Once touted by its creator as the “Mercedes Benz” of pensions, Chile’s defined contribution scheme is suffering major outflows.

For over 40 years Chile, South America’s most privatised economy, where even the water is in private hands, has been held up as a poster child for neoliberal economics. The Pinochet dictatorship’s early years certainly provided the perfect testing ground for free market reforms conceived in the classrooms of the University of Chicago. The Chicago Boys, a group of 30 Latin American economists who had become acolytes of Milton Friedman as students in the US, took up key policy roles in Pinochet’s government. In next to no time they had unleashed a battery of reforms that made their mentor proud — at least for a short while.

But in the end, as Yves documents in ECONNED (cited here), Chile was not really a successful “free markets” experiment. Key parts of the economy, such as the copper mining industry, remained under firm government control. The Chicago Boys’ policies gave birth to a massive debt-fuelled speculative bubble, with “the funds going mainly to real estate, business acquisitions, and consumer spending rather than productive investment.” The rich made out like bandits, as state assets were sold for huge discounts to connected insiders, while the poor got even poorer. For many of them, as Yves put it, “the Catholic Church’s soup kitchens became a vital stopgap.”

And then the boom turned to bust, leaving Pinochet’s government little choice but to reverse many of the Chicago Boys’ policies:

The bust came in late 1981. Banks, on the verge of collapse thanks to dodgy loans, cut lending. GDP contracted sharply in 1982 and 1983. Manufacturing output fell by 28% and unemployment rose to 20%. The neoliberal regime suddenly resorted to Keynesian backpedaling to quell violent protests. The state seized a majority of the banks and implemented tougher banking laws. Pinochet restored the minimum wage, the rights of unions to bargain, and launched a program to create 500,000 jobs.

One of the Chicago Boys’ most enduring legacies — Chile’s fully privatised pensions system — is now beginning to unravel. Created in 1980, it was the first pensions system in Latin America that depended entirely on compulsory workers’ contributions. The model has since served as a template for similar systems in emerging economies across the world. But its days appear to be numbered, which is causing all sorts of consternation, not only among Chile’s large business owners, managerial class and the administrators of the pension funds (AFPs) but also at banks and funds on Wall Street.

The System’s Losers

Here’s how the system works: all employees within the formal economy must pay at least 10% of their monthly salary to for-profit funds, called AFPs. The government plays no role — or at least is not supposed to — and employers do no have to contribute anything. Employees must also pay the eye-watering commissions charged by the AFPs for managing their money, most of which is invested in large Chilean banks, large Chilean companies and overseas assets. In return, most pensioners — particularly those at the lower end of the income scale — receive a measly pension at the end of their working lives.

Many people in the country, particularly those in the informal economy, cannot make regular enough contributions to end up with sufficient payouts. But the system itself is designed not to pay pensions, says Chilean economist Manuel Riesco. According to a study he conducted in 2013, workers in 2012 paid out more than twice (4.3 trillion pesos) the amount of money they would end up receiving (2.1 trillion pesos). What’s more, the State provided 1.4 trillion pesos in subsidies to the AFPs — equivalent to two thirds of the amount paid out in pensions. In other words, just over one out of every three pesos invested actually got paid back.

The result is widespread penury. In 2020, over half of Chile’s retirees received under $203 a month or less last year — in a country where prices for basic products and services are comparable to those in many European countries.

Now the system itself, once touted by its creator, José Piñera Echenique (brother of the current president), as the “Mercedes Benz” of pensions, appears to be falling apart. In his study Riesco forecast that Chile’s pensions crisis would take a sharp turn for the worse in 2016 when the first generation of workers who had only made payments into the current system would begin retiring. It was a prescient prediction. Despite the Bachelet government’s pension reforms of 2017, which laid the groundwork for some pension precarity, along with with low wages, high living costs and unafforable health care, was among the main grievances that drove over a million people onto the streets of Santiago in October 2019.

The Winners

But where there are losers there must also be winners. They include Chile’s armed forces, police and other state security agencies, which to this day have benefited from a more generous system.

Also, all the money that Chilean workers have paid into the pension system has helped to lay the foundations of a disproportionately large (by Latin American standards) capital market. Its accumulated funds amount to roughly 60% of Chile’s GDP. As even Reuters conceded in 2019, “the money that poured into the AFPs’ coffers helped fuel an economic boom that saw a small elite flourish and gleaming glass and mirror towers come to dominate the skyline of Santiago.”

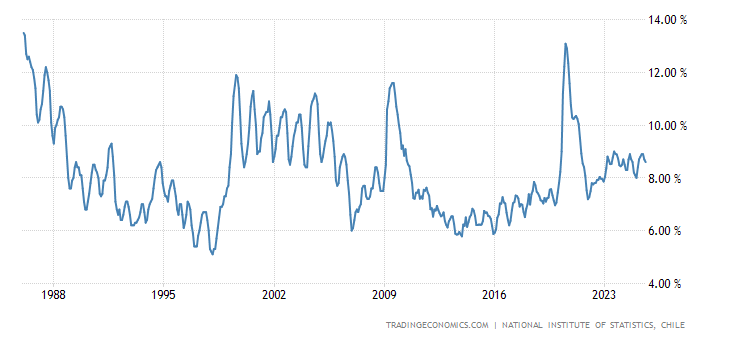

But even that money is dwindling fast as the aftershocks of the virus crisis continue to reverberate. In June last year official unemployment in Chile hit a 33-year high of 13%. Many small businesses were wiped out.

The government mobilised emergency funds for the most vulnerable social groups. But many in the middle-classes were left to fend for themselves. By July 2020 conditions were so grim that Chile’s congress approved a motion allowing citizens to cash in as much as 10% of their pension fund. Chile’s billionaire president, Piñera, was not happy with the plan but he had enough political nous to go along with it.

Over the following ten months another two withdrawals were permitted. Around $50 billion has been redeemed so far, leaving the AFPs with just $180 billion of equities and fixed income assets funds, down from around $230 billion in 2019. It’s a big drop in a short space of time, the equivalent of 17% of Chile’s GDP. The senate is now considering whether to authorise a fourth wave of redemptions, which could drive the total amount withdrawn to over $60 billion.

General Elections Loom

Some opponents warn that the recent redemptions form part of a general strategy to cripple the AFP system. With general elections looming in November, they fear that a new leftist government led by 35-year old Gabriel Boric, currently front-runner in the polls, might follow the example of former Argentinean president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s, who passed a law in 2008 to nationalise Argentina’s private pensions system. That system had only $30 billion of funds in its coffers at the time; Chile’s currently has $180 billion.

Bloomberg describes Chile’s private pensions as a “bedrock of the country’s system”:

“The savings they have generated over the past four decades have given local credit markets and the peso a stability that is the envy of serial defaulters such as Argentina or Ecuador, and prompted countries including Peru and Colombia to adopt similar structures.”

But millions of middle-class Chileans who have been forced to finance the scheme feel they haven’t benefited from the stability it has created. Many of them cannot even afford to retire on the meagre provisions it provides.

Despite a recent improvement in the Chilean economy’s overall performance, the situation is still extremely fragile. In recent days the Chilean peso slid to an 18-month low. If this trend continues it could plumb depths not seen in decades. Inflation, at 5.3%, is at its highest level since 2014. The country’s benchmark equity index, S&P IPSA, is down almost 20% over the last six months. In the past week yields on the government’s ten-year bonds surged to levels not seen since the dark days of 2008.

This is happening for a number of reasons. The withdrawals have forced AFPs to offload bonds into the market to fund redemptions, putting upward pressure on yields. The prospect of more redemptions ahead has further exacerbated this trend. Chile’s lower chamber of Congress has already approved a bill to allow a fourth round of redemptions, but it faces stiffer opposition in the Senate.

In mid-August Chile’s central bank warned that a fourth withdrawal could have “extremely serious effects”, including fuelling higher inflation. Amcham Chile and Chilean financial regulators have voiced particular concern about a clause in the new draft legislation that would permit retirees who have purchased an annuity to obtain an advance of up to 10% on their funds from insurance companies. Chile’s financial regulator has cautioned that the terms of the bill could potentially render insolvent nine insurers that deal in the annuities.

Chile, Latin America’s most privatised economy, an economy that has served as a model for so many others, is at a crossroads. The huge explosion of public rage in 2019 was a tipping point, a “basta, ya!” moment. Now, just six weeks away from new elections, poll suggest that the country is on the verge of electing the leader of a left-wing coalition who has pledged to “overturn the AFPs” and replace them with “a social security system and decent pensions.” Whether he actually wins the election and delivers on that pledge still awaits to be seen.

The good news is that the country has one of the lowest debt to GDP ratios in Latin America, which means the new government should have plenty of scope for public spending to increase. The bad news is that many people in the country are burning through their pensions before they even reach retirement age. To create a fairer, more inclusive pensions system that combines elements of both individual and collective schemes as well as redistributive effects, the AFPs may need to be sacrificed, says former finance minister Rodrigo Valdes. The big question is whether this can be done without the usual attendant turmoil — often the result of capital flight — that tends to accompany big moments of transition in the region.

A small distorted anecdote to a large country with big problems.

I agree that AFP is a garbage system with ridiculous management fees and it is/was woefully inadequate/underfunded for retirees. I am of the belief that most private pensions systems are just elaborate scams to the benefit of coke sniffing capitalists — labour is never going to be competitive in capital markets. If capital markets need investments it should directly come from the sovereign entity (Chile can do this).

However the AFP redemption have also been scams. That money looks to have mostly boosted consumer durable goods spending during a supply crunch. It was a lazy policy decision in response to forced government shutdowns/quarantines and Covid.

An employee/worker on a nearby farm used his first 10 percent for a down payment on a car. He had the usurious note (30+ percent interest) guaranteed by a friend (his credit was already destroyed with a previous run in with loan sharks). Complete disaster in the making. Thankfully, after a couple break downs, the car moved on. However, nothing to show for in the way of quality of life improvements. I have noticed a significant increase in Cars on roads in the last year.

Friends, most of which have money, sunk all their withdrawals in consumption splurges. A minority used the money for home improvements.

You can make an argument that given the predatory/woeful nature of the AFP, you might as well return all the money. Seems like dumb policy with significant disruptions (interest rates, consumer demand, supply crunch) and short sighted to me. It certainly is not an improvement.

Praxis, thanks for the anecdote. I’m sure that there must be quite a few people who, like your friend, are splurging on consumer durables, just as many of the recipients of US stimulus cheques didn’t need the money at all. It is certainly strange to watch so many people spend their pension funds years — perhaps even decades — before they even reach retirement age. I agree that the policy of offering pension withdrawals on such a scale is myopic and potentially very risky. It has already added further fuel to inflation and has sparked a sharp sell off of Chilean assets. If the senate does approve a fourth wave of redemptions I wonder if it will spur people who had no intention of taking out their money to do so out of fear about the sustainability of the system. I know that’s probably what I would do.

Spending as much as possible immediately can be a completely rational decision if you don’t expect to get this money decades from today – due to bankruptcy of the entity managing it, inflation, climate change etc

Russia also adopted the defined contribution approach in the 2000s when many other Western fads were adopted in a cargo-cultish manner. I myself started paying towards my future pension. It took much less than Chilean 40 years for the system to crumble. In 2014 it was announced that the motherland needs money and therefore that year’s defined benefits contributions were channeled to the current pensioners. The same happened in 2015 and along the road there were at least two more reforms, each adding the complexity and changing the terms.

At some point I stopped keeping track and I have zero hope of ever receiving any of that money back.

I really think most pensions are labour scams enacted in the interest of providing jobs for PMC’s. Retiree money should be a livable wage stipend set and paid by the government — how it comes up with money is irrelevant. The government is the most transparent entity that can redistribute economic surplus to retirees. Stick to simple. Stick to transparency. Also, if the system is good, retirees like to vote so it can’t be easily mothballed.

True and in many countries the PMC also benefits disproportionately from the tax-treatment of the contributions to the private pension. Seems a bit strange that the people with the highest wages needs the biggest government incentive to save but so it is. Income earners who earn well above the average salary can’t (or possibly won’t) save without government subsidies. (at least that is how it works in Ireland and in Sweden, might differ in other countries)

Social status spending is a thing, one that happens in all social classes.

Would simple modifications like capping AFP fees have kept the system working?

Or was it never going to be enough to contribute 10% of salaries through a 35-year working life to finance a 20-year retirement? Average OECD contribution rates are much higher.

Bush tried in 2005 to get the Democrats to go along with replacing Social Security with a privatized defined benefit scheme. They, amazingly, balked. It deceived me into believing they actually stood for something. All events since then have disabused me of that notion.

Yes, indeed. Apparently, when Paul Krugman visited Chile in 2009 he was shocked to see how the AFP system worked. He is reported to have said “Thank God we have kept a state-based pensions model in the US,” adding that if the US had taken on a fully privatised scheme like the AFP, it would have produced another big crisis.

‘President Barack Obama advocated historic cuts to social security, Medicare, and Medicaid, in exchange for an increase in federal taxes on upper income, with the goal of reducing the federal deficit’–

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_bargain_(United_States,_2011)

So there would be massive cuts to social security, Medicare, and Medicaid for a promise that there would be (temporary) taxes on upper income – which they would be able to dodge anyway? And with the goal of reducing the federal deficit? Is that how like the budget for a country is just like that of a household and must balance? If not for the Tea Party faction, Obama may have gone down in history as the Catfood President.

The daily tracking polls indicated seniors and near seniors soured on Shrub rapidly. This is when the GOP created the Terry Schaivo circus. It helped his numbers until Iraq bad news couldn’t be ignored, but the GOP moved on. It’s why they didn’t try it with Trump. They know it’s a killer.

Its not a story about the Democrats. There were enough Democrats who are craven to have stood with Shrub. As Rev Kev notes, Obama showed Team Blue’s views. The Republicans panicked. They knew full well that they were and are an unpopular party and can’t expect Team Clinton to mismanage their way to a GOP victory every time.

As I recall, the proposal was that you could send up to 1/6 of your allowable contribution to a private fund to be gambled with.

and low and behold, look at who was in complete thrall of the economic nonsense. straight from the horses mouth,

http://www.josepinera.org/articles/articles_clinton_chilean_model.htm

and of course empty suit was at it also.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2016/09/30/the-democratic-plot-to-privatize-social-security/

The reason the DLC Clintocrats balked at supporting Bush’s privatisation plan for Social Security is that Bush was Republican. The DLC Clintocratic Party wants a Clintocratic President to be the great historical reformer who pulls a “Nixon goes to China” on Social Security. The Democrats were strictly and only motivated by keeping the ” Nixon goes to China” chair empty until they could fill it with a Democrat.

What is my support for this? President Clinton was conspiring with Gingrich to privatise Social Security till he was derailed by the Monica Lewinski affair. Obama appointed the notorious Clintonite Erskine Bowles to co-serve along with Social Security hater Senator Simpson on the Obama Catfood Commission to privatise Social Security.

Thanks for this post. Friedman’s theories rested on the unspoken assumption that men in the private sector all had fine character and would never abuse the system to enrich themselves. There was also the added fig leaf of the mythical “market” which would, we were told, root out bad actors and bad practices. “The market” idea displaced govt regulations and enforcement with a magic trick. It was all a sham. It opened the door to unchecked private looting of the public.

In the case of Chile, the “experts” also brought in extreme authoritarianism to silence public objections to the plan.

Milton Friedman has blood on his hands. (Full disclosure, I know his kid, but we discuss medieval cooking, garb, and customs, particularly as it pertains to the Middle East, not politics or economics.)

The Shock Doctrine at it’s finest.

Now that torture is acceptable to the U.S. when will it be applied here?

Chicago PD

“It can’t happen here” – Frank Zappa

Didn’t police torture a lot of roundup-victims during the OWS encampment shutdowns when they thought they were out of camera-shot? How too-tight do zip-tie cuffs need to be before it is torture? I read about police at the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle playing the game of putting a pencil between each of the fingers of a detainee’s hand and then laterally crushing that detainee’s hand, for fun. Etc.

Mass torture would probably be achieved with ultra-high-decibel sound machines, LRAD eardrum rupturisers, microwave-based Ratheon Oven Rays, etc. People at demonstrations should watch out for those things. Maybe nauseagenic infrasound generators. Maybe the Havana Syndrome remote brain-damage generators which every good radical assures us “do not even exist”, will also be discovered in due course to ” not even exist” at American demonstrations, where people will also come away with all kinds of “purely hysteria based” brain damage.

I will be very picky-choosy about what demonstrations I attend, and will watch closely for the first sign of “mystery men” with “mystery technologies” on the back of military trucks.

How can this discussion not mention the recently elected Chilean Constitutional convention, where the reactionary Friedmanite polity got less than the 1/3 required to veto changes?

It is clear that the corrupt and wasteful pension system was a major driver in those results.