Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

In his first State of the Union address in January 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson told Congress that “many Americans live on the outskirts of hope—some because of their poverty, and some because of their color, and all too many because of both.” Johnson declared “unconditional war on poverty in America” and challenged Congress to act on income, jobs, health, education, and housing.

Johnson’s call was propelled by the civil rights movement and its dual struggle for equal political rights and tangible economic justice for all. After all, the name of 1963’s March on Washington was “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” which included in its demands “a massive federal program” for all unemployed workers—black and white—and a minimum wage that “will give all Americans a decent standard of living.”

In 1967-8 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. prophetically urged America, as his friend, the late Vincent Harding, described:

”—in word and deed—to break out of our destructive triple bondage to racism, materialism, and militarism.”

Dr. King organized a Poor People’s Campaign and March on Washington with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1968 which was carried out and led by Ralph Abernathy in the wake of King’s assassination.

We are now fifty years from the enactment of various anti-poverty programs, and at first glance, the numbers are discouraging. The poverty rate fell by almost half from its peak of 26 percent in 1967 to 13 percent in 1980. But since then, there has been little substantive decline, with 13.5 percent of the U.S. population in poverty in 2015.

Some critics claim that although programs may have been well-meaning, they have failed. Others go further, saying poverty is overstated because official measures do not count the cash value of benefits. And some even argue poverty is less pernicious because most poor households have basic necessities of a decent life, like air conditioning, television, or mobile phones.

Like the critics, this report shows that poverty rates are stubborn, and have not declined as much as the 1960s reformers hoped. But unlike the critics, it shows that adding in net benefits does not result in significantly lower poverty rates. And although black Americans suffer the most commonly, poverty cuts across race—in 2015, almost 18 million white Americans, 12.2 million Hispanics, over two million Asians, and 9.6 million black people lived in poverty.

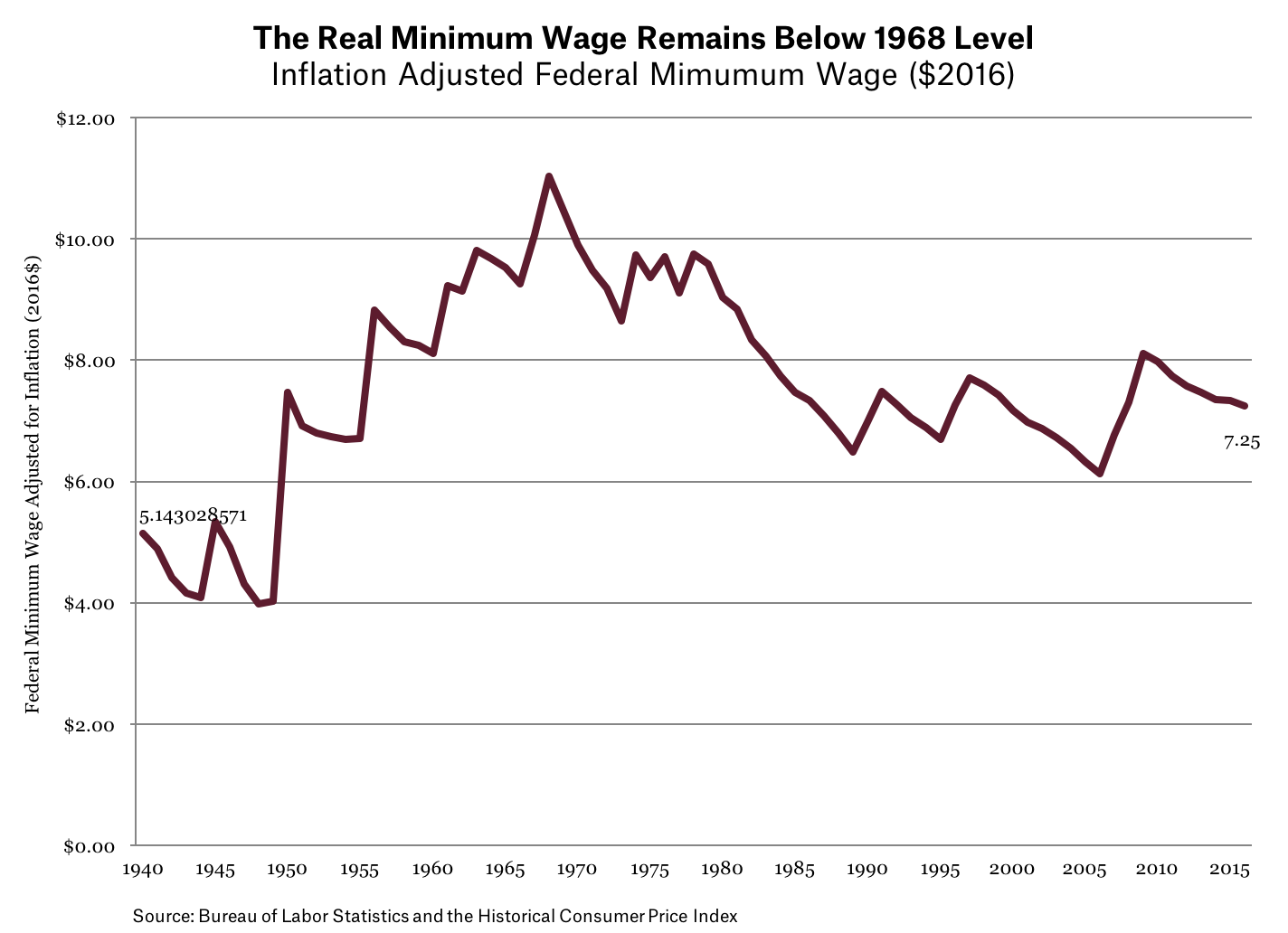

But this report also documents that without government programs, tens of millions of Americans would be in poverty. This is especially important because of economic and income stagnation. Inflation-adjusted wages and income for the vast majority of Americans peaked in 1999, the real value of the minimum wage peaked in 1968, and income inequality has shot to levels not seen since the “Roaring ‘20s,” with the top one percent of Americans capturing over 90 percent of all income gains since the Great Recession ended.

Given these economic problems, it is perhaps surprising that more Americans have not fallen into poverty. This report looks mostly at direct relationships between economic factors and poverty. A deeper analysis of poverty, would analyze inequality and the intertwining of low incomes, stagnant economic growth, subpar education, inadequate housing and health care, and a harsh and discriminatory criminal justice system. For now, it is enough to note not only the gaps that remain to fulfill America’s promise for all, but also the critical role that existing programs play in keeping poverty from being even more extreme.

Key Points

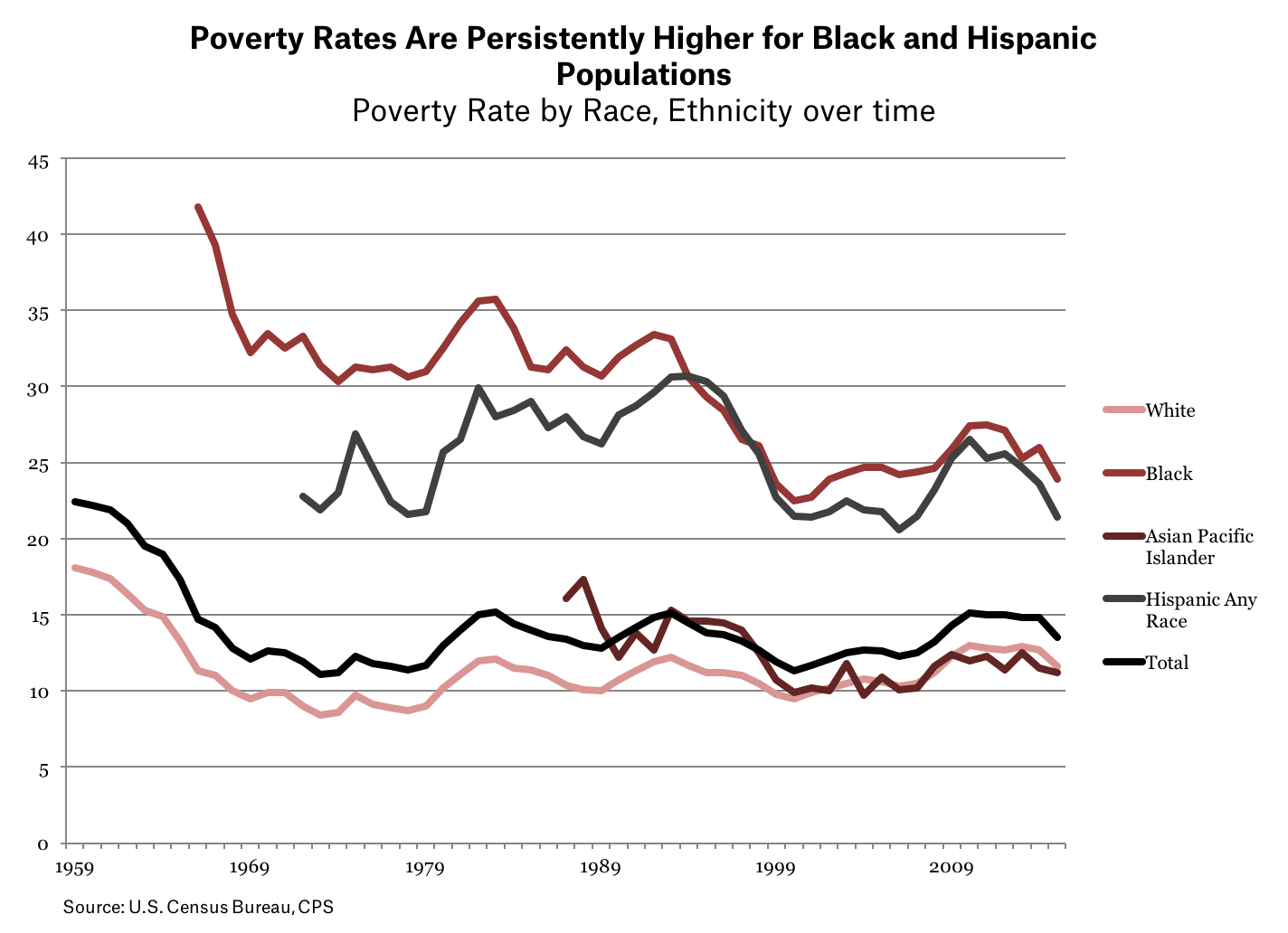

Though poverty is a problem across the U.S., poverty rates are persistently higher for black and Hispanic communities.

- Women and children also face persistently higher rates of poverty.

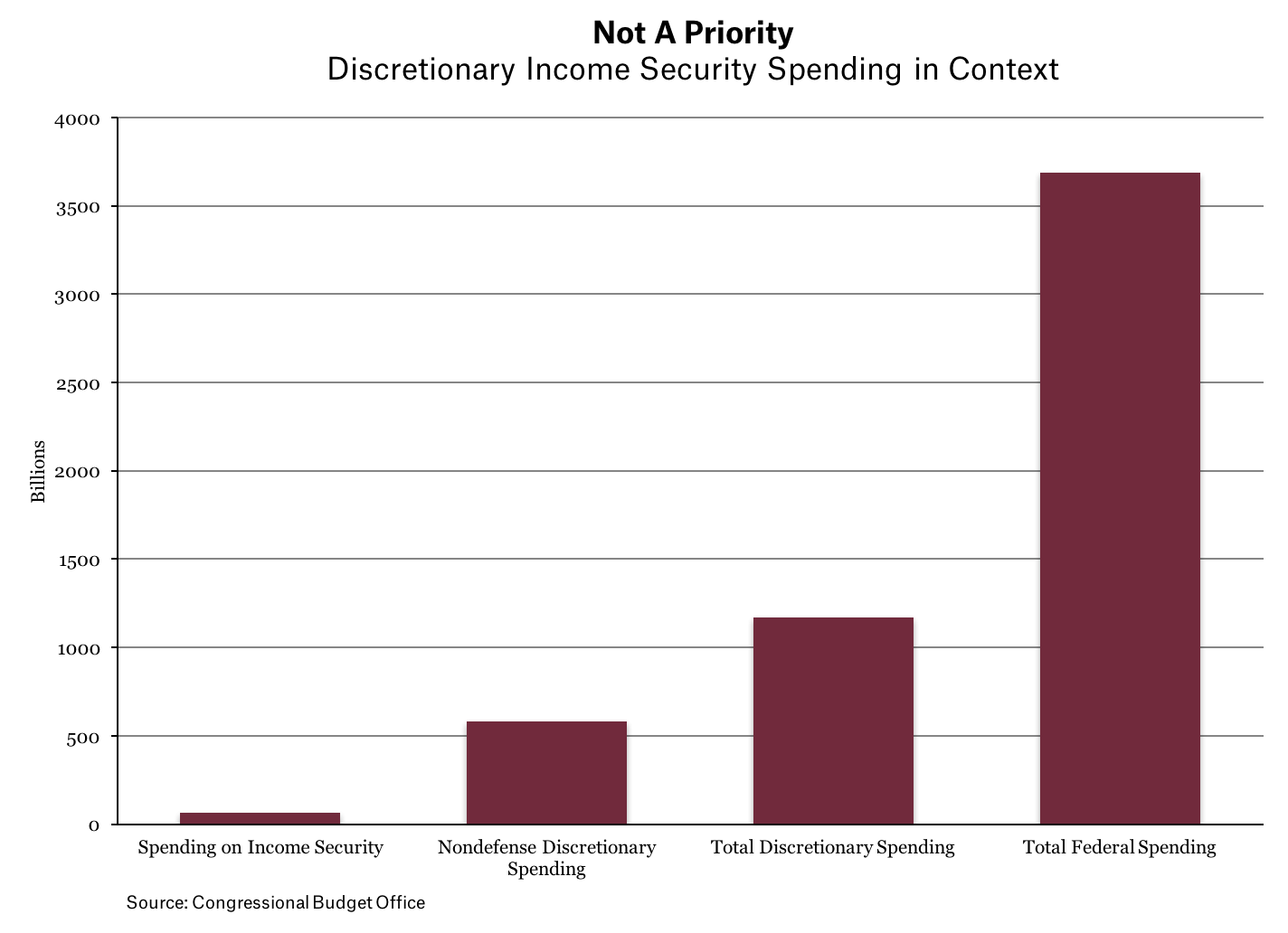

- Income security spending by the government makes up only 0.4 percent of GDP.

- Though a small portion of government spending, economic support programs keep millions of Americans out of poverty.

- Growing inequality in income and wealth contribute to persistent poverty.

Trends in Poverty

During the early years of the War on Poverty, the overall poverty rate dropped sharply, through a combination of economic growth and increasing social spending. But in the mid-1970s, the rate flattened out, and has not moved much since then.

Mirroring economic inequality and discrimination, poverty rates among black and Hispanic communities remain the highest among all racial groups, although early social spending (including Social Security) brought down poverty for all groups. Black poverty in particular dropped sharply in the 1960s and again in the 1990s, while still remaining the highest among racial and ethnic groups.

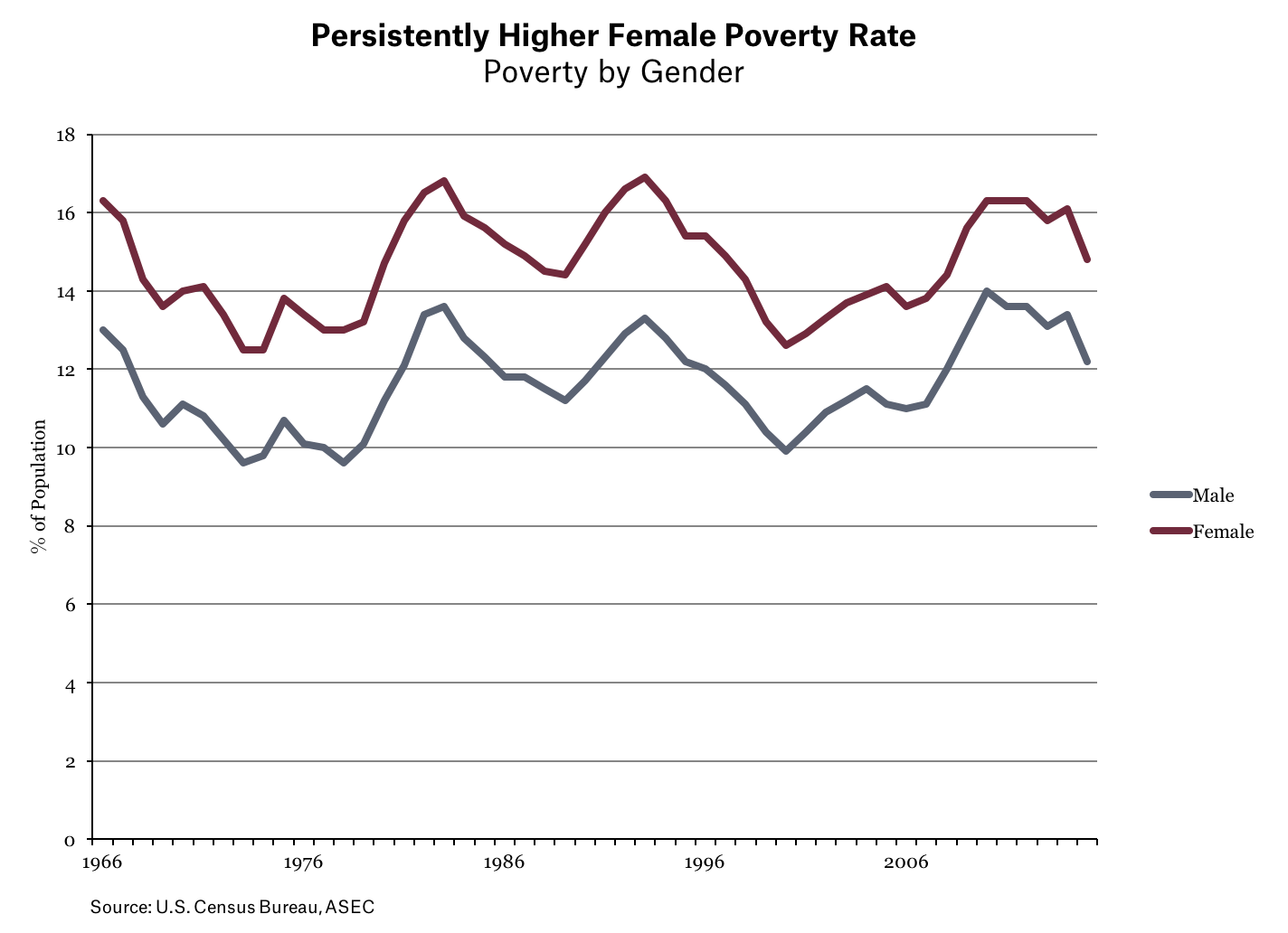

Poverty for women also is higher than for men, mainly because women have worse labor market opportunities in terms of wages, hours, and occupations. In 1966, poverty was 33 percent higher for women than for men; the gap fell to 26 percent in 2015, but it remains large and persistent.

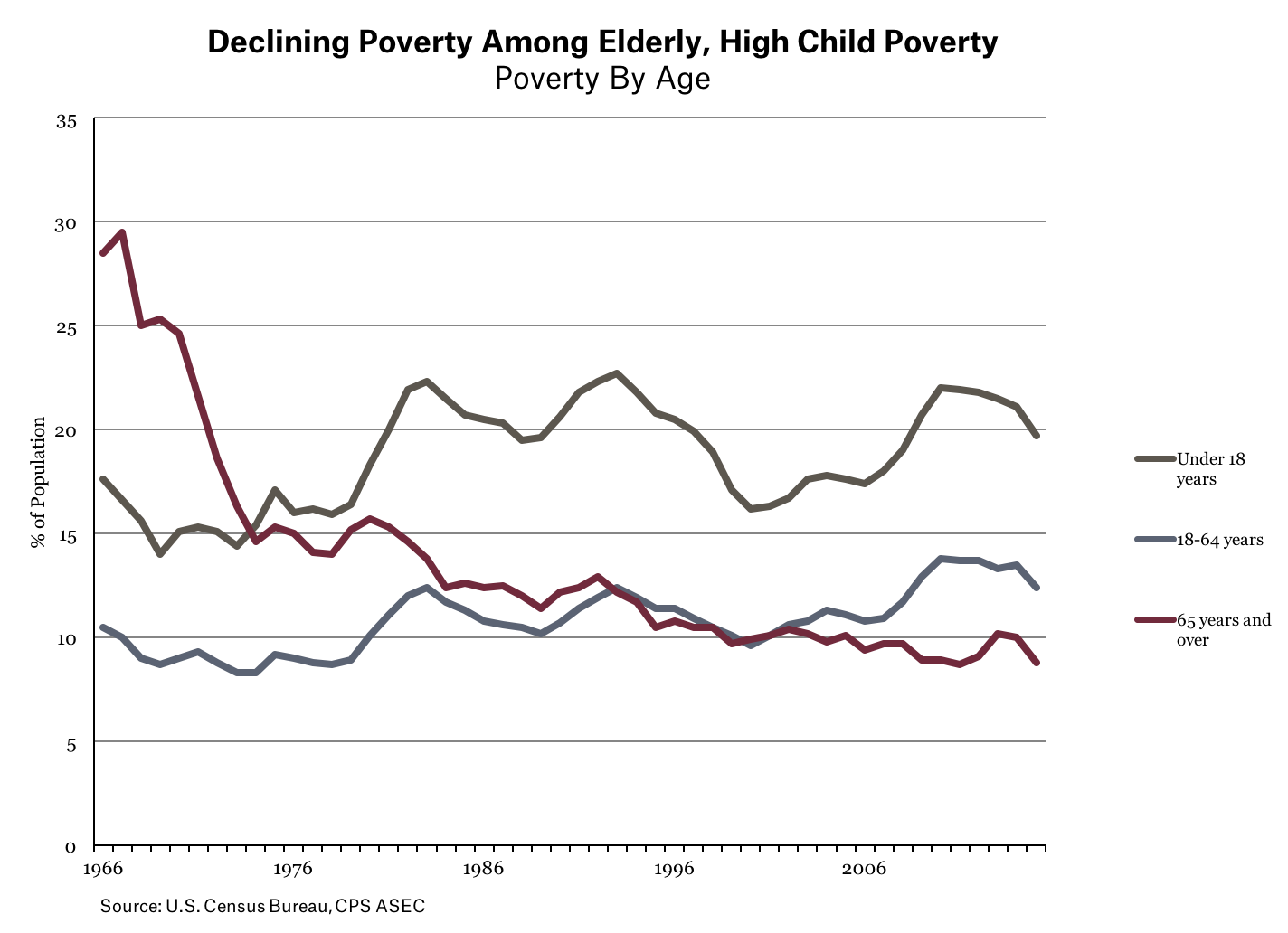

The greatest progress against poverty has come among older Americans over 65, through improvements in Social Security. Meanwhile, child poverty has trended higher since the late 1970s.

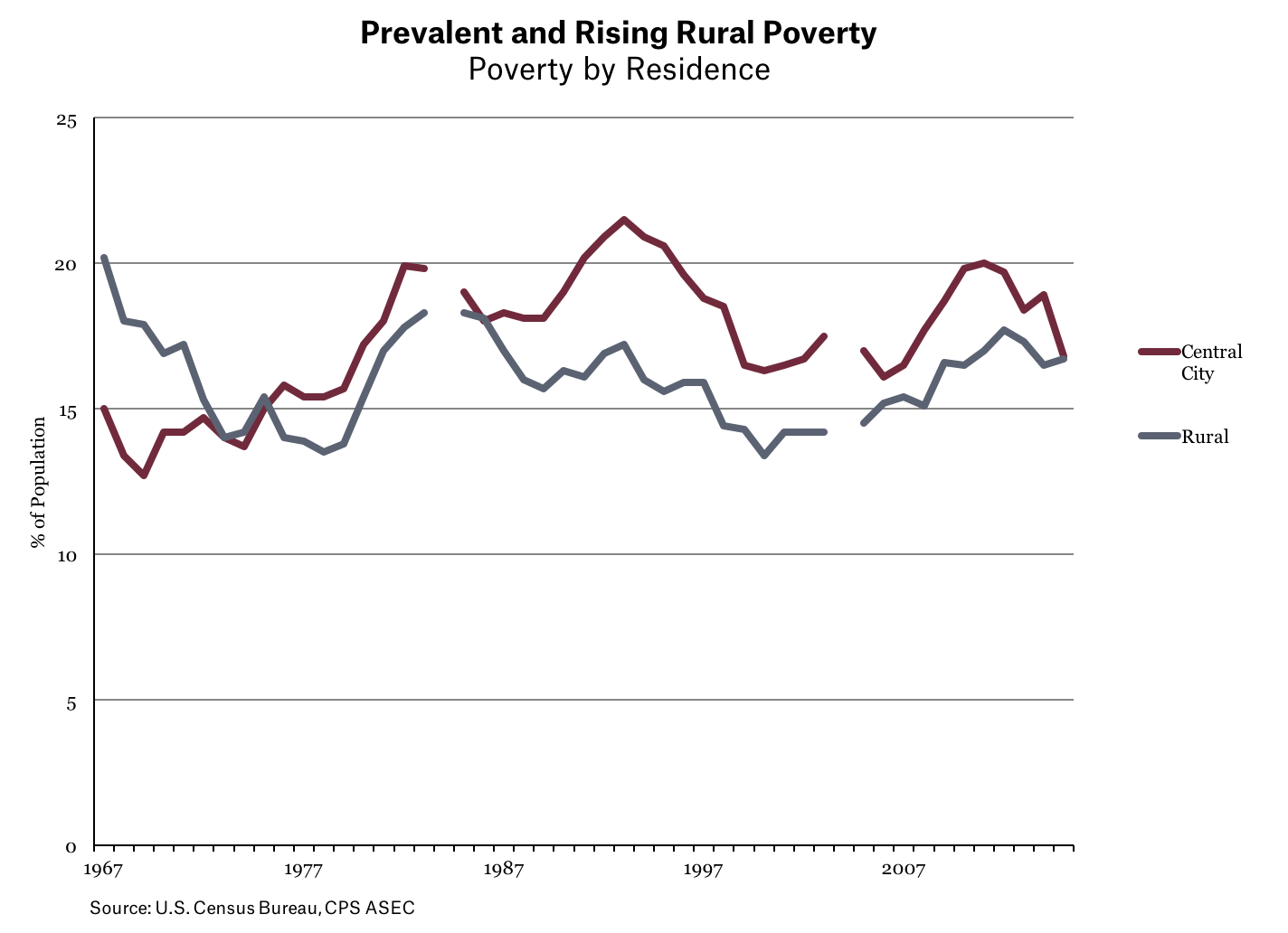

And although poverty often is thought of as an urban problem, rural America also has high poverty rates, close to that of central cities.

Spending on Poverty

Although some critics argue that anti-poverty spending has skyrocketed, the long-term trend of federal spending on low-income people (not including health care) is stable when measured as a percentage of the total economy. Discretionary program spending did rise during the Great Recession but is falling back towards its long-term trend of two percent of GDP.

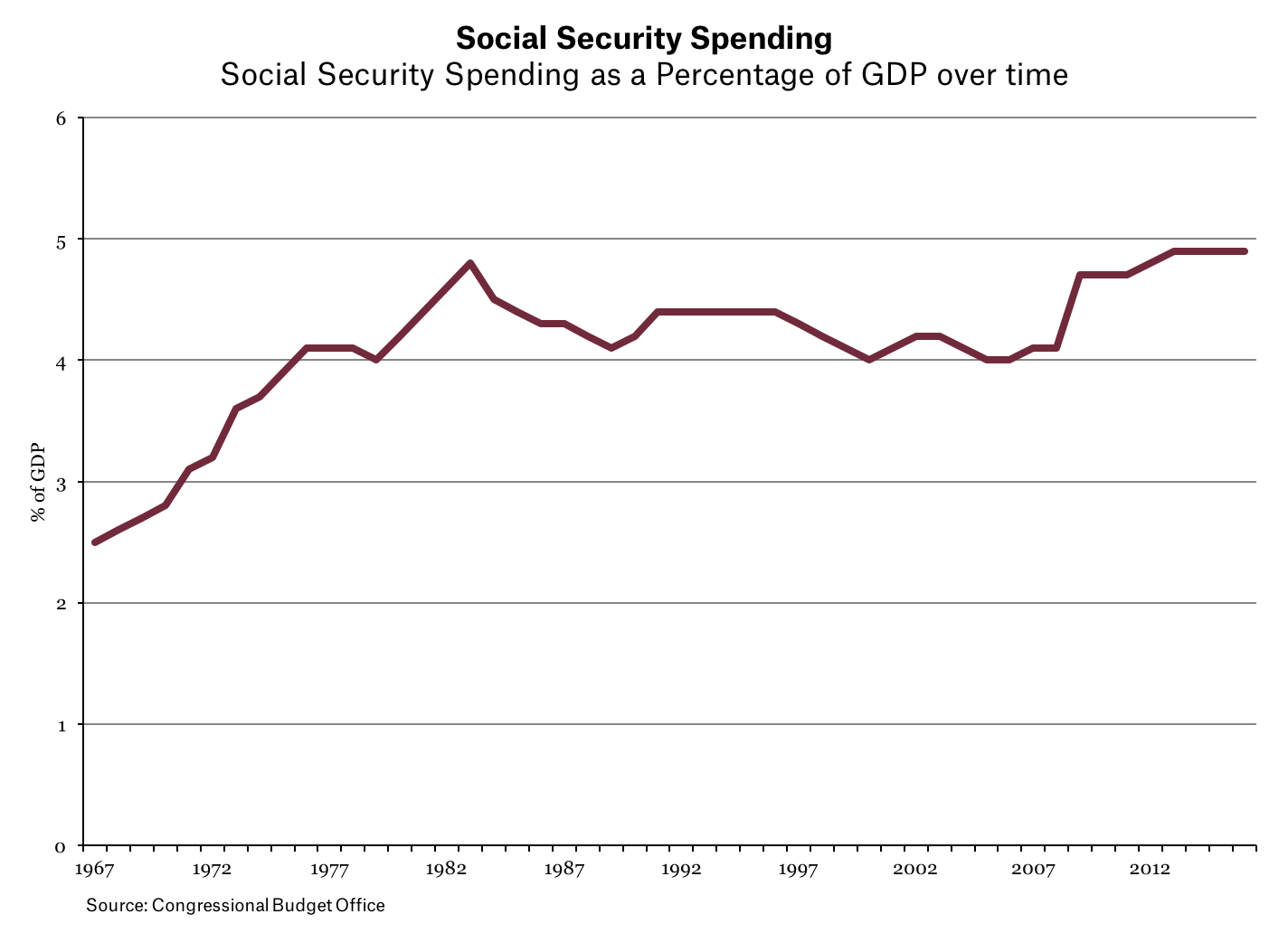

As noted earlier, the single most effective government program fighting poverty has been Social Security. Spending rose in the 1960s and again in the 1970s, sharply reducing poverty rates among the elderly, which fell from 35 percent in 1960 to 10 percent in 2014. Social Security spending for the non-elderly reduced that group’s poverty by 8.5 percent in 2012.

Although critics argue that programs for low-income people take a disproportionate share of the federal budget, in fact they are modest. Economic security programs represent only 14 percent of all federal domestic discretionary spending, which is turn is only 16 percent of the total federal budget. This means that discretionary economic security programs are only 2.2 percent of overall federal spending.

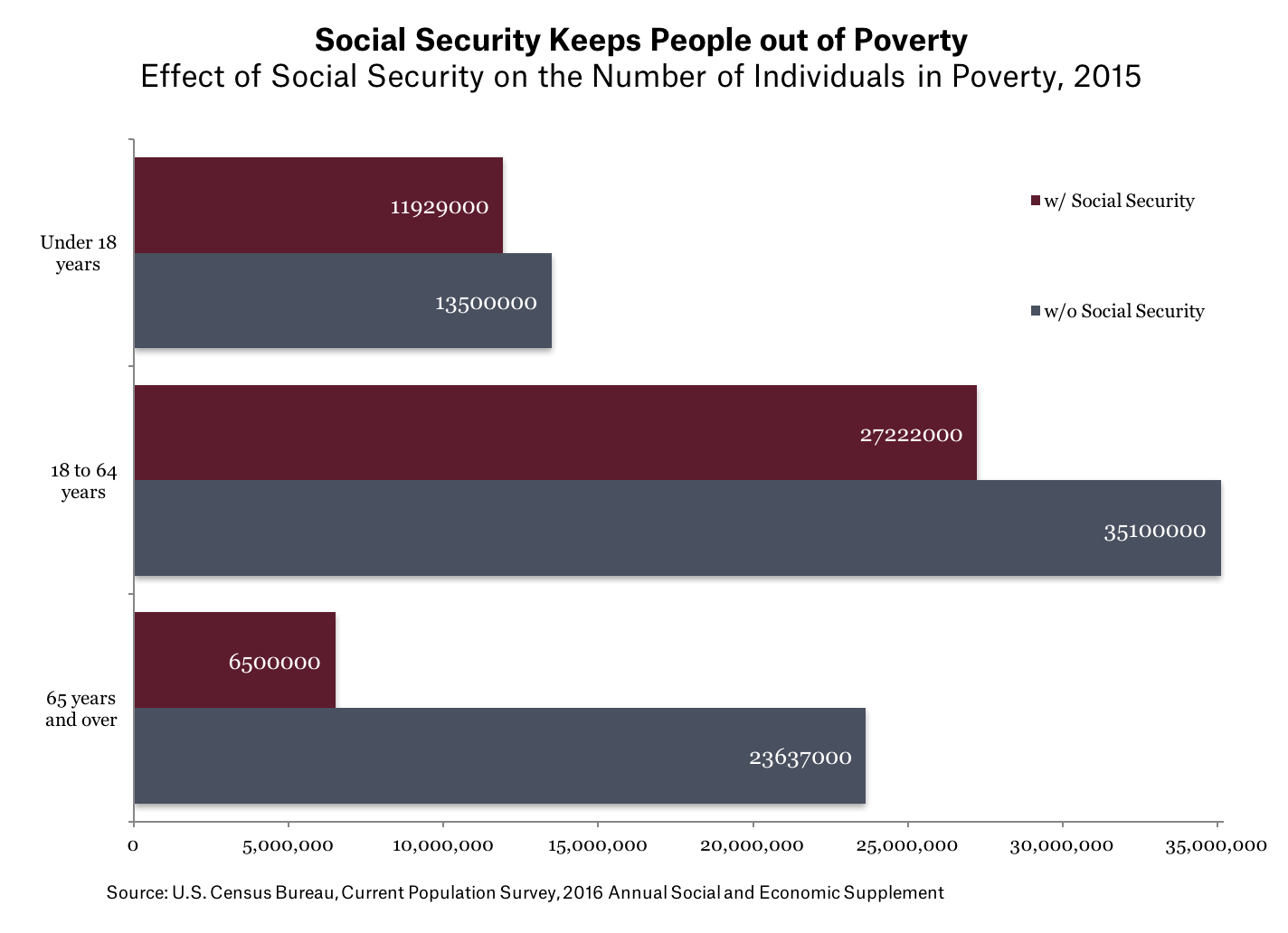

The relative stability of the poverty rate has led some critics to assume that government spending has no impact on poverty. But this is wrong. Without these vital programs, many more people would fall into poverty. Social Security, both the old age and disability programs, has the biggest impact. Without Social Security, the overall supplemental poverty rate would have been 8.3 percentage points higher and the poverty rate for older Americans would have been 49.7 percent. Social Security has kept 26.2 million individuals out of poverty.

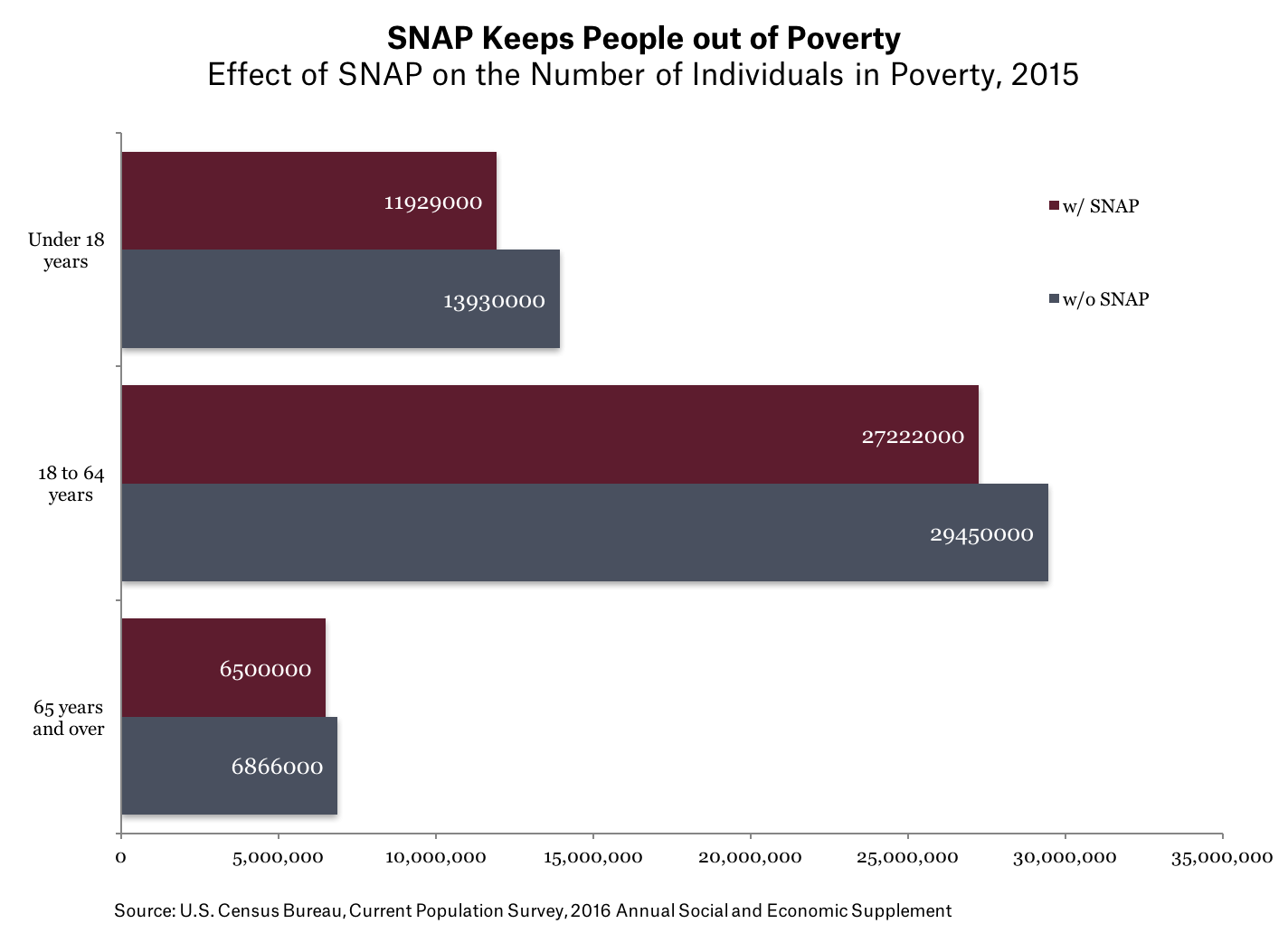

Social Security is not the only program with a substantial anti-poverty impact. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as Food Stamps) relieved 4.6 million people from living below the poverty line in 2015. A large majority of people using nutrition assistance is either employed, too young to work, over 65 years old, or disabled.

Government programs have had a substantial impact on fighting poverty. According to one estimate, when the effects of government programs are put into poverty measurement, programs now are cutting poverty “nearly in half” compared to only a one percent reduction in 1967, with the impacts especially strong for child poverty. Over two-thirds of Americans who were between the ages 14 and 22 in 1979 got some type of government income support between 1978 and 2010.

Weak Incomes and Inequality are a Major Contributor to Poverty

Focusing on government programs should not distract us from the bulwark maintaining poverty—good, well-paying jobs. Anti-poverty programs can only do so much in the face of stagnant incomes and historic levels of inequality. Changing the rewards to work is essential for reducing poverty.

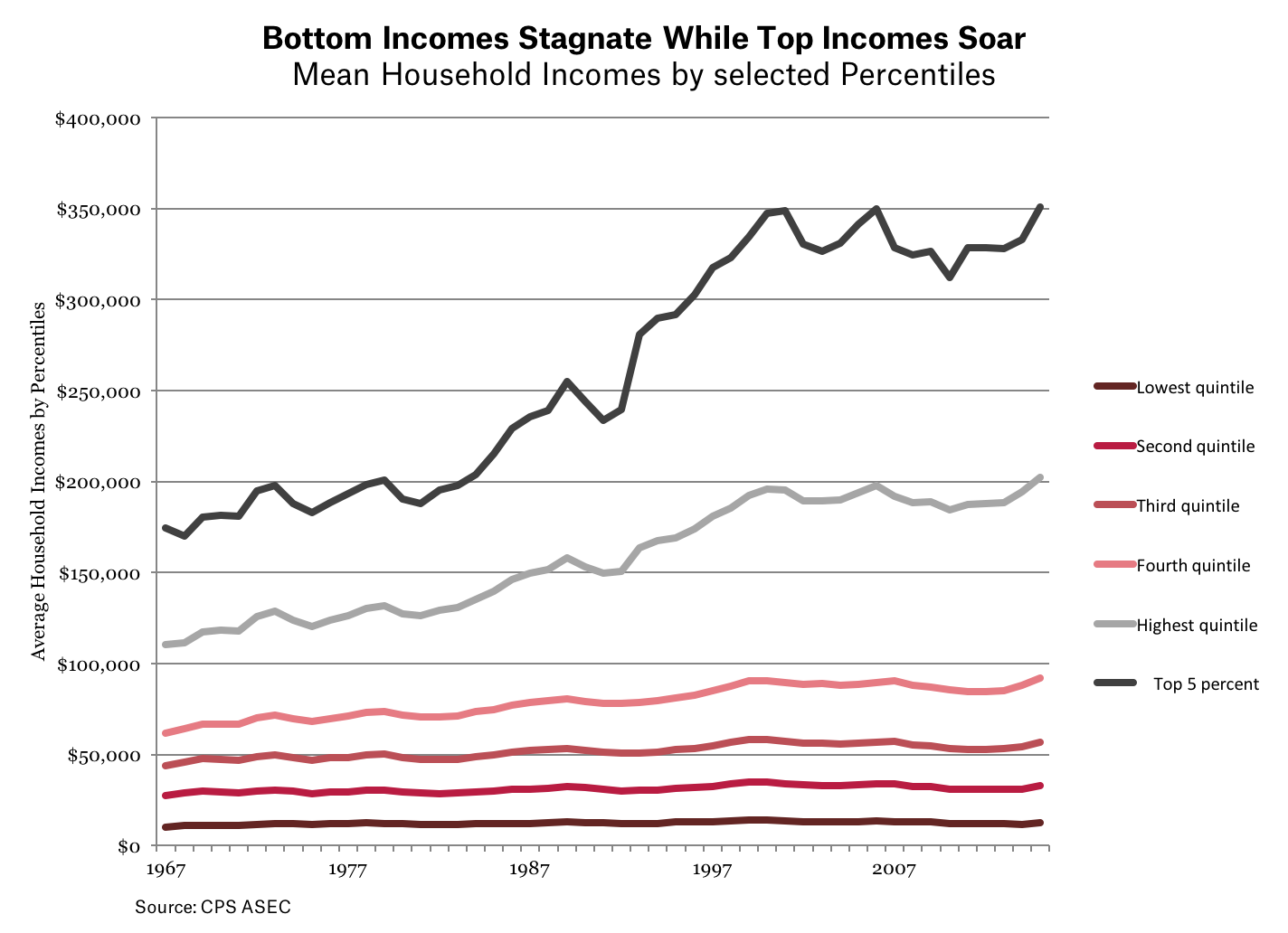

Household income adjusted for inflation has grown relatively slowly for most Americans. Between 1967 and 2016, American real Gross Domestic Product grew by 282 percent, while median income only grew by 21.2 percent, and income for the bottom ten percent grew by 21.8 percent, an average of less than one-half of one percent per year. Such slow income growth will not reduce poverty, or help middle-class households get ahead.

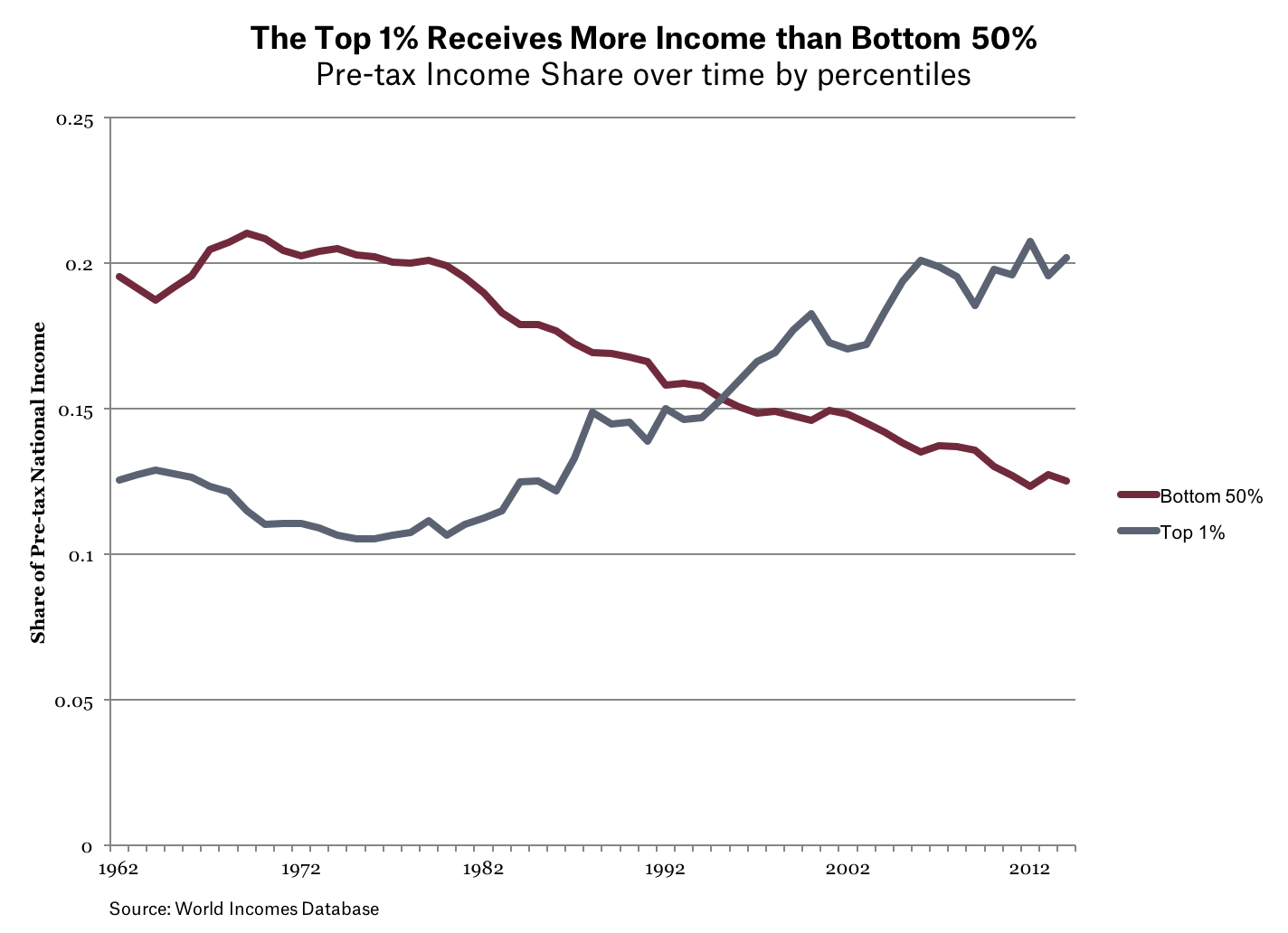

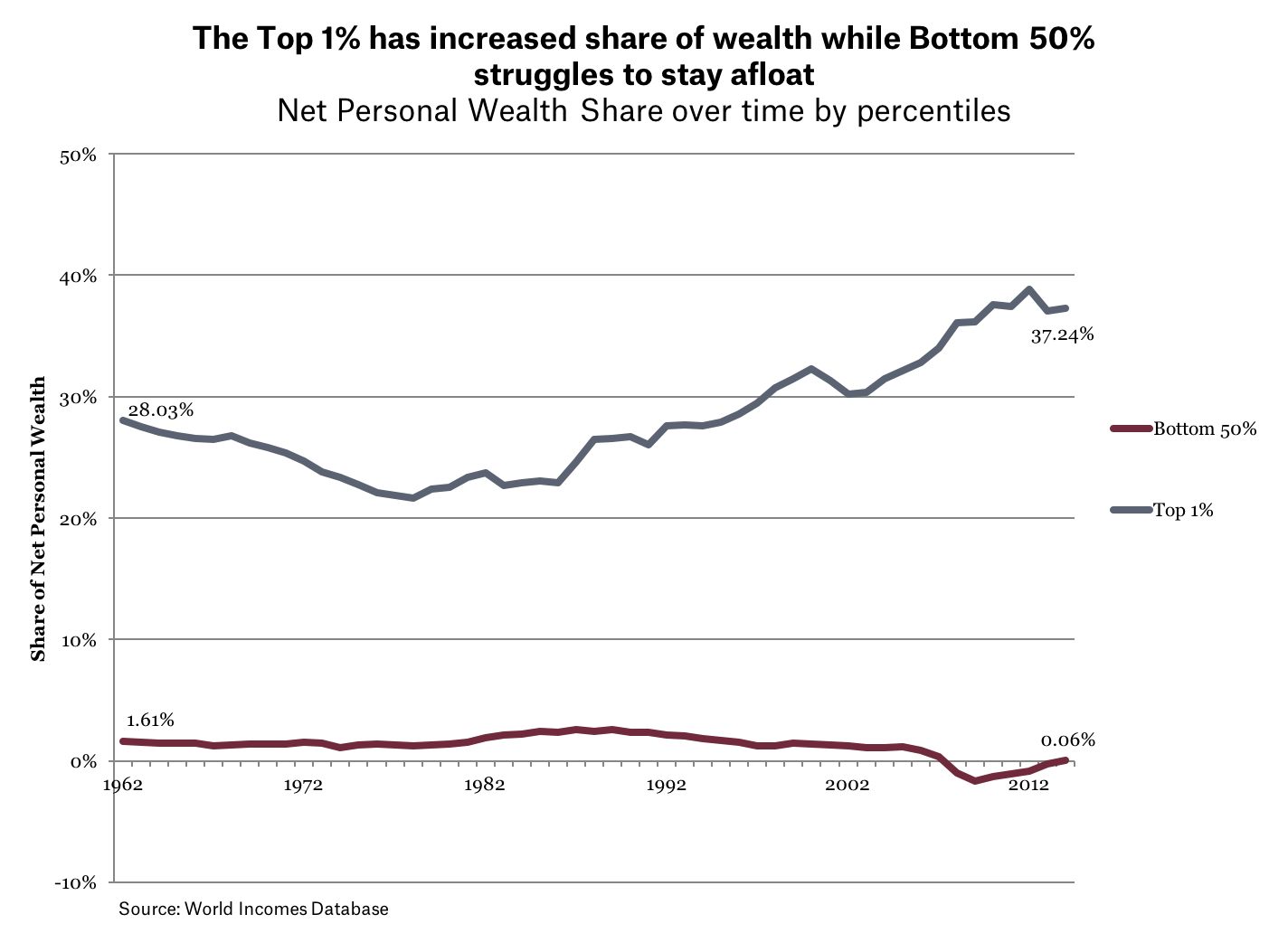

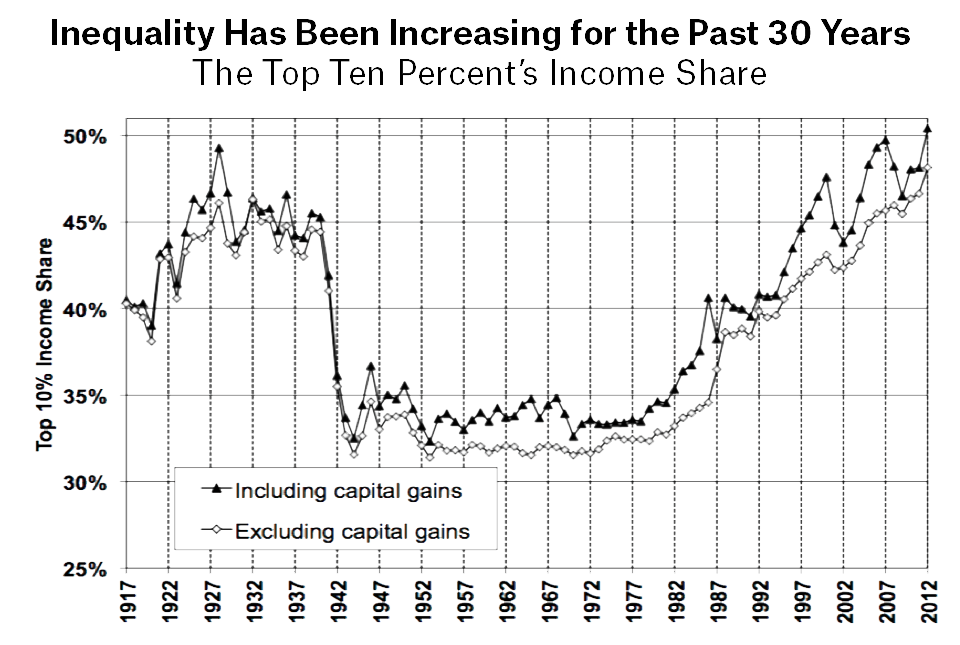

Inequality has steadily increased over the past 50 years. This is reflected in stagnating incomes for the bottom 60 percent of earners while the top 5 percent has enjoyed substantial incomes. As of 1995, the top one percent share of income has exceeded to share of income for half of all Americans. Inequality in wealth has also been steadily increasing, particularly for the past 30 years.

Although many factors have contributed to slow income growth, stagnant wages are a main cause. And for poor people, wages have been low for a long time. The federal minimum wage has lagged well behind inflation, with its real value peaking at $8.68 per hour in 1968. Currently, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is sixteen percent the real value of 49 years ago.

A single person who worked full-time at the federal minimum wage would have an income below the poverty level, and if they had children, their poverty would be even more severe. (The real value of the MW peaked in 1968.) Many anti-poverty programs—nutrition assistance, housing, tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and Medicaid—help support poor working families.

The reverse of stagnant wages and household incomes has been a dramatic rise in inequality, especially for the top one percent of household incomes. Inequality in the United States has reached historically high levels not seen since the “Roaring Twenties,” just before the Great Depression.

Source: Saez 2016

Is Poverty Mismeasured?

One critique of poverty data argues that poverty is not as bad as it seems, given basic household living standards. This analysis argues that those measured as in poverty “are not actually poor in any ordinary sense of the term,” because most poor households are not “near destitution,” and the “average poor household has many modern conveniences” (such as air conditioning, mobile phones, a microwave oven, a color television, or a car).

But other analysts also have considered whether the official measure overstates poverty, because it is based only on cash income for households, not the net value of anti-poverty program benefits. To analyze this, economists have created a “Supplemental Poverty Measure” (SPM) that adds the value of non-cash benefits such as food stamps, housing subsidies, and school lunches, and subtracts necessary costs such as taxes, expenses related to work, child care, and out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Although the SPM and the official poverty rate differ for some groups of the population, by and large the two rates tell the same story. In 2015, the official rate for all people was 13.7 percent compared to 14.3 percent using the SPM. Poverty for children under 18 years old was seen to be lower, largely due to the value of school programs and the lack of costs for work.

But using the SPM for adults found higher poverty rates, especially for the elderly. For those 18 to 64 years old, the SPM was 1.4 percent higher than the standard measure, and for those over 65, it was 4.9 percent higher, an over 50 percent increase. So using an alternative poverty measure does not result in less measured poverty, and for many people, it shows higher poverty.

Other analysts have used data from administrative records and combined it with official income survey data. One of these studies found that using administrative records shows higher benefit use than reported in surveys, meaning that overall poverty rates would be “markedly lower.” But that is because “the effects of government programs in reducing poverty are sharply understated.” Contrary to those who say anti-poverty programs don’t work, this line of research supports other findings that show measured poverty would be much higher without government anti-poverty programs.

So, alternative poverty measures often result in higher poverty levels, not lower ones. And while using administrative records shows overall higher levels of household well-being, that finding indicates that anti-poverty programs work.

Conclusion

Poverty remains a vexing problem in the United States. It is unequally distributed, with people of color and women suffering higher poverty rates. But it also cuts across all Americans—black, white, and Latino; urban and rural; men and women; children, working-age adults, and the elderly.

Poverty is driven primarily by inadequate incomes and economic opportunities. Wages and incomes have stagnated for the majority of Americans, dragging some down into poverty. Extreme inequality of income and wealth contributes to poverty, both immediately and by affecting the life chances of children—the children of the wealthy have a much better chance of success than a child raised in poverty.

Anti-poverty programs have kept millions of Americans out of poverty. Contrary to what some critics claim, government spending has been very effective at reducing poverty for a variety of groups. But government programs cannot by themselves substitute for a more robust economy with fair and equal opportunities for all.

Poverty is multidimensional. Although this report has focused on economic poverty, it radiates into housing, health, education, criminal justice, and upward mobility, which in turn affect economic poverty. During the coming year, we will analyze these interactions in more detail, to document how much poverty hurts all Americans, and why the nation needs a broad, robust campaign to attack poverty.

In his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” Nowhere is this more true than with poverty in America.

Sources and Notes

(In Order of Introduction)

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC). 2016. For information on confidentiality protection, sampling error, nonsampling error, and definitions, see www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/techdocs/cpsmar16.pdf

- Brundage, Amy, and Jessica Schumer. The War on Poverty: 50 Years Later (2014): Obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. Web.

- Greenstein, Robert, Richard Kogan, and Isaac Shapiro. 2017. “Low-Income Programs Not Driving Nation’s Long-Term Fiscal Problem: Programs Outside Health Projected to Decline Relative to Economy.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). (21 February, Web)

- Wimer, Christopher, Liana Fox, Irv Garfinkel, Neeraj Kaushal, and Jane Waldfogel. “Supplemental Poverty Measure.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of World Poverty (2013): Web

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2017. “Historical Budget Data.” (January, Web)

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2016. “A Closer Look at Discretionary Spending.” (January, Web)

- Renwick, Trudi, and Liana Fox. 2016. “The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2015.” U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. (13 September, Web)

- Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2017. “Gross Domestic Product.” (30 March, Web)

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC). 2016. “Table A-2 Selected Measures of Household Income Dispersion: 1967-2015” (https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-inequality.html)

- World Wealth and Income Database. 2017. (Web)

- Saez, Emmanuel. 2016. “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” UC Berkeley. (June 30, Web)

Unfortunately, yet another war that LBJ started, but didn’t do very well at, nor finish. LBJ wanted to be FDR, but wasn’t.

Today most government wars are … manipulation of statistics, starting with LIBOR. Info wars of deception and psyops.

At least LBJ wanted to emulate FDR. These days, nearly all of our politicians want to emulate the most venal and greedy of former leaders. Today’s politicians are only intent on tearing down the last few remaining shreds of FDR’s New Deal. I wish we had someone around like LBJ these days, flawed as he was.

There are 2 as far as I can tell – Bernie Sanders and Tulsi Gabbard, and the latter is a political neophyte.

Was talking to some organized labor friends the other day about 2018 and 2020. Elizabeth Warren came up. A grizzled 54-year old man rolled his eyes.

“We don’t need moderate 1950s Republicans from the Ivy League. Where the fuck is FDR?”

We talked about the Overton Window moving inexorably to the right for 50 years. We talked about neoliberalism, NAFTA, GATT, TPP, TTiP, the EU, how globalization hurts all but the investment class…

Strangely, didn’t hear one racist or sexist comment. Clinton didn’t even come up.

A solitary report from the hinterland, but it is what it is.

As someone who actually knows people in poverty and has lived in poverty, this (along with every other poverty measure I’ve seen) is ignoring a rather large elephant in the room: interest payments. When you’re poor, neither income nor expenses are stable or predictable, so you almost certainly wind up in debt at some point, often for your entire life. Because you likely have poor credit, those interest payments are likely very, very high. Credit cards, medical debt, student debt (people in poverty are prime marks for for-profit colleges), payday lending, etc. Billions of dollars of corporate profits come directly out of the paychecks of poor people every year, and then there’s our law enforcement system…

And in addition to interest payments, lets not forget that the nature of financial services poor people have access to also mean that even your most basic transactions (e.g. cashing a paycheck) come with hefty fees themselves. It’s death by a thousand cuts, even if you do find steady work.

Yes, and another thing… people I know who rely on benefits spend an huge amount of time managing and navigating unresponsive and inefficient bureaucracies, jumping through inane hoops, sitting in waiting rooms, making phone calls, filling out forms and correcting errors made by those bureaucracies. It’s not like, if you’re poor you get money without effort. Not as big a deal as interest, but another rather large tax on the poor.

yup. I keep thinking of other things too, but don’t want to hijack the thread more than I already have. Curious what other unstated poverty taxes the readers here can come up with. Guessing it’ll be a rather long list.

Here’s another from propublica: up to 30% higher car insurance rates. Now I’m really curious what poverty rates would look like if we added all the hidden taxes as well as the benefits (with maybe a cost of living adjustment to boot – poverty in the bronx is a wee bit different than in rural Alabama, no?).

and if you don’t have a working car, using public transportation to get back and forth between your home and 2 or 3 jobs is a huge tax on time. not to mention the other places you have to go, such as the grocery store or the doctor.

Yes, the inane hoops and difficulties of obtaining any govt assistance is overwhelming. Just the other day someone I know started ranting and whining about welfare “cheaters” and how poor people have it “so good” and they figure out how to rig and game the system. I’m certain that there’s an amount of rigging and gaming going on, but the poor people I know are living on the edge and it’s remarkably difficult to obtain the benefits that they are eligible for.

For those that work, it’s even more difficult to find the time to go to govt offices – often not in the most convenient of locations or even on public transit lines – to jump through the hoops to get what paltry benefits exist.

It amazes me how so many citizens still buy the myth that poor people really are these “lucky duckies” who’re living large on the dole. Not. Really.

those lucky duckies who are really living high on the dole are the top 10% er’s . They don’t get rich by paying their fair share.

Agreed. And I say it as often as I can, but the propaganda about how “teh poorz is ripping you off bigly” still resonates so strongly with most US citizens.

I find that, even when I finally (!!) find someone who’ll agree with me that the top 10% or at least the top 1% are who’re really on the dole (so to speak) and ripping us all off… these same people almost never fail to circle back and start whining about the poor.

The propaganda demonizing and stigmatizing the poor and undocumented people has been very very effective. Hard to find someone who really gets that it’s not the poor who are the “problem.”

Well, as one of those lucky people in the top x%; the theft of my time by numerous business relationships is infuriating. I can’t imagine….

Time aint $, it’s ours. It’s quality of life.

I fully believe the “poors” are paying 3x or more time-tax than I. Waiting rooms; esp associated with the legal system, userous banksters, clinics, anything saftey-net related, etc.

Then the finances:

Higher interest, greater fees , certainly in proportion to income, and possibly in sum total. I.e I never pay a western union fee, pawn shop usury rate or fee, a check-cashing fee, a $400 ticket for “manner of walking”, fees for ankle bracelets, fees for fees, the service fees for the fees, and the paper billing fee, etc. It’s disgusting.

High interest rates is definitely a big cost for the less well off who need to get credit to get by. The worse your credit score the higher the rate, so this is a very valid point.

I would also add junk fees which can make even the punitive rates a lesser cost in terms of the overall percentage of principle advanced. I’m writing a post which touches this point so hopefully I’ll be able to expand on it in the near future. Not wishing to give a spoiler, it’s not just consumers who suffer — business is starting to see negative consequences too.

I have been listening to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, and your comment reminds me of Smith’s aversion to monopoly. The Navigation Acts were an attempt to protect English trade by building systems of monopoly, ensuring the profits of English merchants. He argues that this is shortsighted, and in the long term counterproductive to the true wealth formation of the nation. True wealth is formed by the industry of it’s inhabitants, continually dedicated to the improvement of both its manufactures and the natural environment. The continual improvement of land and produce is key. Granting privileges to a select few, while extremely profitable, is detrimental to this improvement process and in the long term leads to decline.

Smith also seems very critical of people who put their own interests above that of the nation or the common interest. A strong and wealthy nation is good for all by definition.

Saving the banks at all costs, and the short sightedness of the financial industry in maintaining a monopoly on money creation in order to ensure massive profits for the few will destroy the country. Only those so self-absorbed in their plundering cannot see the dangers.

People are waking up to the fact that monopolistic corporations don’t bring prosperity to the nation.

John Scalzi seems to cover most of the bases, I wonder what the numbers would be using his definitions.

I think that our culture’s emphasis on education through high school and college comes, to a significant degree, at the expense of developing strong work ethics. Being able to work long hours at manual jobs kept many a family going through the ’60s and ’70s. The message kids get today is that ‘you can’t have a part time job, because you have all this schoolwork’. I think this leaves them with poor preparation for life.

I do not have the world’s greatest manual work ethic. I’m always trying to increase my ability to do manual labor. It’s a struggle. But the work ethic of the typical kid coming out of high school these days is terrible. Too much homework. Too many video games. Not enough learning how to do.

Technology is changing so fast that it is hard to see how the vocational education one receives in school can be relevant for very long.

I agree. I live in a college town that is just an hour’s drive from Mexico. The work ethic of youthful Mexicans puts their American counterparts to shame.

And I would say that you are looking at the past through neoliberalism-colored glasses. It was not “being able to work long hours at manual jobs” that kept many a family going through the ’60’s and ’70’s – it was actually the strong unions and the availability of manufacturing jobs that improved the economy then. There was actually a steady decline in work hours in the ’60’s and ’70’s.

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/hours-of-work-in-u-s-history/

And I would remind you that college enrollment rates rose dramatically during the 60’s and 70’s, far more than they are rising today, not because children are lazy, but because parents realized the value of an education for their children.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/183995/us-college-enrollment-and-projections-in-public-and-private-institutions/

I wouldn’t even say it was the manufacturing jobs. Remember, it was only about two generations ago when manufacturing jobs were regarded as the third circle of hell. So brutal, dangerous, and demoralizing that people preferred the romance of homesteading and agriculture, which was PREVIOUSLY the third-worst job you could have, next to pre-industrial mining and soldiering in certain countries.

Manufacturing was never the creator of non-bourgeois prosperity. That would be unionization. Unionization is why a job sector that had Upton Sinclair sincerely comparing it to chattel slavery somehow made this THE path to the American Dream. Which is why it amuses and frustrates me to see people wringing their hands in despair at the coming post-industrialization.

Wow. I got sucked right into that thinking. dang.

thanks for that.

oh, the glory days of only working 40 hr weeks around molten steel!

My brother-in-law just retired last year after 39 years of the steel mill. What a waste of a creative man. He had a fish tank that filled one whole side of a room, doing it all himself, and with the knowledge to keep it going with the right stock for years. I suggested he try to contract with elite offices, restaurants, and so on, to develop it into a business. He was also a skilled organ and piano player with an ARCT (Associate, Royal Conservatory of Toronto), and could have been a professional musician.

But he had grown up in a home with an unstable income, and had been taught that job security was everything, so, the mill. Fortunately, his was not the one in Hamilton that closed.

Why do you apparently assume that his job at the steel mill was a “waste”? It’s honest work – your brother-in-law could go home tired each day knowing that he made something out of nothing, the steel that makes cars, bridges, wire, fencing, etc. etc. Don’t you think his job is more satisfying than being an office drone?

Also, the income he made working allowed him the joys of creative avocations that because he practiced them for pleasure and not for income, were more rewarding also.

I think you have it exactly backwards.

Bingo

I grew up in the South, where there were no unions. It wasn’t uncommon in the ’60s and ’70s for people to have two nearly full time jobs, or to work back to back shifts. That may not seem reasonable, either, but they learned to do things. Sixteen year olds drove the school buses.

College enrollment rose so much during the ’60s and ’70s because government and big business arbitrarily decided that the better, white collar, jobs required a four year degree. This was also partly the result of Griggs vs. Duke Power (1971). The bachelor’s degree requirement raised the value of the four year degree because it restricted the supply of labor, much like unionization did elsewhere.

Humans have a poor understanding of time. If starting a real job gets pushed back to one’s mid-twenties and one retires from that career–after switching companies a number of times–by one’s mid-fifties, the ratio between the cost of one’s education and one’s future earnings becomes much, much less favorable, and this is without considering the likely diminishment of one’s 401-k because of vesting requirements, the necessity of borrowing money from it to fund transitions, etc.

It is my opinion that all the kids going to college because society says, ‘you have to go in order to get a good job,’ are going to be disappointed in their job prospects and their debt burdens when they get out. As one of my college friends, who got a Phd in Molecular Biology and now operates a dog training business, said, [I paraphrase] ‘Learn how to do something useful, like welding, and think great thoughts while you weld’.

The issue here is the availability of worth while work for kids. My first job when I was 12 was throwing an afternoon paper route which included monthly collection: very educational. After that I flipped burgers at Burger King: another education. Then a few years working at a boat yard: a great education. That overlapped with a morning paper route. All between ages 12 and 18.

All of those jobs are now done in the same locations by men and women in their 30s and 40s. Those men and women should have good paying, living wage jobs that support their families aspirations rather than crap teenager jobs that provided me a very useful early education on power asymmetries and pocket change while I was in high school.

There is no work ethic where there is no work and the most optimistic and energetic people learn what NeoLiberals call “lazyness” and I call “resource efficiency” by only being offered crap jobs for crap wages.

You don’t know how right you are with the too much homework. In college I didn’t sleep 3 nights a week much less work during my senior year because all I did was homework. Every class in highschool that had homework optional I got straight A’s and never did homework. Finland doesn’t have homework and they have the best schools in the world.

I say the above in the context of ‘Hillbilly Elegy’. The author says that many people in his hometown believed that they were hard workers, when not one of them worked more than twenty hours a week.

Hillbilly Elegy is a blame the victim framing of the end result of 40 years of crappification of work.

Give those people meaningful work that pays enough for them to materially improve their lot and you’ll be astonished at what new motivation they bring to their work.

That was the lesson of the Clinton boom ( though I despise Bill) that increased the labor participation rate to an all time high: this was the only moment in the NeoLib era when working hard actually paid off at all for working people.

“The federal minimum wage has lagged well behind inflation, with its real value peaking at $8.68 per hour in 1968.”

The federal minimum wage was $11.20 per hour in today’s money — according the BLS online inflation calculator which uses the most commonly accepted inflation measure, CPI-U.

https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=1.60&year1=1968&year2=2017

This is a serious “marketing” error when we are trying so desperately to convey that per capita income (or what have you) doubled since 1968 while the min wage dropped $4 — making it that much more undeniable that today’s $10 per hour jobs which are sort of the dark glass ceiling in today’s unskilled job market can easily become $20 with collective bargaining …

… which latter phrase along with the words “labor union” fail to appear anywhere in today’s typical blinders on or whatever the problem is essay on poverty.

Thought just occurring to me:

If the bottom 45% of earners now take 10% of overall income instead of 20% like in 1968 — and — that is half of twice as much overall income, then, the bottom 45% are right back where they started from in absolute terms (on average of course: less at the bottom/more at the top).

If the next 54% up now take the same 70% of overall income as they did 50 years ago — but– that is of double the overall income, then, they have twice what they started with in absolute terms (on average of course: less at the bottom/more at the top).

If collective bargaining by the 45% can raise prices on the 54% so they give up 10% of overall share — which means losing 14% of their share — they will still end up with 172% of what they started with in 1968 in absolute terms.

To get that absolute 28% back from the top 1% …

… who now take 20% of overall income instead of 10% like before — which means double the share of doubling per capita income — which means 400% of what the top 1% took in 1968 in absolute terms (on average of course: less at the bottom/more at the top) …

the 54% cannot do so by raising the price of burgers. More direct means will be necessary — more like the tax ax — like the death tax to use one currently operating example.

When I was a kid in the 50s, the top federal income tax rate was (theoretically at least) 92% on incomes over one million dollars (today’s money — close enough I think). The president of the United States was a five star general Republican who was not in too huge a hurry to do anything about American Apartheid. IOW, should be nothing too alien (if that scares) about confiscatory taxes in today’s culture.

CEOs and quarterbacks now take home 10X more than is needed to get them to show up and work productively. When enough union density is built up tax axing this should not be a problem. In the 60s the top paid NFLer Joe Namath made $600,000 in today’s money. Double that for doubled productivity (or what have you) and you still get only one-tenth of what Chicago Bears’ Jay Cutler gets.

[cut-and-paste]

Not to mention other ways — multiple efficiencies — to get multiple-10%s back:

squeezing out financialization;

sniffing out things like for-profit edus (unions providing the personnel quantity necessary to keep up with society’s many schemers;

snuffing out $100,000 Hep C treatments that cost $150 to make (unions supplying the necessary volume of lobbying and political financing;

less (mostly gone) poverty = mostly gone crime and its criminal justice expenses.

IOW, labor unions = a normal country.

FRED shows the real minimum wage did peak in 1968.

https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2015/07/the-real-minimum-wage/

You can set its “real value” indexing from any point in time: current $, 1960s value of $, even the 1900 value of $, although inflation stats that far back are pretty dodgy. You are incorrect in suggesting that the only way to run a “real value” is comparison to current dollars. All it means is adjusting for inflation.

There is still a war on poverty? I thought it got trumped by the war in Viet Nam, and was pretty much over by 1980. It certainly was not fought with half the vigor of the Viet Nam war. Looking at these graphs does not change my mind about that. Our awareness of growing inequality may renew our efforts to reduce poverty. At least minimum wages are going up.

I think it is dangerous to make assumptions about how much money people need to get them to show up at work, just as it is dangerous to decree that it’s bad for society to have twenty three different kinds of deodorant. Does that make me a neoliberal?

It’s also dangerous to assume that marginal tax rates are the same as effective tax rates. The danger in Bernie’s tax program (which Hillary largely adopted in the last few months of her campaign) was that its effective tax rates were by far the highest in American history. His intention was to use that enormous increase in taxes to provide dubious public goods, like free college and free healthcare. I’m all for healthcare, and want a system that is more equitable than the one we’ve got, but I think that the move towards socialized healthcare in the past decade has diminished the quality of care.