After so many cases arguing that gig economy workers should be deemed employees rather than independent contractors have failed, yesterday’s decision by the California Supreme Court, in Dynamex Operations W. v. Super, was a welcome and seemingly overdue restoration of common sense. This ruling implements the same rules that Massachusetts has adopted. That means not only is it significant by mere virtue of the size of the California economy, but it may be embraced by other states wrestling with this issue.

An overview from the New York Times:

The decision could eventually require companies like Uber, many of which are based in California, to follow minimum-wage and overtime laws and to pay workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance and payroll taxes, potentially upending their business models.

Industry executives have estimated that classifying drivers and other gig workers as employees tends to cost 20 to 30 percent more than classifying them as contractors. It also brings benefits that can offset these costs, though, like the ability to control schedules and the manner of work.

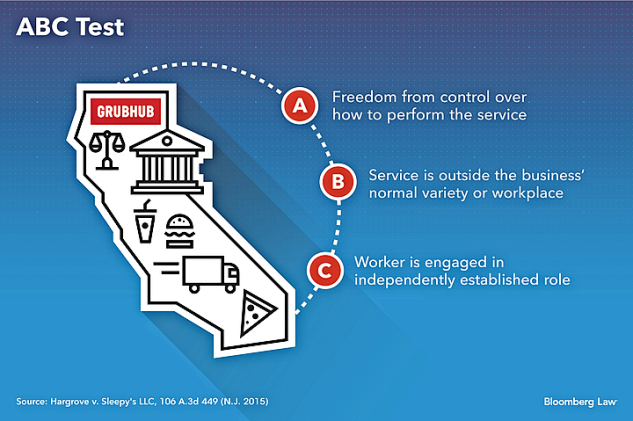

As we described very briefly yesterday, the ruling puts the burden of proof on companies to show that their relationship with a worker satisfies all of the three prongs of this “ABC” test for them to be deemed to be an independent contractor. Bloomberg Law provides this chart and summary:

The three factors are whether (A) the worker has freedom from control over how to perform the service, (B) the service is outside the business’s normal variety or workplace, and (C) the worker is engaged in an independently established role.

And from the Times:

By way of an example, the court said a plumber hired by a store to fix a bathroom leak would not reasonably be considered an employee of that store. But seamstresses sewing at home using materials provided by a clothing manufacturer would probably be considered employees.

In addition, a company must show that it does not control and direct the worker, and that the worker is truly an independent business operator, not just classified that way unilaterally.

Since employment law is not one of our regular beats, let us turn over the mike to reader anon, who provided more detail in comments. I had raised the issue as to whether this decision could also help workers hired through temp agencies who in fact wind up tasked to what sure looks like a regular job but without the benefits, stability, and dignity. His take:

I am not a lawyer and wouldn’t even call myself an expert, but I have some knowledge in this area.

The court’s decision is great for workers, but unfortunately, it is unlikely to affect the temp employee scam you refer to except that it may permit a more expansive concept of joint employment (where a temp employee would be considered jointly employed by the temp agency and the user employer). The decision is most relevant to the scenario where companies try to misclassify employees as (1099) independent contractors — think Uber drivers. In the temp agency scenario, the worker is usually considered a (W-2) employee of the temp agency, and the temp agency is a contractor to the user employer.

The court adopted Massachusetts’ version of the ABC test for differentiating employees from independent contractors. The ABC test, and the Massachusetts version specifically, is the strictest/most pro-worker test for this purpose. The test requires that a worker, in order to be considered an independent contractor, must meet all of the following requirements (this is a summary, not an exact quote):

(A) free from control in the performance of the services

This factor is part of most tests for differentiating employees from contractors, including California’s old Borello standard and the IRS’s common-law employee test. The problem is that it can be a really gray area with operations like Uber and leads to a lot of argument in litigation; my view is that Uber and similar operations fail this prong, but Uber’s lawyers use flexible scheduling, the lack of human supervision, the employee’s ownership and choice of vehicle, and other factors like that to argue otherwise.

(B) the work must be performed outside the employer’s usual course of business

This is also a part of most other tests (often phrased as “is the work integral to the employer’s business”). It basically means “is the employer in the business of performing the same type of work?” For example, driving is performed in the usual course of business for a taxi service like Uber, so Uber easily and unambiguously fails this prong. (Uber tries to argue, unsuccessfully so far, that they are a technology company producing an app that connects people looking for rides to oh-so-independent drivers.)

(C) the worker must be engaged in an independently established trade or business

This just means “did the worker independently establish this business, or did their ‘business’ consist of filling out a job application on the company’s website and suddenly becoming an ‘independent businessperson’.” Besides the date of creation of the “business,” the court will look to other factors to determine whether an independent business really exists: Do they advertise their services? Do they have a website describing their business? Do they have multiple clients, or have they attempted to obtain other clients? Have they made some kind of genuine capital investment in the business (a personal car is unlikely to be persuasive)? Do they have employees or have they shown an intent to hire employees? “Gig economy” workers fail all of these. These are not hardline factors; for example, a worker who drives for both Uber and Lyft is more likely to be seen as analogous to an employee who works part-time for both Walmart and Target, than an independent businessperson with multiple clients.

This is a nightmare for the “gig economy” because, while they can argue all day about control, they unambiguously fail prongs B and C — and they must pass all prongs in order to classify a worker as a contractor. Also, the unfavorable Grubhub ruling from a few months back, now on appeal to the 9th Circuit, will definitely be overturned based on this new standard.

We’ve embedded the decision below. Wired discusses what this decision might mean for gig economy companies in more detail:

The big question is whether gig economy companies can stay afloat if they hire all their workers as full-fledged employees. Payroll taxes and other expenses associated with converting contractors to employees could increase an employer’s costs by about 25 to 40 percent per worker says Andrei Hagiu, a visiting associate professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Gig economy companies already face difficult economics. Uber lost $1.1 billion in the fourth quarter of 2017, according to the Wall Street Journal. Some companies that tried to convert workers from contractors to employees have already folded or changed their business models, including on-demand shipping company Shyp, food-delivery company Sprig, and caregiving company HomeHero. “They’re operating on very thin margins,” Hagiu says. “I don’t think they can afford it.”….

Stanford business school professor Jeffrey Pfeffer argues that the model of many gig economy companies was not sustainable. “When those without workers’ compensation get injured, society pays,” he tells WIRED. “This is cost transfer from the wealthy (companies) to the (comparatively) poor workers. Holding aside any particular court decision, this was and is completely unsustainable in the long run.”

New York University Stern School of Business professor Arun Sundararajan says the gig economy will survive, but prices will be higher, at least in California, and push companies to adopt more automation. “It doesn’t threaten the long-term viability of businesses as a whole, but I think it will shrink their market in the short term because it will decrease sales,” Sundararajan says.

We will confess to having our priors on Uber, but it is hard to take Sundararajan as being up to speed on Uber in light of what he’s quoted as saying next:

Sundararajan says newer, smaller companies will have a much harder time than well-funded companies like Uber and Lyft, which will be better able to absorb costs and have established large labor forces.

Now it may be true that Uber can hang on longer than some younger companies regardless, but the idea that Uber is “well funded” is a widespread misperception. At its current burn rate, Uber is out of money in a bit over two years, and panic and abandonment of the ship will likely set in sooner than that. Our Hubert Horan deems an IPO to be a pipe dream, given SEC disclosure requirements (Uber has gone to extraordinary lengths to make it impossible for investor to track financial results over time) as well as the lack of any prospect that the company can be profitable, save at a very small fraction of its current size.

In addition, Uber does not have a “large, well-established labor force”. Driver churn is high and getting worse. One account claimed only 4% lasted for more than a year. Uber’s own admissions to the press aren’t much better. They say 30% churns every quarter. Pull out your calculator. That means only 24% are left after a year.

And the plural of anecdote is not data, but this is from an Uber driver as of the beginning of April who was working with about 45 other drivers via Twitter to get more accurate information:

Since XChange leasing ended Uber doubled the sign up bonus. Otherwise no specific intel in my area. On the forum it seems new drivers are actually burning out even faster than in the past, like the whole process is accelerating, instead of 6-8 weeks, more like 3-4 weeks to burnout.

So if anything, Uber’s driver turnover is getting worse.

Shorter: this couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch.

Dynamex CA Supreme Court

Big “blog”, or big “blow”?

I saw that just now…my tendency to typos plus trying to get this up before Links launched.

My fingers get fatter year by year – even though I learned to touch type in middle school (an excellent idea on my mother’s part – she’d seen my handwriting).

You can try to edit, but you won’t get all of them.

Will this affect Fedex drivers? They’ve been long misclassified as contractors in order to evade unions.

I’m pretty sure fedex drivers and material handlers are employees. There may be exceptions for peak period fill-ins, but check this out: https://careers.fedex.com/express/jobs?stretch=10&stretchUnit=MILES&location=Seattle%2C+WA&woe=7&page=1

Now fedex does also use contractors with their own vehicles for some deliveries – mostly seasonal and/or rural – so this may be what you are talking about.

My nephew works for Fed-Ex (in loading) and said all the drivers in his center are independent contractors. When I drove for UPS a long time ago (for 2 1/2 yrs) UPS drivers were constantly trying to switch to Fed-Ex since it was a much better job. Fun fact about UPS, my supervisor used to regularly physically change my time card to say that I took an hour lunch even though I routinely went out with 10 hour planned days and had no chance to ever stop for lunch.

Nope. Not just seasonal and rural. Everywhere.

Look at the logo on the truck. When Fedex is in orange letters, they are employees.

The “independents” who buy their route, buy their own truck, insurance, uniforms and pay all costs, are the ones with the green “ex” in Fedex. Confused? Think green for greed and cash.

They are the ones that drive really fast and throw packages at your doorway because they are paid per package delivered.

http://money.cnn.com/2014/11/20/news/companies/fedex-driver-lawsuit/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertwood/2015/06/16/fedex-settles-driver-mislabeling-case-for-228-million/

The crumbling of the ‘gig economy’ is delicious. I think that in the future, people will look at the period of 2000 to 200? at the wild west of capitalism. Hopefully things will get better for citizens in the future and not worse.

FedEx Ground drivers are (mis)classified as contractors, that’s the core of their competitive advantage over UPS.

Yep. A local “contractor” parks his FedEx truck at the golf course in the late afternoons and on weekends. No one seems to realize what that means…

FedEx Ground drivers are contractors (or technically, FedEx says employees of a contractor company). FedEx Express, and presumably other service, drivers are direct employees.

Somehow their prices are around the same (sometimes more, sometimes less) than UPS (who has unionized Teamsters labor) despite the competitive advantage of misclassification. Even if their price ends up lower I’ll never use them due to their labor mistreatment; I’ll use USPS or UPS. FedEx also viciously opposed the Employee Free Choice Act in 2009.

Amazon does this too.

In most/all? big metro areas, white van contract drivers deliver most packages. Amazon also uses an Uber style app to have ‘gig contractors’ deliver packages in their personal vehicles.

Fox, DHL

The Fedex question is a good one.

I’m the anon commenter quoted in Yves’s post.

There has been a lot of litigation over the years over the classification of FedEx Ground drivers, with mixed results. At the federal level, the NLRB has continually found their drivers to be misclassified employees (and thus subject to the NLRA), but FedEx, represented by Ted Cruz, appealed the NLRB’s initial order around 2009 lucked out with a favorable DC Circuit panel (two GOP appointees plus Merrick Garland, who you may recall as Obama’s SCOTUS nominee the GOP refused to hold hearings on or consider). The GOP appointees unsurprisingly refused to uphold the NLRB order, and Garland dissented. The NLRB issued another ruling sometime around 2014 (IIRC); the DC Circuit refused to uphold it due to the previous judicial decision on the same issue. The NLRB tried for en banc review, but that was denied.

Notably, one of the cases against FedEx, Schwann v. FedEx, involved Massachusetts drivers. (Recall that the California Supreme Court adopted Massachusetts’ version of the ABC test.) The district court initially ruled that the drivers were misclassified, quickly finding that FedEx utterly failed prong B (FedEx is in the business of delivering packages, so the work of their delivery drivers is logically in the usual course of business for them; never mind that FedEx tried to argue they weren’t a delivery company, but actually a “sophisticated information and distribution network,” just like Uber’s arguments of being a technology company rather than a taxi company). FedEx appealed and prong B ended up being severed from the test on federal preemption grounds specific to transportation carriers like FedEx, but the workers still had the opportunity to make their case on prongs A and C. It looks like FedEx ended up settling, which I suspect means the workers were likely to win.

My understanding is that FedEx no longer 1099 contracts with individual drivers and instead only contracts with incorporated entities who hire employees to do multiple routes. Since the delivery work is ultimately being done by properly-classified employees, this decision shouldn’t have any effect on FedEx’s current model. It’s possible the decision could be used to establish joint employment by FedEx of these drivers, but I haven’t seen any legal commentary on that, and it would only help to hold FedEx jointly liable if there were violations of state employment laws like wage and hour. It will not help them unionize, because the state law standard does not affect whether the drivers are considered employees under the NLRA, which uses the federal common law standard. (And as mentioned above, the NLRB is effectively foreclosed by the DC Circuit rulings from making an enforceable finding that FedEx employs or jointly employs these drivers, unless either Congress changes the law or FedEx makes sufficient changes to their driver relationships to render the prior DC Circuit rulings obsolete. Not that Trump’s NLRB would ever think about doing anything that is in any way, shape, or form positive for employees.)

Nice to have some good news in the daily feed. I’m glad to see that courts are starting to bring some sanity to the realities of the gig economy.

Good news, yes. But no way is the las word. Does anyone here think that SCOTU would agree with California?

The “gig” employment modle is not just worth billions, tts a part of the neoliberal/libitarian fantisy of free market pimicy. A “gig worker” is a free human being, while an employee is just another corpreate slave.

This is a California Supreme Court decision interpreting California law. There is no federal question and no route for an appeal to federal court, save for some very specific and rare scenarios involving industry-specific regulation and federal preemption (as in Schwann v. FedEx).

What about those who work in Amazon’s warehouses? I thought that I read that they are not employed directly by Amazon but by an outside agency who sends them all to Amazon.

I guess that this decision will mean, as Yves points out, that other state’s courts will now have a major precedent on the law books to refer to. My own, prejudiced, opinion is that the gig economy should be killed by fire so this is a great ruling

There should be no impact to Amazon or similar operations as long as the outside agency’s workers are properly classified as employees. The outside agency is a contractor to Amazon; the individual workers are employees of the outside agency (and under a sensible law, would be considered jointly employed by Amazon, but that is not always the case).

At most, this decision might make it easier for Amazon to be considered a joint employer under California wage and hour laws, which would allow Amazon to be held jointly responsible for paying damages relating to issues like unpaid wages. However, I would bet that Amazon requires their temp agencies to force arbitration agreements with class-action waivers on the workers. If the workers tried to sue Amazon to avoid the arbitration agreement, Amazon would likely be able to compel arbitration based on the temp agency’s contract. Arbitrators are corrupt and almost completely free to ignore the law as much as they want; the standard for having an arbitration decision rejected in court is super, super high under the FAA.

Obama’s NLRB expanded joint employment under the NLRA, in Browning-Ferris, which has the effect of allowing workers to collectively bargain with their real employers and not just a temp agency. One of the GOP NLRB’s first major moves was to overrule that decision, but a few months later they were forced to rescind that due to conflict of interest issues with GOP NLRB member William Emanuel, who is from Littler, a large employer-side law firm. Littler represented a party in Browning-Ferris. There is an obvious conflict of interest with a Littler lawyer making a major decision like this that would help a Littler client. The Obama-era standard is technically law right now, but since the NLRB General Counsel is also a GOP appointee, he can (and probably will) just refuse to prosecute cases based on the expanded standard. And the Board will be looking for another way to overrule Browning-Ferris in a different case and a more legally defensible manner.

In labor policy, the worst Democrat (even Obama or, probably, Hillary) is materially better (more pro-worker) than the best Republican. The parties are not the same.

Thanks so much for your very helpful additions. As indicated, this is an area of law I don’t follow, so having someone who knows the terrain weigh in is great for all of us.

Thanks for posting this. I’m preparing a presentation on labor rights for independent workers (title: Freelancing Isn’t Free), and this information will be very useful. Especially for countering arguments put out by proponents of the so-called sharing economy.

This should send chills down the board of Uber. No IPO for you!

Speaking of radical change, Richard Wolff on CounterSpin podcast: https://fair.org/home/richard-wolff-on-questioning-economic-fundamentals/

Does anyone know whether this could be taken to apply to actors and other film industry employees? I’ve heard the use of ‘independent contractors’ is pervasive there, and I note this was a California court which presumably has jurisdiction over Hollywood.

Peter Jackson was successful in getting New Zealand law changed just for the film industry by arguing that not doing so would violate industry standard practice and cause New Zealand companies to lose business on a large scale. In the film industry, ‘standard practice’ usually means ‘Hollywood.’ I remember wondering at the time whether that was really true, and the laws described in this article raise further questions.

One would think that unions like SAG-AFTRA and IATSE would be very interested in this ruling.

Okay but won’t the “employees” now just be made part time per-diem “employees” to avoid giving any benefits, job security, etc?

I’m not seeing how the ruling will reverse crapification of the jobs. Baby boomers w side income from SSi are so numerous, companies can just hire 2 p/t retired boomers on low salary rather than give f/t employment capable of paying even a low IBR student loan term to unemployed graduates?

happy May Day, and happy Dynamex Day!

As a misclassification nerd of five years, it’s hard not to do a little dance right now.

“Misclassification nerd” — I love it. I think I’ll adopt it myself, if you don’t mind!

Please do.

Here is my contribution to the literature. Out of date but still relevant in some ways. I wonder if Dynamex will be the final nail in the coffin of some of the also-rans such as Taskrabbit. That is, if the whole lot are not killed by fire, as the Rev Kev would say.

http://therealnews.com/t2/component/content/article/269-kevin-carhart/1764-the-ten-ninety-nihilists

I got a chance to interview the wonderful Cathy Ruckelshaus from NELP!

There’s also liability for corporations using Taskrabbit (and similar services) for long-term help like you described in the article. Also, joint employment between Taskrabbit and the user corporation? :D

Coincidentally, in the time between this little subthread and now, TRNN has rolled out a new website. Who knew. So the link I pasted in on the 3rd is no longer good, but here is a replacement in case anyone is down here and tries to use it.

https://therealnews.com/columns/the-ten-ninety-nihilists

(It appears that they went to the painstaking work of converting all of their old “columnists” into their new URL scheme rather than just toss something out that ran five years ago, so thank you TRNN.)

1) Uber Cab was NEVER going to have an IPO. Travis “High” Kalanick knew that almost from the beginning, I believe. Mr. Horan has unrebutabbly spelled out how there is no fricking way that Uber Cab could ever qualify under the SEC, etc. to do that.

2) I am surprised not to hear in discussions about Uber Cab misclassifying its driver employees as subcontrators that the latter would have major control over price. Heck, those poor saps don’t even know where a trip is going to go before they accept it (and have VERY harsh penalties for cancelling once they find out). It is common for Uber Cab drivers to accept a trip that involves an unpaid 20+ minute drive to the passenger’s location, and then only goes several blocks or so (with being paid based primarily or solely upon that latter distance). I drove a (legal) taxi for a year in 205-2016 during the most recent oil industry bust, and daily turned down trips that would have been financially catastrophic to take, or had too likely a chance of the pax not being there when I arrived (club or long distance away, mainly).

3) Next, I would hope to see any H1B, etc. visa type that doesn’t involve a salary of at least 100K net to the employee get cancelled as invalid. Either or both of the “at that low a salary, obviously an American could be found to do it” and “it’s intentionally undercutting American wages, which is officially illegal” would qualify.