Yves here. Corruption has become so pervasive in the US that we tend to think of it as driven by money considerations (career advancement is one manifestation). This study of scientists who’ve become so enamored by their supposed discoveries that they resort to destructive conduct doesn’t mesh tidily with our contemporary notions of unscrupulousness. The abusers profiled in The Icepick Surgeon are more hubristic….maybe even meglomaniacal…entranced by their own distorted vision of conquest. They aren’t included in this book, The Icepick Surgeon, but it isn’t a stretch to think that the doctors that devised America’s enhanced interrogation techniques, as in torture, are cut from similar psychological cloth.

By Elizabeth Svoboda, a science writer based in San Jose, California. Her most recent book for children is “The Life Heroic.” Originally published in Undark

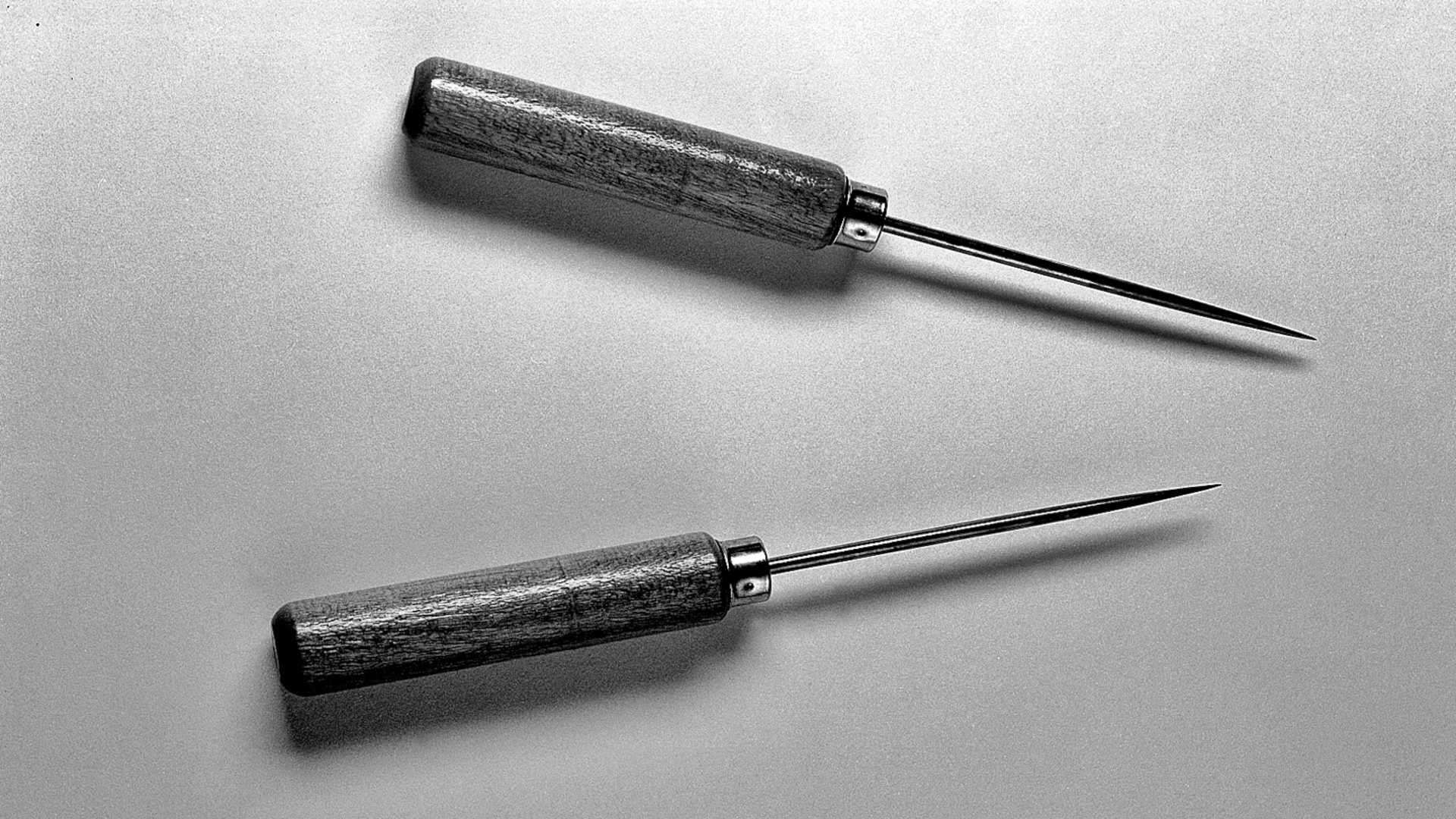

L0026980 Watts-Freeman lobotomy instruments.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Walter Freeman itching for a shortcut. Since the 1930s, the Washington, D.C. neurologist had been drilling through the skulls of psychiatric patients to scoop out brain chunks in the hopes of calming their mental torment. But Freeman decided he wanted something simpler than a bone drill — he wanted a rod-like implement that could pass directly through the eye socket to penetrate the brain. He’d then swirl the rod around to scramble the patient’s frontal lobes, the brain regions that control higher-level thinking and judgment.

Rummaging in his kitchen drawer, Freeman found the perfect tool: a sharp pick of the sort used to shear ice from large blocks. He knew his close colleague, surgeon James Watts, wouldn’t sanction his new approach, so he closed the office door and did his “ice-pick lobotomies” — more formally, transorbital lobotomies — without Watts’ knowledge.

Though the amoral scientist has been a familiar trope since Victor Frankenstein, we seldom consider what sets these technicians on the path to iniquity. Journalist Sam Kean’s “The Icepick Surgeon: Murder, Fraud, Sabotage, Piracy, and Other Dastardly Deeds Perpetrated in the Name of Science,” helps fill that void, describing how dozens of promising scientists broke bad throughout history — and arguing that the better we understand their moral decay, the more prepared we’ll be to quash the next Freeman. “Understanding what good and evil look like in science — and the path from one to the other — is more vital than ever,” Kean writes. “Science has its own sins to answer for.”

Expert at spinning historical science yarns — his last book, “The Bastard Brigade,” was about the failed Nazi atom bomb — Kean presents a scientific rogues’ gallery that’s both entertaining and chilling. Naturalist William Dampier, who influenced Charles Darwin’s work, resorted to piracy to fund his fieldwork in the 17th century. He joined a band of buccaneers that seized gems, scads of valuable silk, and stocks of perfume in raids throughout Central and South America.

A century later, celebrated Scottish surgeon John Hunter worked with grave robbers to obtain bodies so he could study human anatomy. His colleagues emulated his approach, and the pipeline from corpse-snatchers to anatomists continued for decades. The practice was tacitly accepted because it could yield valuable insights — Hunter discovered the tear ducts and the olfactory nerve, among other things — but the human toll was horrifying nonetheless. At public hangings, so-called sack-‘em-up men “sometimes even yanked people off the gibbet who weren’t quite dead yet,” Kean writes. “They’d merely passed out from lack of air — only to pop awake later on the dissection table.”

In a way, though, the gruesome endpoints Kean describes — the scrambled brains, the ransacked ships, the deathbeds — are the least interesting part of his story. They mostly confirm philosopher Simone Weil’s impression that real-world evil is “gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.”

What’s more compelling is Kean’s take on how the scientists justified their actions. They pushed aside thoughts of collateral damage — the lives they disrespected and damaged — by rationalizing that their contributions outweighed any harm they were doing. Freeman’s work at an early 20th-century psychiatric asylum convinced him of the unalloyed good of calming agitated patients via lobotomy. “The ward could be brightened when curtains and flowerpots were no longer in danger of being used as weapons,” Freeman observed.

But it wasn’t long before the downsides of Freeman’s blinkered strategy showed up. Botched lobotomies killed some patients, while others, like John F. Kennedy’s sister Rosemary Kennedy, emerged unable to speak normally or care for themselves.

Kean excels at conveying each scientist’s slide into corruption — one so gradual that, like the fabled boiling frog, they scarcely noticed they were in hot water. Freeman was once a wunderkind neurology professor, beloved by his students. At some point, he opened a book by Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz and got religion. Moniz claimed excising brain tissue helped end-stage patients recover enough to leave asylums, and Freeman felt inspired to help his own severely ill patients in the same way. At first, it seemed like a reasonable approach of last resort. In Moniz’s midcentury heyday, lobotomies became an accepted part of medical practice at asylums, and Moniz even won the Nobel Prize in 1949 for his advances in psychosurgery.

But then Freeman started performing more and more lobotomies, with fewer ethical misgivings. He increasingly used the crude ice pick to probe patients’ brains, rather than Moniz’s more traditional surgical tools. And he started offering the surgery to adult patients with less severe mental illness and, finally, to young children with mood disturbances. Why not operate as early as possible, he argued, before things had a chance to get out of control?

English naturalist Henry Smeathman likewise began with the highest intentions — he was an ardent opponent of the slave trade. But years later, on a lonely posting to Sierra Leone, he yukked it up with slave ship captains in his free time, then signed on as a slave-trading agent himself. His rationale? By putting his oar in, he could ensure his field specimens got fast passage on slave ships from Africa to England. “Preserving dead bugs and plants meant more to him than preserving his morals,” Kean notes

Kean’s catalogue of scientific ne’er-do-wells does have some notable gaps. While he briefly mentions Nazi doctors and their horrifying experiments on concentration-camp prisoners, he skips entirely over early 20th-century U.S. eugenics, a branch of pseudoscience concerned with preserving “fit” human bloodlines and discarding the “unfit.” Founders of this movement, including researcher Francis Galton, in many ways prepared the ground for the genocidal crimes of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen.

Yet Kean makes up for his omissions, at least in part, with the complexity of the portraits he does include. We learn about Smeathman’s respect for his Sierra Leonean guides’ natural history knowledge, and about how carefully Freeman followed up with each of his patients to document their progress. Many unscrupulous scientists, Kean reveals, are far more like us than not. Though it’s comforting to view them as alien, we have many of the same human tendencies they do — and, like them, we have a hard time detecting when the drip-drip-drip of moral compromise turns into a flood.

“Any one of us might have fallen into similar traps,” Kean writes. “Honestly admitting this is the best vigilance we have.”

To avoid such traps, Kean advises scientists to adopt clear ethical guidelines before launching any project, based on research showing that people behave more ethically when they assert their honesty at the start of a task. He also advocates for a technique developed by psychologist Gary Klein and championed by Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman called the premortem — thorough assessments of all the ways a planned research venture could go awry. But the book stops short of specific policy implications on this score; there’s no analysis of how well scientific premortems might work to forestall future dastardly deeds.

What’s more, some scientists are already so far into the morass that premortems are out of the question. It’s fitting that Freeman’s final surgery, an early 1967 lobotomy, ended in disaster. He failed to aim his pick just right, and the patient sustained a brain bleed and died. No doctor in the U.S. has performed a transorbital lobotomy since — at least, so far as the medical record shows — but lobotomies in general continued into the 1970s. It may be true that, thanks to Freeman’s surgeries, some patients left asylums and returned to their families. But decades later, what is remembered most are the lives the ice pick destroyed.

UPDATE: This piece has been updated to clarify that while the medical literature shows that transorbital lobotomies ended in 1967, lobotomies in general continued into the 1970s.

Great article. Thanks! While not my area of expertise at all I’ve got a fascination with the troubled evolution of our mental health system and the science used within it. One book I have read and re-read is “Women of the Asylum” which offer firsthand accounts of women institutionalized from 1840 through 1950. It’s broken up into sections of approximately 25 year increments with historical analysis given between each section. It’s fascinating to read about how the horrors perpetuated were seen at the time as more humane advancements (and often were much better than the prior eras). From poor houses which were absolute horrors (yet better than starving in the streets) to asylums which offered some care for the afflicted yet were rampant with bad science and abuse, to the more modern institutions which still tended to be used to punish as much as help and heal.

As one woman said, “if you weren’t crazy when you got here you will be when you leave.”

There was one account from a woman who was lobotomized. Honestly, it was one of the less horrifying stories in the book. The ice baths, force feedings so brutal teeth were knocked out, injections of nasty rudimentary drugs, etc would make me opt for the lobotomy if that would make all the other stuff stop.

That Freeman turned his mobile lobotomy operation into a spectator sport (his vehicle was referred to at The Lobotomobile) fits with how the asylums would hold weekend “events” where townspeople would visit, have picnics, and watch as the “deranged” were paraded around for their entertainment.

Anyway, I highly recommend the book to anyone and everyone. It’s a fascinating read and the firsthand accounts really make it compelling and harrowing.

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/44099.Women_of_the_Asylum

Also, with all the news lately about the discovery of mass graves at Indigenous schools, it might be of interest to some here to read this amazing blog collecting the history of the Cantor Asylum for Indians. Some truly dark stuff but an important history that is basically forgotten (or just ignored).

http://cantonasylumforinsaneindians.com/history_blog/

As one woman said, “if you weren’t crazy when you got here you will be when you leave.”

Likewise with homelessness? It really offends me when people say homelessness is just a result of mental illness or drug/alcohol abuse when being homeless itself is extremely stressful and unnatural.

The rich man’s wealth is his fortress, the ruin of the poor is their poverty. Proverbs 10:15 [bold added]

Being both homeless and living with Bipolar Disorder I can say it is probably a mix of both. My decent into homelessness began when I could not work anymore because of my Mood Disorder. And my health certainly much more difficult to manage with the added stress of being homeless.

And a note: They are still doing these evil experiments on people, but instead of ice picks, now it is done with the over use of medications that are not even close to cures. I was just helping a friend cope as she got her off SEVEN medications that were added on over 15 years for what turned out to actually be a horrible B6 deficiency. Real-world evil is “gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.” They just were adding medications to treat the side effects of other meds that were not working in the first place.

While I was living in Pittsburgh, I was friends with a man who was a psychiatrist for the VA.

One day, he was doing a consult on a patient, who, shall we say, had a bit of temper. Dr. Ed learned about it as soon as he stepped into the patient’s room. Patient threw a pitcher of ice water, and it barely missed Dr. Ed’s head.

Dr. Ed diagnosed a severe Vitamin B deficiency and ordered immediate treatment.

Several weeks later, Dr. Ed was in his office and there was a man at the door. The man asked if he was Dr. Ed.

“Yes.”

Dr. Ed couldn’t place the guy, and he was more than a little bit concerned. I mean, when a stranger shows up at your office door, and you’re a psychiatrist, the story may not have a happy ending. But this story did.

The man explained who he was — the ice water pitcher thrower — and he offered profuse thanks to Dr. Ed. The Vitamin B treatment had worked, and the patient was extremely grateful.

Science and Technology are becoming more and more powerful every day. And there is more and more of it. Think gene splitter in your neighbor’s apartment.

What are the ethical/psychological qualifications to be a scientist? To my knowledge, there are none.

What percentage of the population is sociopathic or psychopathic? The rate of sociopathy is about 5% of the general population and psychopathy about 1%. Some think these rates are much higher and are skewed to more rich and powerful people.

It would seem then that the above facts are a recipe for disaster that is, more and more powerful Science, available to more and more crazy people. Yet, all is seemingly well in Science. No navel gazing there. All Science is good, proceed. Think Fauci and Gain of Function.

One area that I think we can see all around us is Behavioural Science. Even NIH has admitted using shame and other emotions to get the Covid compliance they want. An army of well compensated Behavioural Sciencists is on the march after the Covid dissidents. The dawn of TV, and even before it, created a huge demand on methods to manipulate the human mind and behaviour. Much of this financed in academia by Government.

I have listened to a book by a famous and esteemed Behavioural Scientist and in the book he describes all the mind manipulating techniques that can be used. Never once did he express any misgivings about the proliferation of such knowledge or who might use it.

So, I do not trust Science, I distrust it more and more with each passing day.

Humans have a tremendous capacity for self justifying our own interests and obsessions. If you add in the element of adulation that top doctors/surgeons/scientists can get, its a pretty toxic brew. In large and small ways I doubt if many of us can be excluded from this tendency. Of course, sometimes its a positive – ruthless obsessives can drive science and medicine forward.

The trick in any school of endeavour is to have rules that stop the worst things happening, without putting too many limits on gifted mavericks. I’m not sure anyone has ever gotten this balance entirely right.

I’ve just seen this on Twitter from Christina Pagel on research indicating that Covid can result in long term cognitive impairments.

If this is true – and of course its just one paper, we don’t really know how serious this is – I wonder how people will see the many doctors and scientists who advocated letting Covid loose on the population – or even encouraged it (for example, those ‘experiments’ in England on allowing club nights) will be seen if we end up with a substantial proportion of our population with some degree of cognitive impairment.

One of my closest colleagues at NYU had Covid a year ago and still has cognitive impairment. (He’s in his 80s) And is unable to finish his book. Much lack of energy also.

So this can be a really frightening problem.

Just finished a Youtube by Dr. John Campbell, Important Long Covid Information, a discussion with two women who are advocates for long covid recognition, research, and hopefully, treatment. Much, much information here. Video is over an hour, took me three days to get through it. The reported symptoms are varied and not easily assignable to Covid. The most common, fatigue, ‘brain fog’, and anxiety, are difficult to quantify especially during lockdown conditions. Medical facilities are already triaging for acute cases by using an approved list of symptoms, which often do not even include the predominant symptom of the latest variant, and so testing is not available for these seemingly mild cases. Many countries do not even recognize such a thing a long covid; Canada and the US do not, so disability benefits not available. I myself believe I have long covid, but since I do not have enough of the approved symptoms to be tested my choice is to shell out $200 to see if I have something that they can’t/won’t treat anyway. For the Dutch woman, aged 23, her original infection was not only asymptomatic but also before the first case of Covid was reported in her Holland. Two years later she still has profound fatigue and a persistent skin rash.

We are a long way from being out of the woods on this, and the way ‘science’ is being perverted and stymied, I am afraid it will much darker before it gets lighter.

This thing is going to be with us for a long, long time, we will need science, real science, to get out of it, not messaging.

this study failed to adjust for confounders? Like HTN?

And that she is already trying to distance herself from posting it?https://twitter.com/chrischirp/status/1418934426172628992

Walter Freeman. Republican.

well that pretty much settles it then…

from links. an observation by our gracious host…

The only wonder is that it has taken our professional classes so long to see that a problem exists, longer to find someone to blame other than themselves, and longer still to struggle through to the concept that the problem might be more than [makes warding sign] Republicans,

Yeah, this is all pretty bad but it is only small beer when compared to what happens when some of these doctors go to work for the government. There they can scale up their work to whole populations. Here is a page talking about some of the stuff that they have done and some of it defies belief-

https://original.antiwar.com/jwhitehead/2020/04/27/the-us-governments-secret-history-of-grisly-experiments/

And I use to think that Project Paperclip was just about rocket scientists.

Yesterday morning, I heard a Zoom presentation by a man who used to co-own a business here in Tucson. He now lives in Costa Rica.

During his presentation, he mentioned that he attempted suicide late last year. He is in treatment right now, and part of it has consisted of a traditional ceremony involving the use of some hallucinogen that is used in Costa Rica. Sorry, I don’t remember the name.

Anyway, he’s doing a lot better these days, and he’s quite grateful for the care and concern he has experienced in Costa Rica.

Could it be ayahuasca?

my first thought too

Yup, that’s the stuff. And I just exchanged emails with this same fellow. We’re both into making mead, so we have quite a bit to talk about.

Methinks that just having other people to engage with will be huge for this guy. Best therapy going, IMHO.

The U.S. has a history of snake oil salesmen, some of them with Ph.D.’s. Some other examples include exposing U.S. soldiers and the public to fallout from atom bomb tests, testing drugs on prisoner, testing chemical weapons on soldiers, testing bio-weapons on U.S. cities, and using U.S. soldiers to determine safety limits for scuba diving.

For The Greater Good.

This Time It’s Different.

When you encounter people spouting the above, it’s time to run the other way.

when safe, I recommend a visit to a medical museum if you happen to have one nearby. They’re invariably fascinating. I’ve mentioned the Flaubert one in Rouen in comments before. The one time I was in Chicago I went to one there.

When I lived in London in about 2012 I went to the Wellcome gallery which had an exhibition on the human brain (probably my favourite piece was a sculpture of the capillary system of the brain, formed after having been injected with a kind of plastic dye). One part of the exhibition was pretty dark and had an effect on me that has stuck with me since. It was going into detail on some of the egregious experiments done by Nazis on the brain (sometimes in vivisection iirc), as mentioned in this article. I usually have a pretty thick skin for this sort of thing but at some point after reading about them and taking in all the abject information, I got an acute headache of a sort that I haven’t had before or since and had to sit down (I don’t often get headaches).

Thank you for the article.

Where I work all scientists and staff are required to take annual ethics training. But a scientist’s morals cannot be taught imo.

PBS has a marvelous series on Mental Illness. It can be accessed online

It shows just how crazy the history of this topic really is and how little is known.

The third episode discusses the lobotomy craze.

Electroshock therapy is another dubious “treatment” based on questionable research. As I recall, the person promoting this treatment had a financial incentive. One Flew Over the Coocoo’s Nest raised some of these issues.

I was struck by Rick Alverson’s 2018 movie, The Mountain, based (loosely or not) on the life of lobotomy pioneer Walter Freeman. Jeff Goldblum plays the Freeman-based character. Joe Friar in the Victoria, TX Advocate: “For a decade referred to as “The Fabulous 50s” it’s hard to find any glamour in Rick Alverson’s slice of American life..” Or in loved ones whose prestige would be irrecoverable so long as the mad woman in the attic could beard heard screaming every now & again. The age of the man in the grey flannel suit; America’s first decade as the greatest nation yet. To prove our lofty worth, to boast that the Free-World stars of humanity were ruling from our side of the Iron Curtain, to sign onto a Self-Actualization Movement that had no Ten Commandments, we needed the cunning to vanquish the demons of the fallible human soul. We went straight for the head. nyt review: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/movies/the-mountain-review.html

Does he mention Peter Breggins role in uncovering the ice pick treatments?

Breggin was my son’s psychiatrist for 6 disastrous months in 2010. He is a complete, incompetent quack. Our son had a psychotic break at the end of his second semester and was hospitalized for a week. We went to Breggin after reading several of his books, based on our fear of antipsychotics. He met with our son for 45 minutes, then pronounced him has having been upset and depressed about losing a girlfriend. Any parent would prefer that diagnosis instead of schizophrenia.

For 6 months we paid that monster $200 a week for his “therapy”. Cash only, if you can imagine (no records, no problems)! Schizophrenia, being what it is, unfortunately requires medication to manage the severe delusions and hallucinations. Back at school he had a second psychotic episode. We took him to Breggin’s office in December. He threw us out and did not provide any referral to another psychiatrist, only said to go to an ER.

It was a nightmarish experience.

Breggin makes huge sums being an “expert” witness against drug companies. He burnishes his credibility by claiming to treat serious psychiatric illness without medication. While drug companies deserve to be held accountable by regulation and litigation, somebody like Breggin isn’t the medical professional to do this.

Let it suffice to say, if our son had not been so traumatized by being thrown out of Breggin’s office resulting in a second 38 day hospitalization, I would have filed a formal complaint against his medical license and considered suing him for Malpractice.

In my opinion people like Breggin are only slightly better than Walter Freeman. He did tremendous harm, and the PTSD our son suffered remains 11 years later, compounding his schizophrenia. Competent medical care after the first psychotic break would have made a significant difference.

Very sorry to hear of your sons experience. That must have been horrendous.

Breggin did play a major role in calling out lobotomy and bringing an end to a very inhumane treatment.