By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Divergente Research LLC and Safehaven.com. Originally published at Safehaven

Worried about an economic slowdown amid worsening trade relations with the U.S. and a credit crisis sparked by a massive deleveraging drive, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), has unexpectedly made a massive 502 billion yuan ($74.36 billion) available to commercial banks in the form of one-year medium-term lending facility (MLF).

The money is meant to encourage more bank lending after a multi-year campaign by the Beijing government to curb debt started causing serious shockwaves in financial markets. A record numbers of companies ended up defaulting on their debt obligations in the current year.

Going Easy on Deleveraging Drive

The central bank is gradually adopting looser monetary policies to alleviate the effects of a huge deleveraging drive that include a worrying economic slowdown, with the economy projected to expand at 6.5 percent in the current year after growing 6.9 percent in 2017.

The latest move by the PBOC came as a surprise to many because no MLFs were due to mature on Monday. The bank typically injects fresh liquidity into the banks on the day existing loans mature.

Interestingly, the one-year MLF remained pegged at 3.30 percent, unchanged from the previous MLF injection—a clear sign that the central bank wants to encourage companies to borrow more. The $74B figure is the most by the bank since MLF was launched four years ago.

It’s now clear that the central bank is moving towards monetary easing from a more neutral stance.

The latest twist comes hot on the heels of reports that the bank had on Friday asked lenders to invest in more lower-grade corporate bonds in a bid to support the $15-trillion asset industry.

The PBOC has in recent months focused on adding liquidity in a targeted fashion in a bid to alleviate funding pressures especially in the private sector, where companies have traditionally faced considerable obstacles trying to obtain credit. The bank has so far cut reserve requirements for banks three times this year.

Chinese companies are going through one of their worst years in recent times, with the number of companies that have defaulted on bond repayments reaching record levels.

By the end of June, companies had failed to honor 33.3 billion yuan ($4.9 billion) in bond repayments, surpassing the previous record of 30 billion yuan set in 2016 for the entire year. But the biggest blow struck early this month when coal miner Wintime Energy defaulted on local bonds worth 72.2 billion yuan ($10.8 billion), a record for the country.

A severe credit crunch can certainly put the skids on the economy.

No Immediate Risk

The Beijing government has largely adopted a hands-off approach as far as managing the country’s fiscal policy is concerned. But China’s State Council, the supreme organ of state administration, has pledged to be more proactive in determining fiscal policy going forward. The government seems keen on reactivating its old engine of growth by accepting more leverage.

While that may impact credit risk due to the current high levels of indebtedness by the nation, Morgan Stanley says there’s no immediate risk due to the government’s financial and capital account controls.

Still, PBOC will do well to steer clear off any dubious tinkering with the yuan.

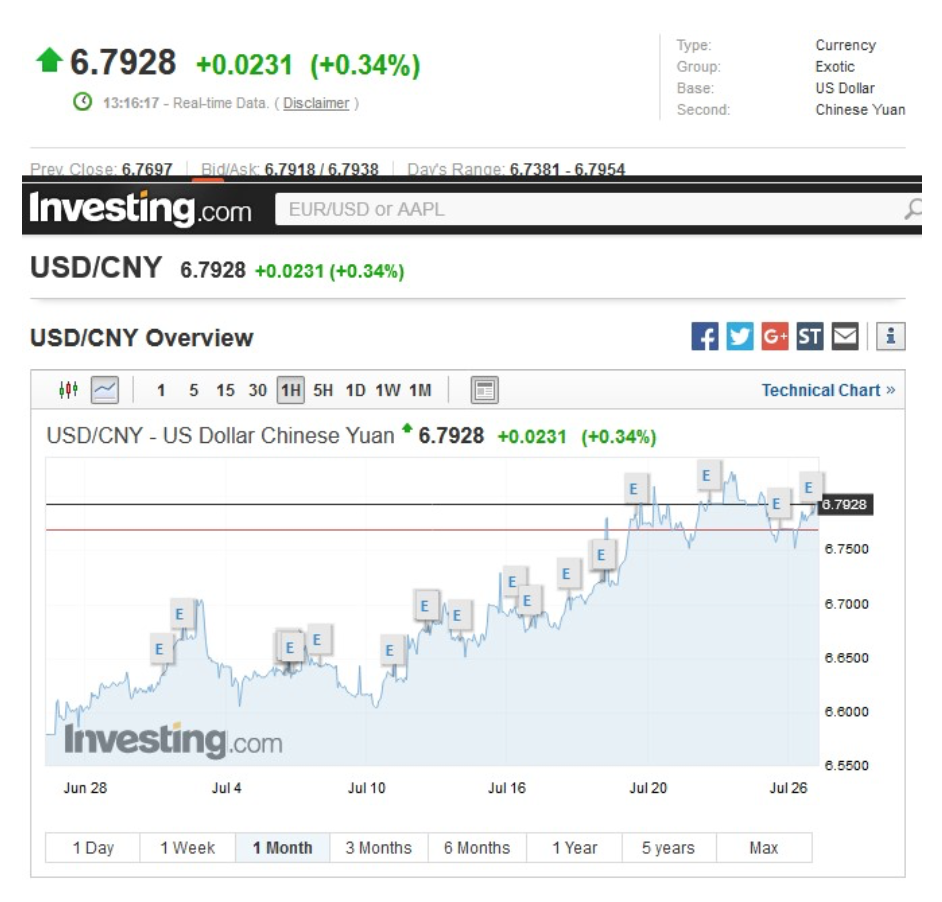

The currency recently weakened to a one-year low, prompting Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin to warn that the yuan will be assessed for signs of manipulation during the Treasury’s upcoming semiannual report on currency manipulation in October.

Meanwhile, Hussein Sayed, chief market strategist at FXTM, says that the yuan’s seemingly imminent breaking of the psychologically important 7-mark to the dollar is likely to trigger a round of panic selling in emerging markets equities and debt. The USD/CNY pair is currently changing hands at 6.79 and still climbing.

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Investing.com

Could this be a message by China’s State Council that as Trump attacks and tries to marginalize Chinese business interests, that they will now have the bank’s back. We’ve seen the “Greenspan put” so maybe we are now seeing a “China State Council put”.

The CSC (pronounced Sis-sy) Put: hey, I kinda like that. And yes, Alan the Talespinner should be smiling in his grave, but is merely smiling in his dacha.

Is $74B even ‘a lot of money?’ That’s a serious question. In relation to a $15T asset market and an economy significant multiples of that, one has to say no. It is more than usual, sure. The function could be entirely to cushion rollovers with the disruptions of a full bore trade war on, which is seriously going to impact sectors onshore in China with major ripple effects elsewhere. “Business as usual” is all I see.

The fat part of the multi-generational growth cycle in China is over, to be sure. The massive internal market in China is monetized, if not necessarily liquid. Chinese production is smoothly and very extensively integrated in world markets, both in terms of exports, commodity import sourcing, and nearly there in offshore infrastructure engagement. It’s not peak anything, there’s much room to grow, but the logistics curve has flattened its slope and won’t go steep again. Stupid easy profits are much, much harder to come by, and require more inside connections than ever within China. Part of there reason for the major offshoring of Chinese loose money was as individual capital protection, but part of it was simply a lack of solid good opportunities onshore for smaller players in many markets. That smacks of a maturing investment context.

Where we are at is exactly where the ‘deleverage gently’ policy implies: its the point where the runts and weaklings founder and get culled, and seriously bad bets get pinched out. China has prevented any kind of run or crash, in part by intelligently handling rollovers. By injecting capital &etc. The hands-off is letting dumb bets (without political inside traction) get greased, to ‘encourage the profitability of the others.’ A trade war could have far more serious disruptions for paying on debt which would be much harder to contain. What’s the best medicine there? Drive the renminbi down; which is what the financial powers are doing over there. Seems to me those folks there have capitalism down pretty solid.

Vice-Premier Liu He has the_map awareness_methinks….

Yes, the Chinese certainly have taken advantage of looking at everyone elses mistakes, their management of the economy has been exemplary for pretty much three unbroken decades now. But there is no question that the domestic debt load is way too high to be comfortable, but if anyone can manage it, they can.

I’d agree the injection looks small, I think its more the timing than anything else that looks strange. The Chinese authorities can be quite decisive, but they also don’t like rocking the boat by doing unexpected things, so this seems out of character. The huge problem they have is that all the runts and weaklings as you put it can be very well politically connected, especially at provincial level, so they have been allowed to swallow up resources for far too long. Killing them off is not easy, even in an autocracy. The longer things go on like this, the more malinvestment there is all over the country, and even the best managed economies can only look the other way for so long before you end up with (at best) stagnation and deflation or (at worst) a financial crisis.

The one thing to look out for I think is outflows. My Chinese friends complain bitterly about how difficult it is now to take money out of the country. Some are finding ways to do it, others are sitting on it at home. I suspect a lot of individual Chinese – not necessarily the rich, just those millions with some assets – are twitching to get out if things genuinely look bad. I don’t think I’ve ever met a Chinese person who doesn’t fully expect something bad to happen at some stage, hence their obsession with having a family toehold in the West – the long history of China has been long stretches of growth and stability (sometimes lasting centuries) with sudden collapses inward.

If I may interject, China has a broad millionaire financial base with a side of a few billionaires conta the American 450ish billionaire club, So how does that square both socio – political in economic terms, especially considering being a Continent bracketed by poor economic affiliates in close proximity with long logistical and information lines, considering the greater Asian – European land mass in comparison.

Especially considering the means the average American consumer finds the means to purchase stuff when it ain’t wages.

I think its fair to say that ‘wealth’ in China is functionally different than in the West, in that it tends to be spread through families, at least in name only (the rich are well aware that it pays not to be seen as being too rich – the tallest poppies tending to get cut first in a harvest, to misuse a Japanese proverb). For example, an extraordinary number of self-made rich Chinese are, by an amazing coincidence, married to, or are the sibling to, a prominent and modestly renumerated Party member.

I can’t recall the figures by now, but the gap between rich and poor now in China is rapidly going off the scale – although the actual structure of the wealth gap is probably pretty unique (as you suggest, lots of millionaires, much fewer billionaires). Most sharing of wealth occurs in families – a lot of modest middle class Chinese extended families really act almost as companies, sharing their businesses and clubbing together to, for example, finance one child to move to the US or Oz and establish themselves there. Hence a lot of property in the west is often bought by Chinese who are not by any objective standards really rich.

The other complication of course is financial repression in China, which forces saving. This has the impact of meaning there is a lot of capital floating around, while the poor repressed Chinese consumer can’t spend much. Nearly everyone thinks the way out of the Chinese economic trap is to give more money to consumers to spend, while winding down the export side of the economy (i.e. balance it from investment/export to domestic consumption). The problem is that nobody seems to know quite how to do that. Michael Pettis is a good source for detailed discussion of why this matters so much.

The politics of it of course are complex. The Chinese respect wealth, a bit like Americans do, but there is a lot of deep resentment at what they see as a nouveau riche class, specifically the children of the rich, rubbing everyones face in it. Corrupt officials are another major focus of hate (they are identified by their watches – its a big thing on Chinese social media, identifying the expensive watch brand of supposedly modestly paid officials). The Chinese government, ever alert to threats, keeps a very close eye on this, which is why occasionally some rich person or official who steps out of line finds themselves in a rather small and unhygenic prison cell.

Really don’t have any qualms with your synopsis PK and squares with my personal experiences and channels of information. Especially the – its big – and management perspective.

Perhaps it’s better to say that ‘mercan worship money. The Chinese billionaires have laundered their ill gotten gains (thru bribes) at the altars of Lord Manna in the US, Canada and Japan. Now the Chinese Govt is close the door. Kinda of late except the big boys have already moved their mullah.

Too put it another way…

Why impoverish your neighbors to forward a supply side economic agenda and then be surprised when others gain more market share by less draconian measures.

Is $74B even ‘a lot money’?…

Good question, Richard Kline. I think not in this context, although the devil is in the details. This 1-year loan facility by the PBoC is immaterial compared to the $3.2 trillion expansion of the PBoC’s balance sheet to about $5.5 trillion at the end of 2014 from about $2.3 trillion in early 2008. But perhaps the policy rationale being given for this relatively modest increase is noteworthy, as is the timing. Also of note, the PBoC’s holdings of US dollar-denominated assets appear to be in decline since 2014.

I have started to read Michael Hudson’s book “Killing The Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy”.

I just finished reading the part about the problem of compound interest which has opened my eyes to the reasons why private debt in China was a problem that needed to be controlled. I have not gotten to the part of the book that explains how a government should react when the financialization of the economy gets too large. Certainly giving banks money to lend isn’t likely to be the solution he recommends.

What I have learned so far is that the limits on the ability of our Federal Reserve to create money at will is more serious than my readings of MMT would suggest. A compound interest of 3% will bring us to the resource limit much faster than I imagined. Compound interest is an exponential growth which cannot continue forever in a finite world, especially if the interest rate is much higher than the ability of the economy to grow the production of goods and useful services.

I would love to see in the postings on Naked Capitalism, like this post, to talk more about what Michael Hudson’s book has to say about the limits of debt that should exist in an economy.

Honest question. How is 6.5% growth a “worrying slowdown?” I mean, are there Chinese economists in a room somewhere saying “Oh no! Our economy will only double it’s productive capacity every eleven years!”

Seems to me like too much growth, not to little.

It is a worrying slowdown if your entire legitimacy as a government, and likely your continued good health, depends upon sky high growth to prop up the economic expansion. The Communists once justified themselves based upon the idea that but for them Japan would invade any day. Now that has worn off and under Xi Jinping they are justifying themselves because they are destroying corruption, growing the economy, and making the country “whole” again. If one of those stool legs falls…

On a related point it is worth noting that in recent weeks they also lowered the amount of money that travelers could take out of the country from 50,000 RMB to 10,000. Even for people who are long-term residents abroad. Clearly outflows are still a big concern for them.

Nobody believes the headline figure. The real figure is something like 3%. Michael Pettis has a very detailed but clearly written post explaining why.

“Nobody believes the headline figure” sounds like an exaggeration to me. Relying on Pettis only is not a good ideal anyway.

That makes more sense, PlutoniumKun. Thank you for the answer and the link.

Also, I appreciate and register your skepticism, cbu, but it does not offer a plausible answer that makes any sense to me.

Pettis is the one who insists that China’s average GDP growth will be around 3% in the 2010s, which is in contrast to the predictions from IMF to Word Bank. In order for his prediction to be true, Chinese GDP growth has to be negative in the next few years. He sounds like a China permabear to me. Hope that makes more sense to you.

The headline figures are clearly massaged, the only question being how much. That said, the headline growth number is significantly lower than those of the last twenty years’ arc. Again, easy investment gains are done. To do anything now takes more leverage, and more risky leverage. Those myriad millionaires are well aware that they are playing with the banks’ notes, all the more reason why they are very antsy to get some of their funny money offshore into real assets which the CCP can’t touch.

Your remarks regarding the ‘family corporation’ aspect of Chinese private capital are very germane, and in fact a cultural paradigm with more than a millennia of experience behind it. The Chinese are very good at making that particular model work, and as soon as the CCP stopped ‘re-educating’ anyone who tried it the Chinese went right back to doing what they have always done.

What is happening at the top of the Chinese financial system now is very interesting and entirely different from historical norms, though. If MMT means anything, the Chinese are using a version of it, cloaked in QE worsted and necktie. This might best be a main object of study by offshore observers, but somehow doesn’t seem to get into the conversation. The concept of using MMT in the US at present seems to be to put money into the pockets of individual citizens as an entitlement, whereas in China it seems to be to put money in motion within reach of individual small scale speculators/investors, and let them make the best of it, and spread the gain around to their family networks in place of a centrally funded social safety net. Very, very clever if it works, because it will create a large and affluent middle class in China from nothing, yes—but one entirely dependent upon the central government keeping the money in motion in the financial system, and so a class utterly indisposed to any kind of revolt or agitation. The government is playing 8-d chess in this. It will be fascinating if more than a little totalitarian if they manage to succeed.

Be that as it may, the Chinese financial authorities have the firepower to keep private debt from killing the economy; the trick is not to have everything go south at one go. Yes, the Chinese are very careful about not rocking the boat nor surprising the markets as you say, and for exactly the reason to avoid panics. The hope there seems to be that ‘natural failures’ will cull the worst dysinvestment nodes, allowing the central government to avoid any blame for putting individual speculators out of the game. I don’t think that that will be sufficient myself. So a nice little ‘external crisis’ to swamp the dodgy sampans could be used well. But who knows.

China issues its own currency and has a flexible exchange rate. It can fund anything denominated in its own currency, just like the U.S. and other monetarily sovereign nations (England, Canada, Australia, Japan, Saudi Arabia, etc.) It has used “QE” with teeth to assist the private sector deleveraging which Bernanke’s QE did not do. It only worked for banks as an asset swap … good assets for marginal assets.