Yves here. On the one hand, it is completely logical for Italy to threaten to leave the Eurozone, since its economy has fared particularly poorly. That in turn is the big driver of its slow-moving-but-getting-steam bank crisis. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has been pointing out for years that with Italy having a primary surplus, it was the only Eurozone country with the economic heft and the fiscal stance for leaving the Eurozone to be a clearly attractive choice.

And that’s before you get to the fact that the Eurozone has created the worst of all possible worlds with the so-called Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive which went into effect in January 2016. It fails to provide for one of the key requirements of a sound banking regime, which is backstopping deposits (that is left to nation-states, many of which have deposit guarantee schemes which are not adequately funded. A deposit backstop should be provided by the regulatory authority, particularly since it is the Eurozone, and not Eurozone members, that controls currency issuance). While the US doesn’t have a credible regime for resolving too big to fail banks either, unlike the BBRD, it didn’t spend years creating a post-crisis set of regulations that actually increases the odds of bank runs.

Italy has been getting the run around in dealing with its ailing banks and on the budgetary front. This might be barely tolerable due to the realpolitik that German officials would be risking their political futures to be seen as being nice to Italy prior to the elections this fall. But there seems to be no realistic plan in the wings for addressing Italy’s banking mess. While the Europeans have made an art form of kicking the can down the road, they don’t seem to recognize that they are in a cul de sac.

Key sections from an instructive post last October by economist Thomas Fazi:

Italy’s latest budget bill – approved just a few days ago – confirms what many government critics have been saying all along: Matteo Renzi’s anti-austerity rhetoric is nothing more than that. Ever since his appointment as prime minister, in February 2014, Renzi has been an outspoken critic of austerity….

The post-earthquake solidarity was short-lived, though. A few weeks later, at the EU crisis summit in Bratislava, Renzi deserted the final press conference with his German and French counterparts because of disagreements over the economy and immigration. In the days leading up to the publication of the budget bill it became apparent that Renzi’s pleas for greater flexibility had fallen on deaf ears. First came Jens Weidmann, the infamous Bundesbank president, who accused Italy of ‘abusing’ the flexibility clause contained in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and urged Renzi to focus on structural reforms and debt reduction. Then it was the turn of Pierre Moscovici, the European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, who stated that the SGP ‘works fine’ and ruled out granting further flexibility to Italy (even though he had just given Spain and Portugal reprieve from EU budget rules for running much higher deficits than Italy – twice as much in Spain’s case). Finally, Mario Draghi cut the dispute short by declaring that EU rules already provide for ‘a lot of flexibility’ and that ‘countries… should think more about the composition rather than the size of their budgets’ (despite his numerous calls in recent months for greater fiscal support to the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) policies)…

In view of the two sides’ official positions – on one hand a prime minister who has repeatedly denounced the eurozone’s fiscal rules, and is in charge of a country facing the longest and deepest recession in its history, on the other a European establishment that insists on further austerity – an uninformed observer could be forgiven for expecting Renzi to defy EU rules and unilaterally hike the deficit. Everyone else in Europe appears to be breaching the rules: not only are Spain, Portugal, France and Greece well above the SGP’s 3 per cent deficit-to-GDP limit, but Germany has been aggressively violating the EU’s trade surplus rules for years.

But our imaginary observer would have been disappointed: not only does the recent budget bill not foresee an increase of Italy’s fiscal deficit in 2017; it actually foresees a reduction from 2.6 per cent now to 2.4 per cent. And not because the economy is expected to magically start growing – the estimated GDP growth rate for 2017 is a meagre (and overoptimistic) 1 per cent – but because the government has shamefully accepted to implement further austerity measures, in the form of additional budget cuts (even though Italy has reduced government expenditure more than any other member state since the start of the crisis).

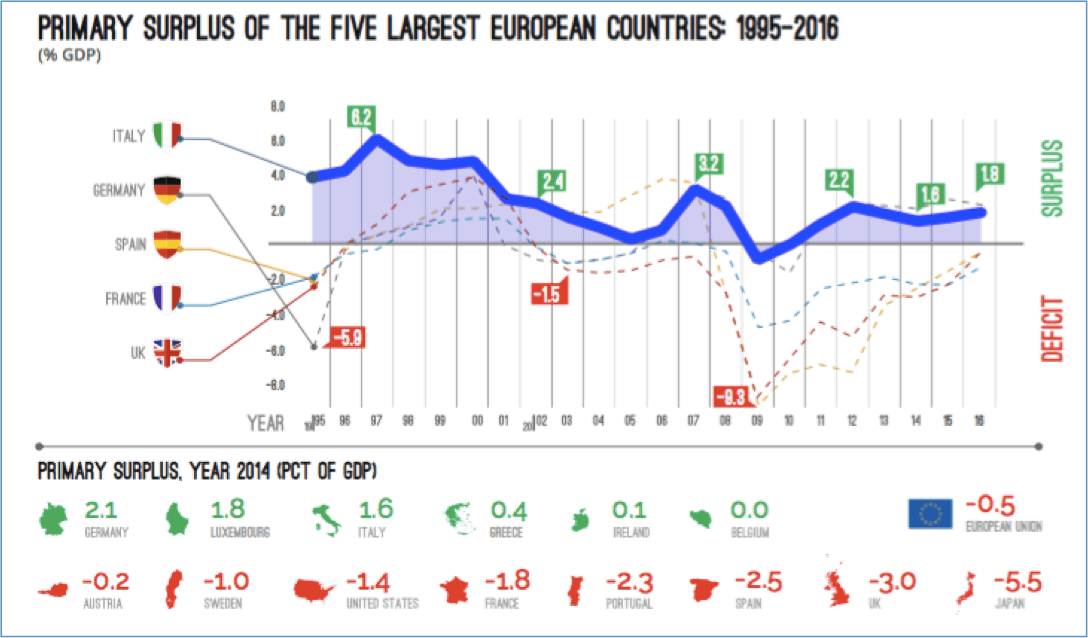

To understand the disastrous implications of this decision it is important to understand the distinction between the primary budget balance and the overall budget balance. It is a common misconception that when we talk of ‘budget deficits’ we are talking uniquely of government revenues minus expenses: that is, governments spending more than they collect in taxes. However, the overall budget balance includes the interest payments on the existing debt. The primary balance, on the other hand, refers to how much a government earns, minus what it spends, not including interest payments on the existing debt – so logically this is the measure that we should look at when assessing whether a country is pursuing an expansionary or contractionary fiscal stance, and whether we are dealing with a ‘virtuous’ or ‘profligate’ nation, in the parlance of our times.

This is Italy’s case: despite its reputation as a reckless spender, it is one of the few countries in Europe (and in the world) to have run a significant primary surplus – meaning that, on average, it has consistently earned more than it has spent, excluding interest payments – since the early 1990s.

Source: Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance based on AMECO-European Commission data

However, this has never been sufficient to cover the country’s high rate of interest expenditure, averaging around 5 per cent of GDP since 2000 (a legacy of the sky-high interest rates of the 1980s), so the state has had to take on new debt each year simply to service its old debt – hence the overall deficit. The same goes for a number of other countries: according to data from the European Commission, between 1992 and 2008 the eurozone has constantly registered a primary surplus. Even if we look at the ‘profligate’ PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) we see that before 2008, three (Italy, Ireland and Spain) had primary budget surpluses and one (Portugal) had a near-balanced primary budget. Greece was the only country with a serious primary budget deficit.

Yves again. A reader might say, “So why hasn’t Italy left the Eurozone?” The problem, as we like to say in Maine, is you can’t get there from here. It would take a bare minimum of three years, which means more like six or more, to re-introduce the lira. It took eight years of planning and three years of implementation to launch the euro, and that was when there was tons less computer code in the various elements of the payment system than now. Italy is not in control of its destiny, since it will take the cooperation of many players, such as international banks, to make the all the needed changes. Even in a negotiated exit with assistance of all the needed parties, this is a complex, time-consuming, and difficult undertaking. If Italy were to attempt to crash out, you’d see results like those in Greece when the ECB cut off its banking system: a near complete shutdown of imports (which in Greece’s case included essentials like food, fuel, and pharmaceuticals), with Greece on the verge of having food shortages after two weeks.

So while we have the seeming insurmountable force meeting an immovable object, what appears most likely to break is the Italian banking system, which would send shockwaves to the rest of Europe.

By Don Quijones, Spain & Mexico, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

Nerves are fraying in the corridors of power of the Eurozone’s third largest economy, Italy. It’s in the grip of a full-blown banking meltdown that has the potential to rip asunder the tenuous threads keeping the European project together.

In his annual speech to the financial market, Giuseppe Vegas, the president of stock-market regulator CONSOB — a consummate insider — delivered a bleak prognosis. The ECB’s quantitative easing program has “reduced the pressure on countries, such as ours, which more than others needed to recover ground on competitiveness, stability and convergence.”

But it hasn’t worked, he said. Despite trillions of euros worth of QE, Italy has continued to suffer a 30% loss in competitiveness compared to Germany during the last two decades. And now Italy must begin to prepare itself for the biggest nightmare of all: the gradual tightening of the ECB’s monetary policy.

“Inflation is gradually returning to the area of the 2% target, while in the United States a monetary tightening is taking place,” Vegas said. The German government is exerting mounting pressure on the ECB to begin tapering QE before elections in September.

So, too, is the Netherlands whose parliament today treated ECB President Mario Draghi to a rare grilling. The MPs ended the session by presenting Draghi with a departing gift of a solar-powered tulip, to remind him of the country’s infamous mid-17th century asset price bubble and financial crisis.

For the moment Draghi and his ECB cohorts refuse to yield, but with the ECB’s balance sheet just hitting 38.7% of Eurozone GDP, 15 percentage points higher than the Fed’s, they may ultimately have little choice in the matter. As Vegas points out, for Italy (and countries like it), that will mean having to face a whole new situation, “in which it will no longer be possible to count on the external support of monetary leverage.”

This is likely to be a major problem for a country that has grown so dependent on that external support. According to the Bank for International Settlements, in 2016, international banks in particular those in Germany reduced their exposure to Italy by 15%, or over $100 billion, half of it in the last quarter of the year. ECB intervention helped plug the shortfall, at least for a while. But the ECB has already reduced its monthly purchases of European sovereign debt instruments, from €80 billion to just over €60 billion.

As the appetite for Italian government debt falls, the yields on Italian bonds will rise. The only market participants seemingly still willing and able (for now) to increase their purchase of Italian debt are Italian banks.

Over a two-month period, Italian banks increased their holdings of Eurozone government debt by €20 billion, with €12.3 billion of newly conjured funds poured into Italian debt alone, according to a joint study by the ECB and Jefferies International. It’s the highest increase since 2015, bringing Italian banks’ total holdings of Italian government debt to an eye-watering €235 billion. When rates begin rising on that debt, those same banks, many of which are already verging on insolvency, will begin bleeding new losses.

This is a ticking financial time bomb. As the FT recently reported, just about every solution hurled at Italy’s financial crisis has come to naught. That seemingly includes the latest plan-B which essentially involved securitizing billions of euros of toxic debt and spreading it as far and wide as possible, with the assistance of Wall Street banks. According to the FT, that plan has already “floundered.”

In the meantime, Brussels continues to dither over how to proceed with the bailout/bail-in of Italy’s most bankrupt big bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, which just announced new quarterly losses of €169 million. Other major banks, most notably Banco Popolare di Vicenza (BPVI) and Veneto Banca, are in similar dire straits. Once again, Italy’s regulators are urging caution over applying the EU’s bail-in rules to the exact letter of the law.

In his address, Vegas proposed introducing a safeguard threshold of €100,000 euros for the banks’ bondholders, many of whom are ordinary Italian citizens, with combined holdings worth some €200 billion, who were told by the banks that their bonds were a secure investment. Not any more.

“The management of crises may require timely intervention that is not compatible with the mechanisms in Frankfurt and Brussels,” Vegas added.

To get his point across, he issued a barely veiled threat in Frankfurt and Brussels’ direction — that of Italy’s exit from the Eurozone, a prospect that should not be altogether discounted given the recent growth of anti-euro sentiment and rising political instability in Italy. So he threatened: “Merely the announcement of a return to a national currency would provoke an immediate outflow of capital that would seriously jeopardize Italy’s ability to refinance the world’s third biggest public debt.”

That’s the ultimate threat: monetary sovereignty — its own currency — under very messy conditions. Let others pick up the pieces of the Eurozone.

Italy’s latest plan is just splendid: Selling securities backed by defaulted loans to NIRP refugees. Read… Here’s Italy’s Latest Plan B Where Desperation Meets Insanity

Everything in both contributions very precise and accurate for the details of the precedings, of the grim situation and of the ticking time bomb, except for the final fact that here in the boot country the idea of threatening an euroexit appears to be missing . Incidentally, after the fall of Berlusconi and the 2011/2012 crisis,there were rumors that a contribution to his fall came from the fact that in some meetings he had carelessly already threatened to get out the euro.Then A.Evans-Pritchard relaunched some quotes from the former ECB executive board member Mr.Bini Smaghi raising some limited interest.

Thank you, Lou.

Bini Smaghi was rewarded with the chairmanship of French bank Societe Generale as the door revolved from the ECB. One wonders if he ever looks at the toxic waste on the bank’s balance sheet and those of SocGen’s French peers. If the Italian system goes down, as opposed to the current slow motion bank run, some observers reckon French banks will collapse before my Teutonic TBTF. Luckily for my employer, we have big investors from the Middle and Far East, so could get bailed out that way.

I’m happy for you that in case of dire straits you’re gonna find a solution with your investors, as for my country, if recent history is teaching something, I’m reasonably confident that we will do “whatever it takes to find us in the possible worst position” :-)

I can see things all coming to a point where the path of least resistance is keeping the euro, but reining in the German-Dutch austerity freaks. The economic situation alone seems headed this way. Taken together with the incipient social instability, it looks like the neoliberal technocrats are eventually going to get kicked to the curb.

The big problem is: How? I’ve been hoping it would happen through some elections, but so far, no.

The situation is concerning way beyond the financial sphere, which conceivably could be left to stew in its own juices (OK, maybe in fantasy). The EU was justified as a way to prevent future wars in Europe; that’s what it got the Peace Prize for. But there really isn’t any “path of least resistance,” so it could all too easily become the CAUSE of a new war in Europe (I keep thinking of Greece’s inordinately large defense budget).

I fantasize a nuclear option. The Italian police seize Draghi, arresting him, refusing to release him until the criminal cabal of Brussels and Germany release their austerity stranglehold on the EU. They ARE looting the rest of the EU for their personal fortunes.

If only some European leader/victim of the aggressors in Brussels and Germany would grow a pair and take direct action…

Since Draghi is himself Italian, the Germans, etc., would probably just let him stew and name someone else.

This is one of the scenarios that could lead to war. Admittedly, it’s unlikely, but I think the danger is real. Nobody MEANT to start WWI.

Vegas? What a fantastic name for a casino regulator!

Would the ECB really dare to treat Italy the same way it treated Greece?

Italian banks – unlike Greek banks – are systemically important as counterparts to German and French banks. If the ECB were to cut off liquidity to them in case of massive deposit flight to Germany the banks would simply have to close doors, sending massive schockwaves to the French and German financial sectors and economies.

It’s perhaps more likely in the Italian case that the ECB would feel it was forced to keep extending liquidity to the Italian banks – forever.

I think that’s the point that Mélenchon and his economic adviser Généreux understood well – large countries of the eurozone are in reality immune from the type of brutal pressures that the European Commission and the ECB can apply to smaller states such as Greece. His idea (had he been elected) was to simply ignore the austerity instructions from European headquarters and implement all the necessary measures to put the French economy on the path to growth and full employment. All this without leaving the eurozone.

Large states and banking sectors are too big to fail. The ECB knows that. What this means is that countries with the dimension of France, Italy – maybe even Spain – can, if they really want to, follow very different economic policies from those prescribed by the EC and the ECB.

The end game has to be a controlled demolition, with the Elite in on it, before hand … so that wonderful profits can be made in the puts.

‘Controlled Demolition’

Good Luck!

And the smaller states then fully understand they are 2nd class entities in the EU.

One rule for the majors, a second rule for the rest.

It appears to me the EU is hoist by its own petard.

I really don’t believe that the problems are caused by German and Dutch intransigence. They are such accommodating and flexible people.

So the issue is if they really want to, from this point of view my domestic ruling classes , beyond occasionally screaming out loud,appear without hope.Italy is big, but until now it seems she wants to “respect the orders” as for austerity etc.I ask to myself if this is too the reflex of a respect for a European hierarchy of power and egemony about whom a French leftist could care a lot less in every sense.Then, whatever is on the surface,such as corruption etc, the deep problem is that the political ability level of our ruling classes is simply far too low.

According to Yves’ commentary, they already are; even Portugal. It’s quite odd, and reflects on Renzi, that Italy is not.

It would not be by virtue of the ECB action. The results of going to a new currency without having any of the coding done to handle a new currency is what would cause pretty much the same result: an inability to pay for imports.

All deposits at Italian banks would be force-converted to lira. But with no one being able to recognize lira transactions due to lack of coding anywhere (even at the Italian banks themselves!) the only way to pay for imports would be:

1. Euros held by Italian nationals in banks outside Italy.

2. Euros held in cash in Italy.

3. Physical transport of new lira currency (as in cash) across the border, which might or might not be accepted. Presumably one or two particularly enterprising banks would set themselves up fast to take lira to fill this void, but even so, it would be hard.

Note that the Greeks were forced to do 3 with Euros, as in take them across the border or even fly them to London due to the banking system effectively being shut down.

1 and 2 would be depleted pretty quickly.

Also note it would take a bare minimum of six months, and more like a year, to get a currency designed (yes, this is not trivial), printed, and distributed.

Q.: When is the best time to leave the Euro? A.: Ten years ago.

Think of how much better Italy’s position would be if it had started Euroexit after the crisis. Or even back in 2010. They’d be just about done by now. “You can’t get there from here” is only true if you never flippin’ start.

Couldn’t have said it better.

It’s assumed that a major exit would not get cooperation… but Italy owes everybody. Cooperate, help us out, and we will pay back something of what we owe.

Owe the bank a thousand, you’ve got a problem. Owe the bank a billion, the bank has a problem.

An old (but wise) joke.

Question; “Why is D I V O R C E so expensive?”

Answer; “Because it is worth it.”

But their standard of living would me much lower after a full-blown crisis. Italy has a high standard of living and a functioning economy quite larger than that of Russia. Destroying it won’t be the solution.

It sounds like the EU is really the EH. The European Hitman. First the EU banks indulge in all sorts of high-flying debt largesse to the member states because the banks need to “invest” competitively or die; then they and the US banks cause the Crash of 2007 because capitalism has reached its outer limits; then they pretend that it’s no big deal as all the smaller members of the EU (and US states) begin to starve to death like third-world countries; when the EU/ECB can no longer pretend it’s no big deal, the member states are beyond salvaging because the debt burdens demanded by the former totally incompetent banksters has bled them all dry, they buy/ backstop certain sovereign bonds at ZIRP, when it still continues to be a disaster they decide they will have to get real and the strategy will be to save as many of the big banks as possible and never mind the people and the politics. So they raise interest rates, administer the final poison, and say to the states they have bankrupted: It’s your problem. Whereas if the EU were a federation of political states which gave it sovereign taxing authority they could print the money, buy back the debt, eliminate the burden and start over. So who exactly prevents the EU/ECB from this solution? Maybe they all need to go to the PCA and arbitrate some sanity into their lives.

Europe is not a nation and Europeans are not a people. The idea of a United States of Europe is a total fantasy. Europe can only be united as a multicultural empire by the use of massive force as the Ottomans united for awhile most of the Middle East and North Africa. Hitler went a fair way toward this before he fell but there is no current prospect of anything like that happening in the near future.

They covered all the structural problems(2007-2008) of global Fin/Banking system with EASY (credit explosion)in 2009 and kicked the can down, Debt on Debt became the solution until NOW!

Now back to square one!

Printing money doesn’t eliminate the burden, though. That’s the fiction at the heart of our now years-long discussion of the banking crises in places like Greece and Italy. When banks are insolvent, someone has to pay. The political question is who takes the loss. There is no way to avoid losses.

In real terms, banks can default, meaning creditors take the loss. Or states can bail out banks, meaning citizens take the loss. Or states can print a new (old) national currency unit and demand foreign creditors accept that national currency unit at an above market exchange rate, meaning creditors take the loss. Or states can print a new (old) national currency unit and demand domestic citizens accept that national currency unit at an above market exchange rate, meaning citizens take the loss. Or states could tax the rich, meaning the rich take the loss. Or states can counterfeit foreign currencies, meaning holders of that foreign currency take the loss. And so on.

Lots of options for distributing the losses incurred from fraud and mismanagement. No options, however, to avoid paying for those losses.

I must have missed something; didn’t Renzi resign as PM?

Yep. But he just got re-elected as head of the PD (Partito Democratico), beating other candidates who were somewhat less pliable to establishment wishes. Renzi got around 60% of the vote, so the challengers were beaten much worse than Hillary beat (i.e., mugged) Bernie. Unless the 5-Star movement can beat the PD (conceivable, but not real likely), it’s reasonable to assume Renzi and/or his lackeys will be running the show for the foreseeable future.

It might become interesting if push comes to shove – ie Draghi vs Italy, if his role in the miss-selling to those who could face a bail-in is properly examined.

” When rates begin rising on that [government] debt, those same banks, many of which are already verging on insolvency, will begin bleeding new losses.”

Wait a minute, something isn’t clear. What losses? That sounds like the banks’ interest income will rise. Is he talking about capital losses as the value of the bonds declines with the rise in interest rates? Can’t that be solved by holding the bonds, as it can for individuals? It does mean they’re locked in.

Bonds backed by Non-performing loans?!

Good Luck!

No, those are government bonds that the banks are purchasing now.

from WOLF STREET:

‘Under this plan, the bank would slice, dice, and repackage non-performing financial assets, such as loans, residential or commercial mortgages, or other sometimes uncollateralized Italian “sofferenze” (bad debt) into asset-backed instruments which can then be sold to yield-starved gullible investors all over the world. This is riskier than the subprime mortgage-backed securities in the US that played a major role in the global financial crisis.[..]

The FT describes the idea of securitizing NPLs as “subprime derivatives on steroids,” but only in relation to China’s plans to do exactly the same thing with its own non-performing loans, which according to official figures recently surpassed the $200 billion mark. The FT has been a lot less critical of the same plans being hatched in Italy. Some economists are even calling for a Europe-wide securitization of toxic debt..[..]

Wow!

Have they already forgotten why 2008 happened? Are those standing in to buy these ‘toxic’ products that DUMB?

UNBELIEVABLE!

I don’t think that the plan is to buy them with their own money

So many GREY Swans there!

Which one will prick the Bubble and when?

the Italian banks should hire Bernanke or we can air drop him in over Rome the problems will be solved by the end of the week

I am all for abolishing the Euro and going back to national currencies, but as the posts above say, it is just not feasible. And the populists (M5S, Le Pen) know it: all their threats of referendums will come to nothing. Or the moment they come close to power, they will do a SYRYZA and just keep muddling through.

Eventually a solution will have to be found, but it will have to be agreed upon by the southern Euro-countries, the Northerners, the US and possibly all other G20 economies.

I guess that will only happen after a Minsky moment on European debt: Italy has long been borrowing just to pay interest (speculative borrowing), and QE means it has entered Ponzi borrowing territory.

A crash is long overdue. When that happens, we will finally have a more rational monetary system in Europe.

Re “Everyone else in Europe appears to be breaching the rules: not only are Spain, Portugal, France and Greece well above the SGP’s 3 per cent deficit-to-GDP limit,”

Unlike stated above the Portuguese deficit is 2.1% and Portugal is expected to leave excessive deficit procedures in the next two weeks.

The article doesn’t address the pernicious effect of the neoliberal opposition in the affected countries that make counter cyclical policies hard to design politically within the budget strictures imposed by the EU. Once Portugal found a workable left wing political solution that locked out the neoliberals in the left and right the situation improved visibly. Moscovici is partially right as the composition of the budget matters for social peace and justice.

If Germany has exceeded it’s own EU guidelines in terms of trade balance why are all the other EU states not complaining?

Some sins are more sinful than others. Excessive deficits and debt is a sign of poor management skills and moral decay while excessive lending to those with reputed poor management skills is just good banking /snark. Economic success in the eyes of the calvinist EU is a sign of virtue and who would want to punish that ? Likewise, excessive trade imbalances in the pursuit of outsized profits that impoverish your trading partners is no sin or maybe just a little one in the eyes of the EU executive, specially if the those impoverished partners are southerners.

+1

“This is Italy’s case: despite its reputation as a reckless spender, it is one of the few countries in Europe (and in the world) to have run a significant primary surplus – meaning that, on average, it has consistently earned more than it has spent, excluding interest payments – since the early 1990s.” (http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/05/bleak-prognosis-italys-financial-regulator-threatens-eu-return-national-currency.html)

ITALY’S EXIT SOLUTION:

1. Formally announce a ‘Notification To Exit’.

2. Only U.S. Dollars (World Reserve Currency ) will be accepted as payment for exports.

3. Italy will no longer pay interest on its debt effective immediately.

4. Italy will continue to payoff its principle debt now and until it is reduced to zero.

Either this or Italy will only remain if the ECB would issue interest free loans.Period.