Lambert here: Plenty of what looks like technocratic nuts and bolts. Not sure how that “greater fiscal union” thing is going to work out. Greece, along with the rest of the Southern Tier, may have already have as much “union” with Germany policy makers as they would like.

By Marco Annunziata, Chief Economist and Executive Director of Global Market Insight, General Electric Co. Originally published at VoxEU.

The launch of Eurozone QE (ECB 2015) was eagerly awaited by investors and preceded by contentious discussions in Eurozone policy circles. Countries still struggling with weak growth saw it as a necessary step to help a recovery, while Germany and other northern EZ members were worried that ECB purchases of government bonds would ‘mutualise’ government debts and undermine incentives for fiscal prudence. The ECB has done its best to square the circle.

QE Justification and Structure

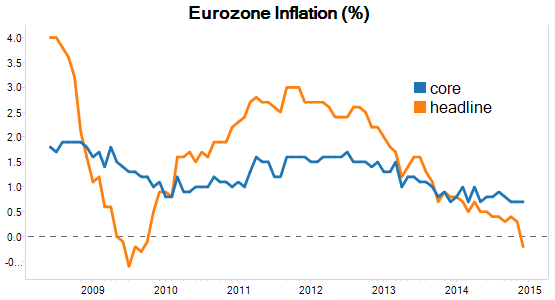

It’s important to note that the ECB’s decision is fully justified by its inflation mandate.

- The ECB was already forecasting inflation below target for the next two years;

- The collapse in oil prices has increased downside risks, and inflation expectations have moved lower.

The QE structure is clear:

- Purchases will be substantial – €60 billion per month (comparable to the Fed’s QE3, Annunziata 2012) until end-September 2016, for a total of over €1.1 trillion.

QE could be extended beyond September 2016 if the inflation target is not yet within reach.

- Asset purchases will now encompass investment-grade bonds issued by governments, national agencies and EU institutions.

This is in addition to asset-backed securities and covered bonds, which were already included in existing programs. Since the latter were running at about €10 billion per month, additional purchases will be in the order of €50 billion per month. This is near the top end of what market were expecting.

- Purchases will be proportional to the shares of EZ national central banks in the ECB’s capital.

These capital shares are proportional to the respective countries’ GDP and population sizes. This aspect was the obvious choice. It reinforces the idea that government bond purchases are undertaken for monetary-policy purposes and not to alleviate the funding needs of specific countries.

Conveniently, this feature will benefit Italy, which has the third largest ECB capital share and the largest public debt burden.

- There will be specific conditions for bonds of countries (like Greece) under EU/ECB/IMF programs.

This, presumably, will require the countries to be in compliance with the program’s conditionality. It may also open the possibility of eligibility even with a sub-investment grade rating. QE could encompass Greek bonds, depending on how things develop after this weekend’s Greek elections.

Risk sharing: Devil in the Details

The devil is in the risk-sharing details (also see Giavazzi and Tabellini 2015).

- 12% of new purchases will consist of EU institutions bonds, and will be subject to risk-sharing.

This is perfectly logical, and these should have very little risk anyway.

- The ECB will hold 8% of additional purchases, and these will also be subject to risk sharing;

- The EZ national central banks will shoulder the risk for the rest of the purchases.

Assuming the 8% held by the ECB does not include EU institutions bonds, this means that 12% + 8% = 20% of new purchases will be subject to risk sharing—as per Draghi’s statement at the press conference.

- Put it a different way, this implies that 91% of government and agency bonds will not be subject to risk sharing.

For every €100 of additional purchases, 88 will be government and agency bonds, which minus the 8 held by the ECB will leave 80 out of 88 as a risk of national central banks.

What the Limited Risk-Sharing Means

The limited risk-sharing sends a message.

- As long as fiscal policy is national, the risk of government debt should stay largely within national borders.

This is an important reminder that additional steps towards fiscal union are needed.

- Without greater centralized control on national public finances, Germany and other northern member countries will always be reluctant to be on the hook for the debt of their more profligate partners.

Sooner or later, this will be a problem. QE, however, suggests this problem is unlikely to arise over the next couple of years.

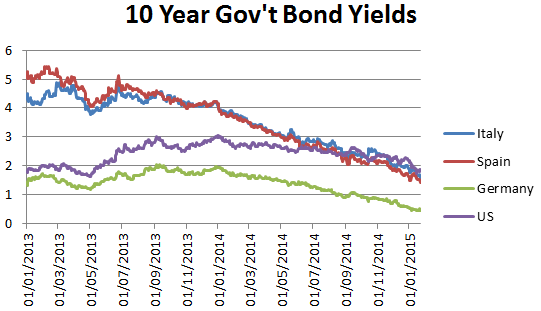

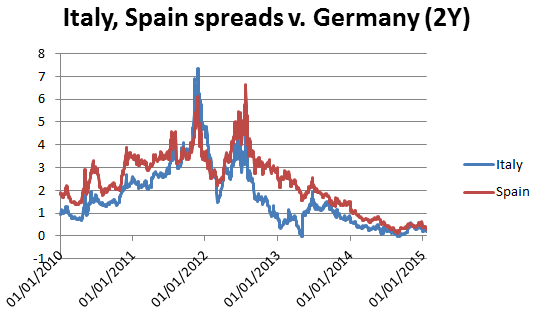

- QE will ease financing conditions and help keep government funding rates at low levels, including for high debt countries.

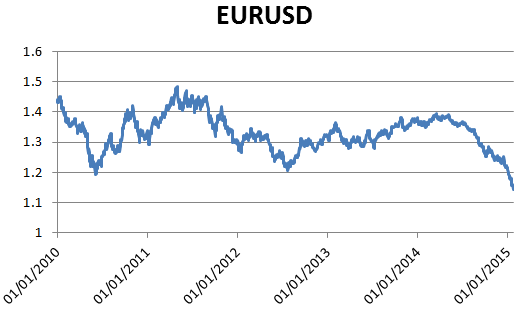

- QE is not enough to restore growth, but it will help.

In 2015, the Eurozone will benefit from lower oil prices and stronger US growth. With QE supporting low interest rates for longer, and an even weaker currency, I see increased potential for upside surprises to Eurozone growth this year.

QE and a better growth outlook, sadly, increases moral hazard risk. Stronger and sustainable growth requires difficult structural reforms to make markets more flexible and create the conditions for more innovation and higher productivity. For governments, however, the temptation to rely on ECB bond buying and a weaker currency will be strong. QE will buy the Eurozone some precious time. But we need progress in structural reforms, improvements in national fiscal policies, and a strengthening of Eurozone institutions for this window of opportunity not to be wasted.

References

Giavazzi, F and G Tabellini (2015), “Effective Eurozone QE: Size matters more than risk-sharing“, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Annunziata, M (2012), “QED: QE3“, VoxEU.org, 17 September.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2015), “Quantitative easing in the Eurozone: It’s possible without fiscal transfers“, VoxEU.org, 15 January.

ECB (2015). “Introductory statement to the press conference”, http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2015/html/is150122.en.html

The disturbing thing is this seems like a very desperate act.

€1.2 Trillion of QE is barely going to budge their interest rates, which are already close to 0.

It’s just enough to keep the super-wealthy from going into deflationary spiral.

Cheaper oil is good ’cause yeah and we want U.S. consumers to pick up our demand slack.

If you squint, inflation can sort of look like growth, maybe we can get people buying houses they can’t afford again and we want U.S. consumers to pick up our demand slack.

Greeks will think they have a right not to starve.

Shift more financial burdens onto workers.

Make it easier to fire workers, confiscate their pensions and reduce their wages.

Europe insists on shooting itself in the knee, but transfusions will keep us from bleeding out. . .

. . .but we need to move on to a bullet in the head. Transfer of all fiscal authority to Germany must proceed with all due haste and the same institutions which have led us to our current crisis must be made more able to crush resistance in future.

If you need a reference for a job as a translator at the European Parliament, let me know.

‘Capital shares are proportional to the respective countries’ GDP and population sizes. This feature will benefit Italy, which has the third largest ECB capital share and the largest public debt burden.’

‘Benefit?’ Probably as beneficial as drinking your own urine. Actually, this aspect illustrates a well-recognized problem with sovereign bond indexes, in both developed and emerging markets. Namely, a market-cap weighted index forces bond managers to load up on the countries that have the most debt outstanding — dogs like Italy and (even worse) Japan.

The largest U.S.-traded international sovereign bond ETF, which tracks the Barclays Global Treasury ex-U.S. Capped index, has a 22.59% weighting in Japan (its top position) and another 11.47% in Italy (its 3rd ranked position). Uggghhh — poison dog doo!

The devil is in the details but outside of member-nations such as Italy and Spain enjoying lower borrowing costs, I’m not sure I see any upside. If 88 percent of the bond purchases still keeps the risks with the issuing member-nation, then I don’t see an increase in bond issues from member-nations with stronger balance sheets. If that’s the case, the ECB will be left wanting in using up its funds in search of bond buying opportunities, and the desired effect, increased money circulation, will not materialize.

Am I missing something, or was this simply more of a PR ploy to encourage a psychological upswing in the outlook for the EU?