Yves here. It’s useful to see economists starting to put pen to paper (or more accurately, creating models) to estimate how much damage Covid has done to growth, although some readers point out that less growth is to be keenly desired given climate change.

However, it’s also a bit perplexing to see the tacit assumption that we’re far enough past the worst of Covid to make estimates with confidence. As we’ve pointed out repeatedly, if hospitals reach the breaking point (as in someone run over by a car or suffering from a heart attack can’t get treated in a nearby ER), we’re going to see lockdowns. Their capacity has already shrunk due to doctors and nurses resigning due to burnout and/or reluctance to keep taking health risks.

By Luke Bartholomew, Senior Economist, Aberdeen Standard Investments and Paul Diggle, Deputy Chief Economist, Aberdeen Standard Investments. Originally published at VoxEU

As the global economy recovers from the immediate economic impact of the Covid crisis, attention is increasingly turning to the long-run impact of the shock on productivity. This column identifies several channels – including labour market hysteresis, impaired skill acquisition, belief scarring, an increase in zombie companies, and policy errors – through which the lasting harm will outweigh any positive supply shocks caused by the pandemic. The authors estimate long-term output losses in the order of 3% of global GDP. Scarring will be greater in some economies than others, pointing to the importance of policy in mediating and offsetting these channels.

As the global economy recovers from the immediate economic impact of the Covid crisis, attention is increasingly turning to the long-run impact of the shock on the productive potential of the economy. Such assessments are crucial in various looming policy choices. The UK government’s fiscal plans, for example, rest on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s assessment that the UK’s economic outlook will remain 3% below its pre-crisis trend into the long run (OBR 2021). And as the US Federal Reserve and other central banks begin to remove policy support, estimates of potential output and the output gap will be central to the assessment of inflation pressures.

While there is a growing literature studying the lasting impact that cyclical shocks can have on the supply side of the economy (Cerra et al. 2020), empirical work has tended to pick out financial crises as a source of shock with particularly lasting effects (Fuentes and Moder 2021). The Covid crisis is not a financial crisis, and past pandemics may not provide an especially helpful guide to the impact of Covid due to profound changes in the structure of the economy over time, and differences in the size and scope of pandemics (Bonam and Smădu 2021). There are therefore no ready analogues to consult when attempting to estimate the long run impact of this crisis.

In our recent work (Bartholomew and Diggle 2021), we approach the question by identifying the various channels through which this shock may cause lasting changes to the supply side of the economy, and assess how policy responses in various countries may have mitigated or exacerbated these channels.

A Positive Supply Shock?

Recent data are consistent with an increase in aggregate productivity since the onset of the crisis, but it is hard to believe this reflects a persistent improvement in the supply side of the economy rather than a compositional effect that will reverse in time as economies continue to reopen.

There are, however, a number of channels through which Covid could have caused persistent improvements in productivity. Behavioural studies suggest that path dependencies can lock agents into sup-optimal behaviour, which large shocks can correct by forcing re-optimisation (Larcom et al. 2017). Covid may have caused such a re-optimisation – around working from home, for example – and may have accelerated the adoption, commercialisation, and diffusion of existing technologies to allow for shifting patterns of production and consumption.

It is also possible that the development of mRNA vaccines will kick-start a wave of other innovations in life science and medicine that boost total factor productivity.

However, we think these effects are unlikely to outweigh the various channels through which we expect Covid to have permanently depressed the supply side of the economy.

Labour Market Hysteresis and Impaired Skill Acquisition

Economists have long understood that recessions can leave lasting scars on the labour market (Blanchard and Summers 1989). In particular, periods of unemployment are associated with skills erosion, loss of contact with the labour market, stigmatism, and a willingness to take unsuitable employment opportunities. All of these tend to weigh on labour supply and efficiency.

The impact of the initial Covid shock on labour markets around the world was mediated by differing labour market institutions in different economies. In the US, enhanced unemployment benefits allowed a surge in unemployment while supporting household incomes, whereas European furlough and short-time work schemes allowed a collapse in hours worked even as labour matches were largely maintained. These are in turn likely to mean quite different long run experiences: countries that experienced higher unemployment are more likely suffer from a lasting decline in labour force participation but may also enjoy a more efficient redeployment of labour.

The crisis is also likely to weigh more heavily on skill formation than standard recessions. The enormous number of education hours lost through school and university closures will have damaged human-capital accumulation (Burgess and Sievertsen 2020). While there is scope for catch-up learning among younger children, older children and adults on the cusp of entering the workplace may have permanently missed out on learning.

Indeed, it is well documented that downturns see a destruction of valuable firm-specific human capital (Fujita et al. 2020), and cohorts entering the labour market during a downturn tend to suffer lasting effects on their wages. The current cohort is particularly likely to struggle with building firm-specific human capital due to the weakness of the labour market combined with remote work making certain forms of firm-specific knowledge acquisition more difficult.

Belief Scarring

The experience of a large negative shock can have a persistent impact on the beliefs of firms and businesses. Such ‘belief scarring’ can cause individuals to take systematically less risk in their household finance and portfolio allocation decisions (Malmendier and Nagel 2009) and may be associated with persistently higher desired saving and lower desired investment, resulting in permanent economic damage (Kozlowski et al. 2020).

Household saving rates have increased significantly since the start of the crisis, although it is not yet clear how persistent this increase will prove in light of changes to government balance sheets (Bilbiie et al. 2021). It is also plausible that in those countries with more extensive policy support, belief updating will see households and firms take a more expansive view of how much state-provided income support will be available in future downturns, and reduce their saving accordingly.

Zombification

The crisis may also see an increase in ‘zombie firms’ – unprofitable firms with low stock market valuation and difficulty servicing debts. There seems to be a ratchet effect on the quantity of such firms, with their number increasing during downturns, but little evidence that this process goes into reverse during recoveries (Banerjee and Hoffman 2018). The rise in such firms may weigh on productivity through congestion effects, impairing the reallocation of capital towards more productive uses.

Given the various emergency support schemes provided by governments during the Covid shock – including cutting interest rates and easing financial conditions more generally, emergency liquidity facilities, and regulatory forbearance – this crisis may have created many more zombie firms. For example, the German Economic Institute in Cologne estimated that an extra 4,300 zombie firms existed because of the German government’s relaxation of bankruptcy laws (Röhl 2020).

On the whole, government support probably stopped many more otherwise viable firms from going bust during the initial collapse in demand following the outbreak of the pandemic than it kept zombie firms going. However, as the economy recovers and re-orients to shifts in production and consumption habits, it is important that resources are allowed to re-allocate and that policies encourage rather than impede this process.

Policy Error

The best way of ensuring this efficient reallocation of resources may be though expansive policy which tolerates periods of above-target inflation (Guerrieri et al. 2021). Indeed, we argue that insufficiently supportive demand-side policy is the biggest risk to the recovery from Covid and the mostly likely source of sustained damage to the supply side of the economy. Policy error of this kind was responsible for the sluggishness of economic growth following the financial crisis and it is easy to see similar mistakes being made again. There is also the risk that crisis fighting and economic weakness more generally leads to a reduction in impetus behind structural reform agendas, with trade liberalisation particularly vulnerable in this regard.

Quantifying the Damage

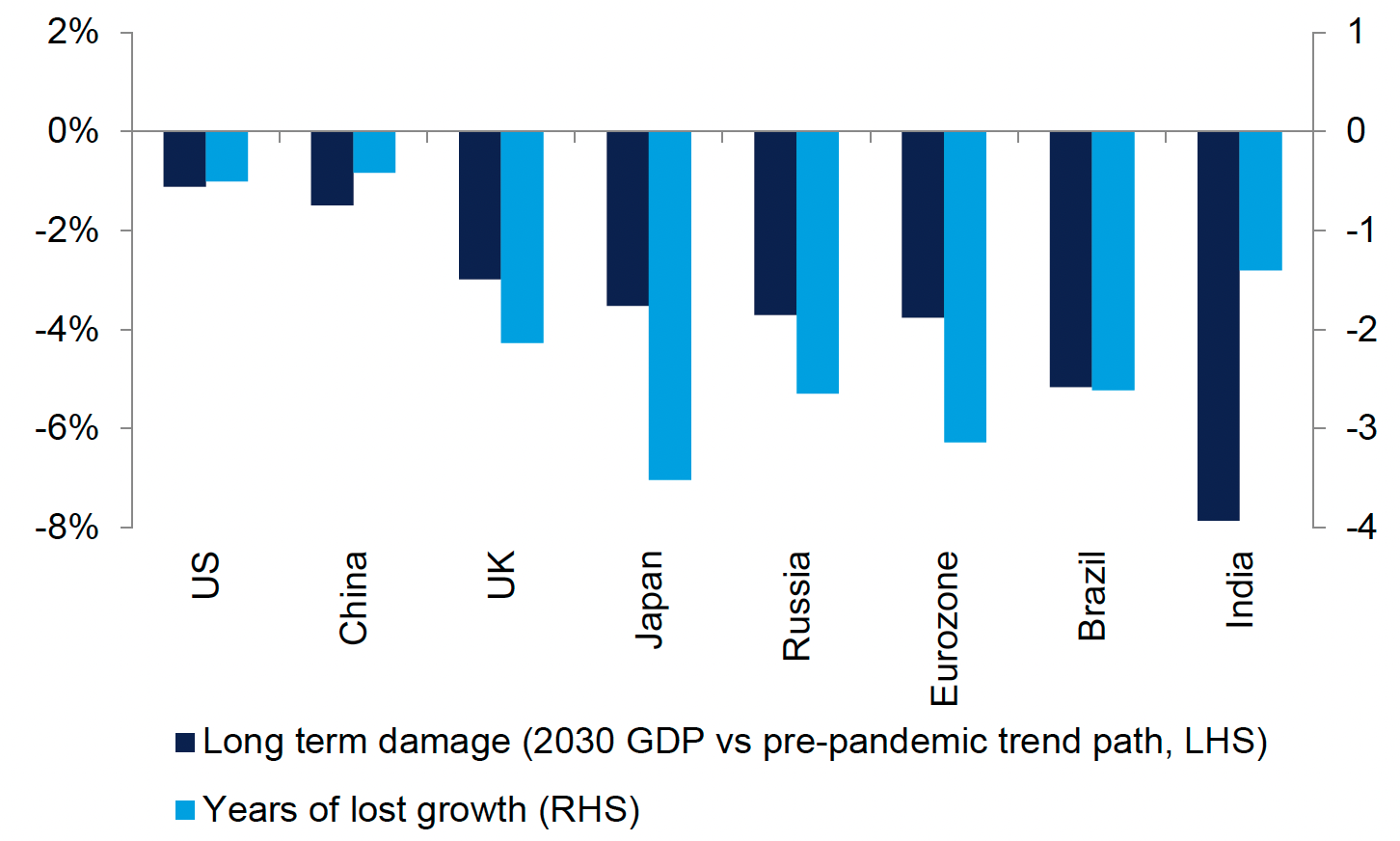

Bringing this together, our central estimate is that Covid will impart a permanent levels shock to post-pandemic global economic output of 3% of GDP. This is a third the size of the levels damage after the global financial crisis. There are sizeable cross-country differences in the degree of long-term damage, depending on the severity of the viral experience, the size and design of policy responses, and the structure of labour markets. This means more long-term damage to the path of GDP in the euro area, India, and Brazil, and less in China and the US.

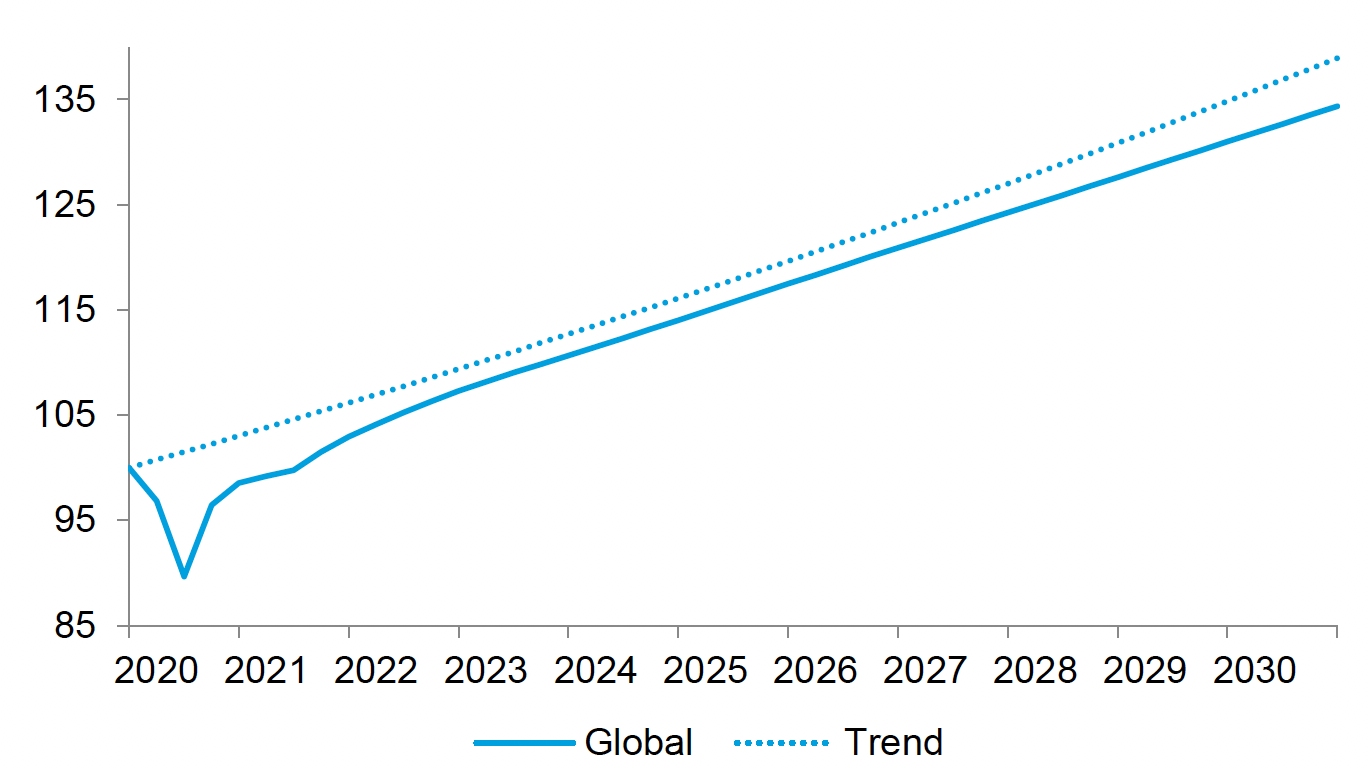

Figure 1 Path of global GDP

Figure 2 Long-term damage to level of GDP in 2025, relative to pre-pandemic trend path

Conclusion

These estimates are subject to very wide confidence intervals, not least because of the scope for policy to mitigate some of the channels we have identified. Indeed, the main takeaway of our analysis is the importance of pro-active demand and supply-side policies, ensuring a robust and rapid recovery in activity while allowing for any productivity-enhancing resource allocation to occur. We would stress investment in education catch-up, retraining schemes, infrastructure spending, demand management frameworks that require make-up of lost nominal activity, and a healthy competition regime.

See original post for references

Thanks. The flaws described here permeate through to other “areas” to become the received wisdom – that the worst is over, vaccination will “clean up the last of the mess” etc with no understanding that they are not sterilising vaccines so masks etc remain important.

I got attacked on a media channel for suggesting the YouTube owner might benefit from checking some sites NC put me onto. I was polite despite thinking his “new personal channel” at over 7 quid per month was madness compared to the “Big Hollywood streamers” but he’d have none of it.

Lots of “cinema/film” channels get into “culture wars” whilst ignoring the elephant in the room concerning basic cinema safety from delta variant. I guess if your entire business model is about to implode you don’t like the naysayers.

I’m pretty sure it will be years before we see the real results of Covid. Some might even be positive (higher wages for lower paid staff, for example).

There are a number of reasons to be pessimistic.

One is that I suspect that a very large number of businesses have bet big on ‘normality’ returning by 2022-23. You can see this already in ongoing investments in airlines and hotels etc. If a resurgence of Covid past the New Year stymies this, it could push a lot of companies over the edge, along with their creditors.

If Delta gets loose in China as it has already gotten loose in Vietnam it could have a huge impact on supply chains that are already under a lot of stress. Not to mention that a China under economic stress would hit commodity and luxury good exporters very hard.

Another ‘unknown’ is just how bad supply issues are in a multiplicity of supply chains. One contributer to the possible electricity crunch in Europe now is a lack of spare parts. We’ve already seen major problems in everything from cars to bikes. There is no reason to believe these couldn’t get worse rather than better, especially if there are any unforseen ‘other’ disruptions hitting the system. I’ve been idly wondering if one reason Biden went out of his way to talk down conflicts in the UN yesterday is that he’s been advised that the absolute last thing the world needs right now is additional disruptors.

Supply chains for bikes are still unbelievably bad. Some products are getting through so there are bikes in stores, but the retailers have to take a chance buying big lots of whatever they can get rather than getting a few bikes at a time that they know customers will buy.

I volunteer at a charity bike shop and buy certain types of parts, especially tires. I visit online retailers about twice a week. It’s like the stories about the old Soviet supermarkets, something I need will be in stock without any notice, then it will run out again in a day or two and not be available again for weeks or months.

My friends higher up the food chain say it’s even worse for a lot of manufacturers. They are booking production runs at Chinese factories five years out for bikes that haven’t even been designed yet. The odds that those production runs will happen as booked do not seem very high to me.

Yes, it must be very frustrating to be in the business, I know people here who have been waiting more than a year after ordering a bike.

Although I’ve been told of one small bike shop owner in England who was regularly teased by his friends for his habit of buying far too much stock and having boxed bikes piled up in his own home. He has had a very good year.

A few months ago the local Wal*Mart had around 4 or 5 kiddies bikes on display and that was it, but when I was there last week they were pretty much fully stocked.

For many items in short supply, the profound lack of computer chips is the culprit, but pushbikes don’t need any.

As a friend of mine is fond of saying, the only chips his bike needs are those he consumes with fish to fuel his rides.

Incidentally, those Walmart bikes are what is described in the industry as BSOs. ‘Bike Shaped Objects’ They come out of general fabrication factories in China and have the same relationship to real bikes as toy cars have to real cars. There are a lot of specialised manufactured parts in even fairly mundane ‘real’ bikes.

My brother retired last year from Quality Bike Parts (I think the largest such wholesale distributor in the US) after working there for decades. They have had large gaps in their catalog since early 2020 and he says it’s not likely to get better for some time. They have their own bike brands and are having a lot of difficulty obtaining complete bicycles, normally stocking dozens of bikes, now only offering five. I believe they get most of the frames from Taiwan.

One of the far future effects of Coronavid will be the stealth unseen micro-cell damage to multiple organs and organ-systems within the bodies of the “seemingly recovered”. Right now this damage is only not-felt as missing organ-function-reserve, currently not called upon because not needed.

But as people and their organs with this damage age and lose normal function normally with passing time, they will discover they have run out of runway several decades before they would have expected to.

And that, too, is long range damage.

While I’m pleased to see that this issue is being examined in a thoughtful way, I’m with Yves — we are nowhere near the end of this thing, and I suspect we’re closer to the end of the beginning …

No mention of possible economic repercussions of firing all non-vaccinated, especially from Federal Government? I have to imagine there will be quite a loss across the board if they follow through with their silly threat. That can’t be good for long (or short) term growth.

I wonder about this one, too. Even if it only pushes a large bunch of folks into early retirement, that will have effects both positive and negative. A negative would be a lot lower labor participation rate and drag on SS & Medicare funds. A positive would be opportunities for younger folks to move up the ladder.

Article says:

“Reform” is e-con keyword for “making sure that people are being worse off” and structural means “a large bunch of them”. It’s all priced in!

Risks:

Airlines and cruise ship companies have been zombified. Their market valuations are low relative to the high flying tech monopolies and other profitable sectors, but they are still priced too high. Business travel isn’t coming back, there are too many risks and whacking all but the most expensive travel, for C-level types done typically in private jets, is low hanging fruit for bean counters. See recent Dell memo that restricted corporate travel to only customer-facing and requiring VP level approval. Look for moar equity dilution and kick-the-can games with debt maturities. If business travel doesn’t come back by 2023, a major US airline that misplayed the situation and bought the normalcy bias will file for Ch. 11.

Vaccine mandates may make labor shortages worse. Or muddy the waters to the extent that just keeping offices closed for another 6-12 months to let legal issues play out is the only common sense option for corporations.

Permanent damage to the educational system. The effect of going on 2 years of virtual schooling and collapsing public schools is unknown. Kids bounce back faster than adults, but some permanent damage seems likely here. Silver lining – the current crop of 16-19 year olds might have figured out that higher ed is largely a scam and they “just say no” to becoming good little corporate drones.

Occupy your education.

Occupy your future.

Occupy your life.

9 new C19 pharma billionaires, 40 new in-total C19 billionaires? What’s not to like about the C19 economy? What’s the problem? (or, who’s problems are we really talking about here? )_

exactly. let them eat cake

I think that has recently happened in a few locations in the south, in the sense that the wait time was so long the person died in the lobby or while waiting for emergency surgery, and lockdowns did not materialize, but perhaps it hasn’t been sufficiently bad yet

Isolated cases are one thing, and the infection rate has fortunately fallen off.

If people perceive they can’t get care at an ER, that’s another. I felt that way with my mother, that at 93, she’d be put at the back of the queue…even with a probable stroke.

Another metric is across the board postponement of elective surgeries. People with really bad joints are in pain while waiting for replacements. Having to hold off for months is a problem for them.

This pandemic is far from over. Not much in the news about it yet but the Gamma variant is causing problems in South America. CDC has it on their Emerging Infectious Diseases page with a conclusion of “We describe a COVID-19 Gamma variant cluster with a high attack rate even in fully vaccinated persons.”, and “Such a low vaccine efficiency against infection by the Gamma variant was not expected because in vitro studies have shown a similar reduction of neutralization for Beta or Gamma variants…”, and “In conclusion, we describe a VOC Gamma COVID-19 outbreak with a strikingly high attack rate among persons fully vaccinated”. So apparently the virus is mutating into something where the “vaccine” is not effective and it is pretty nasty. What if this mutation gets loose elsewhere? I think its high time that the powers that be realize a central, coordinated effort by our government is going to be needed to keep our economy from going over a cliff. Neo-liberal market based answers just are not going to work. A new paradigm is taking effect I believe and the days of capitalism as a defining economic model is over.