception has been sustained since then despite the contradictions and unsustainable nature of the market being obvious.

The other dissonance is between the infrastructure of society, as maintained by tax payers through the state and federal government and the proposed “innovations” of the tech market. Often these innovations are forced to operate in an environment that is incompatible but they are forced to fit. What comes to mind are driverless vehicles. Ideally, the roads would be built to accommodate driverless vehicles (think in-road visual signals, sensors, etc.) not the other way around (with complex computer vision algorithms, etc.). Similar can be said of Uber, where do vehicles park when not transporting passengers? How are costs absorbed by Uber drivers? Are the costs born sustainable? Likely no, based on Yves analysis. On a more fundamental level, how is road infrastructure maintained. The entire model still hinges on tax dollars to sustain infrastructure, what is time convenient for the customer may need subsidy through other realms of society. Thermodynamics tells us there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Agreed…Uber is about as “digital” as Dominoes Pizza, after all they have an app too, right?

ummm…. 50% of domino’s orders come from online. They are vastly different today than when I used to hang flyers on doors for them…

http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2016/04/21/the-secret-to-dominos-pizza-incs-success.aspx

Are they able to digitize the pizza and send it through the “wires”?

The communication method to order a commodity is different, but the commodity isn’t, so I am not seeing any advances here.

There is still the physical requirement to get the ordered pizza to the correct customer in a reasonable time, and it does not enjoy a digital company’s marginal production cost of almost zero.

Uber can do something taxi/car companies can’t do which is give drivers the ability to work part-time at driver chosen hours. I drove a cab for a while and enjoyed it but you had no option to lease your cab for less than a 8-12 hour shift. Given this and that the number of cabs was fixed, the “market” had no ability to adjust supply or pricing to meet peek demand periods – usually rush hours or during conventions etc.

The incremental/variable cost for a driver to use thier own car is less than a fleet owner’s cost. Depreciation is based in part on usage but mostly on time (e.g. a car decreases substanially in value on the used market every year regardless of usage). If I own my own car, I am already incurring time-based depreciation costs that don’t increase if I choose to drive for Uber a couple of hours a day, So, in some sense there is a cost advantage in the Uber model. It also gives people who are indepently driving for other reasons (e.g. package delivery, coming home from work) the option to possibly earn income from backhaul mileage that otherwise wouldn’t be available.

The Uber model also allows for higher revenue for drivers and Uber at peak hours – something that didn’t exist before. I can see people that have the ability to work flexible hours (e.g. retirees) being willing to drive their cars that are otherwise sitting idle during peak hours rather than greeting shoppers at Wal-mart.

I’m not sure this adds up to change the ultimate outcome for Uber but it doesn’t seem to be apples-to-apples to compare Uber’s model with exisitng taxi companies.

Actually that’s changed and you can now lease a taxicab for just a few hours or for 1-2 days a week.

Flexibility was always there but now most taxi fleets offer same part-time schedule as ride-sharing co’s.

This can be solved with Damians app below, and I’m reminded of a blurb on bbc news the other night (pacific time, I think it was 5am wed. in london) where supposedly ( i say supposedly b/c it was imo another one of those fake news things) where eric schmidt couldn’t solve one of the new hire tests google throws in front of prospective employees called the pirate game. It goes like this, a captain and 10 pirates find 100 gold coins, how does the captain keep the most coins, and longer story shorter the answer is he offers 12 coins to 5 crew to kill the other 5 and gets 40 him/herself. I say that the 5 who are supposed to get killed pick a new leader from their 5, and lets assume the writer of the app that gets rid of uber is the rational choice,, kill the captain and the 5 that were going to kill them, give the new captain the ship (the writer of the app that obliterates uber and who owns the ship/app future income), and keep 20 coins each. It’s just good business. Hey, capitalism, it’s a dirty game ;)…

Wait, Google SERIOUSLY hires people based on how comfortable they are pretend killing their subordinates so they can steal their share of joint profits?

That’s the actual real puzzle?

I’m speechless.

That’s not true. I’m thinking something, but I don’t want to write it down and risk it being used against Yves. Let’s just say I’m picturing carts and angry women knitting, and it seems wholly appropriate.

Just kill the captain and everyone gets 10 gold coins! Seems like the best way to deal with this hypothetical situation to me. I wonder if this theory has any applicability to the real world?

Hahaha.

Adding: Come to think of it I bet it is people who give this answer that Google is trying to screen out with these tests.

That was a part of the long story short, without killing the captain you could just divvy it up, I think it’s just too simple minded mathematically and it’s really a distributional math problem with an ethical angle ala jp morgan while I see it as rational isn’t always that same for all actors and the super genius’ always think everyone else is stupid…at their peril.

Except the problem (if this description is accurate) posits that YOU are the captain. It is your job to keep the bulk of the value for yourself, even though there is no evidence you did anything to deserve this, other than having the title “captain.”

There is no solution I can imagine that isn’t unjust and unequal. That’s the object of the exercise. If you wanted to test people’s math skills, you could construct the problem in other ways. Basically, you kill them, or you get them drunk, steal their guns, and force them to hand over their share to you at gun point. Presumably, you then strand them on a desert island, so they can’t come after you. This isn’t a math problem. It’s a “just how greedy and exploitative can you imagine yourself to be” problem.

Notice how my solution gives more coins to the captain without actually murdering the crew, although it does involve the neoclassical economic tactic of assuming there’s liquor. But why not? Pirates always have liquor around. It a less ridiculous assumption than many Nobel winners have relied on. And it is still unjust and exploitative.

What does it mean that I’m a lefty and came up with a more effective act of greed? (More coins AND I don’t have to worry about any possible murder charges.) Should Google hire me?

The puzzle was poorly described.

You are the captain, and can propose a plan to split the booty. Once you propose the plan, your rational* crew vote on whether to accept the plan. If 50% or more crew vote to accept, then the plan is accepted and implemented. Otherwise you (i.e., the current captain) is killed, the crew chooses the best seaman from their ranks as the new captain, and they do the whole thing over again.

If you proposes equal shares to everyone . . . the rational* thing for everyone to do is vote to reject, kill you, and go forward in exactly the same situation only with fewer men to take an even share. Thus, no sane captain would ever propose this.

The winning strategy was to show the five least capable crew (thus the five last to be chosen as captain) that under any other plan they would not get anything (at best they get nothing, at worst they die), and offer them each one duccat. Being rational, they accept your offer, and you keep the rest.

What I can’t remember is how to show them that they will be stiffed under all other circumstances . . .

* and psychopathic

If it was Amazon the correct answer would be to make all of them work until they die for 1 gold coin a year.

You would be a terrible pirate captain. Assuming the pirates are all rational actors the solution to a 10 pirate/100 coin pirate game would go 96-0-1-0-1-0-1-0-1-0, respectively. To be fair, you don’t seem to have gotten the entire problem/understand the rules as they are traditionally formulated in game theory.

Surely the optimal solution is: 9 coins to each of the ten pirates and 10 coins to the captain.

That satisfies the condition (captain gets the most coins), while minimizing any festering animosities that could undermine the functioning of the crew. Something important in a ship that is likely to encounter combat — what, with them being pirates and all.

If the pirate ship needed less than a captain and ten crew, then I assume that, in the interests of efficiency, they would have eliminated the excess crew before finding the treasure.

Any solution that involves killing part of the crew is short-sighted, since it would leave the pirate ship under-crewed for future encounters.

But then, this is Google. Short-sightedness is one of the key features of the company.

> The incremental/variable cost for a driver to use thier own car is less than a fleet owner’s cost

No. As TFA stated several times, the cost to an individual is higher than for a traditional taxi company which has the advantage of a standardized vehicle fleet. Compare to the individual consumer who has to pay the rack rate on repairs and everything else.

Uber destroys liveable jobs ($13-17/hr) in order to provide a few desperate people with hourly “gigs”, thereby adding to the army of desperate people earning less than minimum wage after all expenses are deducted. Worth it? Not on your life.

The individual is already incurring most of those costs. His or her car is depreciating every day and usually sits idle. He/she may incur higher maintenance costs than a fleet owner, but again, those costs are being borne already. The individual only incurs direct variable costs by driving for Uber (fuel and incremental maintenance) and does not increase the other substantial costs of ownership. It’s very similar to AirBnb’s use of spare bedrooms. The driver’s personal car and individual’s spare bedroom are unused perishable assets – a free lunch to the system if deployed.

I am commenting on the business model and analysis – not seeking to validate or defend the long term impact of these companies in the long run. It does seem worth considering the potential benefits of different models on climate, congestion and individuals ability to monetize unused assets. The issue is really that cost savings and incremental benefit seem to always end up in already deep pockets and that these companies actively seek to undermine state and local governments and regulations that are in place for broader public benefit.

Your waving away higher maintenance costs and physical depreciation of the vehicle would only be valid if you assume someone was driving very infrequently for Uber. I know that’s the pitch to customers, like pretending that their barista is totally cool using their Oberlin degree to make hot drinks. But these articles indicate that Uber targeted professional taxi drivers, knowing that these professionals would offer more value than casual, part-time drivers.

In reality, most people driving will be driving AT LEAST 40 hours a week to make this worth their while. You don’t pick up complete strangers in your own car unless you’re a) serious; b) desperate; or c) both. So this is not like the original/putative AirBnB model at all. A car sitting in a space is not exactly like a car driving people around, because it is driving people around; every moving part is wearing down the entire time the car is moving, plus there is increased risk of physical damage to the car.

You’re doing a variant on “assume a can opener.”

There are variable and incremental costs associated with driving a car. There are also substantial time related depreciation cost associated with ownership. If you buy a new car and only drive it 1000 miles in the first. year it will still be worth. 25-30% less. That is the “spare bedroom” comparison.

Again, you are pretending driving 40 hours a week for Uber won’t put significant wear and tear on the car, and subject it to greatly enhanced risk of damage. There’s a reason the IRS gives you a deduction if you drive your car for work and are not reimbursed by your employer. It is in no way the same as an empty spare bedroom.

Its resale value sinking even if it just sits in a garage is irrelevant. If it’s a new car, and you’re driving for Uber, you are either leasing or paying back your loan. If it’s a lease, its resale value is irrelevant to your financial considerations. If it’s a loan, you want to get more years out of the car after you have paid off the loan. Driving for Uber shrinks that. You are losing non-indebted ownership use of the car. If the revenues produced are great enough, it’s worth it. But that’s not the Uber business model for its drivers. It needs to further exploit them to profit.

Either way, it is not comparable to something going from sitting empty to delivering a profit stream without deterioration and loss of intrinsic value. It is the opposite of that.

I was taking a cab last week on a rainy and windy weeknight and the cabbie remarked that he was going to end his shift early because the fares were far and in between. So it appears that cab drivers are not universally forced to drive for a full shift regardless of demand.

Good points, Tim.

Combine your points 1 and 2, and you also have another reason that the capital cost analysis by Horan is flawed.

The only way that a traditional taxi fleet can put more taxis on the road at peak times is by bearing the full capital cost of the taxis even if they’re sitting around unneeded for most of the week.

If some Uber drivers own a car anyway and only drive a few hours per week – focusing on peak times because of surge pricing – it’s a way to increase the fleet size at peak demand without needing to bear the full capital cost of the vehicle.

There’s a fundamental mistake by Horan in assuming that 100% of the capital cost of every Uber driver’s car should be attributed to providing Uber service. It doesn’t make sense if some of those drivers are going to own cars anyway.

What this article doesn’t address, as well as all MSM, is that the average Uber driver that doesn’t live in one of the above-mentioned LARGE cities, doesn’t make anywhere near that much money. It is more like $6-8 per hour BEFORE depreciation and other costs. It is beyond infuriating when the powers that be, who seem to be at least trying to expose Uber for what it really is (the word monopoly comes to mind, but I’m no expert there), focus on the cities with the most business.

Also, unwilling to examine the likelihood that the higher proportion of “minimum fares” net the driver closer to 50% of the income, with Uber lopping off the “safe rider/booking fee” plus their 25%. I pray that some regulator eventually audits Uber’s books to see what they truly are charging the customers and comparing it to what they assert they are sending the driver’s way. I’ve heard reports that the two numbers are quite different and calls for drivers to ask their passengers to share their eventual Uber fees for comparison.

In short, I would make far more money being a Walmart greeter and wouldn’t have my livelihood held hostage by a star rating system that excoriates me for every four star rating and God forbid the dreaded one star!

Yes, I’m a senior citizen and I’ve applied everywhere, but am limited by my ability to work around fluorescent light because I get migraines from them (hence, no Walmart job).

Am I right in presuming that comparable firms, like Lyft, exhibit a similar lack of economic justification?

What is baffling so far is that Uber is actually externalizing its costs — capital risk to drivers, operating costs to capital backers — and still does not manage to become profitable. Other industries that manage to externalize part of the economic burden of doing business (e.g. not caring about pollution, off-loading third-party liability to the State, getting subsidies for land, power or training, etc) do manage to be profitable. In this respect, Uber looks like a stupendously massive mis-allocation of resources.

Oh sure, stupid on the economics — but that’s not the point. The point is the grift. Uber’s execs make out like deified bandits and Kalanick was at one point referring to his company as “boober” because of “all the tail he gets since running it” (source). Why should the C-suite care if the company is a waste of investment capital when the personal rewards are so great?

Drivers prefer Lyft over Uber, but it is also painfully slow compared to Uber since they don’t have the never-ending supply of $$$ from investors to offset costs. I am heartened by Lyft’s recent advertisements skewering Uber and I hope they further promote their benefits/play to their strengths, instead of continuing to over-saturate certain markets just to get feet on the curb. What I’m trying to say the nature of this service simply isn’t something everyone can afford, and should it be?

As I’ve driven into dense apartment complexes, picking up people at their door who would normally walk out to the curb to ride a bus, asking myself whether or not this is realistic. It isn’t. There is no way on earth charging someone to ride in a car the same amount they would pay riding the bus is economical, nor environmental responsible.

If in any event Uber is able to assume transportation responsibilities on a large scale for lower income America, who do you think will end up subsidizing it? The taxpayer. Good luck with that.

Seems that Uber has a few things going for it. An ap that many people have installed, a name they can remember and they can use it everywhere they go. Seems like all they have is a dispatch service. Seems like the profitably way to run the business would be to charge taxi companies a very small fee (somewhat lower than dispatch and cc fees) and operate as a dispatch company instead recreating existing infrastructure.

yeah but that’s not what they’re doing, maybe you should write that program yourself. My ungrounded suspicion is that the losing side in the election recently held had a plan to shovel gov money into the self driving car thing by painting road stripes legible to autonomous vehicles, I remember vaguely that they promised some really surprising big idea they had to boost the economy that they were going to unveil after the election….all is not lost though since obama lost our chance to kill goldman with fire now they are back in the wheelhouse and free stuff for themselves being how they loft themselves to such great heights I imagine that the idea is still there somewhere…winners and losers and all…hey the seahawks are playing next sunday, wanna go to the game, they won so it should be fun….

Very true – this business whether Lyft or Uber et al – is merely a dispatcher gone digital –

the attempt to take rentier profits by Uber will fail.

This model will revert to essentially a Cooperative (“COOP”) of Medallion Owners with the economy of scale associated with: insurance / maintenance / acquisition of vehicles / use of vehicles 24 / 7 by multiple drivers and the Dispatcher APP used for $1.50 per ride.

The $1.50 will cover software maintenance which is nominal cost once APP is in place for single API – very low cost to write and maintain.

The COOP model with limited Medallions to make sure the vehicles meet safety standards and the drivers earn decent living is “inevitable” – cities like NYC don’t want excess yellow cabs for variety of credible reasons unrelated to monopoly.

So what is $1.50 / per ride all in for the “SOFTWARE BUSINESS MODEL” worth in NYC – present value that cash flow stream less minimal maintenance for the software and you have enterprise value for that market. The Medallion owners have capital necessary to write the APP – and deploy and then put out royalty for other markets to the Medallion owners in SF /LA / HK / London etc –

Or -The NY MTA (Metropolitan Transit Authority) can easily write and distribute the APP and offer a discount to the subway for say ten cab rides and quickly get traction for use and economies of scale for “The Big Apple Taxi MTA” – the $1.50 would go to reducing either the MTA budget or additional services (new trolley routes for example in Red Hook to Williamsburg) so the public gets the benefit of the “streets” which the “public” is maintaining for UBER now (for free -???).

The Medallion Owners and the cabbies then have a decent living and NYC now has a Bus / Subway / Taxi system integrated !

More than 18 years ago i was involved in an APP that aggregated a specific transaction market online with disparate 10’s of thousands of locations and interface to multiple different local software programs with single API interface……… It was not expensive to write nor maintain – operated in seconds with accurate data each time.

Uber is selling a pig in a poke to its investors – I thought Blackstone was involved as investor how could they not understand the business?

good thinking thanks, and blackstone does understand the biz, it’s all about getting gov to cover their posteriors in silk at the expense of the public

Won’t these margin costs be taken care of by 1. Electric vehicles and 2. The elimination of driver fees with self driving cars

This is Ubers endgame

you still need humans to service cars. unless you want your next Robo-car to smell like a 1995 London telephone booth.

(many) People are messy/filthy–even seemingly respectable bourgeoisie types. (citation—experience as an ex-Uber driver or just look at the piles of garbage left behind by people in economy and first-class on your next flight)

and you still don’t solve the dead-heading miles problem as robo-cars can’t just park on the curb after stopping someone off at Rockefeller Center.

That end game is a long way off. Meanwhile, they need to crush all the medallion companies so that desperate drivers will work for slave wages, the way Amazon exploits its warehouse workers.

But I don’t see how that’s going to work either. Breaking regulatory regimes in cities will benefit its competition, too. As soon as it has a monopoly and crushes its drivers, it should be pretty easy for a competing app to launch with no big investors to feed or global branding to manage. Advertise on mobile social media to raise customer awareness. This would be a perfect worker co-op opportunity. Management isn’t needed at all. They don’t seem to be offering any real value to workers or customers.

And Uber needs to crush its medallion competition completely, not partly, like Amazon has, and utterly drive them out of business, because as long as the medallions exist, Uber can’t slash worker compensation enough to stop bleeding red ink. So: they need to keep losing money for a really long time, completely driving their traditional competition out of business in EVERY major city they operate in, and then get people to drive for them for slave wages, while those drivers still maintain their cars in appealing enough shape to protect the Uber brand and enable the professional class it targets as customers to feel good about using the service. And they’re doing all this just to tread water in terms of cash flow, while they wait for both significant technological advances AND an enormous outlay of government funding and regulation in every country Uber operates in to install and maintain new and sophisticated infrastructure necessary for self-driving vehicles. In the United States, neither major party seems inclined to spend money on far more basic infrastructure. I realize Silicon Valley thought it had bought the government when it bought Hillary, but do you really see the current Congress (which, after all, is the one Hillary was trying to engineer for herself) actually spending that kind of money? I believe all Trump is offering is tax credits, and he was elected explicitly promising infrastructure. I suppose they could do some sweet repatriation deal where Apple, et al. uncover all the cash they’ve been hiding with no tax penalty if they spend their money on the self-driving car infrastructure. But all these companies could be spending their money to build their businesses. They choose not to. They like to take free government money to fuel their business models and tuck their profits away.

And that’s yet another layer of complication. That’s more lobbying costs, to get the government to cut them the exploitative deal they seek. And it has to be replicated, to some degree, in numerous countries, with numerous governmental structures and numerous cultures.

I was a History and Literature major in school, but I know a scam when I see one. This is not a business model. This is a long con. I understand it superficially resembles Amazon, but there are numerous crucial differences, like how Uber can’t hide its abused workers from its customers and isn’t investing in things like warehouses and complex supplier chains that create significant barriers to competition. This is a bit like the Clinton campaign. She shouldn’t have won, because all the structural elements pointed to the change agent winning. We were supposed to ignore that, because Clinton had so much money, and so many institutional advantages. And yet, despite all that, she didn’t win. History hasn’t ended. You can’t mix subprime mortgages with prime ones and treat them as one asset class forever. Eventually, fundamental reality wins. Uber is trying to build a global monopoly, but it doesn’t actually control or offer anything vitally necessary. Anyone with a car and Google Maps can pick people up and drive them somewhere. There are already ride-calling apps out there. The rest is just marketing, unless or until radical technological innovations and massive government expenditures facilitate self-driving cars — but they’d better be bullet-proof, because the hoards of impoverished Americans left without income in a world in which the government funds self-driving cars by not universal health care, or higher education, or a jobs guarantee will be pretty mad. And they’ll have lovely targets to express their feelings, conveniently driving around in presumably branded vehicles, with no one inside but the perpetrators of the crime against them.

I see a lot of parked cars during the day. Isn’t using some of that depreciating capital, by bringing in part time drivers, the justification for any efficiency improvement arguments?

When cars are parked, they’re not incurring much costs. When used for Uber, you’re just shortening a car’s 20 year lifespan into a few years. In fact, with the dead miles needed to travel to the next paying customer or where a customer cancels before you get there, it’s less efficient.

The cars may be parked but the drivers aren’t! The only way that argument holds up is if e.g. when I park my car I give access to it to someone else to use as a quasi taxi service for a few hours.

The solution to the parked car problem has been known for a while (150yrs+) – trains & buses & trams aka public transport.

This series is important evidence, if more were needed, that Naked Capitalism is a powerful voice for truth. Uber not only loses on the financials but they have aggressively sought to establish monopolies and degrade public transportation. Even if we wanted to accept a monopolist we should ask ourselves if Uber can be trusted in this role. The evidence says no.

Uber has a history of attacking journalists who merely report the truth about their company.

Uber has a pattern of victim-blaming riders who are attacked by their drivers.

Uber has a history of seeking to distort the media narrative about them through underhanded means.

You know what other company this reminds me of? Theranos, another moral and financial failure.

Uber fails on economics and fails on ethics. Thank you to NC for having the courage to report the truth.

Let’s say Uber does somehow succeed in transitioning to a fully self-driving fleet? Does that really alter their cost structure that much. Instead of paying drivers, they now have to buy and maintain a vehicle fleet themselves? And if they want to maintain the standard of on-demand service within minutes of any big city location, having enough vehicles to do that would seem to be more expensive than having a small army of part-time drivers who don’t pull in more than a few thousand a year. Could a self-driving fleet actually end up costing Uber more?

Why do people keep repeating this? They take people from point A to B in cars, but not “like traditional car operators always have”. Name me a service operating before 2010 that had smartphone integration, reliable, tip-free service, actual responsiveness to complaints, and which was willing to drive you to far-out places, and which had mutual rating to weed out bad drivers/passengers. Or one before 2014 that had on-demand carpooling.

. . .They take people from point A to B in cars, but not “like traditional car operators always have”.

Traditionally, they were called taxis, and the taxi operators were called “cabbies” and in the old days, when a cabbie gave a customer a rough ride, a call to the dispatcher by the customer would land the cabbie at the bottom of the call order list, waiting a loooong time for the next fare, and gasping for money to pay the daily rate. Cab companies even had their own communications infrastructure in the form of 100 foot tall aerials and radios in every car, so not even cell phones, never mind smart phones, but so what? That got the jawb done, which was pick up your fare and take them to where they want to go, the further the better.

Go ahead and believe the whole Uber turd is worth 15 Nimitz class aircraft carriers, after they only invested in three and then sunk a few to gain “market share”. The Fed works in mysterious ways, and before you know it, the finance flim flam artists will have sold it to you.

Very good piece. Another neo-liberal “success story” exposed as a Potemkin village scam that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. Regarding Uber’s driver compensation claims… I had the feeling the “our drivers earn $90k/year” thing was aimed primarily at customers, rather than at potential employees, er, “independent contractors”. Or maybe I am overestimating how many shits the average Uber user gives about using a service that engages in exploitative labor practices.

That inflated income claim certainly helps the rider feel justified to not tip the driver who is providing a service. The driver, who also believing the “thousands a week” claim, bought a car (lol, guilty) not realizing at the same time they were driving their car into the ground with every passenger. A passenger, for instance, who scrapes gooey black mud off their shoe onto the door jamb while exiting, barely acknowledging the offense and not even apologizing. Or the abysmal way certain people treat the drivers, to the point of soul-sucking angst… Many instances such as these are why I “cherry pick” my rides and avoid certain areas of town, as do all riders who have a clue.

The nicer people I do target, some are indeed delightful, most are very pleasant and a scant few (usually drunk and belligerent) one-star me and I one-star them. But the dreaded conversation many bring up, “how do you like driving for Uber” cannot be answered honestly. I do enjoy the interaction with the people, but they’ve been primed to expect a free water, candy, and gum with every ride and when my $6 per hour before deductions doesn’t really allow for that expense, they probably give me a four-star rating. Which is not good. So, when I am honest and explain the economics in detail, the response is often “Well, at least you’re making SOMETHING.” What those people are telling me is my time is not worth diddly-squat.

They have no clue that if Uber prevails, they will be forced to pay more for this service. Karma at work.

$69B would buy a lot of high speed train infrastructure……….

13BN not as much, but ubers backer’s would be unlikely to favour a large physical product with generally low returns when they harbour the dream that they just might see a share of that imaginary 69bn for doing very little.

Izabella Kaminska Article in Financial Times Praises Huber Horan and Nakedcapitalism.

The taxi unicorn’s new clothes

https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/12/01/2180647/the-taxi-unicorns-new-clothes/

With a name like Kaminska, she must be one of Putin’s stooges

In the first article and again here, you state that consumers are only paying 41% of the cost of their trip. “Uber has grown because consumers have been choosing the company that only makes them pay 41% of the cost of their trip; there is no evidence that taxi customers in a competitive market would pay more than twice as much for the service quality advantages Uber investors have been subsidizing.”

As I see the numbers, Uber is only retaining money equal to 41% of their costs. But the amount that consumers pay is the sum of what Uber keeps and what the driver keeps. So assuming a 75/25 split of a passenger dollar; the $0.25 needs to be increased to $0.61 for Uber to break even. They could increase the total fare rate by 36% and shift the driver/uber split to 55/45 to accomplish this. So the passenger would have to pay 36% more for Uber to break even without decreasing net driver pay per mile. I am not claiming that a 37% fare increase would not decrease usage; but it is much more plausible than asserting that consumers would have to pay more than twice as much for Uber to break even.