By Lambert Strether

I have a quarrel with the phrase “trust the science” (and in so quarreling, I don’t mean to reinforce culture war-ish talking points; I straight up disagree with the plain meaning of the words, for reasons I am about to explain). Here is a typical usage example, from the Tallahassee Democrat:

The kids join the drumbeat of public sentiment of frustration with leaders that continue to stall instead of addressing the climate crisis. After years of feeling like climate science and environmental warnings were falling on deaf ears, 2019 feels different. Perhaps 2018 served as a wake-up call and Americans are finally ready to connect the dots and trust the science.

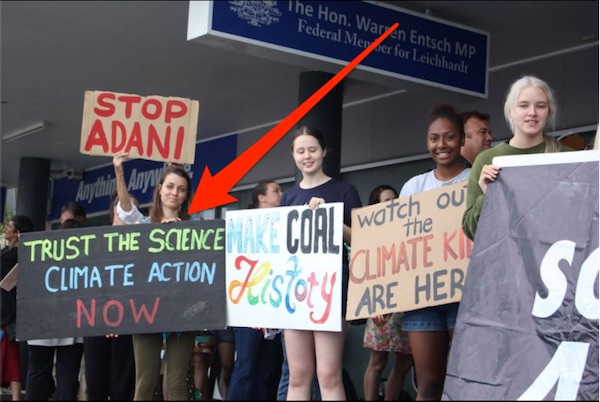

(Because who but a yahoo wouldn’t “trust the science”? We’ll get to Thomas Frank below.) Here is an example of signage:

Here’s a headline; here’s ironic mockery; search turns up numerous examples and variations (“believe science“). Here’s Joe Biden:

I would listen to the scientists.

(“-ists” will become important later.) A Republican spokesperson:

We have never ignored the science in making the very tough policy decisions required of the agency

I believe Greta Thunberg was Patient Zero. Time:

When Greta Thunberg, the youthful climate activist, testified in Congress last month, submitting as her testimony the IPCC 1.5° report, she was asked by one member why should we trust the science. She replied, incredulously, “because it’s science!”

So many people vehemently disagreeing with each other, all the while trusting science; and so many people not trusting science at all. Perhaps “trust the science” is not all that meaningful? My concern, as I said, is with the plain meaning of the phrase: There is no “the science” (with definite article) because because progress in science is based on conflict, and you have to pick a side (and there may be more than two). Similarly with “the scientists,” as Biden would have it. Which ones?

So how is science done, and how is progress in science achieved? I may be showing my age here, but I believe that Thomas Kuhn, in the Structure of Scientific Revolutions, gave a very good account. Excerpting from Kuhn’s entry in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Kuhn paints a picture of the development of science quite unlike any that had gone before … [Kuhn] claims that normal science can succeed in making progress only if there is a strong commitment by the relevant scientific community to their shared theoretical beliefs, values, instruments and techniques, and even metaphysics. This constellation of shared commitments Kuhn at one point calls a ‘disciplinary matrix’ (1970a, 182) although elsewhere he often uses the term ‘paradigm’. Because commitment to the disciplinary matrix is a pre-requisite for successful normal science, an inculcation of that commitment is a key element in scientific training and in the formation of the mind-set of a successful scientist. … A mature science, according to Kuhn, experiences alternating phases of normal science and revolutions. In normal science the key theories, instruments, values and metaphysical assumptions that comprise the disciplinary matrix are kept fixed, permitting the cumulative generation of puzzle-solutions….

Here is an example of “normal science,” from Quebec’s The Suburban, “Trust the science on COVID-19, but much is still not known,” from chemist Dr. Joe Schwarcz, Director of the McGill Office for Science and Society:

In the long run, we have to trust the science, but unfortunately, science does not progress by giant leaps and bounds — only the quacks can do that. Science progresses by a series of small, careful steps, but eventually it will put us on the right track.

Back to Kuhn:

….whereas in a scientific revolution the disciplinary matrix undergoes revision, in order to permit the solution of the more serious anomalous puzzles that disturbed the preceding period of normal science. A particularly important part of Kuhn’s thesis in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions focuses upon one specific component of the disciplinary matrix. This is the consensus on exemplary instances of scientific research. These exemplars of good science are what Kuhn refers to when he uses the term ‘paradigm’in a narrower sense. He cites Aristotle’s analysis of motion, Ptolemy’s computations of plantery positions, Lavoisier’s application of the balance, and Maxwell’s mathematization of the electromagnetic field as paradigms (1962/1970a, 23). Exemplary instances of science are typically to be found in books and papers, and so Kuhn often also describes great texts as paradigms—Ptolemy’s Almagest, Lavoisier’s Traité élémentaire de chimie, and Newton’s Principia Mathematica and Opticks (1962/1970a, 12). Such texts contain not only the key theories and laws, but also—and this is what makes them paradigms—the applications of those theories in the solution of important problems

(For awhile, one was seeing “paradigm shift” in every book in every airport bookstore business section, when we were going to airports; what most of these books didn’t understand was that a paradigm applies across a discipline, and not simply within a firm. Nor is it possible to induce a paradigm shift simply by proclaiming it, sadly for motivational speakers.)

Interestingly, we’re seeing an example of such a paradigm shift, and the resistance to it, in the COVID-19 crisis, in the droplet vs. aerosol transmission controversy. Vox explains:

[In a 1932 paper, William Wells] outlined a clear distinction between droplets and aerosols according to their size. Big drops fall, and little aerosolized drops float.

That is the paradigm. Here comes the paradigm shift:

It’s now appreciated that the actual picture is a lot more complicated.

“We’re always exhaling, in fact, a gas cloud that contains within it a continuum spectrum of droplet sizes,” says Lydia Bourouiba, an MIT researcher who studies the fluid dynamics of infections. And, as she explained in a March paper in JAMA, the conditions of the cloud itself can affect the range of some of the droplets. If propelled by a cough or sneeze, Bourouiba finds, droplets can travel upward of 20 feet. “The cloud mixture, not the drop sizes, determines the initial range of the drops and their fate in indoor environments.”….

There’s growing theoretical evidence for the airborne spread of the coronavirus. Lab studies, in idealized conditions, also show that the virus can live in an aerosolized form for up to 16 hours (the scientists in this case intentionally created aerosolized droplets with a machine).

Multiple studies have found evidence of the virus’s RNA in the air of hospital rooms. But the WHO notes “no studies have found viable virus in air samples,” [no longer true] meaning the virus was either incapable of infecting others [no longer true] or was in very small quantities unlikely to infect others.

“What we are trying to say is, well, let’s not worry about whether you call it aerosol or whether you call it a droplet,” Morawska, the co-author of the recent commentary imploring….

“Imploring” because “the key theories, instruments, values and metaphysical assumptions that comprise the disciplinary matrix are kept fixed.”

… the WHO and others to address airborne transmission of Covid-19, says. “It is in the air,” she says, “and you inhale it. It’s coming from our nose from our mouths. It’s lingering in the air and others can inhale it.”

That the WHO updated its language is a sign that it’s starting to appreciate [“kept fixed”] this perspective. (That said: The WHO still defines [“kept fixed”] a droplet as a particle larger than than 5-to-10 microns, and an aerosol as something smaller, despite many scientists arguing the cutoff is meaningless.)

So, when we say “trust the science” in this context, what can we mean? Which paradigm — “a science” — do we select? (I exercised what I consider to be my critical thinking skills, and went with the aerosol transmission paradigm, and adjusted my personal practice accordingly.[1])

A second difficulty with “trust the science” is that it shifts over very easily to “trust the scientists” (as it did with Biden) and then, in our partisan era, to “trust this scientist.” For example:

As seen in Columbus, driving home from getting my #BidenHarris sign: #TrustFauci (and #TrustScience ?). pic.twitter.com/FHhklACvKE

— Syl ? Vote Out Hate. (@GrnYze) August 26, 2020

Another example:

Trust science. Trust #Fauci. pic.twitter.com/26rixuRMjQ

— @starfish (@starfis13730178) August 1, 2020

A final example:

2) Trust Fauci => Support science: https://t.co/z33s1r026f (no personal profit) pic.twitter.com/FI3bcUFy1i

— Eric Feigl-Ding (@DrEricDing) May 28, 2020

This last example, of “Fauci” screen-printed onto masks, is especially ironic. As I wrote back in June:

About masks:

What should public health experts have done instead? Could have leveled with public "masks are important, but avoid hoarding to ensure medical staff have enough." Could have pushed for cloth/homemade mask wearing by public instead. Could have pushed for mass production.

— Arpit Gupta (@arpitrage) June 23, 2020

Lambert here: To my shame, I bought into — and worse, propagated, told readers and friends — the original LIE propagated by Fauci and WHO, that masks were not necessary. Fortunately, I continued to do my homework and watch the news flow, and changed my mind (and my practice). Fauci and WHO perpetrated what Plato called a “noble lie,” [UPDATE See also contemporary philosopher Leo Strauss] believing that the best way to make sure that medical personnel — and they, too, personally — had masks was to make sure the public they duped didn’t buy them up, and so they used their authority to lie about whether masks worked (they do). In an election season where the liberal Democrat pitch seems to be “Let The Professionals Take Charge Again”™, having top PMC and global agencies get caught out in a Noble Lie might not have been the greatest idea. And as we few, we happy few in the Blue States make fun of the fat stupid loud people in the Red States who don’t trust the experts that lied to them, we might consider whether our Noble Lies have unexpected effects, not merely politically, but in the destruction of the very concept of public health. Sorry about that.

Sometimes, critical thinking can be painful. But, sadly, there’s no particular reason to lend one’s trust to scientists while surrendering it. Thomas Frank writes:

These days, right-thinking Americans are tearfully declaring their eternal and unswerving faith in science. Democratic leaders are urging our disease-stricken country to heed the findings of medical experts as though they were the word of God….

Unfortunately, it’s all a mistake. Donald Trump’s prodigious stupidity is not the sole cause of our crushing national failure to beat the coronavirus. Plenty of blame must also go to our screwed-up healthcare system, which scorns the very idea of public health and treats access to medical care as a private luxury that is rightfully available only to some. It is the healthcare system, not Trump, that routinely denies people treatment if they lack insurance; that bankrupts people for ordinary therapies; that strips people of their coverage when they lose their jobs — and millions of people are losing their jobs in this pandemic. It is the healthcare system that, when a Covid treatment finally arrives, will almost certainly charge Americans a hefty price to receive it (3).

And that system is the way it is because organised medicine has for almost a century used the prestige of expertise to keep it that way.

Bowing down before expertise is precisely what has made public health an impossible dream.

Is there a way to respectfully leverage the expertise of scientists — some of whom are truly in it “for the love of the game,” let us not forget that — without bowing down? I would, again, urge that critical thinking skills are the anwer.

Sadly, we as a society and policy do not seem to inculcate critical thinking skills very well. How to do better? I would like to see, well, a paradigm shift from “Trust the science” to “Do the science,” because I think that is an operational capacity that an informed citizenry should have. (We see this all the time when ordinary working people become subject matter experts to fight pipelines or landfills, or save lakes, or become involved in long legal battles with corporations that have poisoned them and their environs). We should encourage this capacity. One easy way would be to remove all paywalls from scientific publications, and have the Federal Government pay the rapacious publishers a reasonable sum. Those same publishers should include, besides Abstracts, a “Plain Langauge Summary” in their editorial designs. We should also fund a great deal more citizen science, ideally under the aegis of a Jobs Guarantee. With climate change barreling down upon us, there are innumerable observational studies that should be performed.

NOTES

[1] There is also a paper which I could not retrieve, which argues in summary that hospital personnel are triggered by the word “airborne,” because to them it means a germ that’s wildly contagious, like measles or worse (which COVID is not), and they have to take a lot of measures accordingly, like moon suits or whatever. This is another example of a disciplinary matrix or paradigm.

If the mask issue was about lack of resources then that may make the lie “noble”. But how will you explain the HCQ scandal that will surely erupt into the mainstream press as it becomes obvious that an effective and cheap medication was deliberately banned by the relevant authorities on entire spurious grounds.

> If the mask issue was about lack of resources then that may make the lie “noble”

That was the issue, but when the foundation of the medical advice you give to the public is a lie, that means any sensible person should give consideration that you’re lying all the time, at least on serious issues. When it comes time to introduce the vaccine, who will have any credibility? And could they not have forseen this?

They should have leveled with the public. And the fact that both Fauci and WHO did the same thing shows the issue is systemic (as in “casual lying.” Everything is like CalPERS).

It’s Lucy and the football.

Fauci should step down as he blew his credibility and treated the public with an elitiest’s contempt– “no masks” was the hill that he chose to sacrifice his personal and professional integrity upon.

Hang him with the rest.

Making ones own mask is easy. They could have told people to make their own masks. It is not like a mask is high tech. Flannel or analogous tightly woven material would make a pretty good mask. A double layer allows one to put a vacuum cleaner back sheet between for extra filtration. A cut off stocking helps it seal to the face far better than commerical ones. Fauci did not really know at the time, it seems. He did not want to spout information that was speculative. Had everyone worn a mask from the start all of this misery would have been unnecessary as the Ro would have been less than one.. This mess is self inflicted. In retrospect there should have been some sort of significant financial penalty for not wearing a mask. Here in Germany a store will be fined 3000 Euro if a customer goes in without a mask.

The HCQ story should be a front page embarrassment. The 2 formerly prestigious institutions that canceled their trials were basically poisoning their patients. HCQ has been around and used for decades. The established dosing guidelines are typically in the ballpark of 200-400mg per day. The. WHO & Oxford trials were dosing 2000 mg on day one and 800 mg on the following days. It is a well known side effect that excessive HCQ can cause heart disrythmia and renal failure. Several other studies, including a recent Belgian one with over 8,000 patients, that dosed within established guidelines typically found about a 30% reduction in mortality.

The article talks about 2 very different topics.

Climate Change and Convid-19

When there is a vote over 50% wins, over 65% is a supermajority. Regarding the the “vote” on Climate Change 99% of qualified (meaning they have a related degree in the appropriate science ) scientists and 97% of qualified “peer-reviewed” studies BOTH say the Climate Topic has reached a level where no more debate is necessary.

There are few if any other topics which have such a high majority – it is far higher than the need to debate to do so is simply delusional.

The world’s scientists have been studying Climate since the late 1950s and NASA and the world’s leading Climate Research group (at Exxon Mobil believe it or not) told President Johnson in the white house that this was a huge danger and had to be addressed and that was 52 years ago and to date we have done very little – now it the time for accelerated efforts worldwide the clock is ticking and time is NOT on our side.

Convid is another matter – we know very little about it, compared to Climate and there is still valid debate as to what should be done – at this time it looks like isolation is the most effective until a true tested vaccine can be developed.

Any true (scottish) scientist would tell you that science is more likely to be right than the alternative, but that we’re always learning. Implicit is that we are therefore often wrong, even with the best science.

But on average (not always useful) across the long term (no help now), and across multiple subjects (not great for this one thing) scientific understanding will be more correct than whatever narrative bullshit is floating around as aerosols and droplets.

Speaking of which, that’s an interesting example. I’ve been learning that every field is full of that kind of weird and wrong categorisation, that is nonetheless a useful model for analysis.

Right down from the big guns like biological species concept (plant guys knew this was batshit from the get-go) to silly-but-critical stuff like what defines sandy vs dirty vs silty soil. All these arbitrary quantitative borders are really kinda useless lines through a gradual fade, and i suspect the originators were clear about this. But they then get applied as rules by less clear thinkers, and trouble happens.

marvelous comment, the second paragraph is brilliant!

Thanks, I’m glad it made someone happy :)

The key thing to realize about categories is that they are created to simplify the thoughts of the people using them. By their very nature categories obscure complexity, especially those nagging little things that just don’t fit neatly into some category. Of course those little things that don’t fit are often the source of scientific progress, so the key is to know when something doesn’t fit, and then to understand why.

As George Box said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Which Milton Friedman corrupted into (I paraphrase) “It doesn’t matter how silly or unrealistic your assumptions are, if the model produces the result you want it’s right.” I loathe that man.

> every field is full of that kind of weird and wrong categorisation, that is nonetheless a useful model for analysis. Right down from the big guns like biological species concept (plant guys knew this was batshit from the get-go) to silly-but-critical stuff like what defines sandy vs dirty vs silty soil. All these arbitrary quantitative borders are really kinda useless.

Oh, I agree. I used to put things in buckets for a reason, it’s “useful but wrong” (or right enough) all the way down. (I believe that the later Kuhn reframed his paradigm concept in terms of categories, but I find the idea of the paradigmatic, repeatable experiment really, er, useful, so I went with the early Kuhn).

I can’t quite come up with the quote, but I read somewhere recently that only the singular is real. Plurals are an illusion.

Useful but wrong is a good way to think about…. well I guess everything.

Not sure I buy it on the singular being real either, been breaking my head trying to understand what separates a unicellular from a multicellular organism down at the bottom edge where the small-n multicellular critters hang out. But I might also be excessively cynical…

Thanks for that. I wouldn’t give up being “excessively cynical…” if not the real thing.

Re: Only the singular is real

That reminds me of when I was doing quantitative market segmentation – giving quantitatively derived clusters pretend names like “budget sensitive”, “quality focused”, “status aware” and so on. The variance within a cluster was large and the likelihood of misclassification so high that we fiddled our accuracy metric by scoring “+- one cluster” as a win ( shades of the UK grading fiasco ) to make it respectable.

I used to end my pressie singing the praises of analytics and talked about the day we’d be marketing to segments of size 1 !

Is ” the species” as batshit for animals as it is for plants? If it is not . . . if animals really do come in mostly self-contained breeding populations which mostly can’t produce reproduction-worthy progeny between these populations . . . . and the “species” concept is a good conceptual word for that bio-fact about animals, then it would be unfair to expect the animalists to consider the “species” to be “batshit” if in fact for them and their animals, it isn’t.

How many animals come in “hybrid swarms” between bunches of “species” the way some plants do?

Enough animals get away with it that there is a concept of “hybrid zones” to do with the overlap where the merging species are visible as a gradient (or something like that, not an expert). It’s true that plants are way better at getting viable populations out of hybridisation than animals are, because they can fertilize themselves to get past the popn=1 stage.

However, plants and animals make up a tiny tiny slice of all the life on earth. BSC also doesn’t work very well for anything that reproduces asexually. So it’s a great concept that only works for specific contexts that are quite limited and getting moreso, but it has been commonly understood to apply to everything. That’s how these kinds of categorisations fail – edwardo described it well up above.

In the post-molecular biology world denoting species based on the minimum group that has DNA similar to an arbitrary value is probably as good or better, but its a pig to try and use for communication.

The hesitance of the WHO to accept aerosol virus transmission or airborne or whatever you want to call it and stick to the only droplets & fomites theory is somehow astounding. Contact tracing analyses, contagions in closed environments and super-spreading events should have made them very suspicious about airborne transmission. At least they should have avoided to keep too dogmatic and leave an open door to alternatives.

I have seen a few cases of scientists being dogmatic. I remember a case presenting a hypothesis with lots of supporting experimental evidence only to be later defeated by overwhelming contrarian evidences… so it look this scientist designed the experiments, possibly inadvertently, to be in agreement or to demonstrate the hypothesis being defended only to find that experiments done by other scientists crushed a theory that was built with so much patient and comprehensive work. What Mr. Strether says here, that Science progresses through confrontation of hypotheses is quite true and when you get close to the limits of knowns and unknowns you have to be open minded and not dogmatic.

As I recall, that article traced the reluctance to identify the virus as airborne back to the fear of reanimating the miasma theory of illness, the dominant paradigm until sometime in the second half of the 19th C when the work of Pasteur ushered in the era of the germ theory of illness.

These noxious vapors were believed to be the cause of the Black Death (which we now know was rats) and up until fairly recently in the grand scheme of things this theory led to million of deaths from cholera, smallpox, and other diseases.

And that’s kind of a useful example as far as how we get things so wrong when using scientific knowledge in a practical, social setting.

Scientists didn’t decide that all noxious fumes are safe because little animals are to blame. What they worked out is that its not the fumes that are dangerous, it’s the animacules that are sometimes in them – and are also sometimes on or in other things that aren’t fumes.

Both, depending on circumstance, but not one or the other. In some ways it’s the believing it can be reduced to simple either/or thinking, the false dichotomy applied to policy, that generates millions of deaths.

And you know, now we know about bacteria and viruses and fungal pathogens and a whole bunch more stuff that reinforces the value of the germ theory. But despite all the learning, policy is still way easier to formulate and enact if it’s simple and black and white, with no grey fuzzy areas at the edges.

> As I recall, that article traced the reluctance to identify the virus as airborne back to the fear of reanimating the miasma theory of illness, the dominant paradigm until sometime in the second half of the 19th C when the work of Pasteur ushered in the era of the germ theory of illness.

I remember that article, and I should have incorporated it (though I’m too lazy to find the link). The miasma theory was a losing paradigm.

That said, when you have at least two studies where (from memory; Ignacio would do better) the virus is actually collected from the air (and on windowsills, having arrived there via the air), and then the viral matter turns out to be capable of infection, the miasma theory doesn’t accurately describe the claims.

I believe that the reluctance to accept airborne transmission might have to do with the recommendations of the WHO to control Covid. Once you accept it, control measures might have to be changed and some economic activities wold result more damaged.

Haven’t we seen some articles on NC about effective safe UVA filters suitable for incorporating into aircon systems? Seems like an economic opportunity, yet another excuse to tear down and rebuild some existing infrastructure and make a margin going both ways.

Perhaps Gebreyesus and his top lieutenants were secret Chinese agents who were manipulating the science and lying about what was known in order to facilitate the spread of corona throughout non-China so as to give China a head start in winning the New Global Hegemon race?

One easy way would be to remove all paywalls from scientific publications, and have the Federal Government pay the rapacious publishers a reasonable sum.

And remember Aaron Swartz. Thanks, Obama.

I thought of Swartz when I wrote that, but it was late and I was moving fast….

From an article by the professor of Italian (and musician) Alessandro Carrera, who teaches at the University of Houston. He is describing what he sees as the death-seeking despair in the U.S. working class:

Sono disposti a credere a tutto tranne che alla scienza, perché la scienza (quando l’ho detto ai miei studenti sono rimasti sorpresi) ha sempre torto. La scienza non è l’informazione che ricevi oggi e che domani sarà superata da un’altra informazione. La scienza è un processo, non un fatto e nemmeno un dato. Ma questi sono discorsi da laureato e non gli è mai venuto niente di bene, a loro, da chi aveva una laurea in tasca, come è tristemente vero che per loro non cambierà molto a novembre (se ci arriviamo), non importa chi vincerà le prossime elezioni (se ci saranno).

As he writes: I surprise my students by telling them that science is always wrong (students are shocked, others may have their “beliefs” confirmed) because science is a process, not a fact, not even a datum. But as he says, this kind of discourse is lost in the general despair.

Americans “believe” too much. Science isn’t about belief, nor is it about trust. Science is about examining observations and data. No one who is scientifically minded “believes” in evolution–one looks at the data and observations and color changes among moths and accepts that the data make sense. Which all of us can do.

> Which all of us can do.

Yep. The relevant movie is Erin Brockovich (but it happens in real life too!).

Science is not about belief or trust indeed.

But unless you can replicate all from point zero, you have to take some parts on “faith”. Say if you are an electronics engineer, would you really expect to replicate all the high-energy physics experiments which confirmed the basis for your work? Or will you just take the papers on it, and only come back if something doesn’t work as the papers say it should?

You’re absolutely right . For us ordinary mortals it’s all about trust. When I get into an airplane i put my trust not only in the science of flight, which I don’t understand, but in the pilot, the people who maintain the plane, the workers who built the plane, the engineers who designed and set specifications for the plane, the government agencies/workers for monitoring and certifying that everything is right. It involves a huge quantity of trust in people and process.

I think a better way to put it was written by Gregory Bateson, in Steps to an Ecology of the Mind. “Science doesn’t prove anything.” A good example is the protagonist in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, who is mentally ill and unable to deal with the truth that scientific “truth” is always subject to change.

We should also fund a great deal more citizen science, ideally under the aegis of a Jobs Guarantee. Lambert

Like when the Soviet Union promoted Lamarckism over Mendel wrt genetics?

Why not just give people the means to not be wage slaves and many will choose to be scientists? Like Franklin and many other scientists of independent means? And unlike Einstein who had to waste a good deal of time working at a patent office?

So why is that impossible in the 21th Century when the problem of production was solved during or before Keynes’ time?

Lamarck wasn’t totally wrong. Darwin wasn’t totally right. We are now finding out that traumas to human parents affect their children *genetically* for several generations. Science is a process — observation, hypothesis, testing, thesis. Observe, rinse, repeat. It goes where it goes, and it goes where it works. Currently, we have a govt that ‘trusts’ the markets, and how is that working out for us?

“Why not just give people the means to not be wage slaves and many will choose to be scientists?”

now we’re talking!

I do science all the time, out here on the farm…observation, over time, of various systems…offering myself hypotheses when applicable, most of which turn out less than “Right”.

and applying all manner of potential solutions to whatever problem needs solving, and seeing what works…or, more often, what works well enough, that can then be improved on.

like the clear rubber hose, full of water and a drop of bleach, that brings sunlight into the scary part of the shop where the nuts and bolts and such are kept.

or talking wife into being observed so i could figure out how to position the “urine diversion apparatus” in the composting toilet(turns out i had to “reposition the subject”, instead: females have to sit upright for it to function properly…like the signage now says)

or obtaining a mess of barometers to test various hypotheses regarding my weather pain(it ain’t just air pressure)

I’m only able to pursue this sort of insanity because i’m disabled, and unfit for the kind of work available around here.

Ie: leisure(and necessity, due to being poor)

Your example of Franklin is perfect…as is that of Jefferson(my own model for so many things)

Just having the time to muck about, and fail repeatedly…without that failure causing immediate penury.

That certainly squares with my experiences in running a small farm. Mistakes are our greatest instructors, but only if we can keep affording to pay for the lessons! I was just complaining to my father about the amount if reinventing the wheel we have to do around here, the lost cultural knowledge, the banishment of such valuable folkways by the industrial project. If he hadn’t left the subsistence farm to attend university, I wouldn’t have had to figure all this stuff out again!

> Why not just give people the means to not be wage slaves and many will choose to be scientists?

A Jobs Guarantee is “a job for anyone who wants one.” Something wrong with giving workers more control over the workplace?

What did the Soviet decree that Lysenko’s Lamarckism would be the only permitted theory of genetics within the Soviet Union have to do with citizen science as Lambert has described it? What does your example have to do with citizens running cheap little experiments and/or gathering cheaply-gathered observational data?

The idea that ‘trust science’ shouldn’t be absolute can be seen in Planck’s Principle (science advances one funeral at a time). Yes, when done well it can bring us closer to understanding underlying truths that are based on laws of physics or nature rather than the biases, prejudices and preconceptions of all the scientists concerned. But the answers it gives us are often conditional, provisional, heavily qualified, and/or subject to change as new information and results come to light. We are also reliant on scientists to describe and interpret it for us, which presents the risk that they may insert their biases, preconceptions etc. back into the discussion.

Critically assessing all of this takes work, and a lot of people don’t want to bother. They’d rather nominate a prophet or oracle and believe in them absolutely. You can see this in the personality cults that have sprung up around the top scientists or health officials in various countries.

Great stuff, Lambert!

My rules on science and scientists after 45 years in the trenches. YMMV.

Rule #1: When reading a contribution to the primary scientific literature, first check the acknowledgments to see who paid for the work. One famous/infamous case (out of hundreds, probably thousands) from a talk I gave on the Diet-Heart Hypothesis listed sources of support (grants, contracts, honoraria/bribes) for the authors of a paper about statins: Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, ScheringPlough, AstraZeneca. Why would anyone believe a single word? Mary McCarthy on Lillian Hellman comes to mind.

Rule #2: Read the Abstract/Summary last, not first. This is the last part written by a team of good scientists, and it should be the last thing you read, too. A corollary is that most journalists read only the Abstract.

Rule #3: Yes, trust the scientists if you determine they are trustworthy. In my relatively long experience, most are even though their conclusions are necessarily provisional, even wrong. But see Rule #1. Another corollary: When someone argues that Dr. Whathisname graduated #1 in her class at Harvard/Yale/Princeton/Berkeley/Johns Hopkins, and therefore should be believed, remind your interlocutor to read The Best and the Brightest by David Halberstam.

And yes, abolish paywalls for publicly supported research! Ignore the other kind, most of the time.

As a personal aside, Thomas S. Kuhn indeed made a big splash with The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (and the update published in 1970, which I read in 1974-75). Paradigms, paradigms, paradigms, shifting paradigms! In my days as a New York-ite, card-carrying Leftist in the late 1970s I heard way too much about TS Kuhn, whom people actually read even less than Piketty. Yes, theory determines which questions can be asked, but it doesn’t have much to say about whether a particular question is intelligent, or really whether the theory itself is correct. Sometimes yes, sometimes no, sometimes yes and no. Kuhn manifestly works better with physics than biology, but dogma is the bane of both. For those with access to a good library and time for a relatively quick read during the current crisis, the filmmaker Errol Morris has written one of the funniest and most well-designed, if recondite books, I have ever read, The Ashtray (Or the Man Who Denied Reality) about TS Kuhn…When Morris was a graduate student in Princeton, Thomas S. Kuhn, of the Harvard Society of Fellows and a denizen of the Institute for Advanced Study (professional home of Albert Einstein), threw an ashtray (full) at Morris. With malice. Professor Kuhn apparently didn’t take kindly to an impertinent graduate student who doubted his genius. Perhaps not all that unusual, but for the flying ashtray…Authority often insists on its privilege. When that happens, ignore it.

If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.

So in Melbourne you had some fat 76 year-old dude organizing Freedom Days where people without masks ‘go for a walk’ in the same area at the same time. This guy was definitely not interested in science and when interviewed, was wearing an anti-vaccer t-shirt. I invite people listen to what Victoria Police Assistant Commissioner Luke Cornelius had to say about the whole thing in a 44-second clip on the following page-

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8672875/Melbourne-police-slam-tin-foil-hat-wearing-76-year-old-arrested-planned-anti-lockdown-protest.html

Great vid, cheers Rev.

Is the “sovereign citizen” and “mah constitution” bollocks really a thing in oz? I’ve heard a couple of extremely loose units try it on in NZ but they just baffled people into ignoring them. Some crazy just doesn’t import nearly so well.

Maybe the Royal Society will change its motto from “nullius in verba” to “trust the science”. But I doubt it.

Chemistry was a pretty tough class. I can only imagine trying to learn it 255 characters at a time.

There is a long distance between “trust” the science and “do” the science. Indeed, this article is in that gap, as it tries to explain the science. Most of us lack the tools and skills to “do” the science in all but the most basic situations.

One of my frustrations with the 97% of climate scientists who argue from authority to “trust” the science is that they skip even an elementary effort to explain the science. (Or am I blaming the press?) Not even the Pope can convince using the argument from authority, and plenty of Popes have tried. Anyone who can understand night vision goggles is halfway to understanding global warming. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane interact with infrared radiation, and keep the earth warmer. Even simpler, another powerful greenhouse gas is water vapor. Everyone knows the difference between a cool dry night and a hot humid night. Explain the science. For an example of how this can be done, see this short video.

100% agree with you.

Craig, unfortunately you can find hundreds of videos and texts on the Internet giving equally plausible arguments for why more CO2 won’t heat the planet to any significant degree. To determine who is right requires a lot of work, Or you can trust the scientists, not an individual scientist where you can pick one who happens to believe what you want to believe, but scientific organisations like IPCC or WMO.

>Everyone knows the difference between a cool dry night and a hot humid night.

I think you’re inadvertently disproving your own point here. The reason a hot humid night feels so hot is because the humidity reduces the evaporation of sweat on your skin, causing you to feel warmer. It’s not because of the humidity’s greenhouse effects. If you were to attempt to draw any conclusions from this premise, how accurate could they possibly be? Is that better or worse than trusting someone else?

The fact of the matter is that real science is hard as fuck. Citizen-science is a pipe dream and you (and Lambert) are way off-base in imagining that an average -or even exceptional- citizen can make a meaningful contribution, or even fully understand the principles behind, science as difficult as “epidemiology of a novel coronavirus” or “global climate change.”

Trusting scientists is exactly the correct behavior for someone with enough awareness of their own limitations to understand that they will *never* fully understand the science enough to draw their own conclusions.

But won’t that advice be abandoning people to trust the corporate junk science behind genetic engineering ( GMOing) and Roundup and so forth?

Like it or not, we’ve already been abandoned. I wasn’t trying to give advice but rather describe how things are. In the year 2020, we are all at the mercy of a whole host of individuals and institutions. They routinely fail us. I want us to focus our wrath on those who truly deserve it: the people who were given positions of trust and abused that trust. Anything else is victim-blaming.

Trust is an absolutely essential part of society, science, and public institutions.

It doesn’t matter how many degrees Fauci has and how much he dominated academically.

He is in a public servant role and whether the public can trust him is his #1 job competence, not his academic chops. His wasn’t a noble lie, it was a stupid, arrogant, incompetent, and reckless lie. He should have been fired on the spot. He made himself worthless and substantially undermined the effectiveness of ANY future measures that the gov could take.

Same goes about WHO.

Hard to believe but those are the kind of idiots that are supposed to watch out for this country’s and the world’s health.

PS. re “removing paywalls from research”, some have taken that in their own hands — try sci-hub.

+100

I don’t know whether there is such a thing as a noble lie, but this lie was not noble. Fauci lied because he figured he and his buddies in the (mostly for profit) health care industry were more “essential” than the rest of us, and he knew they had done a terrible job of preparing for this situation at every level.

I understand the operational need to keep the health care workers from all getting sick, but there was 0% possibility of this lie holding up and working out well over time. There was basically 100% probability that it would further destroy trust that was needed to manage the pandemic in the long run.

If there was any nobility to this lie at all, it will only be if it helps future Americans wake up to the profound corruption of all our institutions and move toward something different.

> I understand the operational need to keep the health care workers from all getting sick, but there was 0% possibility of this lie holding up and working out well over time. There was basically 100% probability that it would further destroy trust that was needed to manage the pandemic in the long run.

Yep. And the PMC sending the message that “We are more important than you!” is a little too on-the-nose (even if in this narrow case it’s true). All that foofra about heroic “essential workers” and then denying them what they most need (with a lie as the explanation).

TBH, the mask stuff was idiotic – but easy to fall for. You’re not alone, I did fall for it as well and suspect a lot of others.

With a hindsight, there was a couple of crucial pieces which I still wonder how I could have overlooked:

– if masks don’t work, why do health workers need them in the first place?

– when there was no pandemic, why did healthworker use masks in the first place?

The first is sort of self-obvious, and should have been a “duh” straight away.

But the first answer is actually sort of related to the second one which is a bit more complex – the healthworkers wear the masks to protect the patient, not themselves. The surgeon washes his hands to primarily protect the patient, not himself. The tools are sterilised to primarily protect the patient, not the doctor. Or put it differently – up to mid 19th century, the halmark or a good doctor was blood stiffened apron, and Semmelweis who said otherwise was considered a weirdo (at best) – but doctors weren’t the one who died from treating their patients in those conditions.

There is, of course, part of protecting the healthworker, but it’s more incidental than anything else. When they do operate in really dodgy environment, it’s not the mask, it’s a full PPE stuff they need. A mask ain’t gonna save them from Ebola.

You see this is what not trusting (your own eyes) vs. expecting someone to show you the way is all about. Where to start? Let’s see… media was responsible for showing early on entire countries gorging on mask and I mean everyone nine to ninety in lockstep wearing them. It doesn’t take a lot of critical thinking skills to determine maybe; just maybe the rest of the world might be on to something here. So there is this blame game going on in our country where personal responsibility was put on hold until specialized influence enhanced outcome.

When the core ruling premise is that there is no society and that markets control all, there is innate bias that results in profits overriding everything else including human life. Truth, reality and science get lost. A second civil war between globalist and nationalist oligarchs on American soil is starting. Both clans ignore controlling the pandemic, ending the economic depression or calming the fears that are driving the unrest. Right now it is at the sniping stage. Donald Trump will incite more rioting to stay in the White House and blame his global Marxist opponent as the cause. Barricades are next, then ambushes. Only the restoration of community, truth, science and democracy can avoid open warfare and the end of the United States.

Another quip about science is that it makes progress one

funeral at a time. When the leading researchers pass on

some of their legacy does, also. It’s a patriarchal-style

system, but women do participate in it.

Logical positivists or empiricists sometime argue that knowledge

can only come from experience. I liked to respond (back then)

that I had never seen an atom, but I believed in their existence.

And to this day I haven’t seen one. But the whole body of physical,

chemical, and biochemical knowledge holds together really well.

Maybe theories can only be disproved, but not proved. But when they

hold up for years without disproof (through evidence) they really

start to seem true.

Back in the 1970s molecular genetics was hot in the academic

world. A lot of people were working on research in the event

chains leading to protein synthesis (DNA transcription to RNA,

and RNA transcription into proteins, via the genetic code). The

scientific community referred to a “central dogma” when discussing

these events. So we might ask “do the scientists believe themselves?”

WIthout minimizing the harm that was done to the public by his “noble lie”, the thought occurs that Fauci had an accurate read on how the American public would have responded to an appeal to not hoard precious scarce PPE that was more urgently needed by the medical professionals…. the appeal would have been ignored by a sufficient fraction of the population to precipitate real problems for the “front-line” medical workers..(And there were major problems already, without the public competing for scarce protective gear).

The nation ran short of toilet paper for a while due to hoarding behavior; can it be imagined that PPE would not have been hoarded by the non-medical public?

A more current example might be the disregard of masking recommendations in some places, or the evident refusal of many college students to respect the safety regulations imposed by colleges hoping to safely resume residential instruction.

I don’t think that Dr. Fauci, given what I suspect he rightly had reason to believe about the American people, had much choice. There is scarcely any public spiritedness among the nation’s leaders, and not a whole lot among the public, either, it seems.

When the nation went into the pandemic without adequate stockpiles of PPE, the die was IMO already cast.

i agree. when the Noble Lie part came out, i considered what i would have done in that situation, and arrived at pretty much the place you describe. it was immediately important that ppe be reserved for those on the front lines.

no good answer, in a less than ideal situation.

i do not have the same sympathy for the gilead rent seeking that came later, though.

But the general population could have been wearing what they are wearing now, which take nothing away from PPE for medical workers: cloth masks.

> But the general population could have been wearing what they are wearing now, which take nothing away from PPE for medical workers: cloth masks.

The message was not “PPE for health care workers.”* The message was “Masks don’t work.” So a lkely knock-on effect would have been to impede grassroots “innovation” in mask design and manufacture.** And in a pandemic, which multiplies, days count.

NOTE * Which of course could have been made to work. Are there no public relations firms?

NOTE ** Perhaps the PMC mindset was “Only PMCs can do such things?”

I read an interview at some point that did point to another reason as well. The interviewer was some doctor or medical scientist. He advised public health officials, and he was extremely skeptical about diy masks.

The interviewer asked something along the lines of, why not try masks if the worst case is that it only helps a little.

And the guy said, that’s never the question that gets to my desk. It’s always a a quid-pro-quo. If people wear masks, can we allow more people in movie theatres. If they wear makes, can we fill up touring cars, trains, or bars, or offices, fitness centres, etc.

Basically, at the policy level masks are not advocated by people who worry about the virus, but mostly by trade organizations of businesses that are hit hard by some other anti-virus measure, and who want that other measure gone

I think this has made such people very defensive. Even when they think that masks have a positive effect, they cannot really quantify that effect or trade it against other measures. Especially if they don’t know how serious people will take the masks.

The thought occurs that there is a kind of “prisoner’s dilemma” character to this situation. If I hoard PPE, I benefit, but if everyone tries to, the society suffers, and me with it.

Or a “fallacy of composition”, in that what works at the micro level does not in aggregate.

In a sense, while Dr Fauci was wrong that “masks don’t work” at the micro level, in the American socio-political context at that moment in the pandemic, when masking might have been embraced as a substitute for other measures needed to slow community spread, he may have been quite right at the macro level that “masks (alone) won’t work”.

Yes. And the evidence of Fauci’s assessment of the response by some in the “public” was the cadre of grifters who bought warehouse fulls of PPE and expected to gouge healthcare workers (hospitals) for big profits.

I followed the pandemic outbreak in China and early on saw the “hoarding” of PPE supplies by American businessmen as they anticipated the need for these supplies. Squeezing Fauci on his masking equivocation ignores the wholly unprepared national governmental action of the Trump administration to deal with the novel coronavirus.

A fair bit of the issue though stems from trying to argue something on scientific or any other merits against another person/group to whom has desire or ability to discuss or accept a rational discussion.

When someone or some group doesn’t even engage in rational argument maintaining a complex nuanced set of debating points is unlikely to convince them nor the audience listening on.

Messages that are simple are often more easily digested and thus more persuasive than the nuanced reality.

Another great essay, Lambert. We lucky readers can only be grateful for your (and Yves’) good work.

[lambert blushes modestly]

My questions about Science are:

1. Who owns this particular Covid19 science? Big Pharma, many other corrupted institutions and the Government. The science is not there to benefit the average citizen.

2. The Science is only pursuing one solution to the problem. The available resources are not being invested into possible alternative solutions which are actually being suppressed. Is that really Science?

3. Many criminal organizations are involved in this vaccine development. I would love to see an article by a criminologist examining the criminal backgrounds of participants in these studies. Maybe even devote some resources to such an examination.

Yes, the Noble Lie. All those past Noble Lies to protect me, to keep me safe, to protect my country, to guarantee my future…….And when you lie, the onus is on you, it is not on me.

There is a lot of socio-psycho science that keeps those Noble Lies coming.

Thanks for this Lambert, you’ve expressed my own reservations about the use and abuse of ‘science’ far better than I could.

I think that when all the dust is settled there needs to be a fundamental reappraisal of public health science. The reality is that for all the amazing work done by individuals and some national and regional organisations, there have been widespread and fundamental failings in the scientific process, at multiple levels in many countries (and of course WHO). I think a key issue is that there isn’t really such a thing as ‘public health science’, instead we have multiple specialities covering all aspects of a pandemic, with a lot of random luck as to whether the individuals tasked with pulling all the information available together were capable of doing so without exposing their own bias or prejudices.

You have to ask some pretty hard questions when fringe individual scientists on Youtube, such as Dr. John Campbell or Dr. Chris Martenson were calling things correctly on key issues like travel restrictions, masks, and immune system boosting, many months before public bodies and the mainstream medical establishment caught up. Of course, many still haven’t – I find it amazing that there is still pushback by some against mask wearing and taking vitamin supplements.

Another important issue I think is that even the best scientists are fond of falling back on a fairly simplistic scientism when faced with challenge. Its remarkable how many scientists aren’t often aware of the vast literature on bias and scientific failure, possibly because some of it is tainted by association with the extremes of cultural theory and sociology. Far too many scientists seemed unable to step outside their own narrow epistemology (or paradigm if you prefer) to apply findings from a wide variety of disciplines to real world applications. And this is before we even begin to look at the malign influence of money and big Pharma and individual egos and internal politics.

There are additional problems between hard and soft science (hard defined as that a statement in that science can be proven correct or not by independent repeatable experiment).

Given that even in hard science you can get wrong results – famously, even in maths, the hardest “science” of them all you had proof which were wrong (Cauchy on some infinite series for example), for the soft sciences were often you cannot do well repeatable experiments with most of the externalities taken care of you have to have much higher suspectibility of any results. But unfortunately, physics envy is a real thing.

The Trouble with Physics by Lee Smolin is a great read, outlining how in even the very hardest of sciences, things can go badly astray.

Oh, absolutely.

The whole string theory has absolutely no new testable predictions (at least when I last looked at it, which arguably is a while, it didn’t. All the ones they claimed were either shown not needing string theory or wrong IIRC). So as a friend of mine said “intelectual masturbation”, and that seems to attract all sorts of people.

This strikes me as slightly unfair.

“Internal consistency” is an important criterion for a fundamental theory of matter and its interactions.

We know that consensus Physics as it currently stands, General Relativity for gravity and the elaboration of Quantum Field Theory for all other interactions (resulting in the somewhat baroque Standard Model of particle physics), is not internally consistent because GR is a non-quantized theory.

The fundamental motive behind the development of String Theory was to find a quantizable Theory of Gravity. It turned out that this was not possible in fewer than 11 dimensions.

I have no idea whether String Theory is a true account of microphysics, but I don’t think that it can’t be facilely dismissed as mental masturbation. If gravity can be quantized within the context of String Theory, that strikes me as a significant achievement.

—

It may be unfortunate that the elaboration of string theory has led where it has, in terms of “the landscape” of essentially infinite possible variations on low energy physics, but I’m not sure that’s a reason to reject string theory per se. Maybe the world really is like this. And maybe it isn’t.

I remain impressed with the prospect of the quantization of gravity.

A theory that makes no new (testable) predictions has little value.

If someone comes with a quantization of gravity, I’d expect it to have a testable predictions, otherwise it’s just restating the same. Maybe more efficiently, maybe not – but it’s not really new.

Given how much effort went into ST, one would expect more out of it than just restatement of the existing. IIRC, for the “beautiful” (i.e. simple) ST, it wasn’t even restatement, it made measurably wrong predictions.

Actually, there is at least one testable implication of string theory — since gravitons are not confined to the 4-D subspace within the 11+ D world that the theory hypothesizes, at distances shorter than the compactification radius of the additional dimensions, gravity would depart from the inverse r-squared law (it would weaken with distance faster than 1/r^2).

If the compactification radius of at least one of the additional dimensions is large enough to be detected in laboratory experiments, this would provide evidence for the existence of the additional dimensions.

There has been considerable effort to search for such departures. Gravity being such a weak force at laboratory scales, the experiments are quite difficult.

Here’s a recent report, with a null result down to about .03 mm scales.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42254-020-0168-6

I would say “not true” to the “no testable consequences” assertion, though I concede that the laboratory evidence to date has failed to detect evidence of this feature of string theory.

But there is at least one feature of String Theory that in principle is amenable to experimental verification.

Out of curiosity, I poked around a little to try to get sense of the current assessment of the state of String Theory.

It appears that there are numerous useful spinoffs of the mathematics that had to be developed to reduce the concept to a formal mathematical description. I think that “useless” is too pessimistic an assessement though it is certainly true that the original aim of the discipline has not been fulfilled and is currently still far from fulfillment.

https://www.quantamagazine.org/string-theorys-strange-second-life-20160915

I studied physics at an earlier phase of life, and never made it past a class on the preliminaries necessary for the quantum theory of fields. I did get through an intro graduate class in GR.

Something that is clear to me is that each advance in the mathematical description of nature has required a more complex set of mathematical tools, and a larger research effort in terms of number of people thinking about the problem.

Maybe there is no final theory, or maybe the final theory is not comprehensible to human minds.

But I don’t see ST as wasted effort.

Well, given that ST is more than a half century old, and especially in 90s and 00s a lot of effort in the world of physics went into it, I’d expect it to turn out some stuff that would be usefull even if not at all related to ST itself.

But really, for the amount of effort, and, worse, supression of most of others competing efforts, I still consider it a massive waste. I may well turn out to be wrong, even very shortly. One never knows – heavier than air flight was “proved” to be impossible. But on the past performance I’d put it there with aurum potabile at the moment – lots of effort with useful (and some even spectacular) side inventions, but fundamentally waste.

Well, there are actually two problems here.

One is that we all do trust science, implicitly. Because we use cars, everyone who reads this is using electronic device of some sort, we walk/drive on bridges and enter buildings. All of which is build on science.

There’s a massive body of science (theoretical and applied aka engineering) that if we “didn’t trust” we’d go back to stone age.

And, *gasp* some of that scienec is actually wrong – like all the Newtonian science. Except in a lot of cases it doesn’t matter, because it’s a good enough approximation – and most of people who use it know it’s an approximation, so won’t try to build GPS-like systems on Newtonian physics or electronics on Ohm’s law (and similar) only.

Although recently even those come under to “we don’t trust it”, cf the 5G idiocy.

Also, for most of us, it’s actually close to impossible to take that science on w/o trusting it implicitly, because a proper grounding in quantum mechanics (say) is not something that you can get by reading a book in an afternoon.

So, overall, most of us do trust the science, especially well settled one, but even a relatively recent one which often may look more like magic than something we’d really understand. And, TBH, we don’t really have much choice in some of the parts – citizen science is all well and good, but you can’t do high-energy physics as a citizen science easily, nor can you do molecular biology (safely).

The larger problem is “do we trust the scientists”? Which, as Lambert says, is way different from “do we trust science”.

And that’s IMO the crucial question, because what we can be told by humans may, or may not be science, and that’s may be hard to tell – which leads to the “trust the science” bit IMO, but for different reasons.

And when we run into the human factor, it gets very very complicated.

– even when we have good science, getting it across matters (i.e. good teachers)

– even good science may need “lies to children”, i.e. simplifications (for example we teach children Newtonian physics as if it was absolutely true) that can cause confusion.

– even good science may have unanswered questions where we do not have good answers (for multitude reasons) which cause confusion

– even good science can be misused (science is not morally good or bad)

– even people who are good scientists in their fields can badly misunderstand science even in a pretty close fields where they _think_ they could know, but don’t;

– and a whole host of bad science/bad actors problems.

Science is a tool, and as any tool it can be operated well or badly. We’d not be saying “trust the tool” – or not, we’d be looking at the wielders + history of results.

Although with the view of existence of Flat Earthers, there’s a limit on what level of trust can be ever achieved.

Quebec’s The Suburban link does not work.

To state the obvious, there is Science, as a body of hopefully coherent and reliable knowledge, there’s Science as an activity practised every day, and then there are Scientists, who are supposed to do the practising. Ideally, scientists should be doing Science in a scientific manner. But we all know that’s not always the case – you only have to look at sites like Retraction Watch to see how much incompetence and dishonesty there is in the actual profession. It’s not necessarily true that scientists are using “Science” either: one of the big discoveries of the last 10-15 years is that a lot of traditional nutrition advice – calories, carbohydrates, fats, grains etc – isn’t based on “Science” at all, but has the status of academic folklore. Once rigorously tested, it all started falling apart.

So the issue is not “Science” as such, but whether you trust scientists, individually and collectively. Few of us are actually competent to weigh and measure advice by scientists and make up our own minds. So in the end, we fall back on our prejudices, and we take seriously scientists whose conclusions comfort our beliefs, telling ourselves that “it’s science”, so that must be all right. In the circumstances, if you have refused statins, because you read about the dangers, if you have changed your diet to High Fat/Low carbs with good results, if you have tried a therapy (acupuncture, perhaps) dismissed by the scientific establishment and found it works, then there’s a reasonable chance that you’ll think the Covid menace is a scam, or at least overhyped, because it’s just scientists doing what they always do. A lot of writing on this subject seems to assume that there is a magical way of distinguishing between scientists giving good advice and those giving bad advice. If the same scientists who told you to take statins tell you to wear a mask, why should you believe them? I don’t think there’s an answer to that.

Mostly agree.

I have one disagreement point – I’ll put more trust into scientists that had publicly declared they were wrong on their own, and backed out their statements than any other. Not because they are more likely to be right, but because I believe (not having any other information) that someone who publicly admits being wrong is more likely practicing science as method than something else, so I can at least expect to find out they were wrong.

Aye. Public admission of being wrong.

that’s an important quality for anyone to have, in my opinion.

i figure the money has screwed up science quite a bit…but there’s also plain old human nature.

we’re pack animals unless forced to use our own wits.

under “money”, i include the click-seeking that so much of the “media” and pseudomedia have fallen for.

some person at a website peruses the journals for click bait(“statistical correlation between eating the crust of bread and cancer”=>”bread crust causes cancer!!!!”)…and rush the juicy bits to their feed to generate clicks(and my brother’s wife forever after insists on him buying only crustless bread(!)).

the damage is cumulative.

Wait, important question. What the heck is crustless bread? Raw dough?

David, how about the so-called new soup and shake diet. My partner went ape when this first came on the news. It is complete bullshit. And, as we unfortunately have come to expect, the idiots running the government are supporting this faddish crap.

Agree with both you and vlade about science and its practice. My recommendation for those who don’t know much about science would be to read some accessible history of science. There is a good bit that can be easily found.

I wasn’t recommending any particular diet, just pointing out the uncomfortable truth that most traditional nutritional advice isn’t based on any science at all. Some of it seems to be magical thinking: “eating fat makes you fat”. Why? Well, it’s sort of logical isn’t it?

I realized that. I wasn’t suggesting you recommended it. Another piece of nutritional rubbish — cholesterol. Just being given your total cholesterol in a number tells you virtually nothing usable at all. There is ‘good’ colesterol and ‘bad’ cholesterol – and they both contribute to your total cholesterol score. So, you need your lipid scores (HDLs and LDLs) and the level of your triglycerides for you to ‘know’ where you lie in the cholesterol stakes. And this information should be collected once or twice a year, depending on your doctor’s advice.

Science, like any kind of human paradigm that requires some level of faith and trust in order to function as a shared belief system, is just as susceptible to dogmatic exploitation as any other discipline. Considering that science is a method of investigating the world, its inherent self-challenge ideology helps make it more resistant to false fact propagation.

Still, it reminds me of the South Park episode where Cartman gets frozen waiting for a Nintendo Wii and arrives in a future where science has become a religion. The episode, while a goofy satire of Buck Rogers, still rings true enough about how dogmatic trust can be twisted into something unhealthy.

Science never ends because knowledge is infinite. To know the infinite is to become “God”. So how is science quest that far off from the religious quest? It is a search for certainty in an unpredictable world. So I can trust God or trust science. But science is made by man, so I will trust God. No, not some dude with a long beard in a cloud. I mean I trust the nature of existence without having to understand it.

The only reason we need so much science is that we have become so dependent on it. Science is the original sin and the Christian would say, or for the Daoist, the Ten Thousand Things.

I can use science, but it is not something I would ever trust.

You trust some sciences every day, depending on the source and context. If an engineer says a bridge is safe and you know that this engineer knows about such things as bridges, and you know that lots of bridges have been stable, you trust the judgement. But if this engineer builds cars, you might not take his/her word about the bridge since there may be no scientific underpinning, practical or theoretical, of what is being said about the bridge. In other words, they may not know what they are talking about with respect to this particular case. But, if this engineer is a good car engineer, you might trust what is said about the relative safety of various makes of car.

If the engineer never built the bridge I do not have to worry about trusting anyone.

And how do I know I can trust an engineer anyway? Do I also need to get a degree in engineering?

My only goal now is to limit the science in my life so there is less science I need to trust.

Hi Lambert, I can’t find the reference for note 3, Thomas Frank’s comments on the this whole issue. Would you post that? Thanks.

Science is a process

Hypotheses

Thesis

Antithesis

Proof

There is no “belief” because understanding evolves. There are some “settled” theories, but they are continually tested.

If you want ‘belief” that’s a religious dogma. Go join a Church.

damn, i was literally going to say the exact same thing.

Only thing that I’d add is that a good scientist makes public their data for others to scrutinize. And any scientist calling their data “proprietary” raises some big red flags—regardless of any politics.

Jacob Bronowski on absolute certainty v. knowledge https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXsVKbHY_T0

Trust the … Science … scientists … expert opinion … experts … all attempt to justify arguments made ad verecundiam. An argument should stand on its own merits and the merits of the warrants used to support it. Scientists, or experts, can advise how to accomplish certain goals, but they cannot and should not decide what goals to accomplish. Political policy questions lie outside the realm of Science. Scientists and engineers can design a bomb that will destroy a city. But the decision to build that bomb is a political decision. The decision to use that bomb to destroy a city is a political decision.

Science can identify and characterize a problem like changes in the amount of the Sun’s energy retained in Earth’s climate systems as a result of adding CO2 to the Earth’s atmosphere. Science can estimate the amount and likely consequences of that additional energy. Science can demonstrate how human activities are responsible for adding the CO2 to the atmosphere. But Science cannot decide what should be done to address the amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere by human activities, or what should be done to address the consequences of the additional energy driving the Earth’s climate systems. Those are political issues.