Yves here. It is disheartening to see the degree to which the Fed has embraced mission creep and then has proven not to be very good at it. It was bad enough that Paul Volcker weakened the Fed’s commitment to full employment by taking the position that any inflation is too much inflation, and using construction wages as his measure. What hurts investors is not inflation per se (as long as it is not so high as to make financial statements unreliable). Investors are perfectly capable of pricing in an inflation rate of, say, 2% or 4%. What hurts them are interest rate increases, and above all, sudden and unexpected ones.

However, the Greenspan Fed cared about the stock market and institutionalized the “Greenspan put” of having the central bank run to the rescue of investors, via lowering interest rates, at any sign of trouble. This reduced the risk of investing in financial assets relative to real economy projects, increasing speculation and over-financizalization of the economy. Some economists have argued that Greenspan’s overreaction to the dot bomb era (keeping interest rates negative in real terms for an unprecedented nine quarters) made the housing bubble worse.

The latest sign of the Fed’s misaligned priorities is its view that the economy is (or at least was) strong, based on unemployment data. However, wage gains have been weak, and the reason why is that we still have high levels of involuntary part time work. The Fed tends to treat involuntary part-time employment as a short-term problem, but the San Francisco Fed’s researchers debunked that idea last April in Involuntary Part-Time Work: Yes, It’s Here to Stay (emphasis original):

The U.S. unemployment rate has held steady at 4.1% in recent months (through March 2018). This is near historical lows, indicating a very tight labor market.

By contrast, the broader measure of labor market tightness called U6 has remained somewhat elevated compared with past lows. Why? The main reason is that U6 includes individuals who are employed part time but want a full-time job—the so-called “involuntary part-time” group, or IPT, labeled “part time for economic reasons” by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Policymakers have flagged the extent of IPT work as one important indicator of the state of the labor market in the wake of the Great Recession (Yellen 2014)…

During early 2018, involuntary part-time work was running nearly a percentage point higher than its level the last time the unemployment rate was 4.1%, in August 2000. This represents about 1.4 million additional individuals who are stuck in part-time jobs. These numbers imply that the level of IPT work is about 40% higher than would normally be expected at this point in the economic expansion…

We find that the changing structural features of state labor markets have propped up IPT work in the aftermath of the Great Recession….

Changes in industry composition account for almost all of this slow shift toward increased IPT work. Rising employment in the leisure and hospitality sector and in the education and health-services sector, both of which have high rates of part-time employment, made especially large contributions to the overall change. We also found evidence that the amount of IPT work and informal “gig” economy jobs tend to move in tandem at the state level.

The shift toward service industries with uneven work schedules and the rising importance of the gig economy appear to be long-term trends that are unlikely to reverse in the near future. As such, in the absence of public policies aimed directly at altering work schedules, it looks like higher rates of involuntary part-time work are here to stay.

Now, of course, one can argue that the view that the unwanted level of part-time work is the result of “structural features” lets the central bank off the hook. But that is a tad simplistic. The power of Fed interest rate changes is not symmetrical. Businessmen do not expand just because borrowing goes on sale. They expand when they seem commercial opportunity. The only areas where dropping interest rates might lead a business to bulk up is if the cost of money is one of its biggest costs. That is most true for financial speculation. aka asset management. (In the US, because we have the peculiar institution of freely refinancable 30 year fixed-rate mortgages. lowering rates arguable leads to some stimulus via refinancings lowering housing costs and giving consumers more money to spend. But this is far less powerful that you would think. Bank fees eat up most of the benefit of reduced mortgage interest rates).

By contrast, increasing interest rates has a proportionally greater dampening effect. So the Fed can and does cause recessions, but it can’t do anywhere near as much to goose the real economy.

Nevertheless, the Fed has been champing at the bit to increase interest rates since the 2014 “tamper tantrum”. We’ve been told that quite a few people at the central bank had come to the view that QE and ZIRP were not stimulating the real economy and were creating distortions. And the Fed was particularly concerned that with rates as low as they’ve been, they have no room to drop them in the event of a financial crisis (without belaboring the apparent reasons, the Fed is visibly less keen about the idea of resorting to negative interest rates than the ECB. The prevalence of guns is no doubt a factor).

So the Fed has been looking for any plausible signs of sufficient vigor in the economy to allow the Fed to notch up interest rates without doing visible damage. Wolf Richter reads the latest tea leaves.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street

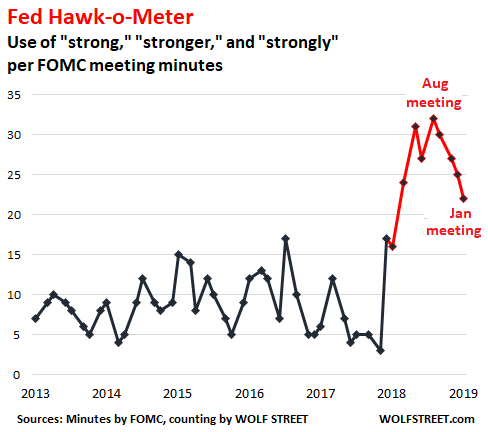

My fancy-schmancy Fed Hawk-o-Meter checks the minutes of the Fed meetings for signs that the Fed believes the economy is strong and that “accommodation” needs to be further removed by hiking rates, or that the economy is strong but not strong enough to raise rates further, or that the economy is spiraling down to where rates need to be cut. It quantifies and visualizes what the Fed wishes to communicate to the markets.

In the minutes of the January 29-30 meeting, released this afternoon, the mentions of “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” edged down for the fourth meeting in a row, this time by three points, to 22. The Hawk-o-Meter has now backed off quite a bit since the August 2018 high – when the Fed was rubbing it in that it would raise rates four times in the year – but it is still in outlier territory and redlining:

The average frequency of “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” between January 2013 and December 2017 was 8.7 times per meeting minutes. In the January meeting minutes, the 22 mentions were still 153% higher than that pre-redline average.

The average over the past 10 meetings minutes, starting with the December 2017 meeting, when the Hawk-o-Meter redlined inched down to 25.1 mentions.

Actually, “strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” were mentioned 25 times in total, but as is not unusual, two were fake strongs, so to speak, and I removed them from the tally. But they’re interesting in their own right:

One referred the to strong-but-less-strong syndrome:

With regard to the postmeeting statement, members agreed to change the characterization of recent growth in economic activity from “strong” to “solid,” consistent with incoming information that suggested that the pace of expansion of the U.S. economy had moderated somewhat since late last year.

The other referred to the sudden hair-raising spike in repo rates at the end of 2018:

Repurchase agreement (repo) rates spiked at year-end, reportedly reflecting strong demands for financing from dealers associated with large Treasury auction net settlements on that day combined with a cutback in the supply of financing available from banks and others managing the size of their balance sheets over year-end for reporting purposes.

“Strong,” “strongly,” and “stronger” appeared in phrases like these:

- “Job gains have been strong, on average, in recent months….”

- “Household spending has continued to grow strongly….”

- “Total nonfarm payroll employment expanded strongly in December.”

- “Output gains were strong in the manufacturing and mining sectors….”

- “Real PCE growth was strong in October and November” [PCE = personal consumption expenditures or short, consumer spending].

- “Available indicators of transportation equipment spending in the fourth quarter were strong.”

- “Growth of C&I loans on banks’ balance sheets picked up in the fourth quarter, reflecting stronger originations….”

- “Issuance of both agency and non-agency CMBS [commercial mortgage backed securities] remained strong.”

But “moderated” also showed up:

- “Growth of business fixed investment had moderated from its rapid pace earlier last year.”

- “Global growth had moderated.”

- “The pace of expansion of the U.S. economy had moderated somewhat since late last year.”

And the brave new world of “patient.”

“Patient” was first and feebly introduced with one just mention in the minutes of the December meeting: “The Committee could afford to be patient about further policy firming.” This has now turned into a cacophony of “patient” with 13 mentions, including:

Early in the new year, market sentiment improved following communications by Federal Reserve officials emphasizing that the Committee could be “patient” in considering further adjustments to the stance of policy and that it would be flexible in managing the reduction of securities holdings in the SOMA.

Subsequent communications from FOMC participants were interpreted as suggesting that the FOMC would be patient in assessing the implications of recent economic and financial developments.

A patient approach would have the added benefit of giving policymakers an opportunity to judge the response of economic activity and inflation to the recent steps taken to normalize the stance of monetary policy.

A patient posture would allow time for a clearer picture of the international trade policy situation and the state of the global economy to emerge and, in particular, could allow policymakers to reach a firmer judgment about the extent and persistence of the economic slowdown in Europe and China.

My take is the Fed has moved too slow toward interest rate normalization and dropped the ball. Additionally, when the stock market did it’s allowed 10% decline in December, I don’t think the much feared “liquidity crisis” issues were showing up anywhere in financial markets and yet the Fed and Powell rolled out a full court effort to placate Mr Market by halting rate increases plus talk of changes to QT allowing for a much higher permanent balance sheet and even talk or using QE more often, not less.

The Fed just didn’t need to do that. But it did do it, and the only reason I see was to boost stock prices. It worked, too.

Now the Fed is in a position that if an actual crisis does happen, it still has not raised rates much nor has it shrunk it’s balance sheet much either…so any little thing can cause the Fed to derail the progress made and even take the Fed further back from whence it started.

Granted the Fed is not much below it’s target “normal” rate of neutral, but that is below historical norm.

However, we may have to get used to a new lower normal interest rate, and much higher normal profit margin for corporations and permanent lower wages. Wages have been successfully suppressed so inflation will be under reported more often than not, allowing the Fed to permanently maintain low interest rates which will move inflation into assets not captured by government measures for the benefit of the rich and Wall Street. And the lower wages are probably now moved permanently into the profits slice of the pie.

As to your comment that “Now the Fed is in a position that if an actual crisis does happen, it still has not raised rates much”, do not fear. They are currently preparing us for negative rates – there, problem solved – we can lower rates without limit. The Fed has grown so accustomed to lying to us that it is incapable of knowing the truth. In the language of the 99% they are clearly believing their own BS. Financialization is the parasite that will eventually kill the host.

“A patient posture would allow time for a clearer picture of the international trade policy situation and the state of the global economy to emerge and, in particular, could allow policymakers to reach a firmer judgment about the extent and persistence of the economic slowdown in Europe and China.”

The problem with this is, the Fed only became “patient” when Mr Market declined 10%. The “unclear picture of the international trade policy situation” had already existed for some time.

It was when Mr Market declined 10% – and only then – did the Fed act to freeze rates and talk up more QE.

Just curious. What part of the economy does the Fed want to nurture? (It seems to suddenly have realized it cannot promote any economy without social spending, shocking.) Because it’s mandate is to maintain liquidity. (I think the appropriate word here is “profit” but they wouldn’t say it if they had a mouthful.) So it is worded as a mandate to contain inflation and promote employment up to that limit. It’s an old-fashioned benchmark. Isn’t this the Phillips Curve? The dreaded Demand Inflation? And that blasted out the window in 2008. So now they are acting like they are never going to do anything rash again. Actually “liquidity” is an inadequate concept. And interest rates are just another barbaric relic. And so on. None of their methods apply at this point because they are prevented from making decisions which might actually matter – fiscal decisions. The Fed is irrelevant. And congress has self-imposed a mandate on itself never to interfere with monetary decisions, making congress equally irrelevant. What’s a country to do?

Replace the US dollar with an international digital currency, abolish cash, negative interest rates. Worldwide. Except a few convenient tax haven countries. Tax every financial transaction automatically. Wall st happy. Most people either bleed money to banks and the tax man, or are “marginalised” into subsistance poverty. This is the elites agenda. Welcome to the new world.

The question is ,What are we going to do about it?

That’s not the question. The question is what are you going to do about it?

Me? I am going to be doing some virtue signalling while waiting for you to do something ;)

In other news, climate change is a hoax. You know why? Because Scott Adams (from Dilbert) says so: https://www.pscp.tv/ScottAdamsSays/1gqGvnVYBYBGB

So, Scott Adams is the 21st century King Canute?

He is right on one thing though – you have to talk to people in language they understand. Herein lies the problem; scientists don’t use language that non-scientists understand. And most people are not scientifically trained, or interested. The modern zeitgeist (simplistic populism) is thriving on a combination of scientific ignorance, gut feeling of being shafted and fake news presented in ten second soundbites or tweets. Communication Breakdown ( complete with the Robert Plant scream…)

So let me try:

If we don’t change the way we live the planet will be trashed, unliveable;

Your children will die from either disease, starvation or war.

Capiche?

And what am I doing? 80 subtropical acres over 100metres above sea level, and no debt.

And take any opportunity to increase awareness.

Oh, and when battery technology improves, go off grid. And I have my own potable water supply.

The sun is maturing, deal with it

The sun is an opportunity, not a threat , as far as power generation is concerned. Pity we are not yet taking full advantage and still using fossil fuels.

Very bold comments on this post.

What’s the word for pre-stagflation ?

Glad folks are already on the Titanic lifeboats.

Asia is also developing a huge advantage in economics.

The West keeps blowing it’s economies up by not understanding the dangers of Minsky Moments, the private debt-to-GDP ratio and inflated asset prices.

Australia is just blowing its economy up with a real estate bust as we speak. They don’t even know how their economy will be driven towards debt deflation afterwards as the money supply shrinks.

The fictitious financial wealth of a real estate boom will have disappeared and all that is left is the repayments on all that debt and this destroys money, shrinking the money supply (the cause of debt deflation).

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Japan did this in the 1980s and they have had plenty of time to study the balance sheet recession that follows.

Richard Koo explains:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

China has made the typical mistakes of the neoliberal era and inflated real estate and stocks with bank credit. Like the Japanese they are learning from their mistakes.

Chinese bankers had inflated the Chinese stock market with margin lending in 2015.

Set the scale to 5 years to see what happens to the Chinese stock market as their bankers inflate it with margin lending.

https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/SHCOMP:IND

The wealth is there one minute and gone the next, it wasn’t real wealth.

Chinese policymakers differ from their Western counterparts in one respect.

They learn from their mistakes.

The West:

2008 – “How did that happen?”

It was a black swan.

Oh well, never mind, let’s move on.

China:

They have already learned the private debt-to-GDP ratio and inflated asset prices are indicators of financial crises.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

The West’s “black swan” is a Chinese Minsky Moment.

To understand the US economy, you need to know what’s happening.

The FT kept going on about Janet Yellen’s inflation mystery, what is it Japanese policymakers?

It’s a balance sheet recession.

Look at the graph above, there is a huge debt overhang left after 2008 and the repayments on that debt destroy money.

This shrinks the money supply, dragging the economy towards debt deflation.

This acts as a drag on growth and keeps inflation low as it has done in Japan since the 1980s.