Yves here. While you were busy watching Trump and the Middle East, and maybe Brexit and China once in a while, some supposed neoliberal success stories are likely to be anything but that.

By lan Cibils and Mariano Arana, Political Economy Department, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Originally published at Triple Crisis

In Argentina’s 2015 presidential run-off election, the neoliberal right-wing coalition “Cambiemos” (literally, “lets change”), headed by Mauricio Macri, defeated the populist Kirchnerista candidate by just two percentage points. Macri’s triumph heralded a return to the neoliberal policies of the 1990s and ended twelve years of heterodox economic policies that prioritized income redistribution and the internal market. The ruling coalition also performed well in the October 2017 mid-term elections and has since begun implementing a draconian set of fiscal, labor, and social security reforms.

One of the hallmarks of the Cambiemos government so far has been a fast and furious return to international credit markets and a very substantial increase in new public debt. Indeed, since Macri came to power in 2015, Argentina has issued debt worth more than $100 billion. This marks a clear contrast to the Kirchner administrations, during which the emphasis was debt reduction.

The Kirchner Years: Debt Reduction?

Both Néstor and Cristina Kirchner pointed to desendeudamiento—debt reduction—as one of the great successes of their administrations. To what extent was debt reduced during the twelve years of Kirchnerismo?

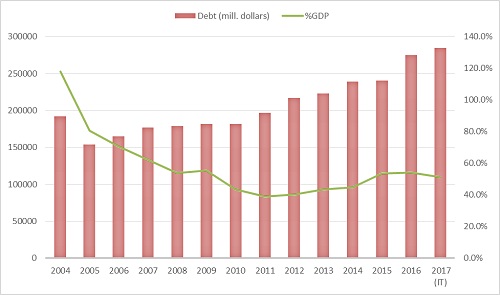

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Argentina’s public debt stock and the debt/GDP ratio between 2004-2017. One can see that there was a substantial reduction in the debt to GDP ratio between 2004-2011—the first two Kirchner terms—due primarily to: a) the 2005 and 2010 debt restructuring offers, b) a deliberate policy of desendedudamiento (debt cancellation), and c) high growth rates. Indeed, debt/GDP dropped from 118.1% in 2004 to 38.9% in 2011. One can also see that the actual stock of public debt fell after the 2005 debt restructuring process, and then remained relatively stable until 2010. In 2011, it began a slow upward trend, due to the re-appearance of the foreign exchange constraint once the commodity bubble burst and capital flight increased.

Figure 1: Public Debt Stock (millions of dollars) and Debt/GDP ratio

Source: Ministry of Finance, Argentina.

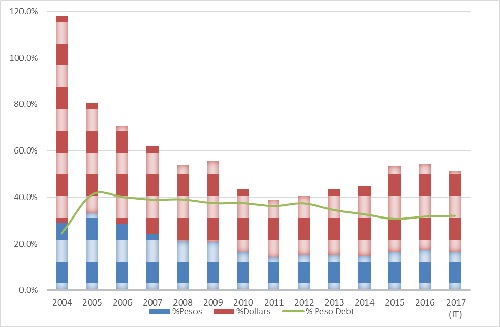

An additional, fundamental change occurred during the first two Kirchner administrations: the change in currency composition of Argentina’s public debt. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, peso-denominated public debt reached 41% of total debt after the 2005 debt-restructuring process. Between 2005 and 2012 it remained relatively stable, and then, after 2012, dollar-denominated public debt began to grow again although never reaching pre-2005 debt-restructuring levels. The currency composition change is key, since it reduces considerably the pressure on the external accounts.

Figure 2: Currency Composition of Argentina’s Public Debt (as a % GDP)

Source: Ministry of Finance, Argentina.

Fast and Furious

Since Macri became president in December 2015, there has been a dramatic change in official public debt strategy, radically reversing the process of debt reduction of the previous decade. As shown in Figure 1, there was a substantial jump in the stock of public debt in 2016, and it has continued to grow in 2017.The result to date has been a substantial increase in the stock of Argentina’s dollar-denominated public debt, as well as an increase of the debt service to GDP ratio. New debt has been used to cover the trade deficit, pay off the vulture funds, finance capital flight, and meet debt service payments. All of this has resulted in growing concerns about Argentina’s future economic sustainability, not to mention any possibility of promoting economic development objectives.

Upon taking office, the Macri Administration rapidly implemented a series of policies to liberalize financial flows and imports, and a 40% devaluation of the Argentine peso.[1] In this context, it also went on a debt rampage, increasing dollar denominated debt considerably. Between December 2015 and September 2017, Argentina’s new debt amounts to the equivalent of $103.59 billion.[2] This includes new debt issued by the Treasury (80%), provincial governments (11%), and the private sector (9%). While Argentina’s debt had been increasing slowly since 2011, the jump experienced in 2016 was unlike any other in Argentina’s history.

If the increase in debt is alarming, the destination of those funds is also cause of concern. Data from Argentina’s Central Bank (Banco Central de la República Argentina or BCRA) show that during the first eight months of 2017, net foreign asset accumulation of the private non-banking sector totaled $13.32 million, 33% more than all of 2016, which itself was 17% more than all of 2015. This means that since December 2015, Argentina has dollarized assets by approximately $25.29 billion.

According to the BCRA, during the same period there was a net outflow of capital due to debt interest payments, profits and dividends of $8.231 billion. Additionally, the net outflow due to tourism and travel is calculated at roughly $13.43 billion between December 2015 and August 2017.

In sum, the dramatic increase in dollar-denominated debt during the two first Macri years served to finance capital flight, tourism, profit remittances, and debt service, all to the tune of roughly $50 billion.

Where is This Headed?

Argentina’s experience since the 1976 military coup until the crash of 2001 has shown how damaging is the combination of unfavorable external conditions and the destruction of the local productive structure. The post-crisis policies of the successive Kirchner administrations reversed the debt-dependent and deindustrializing policies of the preceding decades. However, since Macri took office in December 2015, Argentina has once again turned to debt-dependent framework of the 1990s. Not only has public debt grown in absolute terms, but the weight of dollar-denominated debt in total debt has also increased. Despite significant doubts regarding the sustainability of the current situation, the government has expressed intentions of continuing to issue new debt until 2020.

What are the main factors that call debt-sustainability into question? First, capital flight, which, as we have said above, is increasing, is compensated with new dollar-denominated public debt. Second, Argentina’s trade balance turned negative in 2015 and has remained so since, with a total accumulated trade deficit between 2015 and the second quarter of 2017 of $6.53 billion. Import dynamics proved impervious to the 2016 recession, therefore it is expected that the deficit will either persist as is or increase if there are no drastic changes. Furthermore, in the 2018 national budget bill sent to Congress, Treasury Secretary Nicolás Dujovne projects that the growth rate of imports will exceed that of exports until at least 2021, increasing the current trade deficit by 68%.

Finally, according to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (October 2017), growth rate projections for industrialized countries increase prospects of a US Federal Reserve interest rate increase. This would make Argentina’s new debt issues more expensive, increasing the burden of future debt service and increasing capital flight from Argentina (in what is generally referred to as the “flight to safety”).

The factors outlined above generate credible and troublesome doubts about the sustainability of the economic policies implemented by the Macri administration. While there are no signs of a major crisis in the short term (that is, before the 2019 presidential elections), there are good reasons to doubt that the current level of debt accumulation can be sustained to the end of a potential second Macri term (2023). In other words, there are good reasons to believe that Argentines will once again have to exercise their well-developed ability to navigate through yet another profound debt crisis. This is not solely the authors’ opinion. In early November 2017 Standard & Poor’s placed Argentina in a list of the five most fragile economies.[3] It looks like, once again, storm clouds are on the horizon.

_______

[1] For details, see “Macri’s First Year in Office: Welcome to 21st Century Neoliberalism.”

[2] Observatorio de la Deuda Externa, Universidad Metropolitana para la Educación y el Trabajo (UMET).

[3] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/06/these-are-now-the-5-most-fragile-countries-exposed-to-higher-interest-rates-according-to-sp.html

‘What are the main factors that call debt sustainability into question? First, capital flight.’

Capital flees Argentina whenever the opportunity arises because successive governments — whether leftist or conservative — refuse to control inflation and maintain a stable currency.

Since 2001, the Argentine peso has slid from one-to-one with the US dollar to about 19 to the dollar today. With Argentine inflation running in the low to mid twenties (according to INDEC and Price Stats), the peso can be expected to carry on weakening against the dollar indefinitely.

A hundred years during which the peso has lopped off thirteen (13) zeros owing to chronic inflation shows that Argentina is politically and culturally incapable of responsibly managing its own currency.

Argentines know this. Unfortunately, only the richer ones have assets they can move to safety outside the country. The hand-to-mouth poor will continue being ravaged by inflation, not to mention the large quantities of counterfeit pesos in circulation.

Letting Argentines play with fiat currency is like handing out loaded pistols to rowdy 5-year-olds. In both these sad cases, adult supervision is urgently needed.

The grand history of Latin America: borrow billions of $$$ from U.S. banks, hand the money to the wealthy who immediately deposit it right back in American banks, and let the poor pay back the principal and interest. Hmmm…. seems more and more the way this country is going.

The fixed exchange rate under Kirchner was totally unsustainable. One difference between Macri’s neoliberalism and his predecessors is Macri is allowing much more of a floating currency than in the pre 2001 time period(We can debate how much it is actually is floating and clearly a lot of this debt issuance is for currency stablization that I personally don’t approve of).

And who are the adults? Let me guess, bankers and bondholders?

I’m not an expert in this at all, but in Peru, you could hold bank accounts in either national currency or dollars. The national currency accounts spared you currency exchange fees and also had higher interest rates. Most people who could hedged their bets by putting money in both accounts.

It seems like a happy medium between abandoning national currencies and letting savers get ravaged? No?

While not as spectacular of a return as Bitcoin, but impressive nonetheless, the escape route for an Argentinean @ the turn of the century was the golden rule, an ounce of all that glitters was 300 pesos then and now around 25,000 pesos, a most excellent ‘troy’ horse.

That is what I assume most who hold the barbarous relic are hedging against. It works in the US too, from time to time.

Values currently are illusionary everywhere, and so far-so good.

So, is austerity good or is austerity bad? And in what conditions?

I’m for expansionary government expense (and direct government ownership of some industries, such as with an NHS) balanced by taxes on high incomes.

So in my view the problem happens when the government lowers taxes on the rich, as seems likely in this case.

On the other hand taxes on the rich are likely to cause capital flight.

So why did Macri get elected to do this? Yeah he didn’t win by much, but he won.

>The hand-to-mouth poor will continue being ravaged by inflation

Which is freaking weird. Argentina has cropland. They have energy sources (and I won’t bore everybody…ok, I will… with the observation that the Industrial Age is generously a 300/8000 year ratio part of human history).

And doesn’t the below need some unpacking?:

>only the richer ones have assets they can move to safety outside the country

What are these assets? Why are said assets mobile? How did they come to “own” them? What percentage of the population is encompassed by “the richer ones” phrasing?

Question: why doesn’t MMT thinking work for countries like Argentina?

As wikipedia notes:

Is this a general flaw in MMT? Does MMT only apply to dominant nation-states like the U.S., who can use foreign military and financial pressures to protect the currency, aka the petrodollar? Is the petrodollar a true ‘fiat currency’ or is it somehow based on control of commodities (especially oil)? Is there something peculiar about Argentina and other countries facing currency devaluation that MMT doesn’t handle well? Any ideas on this?

That wikipedia write up isn’t wrong, but it could be better. Probably need to hammer home the point that the sovereign can always pay IN THE CURRENCY THAT IT ISSUES.

Most of the MMT related conversations on this site, and the posts that are written up on the subject are mostly about explaining how there are constraints that many people THINK exist in the USA, but don’t actually exist, at least in economic terms (political constraints notwithstanding). A country cannot be forced to default on a currency it issues. If the USA had significant debts in EUR or JPY, then it’d be a very different conversation.

External constraints are a big deal for most countries, especially developing countries that depend on exports of primary commodities. Chile, for instance, is constrained by balance of payments problems when the price of copper declines. Also, developed countries that are relatively smaller have much more limited sovereignty. The Swiss Central Bank has to follow what the ECB does, to a large degree.

On the other hand, there’s episodes where some countries have found room for maneuver when they give up their sovereign currency. I didn’t expect that Ecuador’s economy would perform quite as well as it has in recent years. But, they’ve shown that you can find ways to get creative to compensate for loss of monetary sovereignty. Of course, the fiscal constraints are real since Ecuador can’t print USD.

Brazil’s recent neoliberal turn was frustrating for a variety of reasons, but being a big, diverse economy, they’ve got more sovereignty than their neighbors. However, the business and political elites in Brazil decided to hammer through austerity (spending cuts and interest rate hikes) because they WANTED to, not because external forces made them do it.

No doubt an MMT prescription for Argentina would advice them to lay off the $ denominated debt and stick to pesos as much as possible. I’d imagine Stephanie Kelton or any of the UMKC crew would advise curtailing imports or doing some import substitution in order to take pressure off balance of payments issues. They’d also take a look at what was driving inflation domestically and try to find ways to relieve it with a targeted approach, instead of risking recession and unemployment. Neoliberal/Washington Consensus type economists would say hike interest rates, cut government spending in order to curtail demand. They’d argue that the private sector will make the best decisions about where to reign in spending to reduce inflation.

A hundred billion in new debt in about two years? I sure hope the transaction fees for that much debt did not flow back to those authorizing such an obscene amount. Next thing you know, they’ll want to rebuild their water treatment facilities for a few tens of millions, and the voters will find they’ve been saddled with another billion in debt.

Debt is often deemed a good because of the political and economic leverage it gives to the creditor(s), an observation that doesn’t require being a fan of the current Bond series. Alexander Hamilton would agree, as would Paul Ryan, who is about to tell us that the US can’t afford Medicare because of the taxes no longer coming in from corporations and the super wealthy. The obvious answer to that will probably pass Ryan by, as it would his peers in Argentina.

I have been to Argentina a few times and I have two key take aways:

1) There is no investment in Argentina; no cranes, no building , nothing. Lot’s of investment opportunities but nobody is making them for many years!

2) I am always amazed at how energetic and tech savvy the young people are.;

Problem seems to be lack of investment probably because of too much government corruption, incredibly high import taxes and excessive patronage system.

Kirschner was incredibly corrupt and buried the country. Give Macri a chance. They need to borrow more and make good investments.