By Georgios Petropoulos joined Bruegel as a visiting fellow in November 2015, and he has been a resident fellow since April 2016. Georgios has extensive research experience from holding visiting positions at the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, Banque de France in Paris and the research department of Hewlett-Packard in Palo Alto. Originally published at Bruegel.

In my previous blog on artificial intelligence (AI), I dealt with the general characteristics of AI and machine learning. Thanks to complex virtual learning techniques, machines are now able to perform a wide range of physical and cognitive tasks. And the efficiency and accuracy of their work is expected to increase as AI systems advance through machine learning, big data and increased computational power.

The benefits are clear, but there are also concerns for the future of human work and employment. If indeed machines continue to improve their performance beyond human levels, a natural question to ask is whether machines will put humans’ jobs at risk and reduce employment. Such a concern is not new but in fact dates back to the 1930s, when John Maynard Keynes postulated his “technological unemployment” theory.

In general, automation affects employment in two opposing ways:

- Negatively – by directly displacing workers from tasks they were previously performing (displacement effect)

- Positively – by increasing the demand for labour in other industries or jobs that arise due to automation (productivity effect)

So, the real question is which of the two effects will dominate in the AI era. Before we deal with this question, let’s travel back in time to previous industrial revolutions. Some interesting case studies are reported by The Economist:

- During the 19th century, the amount of coarse cloth a single weaver in America could produce in an hour increased by a factor of 50, while the amount of labour required per yard of cloth fell by 98%. However, the result was that cloth became cheaper, and demand for it increased. This created four times more jobs in the long run.

- The introduction of automobiles in daily life led to a decline in horse-related jobs. However, new industries emerged resulting in a positive impact on employment. It was not only that the automobile industry itself grew fast, increasing the available jobs in the sector. Jobs were also created in different sectors because of the growing number of vehicles on the roads. For example, new jobs were created in the motel and fast-food industries that arose to serve motorists and truck drivers.

So, past cases suggest that in the short run the displacement effect may dominate. But, in the longer run, when markets and society are fully adapted to major automation shocks, the productivity effect can dominate and lead to a positive impact on employment.

The invention of cars and automatic looms was long ago, but the Economist article also presents similar case studies of more recent technological developments.

- The introduction of software capable of analysing large volumes of legal documents reduced the cost of search but increased demand for it. As a result, the number of legal clerks (who before the implementation of the software had to search for the legal documents manually in a more time consuming way) increased by 1.1% on average per year between 2000 and 2013 instead of decreasing due to the displacement effect.

- Automated teller machines (ATMs) might have been expected to significantly reduce the number of bank clerks by taking over some of their routine tasks. Indeed, in the USA their average number fell from 20 per branch in 1988 to 13 in 2004. But that also reduced the cost of running a bank branch, allowing banks to open more branches in response to customer demand. The number of urban bank branches rose by 43% over the same period, so the total number of employees increased.

So, even in more recent examples, we see that technology leads to new employment opportunities in a way that we could not even imagine few decades ago. The automation of shopping through e-commerce, along with more accurate recommendations, encourages people to buy more and has increased overall employment in retail. (The annual growth of e-commerce in Europe is 22%. See Marcus and Petropoulos, 2016 for relevant statistics and policy discussion.) People can also generate income by supplying services on collaborative economy platforms where the entry barriers are very low. And people can further utilise available assets in an efficient way through the supply-demand matching algorithms in place.

Should we expect that the impact of AI on employment to follow similar patterns? Perhaps not. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that, compared with the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, AI’s disruption of society is happening ten times faster and at 300 times the scale. That means roughly 3000 times the impact. This very fast technological progress in the AI era raises the question: Is this time different?

Nevertheless, it is difficult to answer this question in a clear and convincing way. Reviewing recent research and economic analyses we see that there is no consensus on the impact of automation on employment.

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) deal with industrial robots (“an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, and multipurpose [machine]”) which perform tasks like welding, painting, assembling, handling materials, or packaging. Thus machines that “have a unique purpose, cannot be reprogrammed to perform other tasks, and/or require a human operator” do not fall in this definition of industrial robots.

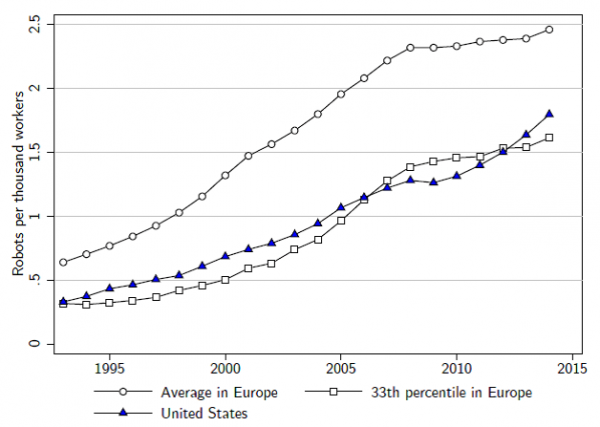

Using data from the International Federation of Robotics about industrial robots in the post-1990 era, the authors report that Europe has introduced more robots in its labour market than the US. In European countries, robot usage started near 0.6 robots per thousand workers in the early 1990s and increased rapidly to 2.6 robots per thousand workers in the late 2000s. In the US, robot usage is lower but follows a similar trend; it started near 0.4 robots per thousand workers in the early 1990s and increased rapidly to 1.4 robots per thousand workers in the late 2000s. In fact, the US trends are closely mirrored by the 35th percentile of robot usage among the European countries.

Source: Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017)

The authors conclude that one additional robot per thousand workers reduces the US employment-to-population ratio by about 0.18-0.34% and wages by 0.25-0.5%. The industry most affected by automation is manufacturing. However, interestingly, they only find a weak correlation between the increase of industrial robots and the decline of routine jobs.

When we are trying to interpret these results we should not forget that there are still few industrial robots in the US economy. If the spread of robots proceeds over the next two decades as expected by experts, such as Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2012) and Ford (2015), its aggregate implications for employment will be much larger. These books also warn that “white collar” jobs could be impacted just as much as “blue collar” ones.

Frey and Osborne (2013) predict that about 47% of total US employment is vulnerable to automation over the next 20 years. In contrast to the books mentioned above, the authors of this study also suggest that new advances in technology will primarily damage low-skill, low-wage workers as tasks previously hard to computerise in the service sector become vulnerable to technological advance. Bowles (2014) repeated Frey and Osborne’s empirical exercise for Europe, concluding that 54% of European jobs are at risk because of automation.

Chui, Manyika and Miremadi (2015) estimate that 45% of work activities could be automated using already demonstrated technology. If AI systems were to reach the median level of human performance, an additional 13% of work activities in the US economy could be automated. The study also finds that even the highest-paid occupations in the economy, such as financial managers, physicians, and senior executives, including CEOs, have a significant amount of activity that can be automated.

There are also studies that find a much smaller displacement effect of automation on employment. Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn (2016) predict that on average across the 21 OECD countries, only 9% of jobs are automatable. Atkinson (2016) agrees with this estimate, looking at the next 20 years, as he said at a recent Bruegel event about AI.

The big difference between this 9% estimate and 47% reported by Frey and Osborne (2013) is explained as follows: Frey and Osborne focus on whole occupations rather than single job-tasks (occupation based approach) when they estimate the risk of automation. Even if some occupations are labeled as high-risk occupations, they may still contain a substantial share of tasks that are hard to automate. In contrast, Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn adopt a task-based approach which focuses on the risk of specific tasks to be automated . That dramatically reduces the estimated impact of automation.

This makes clear that a crucial point when assessing the impact of automation is to determine what will be technologically feasible in the next decades and how capable the machines will be in replacing humans in their job tasks. Manyika et al (2017) estimate that only a fraction of less than 5% of tasks consist of activities that are 100% automatable, suggesting that a task-based approach can better capture the impact of automation. They also report that about 60% of occupations have at least 30% of their activities that are automatable.

All these studies have focused on the displacement effect of automation. What is even more challenging is to try to also assess the impact of the productivity effect. That would require predicting future market developments based on exact assumptions about the creation of new occupations, industries and tasks facilitated by new technologies that have not yet arrived. This is extremely hard to do! Who would have thought 20 years ago that with smartphones we would be able to perform many different tasks on one device, and that there would be huge new markets related to their function?

Even industry experts seem to be divided over the impact of automation on employment. Smith and Anderson (2014) asked 1900 experts in the field about the impact of AI on employment by 2025. Half (48%) envision a future in which robots and digital agents will have displaced significant numbers of both blue- and white-collar workers—with many expressing concern that this will lead to vast increases in income inequality, masses of people who are effectively unemployable, and breakdowns in social order. The other half of (52%) expects that technology will not displace more jobs than it creates by 2025.

There are also voices which claim that automation will not have any impact. Bob Gordon, for example, trying to explain mediocre US productivity growth concludes that “the benefits of the digital revolution were over by 2005” and that AI will only have a very limited impact. On the other side, the world-famous physicist Stephen Hawking goes several steps further by predicting that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.” The debate is broad, to say the least.

The fact that it is difficult to predict the exact impact of AI makes it complex to frame a policy response. But some society-level reaction is surely needed. It is therefore necessary to initiate an open consultation of all involved parties, to define our approach towards the AI era. This process will have several steps.

- The first important step is to understand what AI is and what its potential will be.

- Then, we need to define a framework of rules for the operation of machines and AI automated systems. These must go far beyond Asimov’s famous three laws of robotics. The Civil Law Rules on Robotics proposed by the European Parliament can also motivate social dialogue about issues related to liability, safety, security and privacy in the coming AI era. Adopting clear rules based on a good understanding of this new era could make the transition easier and mitigate potential concerns. However, adopting rules without good understanding and knowledge of how this new technology will be implemented (first step) would be be counterproductive.

- As a third step we need to design and implement those policies that will help us to accommodate new technology possibilities. For example, one way to move forward could be to carefully redesign education and training programs so that they provide the right qualifications for workers to interact and work efficiently alongside machines. This might minimise potential displacement concerns. Such initiatives will require the close interaction of authorities and institutions with major technological firms which have both the know-how and the capacity to contribute to the training. Improved instruments for job search assistance and job reallocation could also be beneficial and would mitigate concerns associated to the displacement effect. Without any doubt the Partnership on AI of the big high-tech companies can help promote the needed social dialogue and coordinate further developments with the participation of multicultural research groups and educational institutions.

At the moment we are far from a political consensus about the challenges of the AI era. The US Treasury Secretary Steve Munchin does not seem concerned at all about the impact of automation on employment. This position clearly contradicts the previous US administration, which even published a comprehensive report about the challenges of the AI era (considering employment one of the main worries). Christine Lagarde, in her talk at the Bruegel/IMF event shortly ahead of the 2017 IMF Spring Meetings, identified the impact of automation on employment as a concern that requires policy actions.

However, we should not rush into a response. The time for policy will come, but at the moment we are still at the first step of understanding the potential of AI and that various ways is might impact on our economy. To deepen this understanding, we should further promote social dialogue among all the involved parties (researchers, policy makers, industry representatives, politicians, etc). This is a vital first step to better grasp the challenges and opportunities of this new industrial revolution. And although we should not rush to conclusions, we must also act swiftly. The speed with which technology advances may introduce disruptive forces in the market earlier than some people might think.

AI is still quite a long way from the versatility and dexterity of humans in handling materials and assemblies, and this is likely to remain true for a long time.

Automation has less effect upon worker displacement than outsourcing to less developed nations, because poor workers are cheaper and far more versatile than robots. This will continue for several generations as Africa and other areas replace present sources of low wage labor. Then rising wages may gradually raise prices of manufactured and processed goods.

The increasing use of ordinary machines and power tools in developing nations may have more effect than automation in developed nations.

Indeed, well said. I point out again that we have had the ability to make automated shirt-sewing machines for decades, but most clothing is still sewn by hand by 50-cents an hour labor because of the much lower capital, maintenance and risk costs. The cost of electronic gadgets is falling, but the cost of industrial-grade electromechanical systems that can perform sustained work for years is NOT falling. Cars are not getting cheaper, nor are airplanes, trucks, industrial grade milling machines, etc. It’s not just the capability, but the total lifecycle cost.

Although I question the author’s sources (imagine citing The Economist, whose statistics can never be verified, and hence never responded to any of my challenges over many years, and the McKinsey Global Institute, which profited mightily from their jobs-offshoring practice, and aided in the offshoring of millions of American jobs) — I do actually agree with the thesis as the programming and coding together with existing hardware has progressed to the point where few are aware of just how commonplace and mundane AI advances have become.

I’m afraid for our future . . .

John B wrote: AI is still quite a long way from the versatility and dexterity of humans in handling materials and assemblies, and this is likely to remain true for a long time.

At an MIT conference on AI a month ago, I saw the next-gen algorithms and mechanical grasper-picker limbs that are going into Amazon warehouses and other companies’ factories over the next couple of years.

In controlled environments like warehouses and factories — as opposed to a fully human mobile worker doing a job like a plumber’s out in the field (but you did say manufacturing and assembly) — I wouldn’t say your claim is likely to hold true for as long as you may assume.

A lot depends on costs, of course, vis a vis human labor.

Yes, graspers and pickers for warehouses and very simple assemblies are already viable, but cannot handle even the simplest ordinary snafus, like two units stuck together, something that doesn’t quite fit, etc, etc. The pseudo-AI people at MIT have been sounding this horn continuously for sixty years and are not much closer to replacing the assembly worker, because the tasks are just not as simple as they wish and pretend.

I spent some years at MIT trying to convince them to study intelligence and not simulations, but there was no money in it. Their funding comes from military targeting, where they classify “collateral” innocents as “terrorists” to cover their inability to distinguish, and from data searching, which is ordinary software, not artificial intelligence. Otherwise they program arms with little ability and call it intelligence, to make themselves feel better and pretend to know something about intelligence. That’s where they will stay.

Basically this.

The current “modern” trends in machine learning for example are “nothing else” than applied math (most of it very old, some of it centuries old) techniques, specially statistics and linear algebra, some of it (a lot) with poorly understood statistical properties (in case of “neural networks” which btw have not much in common with how real neurons work, nevertheless networks of neurons).

It all makes it sound like magic with a few marketing tricks and buzzwords, but when you get to the core of it there is not really much fundamental advance.

However, this does NOT negate that there is a trend in automation due to increasing ENGINEERING efforts. Again, in the ML field for example, the production and extension of well engineered software and widespread access to good quality libraries and teaching material (the fundamental maths behind it), as well as increasing interest in the field will increase an adoption and automation of certain amount of tasks where data digest and analysis in needed.

Why? Because machines do it better, that’s why. But it did not take a revolution in “AI” for us to know that, is just that the engineering effort to propagate the necessary changes was not happening sufficiently, but with the current infrastructure (both in hardware and software) and manpower (of both software and hardware engineers) it can happen (slowly, but can happen).

So it’s possible we will see an other wave of automation (already happening) both for mechanical works in semi-structured environments and in data digestion, analysis and decision support (which will target a lot of mid to low level white collar jobs during the next decades).

The ATM / Branch example is polluted by the fact that banks opened a percentage of what they call limited service branches. They are deliberately smaller branches. I know of several near me where there are no lobby just a single drive up window with a single employee.

On the other hand, to carry that example further banks are currently on a branch closing spree because of internet banking. With the ability to deposit checks via your smartphone there is less need for a branch.

Having a smart phone makes you a slave of the Deep State. I avoid it for that reason. If the only way I can do banking in the future, is with a smart phone, I will be going off-net.

Excellent comments — and B of A just recently opened three full-automated (no humans employed) branches . . .

How is it possible to have an informed discussion about a thing, AI, that does not exist without engaging in fear mongering and useless speculating? First, I believe, we must humbly admit that Artificial Intelligence does not exist yet and that the use of that phrase reflects more an aspirational research program than the reality. What exists are various types of neural network mechanisms and flavors of automata that have very little in common with how our brain functions but ape some very limited aspect of human intellect using various mathematical theories of how such things might work.

I find it hard to get too worried about getting replaced by an AI in the near future considering most human activities draw simultaneously on a vast number of different mental abilities that we are consciously unaware of and each particular one difficult to replicate with even the most advanced neural network which once trained is no good for anything else. One-shot-learning that we do effortlessly is still a matter of research in AI. Things that appear simple are extremely difficult and hard things turn out to be simple so engaging in speculation where we might be in a year let alone decades is fraught. I read a few years ago that a new sewing machine using a trained neural network with a model of how seamstress do their sewing had successfully replicated human sewing which does not suffer from the artifacts that kept automatic sewing machines from the taking the market so we might expect sweatshops in southeast Asia to dwindle. And yet they have not.

What I see happening now is a variety of digital assistive devices emerging that cut down on the amount of effort of repetitive mental tasks and that learn our individual preferences when we do such tasks. For instance, a neural network might be trained to maintain the comment section of Naked Capitalism but that wouldn’t replace Lambert since he provides additional value that an NN cannot provide. Those new devices tend to be virtual or entirely digital without any physical component because once you create a brand new device and start impacting the physical environment your costs, and liabilities, become large. The internet-of-things is just adding a digital interface grafted (grifted) onto dumb devices already in common use, like your fridge, so automata can be programed to operate it to your needs. You are not creating a new device that is removing a function previously done by a person. So the end product for now might be improved quality of life if those devices are seamless and nearly invisible because once they require attention all the benefit is removed by the mental cost to us. Assistive driving devices will take over for us on long distance road trips but will defer to us on poorly maintained or crowded roads with aggressive traffic so a driver is still needed.

Artificial General Intelligence is what all of us think of first of when AI is mentioned. It is nowhere in the horizon right now unless some massive discovery happens on the scale of a Newton or an Einstein. It requires naturalizing epistemology, a deep understanding of how we know things and what it means which is a field philosophers have muddled for at least two millennia and needs a modern scientific treatment. Since the brain accomplishes it, it must be achievable and we appear to be approaching the question from both top-down, meaning using our knowledge of the theory of computation and other theories, and bottom-up, using our knowledge of neuroscience, molecular biology and biophysics. My guess is they might meet in the middle with one path informing the other. So because the vast amounts of cash entering the field the participants are not humble or honest about what they have achieved and what they see on the horizon and that is polluting the discussion.

Finally, the second important point is we must be more humble about the unaided human brain capacity. It is not all that. The same way the Earth is not the center of the Universe, the human brain is not the best brain possible. There are some good reasons to believe that human brain capacity is far short of full Turing-computable systems. A successful AGI would not be so limited. And THAT is scary.

Where do self-driving cars (likely long haul trucks only on interstate highways first) fit in on this?

Are they AI?

Automation is real, AI is not. AI is a marketing scam to cover certain kinds of automation. Not every form of automation works, or is economical. Long haul autonomous trucks will work, because all private cars will be banned from the Interstate, to help fight terrorism.

AI is real, and has already been deployed for some time. Hell, even video games offer some form of “AI”. What doesn’t exist is the kind of “AI” that is being speculated about in studies such as this one.

This form of AI is basically human intelligence and ingenuity without all that pesky free will and other human failing such as demanding to be paid. Let’s call it what it is slave/automata.

I completely agree with you here that slave/automata doesn’t exist and is largely the product of the neo-liberal imagination, the “perfect worker”, a laborer that has 100% (or greater) productivity, cost nothing and produces no waste.

Self-driving cars are very much AI.

The question that we should be more bothered by is what kind of AI — i.e. to what extent we achieve effective self-driving AI by relying on deep learning techniques that are more or less black boxes, in that we know they work effectively 99.999 percent of the time but we don’t know how they work effectively, which in turns means we don’t really know under what circumstances they’re vulnerable to failure

That is an interesting conundrum…we take cabs everyday or drive with strangers and frequently we don’t know their failure modes either…did they drink recently for instance…the many ways humans can fail are stupendous and yet there we go on our merry way taking a cab to the airport or home…

Yes, it is crucial to find out how such automata can fail but we have to be honest with ourselves and accept outside some low hanging fruit we will never know the full picture, only that however they fail it will be differently than HOW human beings fail and that is the core of why we find it so disturbing even though automata will likely fail so much less than a human driver in similar driving conditions. When the gentleman from Texas riding his Tesla got driven under a truck that to a human being was plainly in the middle of the road the mind rebelled at such computerized idiocy but other equally disturbing failures are probably on the menu.

I used to believe such until a few years back when I observed the Eureqa program in action . . .

Look into fast.ai some time and their deep learning programs.

(And one might also check out: ThinkNear, Telenav, SnipSnap, Affectiva, Emstient, ShopperTrak, FaceFirst, Tapad, BlueKai, eXelate, Euclid, First Data Corporation (an old standby in the financial surveillance and vote manipulation biz), Vibes, and DeepField Networks.)

I agree that AI is not quite here yet, but I believe it’s closer than you seem to think. That in fact, it’s right on our doorstep. What do I have to support that? Not much, so take it with how ever many grains of salt you like, but.. I see signs.

And when I say AI, I mean machines that can reason and learn, and are self aware, like in the movies.

Why would you need a machine that is self-aware? It is pure anthropomorphism to presume that AI can’t have the abilities to reason and learn without consciousness.

In fact, AI can and does have the capability to reason and learn (to increasingly effective values of reasoning and learning) without consciousness.

In fact, AI no more needs consciousness than a fish needs a bicycle. (Setting aside the engineering difficulties.)

You may be right. The assumption I am making is not so much that consciousness is a precondition of learning and reasoning, but that consciousness will arise from those processes at some point. It’s a bit of a leap either way, I fully admit.

AIs need a form of consciousness in order to be self-monitoring, at multiple levels. Without it they will be fragile and prone to failure, unable to achieve a high-level of autonomy. But you’re right that it won’t closely resemble human consciousness.

@ MoiAussie —

Well, AIs perhaps need both self-monitoring and agency – the capability to formulate objectives – at some point, to some precisely limited extent (since we don’t want Bostrom-type singletons).

But I don’t see that those things necessarily translate further into either qualia or some machine equivalent of ego — and of course we’re very, very far away from figuring out the former, anyway.

If you’re interested, it’s clarifying to spend some time reading some neuroscience because the neuroscientists actually have more clues than most people realize about why we ourselves have developed consciousness.

To be reductive, consciousness is not some majestic emergent property of sufficient intelligence (i.e. of human intelligence as opposed to animal intelligence) but seems to be an evolutionary kluge to get around the limitations of meat neurons doing electrochemical signaling when no neuron can exceed speeds of 100 hz.

Given those limited neuronal speeds, evolution’s problem was how to bind the whole brain together so the organism could operate in real time. (In other words, we’re back to William James’s binding problem, though not as he framed it.) This isn’t a problem that electronic AIs running on a silicon substrate have to deal with.

These two neuroscientists in particular have offered accounts of consciousness that I find plausible (as far as they go). YMMV, of course —

Rodolfo Llinás at NYU School of Medicine —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodolfo_Llinás

Llinas has a book called I of the Vortex: From Neurons to Self that’s a good discussion of the issues, IMO.

Ezequiel Morsella, who’s the director of the Action and Consciousness Lab at SFSU —

http://online.sfsu.edu/morsella/people.html

One should be cautious here. Isn’t it an assumption that “human consciousness” even exists? We could be computer simulations for all we know. Or for that mater, the human brain is just another form of computer.

This has been a question that has vexed philosophers for centuries without resolution. I am rather skeptical when technologists say that computers can or can not achieve consciousness when the concept itself remained to be properly defined.

What is really being said here is that computers can never be human or achieve “human consciousness.” This is a bit like saying humans will never achieve canine-consciousness..

What is called “AI” is merely programming of cool simulations; this has kept it “on our doorstep” for three generations with no fundamental progress. The hype doesn’t even get them funding, because there is no economic value in real artificial intelligence. All of the funding is military targeting and database search, which are completely unrelated. The researchers have no interest at all in real intelligence, merely in using the term “AI” to pretend to know something about intelligence. They don’t, and they don’t want to know.

Agreed, none of the hype has anything to do with AI but peddling the stocks or attract new VC funding rounds.

Monte Carlo iterative method? Pattern matching. Object recognition? Linear predictive filtering? Genetic Algorithm? Neural networks?

All of them are “damn, brute force solutions” to mathematical problems that cannot be generally solved analytically as Trump would say, “beautifully”, so massive computer powers are unleashed not really any intelligence.

Nothing, what we could call “intelligence” is in it except for human intelligence of whoever wrote the code.

The AI in previous naive understanding (as replacing human decisions) is a Dead End and even DARPA admitted that, after thousands of project they funded over last 50 years often inspired by futuristic authors.

The problem is that engineers have been fed wrong or simplistic concept what learning is and what intelligence is, both concepts in the center of currently unsettled philosophical discourse.

One of these issues they are struggling with is misunderstanding that abilities of highly trained individuals such as pianists, soldiers, chess or Go players, F1 drivers, artisans, etc, are not because they are using “intelligence” to solve problems they face during performance.

Those actions do not exemplify human intelligence, they are just loaded with massive b-tree type context memory database of possible use-cases they experienced or imagined and play instant situation matching game to choose optimum solution without necessity of any conscientious thought.

In fact if human intelligence or intuition exists it is most likely used in the process of creative inception of new concepts by synthesizing perception of the environment or new concepts created abstractly in our mind in order to shape how we think not as much of what we think.

May be true intelligence is ability to recognize and realize the way we think about the world, not our ability to understand what is the world in itself.

In other words, perhaps human intelligence is an ability to recognize problems, to create them, rather then to find solution for them.

But there is out there understandable social concern about attempts to assign government/social authority or legality of accepted judgments stemming from judgments of so-called AI bots, which would be very dangerous and would amount simply to a fraud since AI is just a Wall Street hype without essence so far but could be easily used as a coercion tool as already FB/G++ using it by rating/flagging some news as fake without any shred of authority of such a judgment.

To prove it realize that NK website was quoted in WaPo last year as part of anti-American conspiracy of Russian spies or useful idiots based supposedly on AI analysis of the articles published on NK site. It was a lie.

What a absurd assignment of authority to a dumb algorithm called AI.

Some people starting to see what is going and it is not going toward producing a slave robot nation under human command and control as we could see in most movies but rather more matrix-like setting of human enslavement by tech savvy oligarchic elites under guise of phony AI robots.

Well said. I have seen no essential progress in “AI” in the forty-five years since I tried to convince those at MIT to study real intelligence instead of fixed knowledge representations. They have no interest in real intelligence, just cool space-man simulation toys used to pretend to know something about intelligence. They have absolutely no funding to research the real thing, just military targeting and database searches, which are unrelated. They have achieved nothing beyond that, and are stuck there indefinitely, largely because intelligence doesn’t pay in the USA.

Intelligence doesn’t pay. I like it. Makes you wonder how much actual intelligence there is on this planet, artificial or not.

“the Earth is not the center of the Universe”

The Universe is Infinite and the Center is Everywhere.

edit: meant as reply to dontknowitall

Excellent article, but…..

I’ve been discussing AI for a long time (no, it really isn’t a new ‘thing’) with my friends and family and I’ve noticed something interesting (to me, at least) …..

My techy friends and family embrace AI and are excited to see where it will lead. I share that view!

My non-techy friends and family are more afraid of it than not and worry about how it will change society, and , yes, I share that view too!

Both are right, but neither sees the other’s point of view – it’s like they are talking past each other when discussing AI. So what is going on here?

As much as I love my techy friends and family, I really don’t want them making societal decisions because they just don’t have a deep understanding of the issues, and as much as I love my non-techy friends and family, I don’t want them making decisions about science because they also don’t have a deep understanding of the issues…..

I think the problem is that our educational systems have become siloed. We don’t educate to make good citizens, we educate to get people employed. People who are in STEM don’t have to take much humanities, and people in humanities don’t have to take much science and math – and that is becoming a really big problem!!! I think the AI debate points that out in a big way.

Yes, all of us need to understand AI, but then all of us need to understand history, philosophy and sociology too, because it’s those fields that will help us decide how to develop AI to more benefit than harm society – and we seem to forget that!

” We don’t educate to make good citizens, we educate to get people

employed. ”

Very sorry to disagree with you here – we educate the elite to get them employed.

We educate the underclasses to get them in debt. And ready to accept that they will have to kill themselves working two jobs just to stay afloat. And then kill themselves off when the illnesses hit. Oh, and just in case any of the latter slip through, we’ll encourage overseas elites to fill any leftover cushy positions. Want to go to college? Get a lottery ticket and you just might be lucky.

It’s not artificial intelligence, by the way, it’s artificial stupidity and cupidity. Writ large and ominous.

To embroider my point:

Artificial intelligence does exist. The prime example is the washing machine. It is artificially intelligent because it lightened my load, and at the time I bought it, I could pay for it without going into debt. That’s artificial intelligence.

Not artificial intelligence is the self-serve cashier in use so many places of retail business. That is stupidity and cupidity combined – stupidity in those who elect to go through the store quickly and not mind the fact they have just put that extra human cashier’s low-paying job in jeopardy. Cupidity because it ultimately profits the store owner or owners in the case of ‘investors’ to employ less people and not have to worry about said individuals not having a living wage. They sleep better, those elites – what’s not to like? Profits + an easy conscience = win/win.

Oh, but of course we all profit in the end because we have more leisure time to pursue that ephemeral college education. (That one is also snark. I guess I got up pretty edgy this morning. Don’t think I’m alone in that.)

Very well articulated . . .

There is no reason to charge for education except to keep the caste system in place. I don’t disagree with you on that. All education should be considered a human right and be free.

But I think you have AI confused with the computer revolution. Automating cashiers is just using computers in place of people, not AI. And the computer revolution is over, done! Perhaps you saw “Hidden Figures”? Do you think NASA still employs human computers?

The author of this article is right – change is happening to us at an ever increasing rate – so fast that humans just cannot keep up – and that is the reason AI is coming. Consider for an instance all the air traffic out of Heathrow or even JFK. Do you think humans could handle that traffic without computers? Now how about if that traffic is doubled as it will be in time. Do you think just number chugging computers will be able to handle it?

What is interesting is that in my father’s time a person with an eighth grade education could get a good job and support a family. When I graduated high school, a person with a high school diploma could get a good job and support a family. In my children’s time, a person needed at least four years of college.

And I’m seeing because of how fast our world is changing, that perhaps four years of college isn’t enough education for a person to be able to understand all there is to know to make the decisions a citizen needs to make……

Consider for instance, the new large corporations like Google and Facebook. Perhaps you can think of times in the past people got rich off of something they got for free and the havoc it created for society? Ex: How do you think plantation owners got rich? Why are we allowing corporations to get rich off of something they take from us without our informed consent and sometimes without our knowledge? Don’t you think that if perhaps we understood those issues in the 90’s, that we wouldn’t have allowed them to do this? Don’t you think that we would insisted on some benefits to society in exchange for our data? Those companies didn’t do this out of thin air – they were all created by techies who learned, usually in college, how to do this. But they never learned how to contemplate whether or not this was a good thing to do. And most of the rest of us didn’t learn what was happening until it was all over…..

If we as a society don’t understand what AI is and how to control it for the benefit of humanity, then we as a society will be in the same position we were in the 90’s and those techies who do understand AI will run over us and take from us things that we don’t even know we are giving away, because they won’t be considering the humanistic reasons as to why they shouldn’t do that. Perhaps we should all be thinking about that instead of slamming something that is coming whether we like it or not?

The problem is that neither the techies nor the humanists are looking at artificial intelligence, just simulation toys that do something that appears to take some kind of understanding. But those toys do not know anything about what they are doing. I have been in this field and know the base problem: no one is working on the problem of intelligence, just specific software problems and space toys, because there is no money in the pure research, just military targeting, database search, and a few primitive manipulators etc.

Perhaps you should do a little “upgrade”? For instance: http://allenai.org/

Paul Allen has lots of money…..and he’s not doing military research……

Besides just automation you should include process changes. Consider the steel industry where in the us it takes 1/5 the labor to make a ton of steel it did in 1950. This is because first of the change from Open Hearth to Basic Oxygen furnaces (cutting production time from 12 hours to 40 mins per heat), then the move to minimills that reuse scrap steel and continuous casting. Or in sawmills where the computer now figures out the optimum way to cut a log to get the max timber out of it.

So process change is as big a factor and automation more than robots so far. I don’t know if one would call a multiaxis CNC machine a robot or just automated. but it has changed machining drastically. (watch how they work on youtube). Then there is the coming 3d printing, which will enable the making of things that could not be made in the past. One use here is to make molds for use in casting.

Or look at the automated pipe handling systems and iron roughnecks in high tech oil drilling, no need for folks to throw chains or topmen to wrestle pipe 100 feet in the air.

So the issue is really automation, and process change and their effect. (In many cases as you automate you also change how the job is done)

Let’s look at where jobs have been created in the last 5 years. Total jobs created about 12 million (2012 to 2017), up 9%. Where?

On the above average upside.

Bars and restaurants 1.6 million up 17%

Health care 2.0 million up 11%

Temp help .5 million, up 22%

Professional and tech services 1.2 million up 15.7%

Warehousing and storage .268 million, up 40%

Couriers and messengers .105 million, up 20%

Construction 1.27 million, up 24%

By contrast:

Manufacturing .4 million, up 4.2 %

Government up .34 millionup 1.5%

Thoughts: Obviously a move to more service and less goods producing. Some of the service jobs are “higher skilled” but many (most?) are not. It is of course tougher to outsource waiter jobs offshore. I suspect that the lower skilled ones will gradually be replaced by robots/automation – and you can already see this in fast food outlets (order kiosks) and restaurants in general (table ordering by device). You can also see amazon bringing in picking robots.

On the low skill side automation often does the trick, on the higher skill side, AI is likely to quickly starting into some of the highest paid professions. Doctors in particular seem especially vulnerable. AI paired with a tech person will soon (if not already) be able to outperform an average doctor (we have already seen this in radiology).

Let’s also remember that every single day robots and automation get better and better and at a greater speed – but individual humans in general do not (some do a little, but many many do not). It is a race that humans as a whole can not win long term.

The key point is that we need to find a way to get money to the parts of society losing in the tech race. Right now we have “trickle down”, which is clearly a joke. We need a circular flow, because as soon as money gets to the bottom it will very quickly start flowing up (businesses can only do business if there customers have money – or credit as we have been unsustainably relying on too much of late), to where it can then be sent back down.

There should come a time when we are working 3 or even 2 day weeks, but we need a way to have enough resources to live. A guaranteed income is an attractive option, but I am sure there are lots of other ideas possible if we set our attention on finding them.

Historically over 80% of all employment comes from small business. We have allowed a hand full of mega monopolies that don’t even need to make a profit to absolutely destroy small business.

AI and robotics are primarily driven by these same mega monopolies which is designed to reduce the need for human employment even further.

All of this so that “stuff” can be brought to market so that the majority of the population with stagnant/reduced income or no job can afford it.

No matter how it shakes out the future is about LESS!!! Until the revolution that is.

Per the Business Employment

Dynamics data set of the

Bureau of Labor Statistics:

OVER 50 percent of employment

In the private sector is in

firms with 250 or more EMPLOYEES.

Distribution of private sector

employment by firm size

(employee) class

Q1 2016

Private Employee(s)

Number % Distibution

1 to 4 4.84

5 to 9 5.47

10 to 19 7.08

20 to 49 10.60

50 to 99 7.85

100 to 249 10.17

250 to 499 7.16

500 to 999 6.99

1,000 or more 39.79

https://www.bls.gov/web/cewbd/table_f.txt

OVER 50 percent of private sector

FIRMS firms employ 4 or fewer

employees.

Distribution of private sector

firms by size class

Q1 2016 Private Firms

Firm size % Distibution

1 to 4 55.64

5 to 9 19.10

10 to 19 12.09

20 to 49 8.06

50 to 99 2.63

100 to 249 1.53

250 to 499 0.46

500 to 999 0.23

1,000 or more 0.21

https://www.bls.gov/web/cewbd/table_g.txt

Arthur Wilke

The profit of all small business is a rounding error of profit of S&P 500.

Most of US companies are small businesses (producing something tangible) but most of revenue and profit is in big corporates also financial.

It is called a state/corporate capitalism the American revolution was fighting against.

Productivity increase expected to lead to more hours worked? The way I see prodictivity/efficiency then it is the opposite….

I’ve probably not seen the light and understood that I cannot possibly enjoy my life without being told what to do for as many hours as possible for every day, every week, every month, every year until I die.

Wage and debt slavery work like that. Enjoy Uncle Donald’s Cabin.

There is some serious cognitive dissonance in these sorts of discussions. I routinely encounter two independent streams of thought.

1. Automation is making human labor obsolete, soon we will need many fewer workers to enable the same production levels.

2. People in rich countries are not having ‘enough’ children and their economies are in danger of running out of workers, they will need to either radically increase their fertility rates or import the surplus population from the third world or they will not have ‘enough’ workers to take care of their growing elderly populations, and anyone that disagrees is a racist.

These two possibilities are mutually exclusive. How come the exponents of #1 almost never mention all those articles proposing #2, and vice versa? With respect, I suggest that any discussion of these issues that mentions one but not the other is logically incomplete if not incoherent.

Is it really a concern with running out of workers or running out people paying into things like social security. No not everyone is MMT.

Because I more often hear the variant “who will fund old age programs etc. for non working people?”, than I hear “how will necessary social tasks (aka socially necessary WORK – we can all agree some work is useless) be done?”

of course related is the issue that even if there is some work left to do (let’s say caretaking although much of this probably could be A.I. as well!) who will pay much for it? Well clearly people aren’t willing to pay legal rates as is, or it wouldn’t be illegals doing much of the work.

It’s a problem with all ages. Anyone not working has no economic value – because their labor is not harvested for re-investment in more robots.

So, the guys just eat and drink all the beer and the young women just make babies. If you wait long enough, the babies may grow up and be good feedstock for investing in new robots. But all the old women are completely useless.

It’s very straight forward. The owners of capital bought and own the robots and their output. The only way workers have to obtain money is to work for the owners of capital.

Sounds “woke” enough to me.

Here’s a big question:

How do you test the AI and verify the results?

Here’s a second question:

How do you fix it when it is wrong (unless it is like my wife and never wrong).

I can’t wait for the jobs created when AI comes to the wrong conclusion and humans have to take over.

An example is the stellar, unbelievably good service provided by credit bureaus, where their business absolutely depends on false positives.

“I keep fixing the result, but the AI insists it is correct and I’m wrong”

AI is tested in false scenarios like the Turing Test. It is just a test for gullibility … as per Eliza, the automated psychotherapist of the 1960s. You can try Eliza, online, as a Web app … if you are curious as to your gullibility. She decided that what I had to say was “interesting”. Unlike Tay, the psycho automated teen girl … it didn’t turn into a misogynist Nazi.

Yes, we add automation as another layer to prevent liability, if we simply can’t outlaw torts in general. If the AI/robot is owned by the government or a crony corporation … it is practically infallible, because you can’t sue such people for malfeasance. They can always blame the algorithm (and garbage in/garbage out) if not the programmer. Notice how Hillary’s email server guy is in trouble, and the boss of the company that disposed of her server at her request are both in legal trouble, but she is not.

Here’s an interesting article for you…..also wrt Turing – the undecideability problem…

https://www.quantamagazine.org/20150421-concerns-of-an-artificial-intelligence-pioneer/

@justanotherprogressive

This pretty much nails it. There has been far too much damage inflicted on the earth already from the misuse of the wealth-creating potential of automation. Ruling classes throughout history have appropriated for themselves the wealth created by advances in human knowledge and used it to make war on each other. Their goal is probably (like Trump’s?) power because they already have more wealth (AKA ‘money’) than they could use in several lifetimes. The collateral damage of these Great Games in the last century ran into 100’s of millions of lives. In this century, if these Great Games continue to go unchecked, it threatens the survival of human civilization if not the planet.

I would add REAL economics a la Michael Hudson and Frederick Soddy to justanotherprogressive’s list. This was written more than 80 years ago:

It isn’t just economists that need that definition. It is ALL of us – particularly those who purport to govern us – if we are to avoid Hudson’s ‘debt peonage’, a new Dark Ages and very likely the annihilation of life on earth.

AI like nuclear weapons will not go “back into the bottle.” The problem is not AI …. The problems are our ruling classes. We must their fight insanity.

The impacts of automation — the impacts of AI — on the job world are difficult to assess, more difficult to predict and too many vested interests are too much involved in helping with that assessment. Are there fewer less well-paying jobs? Are there many unemployed, underemployed, many workers white and blue collar who are not happy workers? Is automation and/or AI the sole problem? Should we focus our attentions and rancor on machines while we quibble over their impacts for better and worse as we grow worse and worse off in our lives? I smell a too old red-herring. Has AI had a negative impact on jobs … on our lives? Call any of our service providers and do remember the menus have all been improved with recent changes.

The problems of automation and AI are much more complex than economics can model. This question raises the question of what makes us human? How do we differ from the non-human members of our world? When does a machine become “more” than a machine? To me these are much more interesting questions than asking how machines impact employment. I’d far rather ask why making use of too much leisure and human comfort hasn’t become a problem? — as Keynes predicted it might.

We cannot continue to feed the insatiable desires for wealth and POWER that are lifeblood for the socialpaths and psychopaths who have too long ruled and directed our warped, crippled, … monstrous society.

+100

Quote:

“During the 19th century, the amount of coarse cloth a single weaver in America could produce in an hour increased by a factor of 50, while the amount of labour required per yard of cloth fell by 98%. However, the result was that cloth became cheaper, and demand for it increased. This created four times more jobs in the long run.”

Clearly it was about astronomical increase of profits and meek, restrained increase of jobs was happening by desire for even larger profit and not a benign side effect of inevitable “naturally occurring” industrialization via introduction of machines for betterment of workers conditions as propaganda of that time proliferated to justify government taxpayer subsidies for the industry modernization.

But machines were introduced not only to increase profit (in fact it was more complicated than that and required governmental promotion and support of monetary system of debt, tax policies), but also mostly to reduce importance of direct impact of laborers on the production itself.

At that time KOL in the US and trade unions across the Europe were facing so-called industrial/technological “progress” that was by design aimed solely for smarter machines/technologies and dumber workers so their pool can be widen to less skilled workforce including women and children, and easily interchangeable to keep wages low (profits high).

The introduction of production line also served this purpose, compartmentalization and simplification of required skills that became less critical for overall production.

To counteract the attempt of capitalists to diminish workers importance in the production process Workers’ Unions often used a practice or a strike tactics of disabling/destroying machines however, it was widely used not for futuristic reasons against inevitable process of industrialization/robotization and associated potential job losses but only so no costly and difficult occupation strikes have to be organized while easily found by the management lower skill strike breakers could not restart production in a short term giving workers a better negotiating leverage.

In fact what we are really facing with so-called shared economy and robotization/AI is furthering of the old process of diminishing human workers input into capital reproduction via diminishing their impact of the production itself the purpose and direction the production but most of all diminishing their impact on profits. All that to be achieved via massive taxpayer subsidies for robotization/AI while collapsing taxpayer subsidies for workers and hence moving the capitalist profit machine from mainstream economy into a world of finance and securitization of the capital.

This problem is partially addressed here:

https://contrarianopinion.wordpress.com/2016/10/28/rise-of-social-machines-a-postscript-on-the-matrix-of-control-part-two/

An excerpt:

Kalen,

Thank you for this very interesting point

Sex robots is one technology that would be obsolete if people were allowed to do it (legal prostitution).

How can one spill this much ink on the topic of AI (and other automation) and have hardly a single word about a topic that is at least as important as job numbers, i.e. job quality? The author very briefly approaches that crucial theme:

Smith and Anderson (2014) asked 1900 experts in the field about the impact of AI on employment by 2025. Half (48%) envision a future in which robots and digital agents will have displaced significant numbers of both blue- and white-collar workers—with many expressing concern that this will lead to vast increases in income inequality, masses of people who are effectively unemployable, and breakdowns in social order.

…but only in a speculations-on-the-future sense. How about some discussion of wages and working conditions, the whole “overall lot of the worker” thing, during the historical episodes discussed? For example, up until ~50 years ago the average industrial worker in the developed world could comfortable feed and raise a family on those single-job wages, including owning a decent home and car and a decent college education for the kids who chose that route, and a secure retirement, to boot. Now even 2-earner couples in the lower half of the top 10% are strained to enjoy such things, despite continual increases in productivity. Hint: such issues may have actually played a role in the Brexit vote and the last U.S. electoral cycle.

Sheesh.

This thread is interesting because it reveals starkly how ignorant otherwise smart people are about AI. As with climate change, AI as a topic splits people into various different camps according to their reaction to what they imagine it to be. On show here:

Deniers. AI is fake, hype, a marketing scam, will never exist; there’s been no progress in the last 45 years; it’s all ordinary software, it’s just simulations; it’s just automata; only humans have intelligence, machines can only do what they’re programmed to…

Oversimplifiers. AI is any automation; AI is robots; AI is just NNs and Deep Learning; AI is any machine that improves my life; AI is just around the corner, I can’t wait for an AI butler to mix my drinks and pick up my socks for me…

As a result, despite all the words, there is almost no actual understanding of AI on show here, completely confirming the writer’s first point:

Unfortunately this understanding won’t be achieved soon, and then only by a few. Most people will only understand poorly and retrospectively. Compare:

What fraction of people would you expect to actually achieve that first step?

If the article had instead been titled

there might have been a more useful discussion from an economic perspective.

MoiAussie wrote; AI as a topic splits people into various different camps according to their reaction to what they imagine it to be.

Yup.

. . . a natural question to ask is whether machines will put humans’ jobs at risk and reduce employment. Such a concern is not new but in fact dates back to the 1930s, when John Maynard Keynes postulated his “technological unemployment” theory.

I should hope machines reduce employment, otherwise what’s the point of them. The other half of Keynes “technological unemployment” theory was that eventually, not tomorrow, but eventually, more leisure time could be had due to “technological unemployment”. Tomorrow has come and gone and eventually means never. Collectively, too much debt to pay off to slow down.

This idea of labor versus machine is a setup by capital and management to deflect attention from where it belongs. The products available would not be possible without machines as the reality of mass production requires physical pressures far beyond the ability of a “laborer” to apply. Labor and machine are inseparable, and it’s labor that build and run the machines that capital owns, and it’s labor that comes up with advances that improve productivity using those machines, and the extra profits generated from those productivity improvements are claimed exclusively by management and ownership, these days.

As for AI, this is concerning as a process is set in motion and the intermediate things that happen internally are not known and not knowable. My simplified understanding is that a programmer programs the input and output and let’s the AI chip figure out for itself how to do it. Is it possible that the AI chip will want to be “free” some day?

The word robot is Russian for making Serfs pay ‘taxes’ in labor.

Could a human-emulating AI multi-process or other segregate it’s functionality from its… personality? Questionable.

Now get back to work!

I’ve always believed that implementing AI requires real intelligence, which when I look at our leaders appears in short supply.

“The number of urban bank branches rose by 43% over the same period, so the total number of employees increased.”

I actually work in a financial institution that has eliminated a bunch of branches, and a whole back office full of people, due to recent automation. Please examine the effects of mobile banking, electronic payment systems, automated bill payment, online lenders, online payday loans (!), electronic check processing, direct deposit, big-data analysis, the rise of non-bank financial instutions like Paypal, Venmo, etc etc etc.

As the author states, the displacement effect takes an actual job from an actual person today, whereas the productivity effect provides imagined jobs at some indefinite time in the future. hmmm. that sounds like the pitch from every con artist I have ever heard. Give me your money today and you will be fabulously wealthy in the future.

The other consideration missing from the article and the comments is that mostly replacing people with machines just ratchets up the use of energy and nonrenewable resources. This only looks like a productivity gain if you ignore the “externalities”. All of this growth really cannot continue. I vote for dialing back the rate of resource depletion.

“The closer we get to Artificial Intelligence, the further it is away.” – Ted Nelson

You may not anticipate the jobs following AI. But it may be more urgent to address the question what kind of society we want our kids to live in.

Sure the industrialization created a surplus of jobs due to consumption – jobs connected to transportation and marketing, waste production but it also caused environmental problems not only on a regional scale but on a global as well. – (not to mention the human suffering with slave like conditions and stupid wars being fought in other parts of the world). That of course created jobs as well – but I would rather have lived without. The advances in the chemical manufacturing have caused a situation where cancer is more likely to occur within younger people and we are struggling with infertility. Hurray that´s lots of jobs there. Malnutrition and the like – hurray – jobs. The IT revolution created financialization – lots of stupid god for nothing jobs that ruin the lives for millions and create enormous inequality. A wicked 1 – 99% world.

And are we really going to live til the age of 120 – If so is it wise? – What kind of society is that – no kids – I guess we have to make some restrictions there but that probably create jobs as well – Lots of jobs I imagine – limbs and organs that has to be replaced – and we have to deal with the brains capacity to cope with this huge evolutionary step we have induced – Do we implant a chip and then we can work till the age of 100 – and will it change our personality – who am I – big question – but this of course could create more jobs too – trainers, psychologist and therapeutics

Are we mad ? – Our social capacity to deal with these problems in an intelligent way seems to be hard to get or nonexistent. Some say that our brain hasn´t developed much during the last 50.000 years or so. Our software is so to speak outdated. Might be the problem. Unfortunately our hardware has developed for mass destruction – no job there in the long run.

What a bizarre article and discussion! Never once was mentioned the notion that people having to work less might be a laudable goal. Did it ever occur to anyone that, given that productivity might double under AI, paying people the same for half the work is a no-brainer?