By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently working on a book about textile artisans.

During last week’s Commonwealth summit in London, UK prime minister Theresa May called for a new alliance to combat plastic pollution, as part of which “she was prepared to ban plastic straws and coffee stirrers” according to a Saturday piece in the FT. In December, her government had committed to eliminating all avoidable plastic waste by 2042, as well as implementing new measures such as a bottle deposit scheme.

Seriously? This is intended as a serious assault on plastics, but appears to me to be as well thought through and sufficient to confront the magnitude of the problem as her government’s Brexit plans.

Some were willing to describe the plan as “bold”. From the FT:

“Definitely the UK is taking a very bold approach to plastics right now. It is very visible,” said Kim Christiansen, regional director for PlasticsEurope, an association of plastics producers. “It is a high-profile issue here in the UK, and higher than I think you would find in other European countries.”

Not me. But then, I don’t draw a paycheck from an association of plastics producers.

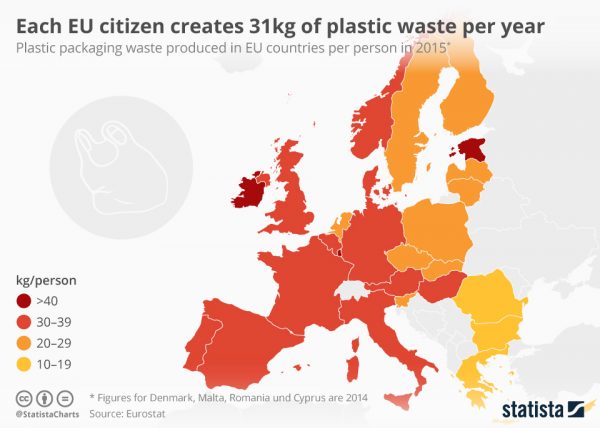

The UK’s plan is as manifestly inadequate as the EU’s first-ever European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy, announced on January 16 (which I discussed further here). The average EU citizen generates 31 kg of plastics waste each year, according to statista. The figures vary widely among EU members: Ireland is the highest, 61 kg per person on average, and Bulgaria, the lowest, at 14 kg; the UK is a smidge more than 10% higher than the average, at 35 kg.

Source: statista.

May’s approach is mere window-dressing, as two sources cited by the FT make clear:

“Cotton buds, plastic straws, things like that — they are low-hanging fruit,” said Ferran Rosa, waste policy officer at Zero Waste Europe, a non-profit based in Amsterdam. “We need a systemic approach, and that would be much more challenging for the government.”

Chris Cheeseman, a professor of materials resources engineering at Imperial College, said: “It is missing the point, and it’s not going to do anything to reduce plastics in the ocean, which must be the ultimate aim.

“Banning plastic straws or plastic stirrers is just nonsense really, against the huge problem with waste management in developing countries,” he added.

The UK recycles only about a third of the plastics waste it generates, due to limited recycling capacity, and exports the rest to developing countries. The current UK plastics recycling system creates incentives to export plastics waste. (Jerri-Lynn here: Will Larry Summers please pick up the white courtesy ‘phone).

The BBC Blue Planet II series highlighted the problem of marine plastics pollution. Any long-term solution to the problem requires dealing with the waste before it gets to the sea. Over again to the FT:

“You can solve the problem in the oceans by solving the plastic problem on land,” said Adrian Griffiths, chief executive of Recycling Technologies, a Swindon-based manufacturer of plastic recycling systems. “If you make plastic valuable on land, it will stop people from throwing it into the oceans.”

Reining in Great Pacific Garbage Patch

But what about the plastics that are already in the oceans? This question brings us to the second plastics news that caught my eye today, as reported in today’s Independent:

Scientists are preparing to launch the world’s first machine to clean up the planet’s largest mass of ocean plastic.

The system, originally dreamed up by a teenager, will be shipped out this summer to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, [GPGP] between Hawaii and California, and which contains an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic.

The experts believe the machine should be able to collect half of the detritus in the patch – about 40,000 metric tons – within five years.

Last month, I wrote about a study that found that the GPGP– twice the size of France– which is growing at a rate faster than previously believed (see that post here). Most of the material in the GPGP is bulky, and comprises abandoned fishing gear. From my earlier post:

ABC reports that the NGO Ocean Cleanup will launch a program to clean up ocean waste within the next twelve months– two years ahead of schedule– using technologies it has developed. Ocean waste will be encircled by a barrier, which will then be transported back to land to be recycled. The NGO claims that full deployment of its systems would clean up 50% the GPGP in five years (Further discussion of this initiative is beyond the scope of this post.)

The initiative is admirable. It is an unusual– to say the least– to see a teenager identify a huge problem, design a solution, and implement it— well before his or her 30th birthday. Dutch engineering student Boyan Slat became concerned about plastics waste while diving in Greece when he was 16. Rather than despairing (according to the Independent):

“The plastic pollution problem has always been portrayed as something insolvable. The story has always been ‘OK, we can’t clean it up – the best we can do is not make it worse’. To me that’s a very uninspiring message,” said Mr Slat.

His response: creating The Ocean Cleanup when he was 18. This group will be launching the clean up device later this year (as reported by the Independent):

The clean-up contraption consists of 40ft pipes – ironically made of plastic – that will be fitted together to form a long, snaking tube.

Filled with air, they will float on the ocean’s surface in an arc, and have nylon screens hanging down below forming a giant floating dustpan to catch the plastic rubbish that gathers together when moved by the currents. The screens, however, will be unable to trap microplastics – tiny fragments.

That last sentence, about microplastics, leapt out at me. The system might well succeed in shrinking the GPGP, by bringing back some of the plastic waste to land where it can be recycled or otherwise managed. But it does nothing to address microplastics– which as I noted in my previous post, comprise only 8% of the GPGP, but have an outsize impact. These tiny pieces of plastic are ubiquitous, showing up fish, to bottled water, even sea salt. Their long-term impact on human life, not to mention other living creatures, is unknown.

Tackling microplastics looms as a major challenge. Yet at this point, collecting the larger components in the GPGP is one necessary step forward– a point Slat has emphasised (over to the Independent):

He told US business website Fast Company: “Most of the plastic is still large, which means that in the next few decades if we don’t get it out, the amount of microplastics can be tenfold or 100-fold. It’s this problem that’s waiting out there to magnify many times unless we can take it out.”

What Is To Be Done

On the issue of what is to be done, an editorial in yesterday’ FT called on governments and companies to clean up the worldwide plastics mess and featured three suggestions. The effort must be global, and the first necessary step is to reduce and where possible arrest outright the amount of plastics generated. May’s initiative is a step towards this goal, but a drop in the bucket compared to what’s needed.

Second is to create a circular economy, in which the aim is considers the entire life cycle of a product, and reduce waste throughout, replacing the prevailing take-make-consume-dispose model (as I discussed further here).

And a final step:

A priority for research is to improve recycling technology. A hint of what might be possible came last week when an international team announced the discovery of an enzyme that can break down PET, the polymer used to make bottles; it was extracted from bacteria evolving to eat waste plastic in Japan. The next big EU research programme could lead the way by adopting plastic-free oceans as a “grand challenge”.

‘The City of Seattle requires all food service businesses to find recyclable or compostable packaging and serviceware alternatives to all disposable food service items such as containers, cups, straws, utensils, and other products.

This applies to all food service businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, delis, coffee shops, food trucks, and institutional cafeterias.

In addition, businesses with customer disposal stations where customers discard single-use packaging must provide options to collect recyclable and compostable packaging in clearly labeled bins and these businesses must sign up for composting and recycling service offered by a collection service provider.’

From the Seattle Public Utilities website. Full enforcement will begin this July.

And, there is the whole plastic shopping bag thing. Bans on these seem to be almost impossible to impose on a state-wide basis. Maybe plastic bag manufacturers have a more powerful lobby than the plastic straw makers?

About 15 years ago, we arrived in Haute Savoie, France, to live for a couple of months while my spouse was working there. I loaded up at the local supermarket, only to find at checkout that the Department had just imposed a ban on plastic bags. I loaded the entire basketful of groceries, one by one, into the car, then unloaded, one by one, into our flat. I never forgot the reusable shopping bags after that.

There is increasing concern about microplastics entering the food chain. Some may just be passed through the digestive process, but some may interfere with human nutrient uptake. Another worry is toxic substances which adhere to the microplastic particles. The risk to human health is currently unknown.

What worries me is that the Fukushima disaster is still pouring radioactive particles into the Pacific Ocean. The increase in overall radioactivity in the ocean is tiny at present. But can these radioactive particles adhere to microplastics and perhaps concentrate further up the food chain?

That’s what terrifies me about chemicals and other manmade substances in general. Once that stuff is out there, it’s impossible to undo. Just as an example, think about all the stuff from a car that ends up all over the road from friction and leaks. And then it rains. Every road in America ought to be a Superfund site.

Even if we mitigated climate disruption, would we survive this? The former is an easy problem by comparison, I think.

I’m at a loss in general with all the detritus created by consumer capitalism. Growing up, in middle school, I was a acutely aware that all this stuff had to go somewhere, it can’t just disappear. This was back in the 90s during the reduce, reuse, recycle campaign. So little has changed. I guess most people really do think it just disappears after it’s throw away? (Selective ‘object permanence’?)

Imagine feeling the same way starting in the 70’s. Ugh. But then we thought we were going to do something about it. That softened it a bit then but makes it much, much worse now that we’ve failed.

In a way it did disappear. That was because it was being shipped to China! But now the Chinese have said no more so I think that people will be seeing more and more of the stuff that they throw away. This is a process know as going cold turkey.

First of all to note that while its good campaigning to link plastics recycling to plastic waste in the sea in Europe, they aren’t really linked – the majority of plastic waste in the Atlantic arises from fishing boats and cargo ships dumping waste to save on harbour servicing costs. In the Pacific, the great majority of waste comes from the poorer Asian nations where there are no proper collection facilities, so it invariably ends up in rivers, and then to the sea.

But back to Europe – the blame here lies on our old friend neoliberalism, and more specifically on the EU and its competition directives. Things were bad in the 1980’s and 1990’s, but there were real moves then to integrate collection and recycling policies at a local level, combined with the closure of landfills and older incinerators in order to create a solid market for recycled waste. All that was destroyed by EU Directives (aided and abetted by many national governments and the usual lobbying suspects) which decreed that waste collection should be subject to ‘competition’. This lead to the breakdown of integrated policies. Allied to this was the resurgence of incineration as a waste treatment option – incinerators need a high plastics content to maintain burn temperatures, so there was an immediate competition for recycling. With such a fragmented and uncertain future, the industry lost interest in investing in plastics recycling. The drop in the price of the precursors for PE plastic resulting from the fracking boom was the last (plastic) straw.

I don’t believe that trying to promote plastics recycling will do very much, the market is too uncertain for producers when they can buy the raw virgin materials so cheaply. It has to be from the supply side – this means much stricter regulations on the types of plastics used, banning the mix of plastics in containers (this makes recycling very difficult) and focusing on re-use, etc. But most of all, we have to move away from excess use, and only regulatory or tax policy can do this.

Do you have any insight into why the Irish figure is so high?

I haven’t a clue– but included it b/c it was such an outlier, and thought a reader might know. I’m curious.

It might not be such an outlier. For example, if the northern Irish figure was 39.0 and the Republic figure was 40.1, then we’d see the map we see. Has anyone got at the raw numbers? statista covered their web page up.

I was actually very surprised to see that, I wasn’t aware it was so high. A lot depends on how they calculate those figures – for example, are they including transport packaging? Most Irish fruit and veg has to come from the European mainland by sea so its possible this just reflects more secure packaging needed for longer supply chains. The Irish also tend to eat more processed food than most Europeans (except for Britain, they eat the most), so this may be reflected in more packaging. I also wonder if they’ve thrown in agricultural plastics into the figures, the agriculture industry is huge in Ireland and is a major user.

I also, as a personal rule of thumb, subtract 10% from any ‘official per person’ figure for Ireland, as I suspect the Irish population is that much larger than is in the census figures – mostly due to east European casual workers not bothering to go through official registration.

I’d be sceptical that its significantly higher than the UK, as the supermarket chains overlap, so there would be no specific reason for more – and certainly far fewer plastic bags are used in Ireland than in the UK due to a long established plastic bag tax here.

So my guess is that if you looked at those figures more closely there would be some confounding factor in how they are calculated.

I looked at an article in The Journal yesterday, these figures are from memory. The figure for the south is 61kg, and the next lowest is IIRC 52kg. The official figure for the UK is something like half the official figure for the Republic, which is baffling. I would have thought that, as you say, household usage would be slightly lower here. I would expect that as a result of the composition of Irish industry (meat packing, pharmaceuticals, microprocessors), we would use more than our share of plastics, but I’m surprised that it’s so much higher than, say, Denmark, which I understand also has a large beef industry.

Bug that eats PET

I used to have a yen for writing a script for one of those sci-fi disaster movies about a plastic eating microbe that eats plastic and consumes our current lifestyle. Well folks, according to a BBC inside Science radio programme, the situation (in watered down form) is already with us due to bacteria found in a Japanese dump.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b036f7w2/episodes/downloads

Pip Pip

Of course, we have move away from excess use. Life without plastic is possible, especially those plastic things that are supposed to make our daily lives easier.

I have lived through the plastic ‘revolution.’ I can remember life without plastic; no plastic garbage bags, no single-use zip-lock baggies (NOT recyclable, BTW), no plastic shopping bags or plastic produce bags, or styrofoam meat trays, or plastic wrap for leftovers, or plastic milk and juice jugs. Humans can survive without these.

Yes, I look back into my childhood when there were no plastic “things” and try to remember how we carried things, stored things and recycled things. We used paper bags, we used waxed paper for meat and perishables and we burned our garbage. I do not know how we are going to get rid of that clear film that seems to be wrapped around many foods. We have been using our own grocery bags for about 20 years now and refuse to use those one-time only plastic bags. Now I get my fruits and vegetables and put them naked into my reusable bag.

I used to pick up roadside trash but now that I am nearing 80 years old, it is not so easy. So I phone the school, for instance, and suggest that the students pick up the garbage around the school yard and in their own ditches. When plastic garbage is thrown into the ditches alongside the roads, it is flushed from the ditch into a creek and from the creek into a river and from the river into the nearest lake and/or ocean. Why can’t everyone visualize that?

There is a small company in a nearby province that is trying to build a plant to recycle plastic into fence posts and outside furniture. I hope they succeed.

And people continue to shop online, with free or not-free delivery.

Take the following example. Instead of driving to a store to pick up a shirt, the post office deliver to you. So, maybe there is a wash there, as far as gas usage goes.

But you might be in the mall to buy more than just one item. That would be many trips by the postman, but just one trip for you. So, maybe online shopping is less green.

You can decline to put your merchandise in a bag. But the online retailer will wrap your purchase in a paper box (cardboard or corrugated), protected it with some cushioning material (more kraft paper or plastic bubblewrap, etc) – a lot of it if breakable -, and seal it with a shipping label (glue and paper usage here), and tape it with water-activated paper tape or pressure sensitive plastic tape.

And in today’s link, Amazon is getting closer to No. 1 in apparel.

We are looking at more waste – paper, gas, etc.

Yes!

I have Amazon Prime (thinking about getting rid of it). In order to meet the 2 day shipping deadline Amazon has started delivering my orders via UPS. Wasteful. The Post Office drives down my road six days a week but UPS has to make a special trip. That’s why I am thinking about dumping Amazon Prime.

Not long ago the EU passed legislation supposedly to protect consumers on olive oil packaging to avoid fraudulent (myth? fact?) restaurants mixing olive oil with sunflower oil. Now olive oil has to be packaged like ketchup in certified processing plants. More waste!

Do people cold-press their own olive oil at home?

Not! but restaurants could buy 1L bottles or 5-25L cans (totally recyclable) and now they have to buy thousands of small plastic minibags or 150 ml plastic non-refillable bottles.

In Spain 5L olive-oil cans are very popular.

Atax of one euro cent per kilogram of plastic waste, could make miracles!

“The average EU” (or US?) “citizen generates 31 kg of plastics waste” is a lie. Plastic manufacturers generate the waste. This is just a way to shift the blame. The average EU CONSUMER may purchase goods containing, or contained by that much plastic, but they certainly don’t *generate* it. The system making money off the consumer is what generates it. If they didn’t make it; and sell it; problem solved.

That type of blame-shifting has been prevalent in our culture for so long that many accept it as fact…when it is JUST A HUGE, BIG, FAT. LIE!!!! Perpetrated by government agencies and lobbyists to protect certain business interests.

I agree.

It’s very difficult to avoid the majority of the useless plastic that’s foisted on us with everything we buy.

Thanks for this, Jerri-Lynn!

A tiny corrigendum, since it’s a mistake I see all the time: “Reigning in Great Pacific Garbage Patch” has one ‘g’ too many. A useful mnemonic: “One who reigns holds the reins of state.”

[And I tried very hard here to avoid falling prey to Muphry’s law, but no guarantees.]

Thanks– I know that, and would have sworn that’s what I typed. I didn’t use your mnemonic, but said to myself as I was composing this, rein– as in rein in a horse– which has no g. But I obviously typed otherwise– now fixed. Thanks for reading my work so carefully and drawing the error to my attention.

My fingers do that, too. They have a mind of their own. It’s very frustrating.

People in the US feel self righteous about recycling because they think we (the US) are recycling. We are mostly not. Most of the waste is shipped to China and third world countries, hopefully to be recycled. I suspect if one those recycling destinations gets overwhelmed by the volume they just dump it into the nearest river or ocean.

Then there is the cost of this faux recycling. My township has six dumpsters they fill up every other Saturday. I’m sure they pay for this privilege. This gets trucked north 60 miles to the recycling center probably to be sorted, compacted and shipped 250 miles south to a port on the Great Lakes. Then it’s hauled to some other country that may or may not actually recycle it. The way “we” are recycling is probably more expensive than subsidizing someone to do the work here. We have pushed the “Easy” button but ultimately it is not easy or perhaps cheaper.

MAYbe the reason the conservatives don’t have a good plastic waste policy is because they are anti science? Just look at their stance towards their universities

I think glibly dismissing the very visible, if largely superficial, campaigns to ban or stigmatize the use of plastic straws and shopping bags ignores the important role of these campaigns in raising ordinary consumers’ awareness of the problem. If the bulk of the problem is really fishing gear, then the most effective method for reducing the problem would seem to be focusing on a single industry, fishing. To the extent that the problem is also due to a corporate ‘culture’ of overpackaging, raising consumer awareness through superficial gestures seems like a useful precursor to building the political will to take on entrenched corporate interests.

In addition, though the cleanup invention does not directly collect micro plastics, removing larger pieces will reduce the source of microplastic waste created by collisions and weathering of larger pieces.