Yves here. This post is simultaneously informative and frustrating. I first discussed the corporate savings glut in 2005, and co-authored a New York Times op-ed about it in 2010. As I wrote in 2010:

Rob Parenteau and I have an op-ed at the New York Times today. Rob’s last post here argued energetically that the now-established trend of the corporate sector to save, as opposed to invest in growth, in advanced economies, and even most emerging economies, was tantamount to capitalists abandoning their traditional role. It reminded me of an article I had written in 2005, “The Incredible Shrinking Corporation,” for the Conference Board’s magazine Across the Board, on how companies were trying to starve themselves into attractive- looking performance though the then-unprecedented act of saving in a time of economic expansion, which is tantamount to disinvestment. Rob’s post made further key points about the macroeconomic implications of corporate savings (given the norm of households savings as well) and made some policy recommendations….The draft was titled “It’s the Corporate Savings Glut, Stupid! The Hysteria of Marching to Austeria”:

On the one hand, the VoxEU article does a fine job of assembling long-term data on a global basis. It demonstrates that the corporate savings glut is long standing and that is has been accompanied by a decline in personal savings.

However, it fails to depict what an unnatural state of affairs this is. The corporate sector as a whole in non-recessionary times ought to be net spending, as in borrowing and investing in growth. As a market-savvy buddy put it, “If a company isn’t investing in the business of its business, why should I?” I attributed the corporate savings trend in the US as a result of the fixation of quarterly earnings, which sources such as McKinsey partners with a broad view of the firms’ projects were telling me was killing investment (any investment will have an income statement impact too, such as planning, marketing, design, and start up expenses). This post, by contrast, treats this development as lacking in any agency. Labor share of GDP dropped and savings rose. They attribute that to lower interest rates over time. They again fail to see that as the result of power dynamics and political choices.

You’ll observe that the rise in corporate savings corresponds to the start of the neoliberal era, roughly when Reagan and Thatcher took office. That is also when central bankers became more preoccupied with fighting inflation than promoting full employment, as a result of continuing to fight the last war of beating the 1970s stagflation (as well as becoming hostage to the ideology of the day). That meant central banks were explicitly in the business of weakening labor bargaining power by increasing the size of the reserve force of unemployed workers. The result was a long term tend of falling Treasury interest rates, which broke in May 2007, and stagnation of real wages as businesses captured the benefits of productivity growth, which had formerly been shared with laborers.

By Peter Chen, Loukas Karabarbounis,Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Minnesota and Brent Neiman, Professor of Economics at Booth School of Business, University of Chicago. Originally published at VoxEU

In the aftermath of the Global Crisis, economists and policymakers have been concerned that the pace of global recovery is constrained by the saving behaviour of firms and households. For example, Carney (2012) expresses concerns that the improvement in private-sector balance sheets is related to elevated uncertainty and lower spending, hiring, and capital investment. Alfaro et al. (2016) argue that, in an environment with financial frictions, the increase in uncertainty delays hiring and investment decisions and instead leads firms to hoard cash and reduce their debt positions.

In a new paper, we characterise patterns of sectoral saving and investment for a large set of countries over the past three decades (Chen et al. 2017). Consistent with previous studies such as Poterba (1987), we measure the flow of corporate saving from the national income and product accounts as undistributed corporate profits. Corporate saving together with government and household saving equal national saving.

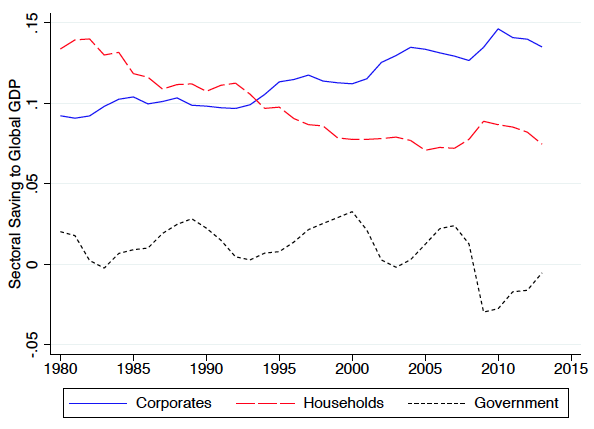

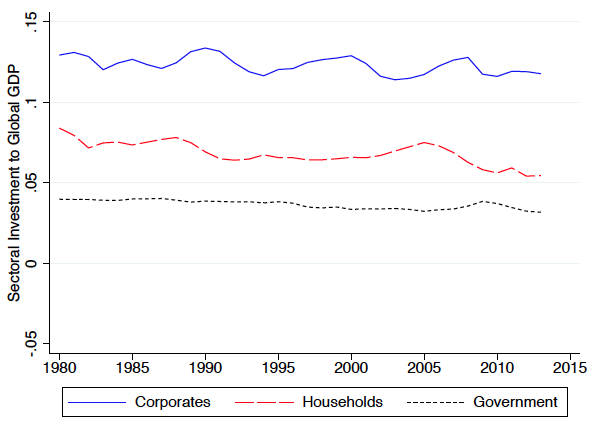

Figure 1 Global sectoral saving and investment trends

We find a global shift in the composition of saving away from the household sector and toward the corporate sector. The top panel of Figure 1 shows corporate, household, and government saving as a fraction of global GDP. Global corporate saving has risen from roughly 9% of global GDP in 1980 to almost 14% in 2015. Household saving has also exhibited a dramatic change but of the opposite sign, leaving the global total saving rate relatively constant. The bottom panel shows that, unlike saving, the sectoral composition of investment has been relatively stable over time. The corporate sector transitioned from a net borrower to a net lender of funds to the rest of the global economy. Contrary to common belief, this rise of corporate saving significantly predates the Global Crisis.

Using national accounts data, we find that corporate saving increased in the majority of countries, including all ten of the largest economies in the world. Using firm-level data, we find that corporate saving and corporate net lending increased in the majority of industries. We do not find evidence that trends in firm saving relate significantly to firm age or size. Increases in corporate saving within industry and types of firms, rather than shifts of economic activity between groups, account for the majority of the global rise in corporate saving. Taken together, our results suggest that the rise of corporate saving is a pervasive phenomenon and it is unlikely to reflect structural changes (e.g. the decline in manufacturing), idiosyncratic changes of particular firms or industries, or changes in corporate financial practices in particular firms or countries.

Corporate saving is undistributed (accounting) profits, or equivalently the part of corporate value added (or corporate GDP) that is not paid to taxes, to labour, to debt holders, or to equity holders. Using national accounts data, we document that taxes, interest payments, and dividends have remained essentially constant over time as a share of global GDP. Using firm-level data, we show that firms with larger increases in their (accounting) profits experienced larger increases in their saving rates but were not significantly different in their tax, dividend, or interest payments. The rise of corporate saving, therefore, emerged as the decline in the labour share pushed up corporate profits and dividend growth did not keep pace.1

How might multinational activity impact the rise of corporate saving? A multinational company’s saving is attributed to the country of its headquarters. Therefore, if production shifts to countries other than the headquarters, those countries’ measured corporate saving rates will be affected. One benefit of studying the rise of corporate saving in a dataset with many countries is that, to the extent that it is representative of the world economy, any such cross-country reshuffling of value added by multinationals should cancel out at the global level. Multinationals might also play an important role in driving the rise of corporate saving, given their (tax-driven) incentive and ability to shift profits across countries. We cannot precisely identify multinationals in our data, but we find that firms with significant income from foreign operations have indeed exhibited a larger trend increase in their saving rates than firms without significant foreign income. This larger trend increase in saving, however, comes from a larger trend increase in firm profits and not from differential changes in tax or dividend payments.

An increase in the flow of corporate saving relative to expenditures on physical investment implies an improvement in the net lending position of the corporate sector. How were these additional resources used? Among other possibilities, firms can buy back their shares, pay down their debt, and accumulate cash or other financial assets. Using firm-level data, we document that the balance sheet adjustment involved all three of these categories. However, we find interesting differences over time. Increases in firm net lending were more likely to be stockpiled as cash starting in the early 2000s, and were less likely to be used to buy back shares after the crisis.

Our analysis highlights that the proximate cause of the rise of corporate saving was the combination of a declining global labour share, and the stability of the dividend share of output. What might have been the deeper forces underlying these trends? We develop a model in which capital market imperfections such as dividend taxes, costs to raising equity, and debt constraints affect the flow of funds between corporations and households. We parameterise the model to represent the global economy in the early 1980s and feed into it changes in components of the cost of capital that we measure from the data – such as the declines in the real interest rate, corporate income taxes, and the price of investment goods – alongside an increase in firm markups and the slowdown of growth observed after the Great Recession. Our model generates a rise of corporate saving and a decline in household saving similar in magnitude to those observed in the data. The decline in the cost of capital and the increase in firm markups led to a decline in labour’s share and an increase in accounting profits. Given the stickiness of dividend payments, these additional resources were retained within the corporate sector rather than paid back to shareholders.

See original post for references

In the first half of the 80s, it was impossible for corporations to do an ROI calculation and come up with a positive figure. Interest rates were higher than what any legal investment in plant & equipment could yield. So the rational biz choice was to save it. Plus, Japanese Invasion in our home markets. We were learning to share, too.

So…it’s totally awesome to see that corporations continued in increase savings as percent of global GDP steadily since then.

Huh? The rise in savings means they are not investing. Companies don’t need savings beyond enough working capital to keep operating and a bit of a rainy day buffer. There’s no need or justification for a 5% increase relative to global GDP.

Your view is US centric. This article is about global savings. Even as of the early 1980s, Japan and Germany were investment powerhouses and neither was suffering from high inflation. Germany’s was in the 4-5% range, which is below where it had been in the later 1960s and early 1970s, and Japan similarly had its big inflation spike before 1970. Its inflation rate was down from 25% then to ~5% in 1980. The US was roughly 25% of world GDP then as now.

World inflation looked high, but most of Latin America was awash in very high inflation (rates over 50%), so that would push the averages up.

And even in the US, I had clients at Goldman who issuing bonds at 13-15% to make investments. There was no “legal” constraint. Despite high inflation in most key countries, investment then was 26% of global GDP in 1980 versus 25% in 2015.

Gotta use sarc tags….I was trying to signal the part after “totally awesome…” as sarc.

Yes, I did share two of my jobs with the global savings rate in the early 80s. I finally found a place to gainfully hide in Reagan’s defense budget.

This is also why I’m single handedly pushing to get our sectorial balances to be much more granular when looking at economic sectors. Nowadays, I think the pharma and healthcare industries are “saving” a lot, but other industries, not so much.

Aren’t these Corps using those ‘savings’ in buy backs, issue junk bonds and M&A, activities?

What about the record level US Corporate debt being mentioned?

And this is the point. Surplus capital in face of surplus labor. This is how capitalism works. Why would a company that has its mission only profit invest in growth when in a rentier society they are able to make their profits by sitting on the golden egg?

And debt is simply a supplement for low and shrinking wages and jobs. This gives the illusion that the economy is working, that capitalism is benefiting people when in fact it is debt servitude and no jobs or precarious ones.

Capitalism is the problem. Any socioeconomic system that puts profit before people will find a way for their rulers to do just that.

As technology replaces more and more workers under the current economic system of ruination, this will mean more crisis, more disposable popualtions,more war and more poverty and inequality.

It is time to stop debating these issues within the confines of the capitalist debate. Capitalism simply is a failure and cannot provide jobs, dignity,moral values or the material and subjective conditions for an honest good life.

“… and a bit of a rainy day buffer.”

G7 + China private non-financial sector debt as a percentage of GDP increased exponentially since the 80s until the mid-late 2000s, reaching an average of 160% of GDP, then it plateaued and it is now stable or falling (all of this happened much faster in Japan). So the corporate saving glut can be explained in large measure by corporations making preparations for a very long rainy season ahead as the debt grew. They were not doing the investing it is expected of them just because the return on the investment could not be proved with sufficient certainty to be higher than expected interest payments on the globally raising debt in their environment (their clients and the economy at large). Central planners have been trying hard to convince corporations that interest rates will be low for a very long time (thus the observation in the posted article that interest payments have remained a constant fraction of GDP) but with everybody’s debt rising fantastically (until the mid-late 2000s) who you gotta believe, central planner promises or the bulging volume of debt growing everywhere around you?

Your stats include household debt, which is not a valid part of the computation. A big part of the neoliberal paradigm was to use access to debt to substitute for wage gains so that consumers would have the appearance of rising standards of living in the face of stagnant wages.

Moreover, Andrew Haldane and others have documented that companies use discount rates that are well above their cost of capital and/or a project-appropriate discount rate, when they should be using one or another. Your claim regarding inability to meet their ROI is thus spurious.

Yes my stats include households as well as non financial corporations and this seems valid to me because the point is that the environment of corporations (which include both households and other non-financial corporations as the clients of corporations) is not conducive to invest, this environment was and is way too much indebted to spend surpluses in investment (much less borrow to invest).

Don’t you think that a 160% of GDP of private non-financial debt would dis-encourage investment by surplus-making non-financial corps (in spite of any individual project discount rate and cost of capital) or at least be a major factor weighting on decisions whether to invest or save?

You want to think it is short-termism which is also possible of course, I guess it would be ideal to find an environment with exponentially increasing debt and quarterly earning reporting versus another environment with exponentially increasing debt and longer term earning reporting, ceteris paribus.

except we arent at 160% of GDP (GDP being some where around 20 trillion a year. now if we want take the longer view (which is how we get a bigger number than GDP) and thats based on forecasts (basically a guess) as to what will happen (out to 20-50 years. when we have trouble with forecasting out a day or week), its gets ridiculous to even try to guess what it will be. and it usually exclude the yearly GDP too till that future date (the 70 trillion debt ‘forecast’ that depends on heaping 70 years of forecasting. and its usually done very pessimistically too.

what is discouraging them is the lack of current demand. its just not there. and that they are their own worst enemy for causing it, just gets glossed over

Yves, IMO good article selection on your part. It seems to me that a fair meta-reading of it would take us to learn that a strict money supply fetishism leaves what is primordial unscrutinized.

Absolutely. And with Trump,for the US, calling for repatriation of capital with a tax incentive we can see if this takes place what will happen. More savings for corporations and less investment.

But this is how capitalism or this stage of financial capitalism must work. Why would I,as a corporation,invest if I can do mergers and acquisitions and keep stock prices artificially high and bonuses high?

And this is the point: the slow decay of capitalism means that even the capitalists do not wish to take risks, invest.

The system seems to be dying, digging its own grave as Marx noted, but it is resilient — make no mistake about it.

On a daily basis, I am hearing executives talk about growth targets while their managers focus on cutting costs. I think the current management generation has forgotten or never learned how to grow revenue. Part of it may be that increasing revenue requires “risky” investment that may not work out whereas you can always get an immediate improvement to the bottom line by cutting another cost. Getting a “Go” to proceed in responding to a client’s RFP takes endless meetings and conference calls that use up half the time available to do the proposal. It is much easier for a manager to disapprove the cost of responding to an RFP than incurring the “cost”. The next staff meeting then has an exhortation to go out and get more work to meet targets.

I think this is more of a symptom of the problem than the problem itself. If CEOs don’t expect robust economic growth, their incentives to invest are lowered. If wages aren’t growing, it’s hard to have robust economic growth. In a high-functioning economy, capital investment would be accompanied by demand for more/better-paid labor, so you get a pickup in both supply and demand. In our economy, however, capital is capturing all the gains, so wages and hence demand don’t grow, and you just get overcapacity. So it makes sense not to invest, narrowly.

That’s exactly right – why should a company invest in expanding production capacity if they can’t sell what they’re currently producing. This is a symptom of declining real income among the general population – and a shift away from mass production of consumer goods.

Example: should automobile manufacturers invest in plant expansion if they can’t sell all the cars they’ve currently produced?

Correct! Profits first regardless of growth.

Another reason for high corporate savings is likely the unrepatriated profits held in ‘tax haven’ entities to defer paying U.S. corporate tax. U.S. Companies can’t use any of this sequestered money for capital expenditure or acquisitions until they pay these taxes. I think the current estimate for this money is between $1.6 to $2.1 trillion. Here’s a helpful guide to the biggest offenders:

http://ftp.workingamerica.org/Corporate-Watch/Paywatch-2016/Tax-Avoiders#

This is also a reason why companies with plenty of cash issue bonds to fund now ubiquitous share buybacks.

maybe. but its not like those rates have changed. but as some one mentioned earlier, if the business isnt investing themselves, why should any one else? they dont are showing that they dont believe in their own business, why should investors?

and even while they arent repatriating over seas profits, its not like they arent being held in US banks. and the last time we gave business a tax break to ‘bring’ the money home, it didnt nothing for the businesses (they bought shares instead of investing in the businesses)

At least with one public company I am familiar with, it has apparently used unrepatriated profits to make FOREIGN acquisitions of two companies in Europe.

It still avoided paying US taxes on the money and expanded the overall company via the foreign acquisitions.

I wonder what MBA school makes of this. Isn’t sitting on your cash the equivalent of taking the “going concern” principle of business and breaking it over your knee? These are C-level executives looking at the economy for the past ten years and deciding that nope, there’s no money out there to be made, there’s too much risk, so we’d better just become the world’s most poorly-managed hedge fund.

What is Apple’s return on its billions of parked dollars?

The Economist called them out on this, for crying out loud.

Another way of looking at the fixation on quarterly earnings is that it is symptomatic of profound risk adversity.

When you’re focused on what is more or less the most granular reading on an institution’s finances (quarterly reports), as opposed to less quantifiable measures (R&D tracks), you’re inevitably hyperventilating over the temporary ups and downs.

I know it’s kind of stating the obvious, but I think we should confront the risk aversion aspect of it, along with the greed.

Simple explanation – rise of the bureaucrat! As long as you dont make ANY decision, but you can align yourself with good decisions and wag the finger at those who took risk and failed, you win. Every day you dont make a decision at a corp or govt agency, you’re one day closer to a juicy pension and won’t get fired.

Its the ” I didnt make the rules” but only abide by them strategy. I’ve seen it many, many times. Of course, it also hollows out all real innovation but who cares? We got ZIRP, lawyers and CPAs!

As we all know Apple aren’t just world leaders in consumer technology they are also outstanding in the field of starving stagnating economies that enrich them of much needed investment.

These multinational magpies hide behind the apparent respectability of fiduciary duty in order to justify their obscene, fiercely damaging, obsessive hoarding, but ultimately they are a constant reminder that we live in the age of corporate fascism.

Another woeful example of what defines and differentiates ‘globalisation’ from ‘global trade’ and that highlights the abject failure, reluctance and/or failure of governments of any and every hue across the world to address this ongoing iniquity.

The once relatively virtuous circle of capitalism has become ever more vicious, and it currently appears that there isn’t anyone, anything, anywhere that will, or more pointedly can do a damn thing about it.

Corporations do not invest, becaus they do not expect to see enough profit from their investment.

Many of them could easily increase the output without further investment – but there is no buyer.

maybe you shoul read “WORLD CRISIS: ROBERT KURZ’S ANNOTATED INTERVIEW by CHARLES ODEVAN XAVIER”.

Robert Kurz is a German philosopher and historian, anchored in Karl Marx. Sorry for that.

or – as is stated on your site in the link “U.S. Car Demand Collapse Jeopardizes Trump’s Auto Factory Push” –

“The swerve in consumer taste is just one of the forces — along with slumping used-car values and a pullback in subprime auto lending — that are changing the equation for manufacturers as President Donald Trump leans on the industry to build new plants and boost hiring. That’ll be hard to pull off: A glut of both new and used vehicles on the market has sparked an incentives battle, meaning new production lines are the last thing the companies need.”

well slumping used car prices might be because the price of used cars had sky rocketed as so many wouldnt buy new cars (the national sales rate went from over 13 million a year to less than 10 million. a lot less. and in some cases those used car prices were almost as much as new ones. just had higher interest rates

And with the growth of surplus labor throughout the world there will be little consumption without debt. As technology is in the hands of the ruling elite any improvements in technology that could improve our live will be sacrificed on the altar of Ayn Rand.

Without a change in the way we produce and reproduce our lives, technology will become our enemy.

So I think we see the problem – greed.

Translating the above quotes, corporations have all this extra cash because the C-suite decided to stop paying workers and keep the money for themselves.

The article doesn’t go into household savings but perhaps the reason we aren’t seeing increased household spending is because households haven’t received increased wages. Kind of a no-brainer. And IIRC from other articles, economists consider paying down debt to be the equivalent of saving for households so my guess is that individuals aren’t really saving (what’s the point with ZIRP?), by trying to get out from under the massive debt they incurred in order to stay afloat in an era of stagnant wages.

This isn’t going to change until we take the money away from these crooks and redistribute it.

Raise corporate taxes.

It solves everything.

New New Deal. It’s long past time.

In other words, they are sitting on cash.

Apart from stock buybacks, which I’m sure are timed with executives exercising stock options (see http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-buybacks-pay/).

The problem is that while in the long run, investors may not be harmed, it is bad for society. It means that C-level executives can cash in. Also, rather than invest in something productive, they either sit on cash or use it to boost executive compensation.

Also there seems to be a strongly negative correlation between 1980 to 2008 for corporation savings and household. Could it be that wage suppression from corporations has led to the point where households simply do not have the money to save?

I think the problem is in the Risk : Reward ecosystem.

At least since 2008 – with ZIRP – the Federal Reserve changed the natural order of the economic universe by implementing a ZERO Interest Rate (or nearly) policy. Zero Interest Rates effectively tell the saving and investing public – there is NO Risk. No risk, exemplified by Too Big To Fail, Government comes to the Rescue for all necessary events… No Risk changes everything. It misallocates capital away from the highest return – to other places. Fundamentally – interest rates do 2 things. First they ENCOURAGE CAUTION to lenders, based on borrower and investment risk. Secondly, they REWARD CHANCE – because there WILL BE winners and losers – and the spoils go to the victor. That’s a free market economy. Simply – the government ZIRP policies have ruined the economics of lending and investing. If there are no spoils, why would a business invest?

not sure that 0 interest rates do that, cause if you look at what customers see, they dont see many 0 interest rate loans except for special deals. and if business isnt investing in it self, they dont need money, so even if Fed hadnt lowered rates, they wouldnt have driven rates up. so bonds wouldnt have grown. and since consumers wages havent gone up, they need to higher savings rate but lower loan rates. which cant happen. and banks dont have much demand for money, or savings rates would be higher. and they havent been all that high for decades.

why would a business invest in itself? because they need to increase profits by making more sales. but since demand is low (mainly cause the consumer hasnt had a raise in decades) they dont see a need to.

and by the way, even if the Feds had set rates higher, it wouldnt have matter. demand would have collapsed even more. since low income consumers buy less when rates are higher leading to less demand

The global corporate savings glut is not a sign of corporations abandoning their role in investments. It is a sigh that there are no investments to be made that fall into the risk/reward profiles these corporations are expected to seek. This is a sort of chicken and egg situation. The reason there are no investments is because consumers have no money to support the outputs from these investments, and the reason for that is AUSTERITY. The world’ governments MUST boost spending to provide this additional purchasing power on the part of consumers. This brain dead idea, cooked up by Milton Friedman in the 60s and popularized in the 70s, that national budgets must be balanced is nothing more than the gold standard disguise by eliminating the gold. We are in a world-wide gold standard recession/depression, and it will not end until we stop this right wing crap about “sensible” national spending policies. Governments create money — all of it — and right now, we need more of it in consumers’ hands, and that means more money in workers’ paychecks.

Government deficit is exactly equal to the penny (hey, I’m English) to that of the private surplus.

All that ‘saved’ money, be it off or on shore, is cumulatively a ticking time bomb unless spent, repatriated by investment or through taxation, particularly in terms of inflation.

Venal, myopic politicians have tacitly encouraged and allowed big business to adopt an increasingly parasitic model, gorge itself on its hosts and hoard its rewards for far too long under the premise (and promise) of wealth creation and the constant empty threat of plying their trade elsewhere, leaving the debt/money creation system as we know it stretched to the max and possibly broken beyond repair.

Even the state’s magic money tree has its limits.

I agree with lyman alpha blob: The decline in wages means a decline in household savings, which implies that corporations are now looting personal savings, too. In the U S of A, which has had low personal savings rates, you now see a debt-ridden middle class. As Hannah Arendt pointed out, wealth means property, assets like a paid-off house or land. The U.S. middle class doesn’t have wealth. It has debt.

Meanwhile, this is rich:

“capital market imperfections such as dividend taxes”

My immediate response is, Then raise the tax rates. If the supposedly free market has imperfections (may the market gods avert their eyes), then let’s raise taxes to get some revenue and reshaping of the market out of it. (And “capital market imperfections” also strikes me as a typically Chicago Boothian mealy-mouthed formulation for Friedmanian fundamentalism.)

And why even allow stock buybacks? Why would they ever be in the best interest of a company that is profitable? For the vanity of the “named executives”? (You can tell that it is proxy season, and as the owner of a few IRAs and SEPs, I have just voted my 103.7 HP Enterprise stocks–against the foolishness.)

On the other hand, at least these three were willing to “go there.” They have shown themselves to be B-school heretics with an article like this, I s’pose.

There is no savings glut, global, corporate or otherwise! There is global dollar debt glut and money is just one type of debt in the system. Of course there appears to be too much money/savings in the system because people don’t truly understand money. So called money is created when banks make loans and we live in a world drowning in debt which means it is drowning in money as well. This is a paradoxical and confusing point but true nonetheless. The debt and money get separated after creation, with the debt being widely dispersed as a general rule and the money more highly concentrated which confuses the issue for most people. And American companies don’t pay much, if any tax, which also adds to this issue. If they did they wouldn’t haves so much of this so called money.

The fundamental issue here is an explosion of debt and money over the last 30 years and how it has been distributed. Someday this will be properly understood and seen for what it is. The greatest scams in human history.

indeed.

the hint is the debt to GDP ratio,

As the debt to GDP ratio has exploded, there is nowhere for that extra money to go. Hence we have exploding asset prices.

Basically it makes more sense to invest in financial assets (esp property) than in production.

all thanks to fake money.

yes the Debt/GDP ratio says it all.

Financial capitalism is the system now. Not industrial capitalism and yes, it is one of the biggest three card Monty scams ever to have existed.

continued

There will be no return to normal in a world economy swamped in debt. That is the legacy of the great era of bubble finance. It pyramided up assets prices and buried the economy under a mountain of debt and rentier claims associated with those inflated prices. The natural outcome of this should have been a brutal deflationary collapse which would have cleansed the system but that of course was unacceptable. The financial engineers at the central banks kicked the can down the road by ginning up a bunch of new accounting entries that delayed the day of reckoning, but it is still out there.

Well put!

DEBT has been a universal panacea for all the financial problems, all across the globe both Public & private!

All of them are at record levels since 2009! Housing bubble is back to it’s previous peak, Sub-Prime auto credit loans with inclreasing defaults and of course ever increasing student DEBT!

What could go wrong?

Your comment is spot-on. We are at, or very close to, the point of the polar equivalent of 1989 just before the collapse of communism and the chaos that followed . When our bubble economies in the west collapse as surely they will there will be chaos and it won’t be pretty .

With growing unemployment debt is the only thing that keeps many people alive — including the holders.

But this is all unsustainable. The only question is when it will burst the next time. Crisis is the essence of capitalism. This means the creation of crisis as well through war, debt,etc.

well war predated capitalism by a millenniums . but t certainly has learned how to profit from it

I guess this came along a bit later but I worked for a company that jumped into Six Sigma big time when I got there it was only two people working in the whole building but there were pictures on the wall from the 80’s. An office full of smiling faces, having picnics together, salespeople with secretaries, multiple warehouse staff, they had pensions and two week vacations etc.

Flash forward to more or less the present day and it’s me and one other guy with salespeople that work from home, no secretaries, and my boss told me I would cap out in pay after a year or so and then they would replace me.

Occasionally some ghoul would come in from New Jersey to give us more bad news.

I think they call it “lean” not sure if that is an acronym or a description of how they squeeze labor.

Corporations are saving for retirement.

;) ;) ;)

I’ve got to agree. Raise corporate taxes.

Further, the implications would unstick personal debt to reignite the housing market which is slumping in major countries.

Until then, second chance finance will continue to be a growing speciality need http://fortressfunding.com.au/what-is-a-second-chance-loan/

Corporate savings are not put in a pocket, they are used to make more paper assets.

Large amounts of “pump priming” leveraged “paper assets” are backing the gambling in the crooked financial market.

I say gambling as it would be for you or I but we do not know the answer to the important questions. What is the amount of money you need to steal before you are not prosecuted for criminal activity and how do you do it. They are counting on the “too big to jail axiom”.

This money is not savings risk free as an individual would define savings but put in multiple high risk “banks” that use funds for a risky high return. It has been some time for me but look at the sources and uses of “finds and/orv liquidity” if it detailed enough. P.S. the term cash is so undescriptive.

Why would companies invest? Because of low rates, the ageing of the population, the pension structure based on funding and promoting an ever larger weight in equities, the money is flowing in no matter what…

Not to mention that ageing investors are increasingly looking for the perceived security of blue chips.

Right, which is one reason why capitalism does not work for the majority and in fact robs them of life.

So the companies won’t invest in growth any more. So where do they put their money? With the present low interest policy, are there any good alternatives?

Even if they give the money to shareholders and higher executives via buybacks etc., won’t those have the same problem? Of course they can buy art and other curiosities, but how much impact can that have?

buying their own stock seems to be the answer

Demand was the driver all along, companies won’t invest unless they see the demand there.

“Supply creates its own demand” was something Say said, but no one believes him apart from economists.

“Global corporate saving has risen from roughly 9% of global GDP in 1980 to almost 14% in 2015. Household saving has also exhibited a dramatic change but of the opposite sign, leaving the global total saving rate relatively constant.”

That suggests some equilibrating process.

“The bottom panel shows that, unlike saving, the sectoral composition of investment has been relatively stable over time. The corporate sector transitioned from a net borrower to a net lender of funds to the rest of the global economy. Contrary to common belief, this rise of corporate saving significantly predates the Global Crisis.”

Hmmm. The corporate sector transitioned fro a net borrower to a net lender. Does that indicate a trend towards neo-feudalism? Households kowtowing to corporations just to survive? Can you spell debt peonage, boys and girls?

It all comes down to my maxim “What part of no freakin’ customers do you not understand?”

If the efficiencies of automation, cost savings of outsourcing jobs, and unfair tilting of the market toward corporate interests decimate the buying power of your customers, what is there left to invest in?

Corporations aren’t investing in satisfying the needs of an increasing customer base exactly because their prior actions have shrunk the customer base below the break even point of the capacity they already have.

Wouldn’t it be rather insane to invest in more production capacity when you already have too much, and are shutting down some of what you already have?

I just can’t understand why economists are searching to find more trees while they are standing in the middle of a forest.

If you’ll go back and reread the article, you’ll see that this trend did not coincide with the onset of automation or outsourcing.

The reason economists, if this is what one wants to all them are searching for trees is because their ideas have the breadth of monkeys. There are no economists that are not paid for in the world, or few let me say. The majority are bleacher cheerleaders for the ruling elite.

>corporate savings glut< all over the world?

There is one big exception: China

Have a look at this data (pick "China" and "Corporate")

https://data.oecd.org/natincome/net-lending-borrowing-by-sector.htm

Up to the big crash we had the same trend in China as in the West,

but since 2007 the corpations are borrowing and they invest, so its no

miracle that the growingrate is much higher …